Question: Management Science Journal - Please read and summarize the attached journal entry. The summary should discuss the main finding(s), the methods used, the implications of

Management Science Journal - Please read and summarize the attached journal entry. The summary should discuss the main finding(s), the methods used, the implications of the work, and, importantly, your own assessment of pros and cons of each article. In the latter part, you need to demonstrate critical thinking.

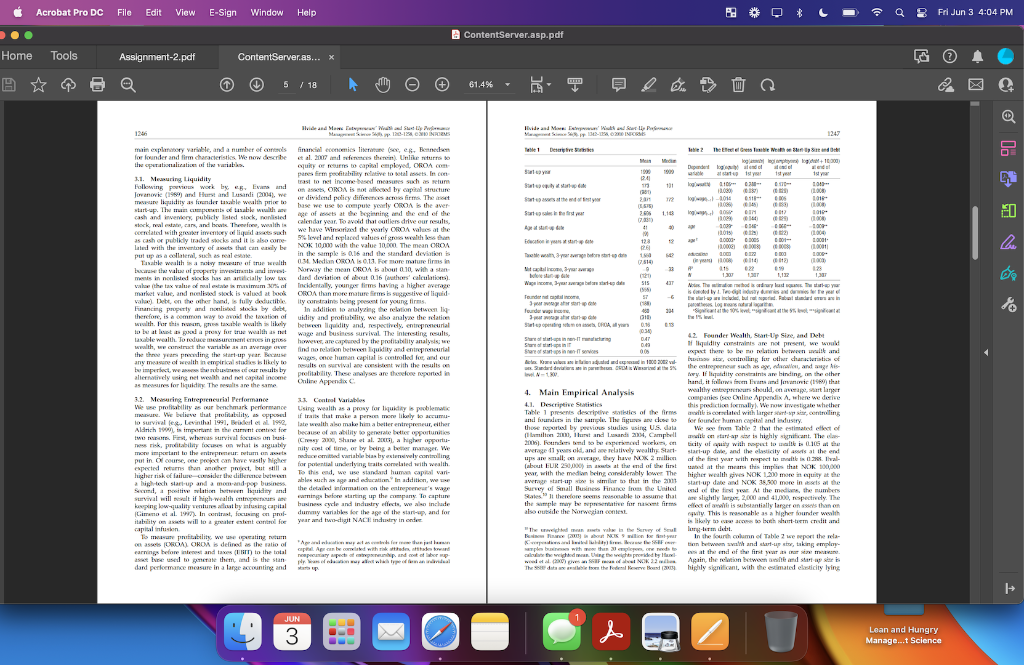

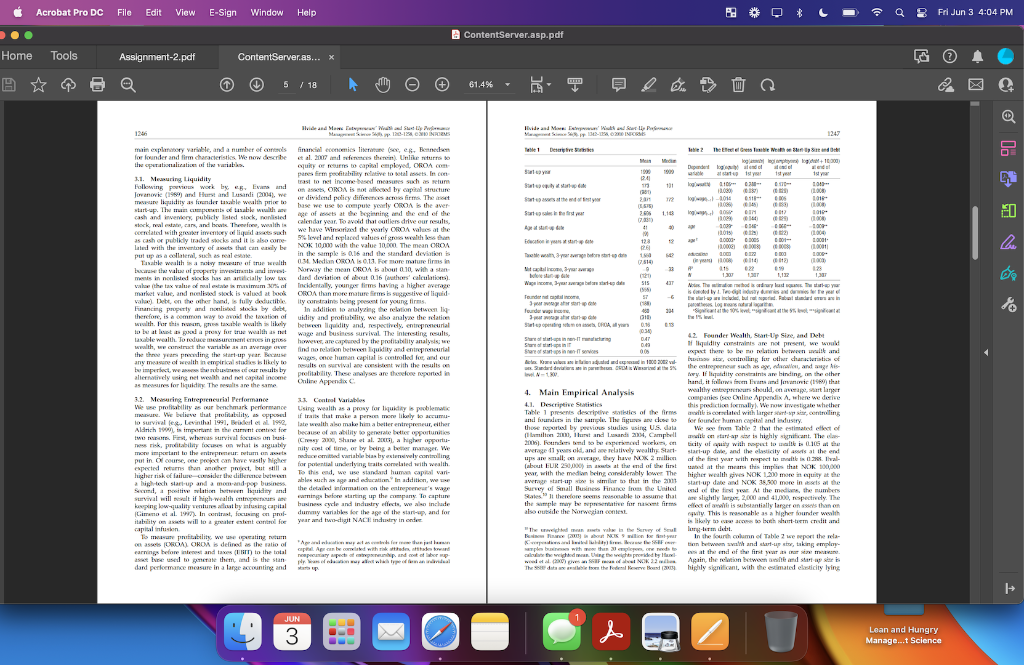

Acrobat Pro DC File Edit View E-Sign Window Help Assignment-2.pdf ContentServer.as... x 1 / 18 MANAGEMENT SCIENCE informs 101297/11177 DINICUM Vel 56, No. 8 Agust 2000, pp. 122-1258 HAND25-19091536590||10|5061282 Lean and Hungry or Fat and Content? Entrepreneurs' Wealth and Start-Up Performance Hans K. Hvide School University of Aberdos, Cd Aberdeen A4 30 Scotland, harbideak Jarle Meen Norwegian School of Economics and Bukos Administration, 5045 Bergen, Norway, jate moichhre entrepreneurs are liquidity constrained and not able to bomow to openite on an efficient scale, economic theory predicts that repeneurs with more personal wealth should do better than those with less wealth We test this hypothesis using a nevet data set covering a large part of start-ups from Norway Corsistent with liquidity contains, we find a positive relation between founder price wealth and start-up size. The relationship between price wealth and start-up performance, as measured by profitability on assets, inces in the first three woulth quarties. In the top wealth quartile, however, protibility drops sharply in weath. Our finding are consistent with a houry good interpretation of empieurship and that higher weil may induce a less alent or less dedicated management. We conclude that an abundance of suces might do more harm than good for start-up Kry: enteral motivation entrepreneurships financial constraints; liquidity; organizational stock: start-ups, survivat, produbility History: Rived December 28, 2009, accepted January 30, 2010, by Scott Share, pean Pied online in Articles in Aalance May 28, 2008. Let me have men about me that are fat, sleek headed men, and such as sleep o'rights. Yend Cassius has a lean and hangry look; He thinks too much such men back to Plate, who in his Reevic wrote that wealth is the panent of luxury and indolence (Plato 2008, p. 377) Who should we place our bets on, Adam William Shakespeare (Caser, Act 1, Scene 2) 1. Introduction One of the oldest ideas in the study of entrepre neurship is that entrepreneurs may be liquidity con strained and therefore unable to establish a venture at the right scale. To illustrate this point, Adam Smith (1869, p. 117) d the example of the owner of a small grocery store, who must Using a newly collected data set from Norway on a large presentative sample of start-ups, our search investigates the effect of liquidity, as measured by mounted's phor wealth, on start-ups and start-up profitability. To avoid capturing effects that go via more wealthy founders being more able, we control for human capital via age, education, and prior wage variables. We also control for business cycle. and industry effects. The strength of the relationship between founder seealth and start-up performance, as measured by profitability on assets, increases over the bottom three quarties of the wealth datribution, and decreases sharply in the upper wealth quartile. These findings suggest that a moderate amount of liquidity may post sinneurial performance, consist with Smith's view, but that an abundance of liquidity may do more harm than good, consistent with Plato's view be able to read, write, and account and must be tolerable judge of, perhaps, fifty or sixty diff sorts of goods, their prions, qualities, and the markets where they are to be had cheapest. He must have all the knowle, in short, that is nosary for a great merchant, which nothing hinders him from being but the want of an h 1860, Book 1, Chip. M Whenas Smith held a favorable view of the effects of more liquidity, business people and venture capitalists caution that excess liquidity can facilitate overinvestment or adversely affect the entrepreneur's motivation and alermess. The idea that more liquidity can have a negative effect on outcomes can be traced and the founder's wealth. An entrepreneur that starts The theory of liquidity constraints of Evans and Jovanovic (1999) provides a useful reference point for the empirical analysis. Evans and Jovanovic (1989) classify entrepreneurs as constrained or unconstrained hased on the relative magnitude of the start-up size 1242 JUN 3 Home Tools H 9 ContentServer.asp.pdf 61.4% 00 Hide and Mon ExpWith and Start Lip Preference 1342-15402 INCOM up a company that is small relative to his wealth is defined as uncenstrained. Evans and Jovanovic (1989) predict a negative relation between wealth and profitability for the constrained entrepreneurs, and az elion between wealth and profitability for the unconstrained entrepreneurs. The first prodiction relles on the Evans and Jovanovic (1999) assumption of returns to scale. The second prediction decreasing is very general