I need help with compiling an executive memo to the CEO of ConAgra arguing for or against a stock market valuation focus at the current time (contemporaneous with the case which was in 2002). Note that I am not supposed to be making a case for including stock price among the CEO's concerns--I am arguing for him to either make it his primary focus or not at the present time of the case. I have to also include at least a brief discussion of the supply chain in this assessment/recommendation. I am not sure if I should be arguing for or against making the stock market valuation the CEO's focus. Below are the pages of the case study that has pertinent information regarding the stock valuation and financials.

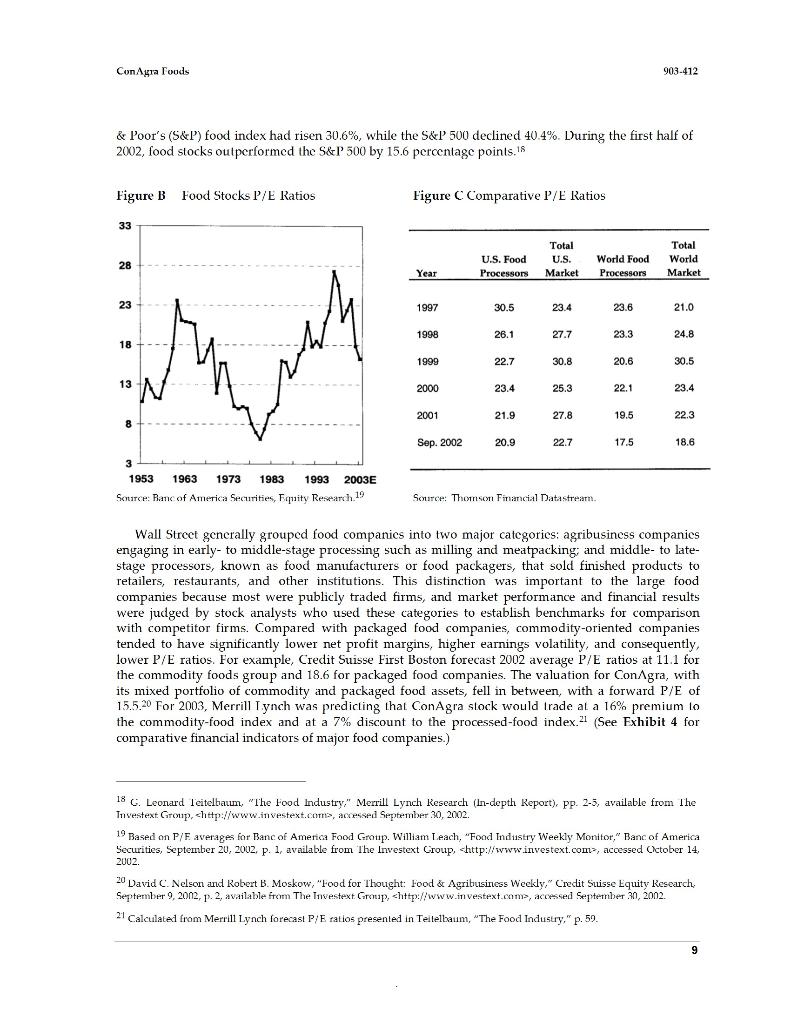

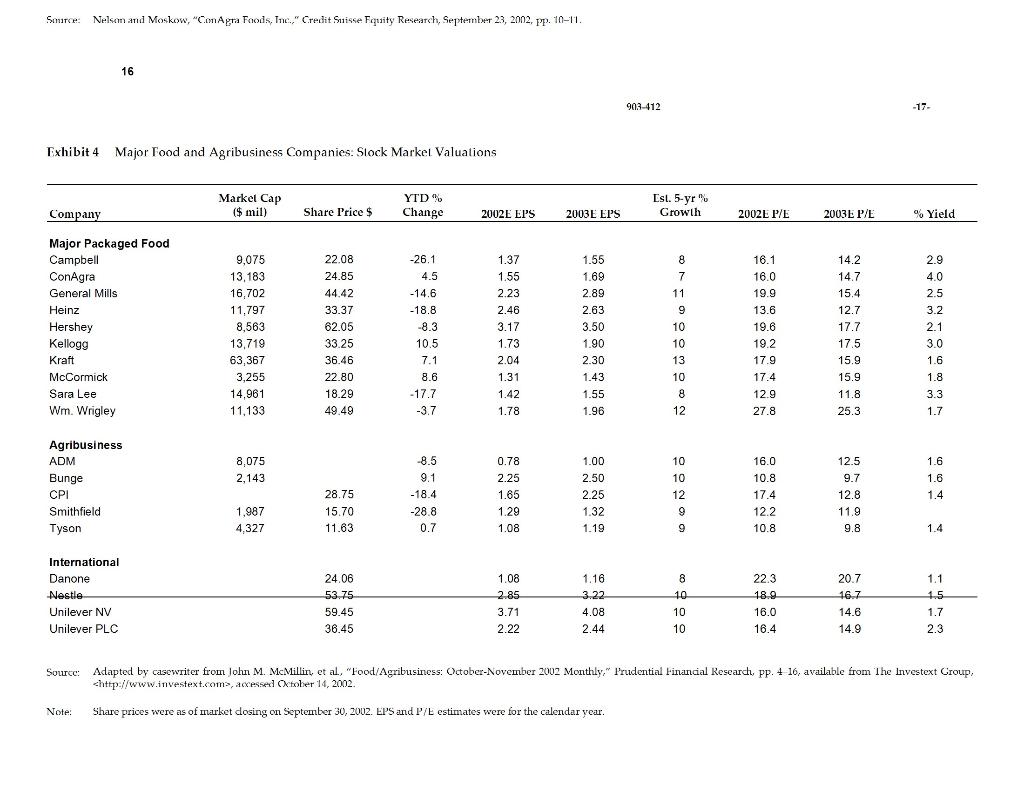

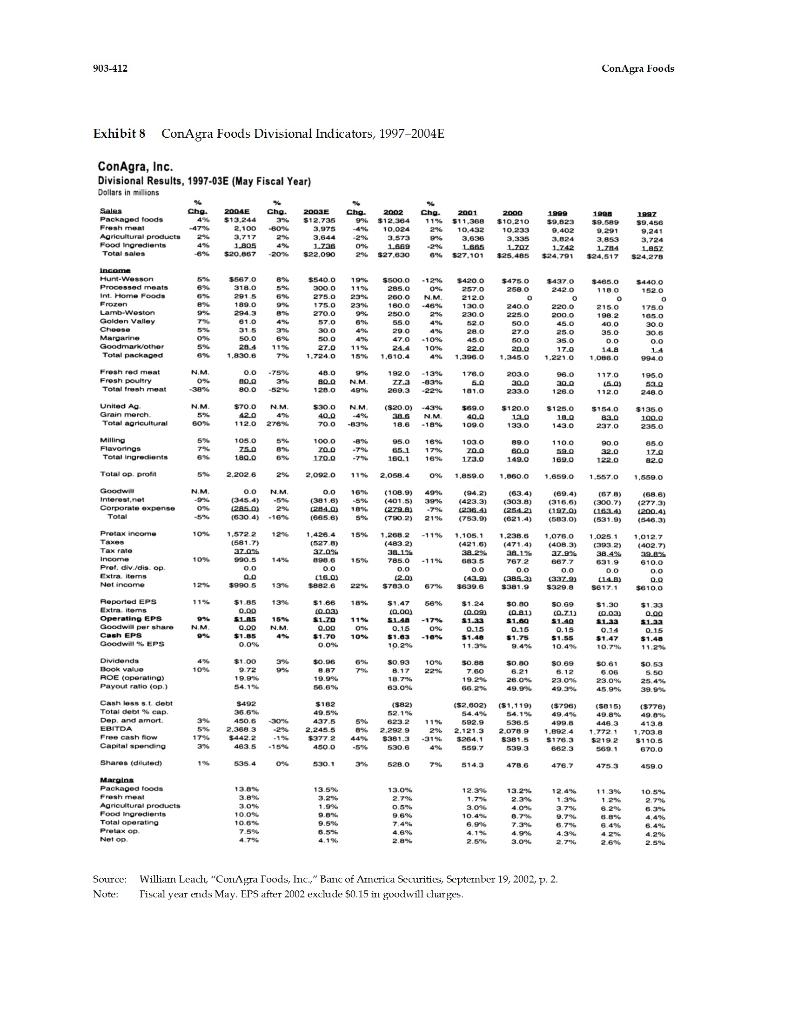

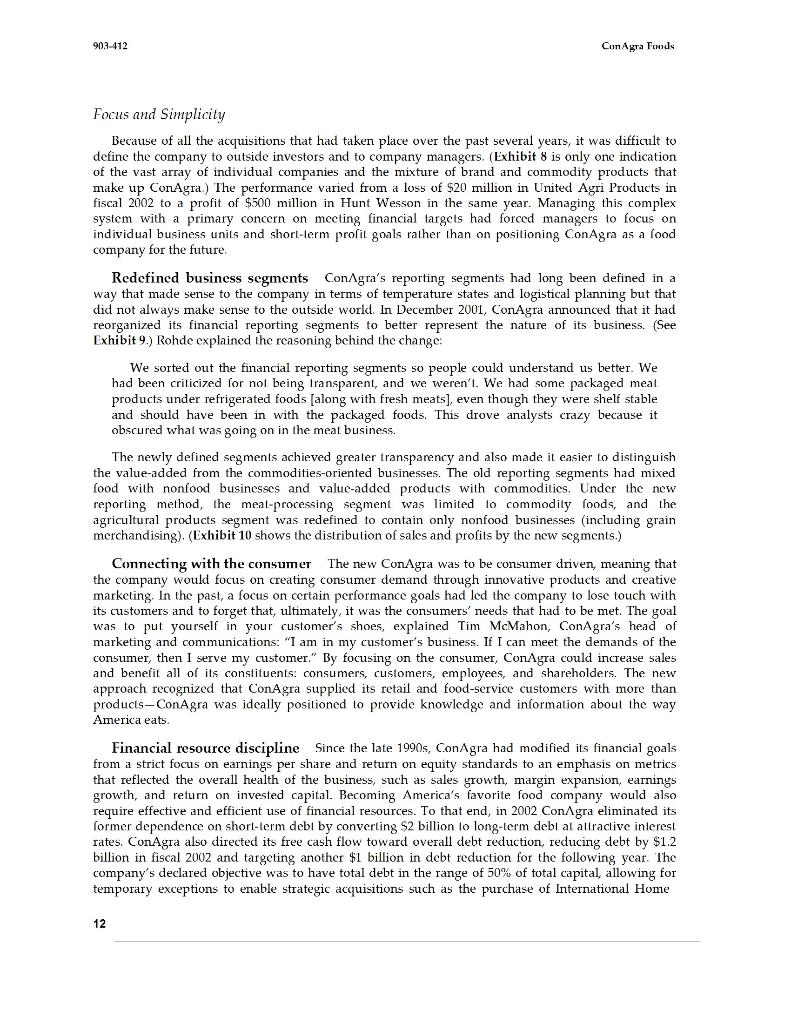

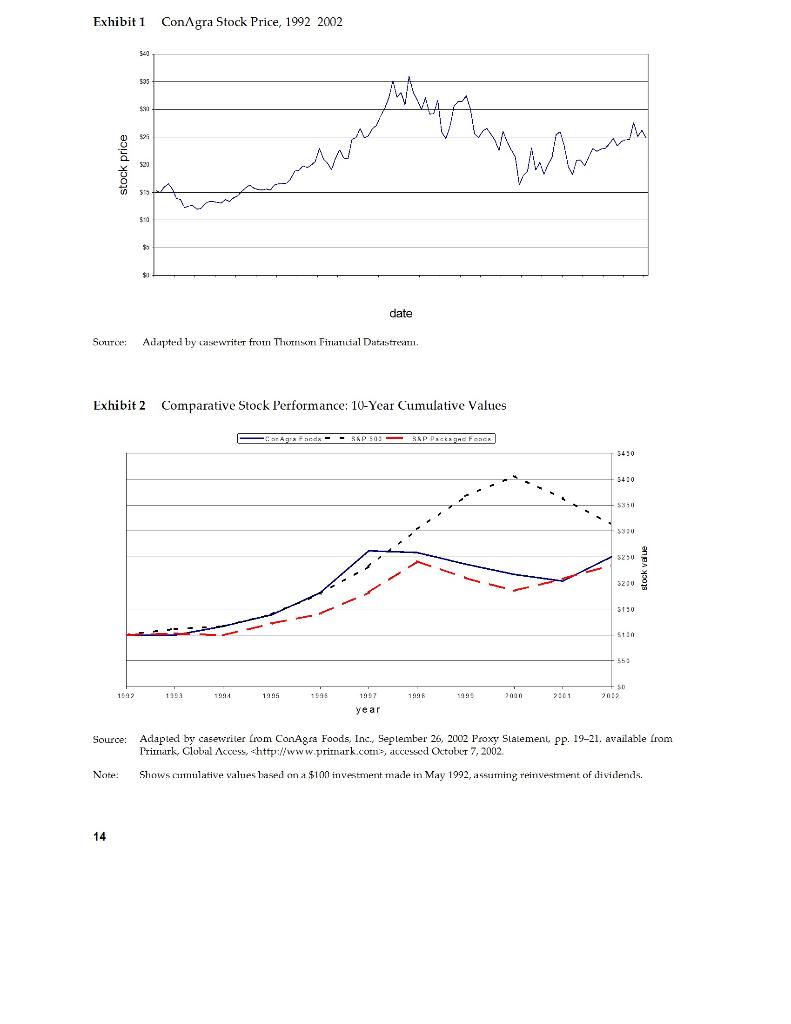

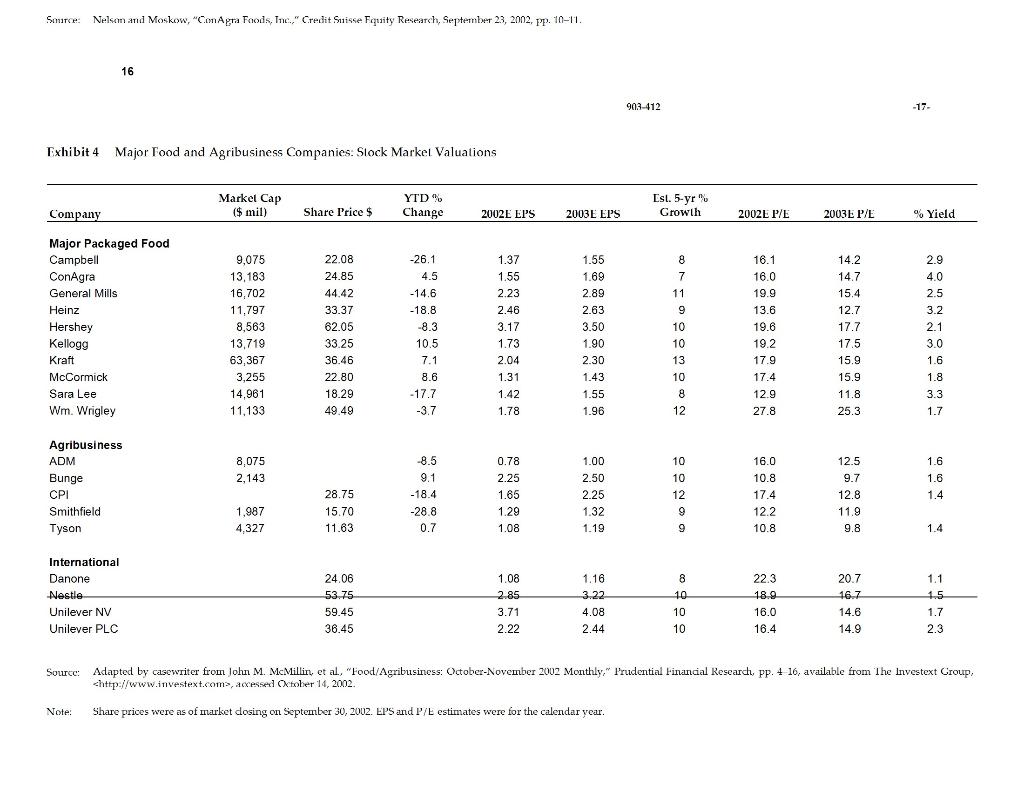

903-412 ConAgra Foods Rohde placed the pace of industry consolidation at the top of the list of challenges for the company. Customers in both retail and food services were highly consolidated, and ConAgra's competitors were following suit. ConAgra itself was the product of decades of acquisitions, the most recent major deal being the S2.9 billion purchase of International Home Foods in 2000, which added several popular brands to ConAgra's portfolio. But until recently, ConAgra's growth had not been combined with an effective consolidation strategy, and Rohde realized that the company was out of synch with its customer base. "From the client's perspective, ConAgra was too cumbersome and difficult to do business with," he said. Correcting this situation became a company priority. Biotechnology The dramatic worldwide growth in farming productivity since the 1960s was made possible by improved fertilization, crop management, and especially the development of scientifically enhanced seeds. The crossbreeding techniques originally used to improve crops were later replaced by genetic engineering of seeds, a process known as bioengineering, or biotechnology. Agricultural biolech- nology was primarily used to develop insect- and disease-resistant crops. One of the most successful innovations had been Monsanto Company's Roundup Ready variety of corn and soybeans. These " crops were resistant to Monsanto's top-selling herbicide, making it easier for farmers to keep their fields free of weeds with less need for chemicals and filling Products developed through genetic engineering by other companies included crops resistant to pests, cold, and drought; fruits and vegetables with longer shelf lives; and pigs with reduced fai content. Also on the horizon were nutritionally enhanced consumer products such as proteins fortified with beneficial Omega-3 (ally acids. Biotechnology advocates argued that genetic engineering held the solution to effectively feeding the world's ever-expanding population. Genetically engineered crops could also benefit the environment by limiling the acreage needed for planling, thereby preventing deforestation and soil erosion Opponents expressed concern that pest-resistant crops could lead to the development of "super insects" capable of resisting both new and conventional controls. Vocal opposition also came from consumer groups, especially in Europe, that feared laboratory tampering with foods. Consumer suspicion of genetically modified foods threatened to slow the advent of new