Question

M-L Fasteners, GmbH case set in West Germany in 1986 in the apparel fasteners industry. The issue is cost analysis for a bundled business. My

M-L Fasteners, GmbH case set in West Germany in 1986 in the apparel fasteners industry. The issue is cost analysis for a "bundled" business.

My biggest concern is keeping prices up in the face of Japanese competition. We do not want to lose market share to them, but their prices are so much lower than ours that matching them would be too expensive. They do not present an immediate threat because our quality is so much higher. However, even though our customers who carefully analyze the situation decide to stay with us, they are left wondering if they might be better off buying japanese.

The worst scenario i think of is the Japaneseimporting thousands of their attaching machines and pricing their fasteners below cost in an attempt to dominate the European market. If they did that, Europe would become battlefield. Sales Manager Mr. Brune, European

THE BUSINESS

Snap fasteners are a substitute for buttons in the garment industry. ML produced 700 differend fasteners in four major product lines: "SS," "RINGS," "PRONGS," AND "TACKS." In 1985, ML introduced a new fashion line of prong and tack fasteners they were manufactured from a wider range of materials in a broader variety of shapes and finishes. Mr. Esslinger, the companys market manager, wanted to convince the market that snap fasteners could be a fashionable replacement for conventionial buttons in a wide array of clothing. Fasteners were customized by color or finish or by embossing the customer's logo on the cap.