and will hold in any theory of liquidity constraints based on profit maximisation. We estimate that profitability on asses incruses by about eight percentage points from the 10th so with perele. This new suggests that liq- uidity constraints could stop entrepreneurs from being able to exploit a "hump" in marginal productivity because of a region of increasing returns to scale. At the top of the wealth distribution, our estimates seg gest that the profitability on avets dys by about 11 1 pentage points from the 75th to the 100th per centile. That profitability decreases for some range of entrepreneurial wealth is what one would expect if marginal profitability decreases as start-ups rach their optimum scale. It is, however, puzzling that prof itability on assets falls sharply in the range of wealth where entrepreneurs are least likely to be liquidity constrained One explanation for why the relation between liquidity and profitability is negative in the upper wealth quartile could be that liquidity constraints bind for some of these founders, and that such con straints combined with suitable assumptions about the returns to scale inside the firm-are sufficiently strong to create a downward slope in profitability Although we do not observe the scale returns of indi vidual start-ups, we do observe start-up size. Based on the methodology of Evans and Jovanovic (1985), we find that the drop in profitability in the upper wealth quartile is driven by entrepreneurs that are unconstrained. Thus, quite strikingly, the drop in profitability in the upper wealth quartile is due to the lack rather than the presence of liquidity constraints This finding stands in contrast to theories of liquid- ity constraints based on profit maximization, where there should be a zero relation between liquidity and profitability for unconstrained entrepreneurs Data limitations make us unable to pin down exactly which mechanism drives the puzzling inverse U-shaped relation between founder wealth and start up performance. Two types of mechanisms, not mutue ally exclusive, sem useful for understanding the finding organizational slack and private benefits. and () is not the only comic od that predicts a negative and cone nation between liquidity and wh For example, Berband (0) and de Mesa (0) tical frames that can be produce fee prodicom Q 1243 Although there is no universally accepted defini tion of organizational stack, financial freedom is one important aspect (Bourgos 1981, Tan and Pong 2003). Because the financial situation of the founder and of the firm are tightly related for start-ups (eg, Aldrich 1999), the financial freedom of the founder and of the firm are likely to be closely correlated. Management theorists generally tend to argue that slack is beneficial through creating a buller from environmental shocks (Cyrt and March 1963, Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) or allowing for experimentation (Thompson 1967), and thus enhances performance. Cyert and March (1963, induce a 16, caution that slack might ind mering the t lowering of the threshold of acceptable outcomes in the search the search for alternative actions. This argument su gests a curvilinear relation between slack and perfor mance, where there is an optimal level of slack for any given firm. If the firm exceeds that keed, perfor mance will go down" (Sharfman et al. 1988, p. 603). Our findings are consistent with the idea that some slack boots start-up performance, but that an ahun dance of slack is harmful We believe that the negative effects of slack can be understood by considering entrepreneurial moti vation, in particular the notion that entrepreneur no ship is a luxury good (Hamilton 2000, Moskowitz and Vissing Jongen 2002, Harst and Lusandi 2005). If f entrepreneurship is a houry good, wealthy indi viduals are willing to forgo income to enjoy it private benefits. Several nenpecuniary motivations for entrepreneurship have been analyzed by the entrepreneurship literature, typically by comparing answers to survey questions for entrepreneurs and mempromur Asingh we have to direct way mentrepreneurs of finding out which nonpecuniary motivations are more important in our sample, our results are consis tent with the notion that entrepreneurship gives social esteem or Independence (Hiszich 1985, Homaday and Aboud 1973, Aldridge 1997), and that more wealthy individuals have a greater demand for this. Our find ings this complement the existing entrepreneurship literature by suggesting that nonpecuniary motiva tions can have a large quantitative impact on start-ups and by pointing out which types of entrepreneurs are most likely to act upon normonetary motivations. "Is the cont of muhase, the empiricall on the wip between slack and performance has been conce and Pring 28, Table 1 an S to find evidee of a curve on (eg. Besky 1991. Mil and in 195) Nohris and Glauseination as a dependent variable, and devia slide slack and inovation, whes Tan and Peng (2008) find a v to be sack and profitability of Ch med pris Se et al (200) provide an excent review of the leade QFri Jun 3 4:04 PM o Lean and Hungry Manage...t Science you yo Acrobat Pro DC File Edit View E-Sign Window Help Assignment-2.pdf