products or relegate them to nonhuman consumption, in animal feeds for example. Increasingly, however, the public was realizing that biotechnology was not just genetically modified organisms (GMOs) but rather a method for improving the quality and nutritionally sound use of food. ConAgra had just begun exploring the role of biotechnology in the company's future. Rohde was convinced that biotechnology could not only reduce environmental damage but also lead to important nutritional breakthroughs that would benefit consumers. Ultimately, he knew, it would be up to the consumers to decide biotechnology's role in the food business: If customers demanded biotech products, ConAgra would provide them. Slock Valuations U.S. food stocks hit an all-time high in 1997, when shares in food-processing companies were trading at a 30% premium to the overall stock market. The high valuation of food stocks was due largely to earnings growth from expanding international markets, so when the Asian currency crisis hit in 1998, food price-to-carnings (P/E) ratios dropped markedly. Food stocks showed signs of recovery beginning in 2000, as a weakened U.S. economy and plummeting technology stocks sent investors running to traditional business sectors, but the overall trend continued downward. (See Figures B and C.) Nevertheless, since the peak of the technology bubble in March 2000, the Standard Con Agra Foods 903-412 & Poor's (S&P) food index had risen 30.6%, while the S&P 500 declined 40.4%. During the first half of 2002, food stocks outperformed the S&P 500 by 15.6 percentage points. 18 Figure B Food Stocks P/E Ratios / Figure C Comparative P/E Ratios 33 Total U.S. U.S. Food Processors 28 Total World Market World Food Processors Year Market 23 1997 30.5 23.4 23.6 21.0 1998 26.1 27.7 23.3 24.8 18 1999 22.7 30.8 20.6 30.5 13 2000 23.4 25.3 22.1 23.4 2001 21.9 27.8 19.5 22.3 8 Sep. 2002 20.9 22.7 17.5 18.6 3 1953 1963 1973 1983 1993 2003E Source: Ranc of America Securities, Equity Research.19 Source: Thomson Financial Datastream. Wall Street generally grouped food companies into two major categories: agribusiness companies engaging in early- to middle-stage processing such as milling and meatpacking and middle- to late- stage processors, known as food manufacturers or food packagers, that sold finished products to retailers, restaurants, and other institutions. This distinction was important to the large food companies because most were publicly traded firms, and market performance and financial results were judged by stock analysts who used these categories to establish benchmarks for comparison with competitor firms. Compared with packaged food companies, commodity-oriented companies tended to have significantly lower net profit margins, higher earnings volatility, and consequently, lower P/E ratios. For example, Credit Suisse First Boston forecast 2002 average P/E ratios at 11.1 for the commodity foods group and 18.6 for packaged food companies. The valuation for ConAgra, with its mixed portfolio of commodity and packaged food assets, fell in between, with a forward P/E of 15.5.20 For 2003, Merrill Lynch was predicting that ConAgra stock would trade at a 16% premium lo the commodity-food index and at a 7% discount to the processed-food index 21 (See Exhibit 4 for comparative financial indicators of major food companies.) a 18 G. Leonard leitelbaum, "The Food Industry," Merrill Lynch Research (In-depth Report), PP. 2-5, available from The Investext Group

