I need four strong questions based on this reading

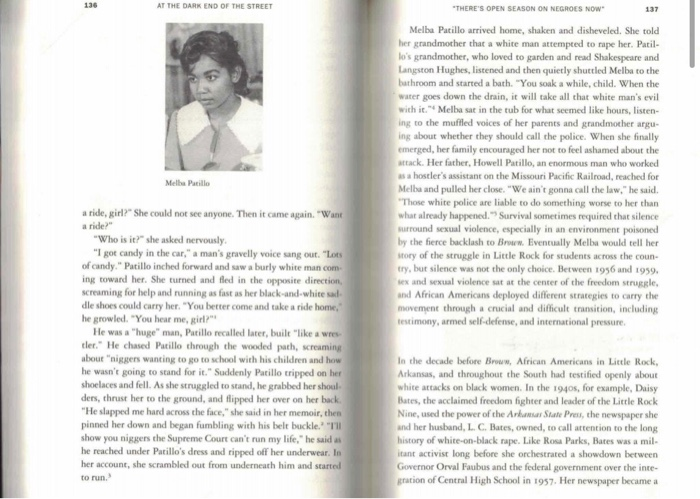

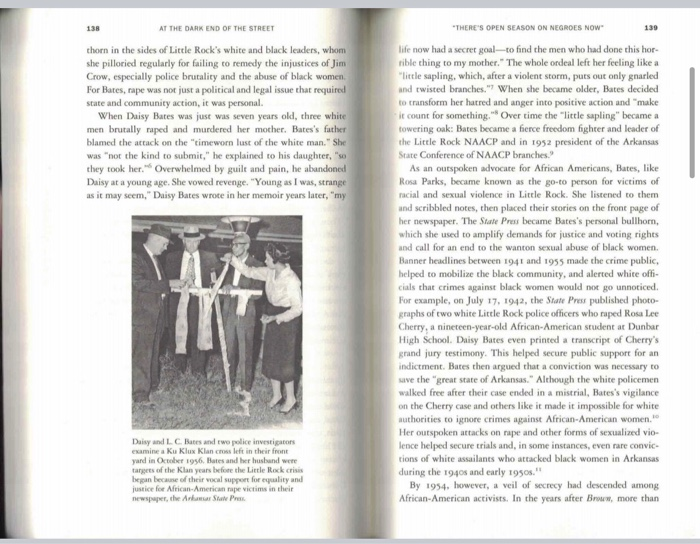

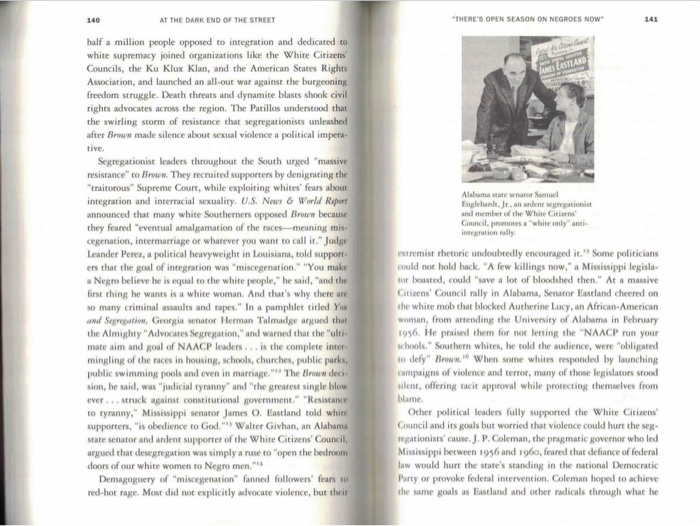

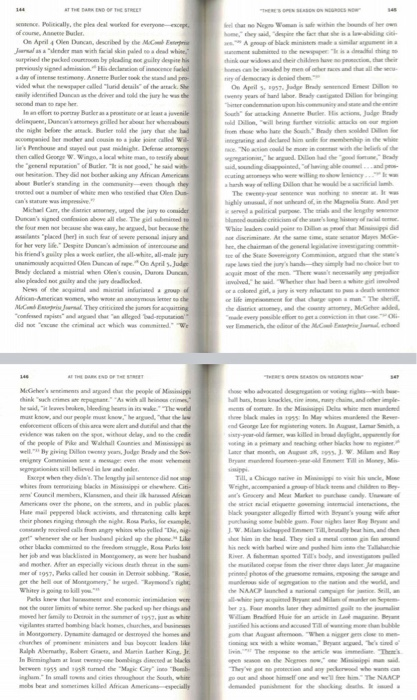

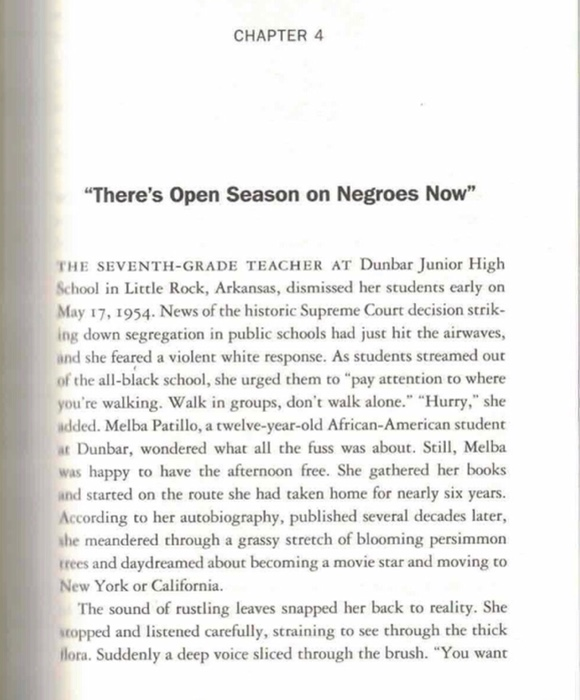

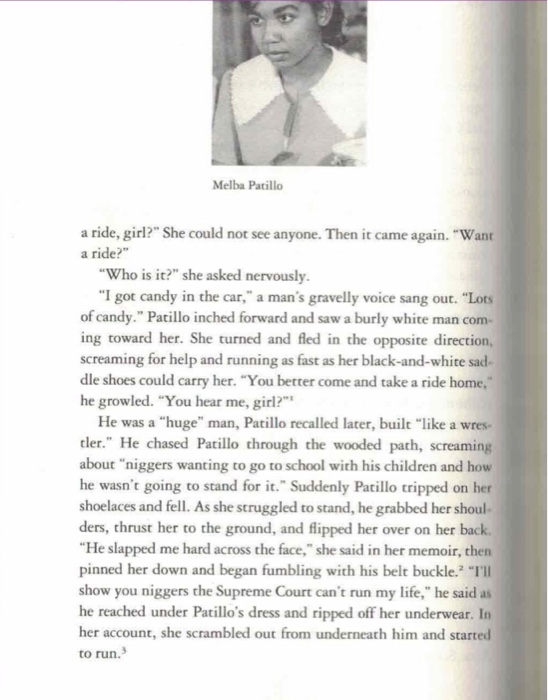

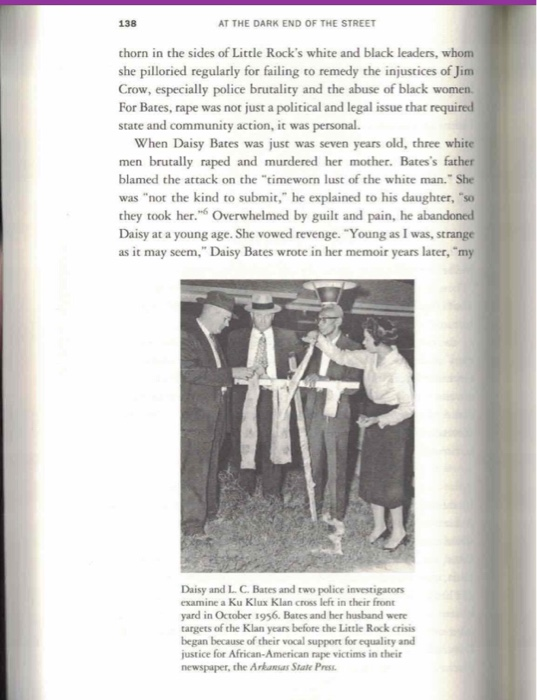

134 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET Martin Luther King, Jr., later called the "thingification" of white supremacy. By walking hundreds of miles to protest humili ation and testifying publicly about physical and sexual abuse, African Americans--mostly women--reclaimed their bodies and demanded the right to be treated with dignity and respect CHAPTER 4 "There's Open Season on Negroes Now" The legal and moral victory over white supremacy in Montgom- ery gave African Americans around the country a sense of hope for the future, an inspirational and powerful figurehead in Mar tin Luther King, Jr., and an organizing model-nonviolent direct action, which they hoped to use throughout the South to disman tle Jim Crow. Segregationists intent on thwarting black advances launched their own war to retain their position of power in the South. A swirling storm of white resistance had been gathering since the 1954 Broww * Board of Education decision. As African Americans in Montgomery returned to the buses and some South- ern schools took baby steps toward compliance with the Brown decision, the "massive resistance" movement thundered through the South Drawing on whites' deepest fears about integration and interracial sexuality, Citizens' Council members and other die-hard segregationists used economic intimidation, sexual ixed violence, and terror to derail desegregation and destroy the developing black freedom movement. Between the Montgomery bus boycott and the student sit-in movement in 1960, African Americans hoping to re-create the Montgomery experience faced the forces of Jim Crow, sparking some of the fiercest battles for manhood and womanhood of the modern civil rights movement. THE SEVENTH-GRADE TEACHER AT Dunbar Junior High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, dismissed her students early on May 17, 1954. News of the historic Supreme Court decision strik- ing down segregation in public schools had just hit the airwaves, and she feared a violent white response. As students streamed out of the all-black school, she urged them to "pay attention to where you're walking, Walk in groups, don't walk alone." "Hurry," she added. Melba Patillo, a twelve-year-old African-American student Dunbar, wondered what all the fuss was about. Still, Melba was happy to have the afternoon free. She gathered her books and started on the route she had taken home for nearly six years. According to her autobiography, published several decades later, the meandered through a grassy stretch of blooming persimmon trees and daydreamed about becoming a movie star and moving to New York or California The sound of rustling leaves snapped her back to reality. She stopped and listened carefully, straining to see through the thick flora. Suddenly a deep voice sliced through the brush. "You want 136 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 137 Melba Patillo Melba Parillo arrived home, shaken and disheveled. She told her grandmother that a white man attempted to rape her. Patil- lo's grandmother, who loved to garden and read Shakespeare and Langston Hughes, listened and then quietly shuttled Melba to the bathroom and started a bath. "You sok a while, child. When the water goes down the drain, it will take all that white man's evil with it." Melba sat in the tub for what seemed like hours, listen- ing to the muffled voices of her parents and grandmother argu- ing about whether they should call the police. When she finally emerged, her family encouraged her not to feel ashamed about the attack. Her father, Howell Patillo, an enormous man who worked us a hostler's assistant on the Missouri Pacific Railroad, reached for Melba and pulled her close. "We ain't gonna call the law," he said. "Those white police are liable to do something worse to her than what already happened." Survival sometimes required that silence surround sexual violence, especially in an environment poisoned by the fierce backlash to Brown. Eventually Melbu would tell her story of the struggle in Little Rock for students across the coun try, but silence was not the only choice. Between 1996 and 1959. sex and sexual violence at at the center of the freedom struggle. and African Americans deployed different strategies to carry the movement through a crucial and difficult transition, including testimony, armed self-defense, and international pressure. a ride, girl?" She could not see anyone. Then it came again. Want a ride?" "Who is it?" she asked nervously "I got candy in the car," a man's gruvelly voice sang out. "Lots of candy. "Patillo inched forward and saw a burly white man com ing toward her. She turned and fled in the opposite direction, screaming for help and running as fast as her black-and-white sal dle shoes could carry her. "You better come and take a ride home, he growled. "You hear me, girl?" He was a huge man, Patillo recalled later, built "like a wre tler." He chased Patillo through the wooded path, screaming about "niggers wanting to go to school with his children and how he wasn't going to stand for it." Suddenly Patillo tripped on her shoelaces and fell. As she struggled to stand, he grabbed her shoul. ders, thrust her to the ground, and flipped her over on her back. "He slapped me hard across the face," she said in her memoir, then pinned her down and began fumbling with his belt buckle." "TH show you niggers the Supreme Court can't run my life," he said as he reached under Patillo's dress and ripped off her underwear. In her account, she scrambled out from underneath him and started to run. In the decide before Broww, African Americans in Little Rock, Arkansas, and throughout the South had testified openly about white attacks on black women. In the 1940s, for example, Daisy Bates, the acclaimed freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock Nine, used the power of the Arawa State Press, the newspaper she and her husband, LC. Bates, owned, to call attention to the long history of white-on-black rape. Like Rosa Parks, Bates was a mil- tant activist long before she orchestrated a showdown between Governor Orval Faubus and the federal government over the inte gration of Central High School in 1957. Her newspaper became a 139 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET thorn in the sides of Little Rock's white and black leaders, whom she pilloried regularly for failing to remedy the injustices of Jim Crow, especially police brutality and the abuse of black women. For Bates, rape was not just a political and legal issue that required state and community action, it was personal. When Daisy Bates was just was seven years old, three white men brutally raped and murdered her mother. Bates's father blamed the attack on the "timeworn lust of the white man." She was "not the kind to submit," he explained to his daughter, "so they took her. Overwhelmed by guilt and pain, he abandoned Daisy at a young age. She vowed revenge. "Young as I was, strange as it may seem," Daisy Bates wrote in her memoir years later, "my "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW life now had a secret goal--to find the men who had done this hor- rible thing to my mother." The whole ordeal left her feeling like a "little sapling, which, after a violent storm, puts out only gnarled and twisted branches." When she became older, Bates decided to transform her hatred and anger into positive action and make it count for something."