ContentServer.as... x 3 / 18 1244 Most earlier studies on entrepreneurial performance have had limited access to sociodemographic infe- mation about the founders, and have analyzed the relation between start-up performance and variables such as firm size (eg. Beidel et al. 1992, Audretsch and Mahmood 1995) rather than the relation between start-up performance and founder variables. The pre- vious research with access to entrepreneurial wealth measures has analyzed the relation between liquid- ity and entrepreneurial wages (Evans and Jovanovic 189) and the relation between liquidity and start- up survival (Holtz-Fakin et al. Hop Evans and 1994) Jovanovic (1989, Table 3, p. 82) find that a dou- bing of founder wealth is associated with a 14% increase in self-employed earnings. This result is hand to interpret, however, because the authors are unable to control for the possibility that investment levels (and hence earnings) tend to increase with founder wealth. Noe do Evans and Jovanovic (1999) control for wealthier founders having higher effective human capital. In contrast, our detailed data allow us to con trol both for investment levels and for human founder capital. Holtz-Eakin et. al. (1994) use data on the taxes of a site of received inheritances from large estates, and find that a $150,000 inheritance increases the survival proba bility by 13 percentage points (p. 5). Because this sample of entrepreneurs tend to have very high prein- heritance incomes, the authors cannot conclude that liquidity enhances the survival of the typical new venture. In contrast to Holte-Eakin et al. (1995), the date set we use covers a representative sample of start-ups. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the data Section 3 discuss our empirical strategy Section 4 contains the emple ical analysis, 55 provales further analysis and dis cusses limitations, and 6 concludes and discusses research implications. Three appendices are avail able in the e-companion. In Online Appendix A we derive formally the hypotheses from the Evans and Jovanovic (199) model. Online Appendix B contains some additional discussion on the empirical relation ship between wealth and start-up sise. In Online Appendix C we analyze the relations between liquid- ity and, respectively, entrepreneurial wage and busi ness survival. Online Appendix C contains Tables 5-7. 2. Data The data come from Norway and consist of a random. sample of limited liability firms that were incorpo rated between 1994 and 2002. The data are organized *Se K and Nanda (2018) for at and entwiew of An election companion to this paper is axalable as part of the on ne veien that can be found at http://mancijournalist Home Tools H 9 Hide and Most Wand St Map 120-1258, e30 INFORM as a yearly panel ranging from 1992 to 2006, and con tain incorporation and accounting information on the start-up in addition to detailed sociodemographic information about all founders with at least 10% own- enship shame. Because the data are novel, we start out with a brief description of the Norwegian economy and of the data collection. Norway is an industrialized nation with a popula tion of about 4.5 million. The gross domestic product - per capita in 2002 was about $40,000 when cur cies are converted at purchasing power parity; this is higher than the European Union average of $6,00 Norway is characterized by a large middle class and than a lower inequality in disposable income than most other industrialized nations. Norwegian houshakle are subject to both a capital income tax and a wealth tax every year throughout their lives (in contrast, the US tax system requires wealth reporting only in connection with estate tax, which is imposed only on the very rich at the time of death, as described in Campbell 2006). Because of the existence of the wealth tax, the government's statistical agency, Stat tics Norway (abo known by its Norway SSB) collects yearly data on wealth and income at the individual level from a variety of sources, including the Norwegian Tax Agency, welfare agencies, and the private sector. Financial institutions supply informa tion to the tax agency on their customers' deposits, interest paid or received, security investments, and dividends. Employers similarly supply statements of wages paid to their employees. The data set is compiled from three different Sources: 1. Yearly accounting information from Dus & Bad streets (D) database of accounting figures based on These data include variables such as sales, assets, the annual financial statements reported by the comp nies. profits, and five-digit industry code for the years 1994-2005. It is important to note that the D&B data contain all Norwegian incorporated companies, not a sample as in the US. equivalent. 