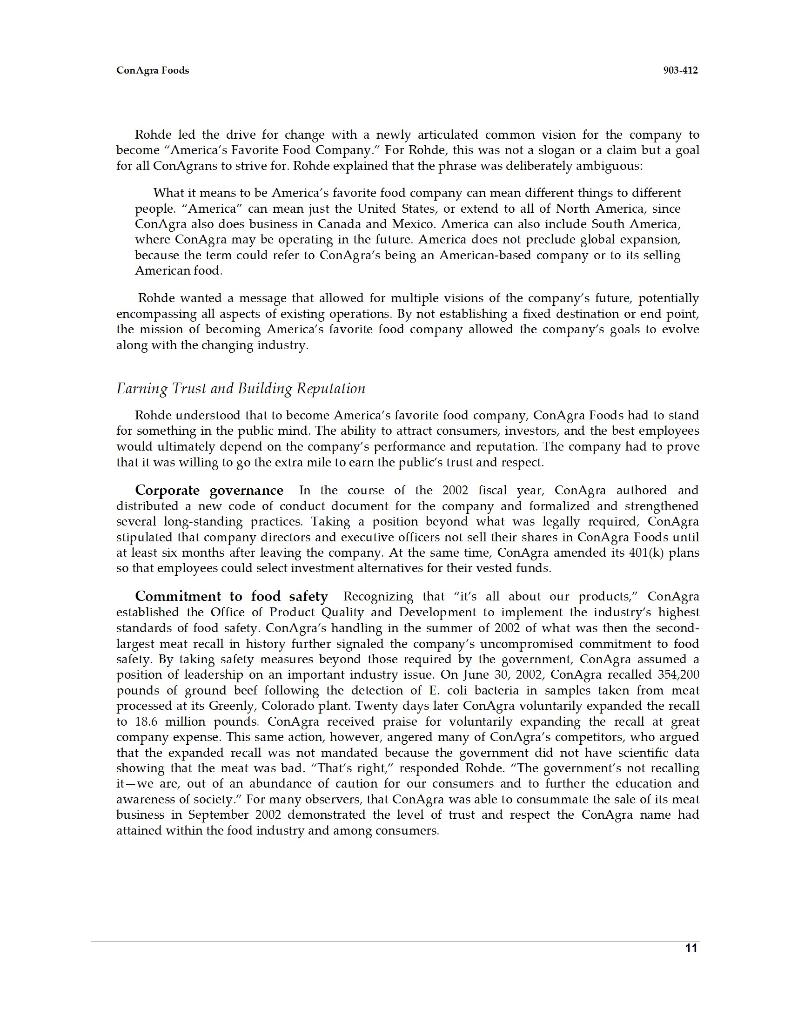

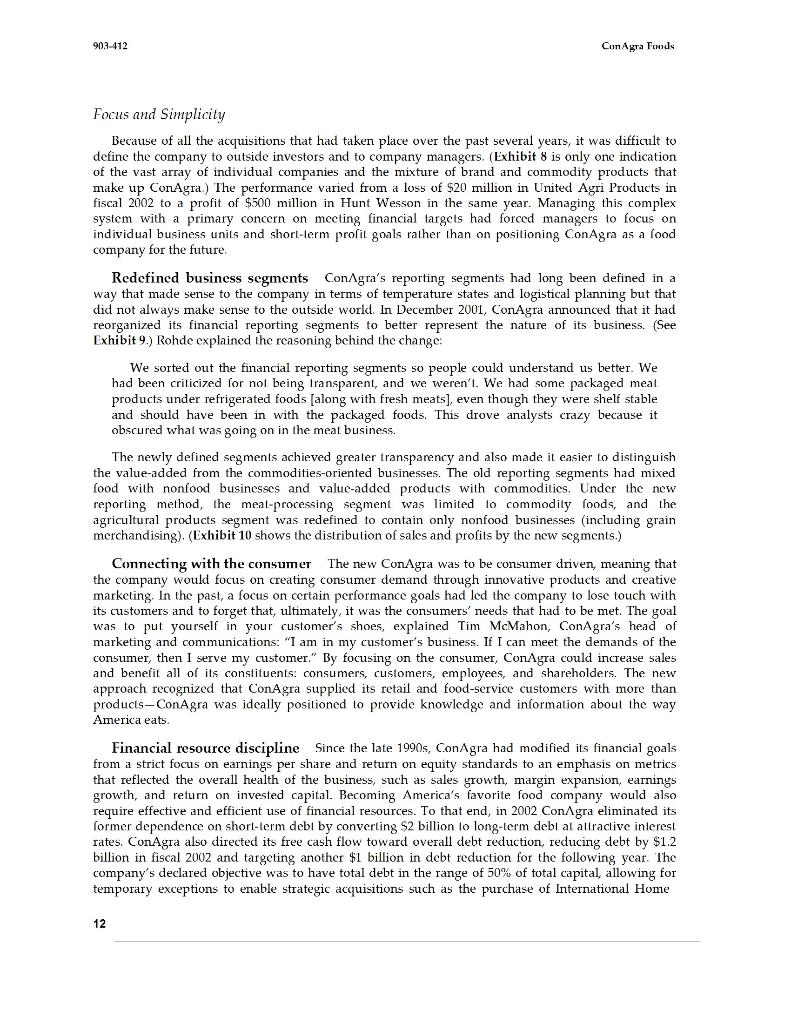

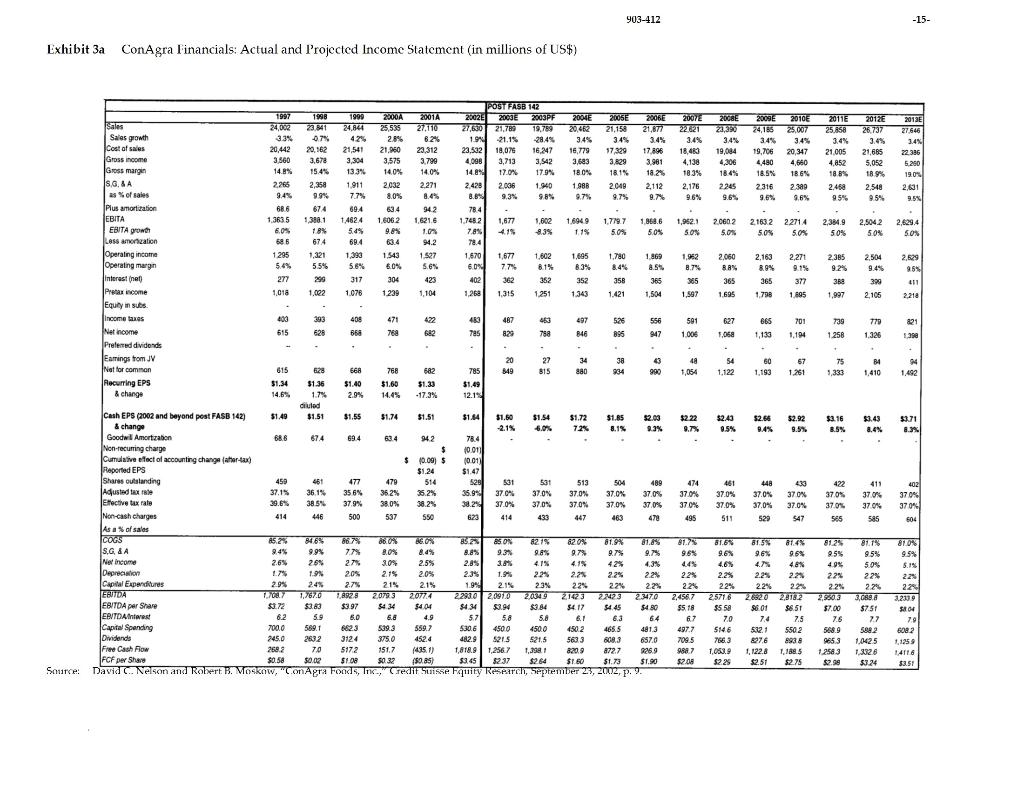

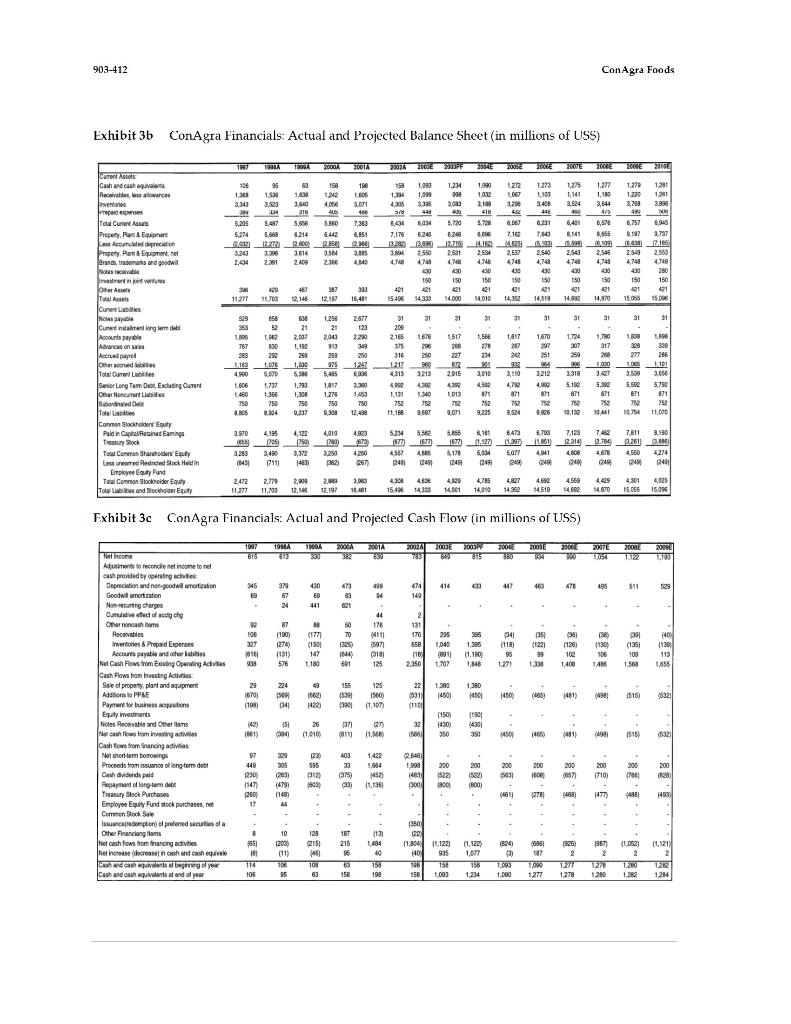

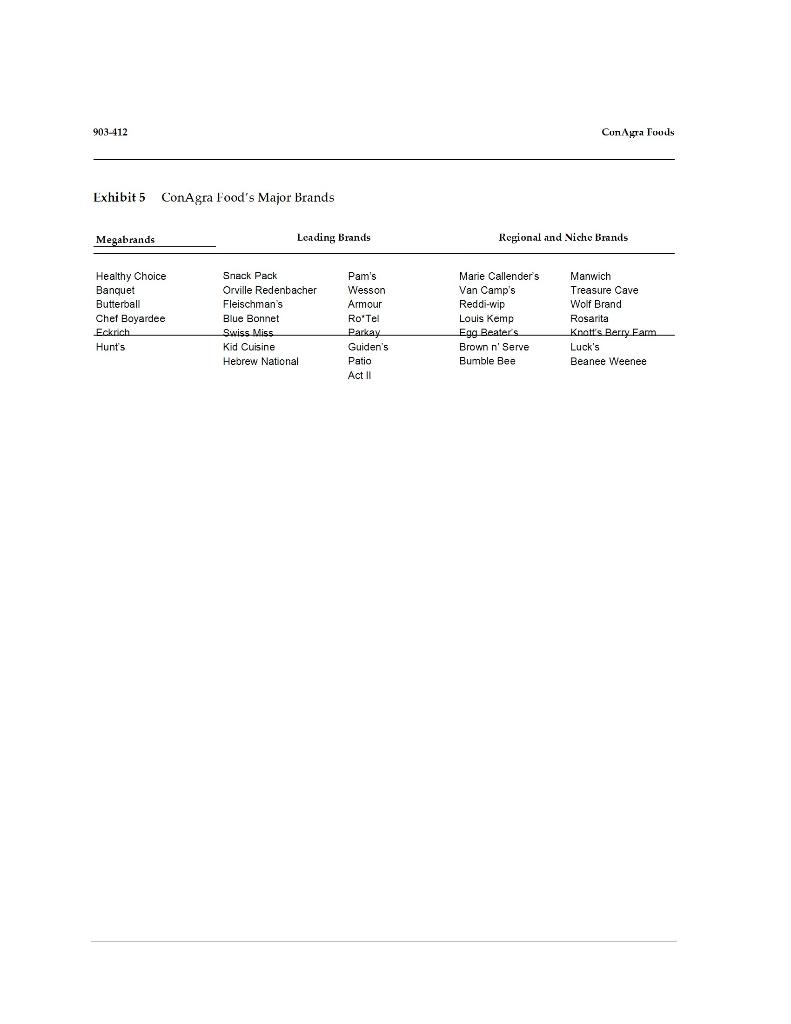

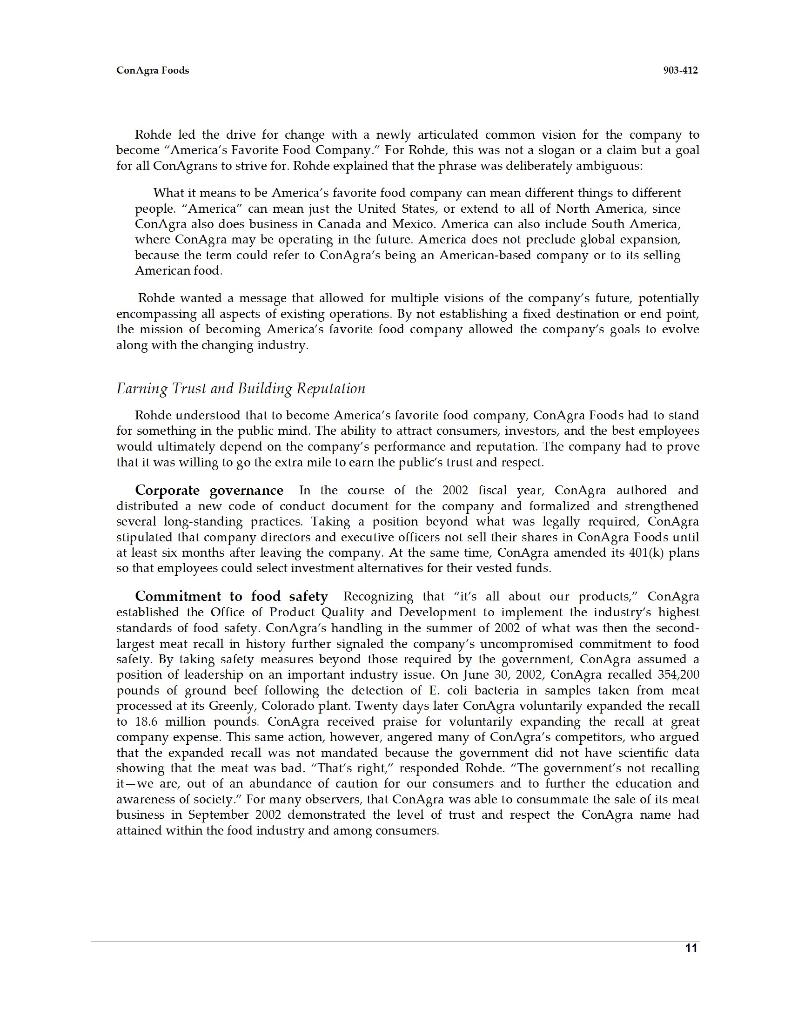

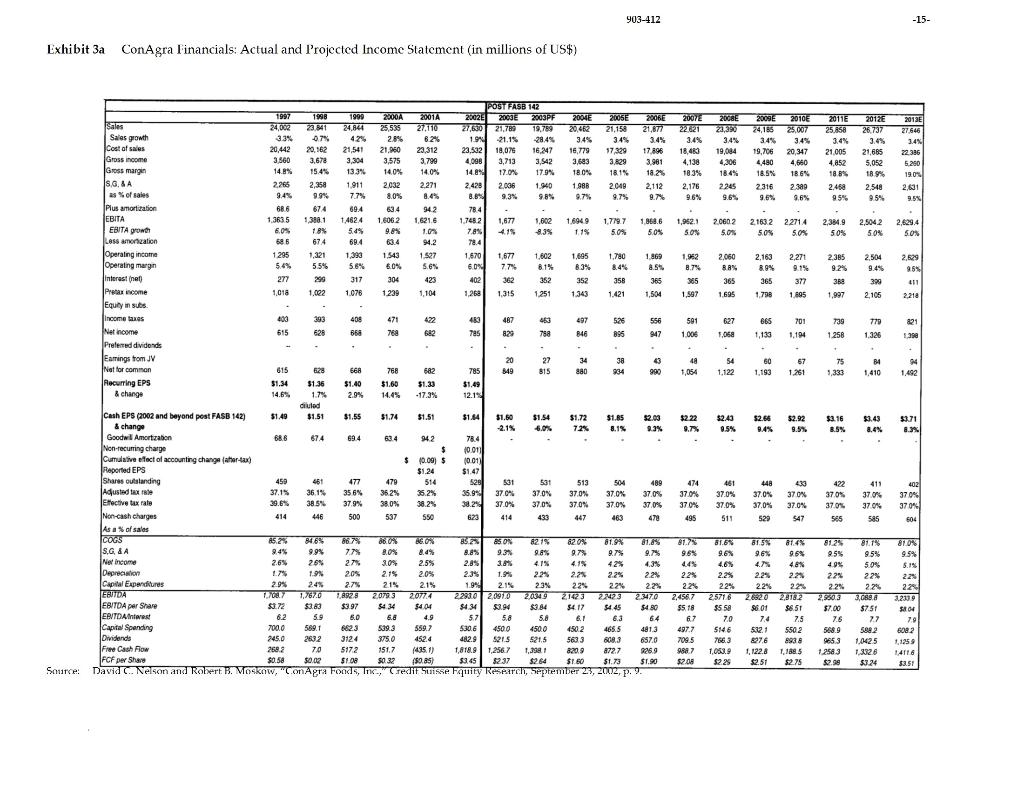

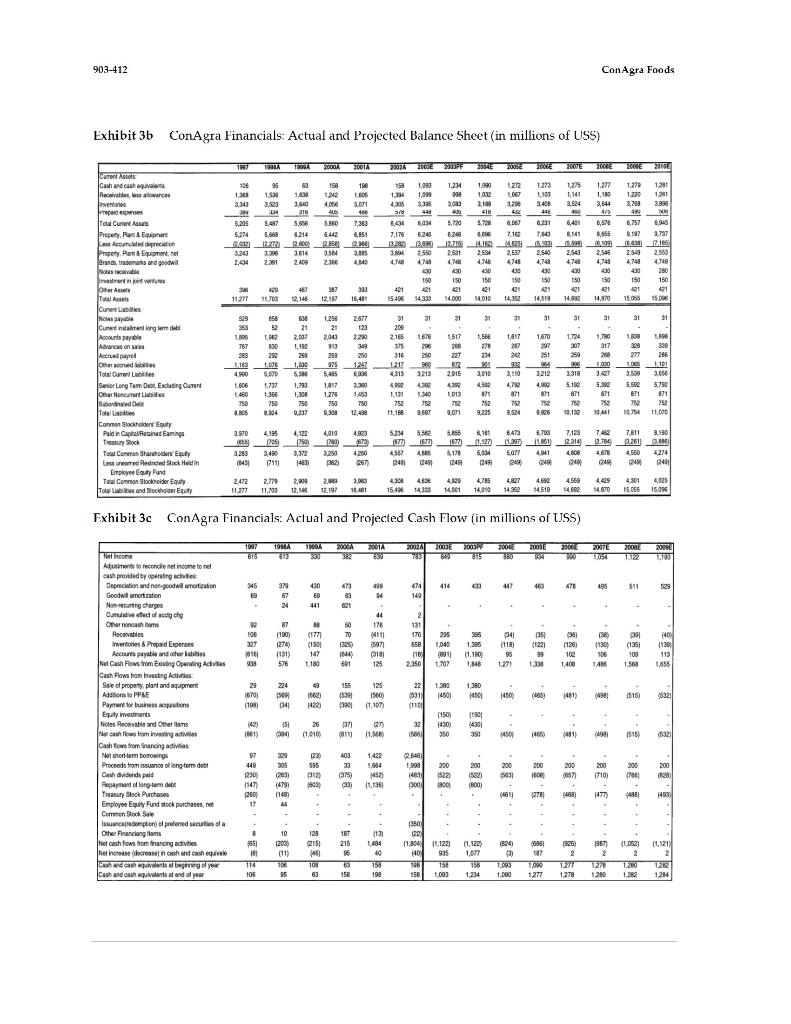

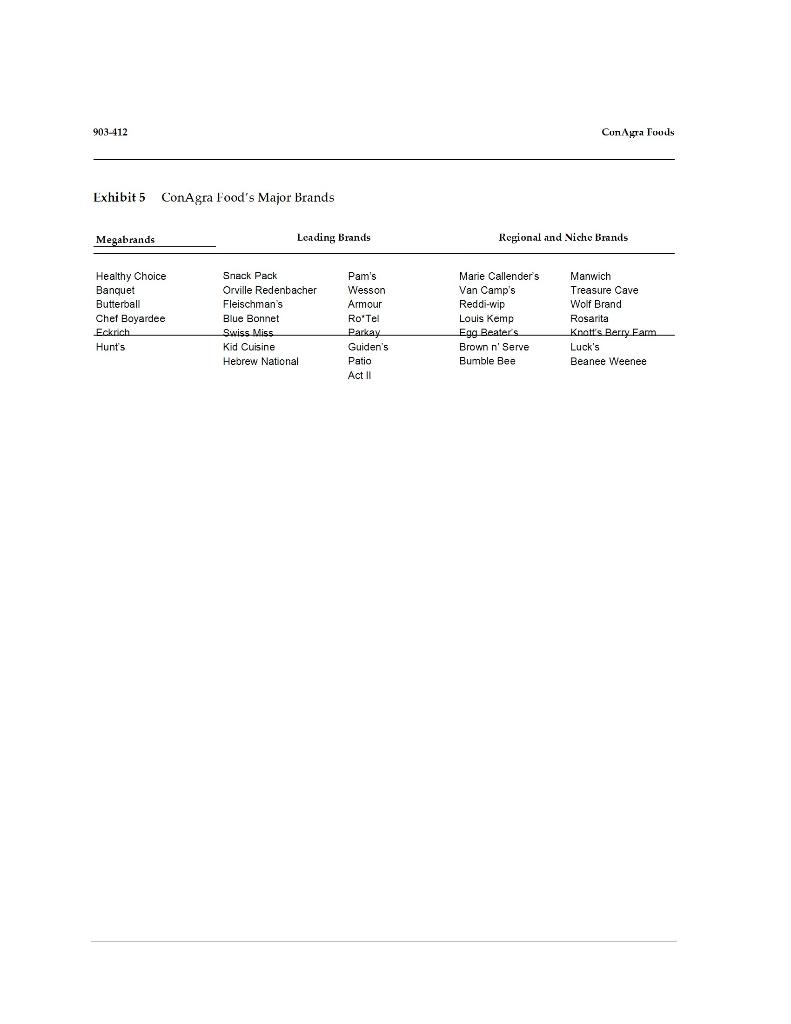

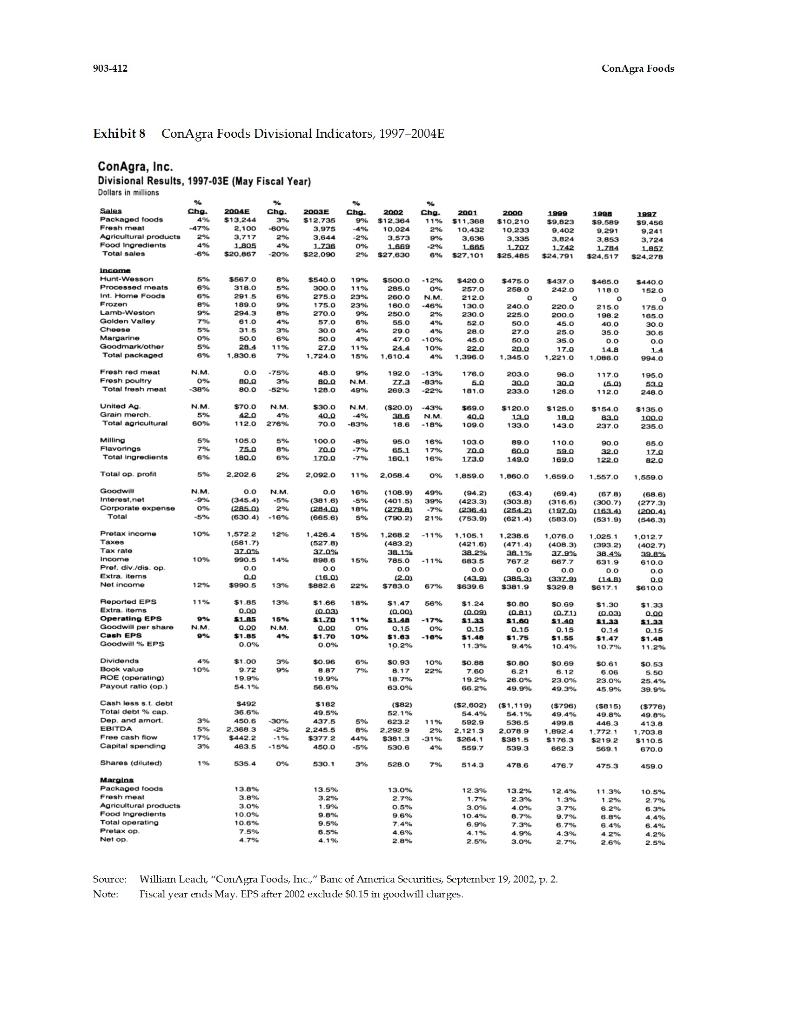

accessed October 14, 2002 20 David C. Nelson and Robert B. Moskow, "Food for Thought: Food & Agribusiness Weekly," Credit Suisse Equity Research, September 9, 2012, p. 2, available from The Investext Grenap, , accessed September 30, 2002. 21 Calculated from Merrill Lynch forecast P/E ratlos presented in Teitelbaum, "The Food Industry," p. 59. 9 903-412 ConAgra Foods ConAgra held perhaps the most diversified position or any food company in the world, in that it operated at both ends of the food supply chain, from farm inputs to retail and food service. (In fact, ConAgra held the distinction of being counted within the packaged foods group at Credit Suisse, while at the same time being included in Merrill Lynch's commodity index.) In the past, ConAgra had often heralded its "farm gate to dinner plate" character as a unique advantage to the company, providing increased opportunities for synergies and easing cyclical effects at either end of the business. More recently, however, the company was finding that ils unparalleled position in the industry was also a source of confusion for Wall Street, potential investors, and even its own employees as they tried to assess ConAgra's performance and future prospects. Introducing the New ConAgra Foods ConAgra had taken steps to promote teamwork and, through Operation Overdrive, was changing the structure of its internal operations, but the message that the old ConAgra was history had yet lo hit home-both inside and outside the company. Rohde was also concerned about ConAgra's persistent image as an agricultural conglomerate. A ConAgra executive in investor relations recalled that when he joined the company in 2000, "ConAgra carried the baggage of a commodity company image." Though by then the company had gone from just 16 brands in 1996 to 27 brands with annual retail sales of over $100 million each, investors were still more likely to compare Con gra with Cargill than with Krall. By 2002 ConAgra's portfelowhaide world struggling to understand the nature over 35 , of which are listed in Exhibit 5.) It was not just the outside of the company. ConAgra was going through an identity crisis, evidenced in the pages of its annual reports. The 1998 report described the company as operating "across the food chain," providing "products and services from farm gate to dinner plate." By 2000 the company had transformed into "the home of great brands and great taste, North America's largest foodservice supplier, and a strong basic foods business." Driving the message home was the annual report's front cover carrying the one-word question: "Hungry?" Directly below came the answer in the form of the company's new name: "ConAgra Foods." As the company assessed its opportunities in fiscal years 2000 and 2001, management knew that significant changes encompassing cultural , functional, and marketplace resources would be necessary to position the company io provide shareholders with strong uiure relurns. These changes, which the company described as "a transformation from an agribusiness giant to America's favorite food company," involved four major arcas: portfolio of businesses held by the company; sales and marketing excellence; infrastructure development, specifically with logistics and Mis; and resource deployment Becoming America's Favorite Food Company In 2000, ConAgra Inc. changed its name to ConAgra Foods, a move that drew little public notice since, after all, ConAgra was hardly a household name. Despite the prevalence of ConAgra products in kitchen cabinets across the country, few people knew "the good name behind the good names." A ConAgra Foods brand marketing campaign launched in 2001 set out to change that. Through print advertising, media spots, and the placing of the ConAgra Foods logo as a "trust mark" on all of its products, consumers would soon know the name of the company that made many of their favorite brands. (See Exhibits 6 and 7.) The ConAgra logo also appeared for the first time on subsidiary letterhead and business cards, delivering the image of ConAgra Foods as a single unified company internally and to everyone the company did business with. 10 ConAgra loods 903-412 Rohde led the drive for change with a newly articulated common vision for the company to become "America's Favorite Food Company." For Rohde, this was not a slogan or a claim but a goal for all ConAgrans to strive for. Rohde explained that the phrase was deliberately ambiguous: What it means to be America's favorite food company can mean different things different people. "America" can mean just the United States, or extend to all of North America, since ConAgra also does business in Canada and Mexico. America can also include South America, where ConAgra may be operating in the future. America does not preclude global expansion, because the term could refer to ConAgra's being an American-based company or to its selling American food Rohde wanted a message that allowed for multiple visions of the company's future, potentially encompassing all aspects of existing operations. By not establishing a fixed destination or end point, the mission of becoming America's favorite food company allowed the company's goals to evolve along with the changing industry. Carning Trust and Building Reputation Rohde understood that to become America's favorite food company, ConAgra Foods had to stand for something in the public mind. The ability to attract consumers, investors, and the best employees would ultimately depend on the company's performance and reputation. The company had to prove that willing to go the extra mile to earn the public's trust respect. Corporate governance in the course of the 2002 fiscal year, ConAgra authored and distributed a new code of conduct document for the company and formalized and strengthened several long-standing practices. Taking a position beyond what was legally required, ConAgra stipulated that company directors and executive officers not sell their shares in ConAgra Foods until at least six months after leaving the company. At the same time, ConAgra amended its 401(k) plans so that employees could select investment alternatives for their vested funds. Commitment to food safety Recognizing that "it's all about our products," ConAgra established the Office of Product Quality and Development to implement the industry's highest standards of food safety. ConAgra's handling in the summer of 2002 of what was then the second- largest meat recall in history further signaled the company's uncompromised commitment to food safely. By taking safety measures beyond those required by the government, ConAgra assumed a position of leadership on an important industry issue. On June 30, 2002, ConAgra recalled 354,200 , pounds of ground beef following the detection of E. coli bacteria in samples taken from meat processed at its Greenly, Colorado plant. Twenty days later ConAgra voluntarily expanded the recall to 18.6 million pounds. ConAgra received praise for voluntarily expanding the recall at great company expense. This same action, however, angered many of ConAgra's that the expanded recall was not mandated because the government did not have scientific data competitors, who argued showing that the meat was bad. "That's right," responded Rohde. "The government's not recalling it-we arc, out of an abundance of caution for our consumers and to further the education and awareness of society." For many observers, thal ConAgra was able to consummate the sale of its meal business in September 2002 demonstrated the level of trust and respect the ConAgra name