* Over time the little sapling" became a towering oak: Bates became a fierce freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock NAACP and in 1952 president of the Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches. As an outspoken advocate for African Americans, Bates, like Rosa Parks, became known as the go-to person for victims of racial and sexual violence in Little Rock. She listened to them and scribbled notes, then placed their stories on the front page of her newspaper. The State Press became Bates's personal bullhorn, which she used to amplify demands for justice and voting rights and call for an end to the wanton sexual abuse of black women, Banner headlines between 1941 and 1955 made the crime public, helped to mobilize the black community, and alerted white offi- cials that crimes against black women would not go unnoticed For example, on July 17, 1942, the State Press published photo- graphs of two white Little Rock police officers who raped Rosa Lee Cherry, a nineteen-year-old African-American student at Dunbar High School. Daisy Bates even printed a transcript of Cherry's grand jury testimony. This helped secure public support for an indictment. Bates then argued that a conviction was necessary to save the great state of Arkansas." Although the white policemen walked free after their case ended in a mistrial, Bates's vigilance on the Cherry case and others like it made it impossible for white authorities to ignore crimes against African-American women. Her outspoken attacks on rape and other forms of sexualized vio- lence helped secure trials and, in some instances, even rare convic tions of white assailants who attacked black women in Arkansas during the 1940s and early 1950s." By 1954, however, a veil of secrecy had descended among African-American activists. In the years after Brouw, more than Daisy and LC. Bates and two police investigators examine a Ku Klux Klan crow left in their front yard in October 1956. Bates and her husband were targets of the Klan years before the Little Rock crisis began because of their vocal support for equality and justice for African-American rape victims in their newspaper, the Alta Press 140 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 141 EASTLAND half a million people opposed to integration and dedicated to white supremacy joined organizations like the White Citizens' Councils, the Ku Klux Klan, and the American States Rights Association, and launched an all-out war against the burgeoning freedom struggle. Death threats and dynamite blasts shook civil rights advocates across the region. The Patillos understood that the swirling storm of resistance that segregationists unleashed after Broww made silence about sexual violence a political impera tive Segregationist leaders throughout the South urged "massive resistance to Broww. They recruited supporters by denigrating the "traitorous" Supreme Court, while exploiting whites' fears about integration and interracial sexuality. U.S. News & World Report announced that many white Southerners opposed Brow because they feared "eventual amalgamation of the races-meaning mis- cegenation, intermarriage or whatever you want to call it." Judge Leander Perez, a political heavyweight in Louisiana, told support ers that the goal of integration was "miscegenation." "You make a Negro believe he is equal to the white people," he said, "and the first thing he wants is a white woman. And that's why there are so many criminal assaults and rapes." In a pamphlet titled you und Segregation, Georgia senator Herman Talmadge argued that the Almighty "Advocates Segregation," and warned that the ulti mate aim and goal of NAACP leaders... is the complete inter mingling of the nices in housing, schools, churches, public parks, public swimming pools and even in marriage." The Brow deci sion, he said, was "judicial tyranny" and "the greatest single blow ever... struck against constitutional government." "Resistance to tyranny," Mississippi senator James O. Bastland told white supporters, "is obedience to God. Walter Givhan, an Alabama state senator and ardent supporter of the White Citizens' Council, argued that desegregation was simply a ruse to open the bedroom doors of our white women to Negro men." Demagoguery of "miscegenation" fanned followers' fears to red-hot rage. Most did not explicitly advocate violence, but their Alabama state water Samuel Englehunde, Jr, an ardent segregationist and member of the White Citizens Council, promotes a white only anti integrationally extremist rhetoric undoubtedly encouraged it. Some politicians could not hold back. "A few killings now," a Mississippi legisla tor boasted, could save a lot of bloodshed then." At a massive Citizens' Council rally in Alabama, Senator Eastland cheered on the white mob that blocked Autherine Lucy, an African-American woman, from attending the University of Alabama in February 1956. He praised them for not letting the "NAACP run your schools." Southern whites, he told the audience, were "obligated to defy" Brow. When some whites responded by launching campaigns of violence and terror, many of those legislators stood silent, offering tacit approval while protecting themselves from blame Other political leaders fully supported the White Citizens' Council and its goals but worried that violence could hurt the seg regationists' cause. J. P. Coleman, the pragmatic governor who led Mississippi between 1956 and 1960, feared that defiance of federal law would hurt the state's standing in the national Democratic Party or provoke federal intervention. Coleman hoped to achieve the same goals as Eastland and other radicals through what he 142 143 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET called "practical segregation." He pushed for the creation of a state agency that would mirror the FBI's investigative prowess and function as a public relations bureau. His goal was to "keep racial conflict out of the press while quietly and effectively man aging the state's fight against integration." Coleman tested the effectiveness of the newly formed State Sovereignty Commission in May 1956, when four white men from Tylertown, a small vil- lage in the Piney section of Mississippi, kidnapped a young black woman on the eve of her wedding and gang-raped her. It was just before dawn on May 13, 1956-Mother's Day when Ernest Dillon, a twenty-nine-year-old siding salesman; his brother Ollie, a middle-aged construction worker, and Olen and Durora Duncan, twenty-one-year-old cousins, went looking for "some colored women." Wielding a shotgun, Ernest Dillon approached Sennis Butler, a thirty-year-old black sharecropper who was outside preparing for the day's work. Dillon ordered him to take him and his friends to a home with black women inside. Annette Butler, a sixteen-year-old high school student, was in bed with her mother when she heard someone pounding on the front door of their two-bedroom home. Ernest Dillon introduced himself as a policeman. "You're under arrest," he said to the girl, for "sacking up with your boyfriend." When her mother objected, Dillon raised the shotgun, grabbed the teenager, and pulled her outside. He kept the shotgun trained on the girl's mother as his brother pushed her into the backseat of the car. Olen Duncan revved the engine and drove away, leaving Butler's mother alone in the front yard." The four white men drove Butler deep into the Bogue Chitto swamp, where they took turns raping her. Olen Duncan threar- ened to cut her neck off" if she resisted. "I followed his instruc- tions," she testified at the trial. When they finished, the four white men piled into the car and left Annette stranded in the woods. Wandering through the swamp half naked, she stumbled upon a group of black fishermen and ran to them for help. They led "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW her out of the woods and delivered her to the police. Sheriff A.E. (Bill) Andrews took her complaint and then drove her home to get dressed. Later that day Sheriff Andrews brought Olen Duncan in for questioning, and he willingly signed a statement testifying that he had had "intimate relations" with Annette Butler. "It was done with every safeguard for the right of the defendant," Sheriff Andrews said, "after (Duncan] had been repeatedly advised that anything he might say could be used against him."