Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Lean as a Universal Model of Excellence: It Is Not Just a Manufacturing Tool! Lean is a systematic way to enhance value delivery, whatever

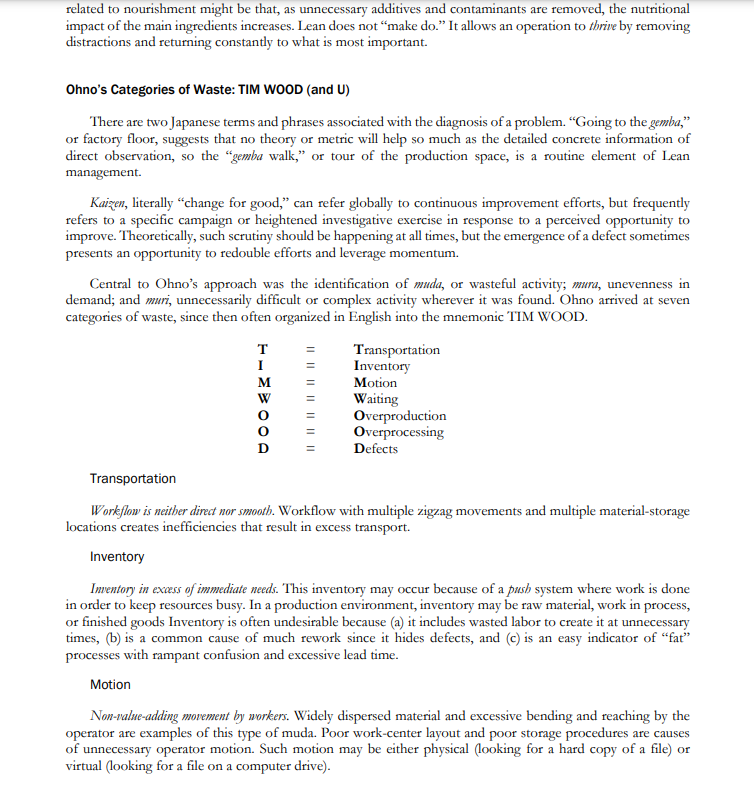

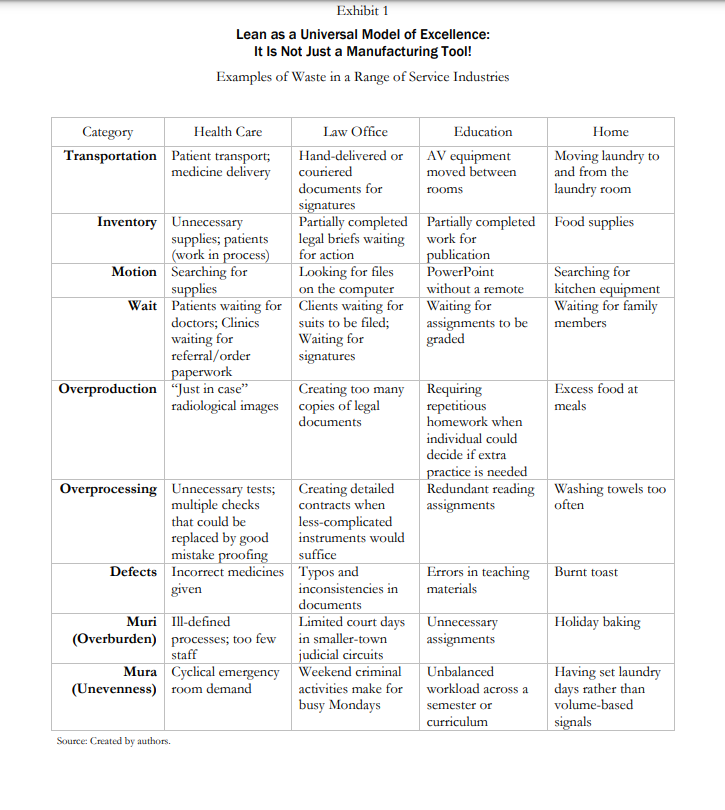

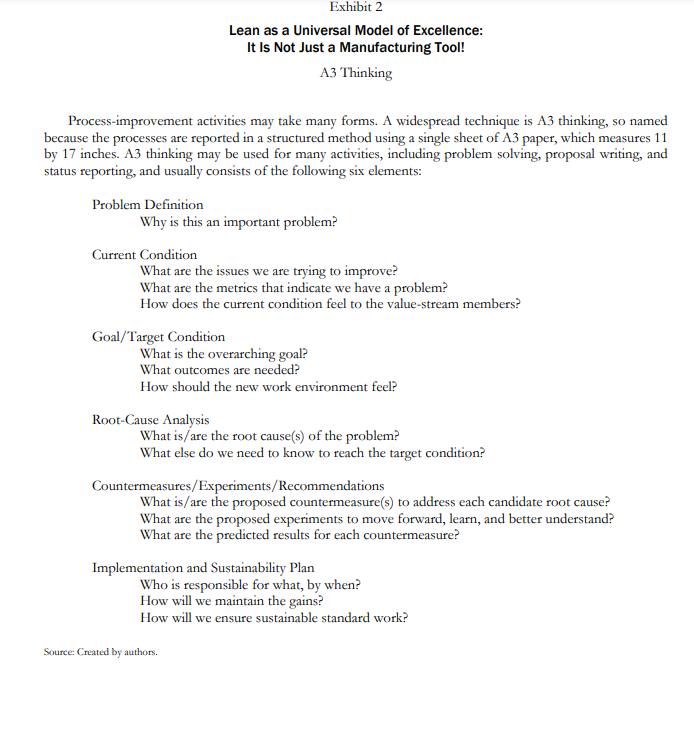

Lean as a Universal Model of Excellence: It Is Not Just a Manufacturing Tool! Lean is a systematic way to enhance value delivery, whatever form that value may take. Lean thinking frames every request for value as an opportunity to improve by teaching participants to notice wasteful action (or inaction), then carefully remove that waste, leaving the value intact. This can be achieved by anyone following three basic premises. First, once you set a standard for any means of value creation, that standard must be protected relentlessly, not as an isolated project but a continuous mission; this involves engaging and empowering everyone in the enterprise. Second, the criteria for improvement and priorities for implementation should pull directly and strategically from the needs of the customer. Third, the best way for value delivery to approach its ideal form is for changes to comprise removing waste wherever found, regardless of scale; what remains will reveal what is essential and invite a new evaluation, in a virtuous cycle of refinement. Lean is not rocket science. We like to define Lean as common sense rigorously and vigorously applied. Many of the solutions and recommendations are elegant in their simplicity. The hard part comes early, when initial implementation likely requires a shift in organizational culture toward heightened collaboration, empowerment, and cross-functional trust. Many firms attempt Lean transformations as a series of transactional improvements, but such attempts inevitably yield superficial and temporary results; for the necessary transformational change to occur, radical reforms are usually required, and some may not like it, at least at first. But once a firm survives that initial period of disruption, the improved conditions, workflow, and productivity tend to speak for themselves. Notice that the word manufacturing has not been used in the above descriptions. The evolution of Lean techniques and vocabularies took place within manufacturing but has never been limited to it. In retrospect, yes, postwar Japanese manufacturing can be seen as uniquely fertile ground for the blossoming of such a system, but with every new application of its lessons, it becomes clear that Lean methods are universal in nature. Lean thrives on waste, and waste is everywhere. Lean's Early Development After the Second World War, Toyota could not possibly have employed the mass-production techniques of Ford and General Motors (GM), even if it had wanted to. Henry Ford's assembly-line model leveraged economies of scale and division of labor at the expense of choice ("any color, so long as it's black"); Alfred Sloan of GM adapted Ford's model to provide a modicum of product variety and customization. Toyota had neither the capital to invest in such scale nor the market presence to justify it. What Toyota did have was Taiichi Ohno, a mechanical engineer who started at the original Toyota, a spinning and weaving company, then transferred to Toyota's automotive division when the former dissolved in 1943. Within a few years following the war, Ohno was managing an engine machine shop. His means of controlling cost was not scale, which was prohibitive, but the elimination of waste, which might be anywhere. For Ohno, the idea of the loom as an autonomous machine maintained by human vigilance persisted as a metaphor in his mind, "a text book in front of my eyes." The notion of maintaining a steady flow of work through constant monitoring and improvement came naturally. Meanwhile, Kiichiro Toyoda, son of the company's founder and initiator of its transition to automobiles, had a vision, also inspired by the automated looms, of what would eventually be known as just-in-time inventory management. With the proceeds from his father's sale of loom patents, Toyoda presciently purchased simple and flexible manufacturing equipment, which allowed Ohno to retool frequently and experiment with small batch sizes of components. In this manner, Toyota (the firm) was able to make a variety