Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Please answer questions 1-6! GREEN CAST, INC. Green Cast, Inc. produces and sells a line of ovemware (Oven-Sate Classic) that goos from oven (conventional or

Please answer questions 1-6!

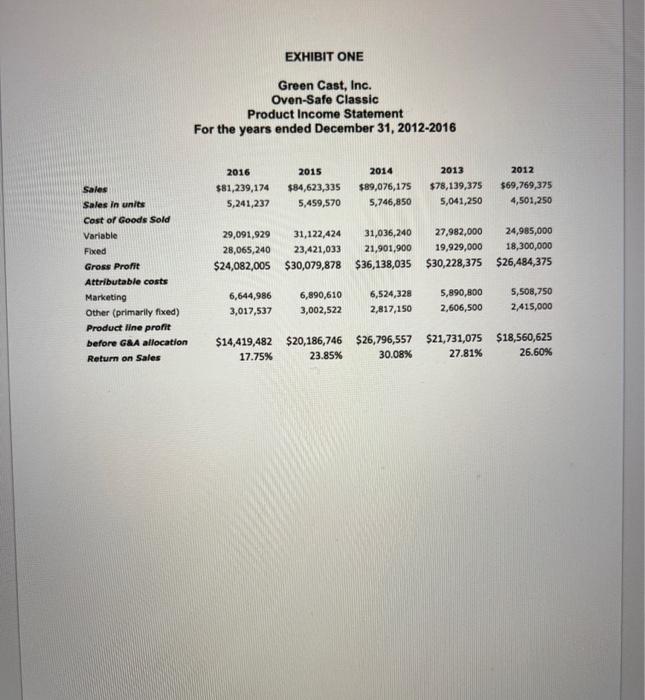

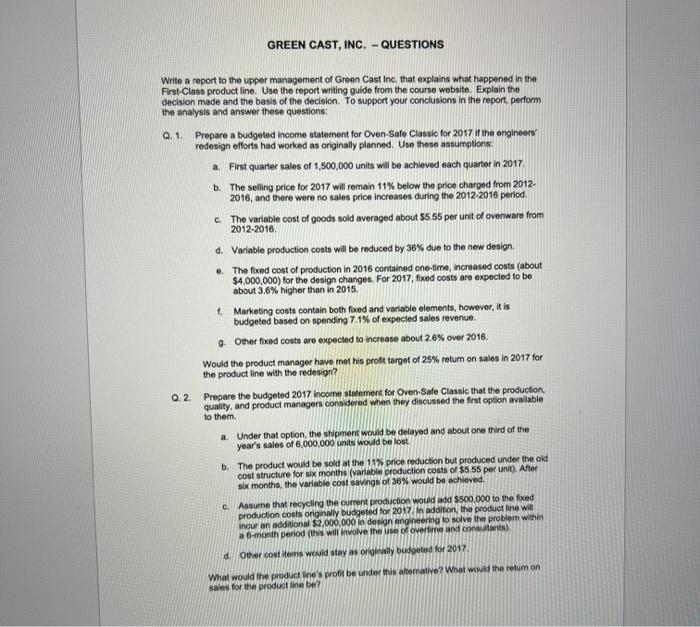

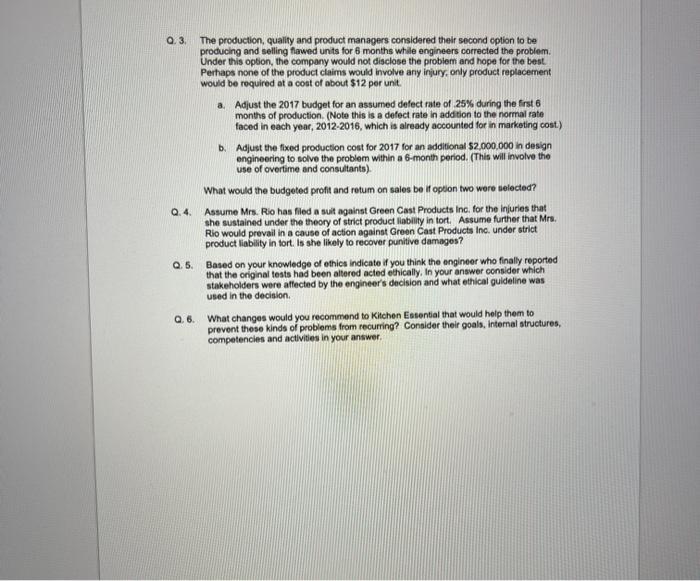

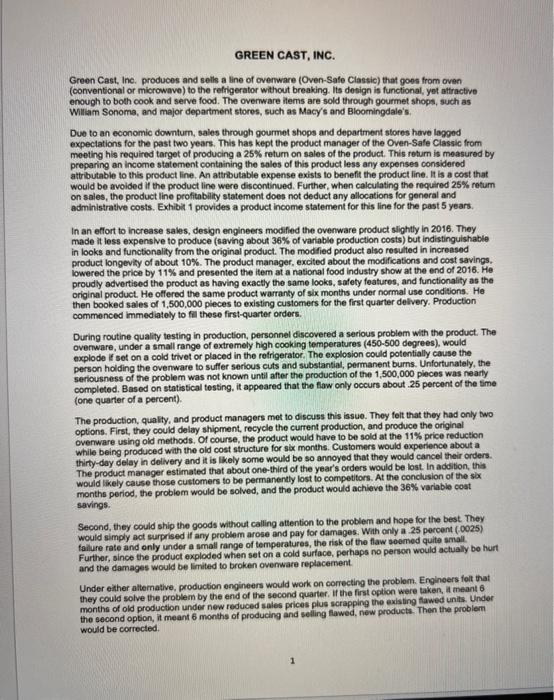

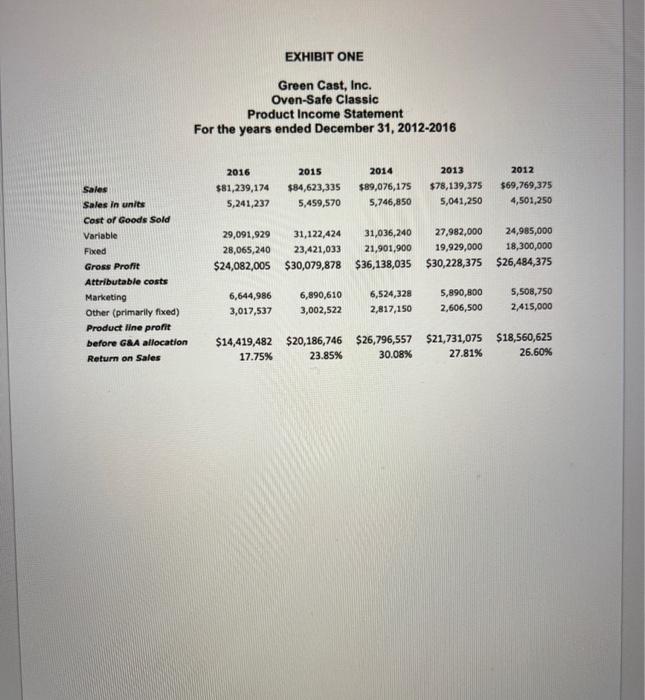

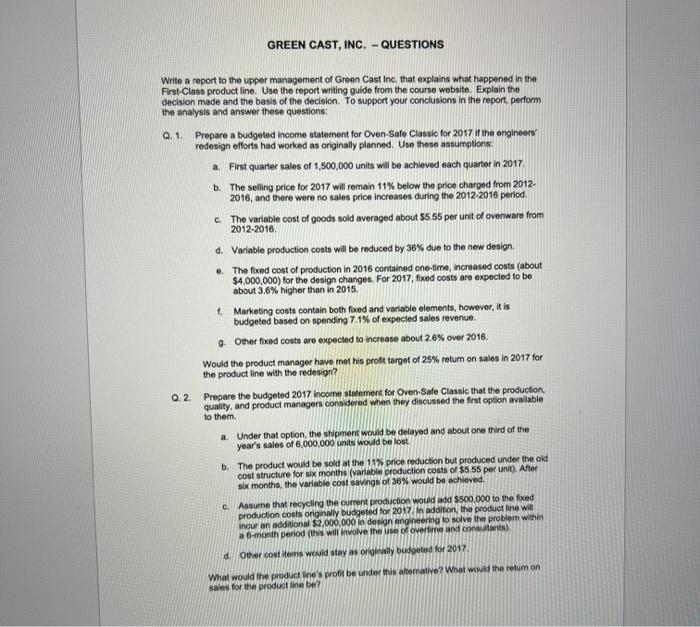

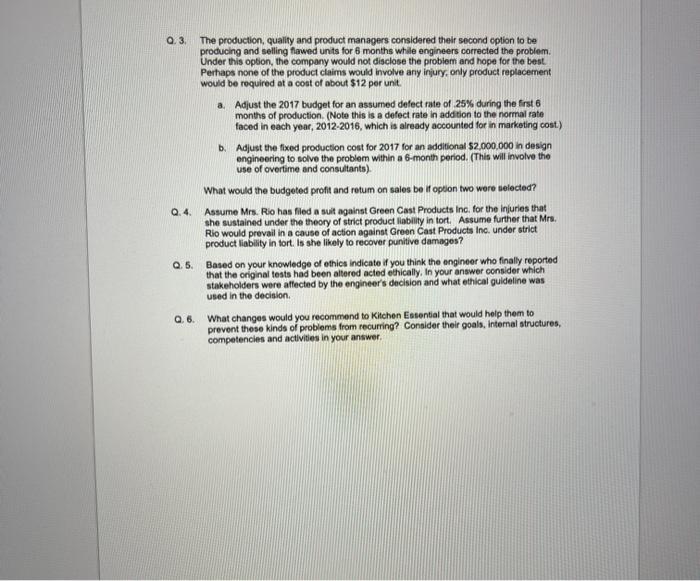

GREEN CAST, INC. Green Cast, Inc. produces and sells a line of ovemware (Oven-Sate Classic) that goos from oven (conventional or microwave) to the refigerator without breaking. Its design is functional, yet attractive enough to both cook and serve food. The overware liems are sold through gourmet shops, such as William Sonoma, and major department stores, such as Macy's and Bloomingdale's, Due to an economic downturn, sales through gourmet shops and department stores heve lapged expectations for the past two years. This has kept the product manager of the Oven-5afe Classic from moeting his required target of producing a 2.5% retum on sales of the product. This return is measured by preparing an income statement containing the sales of this product less any expenses considered attibutable to this product line. An attrbutable expense exists to benefit the product line. It is a cost that would be avoided if the product line were discontinued. Further, when calculating the required 25% return on sales, the product line profitability statement does not deduct any allocations for general and administrative costs. Exhibit 1 provides a product income statement for this line for the past 5 years. In an eflort to increase sales, design engineers modified the ovenware product slightly in 2016 . They made it less expensive to produce (saving about 36% of variable production costs) but indistinguishable in looks and functionality from the original product. The modfied product also resulted in increased product longevity of about 10%. The product manager, excited about the modifications and cost savings, lowered the price by 11% and presented the item at a national food industry show at the end of 2016 . He proudly advertieed the product as having exactly the same looks, safety features, and functionality as the original product. He offered the same product warranty of six months under normal use conditions. He then booked sales of 1,500,000 pleces to existing customers for the first quarter detvery. Production commenced immediately to fin these first-quarter orders. During routine quality testing in production, personnel discovered a serious problem with the product. The overware, under a small range of extremely high cooking temperatures ( 450500 degrees), would explode if set on a cold trivet or placed in the reirigerator. The explosion could potentially cause the person holding the ovenware to suffer serious cuts and substantial, permanent burns. Unfortunately, the seriousness of the problem was not known until after the production of the 1,500,000 pieces was nearty completed. Basod on statistical testing. it appeared that the flaw only occurs about .25 percent of the time (one quarter of a percent). The production, quality, and product managers met to discuss this issue. They felt that they had only two options. First, they could delay shipment, recycle the current production, and produce the original overware using old methods. Of course, the product would have to be sold at the 11% price reduction while being produced with the old cost structure for sbx months. Customers would experience about a thirty-day delay in delivery and it is lkely some would be so annoyed that they would cancel their orders. The product manager estimated that about one-third of the year's orders would be lost. In addibon, this would likely cause those customers to be permanently lost to competitors. At the conciusion of the six months period, the problem would be solved, and the product would achiave the 36% variable cost savings. Second, they could ship the goods without calling attention to the problem and hope for the best. They would simply act surprised if any problem arose and pay for damages. With only a 25 percent (.0025) fallure rate and only under a small range of temperatures, the risk of the flaw soemed quite small. Furthor, since the product exploded when set on a cold surface, perhaps no person would actually be hurt and the damages would be limited to broken ovemware replacement. Under exther altemative, production engineers would work on correcting the problem. Engineers folt that they could solve the problem by the end of the second quarter. If the first option were taken, 1 meant 6. monthe of old production under new reduced sales prices plus scrapping the existing flawed units. Under the second option, it meant 6 months of producing and selling flawed. new products. Then the problem would be corrected. The managers decided that the risk of option two was worth taking and shipped the flawed products (without disclosing the potential hazards). They toned down the quality testing report results such that it appeared that the product might only crack (not explode). Within two months of shipment, things went well. Only 1,575 product claims were made, and none involved personal injury. Replacement items were provided and customers remained satisfied. In the third month, a disaster occurred. Mrs. Rio organized a goodbye party for her son before he went away to college. She prepared her son's favorite chicken and rice dish and cooked it in her oven using the new Oven-Safe Classic that she bought from her local department store. She cooked it at 475 degrees for about two hours and when it was ready, she then placed it in the refrigerator. As the ovenware was placed in the refrigerator, it exploded, spraying glass and hot contents on Mrs. Rio. A glass fragment struck her in the eye. Mrs. Rio also suffered second and third-degree burns on her face, neck, and arms. The accident was reported in newspapers while the department store began investigating its cause. Managers at Green Cast, Inc. acted surprised when contacted by the department store's manager. The product manager of Oven-Safe Classic answered questions regarding the product. He provided the altered quality report to the department store's manager and continued to sell the product while the engineers worked on a solution to the problem. Meanwhile, several other serious explosions occurred, and other people were seriously hurt. Finally, a quality engineer from Green Cast hired an attomey, met with a newspaper reporter, and disclosed that the original test results had been altered. The company was forced to recall all products and halt production. Required Write a report to the upper management of Green Cast, Inc. that explains what happened in the OvenSafe Classic line. Use the report writing guide from the course website. Explain the decision made and the basis of the decision. To prepare for this case, you may want to review managerial accounting LDC concepts 2, 5 and 8; financial accounting concept 9 ; and business law concepts 2 and 9 . EXHIBIT ONE Green Cast, Inc. Oven-Safe Classic Product Income Statement For the years ended December 31, 2012-2016 GREEN CAST, INC. LIBRARY DIRECT SOURCE INTERNATIONAL, INC Appellant v. RHONDA RENA ROBINS, INDNDUALLY AND AS NEXT FRIEND OF JACKE WAYNE ROBINS, JR., A MINOR, AND JACKIE WAYNE ROBINS, SR. Appellees NO. 01-96-01185-CV COURT OF APPEALS OF GREEN, FIRST DISTRICT, HOUSTON July 30, 1998, Date of Opinion July 30, 1998, Opinion lssued PRIOR HISTORY: [** 1] COUNSEL: Stephen F. Malout, Dallas, FOR APPEUANT. Charles W. Seymore, Sugariand, Craig Muessig, Baytown, Evelyn T. Alts, Houston, FOR APPELLEES. JUDGES: Davie L. Wilson, Justice. Panel consists of Chief Justice Schneider and Justices Wison and Nuchia. OPINION BY: Davie L. Wiison OPINION: Appellant, Direct Source Intemational, Inc. ("DSI"), appeals