** A few days later District Attorney Michael Carr charged all four men with "forcible ravishment and kidnap" and sent them to the Magnolia jail to await trial." Judge Tom Brady, a fierce white supremacist and one of the fathers of the White Citizens' Councils, presided over four sep arate trials in Pike County Circuit Court four months after the attack. The assailants must have wondered what kind of pun ishment Brady would impose since his public pronouncements against interracial mixing were already legendary. Time magazine called Brady the prophet" of segregation and his manifesto, Black Monday, the "Bible of the White Citizens' Council movement." When confronted with real interracial mixing and actual map ists, not the fictional black rapists he saw lurking behind every school-desegregation case, Brady buckled under the weight of his own racial prejudices. He appointed the "finest lawyers in Missis- sippi" to defend the four white assailants. Ernest Dillon may not have understood Brady's gesture, since he pleaded guilty on March 26, 1957, to the lesser charge of "assault with intent to rape." It was a risky plea that left his co-conspirators vulnerable. On the other hand, the plea bargain released him from trial and from the threat of the death penalty or life imprisonmentthe state's only punishments for rape. It also freed the jurors from having to declare a white man guilty of raping a black woman and defused any complaints of unequal justice or outside criticism of the state. It is likely that Dillon believed he would receive a minor sentence or even a suspended ute or death for rope ??? 16 145 feel that ne Nene Wie within the bounds of her own A group of Hacker On April 9 Buy wynhand her. By die for being Secondi comunity and mandhari She forwacking Austin, Jade AT THE END OF THE STREET willy, the pledeal wake for everyone of course On April 4 Olen Duncan, described by the ME Juru sender man with facial skin palied to deal white, surprised the packed Courtroom by pleading nee guilty despite his previously signed in His declaration of innocence fueled day of mense testimony Annette Butler tek the stand und pro easily identified as the driver and told the jury lewe man her lead to pay Bukas spela juvenile delinquent, c'esgrilled her about her whesabots the night before the wack Butler mother that she had accompanied her mother and into a jake jene called a lie's house and you might Defense then called Gew. Will white man, to estily about the tal reputation of Butler," segoed," he said with out hesitation. They did the king wy Aincan America retumber of white men who wed thu Olen Du Can's sure was impressive." Michael Carr, the duty, why to commider Duncan'da ve all the gibt the four ment became she was cay, Bergued, but because the is placed in such far of we wind for her very Dee Dumond his friend's guilty ples weekerlier, the all-white, all-male jury unanimously quite Ole Dance On April Jude Beady declared when 's cousin, Duro Duncan also pleaded guilheydew News of the wall wil infuriated group of African-America, who were the Mel They criticized the informitting companhellum did we co the criminal which was comme widowingine.comland hash way of light be wearificium Nighly do in the Map See Andy Whiseade.com Dichida mot discriminate the Meyes MEG here, the chairman of the legislatie meting commit of the SS Comme ved," he wider wild a cool, jury is way life imprime for the charge pou The sheriff McGehend and the theople of Missippi chikach crimes with all his crimes heid, eeben, Weedingles in its wake." The weed markow, and our people where there encefice of this arealent and dutiful and that the evidence was taken with dead to the credit of the people of Pen Well Cid Mini well. By giving my youn, July Brady and the enigny Came the weet we will believed in and onder Eept when they didn't. The lengthy jail cedido white from being Wacke in Mippie chewhere. Giti Council members, Klam, and the Afrin Action over the phone on them, and in public places Hune mail per aktiviti alle kope their phonesringing through the nigh. Bo Pales, for cumple comeceived call from any who who yelledieng- when she help the other black cocher, Rosa Puso her job and was blacklisted in Montgomery, wer husband and mother. Ahily with that in the sum. mer of 1957. Purles called her sin in Detroit sobbing." get the hell out of Money, hey " Rodrig those who locate degree or wing righe-withese wil hus, we knuckles, time, my chain, and the imple sofore. I the Missippi Dela white men under che Mack malesia 1955: In Maywhites mund the Re and George Lee for giring women. In August, Lana Smith, sixty-year-old fammer, was killed in bed delighed for Laner hur math.J. W. Miland med fill in Money, Mi Till, Chicago native in Mihinde Me Wright, companindrop of children to be 's Grocery and Me Marker pune candy black yangter allegedly lined with Beyan's young wie se purchasing some blegum Touriger Boy By J. W. Milam kidipped immen Til brutally beat him, and then his neck with bar wire the chie River Afisherman med Tills body and sold the mutiled.com the tive dhe days to me prie photos of the meaning the end the NAP launched in camp for Still, Parks knew theme and economic intimidation were the limits of where Sleeplering her 2 For mother they made them William Bradlied Haie for an article in manier om the Augas femen. "Where to me timing with a white w Budhi wigilantes stumed bombing Wack homes, churches, and be is Montgomery Dynamite damaged or destroyed the homes and churches of promise and bu ce van Ralph Abemuty, Robert Grand Martin Luther King Jr. In Birmingham at www.cne bombings directed Wade between 1955 and 1958 tumed the Magic Geyim"Bob inghem in small towns and cities that the South, white mebebeat indtil African Americnspecially They've and pekerwed who wants can poster The NAACP demanded punishment for the shacking des CHAPTER 4 "There's Open Season on Negroes Now" THE SEVENTH-GRADE TEACHER AT Dunbar Junior High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, dismissed her students early on May 17, 1954. News of the historic Supreme Court decision strik- ing down segregation in public schools had just hit the airwaves, and she feared a violent white response. As students streamed out of the all-black school, she urged them to pay attention to where you're walking. Walk in groups, don't walk alone." "Hurry," she added. Melba Patillo, a twelve-year-old African-American student at Dunbar, wondered what all the fuss was about. Still, Melba was happy to have the afternoon free. She gathered her books and started on the route she had taken home for nearly six years. According to her autobiography, published several decades later, the meandered through a grassy stretch of blooming persimmon trees and daydreamed about becoming a movie star and moving to New York or California. The sound of rustling leaves snapped her back to reality. She scopped and listened carefully, straining to see through the thick Hora. Suddenly a deep voice sliced through the brush. "You want Melba Patillo a ride, girl?" She could not see anyone. Then it came again. "Want a ride?" "Who is it?" she asked nervously. "I got candy in the car," a man's gravelly voice sang out. "Lots of candy." Patillo inched forward and saw a burly white man com ing toward her. She turned and fled in the opposite direction, screaming for help and running as fast as her black-and-white sad- dle shoes could carry her. "You better come and take a ride home," he growled. "You hear me, girl?"