had attained within the food industry and among consumers a 11 903 412 Con Agra Foods Focus and Simplicity Because of all the acquisitions that had taken place over the past several years, it was difficult to define the company to outside investors and to company managers. (Exhibit 8 is only one indication of the vast array of individual companies and the mixture of brand and commodity products that make up ConAgra.) The performance varied from a loss of $20 million in United Agri Products in fiscal 2002 to a profit of $500 million in Hunt Wesson in the same year. Managing this complex system with a primary concern on meeting financial targets had forced managers to focus on individual business units and short-term profit goals rather than on positioning ConAgra as a lood company for the future Redefined business segments Con gra's reporting segments had long been defined in a way that made sense to the company in terms of temperature states and logistical planning but that did not always make sense to the outside world. In December 2001, ConAgra announced that it had reorganized its financial reporting segments to better represent the nature of its business. (See Exhibit 9.) Rohde explained the reasoning behind the change: We sorted out the financial reporting segments so people could understand us better. We had been criticized for not being transparent, and we weren't. We had some packaged meat products under refrigerated foods (along with fresh meats), even though they were shelf stable and should have been in with the packaged foods. This drove analysts crazy because it obscured what was going on in the meat business. The newly defined segments achieved greater transparency and also made it easier to distinguish the value-added from the commodities-oriented businesses. The old reporting segments had mixed food with nonfood businesses and value-added products with commodities. Under the new reporting method, the meal-processing segment was limited to commodity foods, and the agricultural products segment was redefined to contain only nonfood businesses (including grain merchandising). (Exhibit 10 shows the distribution of sales and profits by the new segments.) Connecting with the consumer The new ConAgra was to be consumer driven, meaning that the company would focus on creating consumer demand through innovative products and creative marketing. In the past, a focus on certain performance goals had led the company to lose touch with its customers and to forget that, ultimately, it was the consumers' needs that had to be met. The goal was to put yourself in your customer's shoes, explained Tim McMahon, ConAgra's head of marketing and communications: "I am in my customer's business. If I can meet the demands of the consumer, then I serve my customer." By focusing on the consumer, ConAgra could increase sales and benefit all of ils constituents: consumers, customers, employees, and shareholders. The new approach recognized that ConAgra supplied its retail and food-service customers with more than products-ConAgra was idcally positioned to provide knowledge and information about the way America eats. Financial resource discipline Since the late 1990s, ConAgra had modified its financial goals from a strict focus on earnings per share and return on equity standards to an emphasis on metrics that reflected the overall health of the business, such as sales growth, margin expansion, earnings growth, and return on invested capital. Becoming America's favorite food company would also require effective and efficient use of financial resources. To that end, in 2002 ConAgra eliminated its former dependence on short-term debl by converting $2 billion to long-term debt at attractive interest rates. ConAgra also directed its free cash flow toward overall debt reduction, reducing debt by $1.2 billion in fiscal 2002 and targeting another $1 billion in debt reduction for the following year. The company's declared objective was to have total debt in the range of 50% of total capital, allowing for temporary exceptions to enable strategic acquisitions such as the purchase of International Home 12 Con Agra Foods 903-412 Foods in 2001. In the future, the company expected to use available cash and cquity for organic growth, acquisitions, and product development. Into the Future Lxiling the Meal Business In September 2002, ConAgra completed the partial divestiture of its meat-processing businesses, a move Rhode described as reflecting ConAgra's "long-term strategic resolve to focus on branded and value-added food products." ConAgra sold its fresh beef, pork, and lamb businesses to Swift Foods Company, a recently created joint venture majority owned (54%) by equity investment firm Hicks, Muse, Tate & Turst and Booth Creek Investment Partners. In addition to a 46% equity share in Swill, valued at $150 million, ConAgra received about $766 million in cash and $440 million in credit and debt instruments. As part of the transaction, ConAgra purchased $150 million in senior subordinated notes from a subsidiary of Swift, effectively reducing the cash income from the sale. Swift Foods immediately joined the ranks of the major players as the second-largest cattle feeder, third-largest beef processor, and third-largest pork processor in the United States, as well as a leading lamb processor. Rohde emphasized that the new company would be a major supplier for ConAgra's processed meat products and that the shift from company-owned to company-sourced beef and pork represented "an important step in sharpening our strategic focus" toward value-added products. The transfer of the meat business released capital to be used in further debt reduction and the continued "the biggest signal that we are moving away from commodities. Il signaled thal enhancement of the value-added businesses, but more immediately, noted Rohde the move served as the company and outside the company." Investment analysts responded positively to the move, but with varying of enthusiasm. Several noted that while the sale of the meat business marked a major advance for the company, it was only a first step, given the company continued to retain significant commodity holdings. Still, the move highlighted ConAgra's resolve, and industry observers were predicting that the next step would be divestitures in the farm inputs segment, most likely through The sale of United Agri Products (UAP). inside degrees Next Steps As Rohde prepared for the next session with his management team, he kept reminding himself that "the deeper the culture, the harder it is to change." How could he further the momentum that had turned a successful commodity-oriented company into one that developed unique market leadership with innovative products such as Homestyle Bakes? How could he change the company's mind-set without destroying the commodity skills of those providing ingredients to the food system? In its cmerging role as a processed food company leader, ConAgra was more interested in responding to the nutritional and taste needs of an increasingly diverse group of customers. As he looked to the future, Rohde wondered what kinds of partnerships and relationships ConAgra should foster with leaders in food retailing, food service, biotech, and other key players in the food system. What additional divestitures and acquisitions should he consider in view of the new mission of the company? 13 903-412 Con Agra Foods Exhibit 1 ConAgra Stock Price, 1992 2002 540 535 $92 stock price hann 520 59 5-10 $5 $1 date Source Adapted by case writer freuen Thomson Financial Datastream, Exhibit 2 Comparative Stock Performance: 10-Year Cumulative Values Garaga Fardx - - RAP 50BP Packaged Fack Fond 3430 5420 5351 $390 5250 szava 5130 51 550 1992 1393 1994 1995 1995 1996 19 2000 2:01 SD 2002 1997 year Source: Adapled by casewriter from ConAgra Foods, Inc., September 26, 2002 Proxy Statement, PP. 19-21. available from I'rinurk, Global Access, , accessed October 7, 2002. Shows cumulative values based on a $100 investment made in May 1992, assuming reinvestment of dividends. Note: 14 903-412 -15- Exhibit 3a ConAgra Financials: Actual and Projected Income Statement (in millions of US$) 1999 2000 2001A 42% 28% 62% 21,541 21.40 . 