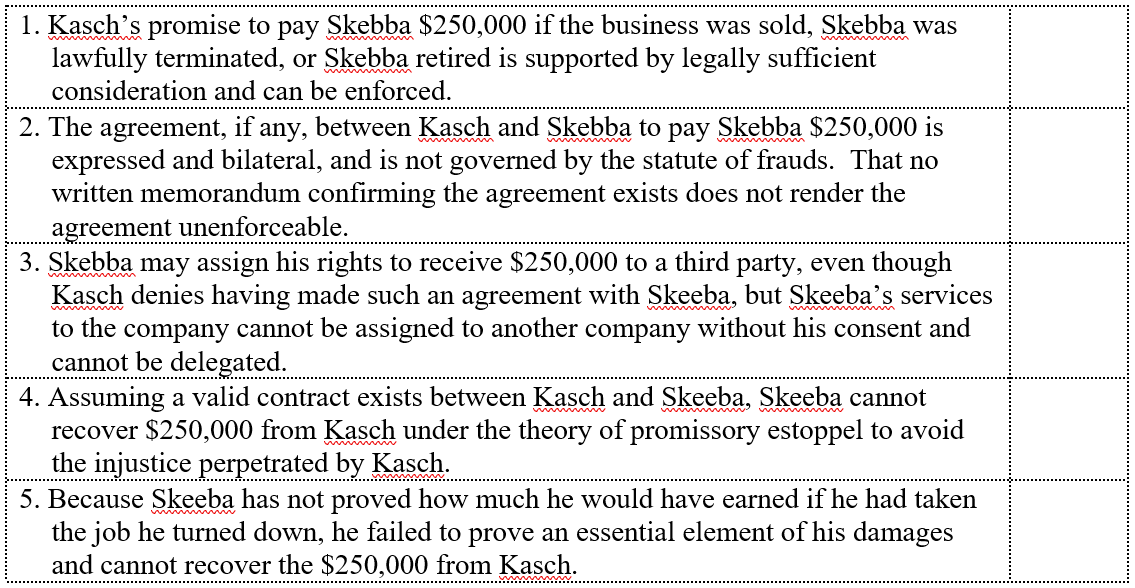

Question

Jeffrey Kasch, with his brother, owned M.W. Kasch Co.Kasch hired William Skebba as a sales representative. Over the years, Kasch promoted Skebba to account manager,

Jeffrey Kasch, with his brother, owned M.W. Kasch Co.Kasch hired William Skebba as a sales representative. Over the years, Kasch promoted Skebba to account manager, then to customer service manager, field sales manager, vice president of sales, senior vice president of sales and purchasing, and finally to vice president of sales. When M.W. Kasch Co. experienced serious financial problems in 1993, another company solicited Skebba to leave Kasch and work for it.When Skebba told Kasch he was accepting the new opportunity, Kasch asked what it would take to get him to stay, and noted that Skebba's leaving at this time would be viewed very negatively within the industry. Shortly thereafter, Skebba told Kasch that he needed security for his retirement and family and would stay if Kasch agreed to pay Skebba $250,000 if one of these three conditions occurred: (1) the company was sold; (2) Skebba was lawfully terminated; or (3) Skebba retired. Kasch agreed to this proposal and Kasch promised to have the agreement drawn up. Skebba turned down the job opportunity and stayed with Kasch from December 1993 (when this discussion occurred) through 1999 when the company assets were sold.

Over the years, Skebba repeatedly asked Kasch for a written summary of this agreement; however, none was forthcoming. Eventually, Kasch sold the business. Kasch received $5.1 million dollars for his 51 percent share of the business when it was sold. Upon the sale of the business, Skebba asked Kasch for the $250,000 Kasch had previously promised to him, but Kasch refused, and denied ever having made such an agreement. Skebba sued Kasch, alleging breach of contract and promissory estoppel.

The case went to trial. The jury found there was no contract, but that Kasch had made a promise upon which Skebba relied to his detriment, that the reliance was foreseeable, and that Skebba was damaged in the amount of $250,000. The trial court ruled against Skebba, however, on the ground that applicable case law did not allow the court to order Kasch to pay the sum that he had promised. Instead, it took the position that Skebba had not proved his damages because he had not proved how much he would have earned if he had taken the job that he turned down. Skebba appealed.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started