Question: IDEO Case Study Assignment What are features of IDEO's Exploratory Phase? (select all that apply) Team members share different insights they have gained in downloading

IDEO Case Study Assignment

-

What are features of IDEO's "Exploratory Phase"? (select all that apply)

| | | Team members share different insights they have gained in downloading sessions |

| | | Extended interviews with potential clients |

| | | Watching users interact with a product or service in real time |

| | | Presenting potential solutions to the client |

QUESTION 2

-

What are features of the "Prototyping Phase"? (select all that apply)

| | | Creating profiles of customers and what they wanted |

| | | Quick "mock-ups" of possible solutions based on observations of customers |

| | | Conversations with client employees about how their experiences with prototypes |

| | | Prototypes could be intangible things like a new script for client interactions |

QUESTION 3

-

What comprises IDEO's "Concepting Phase: Ideation"? (select all that apply)

| | | Debate on the merits of each idea |

| | | Sharing and testing concepts with the client (e.g. Cineplanet) |

| | | A range of ideas that is very broad |

| | | Abandoning or refining ideas that were on the wrong track |

QUESTION 4

-

The following are factors contributing to IDEO's recipe for innovation: (select all that apply)

| | | Hiring people who can work independently from others |

| | | Embracing ambiguity |

| | | Teams comprised of people from multiple disciplines |

| | | Involving the client in the creative process |

QUESTION 5

-

One of Cineplanet's goals was to get people to come to the cinema for more than just the movie, popcorn, and soft drinks.