2. Yearly data on indishads from 1986 32 - paral by Statistics Nerany. These reconds include the anonymized personal identification number and yearly sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, education, wealth, interest payments, and cam ings split into labor income and capital income. Eam- ings and wealth figures are public information in Nor way. This transparency is generally believed to make tax evasion more dficult and, hence, our data more reliable. We use these data to construct measures of founder background and founder wage income after "The description of the Norwegian economy is based on the 2002 and 2000 editions of the Statistical Yearbook of Norway The year books available at http://www.be/english/book/ JUN 3 ContentServer.asp.pdf 0 61.4% Q Hvide and More With and Safe 1342-12502 INCOM 1245 and NOK 100,000 thereafter NOK 50,000 is equiva lent to about EUR 6,300. Incorporated companies are required to have an external auditor certifying the accanting statements in the annual reports starting up a venture. The Statistics Norway data con tain all Norwegian Individuals, not a sample as in, eg, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics of the Sur vey of Consumer Finance 3. Fanding den bitted by we firme t the gay nyugint. These data include the personal identification number of the founders, total capitalization of the company, and each founder's respective ownership share. Using the founding documents we deline an entrepreneur as a male with more than 50% of the total shares in a newly established incorporated com pany (the average menership share is 8). Restrict ing the sample to majority owners makes us avond the problem of defining liquidity when dealing with multiple founders with different levels of wealth Other advantages include avoiding the problem of An adverse consequence of the low barriers to start- ing up an incorporated company and its favorable tax treatment is that many start-ups, particularly within real estate, are tax shaders, or have minimal activ ity. This problem was dealt with in two ways first, by oversampling manufacturing and information och by nology (IT) because tax shelters are less likely to occur in these industries. We selected all start-ups within the high-tech actors NACE 23-35 and 72 from 1994 to 1998, and all start-ups within manufacturing and IT NACE 15-37 and 72 from 1999 to 2002 We added a random 27% sample of other noefinancial private sec bor start-ups from 1999 to 2002. We expanded the sam pleafter 1996 because the cost of collecting data for the more recent period is lower. Secund, to further reduce the shape of empty shells," firms are included only if they have at least NOK 500,000 (about EUR 63,000) in sales and at least two pessons employed during one For each start-up selected in Dun & Bradstreet's of the first two years of operation. Avoiding sampling database, we compile a list of founders based empty companies is important because the incorpora had on the founding documents Next, we machines to be hand collected by ch located in the founders associated sociodemographic informa- tion from the public registers supplied by Statis tics Norway, Because of alterations in the reporting requirement in 1998, and the transition from paper based to digitally based archiving, we were able to match around 80% of the founders in companies how to deal with nominal founders such as "sleeping spouse Restricting attention to makes avoids mea surement problems with female labor market partici pation. Seven percent of the founders are females and are excluded founded after 1998 and around 20% before. Based on communication with Bronneysund, we have no rea son to believe that the low frequency in which we are able to match for companies started before c ates a base 1998 e ates a bias in any particular direction. This impression is confirmed by comparison of, eg, the size distribu tion of the companies founded before and after 1998 Altogether, we have a sample of about 1,500 unique founders and 10,300 found your observations. In the analysis we lose about 200 founders because of miss ing variable The current data set has several important advan tages compared to earlier data sets used in the study of entrepreneurship. First, a large literature within the entrepeneurship domain has limited generaliability because it is based on the self-employed or nonrep Desentative samples (Delmar and Shane 2006). In com trast, our sample is representative of the population of newly founded incorporations in Norway. Second, relative to other representative data on entrepreneurs such as the Panel Stady of Income Dynamics, the Survey of Consumer Finance, and the Surveys of Small Business Finances (SSB), our data have sev cal strengths. Hecarase our data are collected from government archives, we do not suffer from survey design biases due to noneesponse or imperfect neca of subjects. Also, our data have access to a l long panel with yearly and multiple measures of entrepreneurial pericemance. This enables us to perform a time-series analysis and a variety of robustness tests. Finally, we have detailed data on the wealth and wage history of Like in other industrialized countries, setting up an incorporated company in Norway carries tax benets relative to being self-employed (eg, more beneficial was formed in mobil write-offs for expenses such as home office, company car, and computer equipment), and incorporation sta tus will therefore be more tax officient than self- employed status except for the smallest projects. The formal capital requirement for registering an incorpo rated company was NOK 50,000 in equity until 1998 the founders. This enables us to control for founder human capital and liquidity much more comprehen sively than in previous studies. 