Please complete the discussion questions on page 154. Thanks 13 Revenue Management in Visitor Attractions: A Case Study of the EcoTech Centre, Swaffham, Norfolk Julian

Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

54 users unlocked this solution today!

Please complete the discussion questions on page 154. Thanks

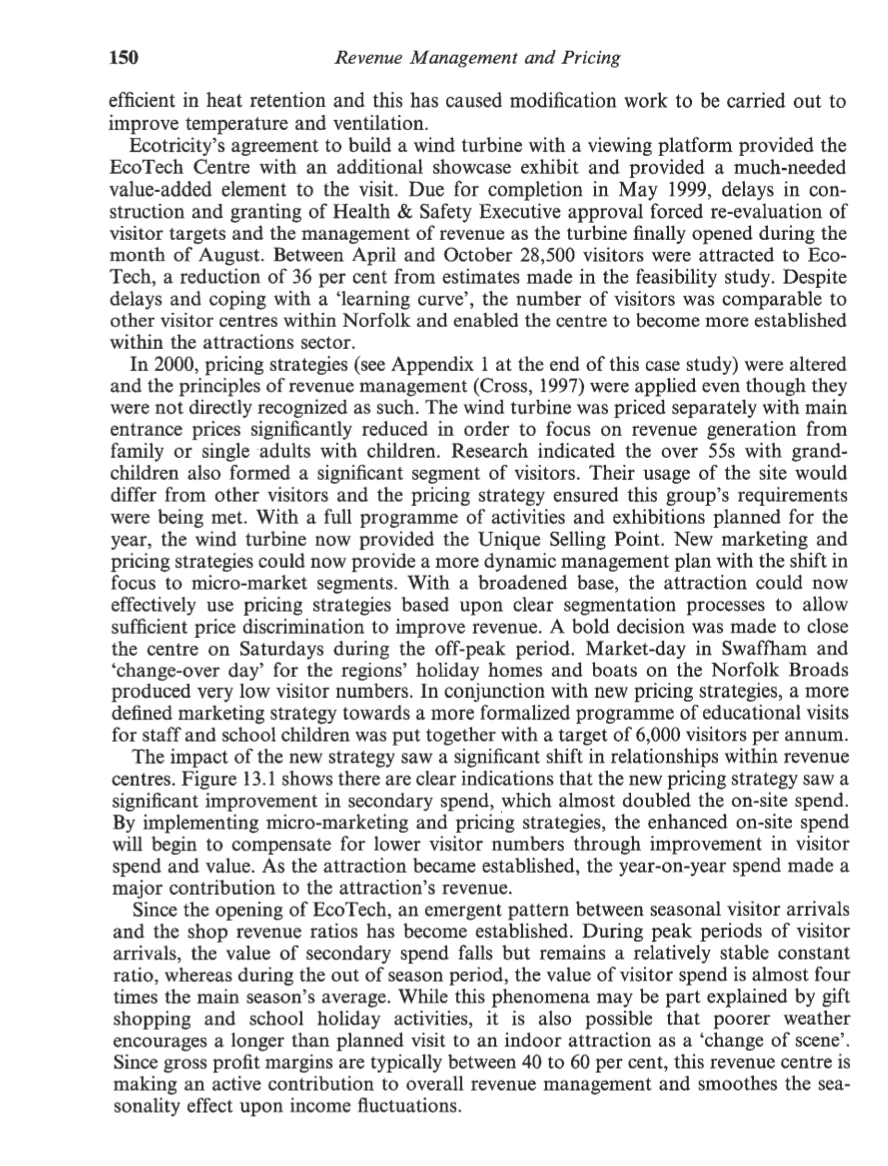

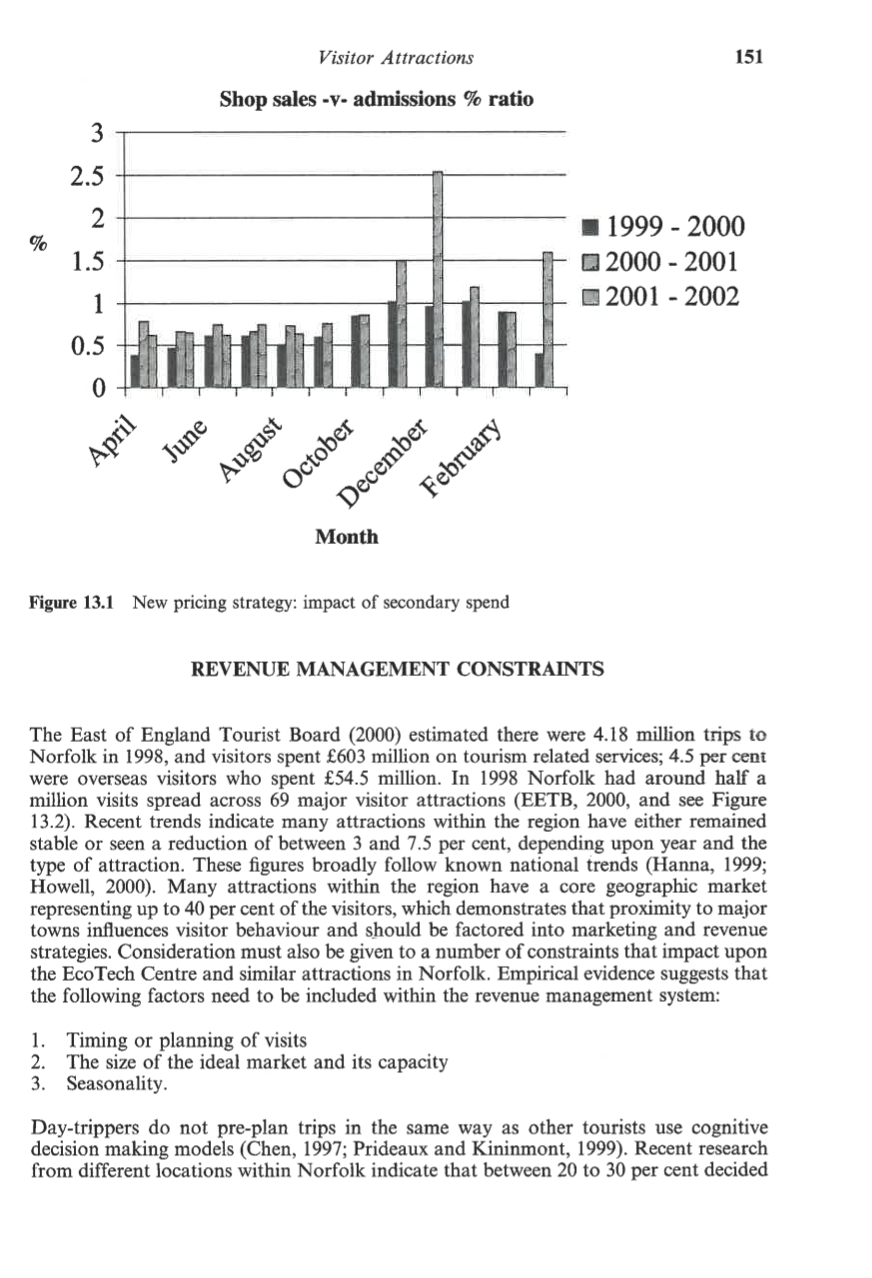

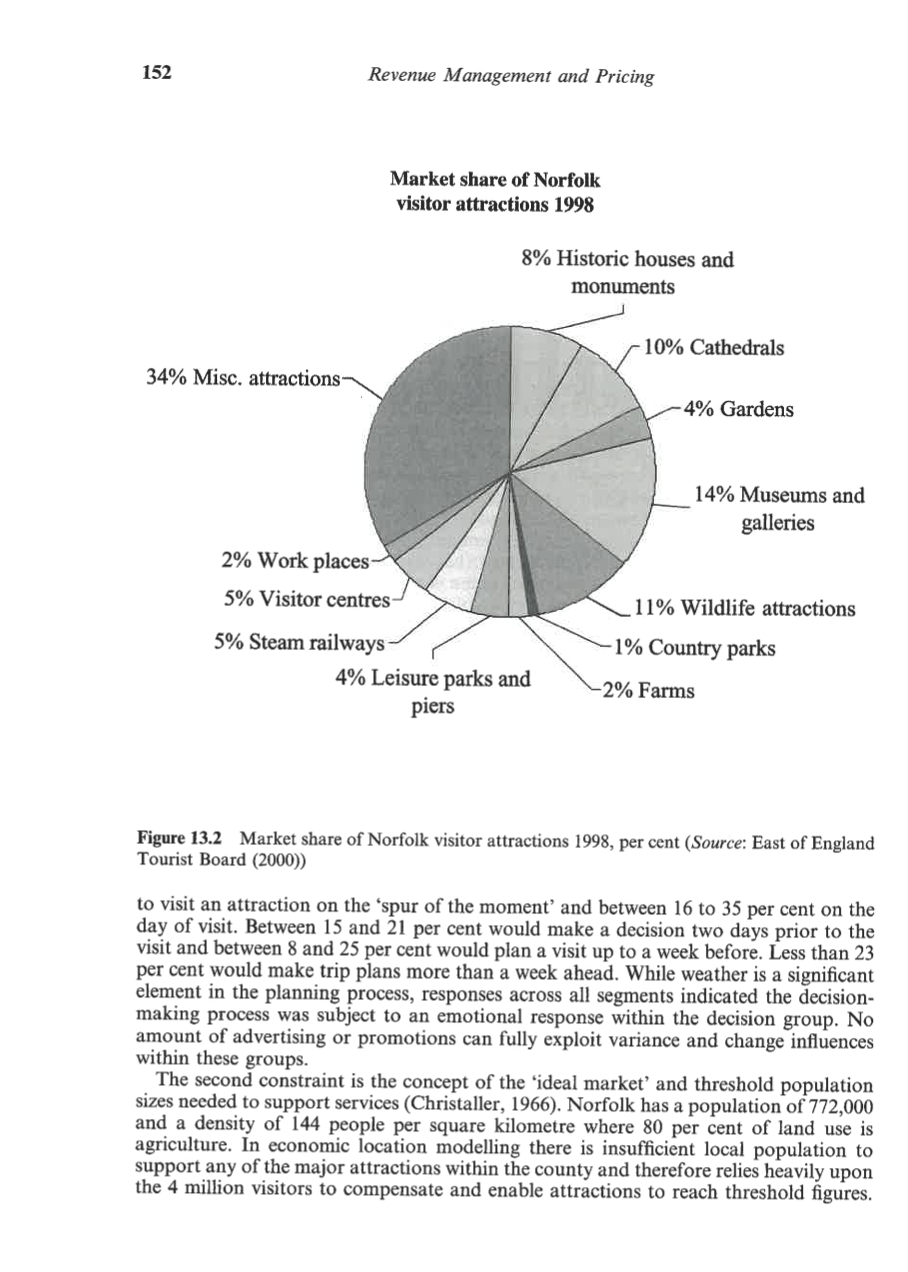

13 Revenue Management in Visitor Attractions: A Case Study of the EcoTech Centre, Swaffham, Norfolk Julian Hoseason INTRODUCTION Visitor attractions form an integral part of the total tourism product for both the domestic and incoming visitors to a region. Attractions cover a broad spectrum of activities based upon the natural or man-made environment ranging from heritage sites through to purpose built centres usually devoted to leisure and recreational activities (Getz, 1993; Swarbrooke, 1999; Hall and Page, 1999). The attractions sector is complex in definition and provides different levels of engagement with the visitor when the encounter takes place (Crouch, 1999). While visitors enjoy this variety, attractions offer an intangible experience (Yeoman and Leask, 1999), which makes visitor man- agement and marketing complex (Prentice et al., 1998) since seasonality and a spatial element enter into the pricing strategy. In the mid-1990s Norfolk was experiencing a decline in its agricultural base and indicators suggested alternative strategies needed implementation to avoid unemploy- ment and social blight in the community of Swaffham. Regional funding from the European Union enabled an imaginative proposal for the development of a sustainable attraction to act as a growth-pole for inward investment. The EcoTech Centre was to be an experimental showcase in design and construction techniques with the emphasis upon environmental management and education. As an attraction, the EcoTech Centre would need to reach a critical mass of around 50,000 visitors per annum to be viable. The centre would be competing against the region's existing attractions, the coast and an area of wetland known as the 'Norfolk Broads'. As the implementation of revenue management matures across the travel and tourism industry, the resultant benefits must make the implementation or adoption a basic management strategy. Research indicates that the attractions sector has yet to Revenue Management and Pricing 144 extensively adopt revenue management as a management technique, therefore this sector produces lower financial performance figures compared to other sectors. Research by Yeoman and Leask (1999) into heritage visitor attractions indicated thar the highly seasonal nature of the market necessitated revenue management techniques being applied to main season activities with more specialist activities being introduced during low or out of season periods for maximization of revenue. However, major capital projects funded by the UK's National Lottery, may have caused distortion to the attractions sector at local, regional and national level where sudden increases in market capacity cannot be met by corresponding increases in visitor activity. Over 1.2 billion has been awarded to over 180 major projects with an additional 2.8 billioa being awarded through European funded grants for projects (Anon, 2000). Key pro- jects like the Royal Armouries in Leeds, and the Earth Centre, failed to live up te projections not only of visitor numbers but also in revenue management where over- estimates and losses threatened their future (McClarence, 2000). For the EcoTech Centre, its future success may not simply lie in developing a highly innovative attrac- tion, but consideration of micro-market behaviour in relation to the capacity of the 'ideal market or catchment area characteristics. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES The aim of this case study is to demonstrate how simple revenue management tech- niques encourage visitors spend in higher profit earning centres within an attraction The objectives are to: 1. Evaluate the impact of a high profile attraction in the attractions market. 2. Evaluate the relationship between pricing and revenue strategies. 3. Analyze the relationship between attractions design and critical mass in attracting visitor numbers. BACKGROUND The Eco Tech Centre has been built on a brownfield site on the edge of Swaffham, a market town in the centre of Norfolk. Sited on a former derelict firework factory, the project aimed at cleaning up a polluted site for the benefit of the community. The original proposal envisaged an experimental building in terms of design and com struction techniques, attracting 50,000 visitors annually, and providing an interactive learning centre based on environmental education. By targeting the enhancement of leisure and tourism facilities it was hoped to attract high inward investment to a showcase project. Regeneration would provide a high profile attraction to bolster the regional tourism and leisure product base. An experimental building would provide an opportunity to be innovative in not only design but also construction techniques, where fusion between designers and the construction industry could present alternatives to current building practices and where visitors and the community would be engaged with the project. The environmentally friendly' experimental building was designed 10 embrace energy efficiency, ecological waste treatment and provide a centre for envir nmental pducation, with facilities in skills training for the local community. The Visitor Attractions 145 anagement and marketing of a multi-faceted project requires a full understanding of site development and site management, with market segment behaviour and pricing strategies for the management of revenue being effectively implemented. The EcoTech Centre would form part of an economic growth pole (Higgins, 1983) where a group of propulsive enterprises' would produce widespread effects within the region. D'Hauteserre (1997) highlighted the positive economic impacts this technique brought to the Marne Valley since the establishment of Disneyland, Paris. The EcoTech Centre was planned by the partnership between Breckland District Council and the EcoTech Centre Trustees to be a high profile EU funded capital project to optimize benefits to the community. Offering an eco-based experience would attract additional investment into the region and alter the public perception of the attractions sector profile. Provision of a sustainable resource was seen as critical to the project. As part of e site development programme, a wind turbine with viewing platform was built by Ecotricity and opened to visitors in May 1999. This massive structure instantly pro- ded a focal point and Unique Selling Point (USP) for the site since there were no similar attractions