* He was a "huge" man, Patillo recalled later, built "like a wres tler." He chased Patillo through the wooded path, screaming about "niggers wanting to go to school with his children and how he wasn't going to stand for it." Suddenly Patillo tripped on her shoelaces and fell. As she struggled to stand, he grabbed her shoul- ders, thrust her to the ground, and flipped her over on her back. "He slapped me hard across the face," she said in her memoir, then pinned her down and began fumbling with his belt buckle. "TII show you niggers the Supreme Court can't run my life," he said as he reached under Patillo's dress and ripped off her underwear. In her account, she scrambled out from underneath him and started to run. *THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 137 Melba Patillo arrived home, shaken and disheveled. She told her grandmother that a white man attempted to rape her. Patil lo's grandmother, who loved to garden and read Shakespeare and Langston Hughes, listened and then quietly shuttled Melba to the bathroom and started a bath. "You soak a while, child. When the water goes down the drain, it will take all that white man's evil with it." Melba sat in the tub for what seemed like hours, listen- ing to the muffled voices of her parents and grandmother argu- ing about whether they should call the police. When she finally emerged, her family encouraged her not to feel ashamed about the attack. Her father, Howell Patillo, an enormous man who worked as a hostler's assistant on the Missouri Pacific Railroad, reached for Melba and pulled her close. "We ain't gonna call the law," he said. "Those white police are liable to do something worse to her than what already happened." Survival sometimes required that silence surround sexual violence, especially in an environment poisoned by the fierce backlash to Brown. Eventually Melba would tell her story of the struggle in Little Rock for students across the coun- try, but silence was not the only choice. Between 1956 and 1959, sex and sexual violence sat at the center of the freedom struggle, and African Americans deployed different strategies to carry the movement through a crucial and difficult transition, including testimony, armed self-defense, and international pressure. In the decade before Brown, African Americans in Little Rock, Arkansas, and throughout the South had testified openly about white attacks on black women. In the 1940s, for example, Daisy Bates, the acclaimed freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock Nine, used the power of the Arkansas State Press, the newspaper she and her husband, L. C. Bates, owned, to call attention to the long history of white-on-black rape. Like Rosa Parks, Bates was a mil- itant activist long before she orchestrated a showdown between Governor Orval Faubus and the federal government over the inte- gration of Central High School in 1957. Her newspaper became a 138 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET thorn in the sides of Little Rock's white and black leaders, whom she pilloried regularly for failing to remedy the injustices of Jim Crow, especially police brutality and the abuse of black women. For Bates, rape was not just a political and legal issue that required state and community action, it was personal. When Daisy Bates was just was seven years old, three white men brutally raped and murdered her mother. Bates's father blamed the attack on the "timeworn lust of the white man." She was "not the kind to submit," he explained to his daughter, "so they took her. Overwhelmed by guilt and pain, he abandoned Daisy at a young age. She vowed revenge. "Young as I was, strange as it may seem," Daisy Bates wrote in her memoir years later, my Daisy and L. C. Bates and two police investigators examine a Ku Klux Klan cross left in their front yard in October 1956. Bates and her husband were targets of the Klan years before the Little Rock crisis began because of their vocal support for equality and justice for African-American rape victims in their newspaper, the Arkansas State Press "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 139 life now had a secret goal to find the men who had done this hor- rible thing to my mother." The whole ordeal left her feeling like a "little sapling, which, after a violent storm, puts out only gnarled and twisted branches." When she became older, Bates decided to transform her hatred and anger into positive action and make it count for something." Over time the "little sapling" became a towering oak: Bates became a fierce freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock NAACP and in 1952 president of the Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches. As an outspoken advocate for African Americans, Bates, like Rosa Parks, became known as the go-to person for victims of racial and sexual violence in Little Rock. She listened to them und scribbled notes, then placed their stories on the front page of her newspaper. The State Press became Bates's personal bullhorn, which she used to amplify demands for justice and voting rights and call for an end to the wanton sexual abuse of black women. Banner headlines between 1941 and 1955 made the crime public, helped to mobilize the black community, and alerted white offi- cials that crimes against black women would not go unnoticed. For example, on July 17, 1942, the State Press published photo- graphs of two white Little Rock police officers who raped Rosa Lee Cherry, a nineteen-year-old African-American student at Dunbar High School. Daisy Bates even printed a transcript of Cherry's grand jury testimony. This helped secure public support for an indictment. Bates then argued that a conviction was necessary to save the "great state of Arkansas." Although the white policemen walked free after their case ended in a mistrial, Bates's vigilance on the Cherry case and others like it made it impossible for white authorities to ignore crimes against African-American women. Her outspoken attacks on rape and other forms of sexualized vio- lence helped secure trials and, in some instances, even rare convic- tions of white assailants who attacked black women in Arkansas during the 1940s and early 1950s." By 1954, however, a veil of secrecy had descended among African-American activists. In the years after Brown, more than 10 140 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET half a million people opposed to integration and dedicated to white supremacy joined organizations like the White Citizens' Councils, the Ku Klux Klan, and the American States Rights Association, and launched an all-out war against the burgeoning freedom struggle. Death threats and dynamite blasts shook civil rights advocates across the region. The Patillos understood that the swirling storm of resistance that segregationists unleashed after Brown made silence about sexual violence a political impera- tive. Segregationist leaders throughout the South urged "massive resistance to Brown. They recruited supporters by denigrating the "traitorous" Supreme Court, while exploiting whites' fears about integration and interracial sexuality. U.S. News & World Report announced that many white Southerners opposed Brown because they feared "eventual amalgamation of the races-meaning mis- cegenation, intermarriage or whatever you want to call it." Judge Leander Perez, a political heavyweight in Louisiana, told support- ers that the goal of integration was "miscegenation." "You make a Negro believe he is equal to the white people," he said, "and the first thing he wants is a white woman. And that's why there are so many criminal assaults and rapes." In a pamphlet titled You and Segregation, Georgia senator Herman Talmadge argued that the Almighty "Advocates Segregation," and warned that the "ulti mate aim and goal of NAACP leaders... is the complete inter- mingling of the races in housing, schools, churches, public parks, public swimming pools and even in marriage." The Brouw deci