of vehicles in relatively low numbers better matched to demand, with higher levels of quality and fewer defects. The process was inherently constructivist-that is, learned by doing-with elements adopted pragmatically from a range of sources, including American and German manufacturing. Most important, factory workers were empowered to innovate and refine as they went. The process was not even documented until 1965, as the company sought to set up a pull system with its suppliers. A mere decade later, in the early-to-mid-1970s, oil prices forced a reevaluation of industry practices in the United States. This, in turn, led to the transfer of the Toyota system to the United States and to the development of a vocabulary of Lean. Ever since, Lean has increasingly been revealed-as its proponents have long understood to be universally applicable to any enterprise in any culture. Origin and Implications of Lean as a Term The term Lean emerged in opposition to existing terms used to characterize manufacturing processes, perhaps most obviously in contrast to the "mass" in mass production. But it also emerged from a benchmarking model used by Haruo Shimada, a visiting professor at MIT during the study of the automotive industry in the 1980s.3 Shimada saw manufacturing on a continuum according to the manner in which it addressed risk. Western firms were deemed more "robust" or "buffered" due to the strategy of storing vast inventories and retaining redundant workforces as hedges, a figurative layer of fat taken on as insulation from any contingency, bringing with it large, unacknowledged, and unnecessary costs. In comparison, Japanese firms, considered by Shimada to be at the other end of the spectrum, were first described as "fragile," perhaps in the sense of vulnerable, then "Lean," to avoid negative connotations. Yet "fragile" bears a clue to another way of thinking about Lean, in terms of attunement, nurturing, or sensitivity: a clear and prompt acknowledgment of any flaw, so that fixing it becomes more imperative. Robust, buffered operations may be insulated from shock, but they may also encourage an indifference to detail, an imprecision born of volume and overreliance on insurance, such as inventory maintained "just in case." To some, the term Lean may suggest austerity. The irony is that a Lean operation is in no way starved-on the contrary, it retains everything it requires and only rejects what cannot nourish it anyway. A better metaphor related to nourishment might be that, as unnecessary additives and contaminants are removed, the nutritional impact of the main ingredients increases. Lean does not "make do." It allows an operation to thrive by removing distractions and returning constantly to what is most important. Ohno's Categories of Waste: TIM WOOD (and U) There are two Japanese terms and phrases associated with the diagnosis of a problem. "Going to the gemba," or factory floor, suggests that no theory or metric will help so much as the detailed concrete information of direct observation, so the "gemba walk," or tour of the production space, is a routine element of Lean management. Kaizen, literally "change for good," can refer globally to continuous improvement efforts, but frequently refers to a specific campaign or heightened investigative exercise in response to a perceived opportunity to improve. Theoretically, such scrutiny should be happening at all times, but the emergence of a defect sometimes presents an opportunity to redouble efforts and leverage momentum. Central to Ohno's approach was the identification of muda, or wasteful activity; mura, unevenness in demand; and muri, unnecessarily difficult or complex activity wherever it was found. Ohno arrived at seven categories of waste, since then often organized in English into the mnemonic TIM WOOD. TIMBOOD Transportation Inventory Motion Waiting Overproduction Overprocessing Defects Transportation Workflow is neither direct nor smooth. Workflow with multiple zigzag movements and multiple material-storage locations creates inefficiencies that result in excess transport. Inventory Inventory in excess of immediate needs. This inventory may occur because of a push system where work is done in order to keep resources busy. In a production environment, inventory may be raw material, work in process, or finished