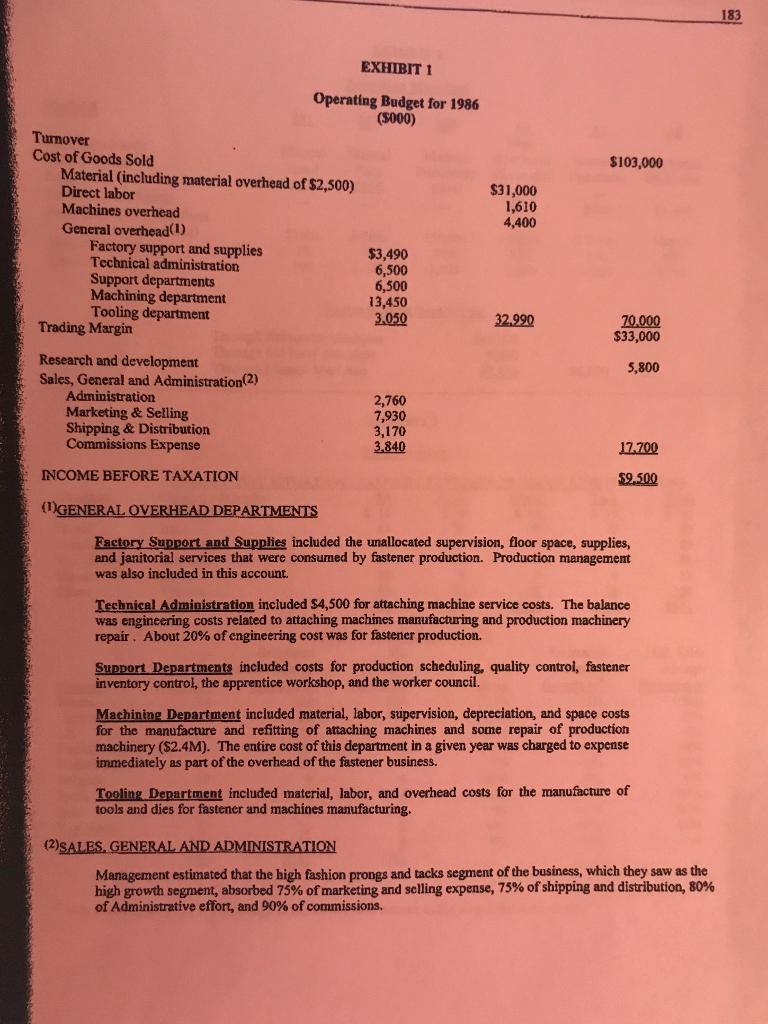

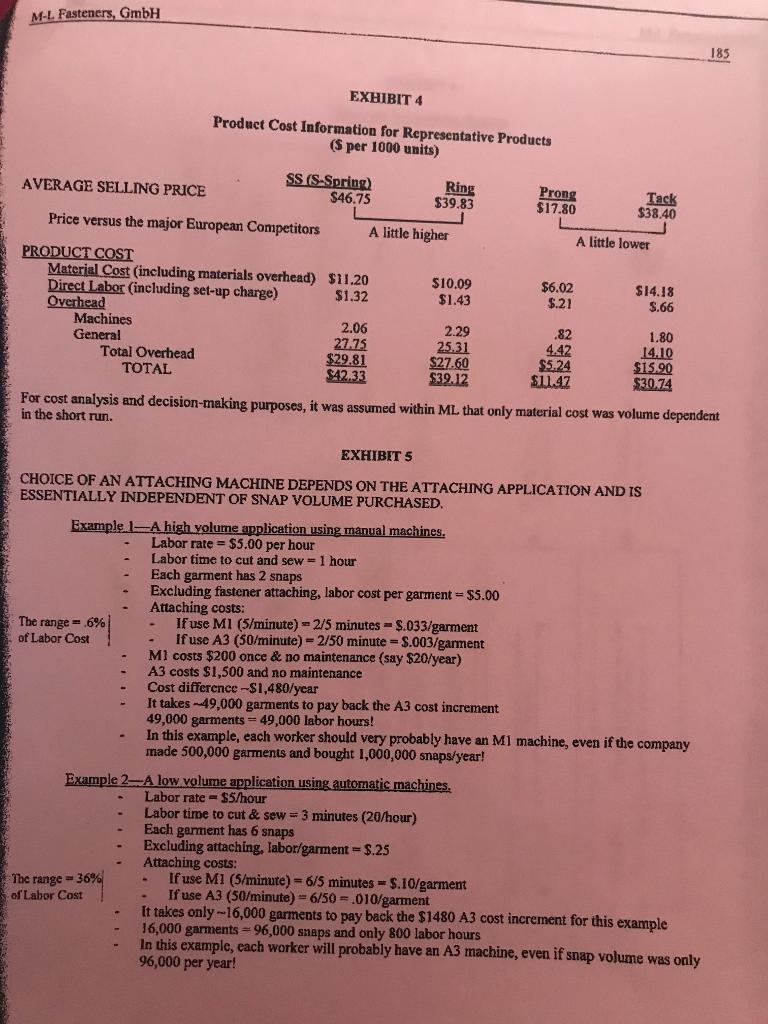

As part of their strategy to expand the market for high-end snap fasteners, ML also manufactured the machines that attach fasteners to the fabric. in 1986 ML manufactured 6 different attaching machines, three manual and three automatic (exhibit 2). Each of the machines could be modified to attach any of the company's fasteners. An operator using a manual machine placed the two parts of the fastener into the machine by hand, positioned the material, and activated the machine. In an automatic machine, one or more parts were automatically positioned, but the operator still had to position the material manually. The type of garment application determined whether a customer would pay the extra cost for an automatic machine.

Over the years, the firm had developed a policy of selling manual machines and leasing automatic ones. manual mahines, unlike automatic machines, were inexpensive to produce, did not require service, and were easily and inexpensively modifIed to attach different fasteners, Automatic machines were rented on an annual basis, though ML was willing to take them back at any time. on average, 10% of the 7,000 rented machines were returned each year. The company inventoried these machines until new machines arived. They then modifed the old machines to attach a different fastener. modifation was expensive, as it required replacing all components specific to the fastener. The company estimated that an average modification cost $2,000.

It was industry practie to provide preventive maintenance and emergency service at no charge. even though most large customers had downtime insurance, ML veiwed reliability and fast service response as important sales tools. it was not unusual for service personnel to fly to a customer within hours of an emergency call. In 1986, service was expected to cost $4.5 million. To partially make up for this cost, ML required that only ML fasteners be used on the machine. The average rented machine attached about $7,000 of fasteners per year.