sion, he said, was "judicial tyranny" and "the greatest single blow ever... struck against constitutional government." "Resistance to tyranny," Mississippi senator James O. Eastland told white supporters, "is obedience to God." Walter Givhan, an Alabama state senator and ardent supporter of the White Citizens' Council argued that desegregation was simply a ruse to open the bedroom doors of our white women to Negro men." Demagoguery of "miscegenation" fanned followers' fears to red-hot rage. Most did not explicitly advocate violence, but their THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW" 141 LANES EASTLAND Alabama state senator Samuel Englehardt, Jr., an ardent segregationist and member of the White Citizens' Council, promotes a "white only" anti- integration rally. extremist rhetoric undoubtedly encouraged it." Some politicians could not hold back. "A few killings now," a Mississippi legisla- tor boasted, could "save a lot of bloodshed then." At a massive Citizens' Council rally in Alabama, Senator Eastland cheered on the white mob that blocked Autherine Lucy, an African-American woman, from attending the University of Alabama in February 1956. He praised them for not letting the "NAACP run your schools." Southern whites, he told the audience, were "obligated to defy" Brown. When some whites responded by launching campaigns of violence and terror, many of those legislators stood silent, offering tacit approval while protecting themselves from blame. Other political leaders fully supported the White Citizens Council and its goals but worried that violence could hurt the seg- regationists' cause. J. P. Coleman, the pragmatic governor who led Mississippi between 1956 and 1960, feared that defiance of federal law would hurt the state's standing in the national Democratic Party or provoke federal intervention. Coleman hoped to achieve the same goals as Eastland and other radicals through what he 142 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET called "practical segregation."'? He pushed for the creation of a state agency that would mirror the FBI's investigative prowess and function as a public relations bureau. His goal was to keep racial conflict out of the press while quietly and effectively man- aging the state's fight against integration."Coleman tested the effectiveness of the newly formed State Sovereignty Commission in May 1956, when four white men from Tylertown, a small vil- lage in the Piney section of Mississippi, kidnapped a young black woman on the eve of her wedding and gang-raped her. It was just before dawn on May 13, 1956Mother's Day- when Ernest Dillon, a twenty-nine-year-old siding salesman; his brother Ollie, a middle-aged construction worker, and Olen and Durora Duncan, twenty-one-year-old cousins, went looking for "some colored women." Wielding a shotgun, Ernest Dillon approached Stennis Butler, a thirty-year-old black sharecropper who was outside preparing for the day's work. Dillon ordered him to take him and his friends to a home with black women inside. Annette Butler, a sixteen-year-old high school student, was in bed with her mother when she heard someone pounding on the front door of their two-bedroom home. Ernest Dillon introduced himself as a policeman. "You're under arrest," he said to the girl, for "sacking up with your boyfriend." When her mother objected, Dillon raised the shotgun, grabbed the teenager, and pulled her outside. He kept the shotgun trained on the girl's mother as his brother pushed her into the backseat of the car. Olen Duncan revved the engine and drove away, leaving Butler's mother alone in the front yard." The four white men drove Butler deep into the Bogue Chitto swamp, where they took turns raping her. Olen Duncan threat- ened to "cut her neck off" if she resisted. "I followed his instruc- tions," she testified at the trial. When they finished, the four white men piled into the car and left Annette stranded in the woods. Wandering through the swamp half naked, she stumbled upon a group of black fishermen and ran to them for help. They led 143 THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW her out of the woods and delivered her to the police. Sheriff A. E. (Bill) Andrews took her complaint and then drove her home to get dressed. Later that day Sheriff Andrews brought Olen Duncan in for questioning, and he willingly signed a statement testifying that he had had "intimate relations" with Annette Butler. "It was done with every safeguard for the right of the defendant," Sheriff Andrews said, "after (Duncan] had been repeatedly advised that anything he might say could be used against him."21 A few days later District Attorney Michael Carr charged all four men with "forcible ravishment and kidnap" and sent them to the Magnolia jail to await trial. Judge Tom Brady, a fierce white supremacist and one of the fathers of the White Citizens' Councils, presided over four sep- arate trials in Pike County Circuit Court four months after the attack. The assailants must have wondered what kind of pun- ishment Brady would impose since his public pronouncements against interracial mixing were already legendary. Time magazine called Brady the prophet" of segregation and his manifesto, Black Monday, the "Bible of the White Citizens' Council movement."23 When confronted with real interracial mixing and actual rap- ists, not the fictional black rapists he saw lurking behind every school-desegregation case, Brady buckled under the weight of his own racial prejudices. He appointed the "finest lawyers in Missis- sippi" to defend the four white assailants. 4 Ernest Dillon may not have understood Brady's gesture, since he pleaded guilty on March 26, 1957, to the lesser charge of "assault with intent to rape." It was a risky plea that left his Co-conspirators vulnerable. On the other hand, the plea bargain released him from trial and from the threat of the death penalty or life imprisonmentthe state's only punishments for rape." It also freed the jurors from having to declare a white man guilty of raping a black woman and defused any complaints of unequal justice or outside criticism of the state. It is likely that Dillon believed he would receive a minor sentence or even a suspended life or death for rope ??? 134 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET Martin Luther King, Jr., later called the "thingification" of white supremacy. By walking hundreds of miles to protest humili ation and testifying publicly about physical and sexual abuse, African Americans--mostly women--reclaimed their bodies and demanded the right to be treated with dignity and respect CHAPTER 4 "There's Open Season on Negroes Now" The legal and moral victory over white supremacy in Montgom- ery gave African Americans around the country a sense of hope for the future, an inspirational and powerful figurehead in Mar tin Luther King, Jr., and an organizing model-nonviolent direct action, which they hoped to use throughout the South to disman tle Jim Crow. Segregationists intent on thwarting black advances launched their own war to retain their position of power in the South. A swirling storm of white resistance had been gathering since the 1954 Broww * Board of Education decision. As African Americans in Montgomery returned to the buses and some South- ern schools took baby steps toward compliance with the Brown decision, the "massive resistance" movement thundered through the South Drawing on whites' deepest fears about integration and interracial sexuality, Citizens' Council members and other die-hard segregationists used economic intimidation, sexual ixed violence, and terror to derail desegregation and destroy the developing black freedom movement. Between the Montgomery bus boycott and the student sit-in movement in 1960, African Americans hoping to re-create the Montgomery experience faced the forces of Jim Crow, sparking some of the fiercest battles