goods Inventory is often undesirable because (a) it includes wasted labor to create it at unnecessary times, (b) is a common cause of much rework since it hides defects, and (c) is an easy indicator of "fat" processes with rampant confusion and excessive lead time. Motion Non-value-adding movement by workers. Widely dispersed material and excessive bending and reaching by the operator are examples of this type of muda. Poor work-center layout and poor storage procedures are causes of unnecessary operator motion. Such motion may be either physical (looking for a hard copy of a file) or virtual (looking for a file on a computer drive). Waiting Inefficient work sequence. Workers and other resources may be waiting for other workers or resources to finish a task, or work itself may be waiting for a worker or resource to become available. Overprocessing Work that adds no value, as defined by the customer, to the product or service. Redundant processes and continuous changes in quality standards are characteristics of processing waste. They are caused by such things as unclear customer standards and poor process design. Overproduction Producing ahead of demand or producing in excess of demand. Overproduction can be recognized by variation in the workflow, excessive finished-goods inventory, and large batch sizes. Overproduction can result from an absence of procedural standards, poor forecasting, and lengthy setup times. Defects Rework, scrap, and returns. Excessive scrap and customer complaints are indicative of defects. Improper material and poor-quality workmanship/design are causes of this type of muda. By their nature, defects tend to be discovered after the fact-and are usually frowned upon rather than celebrated. Defects may be further characterized as "turnbacks" (defects found within the process) or "escapes" (defects found by the customer). In terms of reputation, turnbacks may be celebrated as opportunities for improvement, whereas escapes are to be responded to but loathed. In some cases, the matter is isolated and easily rectified; in others, the matter is systemic and calls for investigation. Untapped creativity Frequently, a final form of waste is included for consideration: untapped creativity, or the squandering of an opportunity to enlist the imagination of those who perform the work in the solving of problems. Workers in a Lean operation are given the latitude to improvise solutions as needs arise, and failing to do so can be considered a form of opportunity cost. In this vein, another of our working definitions of Lean is a continuous attempt to improve safety, quality, flexibility, and productivity by involving all employees in problem solving every day. Lean Considerations in a Service Setting Lean is often about a range of small enhancements that, added up, enhance operations to a surprising extent. Exhibit 1 provides examples of the seven traditional waste categories in a range of service settings. The same categories exist in both manufacturing and service businesses, but they may reveal themselves in different ways. One potential obstacle is that service workers accustomed to focusing on big ideas or responding to client urgency may consider some of these examples too mundane to matter much. What they may not realize is that the tiniest removal of unnecessary activity will tend to make a process substantially more sensible, clearing away unnecessary distractions that otherwise would add up. The benefits may only become obvious after the waste is removed, but to harried workers, the resulting boost in productivity can be like manna from heaven. Transport, inventory, and motion involve the movement through space of objects, their storage, and the worker's physical movements, respectively, so some may assume that spatial considerations are more relevant to manufacturing. But office work frequently benefits from the elimination of transportation needs, albeit on a smaller or even symbolic scale. Attention, like retooling, often requires setup and transition time. As easy as it is to generate electronic files, they require a sequence of actions best reserved for when the files are needed and not before, and their destination should be accessible to any who require them. If documents require printing and distribution, the time and energy required for