35 * $ 5555 3 47 48% 999 * 20 2012 22 688.8 22 22 2009 2 2.500.3 26 59 23 BUD? $52 4813 59 4977 2007 5146 5221 5002 1928 $225 $2.51 $2.75 TA $3.51 Source: David 903-412 Con Agra Foods Exhibit 3b ConAgra financials: Actual and Projected Balance Sheet (in millions of USS) 1#? PA 23, 36&l= 8bij SHE & 122 127 128 #* 4 43 4 # # # g ? [ aa # | # ## 01 31 * = # #| # # R Exhibit 3c ConAgra Financials. Actual and Projected Cash Flow (in millions of USS) Adulto conde net income to ne Depreciation and per.will not Goodwill mortization 414 PrepadEpuree strom Being Operating de cs) 141) a sa 486/ 468) 1| taz ployee Ewy Fund stock purchases, net # % # # a g 2 a 3 its at and at your # # , Source: Nelson and Moskow, "Con Agra Foods, Inc." Credit Suisse Fquity Research, September 23, 2002, pp. 1011. 16 903-412 -17- Exhibit 4 Major Food and Agribusiness Companies. Stock Market Valuations Market Cap ($ mil) YTD% Change Company Share Price $ Est. 5-yr Growth 2002E EPS 2003L EPS 2002E P/E 2003E P/E % Yield -26.1 4.5 Major Packaged Food Campbell ConAgra General Mills Heinz Hershey Kellogg Kraft McCormick Sara Lee Wm. Wrigley 9,075 13, 183 16,702 11,797 8,563 13,719 63,367 3,255 14,961 11,133 22.08 24.85 44.42 33.37 62.05 33.25 36.46 22.80 18.29 49.49 -14.6 -18.8 -8.3 10.5 7.1 8.6 -17.7 -3.7 1.37 1.55 2.23 2.46 3.17 1.73 2.04 1.31 1.42 1.78 1.55 1.69 2.89 2.63 3.50 1.90 2.30 1.43 1.55 8 7 11 9 9 10 10 13 10 16.1 16.0 19.9 13.6 19.6 192 17.9 17.4 12.9 27.8 14.2 14.7 15.4 12.7 17.7 17.5 15.9 15.9 11.8 25.3 2.9 40 2.5 3.2 2.1 3.0 1.6 1.8 3.3 1.7 8 1.96 12 1.00 8,075 2,143 Agribusiness ADM Bunge CPI Smithfield Tyson -8.5 9.1 -18.4 -28.8 0.7 28.75 0.78 2.25 1.85 1.29 1.08 10 10 12 9 9 9 2.50 2.25 1.32 1.19 16.0 10.8 17.4 12.2 10.8 1.6 1.6 1.4 12.5 9.7 12.8 11.9 9.8 1,987 4.327 15.70 11.63 1.4 International Danone Nestle Unilever NV Unilever PLC 24.06 53.75 59.45 36.45 1.08 2.85 3.71 1.16 3.22 4.08 8 8 10 10 10 22.3 18.9 16.0 16.4 20.7 16.7 14.6 14.9 1.1 15 1.7 2.22 2.44 2.3 Source: Adapted by casewriter from John M. McMillin, et al. "Food/Agribusiness: October-November 2002 Monthly," Prudential Financial Researc, pp. 416, available from The Investext Group, , accessed Oxtober 14, 2002. Note: Share prices were as of market dosing on September 30, 2002. EPS and P/E estimates were for the calendar year. 903-12 Con Agora Foods Exhibit 5 ConAgra Food's Major Brands Megabrands Leading Brands Regional and Niche Brands Healthy Choice Banquet Butterball Chef Boyardee Eckrich Hunt's Snack Pack Orville Redenbacher Fleischman's Blue Bonnet Swiss Miss Kid Cuisine Hebrew National Pam's Wesson Armour Ro'Tel Parkay Guiden's Patio Act II Marie Callender's Van Camp's Reddi-wip Louis Kemp Egg Beater's Brown n' Serve Bumble Bee Manwich Treasure Cave Wolf Brand Rosarita Knott's Berry Farm Luck's Beanee Weenee 903-412 ConAgra Foods Exhibit 8 ConAyra Foods Divisional Indicators, 1997-2004E ConAgra, Inc. Divisional Results, 1997-03E (May Fiscal Year) 888 a - 3 5954 0 ORO NOON Source: Willian Leach, "Cunga Tuods, Inc., "Banc of Ancrica Securities, September 19, 2002, p. 2. Note: fiscal year mids May. EPS after 2002 exclude 50.15 in goodwill churpes Con Agra Foods 903-412 Exhibit 9 New and Old Financial Reporting Segments New Reporting Segments Old Reporting Segments Packaged Foods Same as old reporting segments, but now including branded processed meats (formerly included under the now discontinued Refrigerated Foods segment). Packaged Foods Branded and value-added shelf-stable, frozen, and refrigerated products for retail and food-service customers. Food Ingredients Processed seasonings, blends, and flavorings Processed grains Refrigerated Foods Branded processed meats (deli, hot dogs, sausages) Fresh beef and pork Fresh poultry Meat Processing Fresh beef and pork Fresh poultry Agricultural Products Crop inputs distribution (United Agri Products) Commodity trade and merchandising (grains, energy) Agricultural Products Crop inputs distribution (United Agri Products) Commodity trade and merchandising (grains, energy) Food ingredients (processed grains & spices) Source: Company document, Note: New financial reporting woments went into effect in December 2001 Exhibit 10 Net Sales and Operating Profit Distribution by New Reporting Segments As % of Total: : 2004 2003E 2002 2001 2000 Packaged Foods Net sales Op profit 63.5% 83.1 57.7% 82.4 44.8% 78.2 42.0% 75.1 40.0% 80.6 Food Ingredients Net sales Op profit 87 8.2 7.9 8.1 6.0 7.8 6.1 9.3 6.7 7.2 Meat Processing Net sales Op profit 10.1 3.6 18.0 6.1 36.3 13.1 38.5 9.7 40.2 8.3 Agricultural Products Net sales Op profit 17.8 5.1 16.5 3.3 12.9 0.9 13.4 5.9 13.1 3.9 Total value Net sales (Smil) Op profit (Smil) 20,867 2,203 22,090 2,092 27.630 2.058 27.101 1,859 25,485 1,239 Source: Adapted from William Leach, "CanAgra Foods, Inc.," Banc of America Securities, September 19, 2002, p.2. Operating profit was before interest experise, goodwill annuntiation, petieral aurpurate expenses, and income taxes Note: 21 903-412 ConAgra Foods Rohde placed the pace of industry consolidation at the top of the list of challenges for the company. Customers in both retail and food services were highly consolidated, and ConAgra's competitors were following suit. ConAgra itself was the product of decades of acquisitions, the most recent major deal being the S2.9 billion purchase of International Home Foods in 2000, which added several popular brands to ConAgra's portfolio. But until recently, ConAgra's growth had not been combined with an effective consolidation strategy, and Rohde realized that the company was out of synch with its customer base. "From the client's perspective, ConAgra was too cumbersome and difficult to do business with," he said. Correcting this situation became a company priority. Biotechnology The dramatic worldwide growth in farming productivity since the 1960s was made possible by improved fertilization, crop management, and especially the development of scientifically enhanced seeds. The crossbreeding techniques originally used to improve crops were later replaced by genetic engineering of seeds, a process known as bioengineering, or biotechnology. Agricultural biolech- nology was primarily used to develop insect- and disease-resistant crops. One of the most successful innovations had been Monsanto Company's Roundup Ready variety of corn and soybeans. These " crops were resistant to Monsanto's top-selling herbicide, making it easier for farmers to keep their fields free of weeds with less need for chemicals and filling Products developed through genetic engineering by other companies included crops resistant to pests, cold, and drought; fruits and vegetables with longer shelf lives; and pigs with reduced fai content. Also on the horizon were nutritionally enhanced consumer products such as proteins fortified with beneficial Omega-3 (ally acids. Biotechnology advocates argued that genetic engineering held the solution to effectively feeding the world's ever-expanding population. Genetically engineered crops could also benefit the environment by limiling the acreage needed for planling, thereby preventing deforestation and soil erosion Opponents expressed concern that pest-resistant crops could lead to the development of "super insects" capable of resisting both new and conventional controls. Vocal opposition also came from consumer groups, especially in Europe, that feared laboratory tampering with foods. Consumer suspicion of genetically modified foods threatened to slow the advent of new products or relegate them to nonhuman consumption, in animal feeds for example. Increasingly, however, the public was realizing that biotechnology was not just genetically modified organisms (GMOs) but rather a method for improving the quality and nutritionally sound use