in the UK. The decision to construct a viewing platform had been based upon visitor experiences of a similar attraction in Europe. The opening of the wind turbine has pushed visitor numbers up to 28,500 despite a revised target of 32,000 ich reflects current performance more accurately. It was recognized within the first year of operation that further development plans could not be indefinitely postponed and were critical to the attraction reaching its critical mass to ensure a sustainable and viable future. Ongoing projects to secure funding for the development of an experimental eco-house and an environmental management/energy advice centre remain core to the attraction's development. Through the use of COPIS funding, the attraction is to build an interactive walk- through compostor to enhance the attraction's coverage of future techniques in sus- ainability of resources. Other developments have included rainwater recycling systems and the construction of a Viking round tower using traditional techniques which acts as a counterbalance and is in contrast to the high tech design and materials used elsewhere on the site. As EcoTech matures as an attraction and the novelty factor diminishes the need for revenue management will increase. The reliance upon programmes of exhi- sitions, and improving the aids to interpreting exhibits, will form only part of the revenue management strategy and the shift towards more specialist and community- based micro-markets will need to be addressed (Johns and Hoseason, 2001). THE ECONOMICS OF VISITOR ATTRACTIONS The visitor attractions sector is highly fragmented and diverse (Bull, 1995). The very diversity of the market dictates the economic conditions which impact upon the market and the operators or suppliers within it. At one end of the product continuum, natural heritage sites are often free to visitors and managed either by government agencies, for example English Heritage or organizations like the National Trust that has charity status. At the other end of the continuum, there are commercially based organizations providing built attractions that require profit or revenue maximization (Bull, 1995; Tribe, 1995; Yeoman and Leask, 1999). Since alteration to public funding in the 1990s, many organizations, irrespective of organizational structure and status, have increas- ingly used commercial, i.e. revenue maximization, techniques to support an attraction's viability. Similar to the accommodation sector, visitor attractions (Yeoman and Leask, 146 Revenue Management and Pricing 1999) are capital intensive or are high in capital value, as in the case of built heritage sites. However, there is also an unpriced' value (Bull, 1995) within the economic structure of attractions. These include social cost/benefit pricing and tourist values that are elements included within the tourist product. They may be inseparable from the experience, but cannot be given a market value (Sinden and Worrell, 1979) and this particularly applies to the natural environment. Managers of visitor attractions sub- sequently manage revenue through profit maximization, break-even pricing or social cost/benefit pricing. As Bull (1995) points out, it makes comparison of economic or financial performance almost impossible, particularly where the local authority assists by providing financial support, or donations are made. A number of high profile projects funded through the National Lottery, for example the Millennium Dome or the Armouries in Sheffield, have foundered where altruism and social cost/benefit pricing has tried to defy gravity models along with economic modelling in demand and supply. The result is a distorted picture in terms of visitor numbers and ultimately the financial viability. A massive influx in major projects funded by the National Lottery has caused management problems for a number of existing attractions on national, regional and local scales. Wanhill (1998) identified attractions having high fixed costs either through the capital investment required to establish or to expand the development of an attraction. Operational and variable costs are impacted upon by the seasonality of the attraction and may force operators to use cost-orientated pricing to ensure contribution margins are met. While admissions prices form the core of income generation (Swarbrooke, 1999), each attraction suffers from an element of price discretion to cover short run operational costs (Bull, 1995; Wanhill, 1998). Low marginal costs may enable a greater range in price discretion. However, pricing strategies often include an element of the visitor's perception of value for money'. Hendon (1982) identified the heritage sector as being highly segmented and relatively inelastic, where changes in admission prices caused little negative impact upon revenue. Reliance on measuring admission prices based upon a general rule of market knowledge and visitor perception increases risks (Rogers, 1995). High visitor numbers are usually required to meet break-even points and this makes attractions susceptible to the vagaries of weather, which effect visitor numbers and the ability to effectively manage revenue. Yeoman and Leask (1999) demonstrated that heritage based attractions exhibit operational and financial seasonal dependency characteristics that increases the need for stronger evenue management to maximize revenue during peak periods. Swar- brooke (1999) suggested success must not be measured by visitor volume, but through visitor spend. Pricing strategies may target market segments and be used effectively to discriminate against visitors as a technique in visitor management particularly where a heritage attraction has reached its carrying capacity. Research by Prentice et al. (1998) indicates there should be a shift away from viewing visitors purely upon socio-economic profiling and move towards a model of benefit segmentation, as it may be a truer reflection of consumer behaviour and willingness to pay. Targeting 'baby-boomers', whose experience and preferences as consumers are different from those of previous generations, make marketing of attractions such as EcoTech for older age groups more challenging and breaks stereotype moulds of the 'over 55s' market, thus providing even greater opportunity for application of revenue management techniques (Johns and Hoseason, 2001). Visitor Attractions 147 MARKETING AND IDEAL MARKETS It has now been firmly established that tourist products are offered to highly segmented consumer markets either through behavioural (Cohen, 1979; Plog, 1973) or archetypal characteristics (Holloway and Robinson, 1995). Middleton (1996) suggested that cul- turally there was uniformity in drawing on a basic range of segments to visitor attractions irrespective of destination. These segments are broken down into: 1. Local residents living within half an hour's drive. 