transport of such things can add up quickly. How colleagues confer can frequently involve time and movement out of proportion to the information sought, so some types of information requests might best be batched and submitted at specified times, whereas time-sensitive information might be sought via instant messaging. Measuring what can be measured Services produce measurable output even when not producing a physical good.4 A mortgage-processing firm "produces" approved mortgages; a hospital "produces" healthy, discharged patients; a publisher "produces" published books. The processes that produce these services may be depicted by value streams that track products or services from receipt of an order to delivery of a final product. The goal of value-stream analysis is to document the existing process and establish the standard form the work is to take. See Exhibit 2 for one common process-improvement framework. Success stories Examples of Lean implementation in service settings are surprisingly rare, maybe because accessible stories about abstract processes are harder to write. Nevertheless, successes are out there.5 Pal's Sudden Service is a fast-food restaurant headquartered in Tennessee that has embraced Lean principles. Through a combination of standard work, product focus, and work simplification, the firm is capable of servicing automobiles through its drive-through lanes at the rate of one every 18 seconds while reducing error rates to an industry low. Below are some health care examples: The emergency room in Lynchburg (Virginia) General Hospital used Lean thinking to help reduce waiting time and the number of patients who "left without being seen." Principles used included setup- time reduction and standard work. Value-stream deployment was applied to the hiring, credentialing, and onboarding process for newly hired medical staff. An improved understanding of the cross-functional, interdepartmental nature of approving new medical staff reduced the new-hire process from an average of three months to an average of three weeks. + Restaurants are usually classified as services but still produce a physical product: meals. The Lean Anthology is a collection of fictionalized applications of Lean tools to both service organizations and everyday life. Service examples include coffee shops and supermarkets. Personal examples include blood-sugar monitoring for diabetes patients, the making of popcorn, household inventory management and general home organization. Rebecca Goldberg and Elliott N. Weiss, The Lean Anthology: A Practical Primer in Continual Improvement (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2015). *In 2001, the firm won the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award from the National Institute of Standards and Technology at the U.S. Department of Commerce. See Rebecca Goldberg and Elliott N. Weiss, "Pal's Sudden Service: The Right Recipe," UVA-OM-1506 (Charlottesville, VA: Darden Business Publishing, 2013); and Rebecca Goldberg and Elliott N. Weiss, "The Secret Sauce in Pal's Sudden Service's Success? Streamlining," Washington Post, November 15, 2014. Rebecca Goldberg, Chris Thomson, and Elliott N. Weiss, "A Pediatric Emergency Room at Lynchburg General Hospital," UVA-OM-1523 (Charlottesville, VA: Darden Business Publishing, 2015); and Rebecca Goldberg, Elliott Weiss, and Chris Thomson, "Innovation Helps Lynchburg General Hospital Serve Emergency Patients Better," Washington Post, September 5, 2014. The radiology department was able to double its monthly volume of medical-imaging procedures while eliminating overtime and increasing employee satisfaction through a series of kaizen activities that emphasized the development of Lean standard operating procedures, flow of patient care, and process ownership. A remote clinic improved its scheduling process and patient-care effectiveness through better attainment of patient medical records, improved patient flow, and the development of a clinic-wide patient-dismissal process using a cross-functional team and A3 process-improvement thinking. A redesigned value stream for the clinical-research-project approval process replaced departmental silos with a cross-functional team, decreasing response times and increasing approval percentages. A kaizen analysis of a surgery clinic uncovered opportunities