True

False

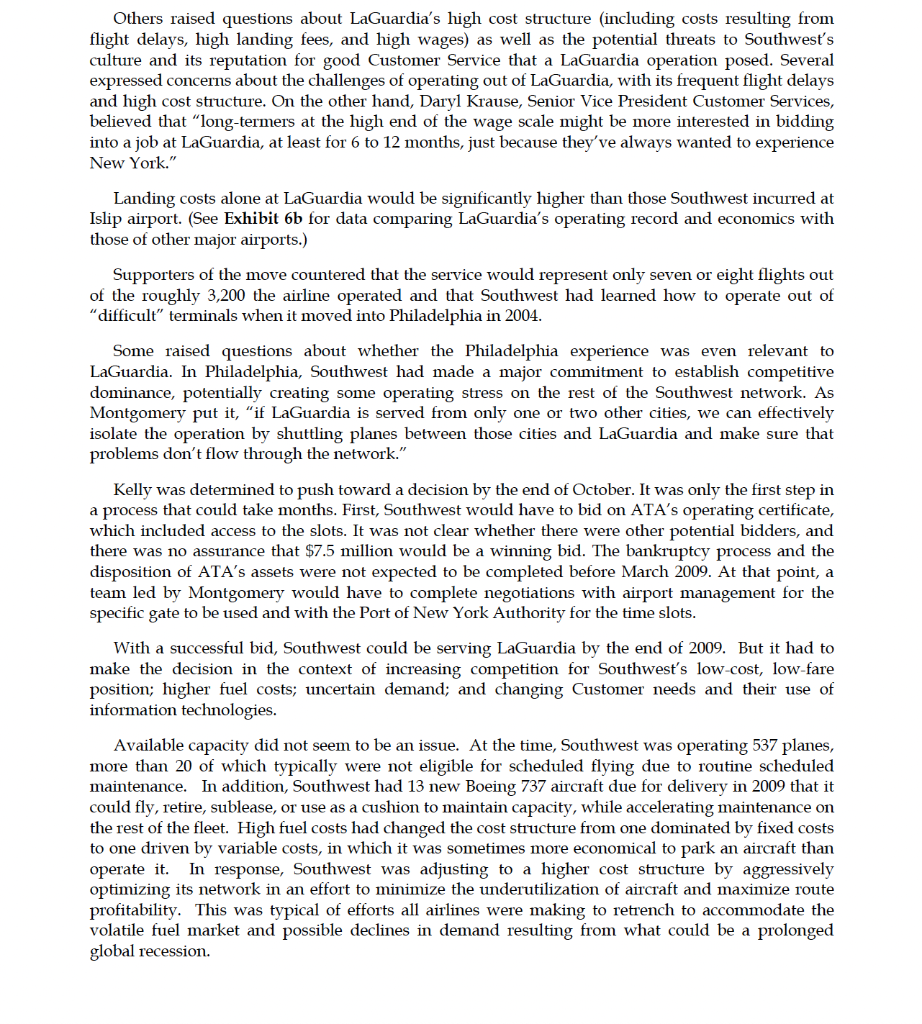

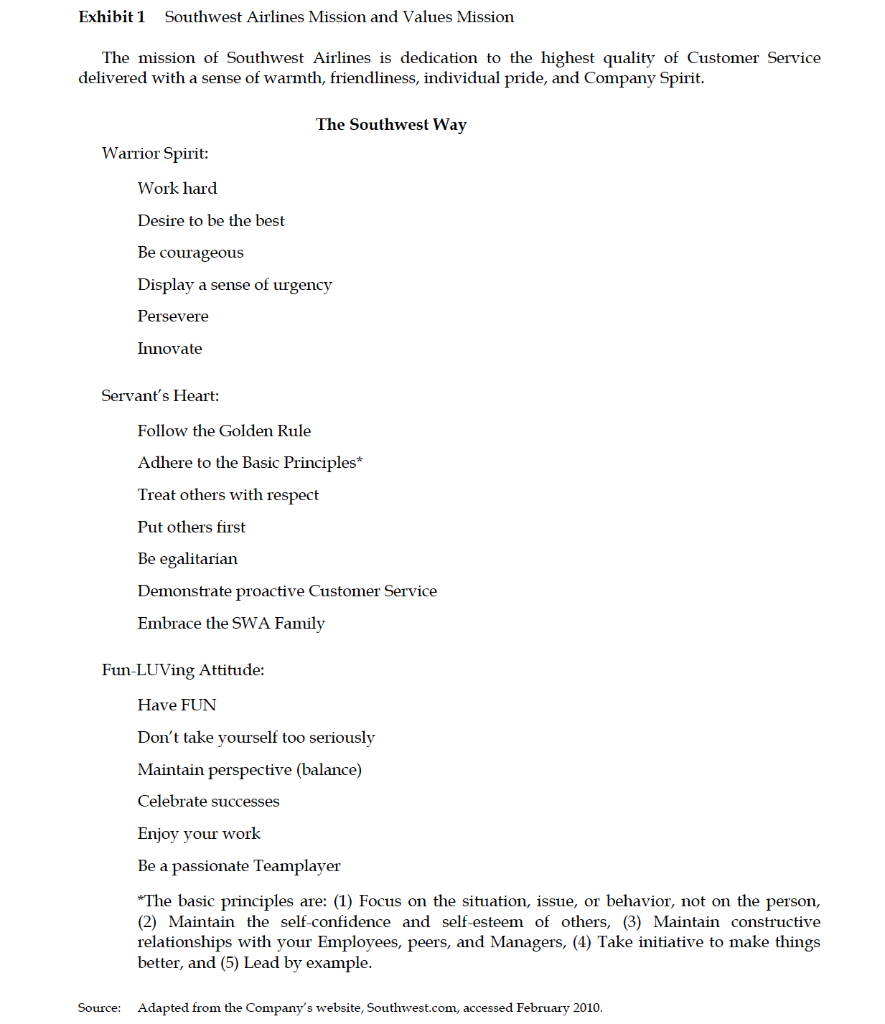

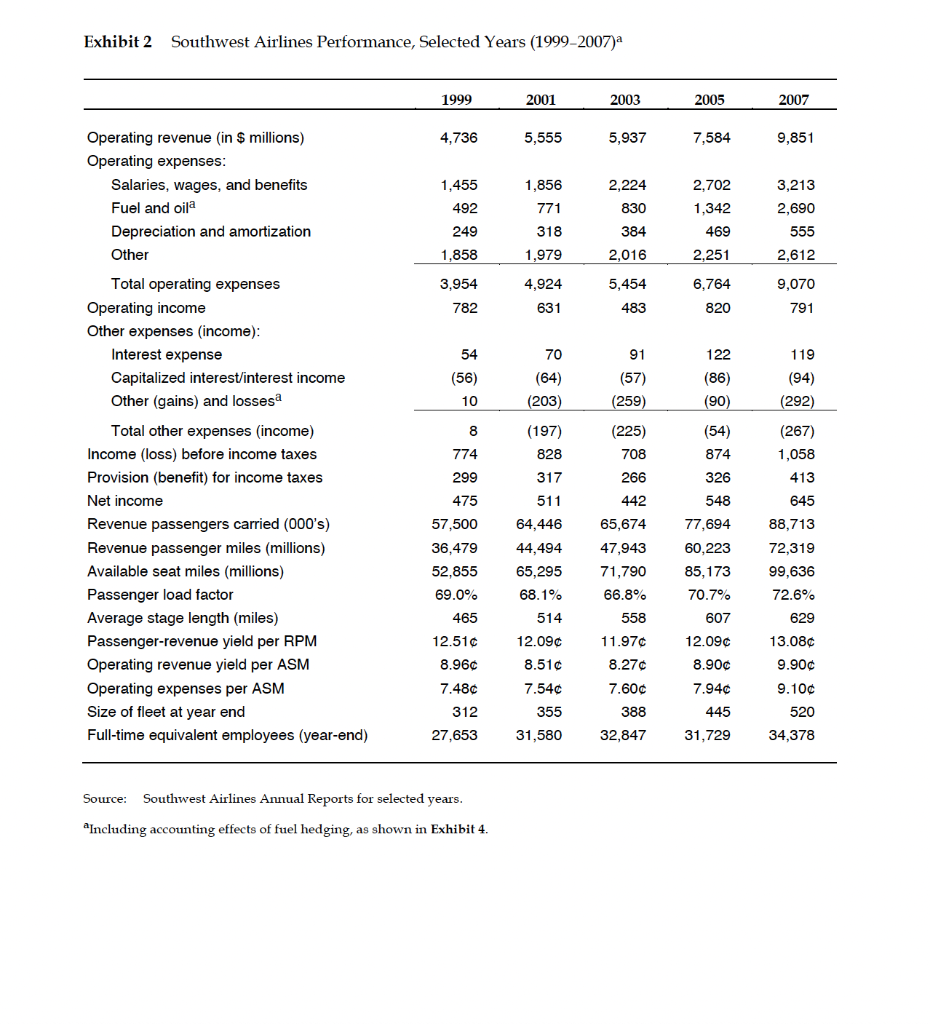

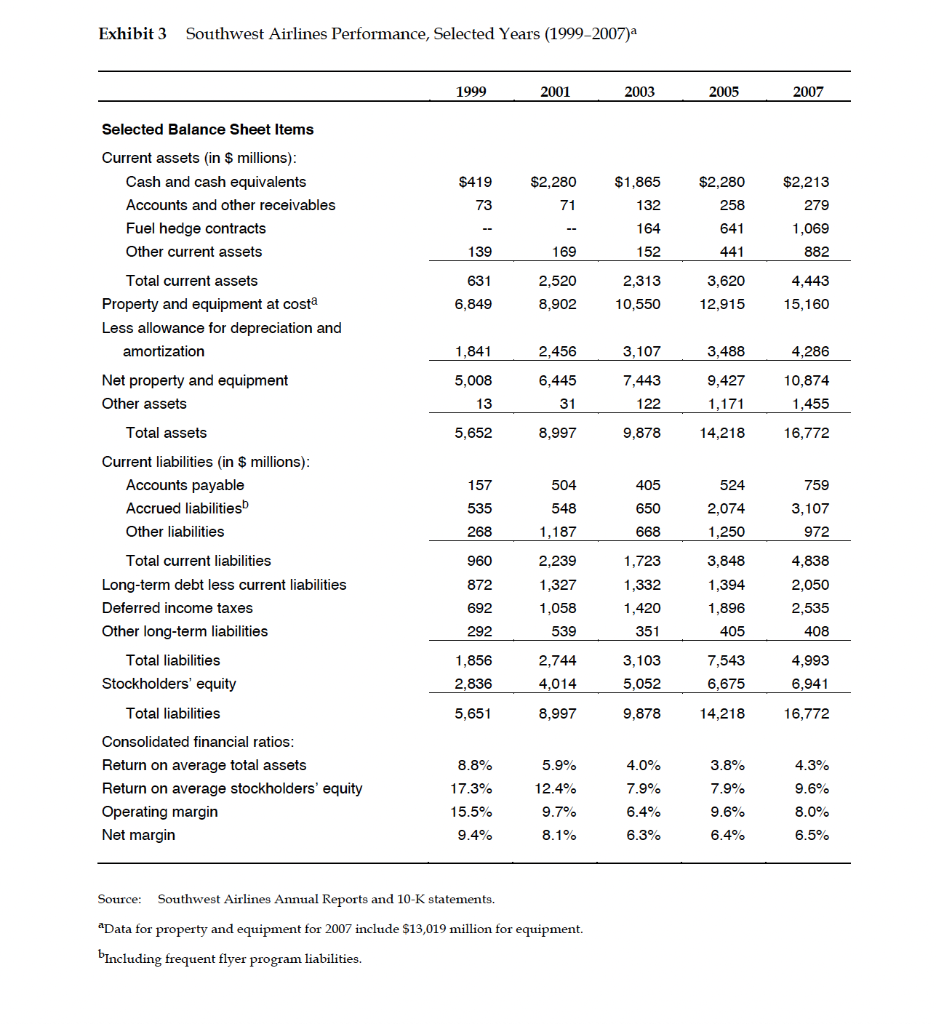

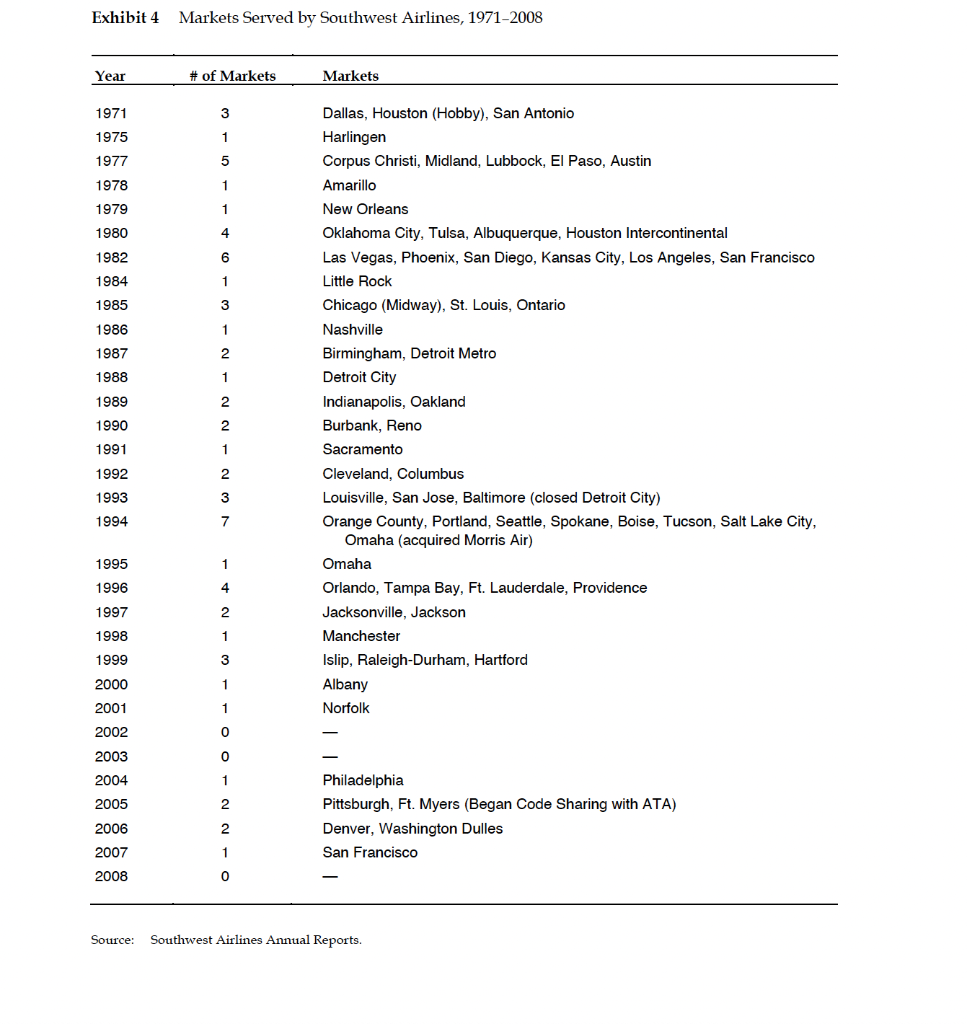

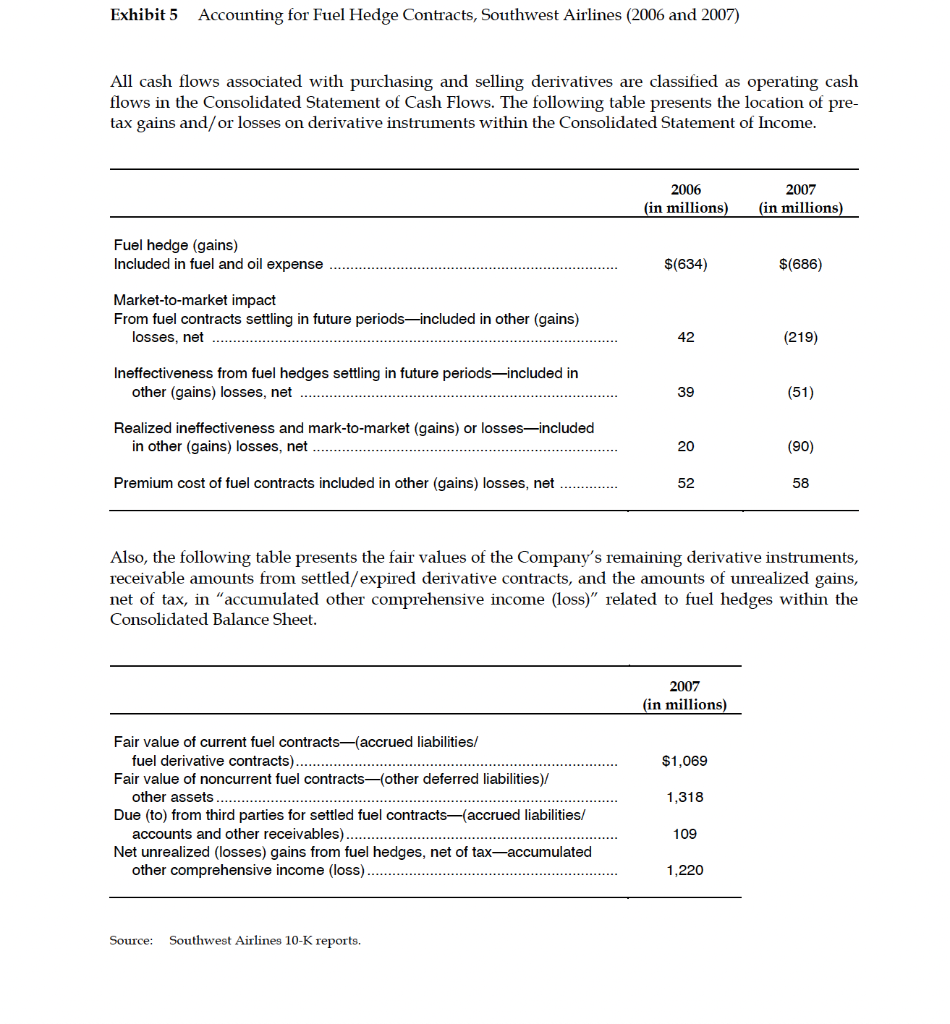

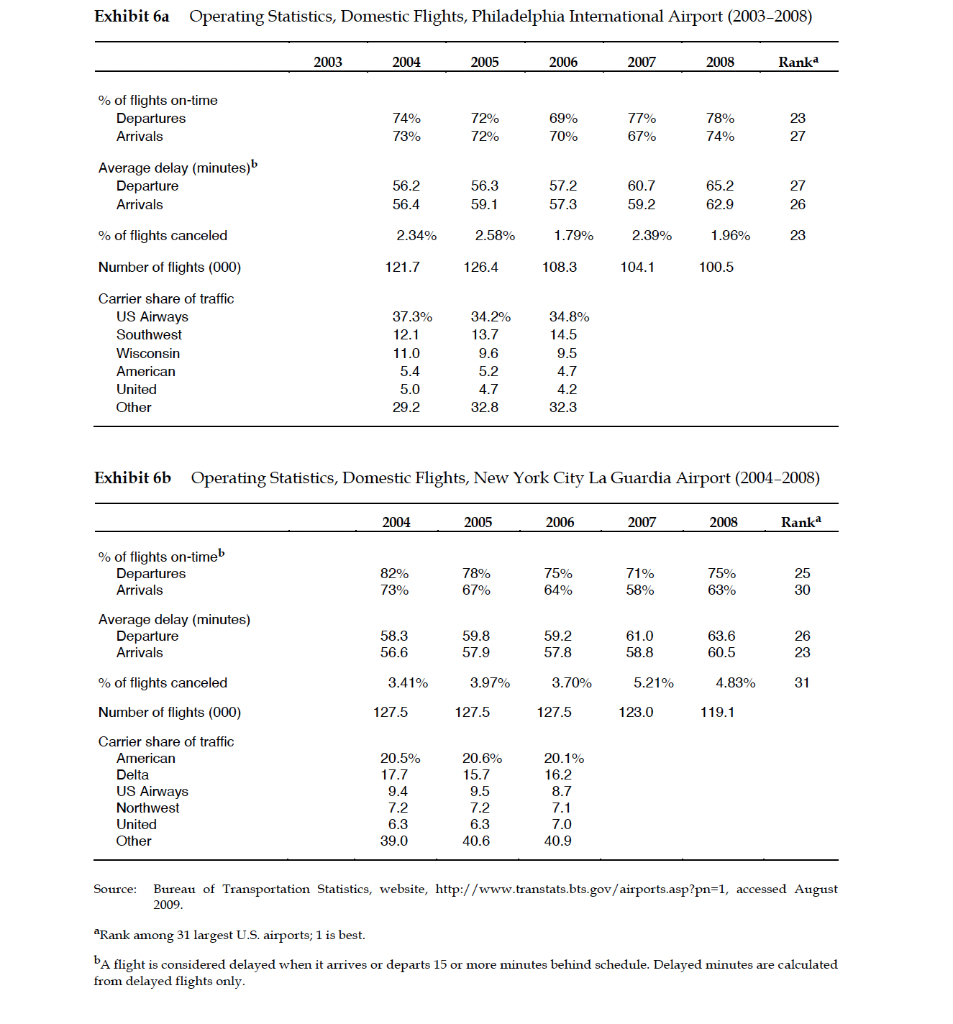

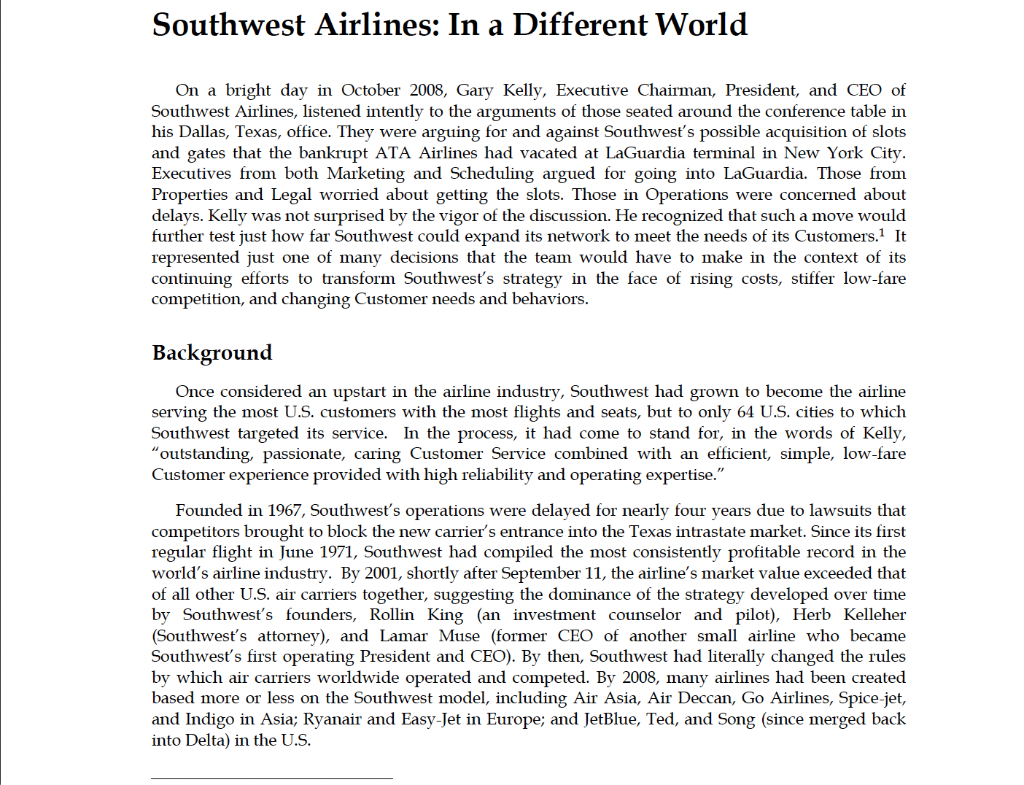

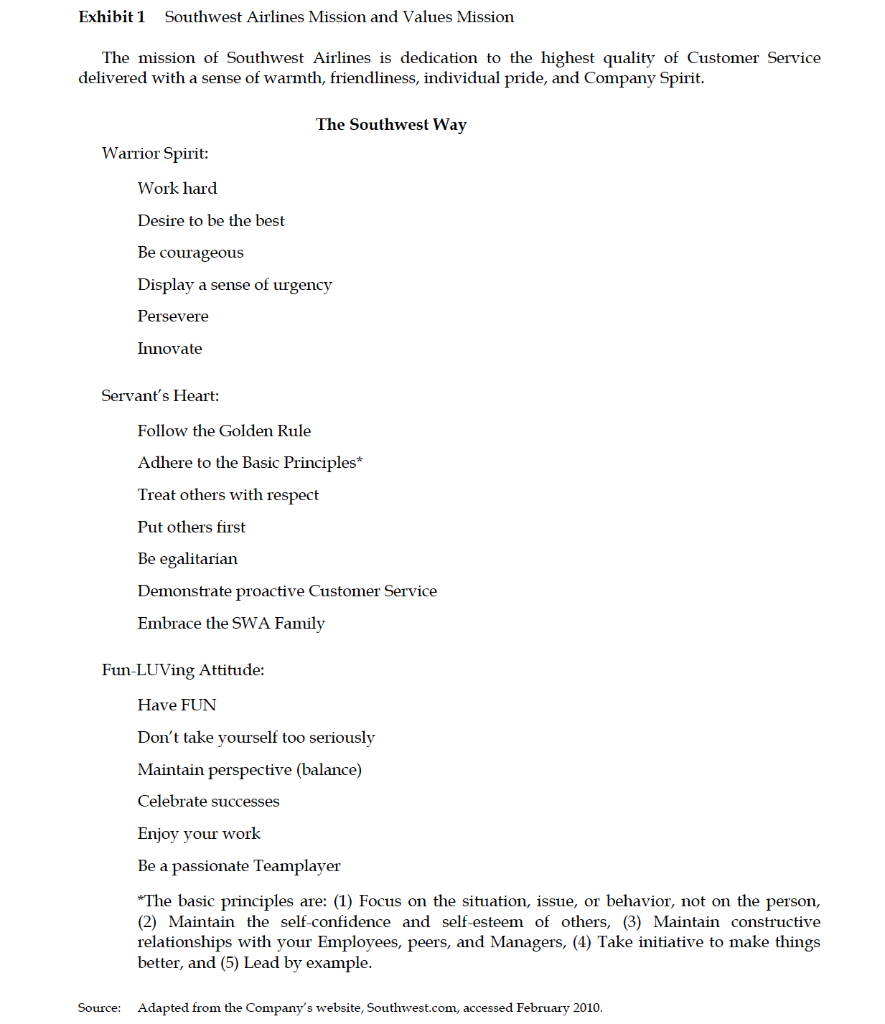

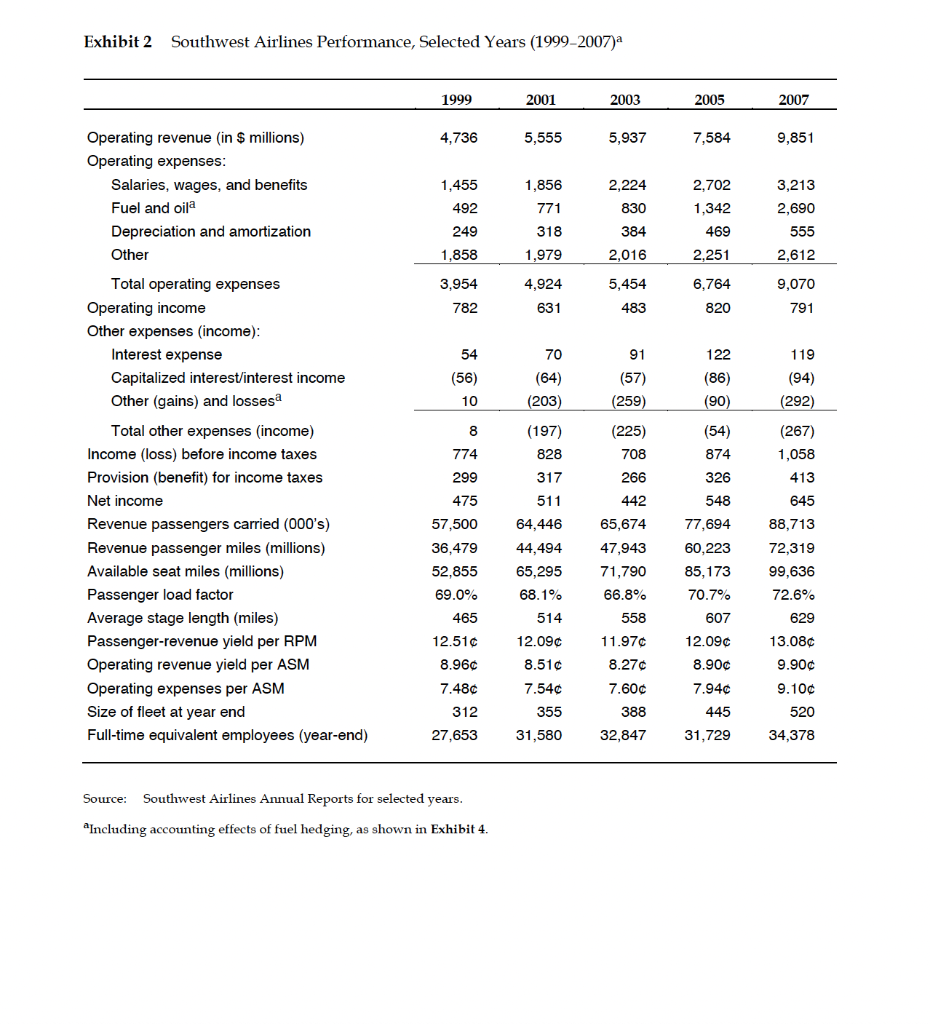

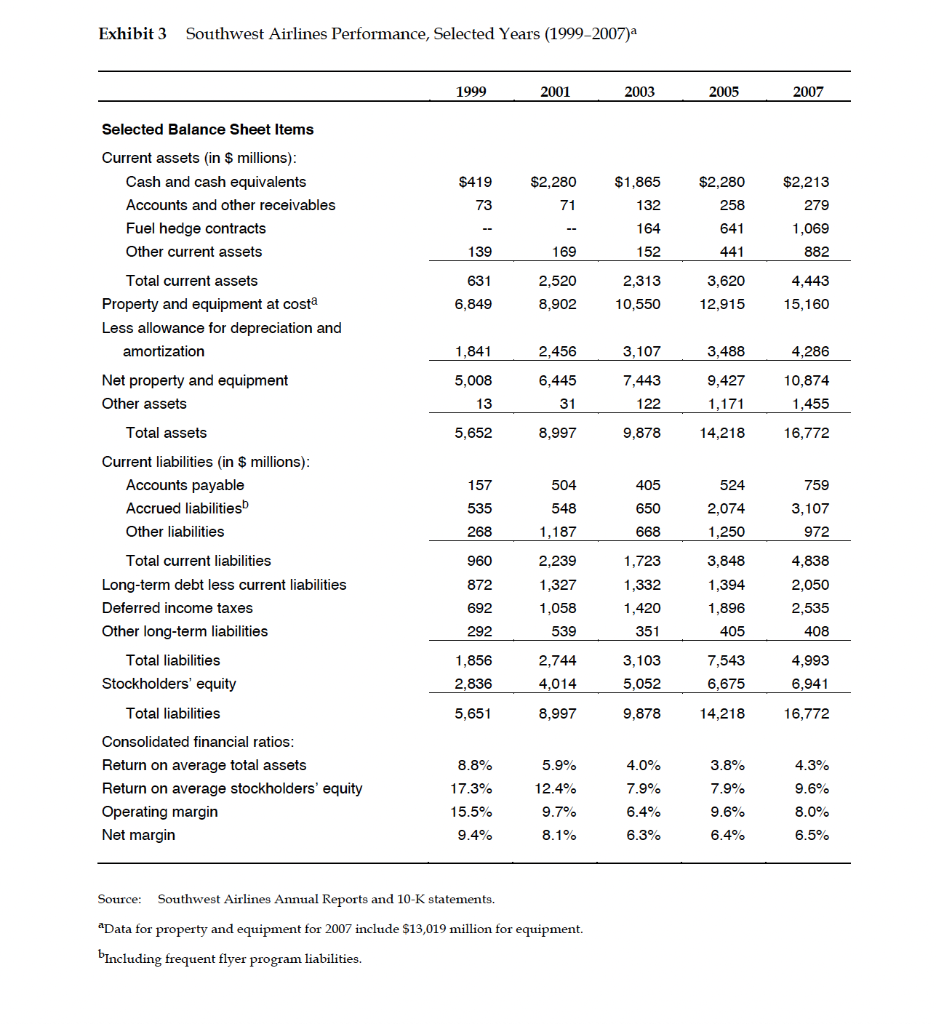

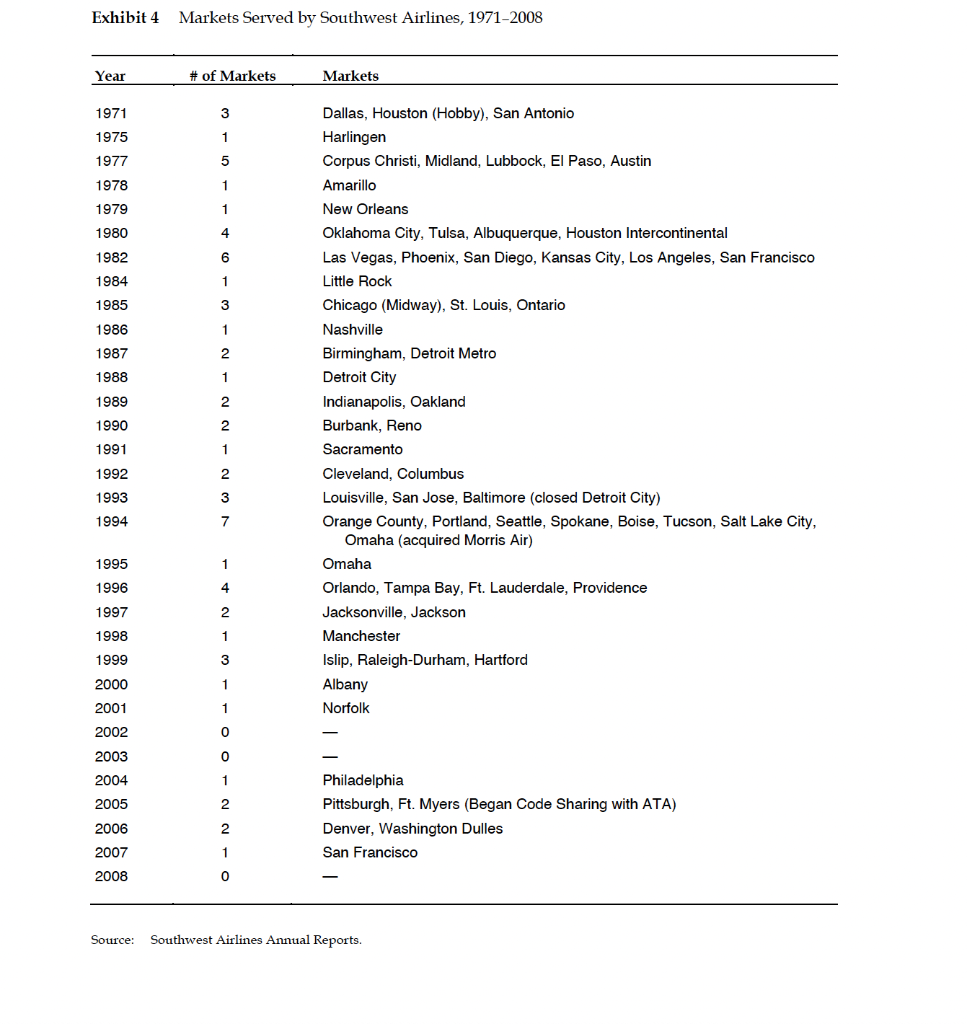

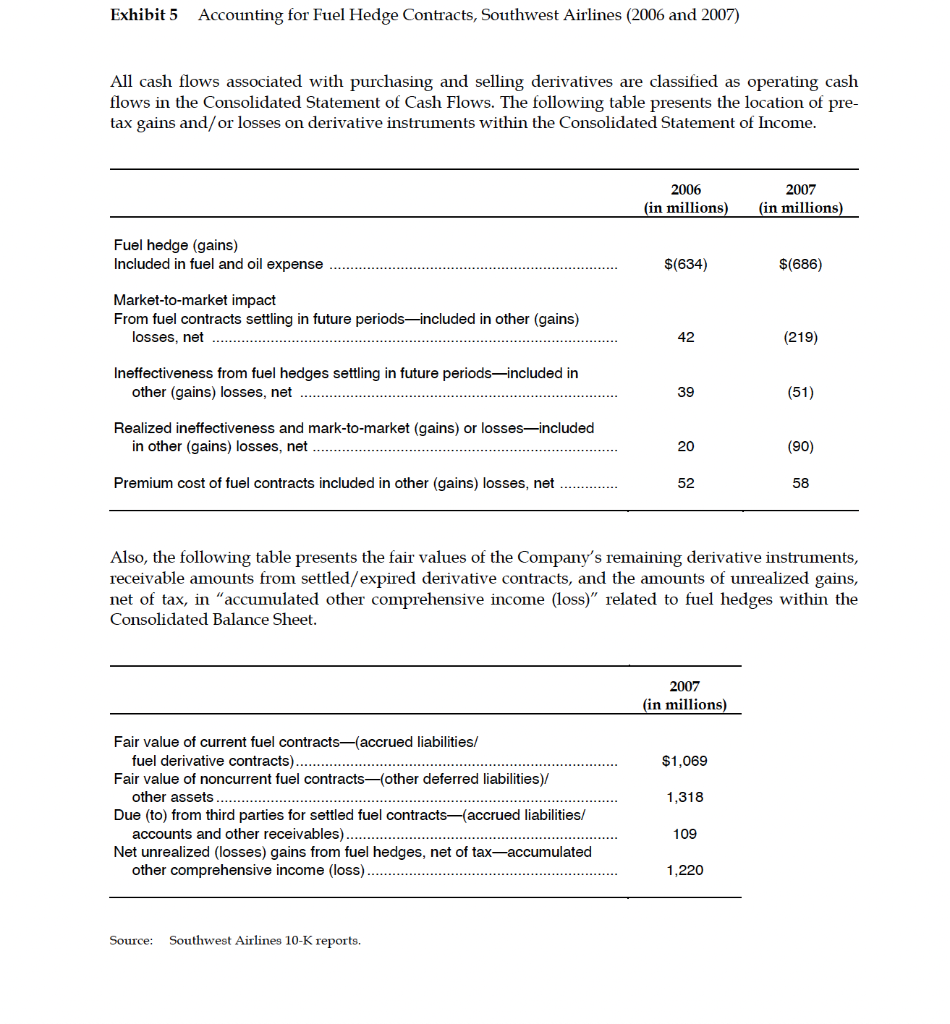

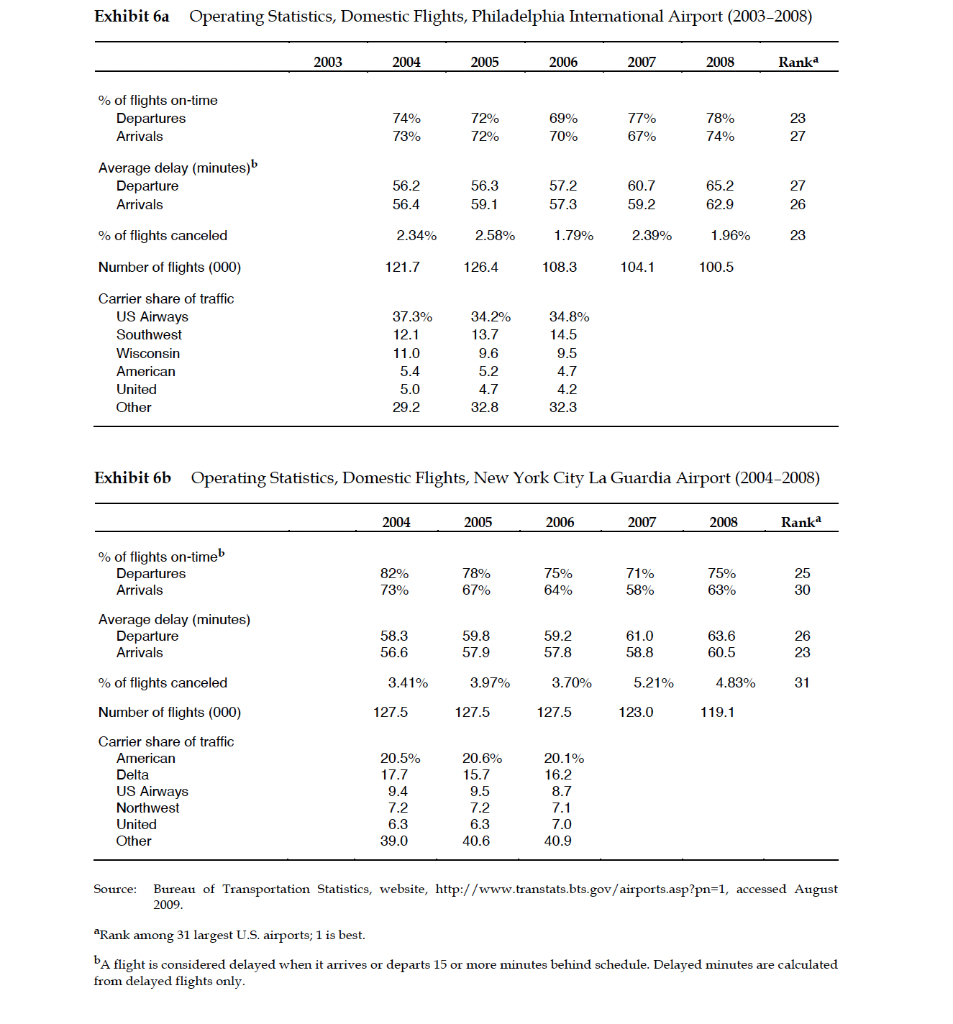

Southwest Airlines: In a Different World On a bright day in October 2008, Gary Kelly, Executive Chairman, President, and CEO of Southwest Airlines, listened intently to the arguments of those seated around the conference table in his Dallas, Texas, office. They were arguing for and against Southwest's possible acquisition of slots and gates that the bankrupt ATA Airlines had vacated at LaGuardia terminal in New York City. Executives from both Marketing and Scheduling argued for going into LaGuardia. Those from Properties and Legal worried about getting the slots. Those in Operations were concerned about delays. Kelly was not surprised by the vigor of the discussion. He recognized that such a move would further test just how far Southwest could expand its network to meet the needs of its Customers. It represented just one of many decisions that the team would have to make in the context of its continuing efforts to transform Southwest's strategy in the face of rising costs, stiffer low-fare competition, and changing Customer needs and behaviors. Background Once considered an upstart in the airline industry, Southwest had grown to become the airline serving the most U.S. customers with the most flights and seats, but to only 64 U.S. cities to which Southwest targeted its service. In the process, it had come to stand for, in the words of Kelly, outstanding, passionate, caring Customer Service combined with an efficient, simple, low-fare Customer experience provided with high reliability and operating expertise." Founded in 1967, Southwest's operations were delayed for nearly four years due to lawsuits that competitors brought to block the new carrier's entrance into the Texas intrastate market. Since its first regular flight in June 1971, Southwest had compiled the most consistently profitable record in the world's airline industry. By 2001, shortly after September 11, the airline's market value exceeded that of all other U.S. air carriers together, suggesting the dominance of the strategy developed over time by Southwest's founders, Rollin King (an investment counselor and pilot), Herb Kelleher (Southwest's attorney), and Lamar Muse (former CEO of another small airline who became Southwest's first operating President and CEO). By then, Southwest had literally changed the rules by which air carriers worldwide operated and competed. By 2008, many airlines had been created based more or less on the Southwest model, including Air Asia, Air Deccan, Go Airlines, Spice-jet, and Indigo in Asia; Ryanair and Easy-Jet in Europe; and JetBlue, Ted, and Song (since merged back into Delta) in the U.S. Southwest's beginnings were not auspicious. Because of their plan to charge fares that were at least 60% lower than the average coach fare, its founders did not want to be regulated by the Civil Aeronautics Board, which set airline routes and fares for interstate carriers. Having seen the success of intrastate carriers Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) and Air Cal, Southwest's founders mapped a triangular intrastate route connecting Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, cities located about an hour (by air) from each other, and in 1967 applied for authority from the Texas Aeronautics Commission to serve them. Two interstate competitors, Braniff and Texas International, sued to enjoin Southwest from flying, a suit that was eventually resolved in Southwest's favor by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1971. King, Muse, and Kelleher consulted with Air Cal on a number of issues, including the decision initially to purchase three aircraft. (They bought a fourth shortly thereafter.) The Boeing Company, which had overproduced its Boeing 737 twin jet (a result of an overestimation of the market), was willing to sell each plane for $4.1 million, $500,000 below the initial asking price, and provide favorable financing terms. Thus began a relationship that would create Boeing's best customer. It also launched Southwest as a carrier that utilized only Boeing 737s, 537 of them by 2008. Price competition from interstate competitors was ferocious. According to Colleen Barrett, President Emeritus, "we knew that we were going to have to have substantially lower fares on day one of our operation than were currently being charged because that was our only chance of winning a niche in the business." The goal was to charge fares at all times that were below the cost of driving an automobile from one Texas city to another. (Later, in most of the airports in which Southwest initiated service, traffic on the routes it served increased three or four times. Over the years, Southwest enjoyed a long waiting list of airport managers seeking out the airline to initiate service to their airports.) Management had to sell one of its four planes at a profit to survive the first year. This led to another key element of Southwest's eventual strategy, the 10-minute turnaround. In order to operate with three planes rather than four, it became even more necessary to get maximum utilization out of the fleet. As a result, Southwest made efforts to reduce the turnaround time (from arrival at the gate to push-back from the gate) to 10 minutes, barely one-fifth that of competitors. While average turnaround time increased over the years due to more seats (typically 130 per plane), higher load factors (seats filled per available seats), and the carriage of freight, it remained less than 30 minutes, about half the industry average in North America.? Southwest's business model, as it quickly evolved, became well known for its contrarian approach to air transportation, what it didn't provide that other carriers did. Because its flights were typically 90 minutes or less, it served no food (other than peanuts). There was no first class, no assigned seats, no interlining (with other airlines) of bags or passengers, no code sharing (with other airlines' flights to extend routes), and no use of the popular hub-and-spoke route structure. Instead, Southwest offered low fares, frequent flights, on-time arrivals, and point-to-point service, often from airports not served by other airlines, some of which were less congested and more easily accessible to business travelers. Its strategy was fueled by the low fares that it made possible. Southwest executives regarded the private automobile, not other airlines, as its competitor. They set fare levels accordingly. 