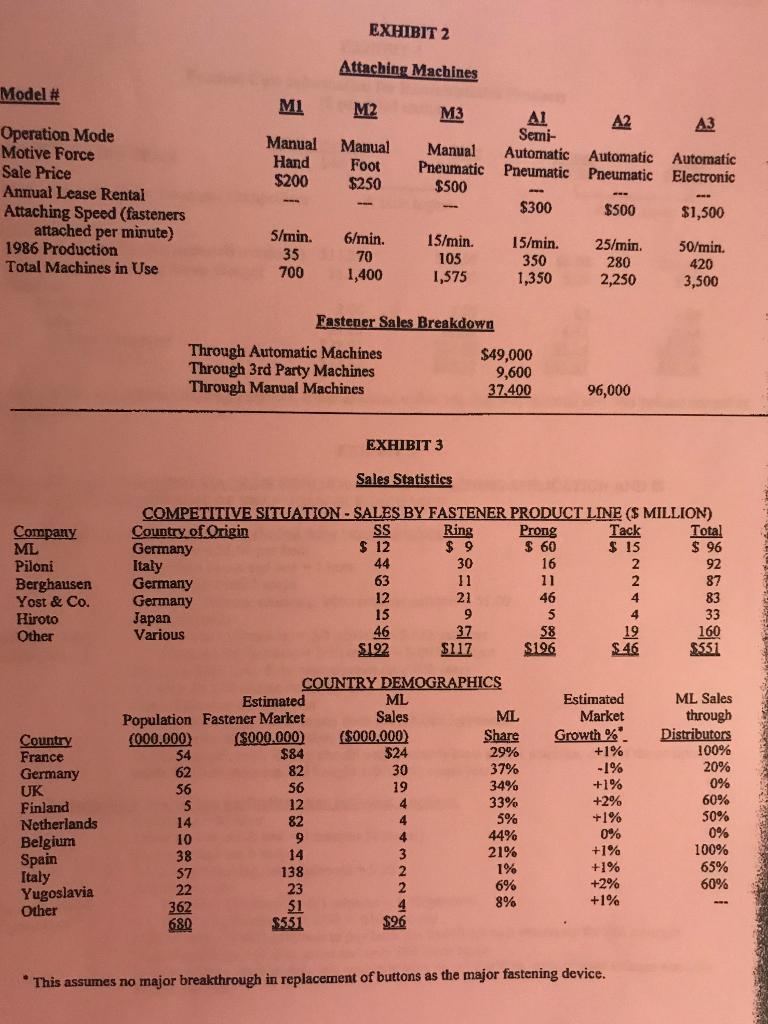

The European market was mature (1% growth) and could be charachterized as a "stable oligopoly" in which four firms together accounted for 65% of sales (exhibit 3). An additional 13 firms (including the japanese) accounted for the remaining sales. Most firms sold fasteners and attaching machines, but there were several companies who only produced attaching machines, but there were several companies who only produced attaching machines. Their machines were usually cheaper and of inferior quality to ML's. About 10% of ML's fastener sales were to customers using third-party machines. The exact percentage was unknown because ML could not be certain on which machines their fasteners were actually used.

The four major players all provided comparable services, never initiated price wars, and rarely tried to steal each other's customers. Customers sourced from multiple suppliers, but the companies developed long standing personal relationships with their customers. Also, the policy of renting machines and of designing fasteners that could only be used in the supplier's machines made switching an expensive undertaking. In addition, there were virtually no standard prices, with each customer paying whatever could be negotiated. This made it difficult to compete on price. The firms competed primarily on three dimensions:

1. The quality of the fasteners and, in particular, the tolerance to which they were manufactured. The higher the quality, the less likely fasteners were to cause machine downtime and the longer their life expectancy once fastened.

2. The performance of the attaching machine; in particular speed, reliability, safety, noise level, and ability to attach fasteners without scratcing the surfaces.

3. The quality of service provided.

ML sold fasteners through agents in some countries, distributors in others, and regional sales offices in yet others. Attaching machines were always purchased or rented directly. In countries where ML maintained a regional sales office, large customers could purchase directly from the firm at reduced prices.