3. Empirical Strategy Our regression models have start-up performance as the dependent variable, liquidity of the founder as the "Even if the names of the founden in some might be dis sed, obtaining and using data based on maining or lees week be a lack of the condity age mont with Static Norway and would violate Norwegian low NACE sefers to the Norwegian Standard Industrial Clawitication of 2000 2000) et les on the Tempen Union Standard NACE Revision 1. See Si Nowy Q8 Fri Jun 3 4:04 PM o Lean and Hungry Manage...t Science. ya yo Cu Acrobat Pro DC File Edit View E-Sign Window Help Assignment-2.pdf ContentServer.as... x 5 / 18 Hide and Moments Weath and S Masappoikien M120-12583 INFORM www main explanatory variable, and a number of controls for founder and firm characteristics. We now describe the operationalization of the variables. 3.1. Measuring Liquidity Following previous work by eg. Evans and Jovanovic (1989) and Hurst and Lusandi (2004), we mesure liquidity as founder taxable wealth price to start-up. The main components of taxable with an cash and inventory, publicly listed stock, nonlisted stock, real estate, cars, and howts Therefore, wealth is stock, real estate, cars, and how h correlated with greater inventory of liquid assets such as cash or publkly traded stocks and it is also come lated with the inventory of assets that can easily be put up as a collateral, such as real estate. financial economics literature (see, eg. Bennedsen et al. 2007 and references therein). Unlike returns to equity or returns to capital employed, OROA com pares firm profitability relative to sotal assets. In con trast to net income-based measures such as return Pap on assets, not by capital structure ucture or dividend across firms. The asset is base we base we use to compuse yourly CROA is the aver age of assets at the beginning and the end of the calendar year. To avoid that outliers drive our results, we have Winsorized the yearly OROA values at the 9% level and replaced values of gross wealth less than NOK 10,000 with the value 10,000. The mean CROA in the sample is 016 and the standard deviation is dev sals and the stan 0.34 Median OROA is 0.13. For more mature firms in Norway the mean OROA is about 0.10, with dard deviation calculations). Incidentally, younger firms having a higher averago OROA than more mature firms is suggestive of liquid Can think ity constraints being present for young firms. The e 0.16 (stan In addition to analyzing the relation between liq Taxable wealth is a noby measure of true wealth because the value of property investments and invest ments in nonlisted stocks has an artlicially low tax value (the tax value of mal estate is maximum 30% of market value, and noelisted stock is valued at book value) Debt, on the other hand, is fully deductible Financing property and nonlisted stocks by debe therefore, is a common way to avoid the tation of uidity and profitability, we also analyze the relation we also wealth. For this reason, gross taxable wealth is likely liquidity and, respectively, entrepreneurial to be at least as good a proxy for true wealth as net wage and business survival. taxable wealth. To reduce measurement erroes in gross however, are captured by the profitability analysis, we wealth, we construct the variable as an average over find no relation between liquidity and entrepreneurial the three years preceding the start-up year. Because wages, once human capital is controlled for, and our any measure of wealth in empirical studies is lik is likely to results on survival are consistent with the results on be imperfect, we assess the robustes of our results by alternatively using net wealth and net capital income profitability. These analyses are therefore reported in Online Appendix C as measures for liquidity. The results are the same between the interesting results, 33. Control Variables 3.2. Measuring Entrepreneurial Performance We use profitability as our benchmark performance mure. We believe that profitability, as opposed to survival (eg, Levinthal 1991, Brder et al. 1992, Aldrich 1999), is important in the current context for two reasons. First, whereas survival focuses on busi- ness risk, profitability focuses on what is arguably the more important to the entrepreneur return on assets Using wealth as a proxy for liquidity is problematic if traits that make a person more likely to accumu late wealth also make him a better entrepreneur, either because of an ability to generate better oportunities (Cressy 2000, Shane et al. 2000), a higher opportu- nity cost of time, or by being a better manager. We reduce omitted variable bas by extensively controlling for potential underlying traits correlated with wealth. To this end, we use standard human capital vari- as ables such an age and education. In addition, we se information on the entrepreneur's wage earnings before starting up the company. To capture put in Of course, one project can have vastly higher expected returns than another project, but still a higher risk of failure consider the difference between a bigh-tech start-up and a mom-and-pop business Second, a