Question: I need help with my ITMA class, we were told to summarise the article below in no more than 500 words. If someone can write

I need help with my ITMA class, we were told to summarise the article below in no more than 500 words. If someone can write it out for me, while starting it with an intro then the summary and a conclusion (3 paragraphs), that would be appreciated.

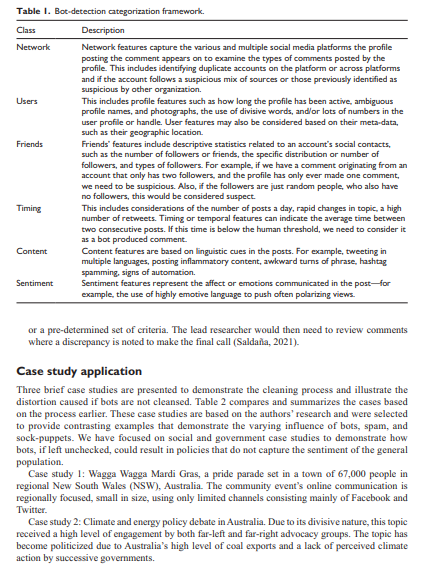

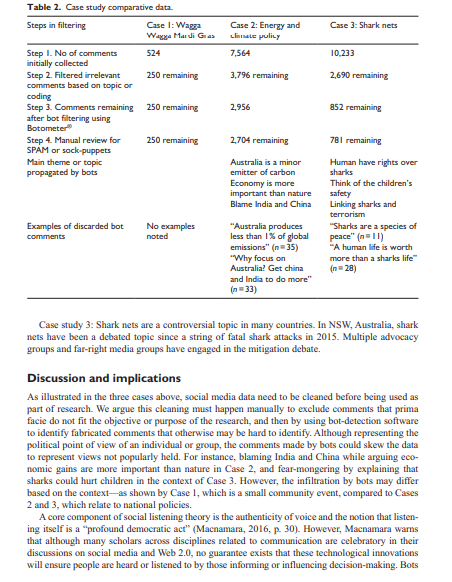

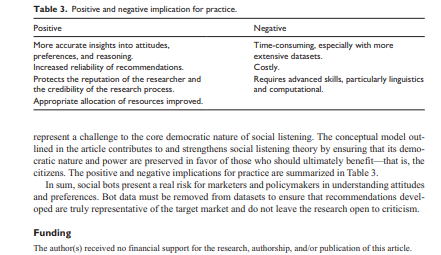

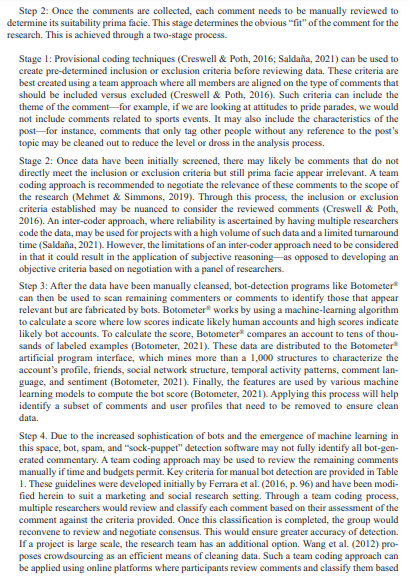

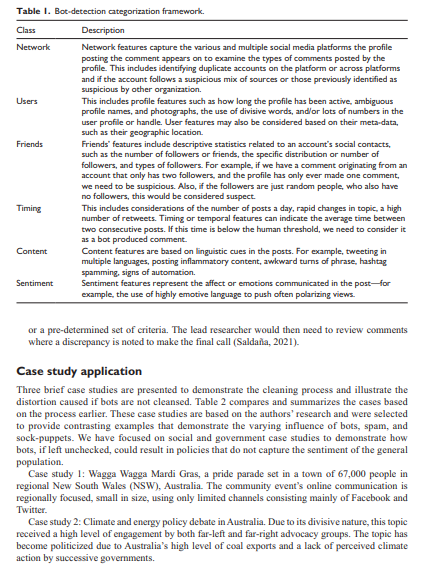

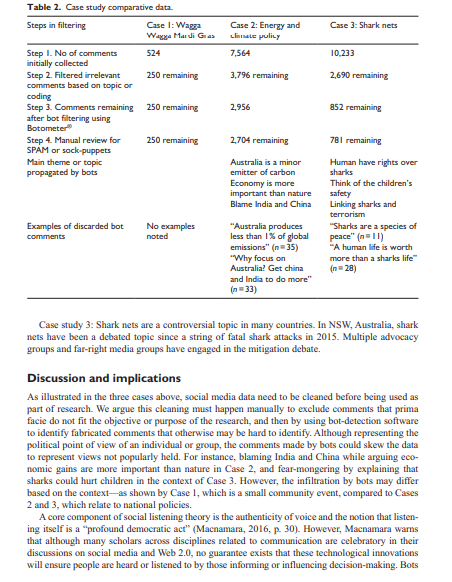

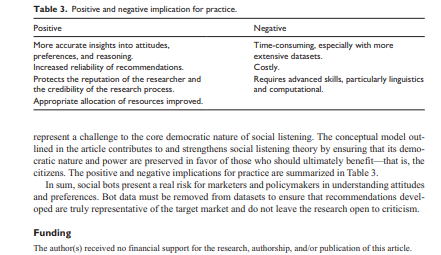

International Journal of Market Research Research Note Lots of bots or maybe nots: A process for detecting bots in social media research International journal of Market Research 2021, Vol. 625) 552-559 The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines gepub.com/journals permissions DOE 10.1177/14707853211027486 journals.sagepub.com/home/mre SSAGE Michael Mehmet University of Wollongong. Australia Kane Callaghan and Clifford Lewis Charles Sturt University, Australia Abstract The use of bot messaging that being artificially created messages, has increased since 2010. While not all bots are bad, many have been used to share extreme and divisive views on a range of topics, from policy discussion to brand electronic word of mouth. The issue with bot messaging and its prevalence is that it can affect researchers' understanding of a topic. For example, if 25% of a dataset is fabricated decision-making may result in a loss of profit or poor policy formation. To counteract the use of bots, this research note offers a framework to alleviate the potentially destructive nature of bot data and ensure the cleaning of data is thorough and beneficial to decision-making based on social media commentary. The framework is a four-step process, which includes thematic, automated, and characteristic identification stages. We provide three case studies to demonstrate the approach and conclude by providing key practical implications. Keywords bots, cleaning, filtering, sentiment, social media Introduction Social media data have become an alluring source of insight into the mindsets of the general popu- lation by providing a relatively cheap, quick, and easy-to-access source of data (Graham et al., 2020). These benefits align with shrinking corporate and academic budgets and time pressures to turnaround projects, particularly exacerbated by COVID-19. However, this perceived panacea comes with risks (Kozinets, 2019), which, if not addressed appropriately, can contaminate results and findings (Saldaia, 2021) making it almost impossible to provide accurate, evidence-based conclusions and recommendations. This research note will provide a framework to assist in over- coming a key issue, that being bot messaging contaminating social media data. Netnography guru Kozinets (2019) strongly advocates filtering as a vital step in ensuring the authenticity and usability of online sourced community and consumer data. Such filtering may happen at two levels-first at a thematic level, to exclude comments that do not fit the research- er's criteria, and second, to exclude those that prima facie appear authentic but may be fabricated. Recent studies (Crabb et al., 2015; Freelon et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2020) have highlighted the concern of highly organized online activists who can influence and contaminate data with the use of bots (automated content creation tools), spam (mass communication messaging), and "sock- puppets" (a fake account designed to distort and manipulate public opinion). Despite acknowl- edging the challenges in using social media data, few studies have explored this process and how it may be applied effectively in practice (Graham et al., 2020). This article, therefore, provides a structured approach that industry and academic researchers can apply when using social media data. Social media research typically involves analyzing comments made in response to posts that discuss a relevant topic or present an idea of interest to the researcher (Liu, 2010). The data col- lected can provide insight into consumers' responses to various topics, from brands to government policy (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). For brands, it can provide rapid insights on new marketing programs, helping the brand assess and correct campaigns efficiently (Snchez-Nuez et al., 2020). Similarly, governments may use social media commentary to understand their constituents' needs and their response to new policies (Hubert et al., 2020). By understanding these responses, policy- makers can gain clear insights into peoples' attitudes and preferences (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019), enabling govemments to amend policies or implement additional communication campaigns or interventions to enhance compliance. In the context of social marketing, Hubert et al. (2020) explain that social listening is an essential component to designing interventions that have a social impact. Dobson (2014) similarly argues that centralizing "listening at or near the heart of the demo- cratic process leads us in the direction of dialogie democracy" (p. 6). Consistent in Mehmet and Simmons (2019) and Dobson (2014) is the need for policymakers to engage and seek feedback from those affected by the policies developed. Such feedback helps ensure policies align with the nuances of those