The production process

ML's production facility was a four story building located next to the head office in Duesseldorf. The top floor fo the building contained the machining and tooling departments and was primairily dedicated to the production of attaching machines.

Machining. The machining department labor force produced new attaching machines, refitted returned attaching machines and repiared machinery for fastener production. Except for refitting costs, 80% of the work was on attaching machines.

Tooling. The tooling department designed, manufactured, and repaired all thetooling that was used in the production of both fasteners and machines. Tools used in the production of fasteners were very costly and were frequently reworked. Tools used in the production of attaching machiens were relatively inexpensive and were usually replaced when they showed signs of wear. Perhaps 20% of the cost of this department related to attaching machines production.

The other three floors of the factory were each dedicated to one of the three major steps in fastener production: stamping, assembly, and finishing.

Stamping. In stamping, the material components were stamped out of large coils of various metals. If teh fastener was being produced in very large quantities, automated machines were used that coudl producte up to 12 components with a single stamp. At low production volumes, less sophisticated machines were used. The stamping department contained 47 different types of machinesm and it was not unusaly for a single operator to run several machines simultaneously.

Assembly. In assembly, the stamped components were combined by machine to make the top piece and bottom piece of a fastener. The type of machine used to assemble the components again depended on the production volume, There were 112 different types of machines in assembly. Once assembled, the parts were chemically washed and, if required, heat treated before being sent to finishing.

Finishing. Several different processes were used to produce different surface treatments, including plating, painting, or enameling, tumbling, and polishing. There were 15 different types of machine sin the finishing department.

General. Only minimum work in process and finished good inventories were maintains, because most fasteners were produced to order. While fasteners appeared to be simple products, in fact, they had to be machined to within a hundredth of a milimeter. This required precision stamping and high quality control.

Similarly, the attaching machiens were on the forefront of automated material handlign technology. To maintain their technological superiority, ML maintained a stron research and development department. The recent introduction fo the fashion line required signification R&D resources. Management estimated that about 75% of current R&D projects were related to the new high fashion prong and tack fasteners.