of food. ConAgra had just begun exploring the role of biotechnology in the company's future. Rohde was convinced that biotechnology could not only reduce environmental damage but also lead to important nutritional breakthroughs that would benefit consumers. Ultimately, he knew, it would be up to the consumers to decide biotechnology's role in the food business: If customers demanded biotech products, ConAgra would provide them. Slock Valuations U.S. food stocks hit an all-time high in 1997, when shares in food-processing companies were trading at a 30% premium to the overall stock market. The high valuation of food stocks was due largely to earnings growth from expanding international markets, so when the Asian currency crisis hit in 1998, food price-to-carnings (P/E) ratios dropped markedly. Food stocks showed signs of recovery beginning in 2000, as a weakened U.S. economy and plummeting technology stocks sent investors running to traditional business sectors, but the overall trend continued downward. (See Figures B and C.) Nevertheless, since the peak of the technology bubble in March 2000, the Standard Con Agra Foods 903-412 & Poor's (S&P) food index had risen 30.6%, while the S&P 500 declined 40.4%. During the first half of 2002, food stocks outperformed the S&P 500 by 15.6 percentage points. 18 Figure B Food Stocks P/E Ratios / Figure C Comparative P/E Ratios 33 Total U.S. U.S. Food Processors 28 Total World Market World Food Processors Year Market 23 1997 30.5 23.4 23.6 21.0 1998 26.1 27.7 23.3 24.8 18 1999 22.7 30.8 20.6 30.5 13 2000 23.4 25.3 22.1 23.4 2001 21.9 27.8 19.5 22.3 8 Sep. 2002 20.9 22.7 17.5 18.6 3 1953 1963 1973 1983 1993 2003E Source: Ranc of America Securities, Equity Research.19 Source: Thomson Financial Datastream. Wall Street generally grouped food companies into two major categories: agribusiness companies engaging in early- to middle-stage processing such as milling and meatpacking and middle- to late- stage processors, known as food manufacturers or food packagers, that sold finished products to retailers, restaurants, and other institutions. This distinction was important to the large food companies because most were publicly traded firms, and market performance and financial results were judged by stock analysts who used these categories to establish benchmarks for comparison with competitor firms. Compared with packaged food companies, commodity-oriented companies tended to have significantly lower net profit margins, higher earnings volatility, and consequently, lower P/E ratios. For example, Credit Suisse First Boston forecast 2002 average P/E ratios at 11.1 for the commodity foods group and 18.6 for packaged food companies. The valuation for ConAgra, with its mixed portfolio of commodity and packaged food assets, fell in between, with a forward P/E of 15.5.20 For 2003, Merrill Lynch was predicting that ConAgra stock would trade at a 16% premium lo the commodity-food index and at a 7% discount to the processed-food index 21 (See Exhibit 4 for comparative financial indicators of major food companies.) a 18 G. Leonard leitelbaum, "The Food Industry," Merrill Lynch Research (In-depth Report), PP. 2-5, available from The Investext Group accessed October 14, 2002 20 David C. Nelson and Robert B. Moskow, "Food for Thought: Food & Agribusiness Weekly," Credit Suisse Equity Research, September 9, 2012, p. 2, available from The Investext Grenap, , accessed September 30, 2002. 21 Calculated from Merrill Lynch forecast P/E ratlos presented in Teitelbaum, "The Food Industry," p. 59. 9 903-412 ConAgra Foods ConAgra held perhaps the most diversified position or any food company in the world, in that it operated at both ends of the food supply chain, from farm inputs to retail and food service. (In fact, ConAgra held the distinction of being counted within the packaged foods group at Credit Suisse, while at the same time being included in Merrill Lynch's commodity index.) In the past, ConAgra had often heralded its "farm gate to dinner plate" character as a unique advantage to the company, providing increased opportunities for synergies and easing cyclical effects at either end of the business. More recently, however, the company was finding that ils unparalleled position in the industry was also a source of confusion for Wall Street, potential investors, and even its own employees as they tried to assess ConAgra's performance and future prospects. Introducing the New ConAgra Foods ConAgra had taken steps to promote teamwork and, through Operation Overdrive, was changing the structure of its internal operations, but the message that the old ConAgra was history had yet lo hit home-both inside and outside the company. Rohde was also concerned about ConAgra's persistent image as an agricultural conglomerate. A ConAgra executive in investor relations recalled that when he joined the company in 2000, "ConAgra carried the baggage of a commodity company image." Though by then the company had gone from just 16 brands in 1996 to 27 brands with annual retail sales of over $100 million each, investors were still more likely to compare Con gra with Cargill than with Krall. By 2002 ConAgra's portfelowhaide world struggling to understand the nature over 35 , of which are listed in Exhibit 5.) It was not just the outside of the company. ConAgra was going through an identity crisis, evidenced in the pages of its annual reports. The 1998 report described the company as operating "across the food chain," providing "products and services from farm gate to dinner plate." By 2000 the company had transformed into "the home of great brands and great taste, North America's largest foodservice supplier, and a strong basic foods business." Driving the message home was the annual report's front cover carrying the one-word question: "Hungry?" Directly below came the answer in the form of the company's new name: "ConAgra Foods." As the company assessed its opportunities in fiscal years 2000 and 2001, management knew that significant changes encompassing cultural , functional, and marketplace resources would be necessary to position the company io provide shareholders with strong uiure relurns. These changes, which the company described as "a transformation from an agribusiness giant to America's favorite food company," involved four major arcas: portfolio of businesses held by the company; sales and marketing excellence; infrastructure development, specifically with logistics and Mis; and resource deployment Becoming America's Favorite Food Company In 2000, ConAgra Inc. changed its name to ConAgra Foods, a move that drew little public notice since, after all, ConAgra was hardly a household name. Despite the prevalence of ConAgra products in kitchen cabinets across the country, few people knew "the good name behind the good names." A ConAgra Foods brand marketing campaign launched in 2001 set out to change that. Through print advertising, media spots, and the placing of the ConAgra Foods logo as a "trust mark" on all of its products, consumers would soon know the name of the company that made many of their favorite brands. (See Exhibits 6 and 7.) The ConAgra logo also appeared for the first time on subsidiary letterhead and business cards, delivering the image of ConAgra Foods as a single unified company internally and to everyone the company did business with. 10 ConAgra loods 903-412 Rohde led the drive for change with a newly articulated common vision for the company to become "America's Favorite Food Company." For Rohde, this was not a slogan or a claim but a goal for all ConAgrans to strive for. Rohde explained that the phrase was deliberately ambiguous: What it means to be America's favorite food company can mean different things different people. "America" can mean just the United States, or extend to all of North America, since ConAgra also does business in Canada and Mexico. America can also include South America, where ConAgra may be operating in the future. America does not