a judgment rendered in favor of appellees, Rhonda Rene Robins, individually and as next friend of Jackie Wayne Robins, Jr., a minor, and Jackie Wayne Robins, Sr. (sometimes collectively relerred to as the "Robins"). Factual and Procedural Background On August 11, 1989, Jackie Wayne Robins, Jr., then three years old, set fre to a plle of clothes with a disposable cigaretle lighter allegedly placed in the stream of commerce by DSi, the manufacturer. The clothes and the lighter were in a van outside his parent's home. As a result of the fire, Jackie Jr. sulfered severe and lasting injuries. Among others, Robins sued DSi for strict product leability in tort aleging defects in the manufacturing. markesing. and design of the Sighter. The primary basis for the Robins' claims was that the lighter did not include a child-proofing or child-resistant design or mechanism to eliminate or reduce the risk that a child such as Jackie Jr. could ignite the lighter. DSI argued at trial that in 1989 there was no duty on the manutacturer to make lighters child-resistant because they were in a certain class of products intended for adult use and not otherwise detective. The Robins argued Green law holds a manufacturer legally responsible for marketing a product not reasonably safe for the products intended use and foreseeable misuse as designed. The judge entered a judgment in tavor of Robins and DSI now appeals. DSi argues a judgment was improperly granted against it because DSi has not produced a defective product. Discussion 4 In Green, a plaintirt injured by an allegedly defective product may seek recovery against the manufacturer on the basis of any one or more of four theories of liability. Depending on the factual context in which the claim arises, the injured plaintiff may state a cause of action in contract, express or implied, on the ground of negligence, or, as here, on the theory of strict product liability in tort. Green courts have adopted the theory of strict products liability expressed in section 402A of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. See American Tobacco Co. V. Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d 420,426 (Green. 1997): Caterpillar, Inc. V. Shears, 911 S.W.2d 379, 381 (Green. 1995). Section 402A provides that any person engaged in the business of sciling products for use or consumption, may be held strictly liable for injuries to the user or consumer of such product, as long as: A. Product was defective: Liability is imposed for products sold "in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer. A product may be unreasonably dangerous because of a defect in manufacturing, marketing, 1 or design. B. Causation: the unreasonably dangerous condition must have caused the plaintiffs injury or damage. The defect must have been a substantial tactor in causing the plaintiff s injury. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS \$402A (1965); Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 381-82. Because the Robins' petion alleges all three forms of strict products liability, we will address each in tum. Manufacturing Defect Under Green law, a plaintiff has a manufacturing defect claim when a frished product deviates, in terms of its construction or quality. from the specifications or planned output in a manner that renders it unreasonably dangerous. Grinnell, 951 S. W. 2d at 434 ; see also Sims v. Washex Mach. Corp., 932 S.W.2d 559,562 . The Robins have produced no evidence at trial with regard to a defective manufacturing process of the specific lighter that caused the acoident. Rather, the Robins vigorously argue that the entire design of all such lighters without chlld-proot features are defective. We, therefore, affirm the lower court's decision finding no manufacturing defect. Marketing Defect (Failure to Warn) A defendant is liable if the lack of adequate warnings or instructions renders an otherwise adequate product unreasonably dangerous. Caterpillar, 911S.W.2d at 382 . The existence of a duty to wam of dangers or instruct as to the proper use of a product is a question of law. Grinnel, 951 S. W.2d at 426. The determination of whether a manulacturer has a duty to wam is made when the product leaves the manufacturer. General Motors Corp. v. Saenz, 873S. W.2d 353, 356. However, there is no duty to wam when the risks associated with a particular product are 'Within the ordinary knowledge common to the community," Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 426 (quoting Joseph E. Seagram 8 Sons, Inc. v. McGuire, 814 S.W2d 385, 388 (no duty to warn of dangers of excessive or prolonged use of alcohol)). As stated by the Green Supreme Court, "the law of products liablity does not require a manufacturer or distributor to wam of obvious risks." Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 382. We perform an objective inquiry when determining if a risk is obvious. Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 383; see also Sauder Custom Fabrication, Inc. v. Boyd. 907 S.W.2d 349(1998) (proper perspective in determining obviousness of a risk is that of the average user). At trial, Jackje Jr.'s mother testified that she did not need a waming to tell her to keep lighters out of the hands of her child. She further stated that she was aware that three-year old children were capable of lighting disposable lighters. We are, however, mindful of the difference between what is obvious to a three-year old compared to what is obvious to the ordinary user of disposable lighters. 1 A defendant's failure to warn when the law requires adequate wamings b a type of marketing defect. Caterpillar. 911 S.W.2d at 382 . The average ordinary consumer of disposable lighters does not need a warning to be appraised of the dangers associated with fire produced from lighters. At the same time, those lacking the mental capability necessary to understand the dangers of fire caused by lighters, e.g. three-year olds, would not otherwise be able to comprehend warnings placed on the lighters. The absence of a warning tabel on this disposable lighter did not make the product unreasonably dangerous. We conclude that as a matter of law, the danger associated with fire produced from a cigarette lighter is an obvious risk within the ordinary knowledge of the community. Therefore, DSI owed no duty to the Robins related to a marketing defect. Defective Design "The duty to design a safe product is an obligation imposed by law." Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 432 (quoting McKisson v. Sales Amilates, Inc., 416 S.W.2d 787, 789. Whether a seller has breached this duty, that is, whether a product is unreasonably dangerous, is a question of fact for the jury. Grinnell, 951S.W.2d at 432. A product is defectively designed when it complies with design specifications, but the design itself causes the product to remain unreasonably dangerous. Sims v. Washex Mach. Corp., 932 S.W.2d 559. 562. Detormining whether a design is unreasonably dangerous requires balancing the utility of the product against the risks involved in its use. Grinnel., 951 S.W.2d at 433; Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 382. The objective is to hold manufacturers of products designed with excessive risks accountable, but at the same time, to protect manufactures of products that are "safe enough." David G. Owen. Toward a Proper Test for Design Defectiveness: Micro-Balancing" Costs and Benefits, 75 TEX. L. REV. 1681, 1665 (1997). This Court has adopted the risk-utility analysis as a means of determining whether a product is defectively designed. 