being affected by them-thus, helping to ensure greater compliance and better implementation outcomes (French & Gordon, 2019). Social media can play a role in assisting to expedite the feedback process. To use social media data effectively, it is essential to address data appropriateness (Kozinets, 2019). A problem, however, lies in assessing data that looks like a natural response but is fabricated by software robots (bots), which are algorithms designed to engage in human-like conversations (Bollen et al., 2011; Ferrara et al., 2016). Bots have been skewing social media discussions for nearly a decade (Wiesenberg & Tench, 2020). These bots have fake names, biographies, and pho- tographs, and newer bots have even evolved to have personalitiesmaking it difficult to distin- guish the language they use from other authentic posts. Bots can skew social discourse by suggesting, reinforcing, and conflating views that the major- ity may not hold-and, in doing so, silence opposing debates by making them appear as a minority (Ferrara, 2020; Graham et al., 2020). This "filter bubble" effect (Pariser, 2011) creates a curated content echo chamber of public opinion (Bozdag & van den Hoven, 2015). For marketers or poli- cymakers attempting to influence brand or policy, bots can infiltrate discourse (Schneier, 2020), spread misinformation, and skew the insights developed (Daniel et al., 2019; Reuter & Lee, 2019). To illustrate their significance, reports indicate bots published nearly one-fifth of all tweets about the 2016 US presidential election, and according to one estimate, about one-third of all tweets about that year's Brexit vote (Ferrara, 2020). This highlights the need to screen posts when using them as part of the research process to ensure credibility (Ferrara, 2020; Ferrara et al., 2016) and validity (Reuter & Lee, 2019). We acknowledge that not all bots are bad or designed to be nefarious, and some may be created by authorized accounts like government agencies to inform the population (Allem et al., 2017; Ledford, 2020). However, this article focuses on bots that pose as average consumers with the intent of misleading or skewing commentary on social media. We put forward an approach that may be used to enhance the quality of social media research by implementing a data cleaning and bot-detection process. Importantly, this study focuses on the process of cleansing, rather than advo- cating for particular bot-detection programs or services, of which there are many in the market- place. The reason for this is twofold, first, the literature extensively examines the effectiveness of bot-detection software, and second, despite acknowledging the effectiveness of such software, lit- tle has been written on incorporating bot detection into current research processes and designs (see Cai et al., 2017, Hui et al., 2019; Kudugunta & Ferrara, 2018; Yang et al., 2020). This article pre- sents a process that can be followed, and then illustrates the process with brief case studies designed to highlight the implications in practice. Data cleaning and bot-detection approach Social listening procedures typically follow a set of steps associated with traditional research meth- ods, which include establishing aims, defining scope, collecting data, filtering and cleaning the data, coding and analysis, and reporting (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). There are two potential approaches when incorporating bot-detection stages in the cleaning processes. The first approach includes using an automated bot-detection tool, which filters potential bot data before the researcher sees the raw data (Hui et al., 2019). A manual process in then used to filter data based on relevance to the research aims and inclusion or exclusion protocols (Saldaila, 2021). The advantage of this approach is speed; however, one major downfall is not being exposed to bot-created content, which has been shown to affect online sentiment and opinion (Graham et al., 2020). Hence, we propose an alternative approach wherein bot detection is applied after an initial review of the raw data. The advantage of this approach is that it allows the researcher to identify bot-created comments and interpret them in context. Furthermore, it assists in understanding how the bot-created comments have potentially affected or biased other participants' views of the world, the type of commentary they share, and the topic of discussion more broadly. This approach is now discussed considering the stages of data collection and filtering when using social media as a source of data. Step 1. Software like Facepage or exporteomments provides a platform where researchers can export comments relating to specific social media postsfor instance, a news article that discusses a policy or an advertisement or information post. Typically, these platforms allow the researcher to export comments in comma-separated values (CSV) format. Kozinets (2019) cautions that researchers must immerse themselves in the research area to ensure a higher likelihood of quality data. This immersion includes identifying posts that can be used as sources for comments. In some instances, these sources could be very narrow-for example, if a marketer was trying to establish how consumers respond to a specific advertisement, they may only include posts of the advertise- ment as sources of comments. However, policymakers may want to access a more extensive debate to understand how indi- viduals respond to interventions and policies. In this case, a mix of