preclude global expansion, because the term could refer to ConAgra's being an American-based company or to its selling American food Rohde wanted a message that allowed for multiple visions of the company's future, potentially encompassing all aspects of existing operations. By not establishing a fixed destination or end point, the mission of becoming America's favorite food company allowed the company's goals to evolve along with the changing industry. Carning Trust and Building Reputation Rohde understood that to become America's favorite food company, ConAgra Foods had to stand for something in the public mind. The ability to attract consumers, investors, and the best employees would ultimately depend on the company's performance and reputation. The company had to prove that willing to go the extra mile to earn the public's trust respect. Corporate governance in the course of the 2002 fiscal year, ConAgra authored and distributed a new code of conduct document for the company and formalized and strengthened several long-standing practices. Taking a position beyond what was legally required, ConAgra stipulated that company directors and executive officers not sell their shares in ConAgra Foods until at least six months after leaving the company. At the same time, ConAgra amended its 401(k) plans so that employees could select investment alternatives for their vested funds. Commitment to food safety Recognizing that "it's all about our products," ConAgra established the Office of Product Quality and Development to implement the industry's highest standards of food safety. ConAgra's handling in the summer of 2002 of what was then the second- largest meat recall in history further signaled the company's uncompromised commitment to food safely. By taking safety measures beyond those required by the government, ConAgra assumed a position of leadership on an important industry issue. On June 30, 2002, ConAgra recalled 354,200 , pounds of ground beef following the detection of E. coli bacteria in samples taken from meat processed at its Greenly, Colorado plant. Twenty days later ConAgra voluntarily expanded the recall to 18.6 million pounds. ConAgra received praise for voluntarily expanding the recall at great company expense. This same action, however, angered many of ConAgra's that the expanded recall was not mandated because the government did not have scientific data competitors, who argued showing that the meat was bad. "That's right," responded Rohde. "The government's not recalling it-we arc, out of an abundance of caution for our consumers and to further the education and awareness of society." For many observers, thal ConAgra was able to consummate the sale of its meal business in September 2002 demonstrated the level of trust and respect the ConAgra name had attained within the food industry and among consumers a 11 903 412 Con Agra Foods Focus and Simplicity Because of all the acquisitions that had taken place over the past several years, it was difficult to define the company to outside investors and to company managers. (Exhibit 8 is only one indication of the vast array of individual companies and the mixture of brand and commodity products that make up ConAgra.) The performance varied from a loss of $20 million in United Agri Products in fiscal 2002 to a profit of $500 million in Hunt Wesson in the same year. Managing this complex system with a primary concern on meeting financial targets had forced managers to focus on individual business units and short-term profit goals rather than on positioning ConAgra as a lood company for the future Redefined business segments Con gra's reporting segments had long been defined in a way that made sense to the company in terms of temperature states and logistical planning but that did not always make sense to the outside world. In December 2001, ConAgra announced that it had reorganized its financial reporting segments to better represent the nature of its business. (See Exhibit 9.) Rohde explained the reasoning behind the change: We sorted out the financial reporting segments so people could understand us better. We had been criticized for not being transparent, and we weren't. We had some packaged meat products under refrigerated foods (along with fresh meats), even though they were shelf stable and should have been in with the packaged foods. This drove analysts crazy because it obscured what was going on in the meat business. The newly defined segments achieved greater transparency and also made it easier to distinguish the value-added from the commodities-oriented businesses. The old reporting segments had mixed food with nonfood businesses and value-added products with commodities. Under the new reporting method, the meal-processing segment was limited to commodity foods, and the agricultural products segment was redefined to contain only nonfood businesses (including grain merchandising). (Exhibit 10 shows the distribution of sales and profits by the new segments.) Connecting with the consumer The new ConAgra was to be consumer driven, meaning that the company would focus on creating consumer demand through innovative products and creative marketing. In the past, a focus on certain performance goals had led the company to lose touch with its customers and to forget that, ultimately, it was the consumers' needs that had to be met. The goal was to put yourself in your customer's shoes, explained Tim McMahon, ConAgra's head of marketing and communications: "I am in my customer's business. If I can meet the demands of the consumer, then I serve my customer." By focusing on the consumer, ConAgra could increase sales and benefit all of ils constituents: consumers, customers, employees, and shareholders. The new approach recognized that ConAgra supplied its retail and food-service customers with more than products-ConAgra was idcally positioned to provide knowledge and information about the way America eats. Financial resource discipline Since the late 1990s, ConAgra had modified its financial goals from a strict focus on earnings per share and return on equity standards to an emphasis on metrics that reflected the overall health of the business, such as sales growth, margin expansion, earnings growth, and return on invested capital. Becoming America's favorite food company would also require effective and efficient use of financial resources. To that end, in 2002 ConAgra eliminated its former dependence on short-term debl by converting $2 billion to long-term debt at attractive interest rates. ConAgra also directed its free cash flow toward overall debt reduction, reducing debt by $1.2 billion in fiscal 2002 and targeting another $1 billion in debt reduction for the following year. The company's declared objective was to have total debt in the range of 50% of total capital, allowing for temporary exceptions to enable strategic acquisitions such as the purchase of International Home 12 Con Agra Foods 903-412 Foods in 2001. In the future, the company expected to use available cash and cquity for organic growth, acquisitions, and product development. Into the Future Lxiling the Meal Business In September 2002, ConAgra completed the partial divestiture of its meat-processing businesses, a move Rhode described as reflecting ConAgra's "long-term strategic resolve to focus on branded and value-added food products." ConAgra sold its fresh beef, pork, and lamb businesses to Swift Foods Company, a recently created joint venture majority owned (54%) by equity investment firm Hicks, Muse, Tate & Turst and Booth Creek Investment Partners. In addition to a 46% equity share in Swill, valued at $150 million, ConAgra received about $766 million in cash and $440 million in credit and debt instruments. As part of the transaction, ConAgra purchased $150 million in senior subordinated notes from a subsidiary of Swift, effectively reducing the cash income from the sale. Swift Foods immediately joined the ranks of the major players as the second-largest