2. Regional residents making day visits and travelling up to two hours depending upon the motivating power of the site. 3. Visitors staying with friends and family within about an hour from the site. 4. Visitors staying in serviced or non-serviced accommodation within about an hour. 5. Group travel 6. School and educational visits. Prentice et al. (1998) recognized the importance of benefit segmentation rather than follow a too generalized socio-economic analysis and ignored the geographic nature of 'ideal markets', which Middleton indicated were important. Getz (1993) modelled the , 'tourist business district' in terms of attractions being mutually surrounded and inter- acting with tourism services (i.e., accommodation and transport) and the central functions of government, the retail sector, offices and meetings, where the access and movement of people were important. However, this does not fully explain the 'ideal market'. Attractions display spatial characteristics that cannot be simply analysed through distance decay models (Bull, 1995), consumer profiles or destination branding' of image or consumer lifestyle preference (Morgan and Pritchard, 2002). Distance decay assumes the level of activity decreases with distance measured either in time or absolute measurement and therefore enables a geographic market to be delineated. For spatial interaction to take place, there needs to be perfect complementarity, i.e., demand in one place has to be matched with supply in another (Ullman, 1956), and other stimulators such as fashionability and positioning of the destination as a brand (de Chernatony, 1993; Kotler et al., 1999). By using gravity models, marketers of visitor attractions should consider not only market segmentation processes, but also consider the attractions mass' as a pulling power. Where an intervening opportunity exists (i.e., alternative supply), an alternative attraction would only be visited by tourists if there were a criteria match. Empirical evidence suggests marketing managers tend to mis- match the degree of competition with other attractions without analyzing their own customer base to check behavioural characteristics. In terms of pricing strategies, there may be greater emphasis upon consumer perception in value for money' and the tourist values than maximization in revenue opportunities through value added processes. Christaller (1966) modelled location in terms of service hierarchy and matched these to distance and sizes of population to produce theoretical ideal markets. In reality, ideal markets' or catchment area, will produce not a rigid circle or hexagon on a map, but fluid lines based upon the attraction's mass' and the efficiency of flows within transport systems and networks. The key to recent growth in many attractions has been matching product develop- ment with demographic and lifestyle changes (Fry, 1997). Numerous attractions mirror the experience of the hospitality sector by implementing pricing structures to attract the over 55s (Ananth et al., 1992), particularly those with grandchildren. Changes in service 148 Revenue Management and Pricing provision has aimed at higher quality and more personalized service, e.g., membership schemes, timed tickets or restrictions in access to use retail or hospitality services. Attractions have increasingly recognized the importance of a growing secondary role in providing a meeting place where the emphasis is on hospitality or retail provision rather than a repeat visit to the core area of the attraction, whether it is an ecclesiastical site, museum, zoo or a themed site. REVENUE MANAGEMENT As the implementation of revenue management nears maturity as a management tool, published research now covers airlines (Larsen, 1988; Smith et al., 1992; Daudel and Vialle, 1994; Belobaba and Wilson, 1997; Ingold and Huyton, 1997), hotels (Orkin, 1988; Donaghy et al., 1995), tour operations (Hoseason and Johns, 1998; Laws, 1997), cruise (Hoseason, 2000) and car rental operations (Cross, 1998). These studies range from technology impact and implementation studies to marketing, human resource management, revenue and inventory management. Few studies have been made on built visitor attractions, whether they are heritage based or theme parks. The built visitor attractions industry shares a number of common characteristics with other travel and tourism sectors. Both heritage and purpose built visitor attraction sites have capacity relatively constrained either through the carrying capacity of the site or through other factors, e.g., planning permission or car parking facilities. Demand is both seasonal and highly segmented (Cross, 1998; Wanhill, 1998; Yeoman and Leask, 1999). Supply may also be constrained through seasonality or, in the case of heritage visitor attractions, through conservation policies. Subsequently, the different nature of mana- ging organizations where they straddle the public/private and charity divide requires fundamentally different strategies for managing revenue even though they may emulate revenue techniques from the private sector. While public sector organizations have to give greater consideration to social cost, the use of revenue maximization techniques may have impact upon funding through central and local government budgetary control. However, shifts in government funding have placed greater dependence on public sector organizations to re-evaluate revenue management and become more empowered and independent in control, making the implementation of revenue management techniques even more appropriate in their strategies for revenue management. Research by Yeoman and Leask (1999) into heritage visitor attractions in Scotland indicated that visitor attractions match to a greater or lesser extent the core necessary conditions and ingredients identified by Kimes (1989) in order to implement revenue maximizing techniques. Unlike the accommodation sector, visitor attractions are dedicated more specifically to a particular tourist market (Bull, 1995). Clearly, this indicates a more customized approach to implementation where careful consideration to the site and local conditions must be made. Cross (1998) suggested that where markets are mature, over-supplied and showing signs of congestion, organizations need to refocus on micro-markets for the benefits of effective revenue management to take place and it is here that visitor attractions now need to concentrate. Schwartz (1998) suggests that the perishability of the product and the customer's willingness to pay are in fact the key elements in revenue management and not the necessary conditions and ingredients identified by Kimes and Cross. These were felt to be overstated and may be contributing factors but embody misconceptions and mis- understandings of price demand elasticity and consumer behaviour. Visitor Attractions 149 The Millennium Commission