for manhood and womanhood of the modern civil rights movement. THE SEVENTH-GRADE TEACHER AT Dunbar Junior High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, dismissed her students early on May 17, 1954. News of the historic Supreme Court decision strik- ing down segregation in public schools had just hit the airwaves, and she feared a violent white response. As students streamed out of the all-black school, she urged them to "pay attention to where you're walking, Walk in groups, don't walk alone." "Hurry," she added. Melba Patillo, a twelve-year-old African-American student Dunbar, wondered what all the fuss was about. Still, Melba was happy to have the afternoon free. She gathered her books and started on the route she had taken home for nearly six years. According to her autobiography, published several decades later, the meandered through a grassy stretch of blooming persimmon trees and daydreamed about becoming a movie star and moving to New York or California The sound of rustling leaves snapped her back to reality. She stopped and listened carefully, straining to see through the thick flora. Suddenly a deep voice sliced through the brush. "You want 136 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 137 Melba Patillo Melba Parillo arrived home, shaken and disheveled. She told her grandmother that a white man attempted to rape her. Patil- lo's grandmother, who loved to garden and read Shakespeare and Langston Hughes, listened and then quietly shuttled Melba to the bathroom and started a bath. "You sok a while, child. When the water goes down the drain, it will take all that white man's evil with it." Melba sat in the tub for what seemed like hours, listen- ing to the muffled voices of her parents and grandmother argu- ing about whether they should call the police. When she finally emerged, her family encouraged her not to feel ashamed about the attack. Her father, Howell Patillo, an enormous man who worked us a hostler's assistant on the Missouri Pacific Railroad, reached for Melba and pulled her close. "We ain't gonna call the law," he said. "Those white police are liable to do something worse to her than what already happened." Survival sometimes required that silence surround sexual violence, especially in an environment poisoned by the fierce backlash to Brown. Eventually Melbu would tell her story of the struggle in Little Rock for students across the coun try, but silence was not the only choice. Between 1996 and 1959. sex and sexual violence at at the center of the freedom struggle. and African Americans deployed different strategies to carry the movement through a crucial and difficult transition, including testimony, armed self-defense, and international pressure. a ride, girl?" She could not see anyone. Then it came again. Want a ride?" "Who is it?" she asked nervously "I got candy in the car," a man's gruvelly voice sang out. "Lots of candy. "Patillo inched forward and saw a burly white man com ing toward her. She turned and fled in the opposite direction, screaming for help and running as fast as her black-and-white sal dle shoes could carry her. "You better come and take a ride home, he growled. "You hear me, girl?" He was a huge man, Patillo recalled later, built "like a wre tler." He chased Patillo through the wooded path, screaming about "niggers wanting to go to school with his children and how he wasn't going to stand for it." Suddenly Patillo tripped on her shoelaces and fell. As she struggled to stand, he grabbed her shoul. ders, thrust her to the ground, and flipped her over on her back. "He slapped me hard across the face," she said in her memoir, then pinned her down and began fumbling with his belt buckle." "TH show you niggers the Supreme Court can't run my life," he said as he reached under Patillo's dress and ripped off her underwear. In her account, she scrambled out from underneath him and started to run. In the decide before Broww, African Americans in Little Rock, Arkansas, and throughout the South had testified openly about white attacks on black women. In the 1940s, for example, Daisy Bates, the acclaimed freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock Nine, used the power of the Arawa State Press, the newspaper she and her husband, LC. Bates, owned, to call attention to the long history of white-on-black rape. Like Rosa Parks, Bates was a mil- tant activist long before she orchestrated a showdown between Governor Orval Faubus and the federal government over the inte gration of Central High School in 1957. Her newspaper became a 139 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET thorn in the sides of Little Rock's white and black leaders, whom she pilloried regularly for failing to remedy the injustices of Jim Crow, especially police brutality and the abuse of black women. For Bates, rape was not just a political and legal issue that required state and community action, it was personal. When Daisy Bates was just was seven years old, three white men brutally raped and murdered her mother. Bates's father blamed the attack on the "timeworn lust of the white man." She was "not the kind to submit," he explained to his daughter, "so they took her. Overwhelmed by guilt and pain, he abandoned Daisy at a young age. She vowed revenge. "Young as I was, strange as it may seem," Daisy Bates wrote in her memoir years later, "my "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW life now had a secret goal--to find the men who had done this hor- rible thing to my mother." The whole ordeal left her feeling like a "little sapling, which, after a violent storm, puts out only gnarled and twisted branches." When she became older, Bates decided to transform her hatred and anger into positive action and make it count for something."* Over time the little sapling" became a towering oak: Bates became a fierce freedom fighter and leader of the Little Rock NAACP and in 1952 president of the Arkansas State Conference of NAACP branches. As an outspoken advocate for African Americans, Bates, like Rosa Parks, became known as the go-to person for victims of racial and sexual violence in Little Rock. She listened to them and scribbled notes, then placed their stories on the front page of her newspaper. The State Press became Bates's personal bullhorn, which she used to amplify demands for justice and voting rights and call for an end to the wanton sexual abuse of black women, Banner headlines between 1941 and 1955 made the crime public, helped to mobilize the black community, and alerted white offi- cials that crimes against black women would not go unnoticed For example, on July 17, 1942, the State Press published photo- graphs of two white Little Rock police officers who raped Rosa Lee Cherry, a nineteen-year-old African-American student at Dunbar High School. Daisy Bates even printed a transcript of Cherry's grand jury testimony. This helped secure public support for an indictment. Bates then argued that a conviction was necessary to save the great state of Arkansas." Although the white policemen walked free after their case ended in a mistrial, Bates's vigilance on the Cherry case and others like it made it impossible for white authorities to ignore crimes against African-American women. Her outspoken attacks on rape and other forms of sexualized vio- lence helped secure trials and, in some instances, even rare convic tions of white assailants who attacked black women in Arkansas during the 1940s and early 1950s." By 1954, however, a veil of secrecy had descended among African-American activists. In the years after Brouw, more than Daisy and LC. Bates and two police investigators examine a Ku Klux Klan crow left in their front yard in October 1956. Bates and her husband were targets of the Klan years before the Little Rock crisis began because of their vocal support for equality and justice for African-American rape victims in their newspaper, the