cattle feeder, third-largest beef processor, and third-largest pork processor in the United States, as well as a leading lamb processor. Rohde emphasized that the new company would be a major supplier for ConAgra's processed meat products and that the shift from company-owned to company-sourced beef and pork represented "an important step in sharpening our strategic focus" toward value-added products. The transfer of the meat business released capital to be used in further debt reduction and the continued "the biggest signal that we are moving away from commodities. Il signaled thal enhancement of the value-added businesses, but more immediately, noted Rohde the move served as the company and outside the company." Investment analysts responded positively to the move, but with varying of enthusiasm. Several noted that while the sale of the meat business marked a major advance for the company, it was only a first step, given the company continued to retain significant commodity holdings. Still, the move highlighted ConAgra's resolve, and industry observers were predicting that the next step would be divestitures in the farm inputs segment, most likely through The sale of United Agri Products (UAP). inside degrees Next Steps As Rohde prepared for the next session with his management team, he kept reminding himself that "the deeper the culture, the harder it is to change." How could he further the momentum that had turned a successful commodity-oriented company into one that developed unique market leadership with innovative products such as Homestyle Bakes? How could he change the company's mind-set without destroying the commodity skills of those providing ingredients to the food system? In its cmerging role as a processed food company leader, ConAgra was more interested in responding to the nutritional and taste needs of an increasingly diverse group of customers. As he looked to the future, Rohde wondered what kinds of partnerships and relationships ConAgra should foster with leaders in food retailing, food service, biotech, and other key players in the food system. What additional divestitures and acquisitions should he consider in view of the new mission of the company? 13 903-412 Con Agra Foods Exhibit 1 ConAgra Stock Price, 1992 2002 540 535 $92 stock price hann 520 59 5-10 $5 $1 date Source Adapted by case writer freuen Thomson Financial Datastream, Exhibit 2 Comparative Stock Performance: 10-Year Cumulative Values Garaga Fardx - - RAP 50BP Packaged Fack Fond 3430 5420 5351 $390 5250 szava 5130 51 550 1992 1393 1994 1995 1995 1996 19 2000 2:01 SD 2002 1997 year Source: Adapled by casewriter from ConAgra Foods, Inc., September 26, 2002 Proxy Statement, PP. 19-21. available from I'rinurk, Global Access, , accessed October 7, 2002. Shows cumulative values based on a $100 investment made in May 1992, assuming reinvestment of dividends. Note: 14 903-412 -15- Exhibit 3a ConAgra Financials: Actual and Projected Income Statement (in millions of US$) 1999 2000 2001A 42% 28% 62% 21,541 21.40 . 35 * $ 5555 3 47 48% 999 * 20 2012 22 688.8 22 22 2009 2 2.500.3 26 59 23 BUD? $52 4813 59 4977 2007 5146 5221 5002 1928 $225 $2.51 $2.75 TA $3.51 Source: David 903-412 Con Agra Foods Exhibit 3b ConAgra financials: Actual and Projected Balance Sheet (in millions of USS) 1#? PA 23, 36&l= 8bij SHE & 122 127 128 #* 4 43 4 # # # g ? [ aa # | # ## 01 31 * = # #| # # R Exhibit 3c ConAgra Financials. Actual and Projected Cash Flow (in millions of USS) Adulto conde net income to ne Depreciation and per.will not Goodwill mortization 414 PrepadEpuree strom Being Operating de cs) 141) a sa 486/ 468) 1| taz ployee Ewy Fund stock purchases, net # % # # a g 2 a 3 its at and at your # # , Source: Nelson and Moskow, "Con Agra Foods, Inc." Credit Suisse Fquity Research, September 23, 2002, pp. 1011. 16 903-412 -17- Exhibit 4 Major Food and Agribusiness Companies. Stock Market Valuations Market Cap ($ mil) YTD% Change Company Share Price $ Est. 5-yr Growth 2002E EPS 2003L EPS 2002E P/E 2003E P/E % Yield -26.1 4.5 Major Packaged Food Campbell ConAgra General Mills Heinz Hershey Kellogg Kraft McCormick Sara Lee Wm. Wrigley 9,075 13, 183 16,702 11,797 8,563 13,719 63,367 3,255 14,961 11,133 22.08 24.85 44.42 33.37 62.05 33.25 36.46 22.80 18.29 49.49 -14.6 -18.8 -8.3 10.5 7.1 8.6 -17.7 -3.7 1.37 1.55 2.23 2.46 3.17 1.73 2.04 1.31 1.42 1.78 1.55 1.69 2.89 2.63 3.50 1.90 2.30 1.43 1.55 8 7 11 9 9 10 10 13 10 16.1 16.0 19.9 13.6 19.6 192 17.9 17.4 12.9 27.8 14.2 14.7 15.4 12.7 17.7 17.5 15.9 15.9 11.8 25.3 2.9 40 2.5 3.2 2.1 3.0 1.6 1.8 3.3 1.7 8 1.96 12 1.00 8,075 2,143 Agribusiness ADM Bunge CPI Smithfield Tyson -8.5 9.1 -18.4 -28.8 0.7 28.75 0.78 2.25 1.85 1.29 1.08 10 10 12 9 9 9 2.50 2.25 1.32 1.19 16.0 10.8 17.4 12.2 10.8 1.6 1.6 1.4 12.5 9.7 12.8 11.9 9.8 1,987 4.327 15.70 11.63 1.4 International Danone Nestle Unilever NV Unilever PLC 24.06 53.75 59.45 36.45 1.08 2.85 3.71 1.16 3.22 4.08 8 8 10 10 10 22.3 18.9 16.0 16.4 20.7 16.7 14.6 14.9 1.1 15 1.7 2.22 2.44 2.3 Source: Adapted by casewriter from John M. McMillin, et al. "Food/Agribusiness: October-November 2002 Monthly," Prudential Financial Researc, pp. 416, available from The Investext Group, , accessed Oxtober 14, 2002. Note: Share prices were as of market dosing on September 30, 2002. EPS and P/E estimates were for the calendar year. 903-12 Con Agora Foods Exhibit 5 ConAgra Food's Major Brands Megabrands Leading Brands Regional and Niche Brands Healthy Choice Banquet Butterball Chef Boyardee Eckrich Hunt's Snack Pack Orville Redenbacher Fleischman's Blue Bonnet Swiss Miss Kid Cuisine Hebrew National Pam's Wesson Armour Ro'Tel Parkay Guiden's Patio Act II Marie Callender's Van Camp's Reddi-wip Louis Kemp Egg Beater's Brown n' Serve Bumble Bee Manwich Treasure Cave Wolf Brand Rosarita Knott's Berry Farm Luck's Beanee Weenee 903-412 ConAgra Foods Exhibit 8 ConAyra Foods Divisional Indicators, 1997-2004E ConAgra, Inc. Divisional Results, 1997-03E (May Fiscal Year) 888 a - 3 5954 0 ORO NOON Source: Willian Leach, "Cunga Tuods, Inc., "Banc of Ancrica Securities, September 19, 2002, p. 2. Note: fiscal year mids May. EPS after 2002 exclude 50.15 in goodwill churpes Con Agra Foods 903-412 Exhibit 9 New and Old Financial Reporting Segments New Reporting Segments Old Reporting Segments Packaged Foods Same as old reporting segments, but now including branded processed meats (formerly included under the now discontinued Refrigerated Foods segment). Packaged Foods Branded and value-added shelf-stable, frozen, and refrigerated products for retail and food-service customers. Food Ingredients Processed seasonings, blends, and flavorings Processed grains Refrigerated Foods Branded processed meats (deli, hot dogs, sausages) Fresh beef and pork Fresh poultry Meat Processing Fresh beef and pork Fresh poultry Agricultural Products Crop inputs distribution (United Agri Products) Commodity trade and merchandising (grains, energy) Agricultural Products Crop inputs distribution (United Agri Products) Commodity trade and merchandising (grains, energy) Food ingredients (processed grains & spices) Source: Company document, Note: New financial reporting woments went into effect in December 2001 Exhibit 10 Net Sales and Operating Profit Distribution by New Reporting Segments As % of Total: : 2004 2003E 2002 2001 2000 Packaged Foods Net sales Op profit 63.5% 83.1 57.7% 82.4 44.8% 78.2 42.0% 75.1 40.0% 80.6 Food Ingredients Net sales Op profit 87 8.2 7.9 8.1 6.0 7.8 6.1 9.3 6.7 7.2 Meat Processing Net sales Op profit 10.1 3.6 18.0 6.1 36.3 13.1 38.5 9.7 40.2 8.3 Agricultural Products Net sales Op profit 17.8 5.1 16.5 3.3 12.9 0.9 13.4 5.9 13.1 3.9 Total value Net sales (Smil) Op profit (Smil) 20,867 2,203 22,090 2,092 27.630 2.058 27.101 1,859 25,485 1,239 Source: Adapted from William Leach, "CanAgra Foods, Inc.," Banc of America Securities, September 19, 2002, p.2. Operating profit was before interest experise, goodwill annuntiation, petieral aurpurate expenses, and income taxes Note: 21