positive relation between liquidity and survival will seelt if high-wealth entropeeneurs are keeping low quality ventures afloat by infusing capital (Gimeno et al. 1997). In contrast, focusing on prof itability on assets will to a greater extent control for the detailed and t business cycle and industry effects, we also include dummy variables for the age of the start-up, and for year and two-digit NACE industry in ceder To measure profitability, we use operating noturn on assels (OROA) OROA is defined as the ratio of earnings before interest and taxes (ET) to the total asset base used to generate them, and is the stan dand performance measure in a large accounting and "Agen wat ass for expital Age can be comiated with risk attades nepairy pech entrepreneurship, and ply as of eation may at which type of p de of her of labor p an individual JUN 3 Home Tools H 9 licy diced ContentServer.asp.pdf 0 61.4% Q Hvide and More Deep With and Start Lip Permane MS 341342-1250200 INFORM 1247 Destive S 2 The Weath sent and De Dependent logpyne g+10000) and of at end of atend Endel 1st year 1st your Stay 12.41 17 at startup 1st year 0.30- - 4105 100800 AND (157) 011- (2008) 1016 100 san 006 State and of your Stat -40 HOM ARD 1812 146) DIM 11029 Ing 1918 00000 (7) A 41 apr DE -4009 -6346 (2015) 1900 www 10000 w Education sta age (2004) 10001 darati 128 0.0005 0001- 124 se (2000) (261 (0001) 100+ 1960 1.000 003 Tw3yr average before start-up d No3-yuraverage 07.410 1008) (14) (100) @ 6.19 9 AP N 415 1,307 Wag inom 3-average before start-up da Tudom 515 (956) 57 1,307 1,307 Not Thethod is ordinary last squares. The start-up your nation bad isted by Teodyt industry unies and driester the year of sant ed, but at Fastandard as an in personal Sigit at the 10% leveligt at the vict x 15 3-year gear stude founder, GID 3 nap de Sapopeting Ar 0.16 (0.34) Share on nen-Tacturing Share of Share of startups innen Te 0.47 0.49 values and inflation adjusted and Standard deviations are in partem level N-1,800 in 1000 2002- W% 42. Founder Wealth, Start-Up Size, and Debt If liquidity constraints are not present, we would expect there to be no relation between wealth and insia, controlling for other characteristics of the entrepreneur such as age, education, and ange Ais tory. If Iquidity constraints are binding on the other hand, it follows from Evans and Jovanovic (1969) that wealthy entrepreneurs should, on averago, start langer companies (see Online Appendix A, where we derive this prediction formally). We now investigate whether meat is correlated with larger start-up size, controlling for founder human capital and industry. 4. Main Empirical Analysis 43. Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the firms and founders in the sample. The figures are close to those reported by previous studies using US data (Hamilton 2003), Thirst and Lusands 2004, Campbell 2006). Founders tend to be experienced workers, on average 11 years old, and are relatively wealthy Start- ups are small; on average, they have NOK 2 million (about EUR 250,000) in axts at the end of the first year, with the median being considerably lower The average start-up sine is similar to that in the 2013 Survey of Small Business Finance from the United States. I therefore seems reasonable to assume that the sample may be representative for nascent firms also outside the Norwegian contest We see from Table 2 that the estimated effect of on start-up size is highly significant. The clas ticity of quity with nopect to alte is 0.105 at the start-up date, and the elasticity of assets at the end of the first year with respect to mealth is 0.288. Ival and at the means this implies that NOK 100,000 higher wealth gives NOK 1,200 more in equity at the start-up date and NOK 38,300 more in assets at the end of the first year At the medians, the numbers are slightly larger, 2,000 and 41,000, respectively. The effect of all is substantially larger on asses than on equity. This is reasonable as a higher founder wealth is likely to ease access to both short-term credit and "The weighted matsvile in the Servey of Seat long-term debt. your Best Finance (2003) in about NCIK 9 million for In the fourth column of Table 2 we report the rela Kpdated day) se hetin between swalth and start-up sine, taking employ samples with more than 30 empleen, one needs at the end of the first year as our sine m cathewigheden. Ung the weights preded by Hand wood et al. (2000) gives an man of het NOK 22 The data are able from the Federal Reserve Bound (200 Again, the relation between with and start-ups highly significant, with the estimated elasticity lying 101 1.148 40 12 437 -6 204 Q8 Fri Jun 3 4:04 PM o Lean and Hungry Manage...t Science. Acrobat Pro DC File Edit View E-Sign Window Help Assignment-2.pdf ContentServer.as... x (@ 13/18 1254 Hide and Ms Extern Wealth and Start L Map 120-128, 03 NORM more wealthy). This mechanism makes it important. to emphasize that our estimates are only valid for the vult of individuals that start-up a busins at this current wealth level, but our estimates are mute on the effect of increased wealth on the entry and per formance of nonentrants A related selection problem is that because wealth affects business