2 The savings provided by fast turnaround yielded significant competitive advantage for Southwest by increasing the utilization of its 537 planes, each of which flew on average between five and six flight segments during a typical 11-hour day. At the time of the case, Boeing was quoting to potential buyers a price of about $60 million for a single 737-300 plane. The Focus on People and the Culture Frequent on-time service to and from convenient airports for business travelers, provided at fares rivaling the costs of driving an auto, were only some of the elements Southwest sought to deliver to Customers. Just as important was the service provided. The founders wanted the service to be both memorable and inexpensive to deliver. They had enlisted the help of a regional advertising agency, The Bloom Agency, to come up with, among other things, a personality for the airline. As a result, Southwest became the airline that made it fun to fly. Young, friendly, refreshing, and exciting. Thus, the LUV (later, Southwest's stock designation on the New York Stock Exchange) airline was born, featuring things that today might be regarded as blatantly sexist: love potions (for drinks), the love machine (for tickets), and ads with female cabin attendants in hot pants who invited travelers to fly an airline that provided something only Southwest could offer, me." From the outset, Southwest's management focused on hiring agents and cabin staff with positive personalities, senses of humor, and the willingness to make humorous intercom announcements and otherwise innovate on behalf of Customers. These antics replaced meal service on flights that were relatively short anyway. Employees had to be able to use good judgment in implementing Southwest's policy of do whatever you feel reasonable doing for a Customer. In return, the company paid wages that were roughly standard for a start-up carrier and gave Employees an opportunity to participate in the airline's success through membership in its profit-sharing and stock ownership programs. The organization was imbued with a sense of ownership. Jeff Lamb, Senior Vice President Administration and Chief People Officer, told a story that illustrated it. He had just joined the organization, leaving his former job in real estate because he was intrigued by the chance to be part of the Southwest experience, when a member of his staff came by the office to drop off a cowbell and announce that "everybody is gathering in the lobby in 15 minutes to welcome Bob back from the hospital." Lamb said, I didn't get the memo." The reply was, We don't send memos for this sort of thing. See you there." According to Lamb, hundreds of people assembled in the lobby, greeted Bob, and were back at work as if nothing had happened, all in the space of 15 minutes, while a skeleton staff maintained" coverage to ensure that nothing stopped entirely. A Culture Committee," drawn from all levels of the organization, reviewed Employee ideas for recognition and celebration, and used the Southwest Way to guide its efforts. (See Exhibit 1 for Southwest's mission and values.) Many of the projects were self-funded, with Employees raising money to buy T-shirts and other paraphernalia with bake sales and other events. Employees extended their team efforts when away from the job as well, engaging in community-based activities together. The organization as a whole officially supported the Ronald McDonald House Charities for sick children and their families. There was a constant effort to maintain what came to be known as a "Warrior Spirit" at Southwest. A typical, strongly worded memo from Herb Kelleher encouraging everyone to reduce costs to maintain the airline's low-cost leadership position was intended, in the words of the memo, to make sure we don't "rest on our laurels and get a thorn in our ass." A "Servant's Heart and a "Fun-LUVing Attitude characterized much of the airline's culture, as shown in Exhibit 1. Cofounder Kelleher, who had become Chairman in 1978 and CEO in 1981, and Barrett, who for many years served as Executive Vice President Customers and, later, President, led efforts to preserve the culture. Kelleher's antics were legendary. They included dressing in outlandish costumes; riding a motorcycle into the headquarters lobby; arm-wrestling another airline executive in a highly publicized "Malice in Dallas" match over the rights to the use of an advertising slogan, "Just Plane Smart"; and serving as the lead celebrant at the many awards parties that Southwest Employees held. Visitors to Southwest's headquarters were impressed by the thousands of photos of Employees taken at these events, as well as frequent hugging and use of the word LUV." As one visitor put it," the longer it went on the longer I concluded that the behavior was real. No one could keep up a pretense for that long." Southwest remained the most heavily unionized airline in the industry. Both national unions such as the International Association of Machinists and "associations, such as the one formed by the Pilots, represented its Employees. In its negotiations with these organizations, management had always sought to provide reasonable compensation and secure flexible work rules. The flexible work rules enabled Employees to perform many different jobs as members of teams. For example, Pilots could handle baggage if the situation demanded it. Teams were assigned to gate operations, with responsibility for turning planes around rapidly. If a plane was delayed on the ground, it was the team's responsibility to make sure it didn't happen again. As a result, Southwest heavily emphasized the selection of Employees with abilities to relate to both Customers and other Employees. Regardless of rank, they were then required to complete team-based training activities. By 2007, Lamb's People Department was responsible for hiring roughly 4,000 people per year in an organization of more than 35,000. This was sufficient to support growth and replace departures in an organization with a relatively low Employee turnover rate of less than 5%. That year, it received 329,000 applications for employment. A significant number of hires were from current Employees' referrals. Recognized by Fortune magazine as one of the best places to work in the U.S. for several years running, Barrett discontinued Southwest's participation, declaring that it required too much of an investment in time. Leadership and Succession Former CFO Kelly became CEO in 2004, with attendant responsibilities for maintaining the organization's momentum. He added President and Chairman to his title in 2008. Among other things, he had been credited with instituting a very successful fuel hedging strategy (described below) that had saved Southwest more than $4 billion between 2000 and 2008 and further differentiated the airline's financial performance from its competitors. Chairman Kelleher and President Barrett retired in 2008. The Board, to reward their legendary service, named both to Emeritus status, with rights