posts produced by the organi- zation and those from the general media may be used to source a balanced and diverse commentary. Fundamentally, consistent with sampling in qualitative research, the sources used need to be purposefully selected (Saldaila, 2021) to provide insight. Step 2: Once the comments are collected, each comment needs to be manually reviewed to determine its suitability prima facie. This stage determines the obvious "fit" of the comment for the research. This is achieved through a two-stage process. Stage 1: Provisional coding techniques (Creswell & Poth, 2016; Saldaa, 2021) can be used to create pre-determined inclusion or exclusion criteria before reviewing data. These criteria are best created using a team approach where all members are aligned on the type of comments that should be included versus excluded (Creswell & Poth, 2016). Such criteria can include the theme of the comment-for example, if we are looking at attitudes to pride parades, we would not include comments related to sports events. It may also include the characteristics of the postfor instance, comments that only tag other people without any reference to the post's topic may be cleaned out to reduce the level or dross in the analysis process. Stage 2: Once data have been initially screened, there may likely be comments that do not directly meet the inclusion or exclusion criteria but still prima facie appear irrelevant. A team coding approach is recommended to negotiate the relevance of these comments to the scope of the research (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). Through this process, the inclusion or exclusion criteria established may be nuanced to consider the reviewed comments (Creswell & Poth, 2016). An inter-coder approach, where reliability is ascertained by having multiple researchers code the data, may be used for projects with a high volume of such data and a limited tumaround time (Saldaa, 2021). However, the limitations of an inter-coder approach need to be considered in that it could result in the application of subjective reasoning as opposed to developing an objective criteria based on negotiation with a panel of researchers. Step 3: After the data have been manually cleansed, bot-detection programs like Botometer can then be used to scan remaining commenters or comments to identify those that appear relevant but are fabricated by bots. Botometer works by using a machine-learning algorithm to calculate a score where low scores indicate likely human accounts and high scores indicate likely bot accounts. To calculate the score, Botometer compares an account to tens of thou- sands of labeled examples (Botometer, 2021). These data are distributed to the Botometer artificial program interface, which mines more than a 1,000 structures to characterize the account's profile, friends, social network structure, temporal activity patterns, comment lan- guage, and sentiment (Botometer, 2021). Finally, the features are used by various machine learning models to compute the bot score (Botometer, 2021). Applying this process will help identify a subset of comments and user profiles that need to be removed to ensure clean data. Step 4. Due to the increased sophistication of bots and the emergence of machine learning in this space, bot, spam, and "sock-puppet" detection software may not fully identify all bot-gen- erated commentary. A team coding approach may be used to review the remaining comments manually if time and budgets permit. Key criteria for manual bot detection are provided in Table 1. These guidelines were developed initially by Ferrara et al. (2016, p. 96) and have been modi- fied herein to suit a marketing and social research setting. Through a team coding process, multiple researchers would review and classify each comment based on their assessment of the comment against the criteria provided. Once this classification is completed the group would reconvene to review and negotiate consensus. This would ensure greater accuracy of detection. If a project is large scale, the research team has an additional option. Wang et al. (2012) pro- poses crowdsourcing as an efficient means of cleaning data. Such a team coding approach can be applied using online platforms where participants review comments and classify them based Table I. Bot-detection categorization framework. Class Description Network Network features capture the various and multiple social media platforms the profile posting the comment appears on to examine the types of comments posted by the profile. This includes identifying duplicate accounts on the platform or across platforms and if the account follows a suspicious mix of sources or those previously identified as Suspicious by other organization. Users This includes profile features such as how long the profile has been active, ambiguous profile names, and photographs, the use of divisive words, and/or lots of numbers in the user profile or handle. User features may also be considered based on their meta-data, such as their geographic location. Friends Friends' features include descriptive statistics related to an account's social contacts, such as the number of followers or friends, the specific distribution or number of followers, and types of followers. For example, if we have a comment originating from an account that only has two followers, and the profile has only ever made one comment, we need to be suspicious. Also, if the followers are just random people, who also have no followers, this would be considered suspect. Timing