2 See O'Brien v. Muskin Corp., 102 S.W. 181-46 (1985). The analysis requires a jury to impose liability on the manufacturer if the danger posed by the product outweighs the benefits of the way the product was designed and marketed. The analysis imputes knowledge of the danger to the manufacturer, and then asks whether, given that knowledge, a reasonable prudent manufacturer nevertheless would have placed the product on the market. In a design defect case, applying the risk-utility analysis, ovidence of the following factors is admissible: 1. the utility of the product to the user and to the public as a whole weighed against the gravity and likelihood of injury from its use; 2. the manufacturer's ablity to eliminate the unsafe character of the product without seriously impairing is usefulness or significantly increasing its costs. Because defoctiveness of the product in question is determined in relation to safer altematives, the fact that its risks could be diminished easily or cheaply may greatly influence the outcome of the case. Thus, the likely effects of the altematives design on production costs, the effects of the alternative design on product longevity, maintenance, repair, and esthetics are factors that may be taken into account. Whether a product was defectively designed must be judged against the technological context existing at the time of its manufacture. Thus, when the plaintiff allieges that a product was defectively designed because it lacked a specifle feature, attention may become focused on the feasibility of that feature-the capacity to provide the feature without greatly increasing the product's cost or impairing usefulness. This feasibility is a relative, not an absolute, concept, the more scientifically and economically feasible the altemative was, the more likely that a jury. The risk vs. utility analysis concerning design defect is also supported by the festatement (Third) of Torts: Products Llability, Which explicitly adopts a "risk-utility" test as the standard for determining the delectivegess of product designs. AESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TOATS: PAODUCTS LAAEITTY \& 2(b) (Proposed final Draft 1997). may find that the product was defectively designed. A plaintiff may advance the argument that a safer altemative was feasible with evidence that it was in actual use or was available at the lime of manufacture. Feasibility may also be shown with evidence of the scientific and economic capacity to develop the safer altemative. Thus, evidence of the actual use of, or capacity to use, safer altematives is relevant insofar as it depicts the avallable scientific knowledge and the practicalities of applying that knowiedge to a productis design; and 3. the user's anticipated awareness of the dangers inherent in the product and their avoidability because of general public knowledge of the obvious condition of the product, or of the existence of suitable warnings or instructions. See Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 432. At trial, the Robins relied in part on information contained in the Federal Register. From 1980 through 1985 , an estimated 750 persons were injured each year in residential fires started by children playing with lighters. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 53 Fed. Reg. 6833,6836 (1988) These fires caused the death of 120 people each year. Id. The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that the annual cost of fires caused by children playing with lighters was between 300 and 375 million dollars. Id. For the years 1988 through 1990 , the number of deaths caused annually by children playing with lighters had increased to 150 , and the number of injuries had risen to 1,100. Safety Standard for Cigarette Lighters, 58 Fed. Reg. 37,557,37564 (1993) (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. pt. 1210). The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that between 80 and 105 deaths per year would be averted by the implementation of child-proof lighters. Not all casualties would be eliminated because numerous nonchild resistant lighters will remain in consumer circulation. Satety Standard for Cigarette Lighters, 58 Fed, Reg. 37,557,37,564 (1993). By reducing property damage and medical expensos, approximately $205 - $270 million dollars will be saved by the implementation of child-proof disposable lighters. Id. Undoubtedly, manulacturers will incur costs to install chilld safety features. The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that the lighter manufacturing industry will incur initial costs approaching $50 million. Id. at 37,565. In 1993 , the Commission estimated that manufacturers could expect a one to five percent increase in the production cost. Id. The Commission estimated that because most disposable lighters cost 15 to 25 cents to produce, the manufactures would likely see an increase in total per-unit cost at roughly 1 to 5 cents. Id. At trial, Dr. John O. Geremia, a mechanical engineer and an expert in fires associated with disposable Ighters, testified that "The lighter in this case is defective in design in that it has no child resistant feature whatsoever on the Iighter and that such feature would not havo altered the functionality of the product." Evidence at trial demonstrated that no manulacturer of disposable lighters incorporated chid resistant features untill 1992, three years after Jackle Jris injury. Although no chidd resistant lighters were marketed until 1992, Geremia testified that it was technologically possible to produce child proof lighters in 1969. Geremia further stated that manufacturers were aware that chilld resistant features had been established as early as 1972 . In his opinion, these features were not implemented because of manufacturers' resistance. We conclude that DSi had failed to prove that the judgment beiow was manilestly erroneous. There was factual evidence presented at trial that suggests that the product was defectively designed. First, there was amplo evidence indicating that at the time the product was manufactured it was tochnoiogically feasible to incorporate childproof features to the product as the technology became available in the early 1970s. Also, these child proof features wore available at a cost that was not unreasonably expensive (i.e. only one to five percent of total production cost). Also, there was evidence demonstrating that the defendant manufacturer had the ability to eliminate the unsale character of the product by incorporating the childproof feature without seriously impairing the usefulness of the lighter. 7 Moreover, as the record indicates adult users of such lighters are generally aware of the dangers inherent in allowing chlldren to use them. Lastly, ample factual evidence was presented at triat that suggested that the defect was a substantial factor contributing to the injuries sustained by the plaintifle. Had the defendant incorporated the childproof features, the plaintiffs would not have been able to start a fre and sustain the burns she did in fact sustain. Conolusion We affirm the judgment entered against the defendant. Davie L. Wilson, Justice JAMES FISCHER AND GENEVA FISCHER, PLAINTIFFS-RESPONDENTS, V. JOHNS-MANVILUE CORPORATIONS AND BELL ASBESTOS MINES, LTD. DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS A-2430-81T2 A-2942,81T2 Superior Court of Green November 29, 1983, Argued January 31, 1984, Decided COUNSEL: David R. Gross argued the cause for appellants Johns-Manville Corporations Kart Asch argued the cause for respondents James R. Fischer and Geneva Fischer JUDGES: Botter, Pressler and O'Brien. The opinion of the court was delivered by Pressler, J.A.D. OPINION BY: PRESSLER OPINION: This is a strict liability case. Defendants, suppliers of asbestos materials, appeal from a jury verdict awarding compensatory and punitive damages to plaintiff James R. Fischer for the pulmonary disease he suffered as a result of his prolonged exposure to asbestos and awarding compensatory damages to his wife, plaintiff Geneva Fischer, on her per quod claim. The primary issue raised on this appeal is whether punitive damages are recoverable in a products liability action tried on principles of strict liability. Although Green has not yet considered this question, it has been recently addressed by many of our sister states, all of which have concluded that there is no fundamental