to maintain their offices at headquarters for five years. They appeared frequently at Employee gatherings. Kelly appeared to be sanguine about the prospect of having two giants of the industry in close proximity, if not looking over his shoulder. Controlled Growth Southwest saw its revenue grow from $5.9 million in 1972 to $5.7 billion in 2000, a compound growth rate of more than 25%. By the late 1990s, however, the airline sought a controlled growth rate of about 8% to 10% per year in order to make it possible to hire enough of the right people to preserve Southwest's service, personality, and culture. Southwest was the only airline ever to win the triple crown" of service, recording the highest levels of Customer Satisfaction, the best on-time arrival record, and the lowest level of lost baggage. Further, it accomplished the feat in five consecutive years between 1992 and 1996. (See Exhibits 2 and 3 for the airline's financials and operating data for selected years.) The Company rewarded Employees for this achievement with a specially painted aircraft, called "Triple Crown One," that included the names of all Employees at the time on the overhead bins. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, posed challenges for Southwest as well as other airlines. But unlike its competitors, Southwest's management did not furlough anyone. Nevertheless, new security rules for boarding passengers threatened to slow a process particularly important to an airline operating with a significant percentage of last-minute "walk up" passengers and short turnaround times. As a result of management's decision to maintain its flight schedule and staff, Southwest's revenues declined less than 2% in 2001 compared to the previous year. It emerged from the September 11 crisis in a competitively stronger position than before, with by far the highest-valued stock of any U.S. airline. Transforming the Core Strategy Opportunities for future growth within the highly focused strategy centered around low fares and point-to-point flights were less certain. Kelly summarized the challenges this way: One challenge in particular is overarching: a more than 35% rise in operating costs since 2005 caused simply by increased energy costs. For years, we had stable costs, low fares, and traffic stimulation. Now, higher costs mean higher fares, which mean traffic de-stimulation, which means less capacity needed, etc. One way or the other, for legacy carriers to survive, they had to get their costs (and their fares) down. Demand was soft and the legacies' days of living off fat, high fares were over. Those sensing the opportunity formed a new generation of low-cost/low-fare carriers. Now, our legacy competitors (through bankruptcy) and new entrant low-cost carriers have lower labor rates than ours. Better, sophisticated revenue management and customer fare shopping via the Internet make it easier for legacy airlines to compete. This represents a threat to our market niche. We know we have to adjust to this looming competitive reality. Also, it's a new world with security. We have to transform our business model and expand our revenue-generating capabilities. To do that, we have to transform or even construct our capabilities to offer new products and services. Changing the Customer Experience As a result, management set out to increase revenue without raising fares and damaging its cherished low-fare brand. To do this, it sought to win more Customers by improving the Southwest Customer Experience. This meant adding flights among cities the airline currently served, expanding routes to meet Customer needs for service to important U.S. destinations, adding code-share destinations (outside the U.S.), and adding more sophisticated route scheduling and revenue management of seat inventories and fares. It also meant completely transforming the supporting technology and challenging decades old paradigms, like open versus assigned seating, as well as introducing an array of new fares, products, onboard services, and a bags fly free" policy. Adding Flights In 1984, Southwest added its first flight segment of more than three hours. Until then, it had assumed that service with minimal onboard catering (snacks and beverages) was not suitable for longer flights. But the new service between, for example, Los Angeles and Houston proved to be popular. Further, Customer Service scores on the flights dropped very little as Southwest's low fares and Customer- oriented, fun Employees (who were known for initiating games such as "who's got the biggest hole in your sock contest") outweighed other service factors. By the fall of 2008, with the addition of new stations further and further east, the proportion of Southwest's flights greater than 1,200 miles in length had risen to approximately 25%. Popular routes, for example, were those between Phoenix and St. Louis, Chicago/Midway and Las Vegas, and Denver and Orlando. Aside from more flights to more distant locations, there were many opportunities to add shorter flights to schedules connecting existing stations in the network. New Markets Southwest first extended its route structure to the northeast U.S. in 1993 with the initiation of service to Baltimore. (Exhibit 4 shows the list of cities Southwest served throughout its history.) Many questioned whether the airline would be able maintain its culture of enthusiastic, fun-loving, Customer-oriented Employees working in teams both on the job and in community activities after work. Pete McGlade, Vice President Schedule Planning, stressed that Southwest would pass over a city if it could not retain the airline's LUV" culture by operating there. As he put it in 2002, [e]very schedule decision we make must be consistent with our strategy. Our Employees need to internalize the strategy, and consistency is necessary to ensure that everyone understands the scheduling decisions."4 With care in hiring, combined with the transfer of Southwest veterans from elsewhere in the system to Baltimore for short- or long-term assignments, the company found it could transport the Southwest culture even to the East Coast. It helped that Baltimore's airport was not congested and that the community welcomed the new service. As a result, Southwest continued its advance northeastward, successfully introducing service to Long Island through Islip airport and to the Boston area through airports in Providence, Rhode Island, and Manchester, New Hampshire, all uncongested While Southwest made these moves to fuel its continued growth, it needed to make other moves to counter new competitors that attempted to emulate the airline's fare structure and operating strategy, making both less distinctive. Fare and service differences between Southwest and competitors declined substantially after 2005. With higher load factors, average turnaround times for Southwest's aircraft had increased to approximately 25 minutes (as opposed to an average of about 60 minutes for the U.S. airline industry). And, after 2007, average daily aircraft utilization of more than 11 hours of operating time per day was declining, as airlines trimmed unprofitable flights from the schedule. CEO Kelly had begun to emphasize the power of the network. It allows us to go into a market with just a few flights to benefit the network. I call it playing 'small ball.'" He cited a possible move into Minneapolis as an example. It involved a new service in competition with Delta, the dominant carrier out of that station, to only one other location, Chicago's Midway airport. It would allow Southwest's Chicago passengers book into Minneapolis. Other Customers could also do so if they were willing to fly through Midway. 