This includes considerations of the number of posts a day, rapid changes in topic, a high number of retweets. Timing or temporal features can indicate the average time between two consecutive posts. If this time is below the human threshold, we need to consider it as a bot produced comment. Content Content features are based on linguistic cues in the posts. For example, tweeting in multiple languages, posting inflammatory content, awkward turns of phrase, hashtag spamming, signs of automation Sentiment Sentiment features represent the affect or emotions communicated in the post for example, the use of highly emotive language to push often polarizing views or a pre-determined set of criteria. The lead researcher would then need to review comments where a discrepancy is noted to make the final call (Saldaia, 2021). Case study application Three brief case studies are presented to demonstrate the cleaning process and illustrate the distortion caused if bots are not cleansed. Table 2 compares and summarizes the cases based on the process earlier. These case studies are based on the authors' research and were selected to provide contrasting examples that demonstrate the varying influence of bots, spam, and sock-puppets. We have focused on social and government case studies to demonstrate how bots, if left unchecked, could result in policies that do not capture the sentiment of the general population Case study 1: Wagga Wagga Mardi Gras, a pride parade set in a town of 67,000 people in regional New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The community event's online communication is regionally focused, small in size, using only limited channels consisting mainly of Facebook and Twitter. Case study 2: Climate and energy policy debate in Australia. Due to its divisive nature, this topic received a high level of engagement by both far-left and far-right advocacy groups. The topic has become politicized due to Australia's high level of coal exports and a lack of perceived climate action by successive governments, Case 3: Shark nets Case 2: Energy and climate policy 7.564 10,233 3,796 remaining 2,690 remaining Table 2. Case study comparative data Steps in filtering Case 1: Wagga Wax Mardi Guas Step 1. No of comments 524 initially collected Step 2. Filtered irrelevant 250 remaining comments based on topic or coding Step 3. Comments remaining 250 remaining after bot filtering using Botometer Step 4. Manual review for 250 remaining SPAM or sock-puppets Main theme or topic propagated by bots 2,956 852 remaining 2,704 remaining 781 remaining Australia is a minor emitter of carbon Economy is more important than nature Blame India and China Human have rights over sharks Think of the children's safety Linking sharks and terrorism "Sharks are a species of peace" (n=11) "A human life is worth more than a sharks life (n=28) Examples of discarded bot comments No examples noted "Australia produces less than 1% of global emissions" (35) "Why focus on Australia? Get china and India to do more" (n=33) Case study 3: Shark nets are a controversial topic in many countries. In NSW, Australia, shark nets have been a debated topic since a string of fatal shark attacks in 2015. Multiple advocacy groups and far-right media groups have engaged in the mitigation debate. Discussion and implications As illustrated in the three cases above, social media data need to be cleaned before being used as part of research. We argue this cleaning must happen manually to exclude comments that prima facie do not fit the objective or purpose of the research, and then by using bot-detection software to identify fabricated comments that otherwise may be hard to identify. Although representing the political point of view of an individual or group, the comments made by bots could skew the data to represent views not popularly held. For instance, blaming India and China while arguing eco- nomic gains are more important than nature in Case 2, and fear-mongering by explaining that sharks could hurt children in the context of Case 3. However, the infiltration by bots may differ based on the context as shown by Case I, which is a small community event, compared to Cases 2 and 3, which relate to national policies. A core component of social listening theory is the authenticity of voice and the notion that listen- ing itself is a "profound democratic act" (Macnamara, 2016, p. 30). However, Macnamara warns that although many scholars across disciplines related to communication are celebratory in their discussions on social media and Web 2.0, no guarantee exists that these technological innovations will ensure people are heard or listened to by those informing or influencing decision-making. Bots Table 3. Positive and negative implication for practice. Positive More accurate insights into attitudes, preferences, and reasoning Increased reliability of recommendations. Protects the reputation of the researcher and the credibility of the research process. Appropriate allocation of resources improved. Negative Time-consuming, especially with more extensive datasets. Costly Requires advanced skills, particularly linguistics and computational represent a challenge to the core democratie nature of social listening. The conceptual model out- lined in the article contributes to and strengthens social listening theory by ensuring that its demo- cratic nature and power are preserved in favor of those who should ultimately benefitthat is, the citizens. The positive and negative implications for practice are summarized in Table 3. In sum, social bots present a real risk for marketers and policymakers in understanding attitudes and preferences. Bot data must be removed from datasets to ensure that recommendations devel- oped are truly representative of the target market and do not leave the research open to criticism. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. International Journal of Market Research Research Note Lots of bots or maybe nots: A process for detecting bots in social media research International journal of Market Research 2021, Vol. 625) 552-559 The Author(s) 2021 Article reuse guidelines gepub.com/journals permissions DOE 10.1177/14707853211027486 journals.sagepub.com/home/mre SSAGE Michael Mehmet University of Wollongong. Australia Kane Callaghan and Clifford Lewis Charles Sturt University, Australia Abstract The use of bot messaging that being artificially created messages, has increased since 2010. While not all bots are bad, many have been used to share extreme and divisive views on a range of topics, from policy discussion to brand electronic word of mouth. The issue with bot messaging and its prevalence is that it can affect researchers' understanding of a topic. For example, if 25% of a dataset is fabricated decision-making may result in a loss of profit or poor policy formation. To counteract the use of bots, this research note offers a framework to alleviate the potentially destructive nature of bot data and ensure the cleaning of data is thorough and beneficial to decision-making based on social media commentary. The framework is a four-step process, which includes thematic, automated, and characteristic identification stages. We provide three case studies to demonstrate the approach and conclude by providing key practical implications. Keywords bots, cleaning, filtering, sentiment, social media Introduction Social media data have become an alluring source of insight into the mindsets of the general popu- lation by providing a relatively cheap, quick, and easy-to-access source of data (Graham et al., 2020). These benefits align with shrinking corporate and academic budgets and time pressures to turnaround projects, particularly exacerbated by COVID-19. However, this perceived panacea comes with risks (Kozinets, 2019), which, if not addressed appropriately, can contaminate results and findings (Saldaia, 2021) making it almost impossible to provide accurate, evidence-based conclusions and recommendations. This research note will provide a framework to assist in over- coming a key issue, that being bot messaging contaminating social media data. Netnography guru Kozinets (2019) strongly advocates filtering as a vital step in ensuring the authenticity and usability of online sourced community and consumer data. Such filtering may happen at two levels-first at a thematic level, to exclude comments that do not fit the research- er's criteria, and second, to exclude those that prima facie appear authentic but may be fabricated. Recent studies (Crabb et al., 2015; Freelon et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2020) have highlighted the concern of highly organized online activists who can influence and contaminate data with the use of bots (automated content creation tools), spam (mass communication messaging), and "sock- puppets" (a fake account designed to distort and manipulate public opinion). Despite acknowl- edging the challenges in using social media data, few studies have explored this process and how it may be applied effectively in practice (Graham et al., 2020). This article, therefore, provides a structured approach that industry and academic researchers can apply when using social media data. Social media research typically involves analyzing comments made in response to posts that discuss a relevant topic or present an idea of interest to the researcher (Liu, 2010). The data col- lected can provide insight into consumers' responses to various topics, from brands to government policy (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). For brands, it can provide rapid insights on new marketing programs, helping the brand assess and correct campaigns efficiently (Snchez-Nuez et al., 2020). Similarly, governments may use social media commentary to understand their constituents' needs and their response to new policies (Hubert et al., 2020). By understanding these responses, policy- makers can gain clear insights into peoples' attitudes and preferences (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019), enabling govemments to amend policies or implement additional communication campaigns or interventions to enhance compliance. In the context of social marketing, Hubert et al. (2020) explain that social listening is an essential component to designing interventions that have a social impact. Dobson (2014) similarly argues that centralizing "listening at or near the heart of the demo- cratic process leads us in the direction of dialogie democracy" (p. 6). Consistent in Mehmet and Simmons (2019) and Dobson (2014) is the need for policymakers to engage and seek feedback from those affected by the policies developed. Such feedback helps ensure policies align with the nuances of those being affected by them-thus, helping to ensure greater compliance and better implementation outcomes (French & Gordon, 2019). Social media can play a role in assisting to expedite the feedback process. To use social media data effectively, it is essential to address data appropriateness (Kozinets, 2019). A problem, however, lies in