conceptual or public policy bar to application of customary punitive damages principles in these actions. We agree with this conclusion. We are also satisfied that the punitive damages verdict here rested upon an adequate evidential base and proper instructions from the trial judge. Accordingly. the verdict is affirmed. By the time trial commenced, this multi-party, multi-issue litigation had been significantly reduced in scope. The sole remaining plaintiffs were the Fischers and the sole issue on which they elected to proceed was striot liability based on defendants' failure to warn of health hazards related to exposure to asbestos. The number of defendants had been reduced to two: Johns-Marville, Bell Asbestos Mines, Lid. (Beil). The compensatory verdicis in favor of Mr. and Mrs. Fischer, in the total amount of $86.000 and $ 5,000 respectively, were apportioned by the jury on the basis of 80% against Johns-Manvilie and 20% against Bell. In addition, the jury awarded Mr. Fischer punitive damages against Johns-Manville in the amount of $240,000 and against Bell in the amount of $60,000. From the proofs, the jury could have found that plaintiff James Fischer worked for Asbestos, Ltd. In Passaic County from 1938 through the end of 1942 and for an additional four-month period in 1945. His duties required him to handle asbestos in various forms, causing him regularly to inhale asbestos dust. He never wore any protective clothing or apparatus and was never given any cautionary waming or instruction in the safe handing of asbestos either by his employer or by the suppliers of the asbestos. materials, who were identifled at trial as Johns-Marville and Bell. After leaving Asbestos, Lid., plaintiff was employed both in farm work and in other industrial employmente, none of which involved exposure to substances deleterious to the lungs. Mr. Fischer's pulmonary disease frst manifected itself in 1977 when it was detemined that he was suffering from asbestos-related problems. He was placed on medication which ultimately led to such side effects as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis. in 1979 he was hospitalized suffering from bronchitis with borderine pnoumonia but was eventually able to retum to work. in fobruary 1980 he had a heart atteck and has been unable to work since that time. He was then 61 years old. His total disability was attributed by his treating physician as 30% due to chronic obstructive lung disease due to smoking. 60% due to asbestos exposure and the side effects of the medication he took to alleviate those puimonary problems, and 10% due to the heart condition. There is no doubt from this record that plaintiff proved a strict liability action against both delendants based on their failure to wam of the hazards of prolonged exposure to asbestos. See Beshada v. JohnsManville Products Corp., 90 N.J. 191 (1982). Thus, the compensatory damages award is not substantially in issue. Johns-Manville and Bell do not challenge it at all. It was the holding of Beshada that a supplier of asbestos could not, by relying on the "state of the art," be relieved of the consequences of his fallure to wam because of his lack of knowledge of the danger of the product at the time of its distribution. Here the issue was not state of the art but actual knowledge, the essential controversy being whether these defendants did in fact have knowledge of the hazards of asbestos during the time of plaintiffs exposure some 45 years ago. Plaintiffs based their punitive damage claim on the contention that defendants knew of these hazards as early as the 1930 s and had made a conscious business decision to withhold this information from the public. They claimed that defendants, with full knowledge of the risks, deliberately chose not to give those warnings to users of the product Which might have enabled them to obtain protection from prolonged exposure. This conduct, plaintitts alleged, constituted an outrageous and fagrant disregard of the substantial health risks to which defendants subjected the public and justified the imposition of punitive damages. The jury evidenty agreed. Our review of the record satisfies us that there was substantial proof adduced to support these factual contentions and the jury's acceptance of them. The proofs respecting Johns-Marville were, indeed, overwheiming. Johns-Marville, in its answers to interrogatories, which were read to the jury, admitted that [t]he corporation became aware of the relationship between asbestos and the disease known as asbestosis among workers imvolved in mining. milling and manufacturing operations and exposed to high levels of virtually 100% raw asbestos fibers over long periods of time by the earty 1930 . The corpocation has followed and become aware of the general state of the medical art relative to asbostos and its relationship to disease processes, if any. In response to plaintiff's' requests for admissions, also read to the jury, it admitted that in the earty 1940 's it knew that asbestos "was dangerous to the health" of those industrial workers who were exposed to excessive amounts of the material. Plaintiffs, moreovor, produced as a witness Dr. Daniel C. Braun, president of the Industrial Health Foundation, a research organization which develops, accumulates and disseminates information about occupational diseases. Dr. Braun testified that Johns-Manville has been a member of the Foundation since 1936. He also testified that since 1937 the Foundation has sent to its members a monthly digest of articles appearing in scientific joumais which relate to occupational disease. Relevant portions of the digests, which were admitted into evidence, included relerences to eleven soientific articles published between 1936 and 1941 documenting the grave pulmonary hazards of exposure to asbestos and discussing measures which could be taken to protect workers. On appeal, neither Bell nor Johns-Manville challenges either the amount of the punitive damages allowed or the trial judge's instructions respecting the standards which the jury was to apply in considering an award of punitive damages. Their challenge is rather based on the contensions first, that punilive damages are not allowable at all in product liability actions and, second, that even if they are, the proots in respect of each were inedequate to meet the necessary standard of outragbous conduct in deliberate disregard of the rights of others. We have considered these contentions and are constrained to reject them both. As to the first, we conclude that in an appropriate case, punittve damages may be awarded in a product liablity action based on strict liablity. It is well settied in this jurisdiction that while damages in tort actions are generaly intended only to compensate, nevertholess punilive damages are allowable in exceptional and egregious instances for the purpose of punishing the tortieasor and deterring both him and others from like conduct. The standard of egregiousness usually implies that there has been a delberate act or omission with knowledge of a high degree of probability of harm and reckless indifference to consequences." Berg v. Reaction Motors Di., 37 GD. 396, 414 (1962). In cases dealing 10 with products, it has been uniformly concluded that punitive damages will lie when a manufacturer has knowledge, whether or not suppressed, that his product poses a grave risk to the health or salety of its users and fails to take any protective or remedial action. See, e.g., Leichtamer v. American Corp., supra, 424 N.E.2d at 5789. With respect to the public policy considerations implicated in allowing punitive damages in products liability cases, we concur with the judicial consensus that if punitive damages are awarded only in egregious situations, the public interest, on balance, is better served by allowing such an award than by precluding it. As we have noted, the underlying purpose of punitive damages is both to punish the offender and to deter him and others from engaging