supported a 4 billion programme covering over 180 capital projects to celebrate the millennium. In the visitor attractions market, impact studies tended to focus on individual projects at the time of funding bids being made, rather than a more holistic approach. While these projects have upgraded and enabled greater diversity in choice, this type of product development may impact upon pricing strategies (Middleton, 1996; Edgar, 1997; Poon, 1993) in order for new sites to reach critical mass in visitor numbers. Established visitor attractions have altered pricing strategies to counter any destabilization and lowering of revenue due to lower visitor numbers. Market capacity should therefore be given far higher visibility and inclusion in revenue management strategies. REVENUE MANAGEMENT AT ECOTECH As a new attraction, both the management team and trustees had been aware of the need to reach critical mass for visitor numbers within the first year of operations. Competition within an established market would be fierce, and any launch campaigns would have to shift from media hype to delivery of an experience'. A key factor in the performance of any new attraction is being ready for the main tourism season. Although the EcoTech Centre opened in the spring of 1999, delays to building and site completion coupled with poor weather did not turn the opening into a recipe for a disaster but did impact upon visitor targets that were downscaled to 32,000 per annum. Core concepts of revenue management were established within the business plan and focused upon: (a) pricing strategies; (b) main market segments; (c) trends in micro-markets; (d) incentives for repeat business; (e) booking lead-time trends for specialist groups and schools. Pricing strategies were set well within the range of local attractions and were thought to be 'about right. Quite early, qualitative research indicated that the first wave of visitors were environmentalists or organizations associated with environmental issues who would turn out to be quite critical of the centre. These groups had a high socio- economic profile of A, B, C1/2, who found the centrepiece exhibition 'Doomsday reiterating environmental issues as a core theme, but not offering solutions. The interpretation boards would not be fully in place until July 1999 which meant that the full impact of exhibition material could not be appreciated. Also, without the con- struction of the eco-house and the setting up of the advice centres for energy and environmental waste management for businesses, the EcoTech Centre will not be able to fulfil this role and will remain susceptible to criticism. Operationally, the centre suffered from similar tourist behaviour patterns experi- enced by other attractions within the area. Themed attractions and heritage properties see falls in attendance when hot weather conditions exist and they compete head-on with the beach or zoos. The EcoTech Centre was perceived to be an indoor attraction best suited to colder weather, which has brought to the front the need for continued site development to counteract this factor. The centre's design incorporated a passive solar collection system. On hot days visitors and staff found the experimental building too 150 Revenue Management and Pricing efficient in heat retention and this has caused modification work to be carried out to improve temperature and ventilation. Ecotricity's agreement to build a wind turbine with a viewing platform provided the EcoTech Centre with an additional showcase exhibit and provided a much-needed value-added element to the visit. Due for completion in May 1999, delays in con- struction and granting of Health & Safety Executive approval forced re-evaluation of visitor targets and the management of revenue as the turbine finally opened during the month of August. Between April and October 28,500 visitors were attracted to Eco- Tech, a reduction of 36 per cent from estimates made in the feasibility study. Despite delays and coping with a 'learning curve', the number of visitors was comparable to other visitor centres within Norfolk and enabled the centre to become more established within the attractions sector. In 2000, pricing strategies (see Appendix 1 at the end of this case study) were altered and the principles of revenue management (Cross, 1997) were applied even though they were not directly recognized as such. The wind turbine was priced separately with main entrance prices significantly reduced in order to focus on revenue generation from family or single adults with children. Research indicated the over 55s with grand- children also formed a significant segment of visitors. Their usage of the site would differ from other visitors and the pricing strategy ensured this group's requirements were being met. With a full programme of activities and exhibitions planned for the year, the wind turbine now provided the Unique Selling Point. New marketing and pricing strategies could now provide a more dynamic management plan with the shift in focus to micro-market segments. With a broadened base, the attraction could now effectively use pricing strategies based upon clear segmentation processes to allow sufficient price discrimination to improve revenue. A bold decision was made to close the centre on Saturdays during the off-peak period. Market-day in Swaffham and 'change-over day' for the regions' holiday homes and boats on the Norfolk Broads produced very low visitor numbers. In conjunction with new pricing strategies, a more defined marketing strategy towards a more formalized programme of educational visits for staff and school children was put together with a target of 6,000 visitors per annum. The impact of the new strategy saw a significant shift in relationships within revenue centres. Figure 13.1 shows there are clear indications that the new pricing strategy saw a significant improvement in secondary spend, which almost doubled the on-site spend. By implementing micro-marketing and pricing strategies, the enhanced on-site spend will begin to compensate for lower visitor numbers through improvement in visitor spend and value. As the attraction became established, the year-on-year spend made a major contribution to the attraction's revenue. Since the opening of EcoTech, an emergent pattern between seasonal visitor arrivals and the shop revenue ratios has become established. During peak periods of visitor arrivals, the value of secondary spend falls but remains a relatively stable constant ratio, whereas during the out of season period, the value of visitor spend is almost four times the main season's average. While this phenomena may be part explained by gift shopping and school holiday activities, it is also possible that poorer weather encourages a longer than planned visit to an indoor attraction as a 'change of scene'. Since gross profit margins are