survival, our estimates of the effect of wealth on performance will capture the effect on the firms that survive, but will not capture the effect of providing more liquidity to those that do not wor vive but might have done so with more liquidity. This mechanism is to have an effect for low-and we do not have direct measures of the quality of management, an entrepreneur dedicated to profitabl ity of the new venture ses more likely to spend time inside the venture. We analyzed the probabil ity that the entrepreneur has the start-up as his main employer (e, the job with most hours put in per wwwk) When 85% of the entrepreneurs in the bot tom 95% of the wealth distribution have the start-up as their main employer at the end of the second year of operations, the corresponding figure for entrepreneurs in the top 5% of the wealth distribution is 66%. The au in passat is at the 1% is tent with more wealth implying less dedication or medium-wealth entrepreneurs in that these require a higher level of profitability to continue operations of business (levinhal 1991, Gimena et al. 1997), but is unlikely to have a large effect on the wealthy entrepreneurs. Thus, this mechanism does not seem very important for our main realt Initiatives that increase entrepreneurial liquidity such as government subsidies, will allect the compo sition of entrants and the composition of businesses that survive. It is theriore of interest to evaluate the That wealthy entrepreneurs spend less time with their start-ups could be because they have many busi- ness engagements or that they enjoy a relaxed style. Although we do not observe the number of bus- ness engagements of the entrepreneurs in our sam ple, we are able to construct proces for their total work loads. We have analyzed () the number of hours per week that the entrepreneurs work with their main employer, (i) the number of employment relation- ships outside the main employer, and (ii) whether or not entrepreneurs that are not employed in their start- up are employed full time elsewhere. These exercises do not suggest that wealthy entrepreneurs withdraw from the labor market to enjoy a relaxed fentyl direction of the bias introduced by the attrition effects that we are not able to estimate. A prior it is more likely that both selection effects, enery, and survival, are likely to affect low-wealth individuals more than high-wealth individuals, because the former are mo likely to be liquidity constrained. If the nomentrants and nonsurvivors are marginal in terms of profitabil l ity, then an estimate of the relation between w and profitability that includes selection effects is likely to have a stronger upward slope than the estimates we obtain The differences in the propensity to be involved was the firm arms the wealth dire chees a concem: are we just observing different subsan ples? For example, do those who are more wealthy ruma portfolio of companies, one as a tax shelter and the other as a real business? Or are these just "angel investors" who are investing in pet projects, financing friends' projects, etc., and not really running their own business De our meals continue to hold 6. Wealth, Underperformance, and Nonpecuniary Benefits if we include cely those who continue to work in their businesses until they exit? With respect to angel investors, we should recall that we focus on major ity owners. It seems very unlikely that a person who is merly being out friends or family would hold Our findings provide vidence that a higher founder wealth can hurt the performance of start-ups. This result holds for start-ups whose entrepreneurs are in the upper quarale of the wealth distribution In this section, we analyze the underlying mech anisms for this relationship. One possible explana- tion is that higher wealth induces the entrepeenr to become less alert or less dedicated to the man agement of the company. This would be consistent with the notion of entrepreneurship being a luxury good, giving such benefits as social estom or inde pendence (Hamilton 2000, Moskowitz and Vissing Jorgensen 2002, Hurst and Lundi 2004). Although a majority share. To elaborate on the role of founder presence, we nun a regression where we only include years where the founder is employed by the company. The results are tabulated in Table 3, column (7). The estimated coefficients are not statistically significantly w The standard approach to solving those selection problems ist Heckman (1979) two-step procedex. This method is one the ability of variables that are likely to be colated with ndry (but not with predibility. It is very hard to ble with the properties that can act an instruments Weakly slightly fears that less wealty inters, but this toip is for from significant Wedno lationship at all between wealth and the member of ployment relationshipside the prog that are not employed in their start-up of the with below modkan wealth as employed feller. For kworks with wealth in the 50-25 percentile and 75-100 percent 50% employed there JUN __ 3 Home Tools H 9 ContentServer.asp.pdf 61.4% Q MS 1342-15402 INCOME 1255 deters high-wealth, low human capital, individual from starting up a company. Because it is hard to think of variables that are correlated