The cost accounting system

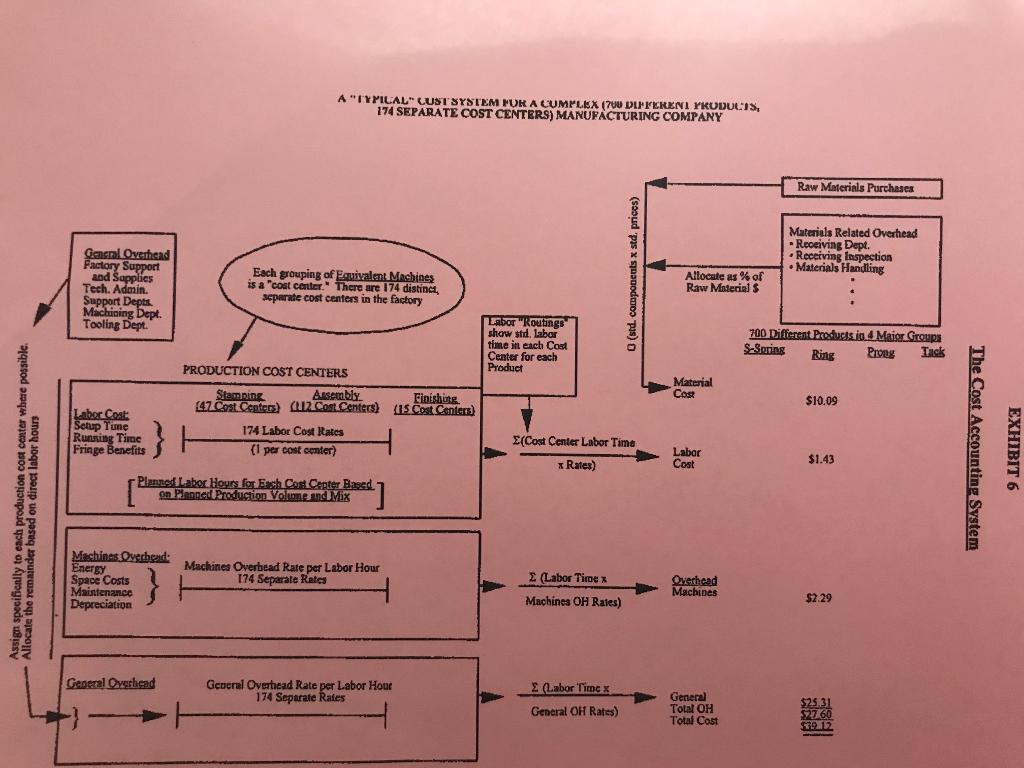

The cost accounting system for ML had recently been overhauled with the help of a leading consulting firm because the old system, which consisted of about 70 cost centers, failed to differentiate appropriately between automatic and manually oeprated machines. The new system contained 174 separate cost centers: one per machine group.

Materials cost. Material, after adjustment for normal scrap, was charged directly to the product. The new cost system also identified a material overhead charge, which included the costs associated with purchasing, material handling, and inventory storage. Products were allocated material overhead on the basis of the material dollars they consumed.

Labor cost. Labor cost, after dividing by the number of machines the operator was running, were charged directly to each product. Setup labor costs, after dividing by the lot size to yield a per part setup charge, were also charged directly.

Overhead was divided into two sections: machines overhead and general overhead. Each product was charged machine overhead and general overhead based on the labor hours it spent in eahc machine group cost center.

Machines overhead. Machine costs were those costs that could meangingfully be assigned directly to the machine, such as floor space, energy, maintenance, or depreciation. The total costs of these items for each machine group was divided by the projected direct labor hours (inclduing setup hours) expected to be worked in that cost center for the coming year to yield a machine overhead rate per labor hour. Thus, there 174 separate machines overhead rates, one for each cost center.

General overhead. General overhead, where possible, were traced directly to the fastener production departments; otherwise it was allocated to departments on the basis of direct labor hours (including setup hours). The general overhead pool for each fastener production department was then divided by projected direct labor hours, yielding a general overhead rate per labor hour. There were alos 174 different general overhead rates, one for each cost center.

Total production cost was the sum of material, labor, machines overhead and general overhead. A schematic of the cost system is shown in exhibit 6. While the different products looked similiar to the inexperienced eye, they could actually have significantly different cost structures. Exhibit 4 shows cost structures for representative products from the four major categories.

The Japanese Competition

Hiroto Industries (HI), the major Japanese competitor in Europe, was a trading company that sold a broad range of fashion accessory products to the shoe, leather goods, and garment industries. Typical products included belts, bcukles, and zippers. HI was about ten times as big as ML, but the two firms competed at only 20% of HI's markets. Unlike ML, HI purchased approximately 85% of the products it sold. The 15% it produced were all high volume, low complexity product lines.

Japan, with 120 million people, and Germany, with 60 million, were not large enough to support multiple domestic producers without significnat export sales. The larger Japanese market with its tradition of high tariff barriers and strong cultural aversion to imported products provided Japanese producers with a significant economic advantage. The high price that Japanese garment manufacturers paid for their fasteners (120% of German prices) reflected the isolation of the Japanese market.

When HI entered the European market in 1973, the substantial entry barriers it faces included the long standing relationships of European companies with customers, HI's lack of high quality attaching machines, and the absence of a network of distributors and service personnel. To help mitigate these barriers, HI focused on high volume niches, such as workwear and babywear, where the market consisted of a few customers ordering in very large volumes. HI identified distributors who were willing to purchase attaching machines elsewhere and then rent them to their customers. HI then supplied these dealers with fasteners at about a 20% discount from current European prices. This strategy had several advantages for HI. Not ownign the machine smeant it did not have to provide service and could keep invested capital to a minimum. The dealers benefited because they could now compete against companies like ML by using their significant price advantage to solicity these customers who were not contractually obligated to use a specific firm's fasteners.