4 See James L. Heskett, "Southwest Airlines, 2002: An Industry Under Siege," HBS No. 803-133 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2003). Customer Service scores on the flights dropped very little as Southwest's low fares and Customer- oriented, fun Employees (who were known for initiating games such as "who's got the biggest hole in your sock contest") outweighed other service factors. By the fall of 2008, with the addition of new stations further and further east, the proportion of Southwest's flights greater than 1,200 miles in length had risen to approximately 25%. Popular routes, for example, were those between Phoenix and St. Louis, Chicago/Midway and Las Vegas, and Denver and Orlando. Aside from more flights to more distant locations, there were many opportunities to add shorter flights to schedules connecting existing stations in the network. New Markets Southwest first extended its route structure to the northeast U.S. in 1993 with the initiation of service to Baltimore. (Exhibit 4 shows the list of cities Southwest served throughout its history.) Many questioned whether the airline would be able maintain its culture of enthusiastic, fun-loving, Customer-oriented Employees working in teams both on the job and in community activities after work. Pete McGlade, Vice President Schedule Planning, stressed that Southwest would pass over a city if it could not retain the airline's LUV" culture by operating there. As he put it in 2002, [e]very schedule decision we make must be consistent with our strategy. Our Employees need to internalize the strategy, and consistency is necessary to ensure that everyone understands the scheduling decisions."4 With care in hiring, combined with the transfer of Southwest veterans from elsewhere in the system to Baltimore for short- or long-term assignments, the company found it could transport the Southwest culture even to the East Coast. It helped that Baltimore's airport was not congested and that the community welcomed the new service. As a result, Southwest continued its advance northeastward, successfully introducing service to Long Island through Islip airport and to the Boston area through airports in Providence, Rhode Island, and Manchester, New Hampshire, all uncongested While Southwest made these moves to fuel its continued growth, it needed to make other moves to counter new competitors that attempted to emulate the airline's fare structure and operating strategy, making both less distinctive. Fare and service differences between Southwest and competitors declined substantially after 2005. With higher load factors, average turnaround times for Southwest's aircraft had increased to approximately 25 minutes (as opposed to an average of about 60 minutes for the U.S. airline industry). And, after 2007, average daily aircraft utilization of more than 11 hours of operating time per day was declining, as airlines trimmed unprofitable flights from the schedule. CEO Kelly had begun to emphasize the power of the network. It allows us to go into a market with just a few flights to benefit the network. I call it playing 'small ball.'" He cited a possible move into Minneapolis as an example. It involved a new service in competition with Delta, the dominant carrier out of that station, to only one other location, Chicago's Midway airport. It would allow Southwest's Chicago passengers book into Minneapolis. Other Customers could also do so if they were willing to fly through Midway. 4 See James L. Heskett, "Southwest Airlines, 2002: An Industry Under Siege," HBS No. 803-133 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2003). Code-Sharing Agreements In 2004, a strategic opportunity to grow in Chicago presented itself. ATA Airlines filed for bankruptcy. In addition to buying certain airport assets at Chicago Midway, Southwest agreed to code share with ATA for the first time in Company history.5 The service began in February 2005 for code-share service to multiple domestic destinations, including New York LaGuardia and Hawaii. In April 2008, ATA ceased scheduled service, and the code-share agreement with it ended. The ATA code share was a success, generating nearly $40 million in additional revenue in 2007. So with the potential for substantial growth to near- international markets and work underway to develop new technology to accommodate code sharing, Southwest began to actively pursue other airline partnership opportunities. In July 2008, Southwest announced a Memo of Understanding with WestJet, a Canadian carrier with an award-winning corporate culture. It was in the process of finalizing a similar Memo of Understanding with Volaris for code-share flights to Mexico. Volaris was known for its competitive pricing and a reputation as Mexico's most on-time airline. Developing Supporting Technology By 2002, Southwest's management knew that it had to, in Kelly's words, "take the airline product up a notch, to remain unique and still inspire Customers. To do this, it knew that it had to have new systems and processes that would enable it to change both the network and various operating practices. As one example, the existing system would not allow management to schedule and pay a cabin crew of more than three people. So it was impossible, without technology changes, to consider flying planes larger than 150 passenger seats (something the airline at the time of the case was not actively considering). Similarly, in 2002, the system would not accommodate code sharing with other airlines, thereby ruling out that strategic move. By 2008, systems were in place or in development that would allow management to examine a wide range of strategic initiatives, such as the impact of new routes and changes in operating procedures, like the boarding process. Challenging Old Paradigms: The Boarding Process One strategic question was whether Southwest should change its boarding procedure. Since the early 1970s, Southwest had boarded its flights on a first-come, first-served basis, with no assigned seats. In those days, load factors were light, and there was little need for assigned seating. Customers had to stand in three lines, representing the groups of Customers that would board sequentially. The process fostered quick boarding, as Customers hurried to get into their preferred seats. But some Customers, particularly those not used to