in similar conduct. Both punishment and deterrence are appropriate responses to a supplier of defective goods who has knowledge of the high degree of rigk of grave harm to which they will subject the public but who nevertheiess makes the cynical, conscious business decision to place and keep them on the market. Were punitive damages to be withheld, those entrepreneurs who act with flagrant disregard of the public safety would be able to write off the public's injury as a cost of doing business by the payment of compensatory damages, for which there is typically insurance coverage. One court has described this practice as the "coldblooded calculation" that it is more profitable to pay claims than to cure the defect. See Campus Sweater & Sportswear v. M. B. Kahn Const., supra, 515 F.Supp. at 106-107. Thus, it is only the threat of punitive damages which can ultimately induce these entrepreneurs and others to act with a reasonable modicum of responsibility. Although "fcjonsiderable concern has surfaced in recent decades over the effect of multiple punitive damages awards on a single defendant faced with mass litigation," nevertheless the "financial interests of a wanton wrongdoer must be considered in the context of societal concem for the injured and the future protection of society." State ex rel. Young v. Crookham, supra, 618 P.2d at 1270. Having determined that punitive damages are allowable, we address the contention of each of the defendants that there was insulficient proof of such egregious conduct to support the imposition of punitive damages in this case. We have no doubt, however, that plaintiffs' proofs justified the jury's evident conclusion that irrespective of whatever remedial efforts may have been taken by the asbestos industry years later, both defendants, during the period of plaintiffs exposure, acted knowingly and deliberately in subjecting him as an asbestos worker to serious health hazards with utter and reckless disregard of his safety and well-being. It is indeed appalling to us that Johns-Manville had so much information on the hazards to asbestos workers as early as the mid-1930's and that it not only failed to use that information to protect these workers but, more egregiously, that it also attempted to withhold this information from the public. It is also clear that even though Johns-Manville may have taken some remedial steps decades ago to protect its own employees, it apparently did nothing to warn and protect those who, like plaintiff, were employed by Johns-Manville customers engaged in the manufacture and fabrication of asbestos products. We are satisfied that that conduct met the standard of egregiousness which must underlie a punitive damages award. The jury here was justified in concluding that both defendants, fully appreciating the nature, extent and gravity of the risk, nevertheless made a conscious and coldblooded business decision, in utter and flagrant disregard of the rights of others, to take no protective or remedial action. The judgment appealed from is affirmed in its entirety. Green Commerclal Code $2719. Contractual modification or limitation of remedy (1) Subject to the provisions of subdivisions (2) and (3) of this section, (a) The agreement may provide for remedies in addition to or in substitution for those provided in this division and may limit or alter the measure of damages recoverable under this division, as by limiting the buyer's remedies to retum of the goods and repayment of the price or to repair and replacement of nonconforming goods or parts; and (b) Resort to a remedy as provided is optional unless the remedy is expressly agreed to be exclusive, in which case it is the sole remedy. (2) Where circumstances cause an exclusive or limitod remedy to fail of its essential purpose, remedy may be had as provided in this code. (3) Consequential damages may be limited or excluded unless the limitation or exclusion is unconscionable. Limitation of consequential damages for injury to the person in the case of consumer goods is generally viewed unconscionable and hence invalid. Write a report to the upper management of Green Cast inc. that explains what happened in the First.Class product line. Use the report writing guide from the course website. Explain the decision made and the basis of the decision. To support your conclusions in the report. perform the analysis and answer these questions: Q. 1. Prepare a budgeted inceme statement for Oven-Safe Classic for 2017 if the engineers' redesign elforts had worked as originally planned. Use these assumptions:- a. First quarter sales of 1,500,000 units will be achieved each quartet in 2017 . b. The selling peice for 2017 will remain 11% below the price charged from 2012 . 2016 , and there were no sales price increases during the 2012-2016 period. c. The variable cost of goods sold averaged about $5.55 per unit of ovenware from 20122016. d. Vasiable production costs will be reduced by 36% due to the new design. e. The fixed oost of production in 2016 contained one-time, increased costs (about $4,000,000 ) for the design changes. For 2017, fixed costs are expected to be about 3.6% higher than in 2015 . f. Marketing costs contain both fised and variable elements, however, it is budgeted based on spending 7.1% of expecied sales revenue. 9. Oher fixed costs are expected to increase about 2.6% over 2016. Would the product manager have met his prost target of 25% return on saies in 2017 for the product line with the redesign? Q. 2. Prepare the budgeted 2017 income stetement for Oven.Safe Classic that the producfion, quality, and product managers consodered whien they discussed the frst option avallable to them. a. Under that opton, the shipment would be delayed and about one third of the year's sales of 6.000,000 unite would be lost. b. The product would be sold at the 11 price reduction but produced under the old cost structure for six months (variable production costs of $5.55 per unit). Afler sox months, the variable cost savings of 36% would be achieved. c. Assume that recycling the current production would add $500,000 to the foced production coets originnlly budgeted for 2017. In additon, the product line witt incur an additonal $2,000,000 in design eng neering to polve the problem within a 6-month period (this will huvolve the use of overtine and conesitionts). d. Other coer tems would stay as orninally busgoted for 2017 . What would the product ine's proff be under this altecrative? What would the retum on sales for the product line be? Q.3. The production, quality and product managers considered their second option to be producing and selling flawed units for 6 months while engineers corrected the problem. Under this option, the company would not disclose the problem and hope for the best. Perhaps none of the product claims would involve any injury, only product replacement would be required at a cost of about $12 per unit. a. Adjust the 2017 budget for an assumed defect rate of 25% during the first 6 months of production. (Note this is a defect rate in addition to the nomal rate faced in each year, 2012-2016, which is already accounted for in marketing cost) b. Adjust the fixed production cost for 2017 for an additional $2,000.000 in design engineering to solve the problem within a 6-month period. (This will involve the use of overtime and consultants). What would the budgeted profit and retum on saies be if option two were tielected? Q. 4. Assume Mrs. Rio has filed a suit against Green Cast Products inc. for the injuries that she sustained under the theory of strict product liability in tort. Assume further that Mrs. Rio would prevail in a cause of action against Green Cast Products Inc. under strict product liability in tort. Is she likely to recover punitive damages? Q. 5. Based on your knowledge of ethics indicate if you think the engineer who finally reported that the original tests had been altered acted ethically, In your answer consider which stakeholders were affected by the engineer's