typically between 40 to 60 per cent, this revenue centre is making an active contribution to overall revenue management and smoothes the sea- sonality effect upon income fluctuations. Visitor Attractions 151 Shop sales -y-admissions % ratio 3 2.5 2 % 1.5 1999 - 2000 2000 - 2001 2001 - - 2002 1 0.5 0 April June Month August October December February Figure 13.1 New pricing strategy: impact of secondary spend REVENUE MANAGEMENT CONSTRAINTS The East of England Tourist Board (2000) estimated there were 4.18 million trips to Norfolk in 1998, and visitors spent 603 million on tourism related services; 4.5 per cent were overseas visitors who spent 54.5 million. In 1998 Norfolk had around half a million visits spread across 69 major visitor attractions (EETB, 2000, and see Figure 13.2). Recent trends indicate many attractions within the region have either remained stable or seen a reduction of between 3 and 7.5 per cent, depending upon year and the type of attraction. These figures broadly follow known national trends (Hanna, 1999; Howell, 2000). Many attractions within the region have a core geographic market representing up to 40 per cent of the visitors, which demonstrates that proximity to major towns influences visitor behaviour and should be factored into marketing and revenue strategies. Consideration must also be given to a number of constraints that impact upon the EcoTech Centre and similar attractions in Norfolk. Empirical evidence suggests that the following factors need to be included within the revenue management system: 1. Timing or planning of visits 2. The size of the ideal market and its capacity 3. Seasonality. Day-trippers do not pre-plan trips in the same way as other tourists use cognitive decision making models (Chen, 1997; Prideaux and Kininmont, 1999). Recent research from different locations within Norfolk indicate that between 20 to 30 per cent decided 152 Revenue Management and Pricing Market share of Norfolk visitor attractions 1998 8% Historic houses and monuments 10% Cathedrals 34% Misc. attractions -4% Gardens 14% Museums and galleries 11% Wildlife attractions 2% Work places 5% Visitor centres 5% Steam railways 4% Leisure parks and 1% Country parks -2% Farms piers Figure 13.2 Market share of Norfolk visitor attractions 1998, per cent (Source: East of England Tourist Board (2000)) to visit an attraction on the spur of the moment' and between 16 to 35 per cent on the day of visit. Between 15 and 21 per cent would make a decision two days prior to the visit and between 8 and 25 per cent would plan a visit up to a week before. Less than 23 per cent would make trip plans more than a week ahead. While weather is a significant element in the planning process, responses across all segments indicated the decision- making process was subject to an emotional response within the decision group. No amount of advertising or promotions can fully exploit variance and change influences within these groups. The second constraint is the concept of the 'ideal market and threshold population sizes needed to support services (Christaller, 1966). Norfolk has a population of 772,000 and a density of 144 people per square kilometre where 80 per cent of land use is agriculture. In economic location modelling there is insufficient local population to support any of the major attractions within the county and therefore relies heavily upon the 4 million visitors to compensate and enable attractions to reach threshold figures. Visitor Attractions 153 While many major Lottery projects have been located within major urban areas within the UK, any expansion in capacity or shortfall in visitor numbers leaves all attractions exposed to a lowering of revenue performance. Clearly, the development plans for the EcoTech Centre will broaden its base as an attraction, but as the capacity within the visitor attractions market increases, the exposure to lower performance remains. This constriction in opportunity for revenue management needs careful consideration prior to reshaping marketing strategies. Empirical evidence also indicates that visitor attractions may be an anomaly within gravity models devised by Ullman (1956). Gravity modelling assumes the larger the function of place or level in service, human behaviour would follow Reilly's Law, i.e., the larger the attraction, the larger the pull factor. Research indicates that local residents within 15 miles of an attraction may not visit it due to a combination of experience or poor perception of the attraction or by what constitutes a day out'. Between 20 and 42 per cent had not visited an attraction adjacent to where they resided and yet between 50 and 70 per cent would travel more than 20 miles to an attraction. Fewer than 15 per cent would travel less than 15 miles to an attraction and this creates a 'doughnut effect around an attraction. Clearly, visitors do not see a local attraction as a 'day out' and this has major implications in marketing (Kotler et al.. 1999) and in revenue management. To regain local resident/visitor confidence in the attraction, highly targeted marketing campaigns with additional concessions will be needed to improve revenue performance from this segment. Capacity management has been identified by Kimes (1989, 1997) and Cross (1997, 1998) as an essential element for revenue management to be effective. Should there be capacity increases within the region's visitor attractions, then revenue must be expected to fall, unless the volume of visitors into the region has increased, as thresholds may not have been reached. The third constraint is seasonality (Cross, 1998; Wanhill, 1998; Yeoman and Leask, 1999). EETB figures show that 35 per cent of visitors to Norfolk arrive in the period July to September. An additional 26 per cent visit between April to June. However, the statistics do not show that the peak in activity spans only a six to eight week period across July and August, when operational efficiency is at its peak. Yeoman and Leask (1999) suggested seasonality increased the need for revenue maximizing techniques to be implemented to offset low season performance. The implementation of a programme for educational visits and specialist activities, particularly during half term and school holidays, has eased seasonal variance. Revenue figures show these activities have boosted out of seasonal revenue and attracted higher secondary spend (Figure 13.1). CONCLUSIONS Revenue management is designed to optimize revenue. Institutional change and less reliance upon public sector or European Union funding will force a greater need for effective revenue management. The EcoTech Centre is severely constrained by the economic thresholds that operate within the ideal market locally. There is insufficient population to support the region's attractions without the seasonal influx of visitors. The 'doughnut effect which surrounds the