assessing data that looks like a natural response but is fabricated by software robots (bots), which are algorithms designed to engage in human-like conversations (Bollen et al., 2011; Ferrara et al., 2016). Bots have been skewing social media discussions for nearly a decade (Wiesenberg & Tench, 2020). These bots have fake names, biographies, and pho- tographs, and newer bots have even evolved to have personalitiesmaking it difficult to distin- guish the language they use from other authentic posts. Bots can skew social discourse by suggesting, reinforcing, and conflating views that the major- ity may not hold-and, in doing so, silence opposing debates by making them appear as a minority (Ferrara, 2020; Graham et al., 2020). This "filter bubble" effect (Pariser, 2011) creates a curated content echo chamber of public opinion (Bozdag & van den Hoven, 2015). For marketers or poli- cymakers attempting to influence brand or policy, bots can infiltrate discourse (Schneier, 2020), spread misinformation, and skew the insights developed (Daniel et al., 2019; Reuter & Lee, 2019). To illustrate their significance, reports indicate bots published nearly one-fifth of all tweets about the 2016 US presidential election, and according to one estimate, about one-third of all tweets about that year's Brexit vote (Ferrara, 2020). This highlights the need to screen posts when using them as part of the research process to ensure credibility (Ferrara, 2020; Ferrara et al., 2016) and validity (Reuter & Lee, 2019). We acknowledge that not all bots are bad or designed to be nefarious, and some may be created by authorized accounts like government agencies to inform the population (Allem et al., 2017; Ledford, 2020). However, this article focuses on bots that pose as average consumers with the intent of misleading or skewing commentary on social media. We put forward an approach that may be used to enhance the quality of social media research by implementing a data cleaning and bot-detection process. Importantly, this study focuses on the process of cleansing, rather than advo- cating for particular bot-detection programs or services, of which there are many in the market- place. The reason for this is twofold, first, the literature extensively examines the effectiveness of bot-detection software, and second, despite acknowledging the effectiveness of such software, lit- tle has been written on incorporating bot detection into current research processes and designs (see Cai et al., 2017, Hui et al., 2019; Kudugunta & Ferrara, 2018; Yang et al., 2020). This article pre- sents a process that can be followed, and then illustrates the process with brief case studies designed to highlight the implications in practice. Data cleaning and bot-detection approach Social listening procedures typically follow a set of steps associated with traditional research meth- ods, which include establishing aims, defining scope, collecting data, filtering and cleaning the data, coding and analysis, and reporting (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). There are two potential approaches when incorporating bot-detection stages in the cleaning processes. The first approach includes using an automated bot-detection tool, which filters potential bot data before the researcher sees the raw data (Hui et al., 2019). A manual process in then used to filter data based on relevance to the research aims and inclusion or exclusion protocols (Saldaila, 2021). The advantage of this approach is speed; however, one major downfall is not being exposed to bot-created content, which has been shown to affect online sentiment and opinion (Graham et al., 2020). Hence, we propose an alternative approach wherein bot detection is applied after an initial review of the raw data. The advantage of this approach is that it allows the researcher to identify bot-created comments and interpret them in context. Furthermore, it assists in understanding how the bot-created comments have potentially affected or biased other participants' views of the world, the type of commentary they share, and the topic of discussion more broadly. This approach is now discussed considering the stages of data collection and filtering when using social media as a source of data. Step 1. Software like Facepage or exporteomments provides a platform where researchers can export comments relating to specific social media postsfor instance, a news article that discusses a policy or an advertisement or information post. Typically, these platforms allow the researcher to export comments in comma-separated values (CSV) format. Kozinets (2019) cautions that researchers must immerse themselves in the research area to ensure a higher likelihood of quality data. This immersion includes identifying posts that can be used as sources for comments. In some instances, these sources could be very narrow-for example, if a marketer was trying to establish how consumers respond to a specific advertisement, they may only include posts of the advertise- ment as sources of comments. However, policymakers may want to access a more extensive debate to understand how indi- viduals respond to interventions and policies. In this case, a mix of posts produced by the organi- zation and those from the general media may be used to source a balanced and diverse commentary. Fundamentally, consistent with sampling in qualitative research, the sources used need to be purposefully selected (Saldaila, 2021) to provide insight. Step 2: Once the comments are collected, each comment