decision and what ethical guldeline was used in the decision. Q. 6. What changes would you recommend to Kitchen Essential that would help them to prevent these kinds of problems from recurring? Consider their goals, internal structures. competencies and actlities in your answer. GREEN CAST, INC. Green Cast, Inc. produces and sells a line of ovemware (Oven-Sate Classic) that goos from oven (conventional or microwave) to the refigerator without breaking. Its design is functional, yet attractive enough to both cook and serve food. The overware liems are sold through gourmet shops, such as William Sonoma, and major department stores, such as Macy's and Bloomingdale's, Due to an economic downturn, sales through gourmet shops and department stores heve lapged expectations for the past two years. This has kept the product manager of the Oven-5afe Classic from moeting his required target of producing a 2.5% retum on sales of the product. This return is measured by preparing an income statement containing the sales of this product less any expenses considered attibutable to this product line. An attrbutable expense exists to benefit the product line. It is a cost that would be avoided if the product line were discontinued. Further, when calculating the required 25% return on sales, the product line profitability statement does not deduct any allocations for general and administrative costs. Exhibit 1 provides a product income statement for this line for the past 5 years. In an eflort to increase sales, design engineers modified the ovenware product slightly in 2016 . They made it less expensive to produce (saving about 36% of variable production costs) but indistinguishable in looks and functionality from the original product. The modfied product also resulted in increased product longevity of about 10%. The product manager, excited about the modifications and cost savings, lowered the price by 11% and presented the item at a national food industry show at the end of 2016 . He proudly advertieed the product as having exactly the same looks, safety features, and functionality as the original product. He offered the same product warranty of six months under normal use conditions. He then booked sales of 1,500,000 pleces to existing customers for the first quarter detvery. Production commenced immediately to fin these first-quarter orders. During routine quality testing in production, personnel discovered a serious problem with the product. The overware, under a small range of extremely high cooking temperatures ( 450500 degrees), would explode if set on a cold trivet or placed in the reirigerator. The explosion could potentially cause the person holding the ovenware to suffer serious cuts and substantial, permanent burns. Unfortunately, the seriousness of the problem was not known until after the production of the 1,500,000 pieces was nearty completed. Basod on statistical testing. it appeared that the flaw only occurs about .25 percent of the time (one quarter of a percent). The production, quality, and product managers met to discuss this issue. They felt that they had only two options. First, they could delay shipment, recycle the current production, and produce the original overware using old methods. Of course, the product would have to be sold at the 11% price reduction while being produced with the old cost structure for sbx months. Customers would experience about a thirty-day delay in delivery and it is lkely some would be so annoyed that they would cancel their orders. The product manager estimated that about one-third of the year's orders would be lost. In addibon, this would likely cause those customers to be permanently lost to competitors. At the conciusion of the six months period, the problem would be solved, and the product would achiave the 36% variable cost savings. Second, they could ship the goods without calling attention to the problem and hope for the best. They would simply act surprised if any problem arose and pay for damages. With only a 25 percent (.0025) fallure rate and only under a small range of temperatures, the risk of the flaw soemed quite small. Furthor, since the product exploded when set on a cold surface, perhaps no person would actually be hurt and the damages would be limited to broken ovemware replacement. Under exther altemative, production engineers would work on correcting the problem. Engineers folt that they could solve the problem by the end of the second quarter. If the first option were taken, 1 meant 6. monthe of old production under new reduced sales prices plus scrapping the existing flawed units. Under the second option, it meant 6 months of producing and selling flawed. new products. Then the problem would be corrected. The managers decided that the risk of option two was worth taking and shipped the flawed products (without disclosing the potential hazards). They toned down the quality testing report results such that it appeared that the product might only crack (not explode). Within two months of shipment, things went well. Only 1,575 product claims were made, and none involved personal injury. Replacement items were provided and customers remained satisfied. In the third month, a disaster occurred. Mrs. Rio organized a goodbye party for her son before he went away to college. She prepared her son's favorite chicken and rice dish and cooked it in her oven using the new Oven-Safe Classic that she bought from her local department store. She cooked it at 475 degrees for about two hours and when it was ready, she then placed it in the refrigerator. As the ovenware was placed in the refrigerator, it exploded, spraying glass and hot contents on Mrs. Rio. A glass fragment struck her in the eye. Mrs. Rio also suffered second and third-degree burns on her face, neck, and arms. The accident was reported in newspapers while the department store began investigating its cause. Managers at Green Cast, Inc. acted surprised when contacted by the department store's manager. The product manager of Oven-Safe Classic answered questions regarding the product. He provided the altered quality report to the department store's manager and continued to sell the product while the engineers worked on a solution to the problem. Meanwhile, several other serious explosions occurred, and other people were seriously hurt. Finally, a quality engineer from Green Cast hired an attomey, met with a newspaper reporter, and disclosed that the original test results had been altered. The company was forced to recall all products and halt production. Required Write a report to the upper management of Green Cast, Inc. that explains what happened in the OvenSafe Classic line. Use the report writing guide from the course website. Explain the decision made and the basis of the decision. To prepare for this case, you may want to review managerial accounting LDC concepts 2, 5 and 8; financial accounting concept 9 ; and business law concepts 2 and 9 . EXHIBIT ONE Green Cast, Inc. Oven-Safe Classic Product Income Statement For the years ended December 31, 2012-2016 GREEN CAST, INC. LIBRARY DIRECT SOURCE INTERNATIONAL, INC Appellant v. RHONDA RENA ROBINS, INDNDUALLY AND AS NEXT FRIEND OF JACKE WAYNE ROBINS, JR., A MINOR, AND JACKIE WAYNE ROBINS, SR. Appellees NO. 01-96-01185-CV COURT OF APPEALS OF GREEN, FIRST DISTRICT, HOUSTON July 30, 1998, Date of Opinion July 30, 1998, Opinion lssued PRIOR HISTORY: [** 1] COUNSEL: Stephen F. Malout, Dallas, FOR APPEUANT. Charles W. Seymore, Sugariand, Craig Muessig, Baytown, Evelyn T. Alts, Houston, FOR APPELLEES. JUDGES: Davie L. Wilson, Justice. Panel consists of Chief Justice Schneider and Justices Wison and Nuchia. OPINION BY: Davie L. Wiison OPINION: Appellant, Direct Source Intemational, Inc. ("DSI"), appeals a judgment rendered in favor of appellees, Rhonda Rene Robins, individually and as next friend of Jackie Wayne Robins, Jr., a minor, and Jackie Wayne Robins, Sr. (sometimes collectively relerred to as the "Robins"). Factual and Procedural