attractions has major implications towards revenue management. Marketing and revenue management strategies need to refocus their attention on this segment as local residents within 15 miles of an attraction form the threshold for survival. Add an element of seasonality together with performance in weather and all of the attractions then become very exposed to marginalized revenue 154 Revenue Management and Pricing performance. Too little attention has been paid at national and regional level in terms of the changes in capacity through Lottery funded projects. The impact is not segment selective and can hit the educational sector as sharply as any other. As the EcoTech Centre matures as a visitor attraction, the plans to build an experimental house together with the business advice centre will become critical to the long-term success of the centre. The behaviour of the micro-market segments is the essence of successful revenue management implementation. Without a continued programme of innovative exhibi- tions and site development, the EcoTech Centre will fail one of its original objectives, that of experimentation and innovation. DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. Identify and describe factors which might act as constraints upon revenue man- agement at an attraction. 2. Define capacity management and propose what strategies could be adopted to improve revenue management. 3. Analyse market segmentation of attractions and devise a strategy for improving revenue from one major and one niche segment. 13 Revenue Management in Visitor Attractions: A Case Study of the EcoTech Centre, Swaffham, Norfolk Julian Hoseason INTRODUCTION Visitor attractions form an integral part of the total tourism product for both the domestic and incoming visitors to a region. Attractions cover a broad spectrum of activities based upon the natural or man-made environment ranging from heritage sites through to purpose built centres usually devoted to leisure and recreational activities (Getz, 1993; Swarbrooke, 1999; Hall and Page, 1999). The attractions sector is complex in definition and provides different levels of engagement with the visitor when the encounter takes place (Crouch, 1999). While visitors enjoy this variety, attractions offer an intangible experience (Yeoman and Leask, 1999), which makes visitor man- agement and marketing complex (Prentice et al., 1998) since seasonality and a spatial element enter into the pricing strategy. In the mid-1990s Norfolk was experiencing a decline in its agricultural base and indicators suggested alternative strategies needed implementation to avoid unemploy- ment and social blight in the community of Swaffham. Regional funding from the European Union enabled an imaginative proposal for the development of a sustainable attraction to act as a growth-pole for inward investment. The EcoTech Centre was to be an experimental showcase in design and construction techniques with the emphasis upon environmental management and education. As an attraction, the EcoTech Centre would need to reach a critical mass of around 50,000 visitors per annum to be viable. The centre would be competing against the region's existing attractions, the coast and an area of wetland known as the 'Norfolk Broads'. As the implementation of revenue management matures across the travel and tourism industry, the resultant benefits must make the implementation or adoption a basic management strategy. Research indicates that the attractions sector has yet to Revenue Management and Pricing 144 extensively adopt revenue management as a management technique, therefore this sector produces lower financial performance figures compared to other sectors. Research by Yeoman and Leask (1999) into heritage visitor attractions indicated thar the highly seasonal nature of the market necessitated revenue management techniques being applied to main season activities with more specialist activities being introduced during low or out of season periods for maximization of revenue. However, major capital projects funded by the UK's National Lottery, may have caused distortion to the attractions sector at local, regional and national level where sudden increases in market capacity cannot be met by corresponding increases in visitor activity. Over 1.2 billion has been awarded to over 180 major projects with an additional 2.8 billioa being awarded through European funded grants for projects (Anon, 2000). Key pro- jects like the Royal Armouries in Leeds, and the Earth Centre, failed to live up te projections not only of visitor numbers but also in revenue management where over- estimates and losses threatened their future (McClarence, 2000). For the EcoTech Centre, its future success may not simply lie in developing a highly innovative attrac- tion, but consideration of micro-market behaviour in relation to the capacity of the 'ideal market or catchment area characteristics. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES The aim of this case study is to demonstrate how simple revenue management tech- niques encourage visitors spend in higher profit earning centres within an attraction The objectives are to: 1. Evaluate the impact of a high profile attraction in the attractions market. 2. Evaluate the relationship between pricing and revenue strategies. 3. Analyze the relationship between attractions design and critical mass in attracting visitor numbers. BACKGROUND The Eco Tech Centre has been built on a brownfield site on the edge of Swaffham, a market town in the centre of Norfolk. Sited on a former derelict firework factory, the project aimed at cleaning up a polluted site for the benefit of the community. The original proposal envisaged an experimental building in terms of design and com struction techniques, attracting 50,000 visitors annually, and providing an interactive learning centre based on environmental education. By targeting the enhancement of leisure and tourism facilities it was hoped to attract high inward investment to a showcase project. Regeneration would provide a high profile attraction to bolster the regional tourism and leisure product base. An experimental building would provide an opportunity to be innovative in not only design but also construction techniques, where fusion between designers and the construction industry could present alternatives to current building practices and where visitors and the community would be engaged with the project. The environmentally friendly' experimental building was designed 10 embrace energy efficiency, ecological waste treatment and provide a centre for envir nmental pducation, with facilities in skills training for the local community. The Visitor Attractions 145 anagement and marketing of a multi-faceted project requires a full understanding of site development and site management, with market segment behaviour and pricing strategies