needs to be manually reviewed to determine its suitability prima facie. This stage determines the obvious "fit" of the comment for the research. This is achieved through a two-stage process. Stage 1: Provisional coding techniques (Creswell & Poth, 2016; Saldaa, 2021) can be used to create pre-determined inclusion or exclusion criteria before reviewing data. These criteria are best created using a team approach where all members are aligned on the type of comments that should be included versus excluded (Creswell & Poth, 2016). Such criteria can include the theme of the comment-for example, if we are looking at attitudes to pride parades, we would not include comments related to sports events. It may also include the characteristics of the postfor instance, comments that only tag other people without any reference to the post's topic may be cleaned out to reduce the level or dross in the analysis process. Stage 2: Once data have been initially screened, there may likely be comments that do not directly meet the inclusion or exclusion criteria but still prima facie appear irrelevant. A team coding approach is recommended to negotiate the relevance of these comments to the scope of the research (Mehmet & Simmons, 2019). Through this process, the inclusion or exclusion criteria established may be nuanced to consider the reviewed comments (Creswell & Poth, 2016). An inter-coder approach, where reliability is ascertained by having multiple researchers code the data, may be used for projects with a high volume of such data and a limited tumaround time (Saldaa, 2021). However, the limitations of an inter-coder approach need to be considered in that it could result in the application of subjective reasoning as opposed to developing an objective criteria based on negotiation with a panel of researchers. Step 3: After the data have been manually cleansed, bot-detection programs like Botometer can then be used to scan remaining commenters or comments to identify those that appear relevant but are fabricated by bots. Botometer works by using a machine-learning algorithm to calculate a score where low scores indicate likely human accounts and high scores indicate likely bot accounts. To calculate the score, Botometer compares an account to tens of thou- sands of labeled examples (Botometer, 2021). These data are distributed to the Botometer artificial program interface, which mines more than a 1,000 structures to characterize the account's profile, friends, social network structure, temporal activity patterns, comment lan- guage, and sentiment (Botometer, 2021). Finally, the features are used by various machine learning models to compute the bot score (Botometer, 2021). Applying this process will help identify a subset of comments and user profiles that need to be removed to ensure clean data. Step 4. Due to the increased sophistication of bots and the emergence of machine learning in this space, bot, spam, and "sock-puppet" detection software may not fully identify all bot-gen- erated commentary. A team coding approach may be used to review the remaining comments manually if time and budgets permit. Key criteria for manual bot detection are provided in Table 1. These guidelines were developed initially by Ferrara et al. (2016, p. 96) and have been modi- fied herein to suit a marketing and social research setting. Through a team coding process, multiple researchers would review and classify each comment based on their assessment of the comment against the criteria provided. Once this classification is completed the group would reconvene to review and negotiate consensus. This would ensure greater accuracy of detection. If a project is large scale, the research team has an additional option. Wang et al. (2012) pro- poses crowdsourcing as an efficient means of cleaning data. Such a team coding approach can be applied using online platforms where participants review comments and classify them based Table I. Bot-detection categorization framework. Class Description Network Network features capture the various and multiple social media platforms the profile posting the comment appears on to examine the types of comments posted by the profile. This includes identifying duplicate accounts on the platform or across platforms and if the account follows a suspicious mix of sources or those previously identified as Suspicious by other organization. Users This includes profile features such as how long the profile has been active, ambiguous profile names, and photographs, the use of divisive words, and/or lots of numbers in the user profile or handle. User features may also be considered based on their meta-data, such as their geographic location. Friends Friends' features include descriptive statistics related to an account's social contacts, such as the number of followers or friends, the specific distribution or number of followers, and types of followers. For example, if we have a comment originating from an account that only has two followers, and the profile has only ever made one comment, we need to be suspicious. Also, if the followers are just random people, who also have no followers, this would be considered suspect. Timing This includes considerations of the number of posts a day, rapid changes in topic, a high number of retweets. Timing or temporal features can indicate the average time between two consecutive posts. If this time is below the human threshold, we need to consider it as a bot produced comment. Content Content features are based on linguistic cues in the