the system, regarded it as annoying, because they had to arrive early and stand in line. They judged it as inferior to other airlines' practices of allowing passengers to reserve seats. In the words of one Southwest executive, the Marketing Department "was not proud about" the boarding process and felt that the company could improve it. But there was a fear of change. Southwest's objective was to improve the boarding process in the Customers' minds, at the same or lower costs. It organized an experiment in 2007 in San Diego. It allowed passengers to reserve seats 5 Code sharing was a practice in which a flight operated by an airline was jointly marketed as a flight for one or more other airlines. The main benefit of code sharing was that it allowed carriers to sell tickets on routes they did not fly. To travelers, the main benefit was the ability to buy "through tickets" on convenient, published itineraries. Without a code-share agreement in place, travelers would have to purchase two separate, and probably more expensive, individual tickets. Code sharing allowed Southwest Airlines to fill seats that would otherwise have been empty. in advance. It filmed the actual boarding processes and then asked passengers several questions about their experience. It found that veteran Southwest Customers, in particular, were not enthusiastic about the change. Some said, for example, that they didn't mind getting to the airport in time to get the best seat choices. What they were really concerned about was chaos at the gate. Others were more concerned about being able to choose who they sat next to than where they sat. After extensive Customer research, Southwest found that Customers preferred its open seating by two to one. Of equal significance was that assigned seats, which removed the incentive to board quickly, slowed the boarding process by four to six minutes. As a result of the experiment, perhaps the most important that the airline had ever undertaken, management decided to maintain open seating. But it began allowing Customers to reserve" places in the waiting line so that they no longer needed to arrive at the gate early or stand in line to get preferred boarding treatment. This new boarding procedure, launched in November 2007, paved the way for a priority boarding product called Business Select," something Southwest had never offered, for a slight premium above the carrier's full fares. New Fares, Products, Services, and Policies Other efforts to transform the Customer experience involved changes in fares, products, services, and policies. For example, in addition to instituting a Business Select program to provide greater convenience to business flyers, Southwest began offering Early Bird fares to those booking early (enabling Southwest to continue emphasizing low fares in its advertising), and altered the Rapid Rewards (frequent flyer) program to make it quicker to earn free flights. Management was considering new services such as onboard Internet and a "cashless (credit cards only] cabin" for onboard purchases. It decided not to charge fees for changing tickets. But perhaps the policy receiving the most attention from Customers, in view of other airlines' growing charges for checked luggage, was Southwest's bags fly free" policy, which allowed passengers to check up to two bags at no cost. It was clear that with mounting competition, the number of innovations required to differentiate Southwest's service offering would only grow. It was important that the public view these as consistent with Southwest's low-fare, high-service image. Cost Management: Fuel Hedging Southwest's finance department had been hedging fuel prices for decades. The practice helped the airline accomplish several financial objectives: 1. Plan toward profitability. Hedging reduced the risk that Southwest's fuel expenses would swing wildly out of control. Hedging was like a form of insurance against volatile swings and rising energy costs that threatened profitability. 2. Plan cash flows. Hedging helped the company plan cash flows more accurately, in order to have enough cash in the bank to cover bills and maintain liquidity. 3. Lower overall fuel expenses. Hedging helped Southwest acquire jet fuel at lower prices. Since fuel was such a huge expense for Southwest - actually one of the largest components of its cost structure- it made sense to guard against the possibility of catastrophic fuel price increases. Southwest was among the first in the industry to hedge the majority of its fuel. Even more surpris- ing, it continued to be the leader among U.S. airlines in the practice for years, even as Southwest's successful relative performance became more and more noticeable. (See Exhibit 5 for the size and economic impact of Southwest's fuel hedging on its financial performance for 2006 and 2007.) The Philadelphia Story In 2004, Southwest saw an opportunity to institute service to one of US Air's hubs, in Philadelphia. It predicated its decision to enter Philadelphia on two primary considerations. One, Philadelphia was the largest market served by only one airport (as opposed to being divided among a few airports). Two, travelers in the Philadelphia market were displeased with the higher fares and poor customer service that US Air provided. The move attracted attention because it was clear from the start that Southwest intended to establish extensive service between Philadelphia, an airport with greater congestion and more frequent delays than any out of which it had operated to date, and several other cities. Many observers assumed that the move, unlike some others that Southwest had made, was intended to divert significant amounts of traffic from US Air, if not drive it out of its Philadelphia hub altogether. Instead of acquiring permission to operate out of two or three gates, Southwest occupied eight, with a capacity of at least 80 flights. But after its merger with America West, US Air was able to stabilize its financial performance sufficiently to maintain a significant presence in Philadelphia. By late 2008, Southwest had grown aggressively to 65 flights daily out of its Philadelphia station. (See Exhibit 6a for Philadelphia's operating statistics.) However, with high fuel prices and the economy in recession, it put further plans for growth in Philadelphia on hold. Philadelphia posed an operating challenge. As Mike Van de Ven, Executive Vice President and Chief Operating Officer, put it, We seem to operate either on time or with three-hour delays. But we're getting better at sequencing our flights. Our teams work closely with air traffic control. And we will impose our own traffic flow delay program if the conditions warrant, so our planes will wait on the ground rather than in the air." The La Guardia Decision With ATA Airlines Inc. ceasing operations in April 2008, its 16 LaGuardia time slots would become available, prompting Kelly to initiate analyses to guide Southwest's management in deciding whether or not to bid for the slots. Given a winning