to improve workflow, ultimately leading to reduced patient wait times and increased patient satisfaction. Commonly observed causes for bottlenecks included multiple simultaneous initial visits, inefficient clinic layout, and inflexibility of staff roles. Using Lean principles, changes were made to improve clinic efficiency, including (1) limiting the number of initial visits during a single time block, (2) taking vitals in patient rooms to allow simultaneous review of patient charts, and (3) cross-training staff to perform multiple roles within the clinic. Summary Although initially developed in a manufacturing setting, Lean principles are applicable in any setting, including a service enterprise. The key is to clearly define the desired outcome, then examine the process by which it is delivered, looking for instances of non-value-adding activities. This is not a job for one person, but for everyone in the firm. As such, Lean requires an environment of collaboration and trust, so that people are not only trained to identify waste, but empowered to remove it. Exhibit 1 Lean as a Universal Model of Excellence: It Is Not Just a Manufacturing Tool! Examples of Waste in a Range of Service Industries Category Health Care Law Office Education Transportation Patient transport; Hand-delivered or AV equipment Home Moving laundry to medicine delivery couriered moved between and from the documents for rooms laundry room Inventory Unnecessary supplies; patients (work in process) Motion Searching for supplies Wait Patients waiting for doctors; Clinics waiting for referral/order paperwork Overproduction "Just in case" radiological images signatures Partially completed legal briefs waiting for action Looking for files on the computer Clients waiting for suits to be filed; work for publication without a remote Waiting for assignments to be Waiting for graded signatures Creating too many Requiring copies of legal repetitious documents Partially completed Food supplies PowerPoint Searching for kitchen equipment Waiting for family members Excess food at meals Overprocessing Unnecessary tests; multiple checks Creating detailed contracts when less-complicated instruments would that could be replaced by good mistake proofing suffice Defects Incorrect medicines Typos and homework when individual could decide if extra practice is needed Redundant reading assignments Washing towels too often given Muri Ill-defined (Overburden) processes; too few staff Mura Cyclical emergency (Unevenness) room demand inconsistencies in documents Limited court days in smaller-town judicial circuits Weekend criminal activities make for busy Mondays Errors in teaching materials Burnt toast Unnecessary Holiday baking assignments Unbalanced workload across a semester or curriculum Having set laundry days rather than volume-based signals Source: Created by authors. Exhibit 2 Lean as a Universal Model of Excellence: It Is Not Just a Manufacturing Tool! A3 Thinking Process-improvement activities may take many forms. A widespread technique is A3 thinking, so named because the processes are reported in a structured method using a single sheet of A3 paper, which measures 11 by 17 inches. A3 thinking may be used for many activities, including problem solving, proposal writing, and status reporting, and usually consists of the following six elements: Problem Definition Why is this an important problem? Current Condition What are the issues we are trying to improve? What are the metrics that indicate we have a problem? How does the current condition feel to the value-stream members? Goal/Target Condition What is the overarching goal? What outcomes are needed? How should the new work environment feel? Root-Cause Analysis What is/are the root cause(s) of the problem? What else do we need to know to reach the target condition? Countermeasures/Experiments/Recommendations What is/are the proposed countermeasure(s) to address each candidate root cause? What are the proposed experiments to move forward, learn, and better understand? What are the predicted results for each countermeasure? Implementation and Sustainability Plan Who is responsible for what, by when? How will we maintain the gains? How will we ensure sustainable standard work? Source: Created by authors.

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started