Background On August 11, 1989, Jackie Wayne Robins, Jr., then three years old, set fre to a plle of clothes with a disposable cigaretle lighter allegedly placed in the stream of commerce by DSi, the manufacturer. The clothes and the lighter were in a van outside his parent's home. As a result of the fire, Jackie Jr. sulfered severe and lasting injuries. Among others, Robins sued DSi for strict product leability in tort aleging defects in the manufacturing. markesing. and design of the Sighter. The primary basis for the Robins' claims was that the lighter did not include a child-proofing or child-resistant design or mechanism to eliminate or reduce the risk that a child such as Jackie Jr. could ignite the lighter. DSI argued at trial that in 1989 there was no duty on the manutacturer to make lighters child-resistant because they were in a certain class of products intended for adult use and not otherwise detective. The Robins argued Green law holds a manufacturer legally responsible for marketing a product not reasonably safe for the products intended use and foreseeable misuse as designed. The judge entered a judgment in tavor of Robins and DSI now appeals. DSi argues a judgment was improperly granted against it because DSi has not produced a defective product. Discussion 4 In Green, a plaintirt injured by an allegedly defective product may seek recovery against the manufacturer on the basis of any one or more of four theories of liability. Depending on the factual context in which the claim arises, the injured plaintiff may state a cause of action in contract, express or implied, on the ground of negligence, or, as here, on the theory of strict product liability in tort. Green courts have adopted the theory of strict products liability expressed in section 402A of the Restatement (Second) of Torts. See American Tobacco Co. V. Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d 420,426 (Green. 1997): Caterpillar, Inc. V. Shears, 911 S.W.2d 379, 381 (Green. 1995). Section 402A provides that any person engaged in the business of sciling products for use or consumption, may be held strictly liable for injuries to the user or consumer of such product, as long as: A. Product was defective: Liability is imposed for products sold "in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer. A product may be unreasonably dangerous because of a defect in manufacturing, marketing, 1 or design. B. Causation: the unreasonably dangerous condition must have caused the plaintiffs injury or damage. The defect must have been a substantial tactor in causing the plaintiff s injury. RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF TORTS \$402A (1965); Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 381-82. Because the Robins' petion alleges all three forms of strict products liability, we will address each in tum. Manufacturing Defect Under Green law, a plaintiff has a manufacturing defect claim when a frished product deviates, in terms of its construction or quality. from the specifications or planned output in a manner that renders it unreasonably dangerous. Grinnell, 951 S. W. 2d at 434 ; see also Sims v. Washex Mach. Corp., 932 S.W.2d 559,562 . The Robins have produced no evidence at trial with regard to a defective manufacturing process of the specific lighter that caused the acoident. Rather, the Robins vigorously argue that the entire design of all such lighters without chlld-proot features are defective. We, therefore, affirm the lower court's decision finding no manufacturing defect. Marketing Defect (Failure to Warn) A defendant is liable if the lack of adequate warnings or instructions renders an otherwise adequate product unreasonably dangerous. Caterpillar, 911S.W.2d at 382 . The existence of a duty to wam of dangers or instruct as to the proper use of a product is a question of law. Grinnel, 951 S. W.2d at 426. The determination of whether a manulacturer has a duty to wam is made when the product leaves the manufacturer. General Motors Corp. v. Saenz, 873S. W.2d 353, 356. However, there is no duty to wam when the risks associated with a particular product are 'Within the ordinary knowledge common to the community," Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 426 (quoting Joseph E. Seagram 8 Sons, Inc. v. McGuire, 814 S.W2d 385, 388 (no duty to warn of dangers of excessive or prolonged use of alcohol)). As stated by the Green Supreme Court, "the law of products liablity does not require a manufacturer or distributor to wam of obvious risks." Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 382. We perform an objective inquiry when determining if a risk is obvious. Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 383; see also Sauder Custom Fabrication, Inc. v. Boyd. 907 S.W.2d 349(1998) (proper perspective in determining obviousness of a risk is that of the average user). At trial, Jackje Jr.'s mother testified that she did not need a waming to tell her to keep lighters out of the hands of her child. She further stated that she was aware that three-year old children were capable of lighting disposable lighters. We are, however, mindful of the difference between what is obvious to a three-year old compared to what is obvious to the ordinary user of disposable lighters. 1 A defendant's failure to warn when the law requires adequate wamings b a type of marketing defect. Caterpillar. 911 S.W.2d at 382 . The average ordinary consumer of disposable lighters does not need a warning to be appraised of the dangers associated with fire produced from lighters. At the same time, those lacking the mental capability necessary to understand the dangers of fire caused by lighters, e.g. three-year olds, would not otherwise be able to comprehend warnings placed on the lighters. The absence of a warning tabel on this disposable lighter did not make the product unreasonably dangerous. We conclude that as a matter of law, the danger associated with fire produced from a cigarette lighter is an obvious risk within the ordinary knowledge of the community. Therefore, DSI owed no duty to the Robins related to a marketing defect. Defective Design "The duty to design a safe product is an obligation imposed by law." Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 432 (quoting McKisson v. Sales Amilates, Inc., 416 S.W.2d 787, 789. Whether a seller has breached this duty, that is, whether a product is unreasonably dangerous, is a question of fact for the jury. Grinnell, 951S.W.2d at 432. A product is defectively designed when it complies with design specifications, but the design itself causes the product to remain unreasonably dangerous. Sims v. Washex Mach. Corp., 932 S.W.2d 559. 562. Detormining whether a design is unreasonably dangerous requires balancing the utility of the product against the risks involved in its use. Grinnel., 951 S.W.2d at 433; Caterpillar, 911 S.W.2d at 382. The objective is to hold manufacturers of products designed with excessive risks accountable, but at the same time, to protect manufactures of products that are "safe enough." David G. Owen. Toward a Proper Test for Design Defectiveness: Micro-Balancing" Costs and Benefits, 75 TEX. L. REV. 1681, 1665 (1997). This Court has adopted the risk-utility analysis as a means of determining whether a product is defectively designed. 