bid, LaGuardia would become the first airport with a practice of slotting flights that Southwest served. This would require negotiating with the Port Authority of New York. Each time slot would allow for an arrival or departure within a 30-minute window during the day. But once the airline agreed on the times, it could trade specific slots with other airlines operating out of LaGuardia to create a logical schedule. As the discussion continued around the table in Kelly's office, those arguing for the acquisition pointed out the need for continued growth, both for financial reasons and for the health of the Southwest organization, as well as the need for service to New York that Southwest's operations out of Islip airport, some 30 miles from the city, did not currently meet. They also emphasized the benefits to route network traffic that service to LaGuardia would provide. Supporters argued that if Southwest could get the slots for the relatively small investment represented by the recommended bid of $7.5 million, it could generate enough revenue from eight flights daily to cover costs, merely by spending a little money to promote the LaGuardia service to Southwest Customers in cities the airline currently served. Some expressed concerns about the further departure from Southwest's original strategy of operating out of non-congested, low-cost airports that a LaGuardia service would represent. While not necessarily disagreeing with a decision to go, Bob Montgomery, Vice President of Properties, pointed out that 50% of all delays in the U.S. are driven by delays experienced in the three major New York airports." Others raised questions about LaGuardia's high cost structure (including costs resulting from flight delays, high landing fees, and high wages) as well as the potential threats to Southwest's culture and its reputation for good Customer Service that a LaGuardia operation posed. Several expressed concerns about the challenges of operating out of LaGuardia, with its frequent flight delays and high cost structure. On the other hand, Daryl Krause, Senior Vice President Customer Services, believed that long-termers at the high end of the wage scale might be more interested in bidding into a job at LaGuardia, at least for 6 to 12 months, just because they've always wanted to experience New York." Landing costs alone at LaGuardia would be significantly higher than those Southwest incurred at Islip airport. (See Exhibit 6b for data comparing LaGuardia's operating record and economics with those of other major airports.) Supporters of the move countered that the service would represent only seven or eight flights out of the roughly 3,200 the airline operated and that Southwest had learned how to operate out of "difficult" terminals when it moved into Philadelphia in 2004. Some raised questions about whether the Philadelphia experience was even relevant to LaGuardia. In Philadelphia, Southwest had made a major commitment to establish competitive dominance, potentially creating some operating stress on the rest of the Southwest network. As Montgomery put it, "if LaGuardia is served from only one or two other cities, we can effectively isolate the operation by shuttling planes between those cities and LaGuardia and make sure that problems don't flow through the network." Kelly was determined to push toward a decision by the end of October. It was only the first step in a process that could take months. First, Southwest would have to bid on ATA's operating certificate, which included access to the slots. It was not clear whether there were other potential bidders, and there was no assurance that $7.5 million would be a winning bid. The bankruptcy process and the disposition of ATA's assets were not expected to be completed before March 2009. At that point, a team led by Montgomery would have to complete negotiations with airport management for the specific gate to be used and with the Port of New York Authority for the time slots. With a successful bid, Southwest could be serving LaGuardia by the end of 2009. But it had to make the decision in the context of increasing competition for Southwest's low-cost, low-fare position; higher fuel costs; uncertain demand; and changing Customer needs and their use of information technologies. Available capacity did not seem to be an issue. At the time, Southwest was operating 537 planes, more than 20 of which typically were not eligible for scheduled flying due to routine scheduled maintenance. In addition, Southwest had 13 new Boeing 737 aircraft due for delivery in 2009 that it could fly, retire, sublease, or use as a cushion to maintain capacity, while accelerating maintenance on the rest of the fleet. High fuel costs had changed the cost structure from one dominated by fixed costs to one driven by variable costs, in which it was sometimes more economical to park an aircraft than operate it. In response, Southwest was adjusting to a higher cost structure by aggressively optimizing its network in an effort to minimize the underutilization of aircraft and maximize route profitability. This was typical of efforts all airlines were making to retrench to accommodate the volatile fuel market and possible declines in demand resulting from what could be a prolonged global recession. Exhibit 1 Southwest Airlines Mission and Values Mission The mission of Southwest Airlines is dedication to the highest quality of Customer Service delivered with a sense of warmth, friendliness, individual pride, and Company Spirit. The Southwest Way Warrior Spirit: Work hard Desire to be the best Be courageous Display a sense of urgency Persevere Innovate Servant's Heart: Follow the Golden Rule Adhere to the Basic Principles* Treat others with respect Put others first Be egalitarian Demonstrate proactive Customer Service Embrace the SWA Family Fun-LUVing Attitude: Have FUN Don't take yourself too seriously Maintain perspective (balance) Celebrate successes Enjoy your work Be a passionate Teamplayer *The basic principles are: (1) Focus on the situation, issue, or behavior, not on the person, (2) Maintain the self-confidence and self-esteem of others, (3) Maintain constructive relationships with your Employees, peers, and Managers, (4) Take initiative to make things better, and (5) Lead by example. Source: Adapted from the Company's website, Southwest.com, accessed February 2010. Exhibit 2 Southwest Airlines Performance, Selected Years (1999-2007) 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 4,736 5,555 5,937 7,584 9,851 2.224 Operating revenue (in $ millions) Operating expenses: Salaries, wages, and benefits Fuel and oila Depreciation and amortization Other 1,455 492 249 1,856 771 318 830 2.702 1,342 469 3,213 2,690 555 384 2,016 1.858 1,979 2,251 2,612 3,954 4,924 5,454 6,764 9,070 782 631 483 820 791 54 70 122 119 (56) 10 (64) (203) 91 (57) (259) (86) (90) (94) (292) 8 (225) 708 266 (54) 874 774 299 (267) 1,058 413 475 442 645 Total operating expenses Operating income Other expenses (income): Interest expense