Alta Press 140 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 141 EASTLAND half a million people opposed to integration and dedicated to white supremacy joined organizations like the White Citizens' Councils, the Ku Klux Klan, and the American States Rights Association, and launched an all-out war against the burgeoning freedom struggle. Death threats and dynamite blasts shook civil rights advocates across the region. The Patillos understood that the swirling storm of resistance that segregationists unleashed after Broww made silence about sexual violence a political impera tive Segregationist leaders throughout the South urged "massive resistance to Broww. They recruited supporters by denigrating the "traitorous" Supreme Court, while exploiting whites' fears about integration and interracial sexuality. U.S. News & World Report announced that many white Southerners opposed Brow because they feared "eventual amalgamation of the races-meaning mis- cegenation, intermarriage or whatever you want to call it." Judge Leander Perez, a political heavyweight in Louisiana, told support ers that the goal of integration was "miscegenation." "You make a Negro believe he is equal to the white people," he said, "and the first thing he wants is a white woman. And that's why there are so many criminal assaults and rapes." In a pamphlet titled you und Segregation, Georgia senator Herman Talmadge argued that the Almighty "Advocates Segregation," and warned that the ulti mate aim and goal of NAACP leaders... is the complete inter mingling of the nices in housing, schools, churches, public parks, public swimming pools and even in marriage." The Brow deci sion, he said, was "judicial tyranny" and "the greatest single blow ever... struck against constitutional government." "Resistance to tyranny," Mississippi senator James O. Bastland told white supporters, "is obedience to God. Walter Givhan, an Alabama state senator and ardent supporter of the White Citizens' Council, argued that desegregation was simply a ruse to open the bedroom doors of our white women to Negro men." Demagoguery of "miscegenation" fanned followers' fears to red-hot rage. Most did not explicitly advocate violence, but their Alabama state water Samuel Englehunde, Jr, an ardent segregationist and member of the White Citizens Council, promotes a white only anti integrationally extremist rhetoric undoubtedly encouraged it. Some politicians could not hold back. "A few killings now," a Mississippi legisla tor boasted, could save a lot of bloodshed then." At a massive Citizens' Council rally in Alabama, Senator Eastland cheered on the white mob that blocked Autherine Lucy, an African-American woman, from attending the University of Alabama in February 1956. He praised them for not letting the "NAACP run your schools." Southern whites, he told the audience, were "obligated to defy" Brow. When some whites responded by launching campaigns of violence and terror, many of those legislators stood silent, offering tacit approval while protecting themselves from blame Other political leaders fully supported the White Citizens' Council and its goals but worried that violence could hurt the seg regationists' cause. J. P. Coleman, the pragmatic governor who led Mississippi between 1956 and 1960, feared that defiance of federal law would hurt the state's standing in the national Democratic Party or provoke federal intervention. Coleman hoped to achieve the same goals as Eastland and other radicals through what he 142 143 AT THE DARK END OF THE STREET called "practical segregation." He pushed for the creation of a state agency that would mirror the FBI's investigative prowess and function as a public relations bureau. His goal was to "keep racial conflict out of the press while quietly and effectively man aging the state's fight against integration." Coleman tested the effectiveness of the newly formed State Sovereignty Commission in May 1956, when four white men from Tylertown, a small vil- lage in the Piney section of Mississippi, kidnapped a young black woman on the eve of her wedding and gang-raped her. It was just before dawn on May 13, 1956-Mother's Day when Ernest Dillon, a twenty-nine-year-old siding salesman; his brother Ollie, a middle-aged construction worker, and Olen and Durora Duncan, twenty-one-year-old cousins, went looking for "some colored women." Wielding a shotgun, Ernest Dillon approached Sennis Butler, a thirty-year-old black sharecropper who was outside preparing for the day's work. Dillon ordered him to take him and his friends to a home with black women inside. Annette Butler, a sixteen-year-old high school student, was in bed with her mother when she heard someone pounding on the front door of their two-bedroom home. Ernest Dillon introduced himself as a policeman. "You're under arrest," he said to the girl, for "sacking up with your boyfriend." When her mother objected, Dillon raised the shotgun, grabbed the teenager, and pulled her outside. He kept the shotgun trained on the girl's mother as his brother pushed her into the backseat of the car. Olen Duncan revved the engine and drove away, leaving Butler's mother alone in the front yard." The four white men drove Butler deep into the Bogue Chitto swamp, where they took turns raping her. Olen Duncan threar- ened to cut her neck off" if she resisted. "I followed his instruc- tions," she testified at the trial. When they finished, the four white men piled into the car and left Annette stranded in the woods. Wandering through the swamp half naked, she stumbled upon a group of black fishermen and ran to them for help. They led "THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW her out of the woods and delivered her to the police. Sheriff A.E. (Bill) Andrews took her complaint and then drove her home to get dressed. Later that day Sheriff Andrews brought Olen Duncan in for questioning, and he willingly signed a statement testifying that he had had "intimate relations" with Annette Butler. "It was done with every safeguard for the right of the defendant," Sheriff Andrews said, "after (Duncan] had been repeatedly advised that anything he might say could be used against him."** A few days later District Attorney Michael Carr charged all four men with "forcible ravishment and kidnap" and sent them to the Magnolia jail to await trial." Judge Tom Brady, a fierce white supremacist and one of the fathers of the White Citizens' Councils, presided over four sep arate trials in Pike County Circuit Court four months after the attack. The assailants must have wondered what kind of pun ishment Brady would impose since his public pronouncements against interracial mixing were already legendary. Time magazine called Brady the prophet" of segregation and his manifesto, Black Monday, the "Bible of the White Citizens' Council movement." When confronted with real interracial mixing and actual map ists, not the fictional black rapists he saw lurking behind every school-desegregation case, Brady buckled under the weight of his own racial prejudices. He appointed the "finest lawyers in Missis- sippi" to defend the four white assailants. Ernest Dillon may not have understood Brady's gesture, since he pleaded guilty on March 26, 1957, to the lesser charge of "assault with intent to rape." It was a risky plea that left his co-conspirators vulnerable. On the other hand, the plea bargain released him from trial and from the threat of the death penalty or life imprisonmentthe state's only punishments for rape. It also freed the jurors from having to declare a white man guilty of raping a black woman and defused any complaints of unequal justice or outside criticism of the state. It is likely that Dillon believed he would receive a minor sentence or even a suspended ute or death for rope ??? 