2 See O'Brien v. Muskin Corp., 102 S.W. 181-46 (1985). The analysis requires a jury to impose liability on the manufacturer if the danger posed by the product outweighs the benefits of the way the product was designed and marketed. The analysis imputes knowledge of the danger to the manufacturer, and then asks whether, given that knowledge, a reasonable prudent manufacturer nevertheless would have placed the product on the market. In a design defect case, applying the risk-utility analysis, ovidence of the following factors is admissible: 1. the utility of the product to the user and to the public as a whole weighed against the gravity and likelihood of injury from its use; 2. the manufacturer's ablity to eliminate the unsafe character of the product without seriously impairing is usefulness or significantly increasing its costs. Because defoctiveness of the product in question is determined in relation to safer altematives, the fact that its risks could be diminished easily or cheaply may greatly influence the outcome of the case. Thus, the likely effects of the altematives design on production costs, the effects of the alternative design on product longevity, maintenance, repair, and esthetics are factors that may be taken into account. Whether a product was defectively designed must be judged against the technological context existing at the time of its manufacture. Thus, when the plaintiff allieges that a product was defectively designed because it lacked a specifle feature, attention may become focused on the feasibility of that feature-the capacity to provide the feature without greatly increasing the product's cost or impairing usefulness. This feasibility is a relative, not an absolute, concept, the more scientifically and economically feasible the altemative was, the more likely that a jury. The risk vs. utility analysis concerning design defect is also supported by the festatement (Third) of Torts: Products Llability, Which explicitly adopts a "risk-utility" test as the standard for determining the delectivegess of product designs. AESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF TOATS: PAODUCTS LAAEITTY \& 2(b) (Proposed final Draft 1997). may find that the product was defectively designed. A plaintiff may advance the argument that a safer altemative was feasible with evidence that it was in actual use or was available at the lime of manufacture. Feasibility may also be shown with evidence of the scientific and economic capacity to develop the safer altemative. Thus, evidence of the actual use of, or capacity to use, safer altematives is relevant insofar as it depicts the avallable scientific knowledge and the practicalities of applying that knowiedge to a productis design; and 3. the user's anticipated awareness of the dangers inherent in the product and their avoidability because of general public knowledge of the obvious condition of the product, or of the existence of suitable warnings or instructions. See Grinnell, 951 S.W.2d at 432. At trial, the Robins relied in part on information contained in the Federal Register. From 1980 through 1985 , an estimated 750 persons were injured each year in residential fires started by children playing with lighters. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 53 Fed. Reg. 6833,6836 (1988) These fires caused the death of 120 people each year. Id. The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that the annual cost of fires caused by children playing with lighters was between 300 and 375 million dollars. Id. For the years 1988 through 1990 , the number of deaths caused annually by children playing with lighters had increased to 150 , and the number of injuries had risen to 1,100. Safety Standard for Cigarette Lighters, 58 Fed. Reg. 37,557,37564 (1993) (to be codified at 16 C.F.R. pt. 1210). The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that between 80 and 105 deaths per year would be averted by the implementation of child-proof lighters. Not all casualties would be eliminated because numerous nonchild resistant lighters will remain in consumer circulation. Satety Standard for Cigarette Lighters, 58 Fed, Reg. 37,557,37,564 (1993). By reducing property damage and medical expensos, approximately $205 - $270 million dollars will be saved by the implementation of child-proof disposable lighters. Id. Undoubtedly, manulacturers will incur costs to install chilld safety features. The Consumer Product Safety Commission estimated that the lighter manufacturing industry will incur initial costs approaching $50 million. Id. at 37,565. In 1993 , the Commission estimated that manufacturers could expect a one to five percent increase in the production cost. Id. The Commission estimated that because most disposable lighters cost 15 to 25 cents to produce, the manufactures would likely see an increase in total per-unit cost at roughly 1 to 5 cents. Id. At trial, Dr. John O. Geremia, a mechanical engineer and an expert in fires associated with disposable Ighters, testified that "The lighter in this case is defective in design in that it has no child resistant feature whatsoever on the Iighter and that such feature would not havo altered the functionality of the product." Evidence at trial demonstrated that no manulacturer of disposable lighters incorporated chid resistant features untill 1992, three years after Jackle Jris injury. Although no chidd resistant lighters were marketed until 1992, Geremia testified that it was technologically possible to produce child proof lighters in 1969. Geremia further stated that manufacturers were aware that chilld resistant features had been established as early as 1972 . In his opinion, these features were not implemented because of manufacturers' resistance. We conclude that DSi had failed to prove that the judgment beiow was manilestly erroneous. There was factual evidence presented at trial that suggests that the product was defectively designed. First, there was amplo evidence indicating that at the time the product was manufactured it was tochnoiogically feasible to incorporate childproof features to the product as the technology became available in the early 1970s. Also, these child proof features wore available at a cost that was not unreasonably expensive (i.e. only one to five percent of total production cost). Also, there was evidence demonstrating that the defendant manufacturer had the ability to eliminate the unsale character of the product by incorporating the childproof feature without seriously impairing the usefulness of the lighter. 7 Moreover, as the record indicates adult users of such lighters are generally aware of the dangers inherent in allowing chlldren to use them. Lastly, ample factual evidence was presented at triat that suggested that the defect was a substantial factor contributing to the injuries sustained by the plaintifle. Had the defendant incorporated the childproof features, the plaintiffs would not have been able to start a fre and sustain the burns she did in fact sustain. Conolusion We affirm the judgment entered against the defendant. Davie L. Wilson, Justice JAMES FISCHER AND GENEVA FISCHER, PLAINTIFFS-RESPONDENTS, V. JOHNS-MANVILUE CORPORATIONS AND BELL ASBESTOS MINES, LTD. DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS A-2430-81T2 A-2942,81T2 Superior Court of Green November 29, 1983, Argued January 31, 1984, Decided COUNSEL: David R. Gross argued the cause for appellants Johns-Manville Corporations Kart Asch argued the cause for respondents James R. Fischer and Geneva Fischer JUDGES: Botter, Pressler and O'Brien. The opinion of the court was delivered by Pressler, J.A.D. OPINION BY: PRESSLER OPINION: This is a strict liability case. Defendants, suppliers of asbestos materials, appeal from a jury verdict awarding compensatory and punitive damages to plaintiff James R. Fischer for the pulmonary disease he suffered as a result of his prolonged exposure to asbestos and awarding compensatory damages to his wife, plaintiff Geneva Fischer, on her per quod claim. The primary issue raised on this appeal is whether punitive damages are recoverable in a products liability action tried on principles of strict liability. Although Green has not yet considered this question, it has been recently addressed by many of our sister states, all of which have concluded that there is no fundamental conceptual or public policy bar to application of customary punitive damages principles in these actions. We agree with this conclusion. We are also satisfied that the punitive damages verdict here rested upon an adequate evidential base and proper instructions from the trial judge. Accor

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started