with entry but not with performance, we have not been able to make progress on this question using Heckman (1979) type techniques. We have, however, investigated whether the relationship between wealth and entry is simi lar to that in Hurst and Lusandi (2004). Our analysis of this question suggests that the relation between log(lt) and the propensity to start-up a business is at up to the 50th wealth quantile, and then increases monotonically throughout the upper wealth quantile This result seems equally consistent any son with liquidity constraints and with the luxury good interpretation of entrepreneurship. different from zere, but the estimated relationship between wealth and profitability is curvilinear and very similar to the relationship estimated in column (3) Thus, our results do continue to hold if we include only entrepreneur-yers where the entrepreneur has the start-up as his main employer. We nest expand the regressions in Table 3 with a dummy variable that equals one if the owner is employed in the start- up. We find a strong, positive, and significant effect of this dummy, and the estimated negative wealth- performance relationship among the most wealthy les become. However, a clear, negative effect steep. of It is possible that wealthy entrepreneurs view entrepreneurial activity as some form of charity. One indication of such preferences would be that wealthy entrepreneurs pay their workers higher wages than entrepreneurs motivated by profits. To investigate this possibility, we identified all workers employed by the new ventures in our sample and ran a standard Mincer wage regression. We added controls for the wealth of the entrepreneur prior to starting the new venture, controls for the profitabday of the new venture, and interactions between these variables. On a sample of 26,850 observations of 9,960 individual workers, we tried, altogether, 14 different specifications including both polynomials and dummy variable approaches We found no evidence suggesting that there is an inter action effect between COA and wealth of the kind that one would expect to find if the underperformance of wealthy entrepreneurs was driven by their firms paying whip is a luxury good, richer individ high wais uals are more likely to start up companies, and these In addition to excess entry, richer entrepreneurs could be more prone to keep failing companies afloat. If that were true, we would expect the negative cross- sectional relation between profitability and wealth to become stronger the older the population of firms. To investigate this hypothesis, we added an interac tion term between firm age and founder wealth in the egins in Table 3. Although the estimated coff cients were negative, they were close to zero and far from being statistically significant. Thus, this does not seem to be a major mechanism behind our findings 7. Concluding Remarks 7.1. Discussion companies will (at least at the margin) be of poor quality because their primary purpose is to satisfy the entrepreneur's nerpecuniary needs. This mech anism would be consistent with Hurst and Lusandi (2004), who, using US. dana on the self-employed, found that the relation between wealth and entry is flat for the main bulk of the wealth distribution, and sharply increasing at the top. It would also be con sistent with Nanda (2006), who structurally estimated the Evans and Jovanovic (1989) model using a tax reform in Denmark and found that less liquidity We have analyzed the relation between liquidity, as measured by founder wealth, and performance, as measured profitability, by pretty using data for a large and representative panel of start-ups in Norway. We find a positive relation between founder wealth and prof itability in the lower 75% of the entrepreneurial wealth distribution, and a strong negative relation between founder wealth and profitability in the upper 25% of the wealth distribution. That start-up profitability decreas in wealth on some interval of the would distribution is what one would expect if marginal profitability decreases as start-ups reach their eff cient scale. It is, however, quite striking that the profitability drops sharply in the high-wealth region, where entrepreneurs are least likely to be liquid- ity constrained. This finding stands in contrast to economic theories of liquidity constraints based on profit maximization, which peedict a zero relation between liquidity and profitability for unconstrained Note futes of this to should be ked with a in base to work the sat up or not in an enge schoon Hvide (2008) ses frunder death as a qui experiment But gende variation in owner pence. His findings at pacedoes not have a large impact on t up performance prepared for each by Stats Norway entrepreneurs gemand wee Dola limitations make us unable to pin down exactly which mechanism drives the puzzling inverse U-shaped relation between founder wealth and start up performance. Two types of mechanisms, not matu sale However is in 52 does not get ally exclusive, seem useful to understand the finding organizational slack and private benefits. It would also be that richer entre start up companies at an P Q8 Fri Jun 3 4:04 PM o Lean and Hungry Manage...t Science. ya yo