16 145 feel that ne Nene Wie within the bounds of her own A group of Hacker On April 9 Buy wynhand her. By die for being Secondi comunity and mandhari She forwacking Austin, Jade AT THE END OF THE STREET willy, the pledeal wake for everyone of course On April 4 Olen Duncan, described by the ME Juru sender man with facial skin palied to deal white, surprised the packed Courtroom by pleading nee guilty despite his previously signed in His declaration of innocence fueled day of mense testimony Annette Butler tek the stand und pro easily identified as the driver and told the jury lewe man her lead to pay Bukas spela juvenile delinquent, c'esgrilled her about her whesabots the night before the wack Butler mother that she had accompanied her mother and into a jake jene called a lie's house and you might Defense then called Gew. Will white man, to estily about the tal reputation of Butler," segoed," he said with out hesitation. They did the king wy Aincan America retumber of white men who wed thu Olen Du Can's sure was impressive." Michael Carr, the duty, why to commider Duncan'da ve all the gibt the four ment became she was cay, Bergued, but because the is placed in such far of we wind for her very Dee Dumond his friend's guilty ples weekerlier, the all-white, all-male jury unanimously quite Ole Dance On April Jude Beady declared when 's cousin, Duro Duncan also pleaded guilheydew News of the wall wil infuriated group of African-America, who were the Mel They criticized the informitting companhellum did we co the criminal which was comme widowingine.comland hash way of light be wearificium Nighly do in the Map See Andy Whiseade.com Dichida mot discriminate the Meyes MEG here, the chairman of the legislatie meting commit of the SS Comme ved," he wider wild a cool, jury is way life imprime for the charge pou The sheriff McGehend and the theople of Missippi chikach crimes with all his crimes heid, eeben, Weedingles in its wake." The weed markow, and our people where there encefice of this arealent and dutiful and that the evidence was taken with dead to the credit of the people of Pen Well Cid Mini well. By giving my youn, July Brady and the enigny Came the weet we will believed in and onder Eept when they didn't. The lengthy jail cedido white from being Wacke in Mippie chewhere. Giti Council members, Klam, and the Afrin Action over the phone on them, and in public places Hune mail per aktiviti alle kope their phonesringing through the nigh. Bo Pales, for cumple comeceived call from any who who yelledieng- when she help the other black cocher, Rosa Puso her job and was blacklisted in Montgomery, wer husband and mother. Ahily with that in the sum. mer of 1957. Purles called her sin in Detroit sobbing." get the hell out of Money, hey " Rodrig those who locate degree or wing righe-withese wil hus, we knuckles, time, my chain, and the imple sofore. I the Missippi Dela white men under che Mack malesia 1955: In Maywhites mund the Re and George Lee for giring women. In August, Lana Smith, sixty-year-old fammer, was killed in bed delighed for Laner hur math.J. W. Miland med fill in Money, Mi Till, Chicago native in Mihinde Me Wright, companindrop of children to be 's Grocery and Me Marker pune candy black yangter allegedly lined with Beyan's young wie se purchasing some blegum Touriger Boy By J. W. Milam kidipped immen Til brutally beat him, and then his neck with bar wire the chie River Afisherman med Tills body and sold the mutiled.com the tive dhe days to me prie photos of the meaning the end the NAP launched in camp for Still, Parks knew theme and economic intimidation were the limits of where Sleeplering her 2 For mother they made them William Bradlied Haie for an article in manier om the Augas femen. "Where to me timing with a white w Budhi wigilantes stumed bombing Wack homes, churches, and be is Montgomery Dynamite damaged or destroyed the homes and churches of promise and bu ce van Ralph Abemuty, Robert Grand Martin Luther King Jr. In Birmingham at www.cne bombings directed Wade between 1955 and 1958 tumed the Magic Geyim"Bob inghem in small towns and cities that the South, white mebebeat indtil African Americnspecially They've and pekerwed who wants can poster The NAACP demanded punishment for the shacking des CHAPTER 4 "There's Open Season on Negroes Now" THE SEVENTH-GRADE TEACHER AT Dunbar Junior High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, dismissed her students early on May 17, 1954. News of the historic Supreme Court decision strik- ing down segregation in public schools had just hit the airwaves, and she feared a violent white response. As students streamed out of the all-black school, she urged them to pay attention to where you're walking. Walk in groups, don't walk alone." "Hurry," she added. Melba Patillo, a twelve-year-old African-American student at Dunbar, wondered what all the fuss was about. Still, Melba was happy to have the afternoon free. She gathered her books and started on the route she had taken home for nearly six years. According to her autobiography, published several decades later, the meandered through a grassy stretch of blooming persimmon trees and daydreamed about becoming a movie star and moving to New York or California. The sound of rustling leaves snapped her back to reality. She scopped and listened carefully, straining to see through the thick Hora. Suddenly a deep voice sliced through the brush. "You want Melba Patillo a ride, girl?" She could not see anyone. Then it came again. "Want a ride?" "Who is it?" she asked nervously. "I got candy in the car," a man's gravelly voice sang out. "Lots of candy." Patillo inched forward and saw a burly white man com ing toward her. She turned and fled in the opposite direction, screaming for help and running as fast as her black-and-white sad- dle shoes could carry her. "You better come and take a ride home," he growled. "You hear me, girl?"* He was a "huge" man, Patillo recalled later, built "like a wres tler." He chased Patillo through the wooded path, screaming about "niggers wanting to go to school with his children and how he wasn't going to stand for it." Suddenly Patillo tripped on her shoelaces and fell. As she struggled to stand, he grabbed her shoul- ders, thrust her to the ground, and flipped her over on her back. "He slapped me hard across the face," she said in her memoir, then pinned her down and began fumbling with his belt buckle. "TII show you niggers the Supreme Court can't run my life," he said as he reached under Patillo's dress and ripped off her underwear. In her account, she scrambled out from underneath him and started to run. *THERE'S OPEN SEASON ON NEGROES NOW 137 Melba Patillo arrived home, shaken and disheveled. She told her grandmother that a white man attempted to rape her. Patil lo's grandmother, who loved to garden and read Shakespeare and Langston Hughes, listened and then quietly shuttled Melba to the bathroom and started a bath. "You soak a while, child. When the water goes down the drain, it will take all that white man's evil with it." Melba sat in the tub for what seemed like hours, listen- ing to the muffled voices of her parents and grandmother argu- ing about whether they should call the police. When she finally emerged, her family encouraged her not to feel ashamed about the attack. Her father, Howell Patillo, an enormous man who worked as a hostler's assistant on the Missouri Pacific Railroad, reached for Melba and pulled her close. "We ain't gonna call the law," he said. "Those white police are liable to do something worse to her than what already happened." Survival sometimes required that silence surround sexual violence, especially in an environment poisoned by the fierce backlash to Brown. Eventually Melba would tell her story of the struggle in Little Rock for students across the coun- try, but silence was not the only choice. Between 1956 and 1959, sex and sexual violence sat at the center of the freedom struggle, and African Americans deployed different strategies to carry