posts. For example, tweeting in multiple languages, posting inflammatory content, awkward turns of phrase, hashtag spamming, signs of automation Sentiment Sentiment features represent the affect or emotions communicated in the post for example, the use of highly emotive language to push often polarizing views or a pre-determined set of criteria. The lead researcher would then need to review comments where a discrepancy is noted to make the final call (Saldaia, 2021). Case study application Three brief case studies are presented to demonstrate the cleaning process and illustrate the distortion caused if bots are not cleansed. Table 2 compares and summarizes the cases based on the process earlier. These case studies are based on the authors' research and were selected to provide contrasting examples that demonstrate the varying influence of bots, spam, and sock-puppets. We have focused on social and government case studies to demonstrate how bots, if left unchecked, could result in policies that do not capture the sentiment of the general population Case study 1: Wagga Wagga Mardi Gras, a pride parade set in a town of 67,000 people in regional New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The community event's online communication is regionally focused, small in size, using only limited channels consisting mainly of Facebook and Twitter. Case study 2: Climate and energy policy debate in Australia. Due to its divisive nature, this topic received a high level of engagement by both far-left and far-right advocacy groups. The topic has become politicized due to Australia's high level of coal exports and a lack of perceived climate action by successive governments, Case 3: Shark nets Case 2: Energy and climate policy 7.564 10,233 3,796 remaining 2,690 remaining Table 2. Case study comparative data Steps in filtering Case 1: Wagga Wax Mardi Guas Step 1. No of comments 524 initially collected Step 2. Filtered irrelevant 250 remaining comments based on topic or coding Step 3. Comments remaining 250 remaining after bot filtering using Botometer Step 4. Manual review for 250 remaining SPAM or sock-puppets Main theme or topic propagated by bots 2,956 852 remaining 2,704 remaining 781 remaining Australia is a minor emitter of carbon Economy is more important than nature Blame India and China Human have rights over sharks Think of the children's safety Linking sharks and terrorism "Sharks are a species of peace" (n=11) "A human life is worth more than a sharks life (n=28) Examples of discarded bot comments No examples noted "Australia produces less than 1% of global emissions" (35) "Why focus on Australia? Get china and India to do more" (n=33) Case study 3: Shark nets are a controversial topic in many countries. In NSW, Australia, shark nets have been a debated topic since a string of fatal shark attacks in 2015. Multiple advocacy groups and far-right media groups have engaged in the mitigation debate. Discussion and implications As illustrated in the three cases above, social media data need to be cleaned before being used as part of research. We argue this cleaning must happen manually to exclude comments that prima facie do not fit the objective or purpose of the research, and then by using bot-detection software to identify fabricated comments that otherwise may be hard to identify. Although representing the political point of view of an individual or group, the comments made by bots could skew the data to represent views not popularly held. For instance, blaming India and China while arguing eco- nomic gains are more important than nature in Case 2, and fear-mongering by explaining that sharks could hurt children in the context of Case 3. However, the infiltration by bots may differ based on the context as shown by Case I, which is a small community event, compared to Cases 2 and 3, which relate to national policies. A core component of social listening theory is the authenticity of voice and the notion that listen- ing itself is a "profound democratic act" (Macnamara, 2016, p. 30). However, Macnamara warns that although many scholars across disciplines related to communication are celebratory in their discussions on social media and Web 2.0, no guarantee exists that these technological innovations will ensure people are heard or listened to by those informing or influencing decision-making. Bots Table 3. Positive and negative implication for practice. Positive More accurate insights into attitudes, preferences, and reasoning Increased reliability of recommendations. Protects the reputation of the researcher and the credibility of the research process. Appropriate allocation of resources improved. Negative Time-consuming, especially with more extensive datasets. Costly Requires advanced skills, particularly linguistics and computational represent a challenge to the core democratie nature of social listening. The conceptual model out- lined in the article contributes to and strengthens social listening theory by ensuring that its demo- cratic nature and power are preserved in favor of those who should ultimately benefitthat is, the citizens. The positive and negative implications for practice are summarized in Table 3. In sum, social bots present a real risk for marketers and policymakers in understanding attitudes and preferences. Bot data must be removed from datasets to ensure that recommendations devel- oped are truly representative of the target market and do not leave the research open to criticism. Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article