Capitalized interest/interest income Other (gains) and lossesa Total other expenses (income) Income (loss) before income taxes Provision (benefit) for income taxes Net income Revenue passengers carried (000's) Revenue passenger miles (millions) Available seat miles (millions) Passenger load factor Average stage length (miles) Passenger-revenue yield per RPM Operating revenue yield per ASM Operating expenses per ASM Size of fleet at year end Full-time equivalent employees (year-end) 57,500 36,479 52,855 69.0% 465 12.51c 8.96 (197) 828 317 511 64,446 44,494 65,295 68.1% 514 65,674 47,943 71,790 66.8% 558 326 548 77,694 60,223 85,173 70.7% 607 88,713 72,319 99,636 72.6% 629 12.09 13.080 11.97 8.270 8.510 12.09 8.90 7.94 9.90 7.48 7.540 7.60 9.100 520 355 388 312 27,653 445 31,729 31,580 32,847 34,378 Source Southwest Airlines Annual Reports for selected years. Including accounting effects of fuel hedging, as shown in Exhibit 4. Exhibit 3 Southwest Airlines Performance, Selected Years (1999-2007) 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 Selected Balance Sheet Items $419 $2,280 Current assets (in $ millions): Cash and cash equivalents Accounts and other receivables Fuel hedge contracts Other current assets 73 71 $1,865 132 164 152 $2,280 258 641 $2,213 279 1,069 882 139 169 441 631 2,520 8,902 2,313 10,550 3,620 12,915 4,443 15,160 6,849 Total current assets Property and equipment at costa Less allowance for depreciation and amortization 1,841 2,456 3,107 3.488 4,286 5,008 6,445 7,443 9,427 Net property and equipment Other assets 10,874 1,455 13 31 122 1,171 Total assets 5,652 8,997 9,878 14.218 16,772 157 504 405 524 Current liabilities (in $ millions): Accounts payable Accrued liabilities Other liabilities 535 548 650 668 2,074 1.250 759 3,107 972 268 1,187 960 2.239 1.723 4,838 3,848 1,394 872 1.332 2,050 Total current liabilities Long-term debt less current liabilities Deferred income taxes Other long-term liabilities 1,327 1,058 1,896 2,535 692 292 1,420 351 539 405 408 Total liabilities Stockholders' equity 1,856 2,836 2,744 4,014 3,103 5,052 7,543 6,675 4,993 6,941 Total liabilities 5,651 8,997 9,878 14,218 16,772 5.9% 4.0% 3.8% Consolidated financial ratios: Return on average total assets Return on average stockholders' equity Operating margin Net margin 8.8% 17.3% 15.5% 9.4% 12.4% 9.7% 8.1% 7.9% 6.4% 6.3% 7.9% 9.6% 6.4% 4.3% 9.6% 8.0% 6.5% Source: Southwest Airlines Annual Reports and 10-K statements. Data for property and equipment for 2007 include $13,019 million for equipment. bIncluding frequent flyer program liabilities. Exhibit 4 Markets Served by Southwest Airlines, 1971-2008 Year # of Markets Markets 1971 3 1 5 1975 1977 1978 1979 1980 1 1 4 1982 6 1984 1 3 1985 1986 1 1987 2 1988 1 2 Dallas, Houston (Hobby), San Antonio Harlingen Corpus Christi, Midland, Lubbock, El Paso, Austin Amarillo New Orleans Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Albuquerque, Houston Intercontinental Las Vegas, Phoenix, San Diego, Kansas City, Los Angeles, San Francisco Little Rock Chicago (Midway), St. Louis, Ontario Nashville Birmingham, Detroit Metro Detroit City Indianapolis, Oakland Burbank, Reno Sacramento Cleveland, Columbus Louisville, San Jose, Baltimore (closed Detroit City) Orange County, Portland, Seattle, Spokane, Boise, Tucson, Salt Lake City, Omaha (acquired Morris Air) Omaha Orlando, Tampa Bay, Ft. Lauderdale, Providence Jacksonville, Jackson Manchester Islip, Raleigh-Durham, Hartford Albany Norfolk 1989 1990 1991 1992 2 1 2 3 1993 1994 7 1 4 2 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 1 3 1 2001 1 0 o 2002 2003 2004 2005 1 2 Philadelphia Pittsburgh, Ft. Myers (Began Code Sharing with ATA) Denver, Washington Dulles San Francisco 2 2006 2007 2008 1 0 Source: Southwest Airlines Annual Reports. Exhibit 5 Accounting for Fuel Hedge Contracts, Southwest Airlines (2006 and 2007) All cash flows associated with purchasing and selling derivatives are classified as operating cash flows in the Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows. The following table presents the location of pre- tax gains and/or losses on derivative instruments within the Consolidated Statement of Income. 2006 (in millions) 2007 (in millions) Fuel hedge (gains) Included in fuel and oil expense $(634) $(686) Market-to-market impact From fuel contracts settling in future periodsincluded in other (gains) losses, net 42 (219) Ineffectiveness from fuel hedges settling in future periodsincluded in other (gains) losses, net 39 (51) Realized ineffectiveness and mark-to-market (gains) or lossesincluded in other (gains) losses, net 20 (90) Premium cost of fuel contracts included in other (gains) losses, net 52 58 Also, the following table presents the fair values of the Company's remaining derivative instruments, receivable amounts from settled/expired derivative contracts, and the amounts of unrealized gains, net of tax, in "accumulated other comprehensive income (loss)" related to fuel hedges within the Consolidated Balance Sheet. 2007 (in millions) $1,069 1,318 Fair value of current fuel contracts-accrued liabilities/ fuel derivative contracts). Fair value of noncurrent fuel contracts (other deferred liabilities) other assets .......... Due (to) from third parties for settled fuel contracts-accrued liabilities/ accounts and other receivables). Net unrealized (losses) gains from fuel hedges, net tax-accumulated other comprehensive income (loss) 109 1,220 Source: Southwest Airlines 10-K reports. Exhibit 6a Operating Statistics, Domestic Flights, Philadelphia International Airport (2003-2008) 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Ranka % of flights on-time Departures Arrivals 74% 77% 72% 72% 69% 70% 73% 23 27 78% 74% 67% Average delay (minutes) Departure Arrivals 56.2 56.4 56.3 59.1 57.2 57.3 60.7 59.2 65.2 62.9 27 26 % of flights canceled 2.34% 2.58% 1.79% 2.39% 1.96% 23 Number of flights (000) 121.7 126.4 108.3 104.1 100.5 Carrier share of traffic US Airways Southwest Wisconsin American United Other 37.3% 12.1 11.0 5.4 5.0 29.2 34.2% 13.7 9.6 5.2 4.7 32.8 34.8% 14.5 9.5 4.7 4.2 32.3 Exhibit 6b Operating Statistics, Domestic Flights, New York City La Guardia Airport (2004-2008) 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Ranka % of flights on-time Departures Arrivals 82% 78% 67% 75% 64% 75% 71% 58% 25 30 73% 63% Average delay (minutes) Departure Arrivals 58.3 56.6 59.8 57.9 59.2 57.8 61.0 58.8 63.6 60.5 26 23 % of flights canceled 3.41% 3.97% 3.70% 5.21% 4,83% 31 Number of flights (000) 127.5 127.5 127.5 123.0 119.1 Carrier share of traffic American Delta US Airways Northwest United Other 20.5% 17.7 9.4 7.2 6.3 39.0 20.6% 15.7 9.5 7.2 6.3 40.6 20.1% 16.2 8.7 7.1 7.0 40.9 Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, website, http://www.transtats.bts.gov/airports.asp?pn=1, accessed August 2009. a Rank among 31 largest U.S. airports; 1 is best. ba flight is considered delayed when it arrives or departs 15 or more minutes behind schedule. Delayed minutes are calculated from delayed flights only