While most fasteners were customized, some of the really high volume fasteners, such as "SS" fasteners, were sufficiently standarized to run on anyone's equipment. Certain ML customers, even though contractually obligated to ML, were known to experiment with the Japanese product. Ml had threatened to cancel the equipment leases if they caught any firm violating the contract. Recently, one firm had been caught, but immediately agreed to stop "experimenting" with Japanese fasteners.

In its 13 years in Europe (1873 to 1986) HI had achieved only about a 6% overall market penetration (exhibit 3). Ml did not consider HI to be a major threat, but they were a constant factor in the market for new customers and high volume users.

Questions:

1. Break the 1986 profit of $9.5 Million down between fasteners and attaching machines (rough approximation to the nearest million is sufficient). What inferences do you draw about the relative profitability of these two segments of the business.

2. One can view the production and leasing of an (automatic) attaching machine as a multi-period "annuity." Money is spent in year zero in order to generate a stream of cash flows (positive net cash flows, hopefully) over an average of ten years. After ten years, a machine is renovated and then generates pisitive cash flows again for another ten years, on average. Try to structure teh time-phased cash flows for this annuity for an "average" automatic attaching machine using 1986 costs and prices. Estimate the interal rate of return. (economic rate of return) for the annuity. How does this calculation change your thinking, if at all, about the profitability of the attaching machines segment of the business.

3. How would you characterize ML's busienss strategy in 1986? Is it reasonable?

4. A. Calculate profitability for the four products in exhibit 4 excluding the impact of attaching machines cost which is part of general manufacturing overhead. The calculation here requires more thinking than crunching.

B. Following on from 4-a what is your assessment of the overall relative profitability of the four product categories.

5. What is the annual ttaching capacity for all the ML machines in the field? Compare this to ML's unit sales volume for all four categories together. What inferences do you draw?

6. Consider the pricing issues and product line issues for fasteners and machines by focusing on exhibit 5 and question 5.

7. What specific recommendations do you have for management regarding "bundling" pricing for fasteners and pricing for attaching machines.

Turnover Cost of Goods Sold Material (including material overhead of $2,500) Direct labor Machines overhead General overhead (1) Factory support and supplies Technical administration Support departments Machining department Tooling department Trading Margin Research and development Sales, General and Administration (2) Administration EXHIBIT I Operating Budget for 1986 (5000) Marketing & Selling Shipping & Distribution Commissions Expense $3,490 6,500 6,500 13,450 3.050 2,760 7,930 3,170 3,840 $31,000 1,610 4,400 32.990 $103,000 70,000 $33,000 5,800 17.700 $9.500 INCOME BEFORE TAXATION (1)GENERAL OVERHEAD DEPARTMENTS Factory Support and Supplies included the unallocated supervision, floor space, supplies, and janitorial services that were consumed by fastener production. Production management was also included this account. Technical Administration included $4,500 for attaching machine service costs. The balance was engineering costs related to attaching machines manufacturing and production machinery repair. About 20% of engineering cost was for fastener production. Support Departments included costs for production scheduling, quality control, fastener inventory control, the apprentice workshop, and the worker council. Machining Department included material, labor, supervision, depreciation, and space costs for the manufacture and refitting of attaching machines and some repair of production machinery ($2.4M). The entire cost of this department in a given year was charged to expense immediately as part of the overhead of the fastener business. Tooling Department included material, labor, and overhead costs for the manufacture of tools and dies for fastener and machines manufacturing. (2)SALES. GENERAL AND ADMINISTRATION Management estimated that the high fashion prongs and tacks segment of the business, which they saw as the high growth segment, absorbed 75% of marketing and selling expense, 75% of shipping and distribution, 80% of Administrative effort, and 90% of commissions. 183

Step by Step Solution

3.45 Rating (155 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

1 Answer SNo Details Overall Fasteners Machines A Turnover 103000 96000 7000 B Cost of Goods Sold 70000 52240 17760 Material including material overhead of 2500 31000 31000 Direct labour 1610 1610 Mac...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started