for the management of revenue being effectively implemented. The EcoTech Centre would form part of an economic growth pole (Higgins, 1983) where a group of propulsive enterprises' would produce widespread effects within the region. D'Hauteserre (1997) highlighted the positive economic impacts this technique brought to the Marne Valley since the establishment of Disneyland, Paris. The EcoTech Centre was planned by the partnership between Breckland District Council and the EcoTech Centre Trustees to be a high profile EU funded capital project to optimize benefits to the community. Offering an eco-based experience would attract additional investment into the region and alter the public perception of the attractions sector profile. Provision of a sustainable resource was seen as critical to the project. As part of e site development programme, a wind turbine with viewing platform was built by Ecotricity and opened to visitors in May 1999. This massive structure instantly pro- ded a focal point and Unique Selling Point (USP) for the site since there were no similar attractions in the UK. The decision to construct a viewing platform had been based upon visitor experiences of a similar attraction in Europe. The opening of the wind turbine has pushed visitor numbers up to 28,500 despite a revised target of 32,000 ich reflects current performance more accurately. It was recognized within the first year of operation that further development plans could not be indefinitely postponed and were critical to the attraction reaching its critical mass to ensure a sustainable and viable future. Ongoing projects to secure funding for the development of an experimental eco-house and an environmental management/energy advice centre remain core to the attraction's development. Through the use of COPIS funding, the attraction is to build an interactive walk- through compostor to enhance the attraction's coverage of future techniques in sus- ainability of resources. Other developments have included rainwater recycling systems and the construction of a Viking round tower using traditional techniques which acts as a counterbalance and is in contrast to the high tech design and materials used elsewhere on the site. As EcoTech matures as an attraction and the novelty factor diminishes the need for revenue management will increase. The reliance upon programmes of exhi- sitions, and improving the aids to interpreting exhibits, will form only part of the revenue management strategy and the shift towards more specialist and community- based micro-markets will need to be addressed (Johns and Hoseason, 2001). THE ECONOMICS OF VISITOR ATTRACTIONS The visitor attractions sector is highly fragmented and diverse (Bull, 1995). The very diversity of the market dictates the economic conditions which impact upon the market and the operators or suppliers within it. At one end of the product continuum, natural heritage sites are often free to visitors and managed either by government agencies, for example English Heritage or organizations like the National Trust that has charity status. At the other end of the continuum, there are commercially based organizations providing built attractions that require profit or revenue maximization (Bull, 1995; Tribe, 1995; Yeoman and Leask, 1999). Since alteration to public funding in the 1990s, many organizations, irrespective of organizational structure and status, have increas- ingly used commercial, i.e. revenue maximization, techniques to support an attraction's viability. Similar to the accommodation sector, visitor attractions (Yeoman and Leask, 146 Revenue Management and Pricing 1999) are capital intensive or are high in capital value, as in the case of built heritage sites. However, there is also an unpriced' value (Bull, 1995) within the economic structure of attractions. These include social cost/benefit pricing and tourist values that are elements included within the tourist product. They may be inseparable from the experience, but cannot be given a market value (Sinden and Worrell, 1979) and this particularly applies to the natural environment. Managers of visitor attractions sub- sequently manage revenue through profit maximization, break-even pricing or social cost/benefit pricing. As Bull (1995) points out, it makes comparison of economic or financial performance almost impossible, particularly where the local authority assists by providing financial support, or donations are made. A number of high profile projects funded through the National Lottery, for example the Millennium Dome or the Armouries in Sheffield, have foundered where altruism and social cost/benefit pricing has tried to defy gravity models along with economic modelling in demand and supply. The result is a distorted picture in terms of visitor numbers and ultimately the financial viability. A massive influx in major projects funded by the National Lottery has caused management problems for a number of existing attractions on national, regional and local scales. Wanhill (1998) identified attractions having high fixed costs either through the capital investment required to establish or to expand the development of an attraction. Operational and variable costs are impacted upon by the seasonality of the attraction and may force operators to use cost-orientated pricing to ensure contribution margins are met. While admissions prices form the core of income generation (Swarbrooke, 1999), each attraction suffers from an element of price discretion to cover short run operational costs (Bull, 1995; Wanhill, 1998). Low marginal costs may enable a greater range in price discretion. However, pricing strategies often include an element of the visitor's perception of value for money'. Hendon (1982) identified the heritage sector as being highly segmented and relatively inelastic, where changes in admission prices caused little negative impact upon revenue. Reliance on measuring admission prices based upon a general rule of market knowledge and visitor perception increases risks (Rogers, 1995). High visitor numbers are usually required to meet break-even points and this makes attractions susceptible to the vagaries of weather, which effect visitor numbers and the ability to effectively manage revenue. Yeoman and Leask (1999) demonstrated that heritage based attractions exhibit operational and financial seasonal dependency characteristics that increases the need for stronger evenue management to maximize revenue during peak periods. Swar- brooke (1999) suggested success must not be measured by visitor volume, but through visitor spend. Pricing strategies may target market segments and be used effectively to discriminate against visitors as a technique in visitor management particularly where a heritage attraction has reached its carrying capacity. Research by Prentice et al. (1998) indicates there should be a shift away from viewing visitors purely upon socio-economic profiling and move towards a model of benefit segmentation, as it may be a truer reflection of consumer behaviour and willingness to pay. Targeting 'baby-boomers', whose experience and preferences as consumers are different from those of previous generations, make marketing of attractions such as EcoTech for older age groups more challenging and breaks stereotype moulds of the 'over 55s' market, thus providing even greater opportunity for application of revenue management techniques (Johns and Hoseason, 2001). Visitor Attractions 147 MARKETING AND IDEAL MARKETS It has now been firmly established that tourist products are offered to highly segmented consumer markets either through behavioural (Cohen, 1979; Plog, 1973) or archetypal characteristics (Holloway and Robinson, 1995). Middleton (1996) suggested that cul- turally there was uniformity in drawing on a basic range of segments to visitor attractions irrespective of destination. These segments are broken down into: 1. Local residents living within half an hour's drive. 2. Regional residents making day visits and travelling up to two hours depending upon the motivating power of the site. 3. Visitors staying with friends and family within about an hour from the site. 4. Visitors staying in serviced or non-serviced accommodation within about an hour. 5. Group travel 6. School and educational visits. Prentice et al. (1998) recognized the importance of benefit segmentation rather than follow a too generalized socio-economic analysis and ignored the geographic nature of 'ideal markets', which Middleton indicated were important. Getz (1993) modelled the , 'tourist business district' in terms of attractions being mutually surrounded and inter- acting with tourism services (i.e., accommodation and transport) and the central functions of government, the retail sector, offices and meetings, where the access and movement of people were important. However, this does not fully explain the 'ideal market'. Attractions display spatial characteristics that cannot be simply analysed through distance decay models (Bull, 1995), consumer profiles or destination branding' of image or consumer lifestyle preference (Morgan and Pritchard, 2002). Distance decay assumes the level of activity decreases with distance measured either in time or absolute measurement and therefore enables a geographic market to be delineated. For spatial interaction to take place, there needs to be perfect complementarity, i.e., demand in one place has to be matched with supply in another (Ullman, 1956), and other stimulators such as fashionability and positioning of the destination as a brand (de Chernatony, 1993; Kotler et al., 1999). By using gravity models, marketers of visitor attractions should consider not only market segmentation processes, but also consider the attractions mass' as a pulling power. Where an intervening opportunity exists (i.e., alternative supply), an alternative attraction would only be visited by tourists if there were a criteria match. Empirical evidence suggests marketing managers tend to mis- match the degree of competition with other attractions without analyzing their own customer base to check behavioural characteristics. In terms of pricing strategies, there may be greater emphasis upon consumer perception in value for money' and the tourist values than maximization in revenue opportunities through value added processes. Christaller (1966) modelled location in terms of service hierarchy and matched these to distance and sizes of population to produce theoretical ideal markets. In reality, ideal markets' or catchment area, will produce not a rigid circle or hexagon on a map, but fluid lines based upon the attraction's mass' and the efficiency of flows within transport systems and networks. The key to recent growth in many attractions has been matching product develop- ment with demographic and lifestyle changes (Fry, 1997). Numerous attractions mirror the experience of the hospitality sector by implementing pricing structures to attract the over 55s (Ananth et al., 1992), particularly those with grandchildren. Changes in service 148 Revenue Management and Pricing provision has aimed at higher quality and more personalized service, e.g., membership schemes, timed tickets or restrictions in access to use retail or hospitality services. Attractions have increasingly recognized the importance of a growing secondary role in providing a meeting place where the emphasis is on hospitality or retail provision rather than a repeat visit to the core area of the attraction, whether it is an ecclesiastical site, museum, zoo or a themed site. REVENUE MANAGEMENT As the implementation of revenue management nears maturity as a management tool, published research now covers airlines (Larsen, 1988; Smith et al., 1992; Daudel and Vialle, 1994; Belobaba and Wilson, 1997; Ingold and Huyton, 1997), hotels (Orkin, 1988; Donaghy et al., 1995), tour operations (Hoseason and Johns, 1998; Laws, 1997), cruise (Hoseason, 2000) and car rental operations (Cross, 1998). These studies range from technology impact and implementation studies to marketing, human resource management, revenue and inventory management. Few studies have been made on built visitor attractions, whether they are heritage based or theme parks. The built visitor attractions industry shares a number of common characteristics with other travel and tourism sectors. Both heritage and purpose built visitor attraction sites have capacity relatively constrained either through the carrying capacity of the site or through other factors, e.g., planning permission or car parking facilities. Demand is both seasonal and highly segmented (Cross, 1998; Wanhill, 1998; Yeoman and Leask, 1999). Supply may also be constrained through seasonality or, in the case of heritage visitor attractions, through conservation policies. Subsequently, the different nature of mana- ging organizations where they straddle the public/private and charity divide requires fundamentally different strategies for managing revenue even though they may emulate revenue techniques from the private sector. While public sector organizations have to give greater consideration to social cost, the use of revenue maximization techniques may have impact upon funding through central and local government budgetary control. However, shifts in government funding have placed greater dependence on public sector organizations to re-evaluate revenue management and become more empowered and independent in control, making the implementation of revenue management techniques even more appropriate in their strategies for revenue management. Research by Yeoman and Leask (1999) into heritage visitor attractions in Scotland indicated that visitor attractions match to a greater or lesser extent the core necessary conditions and ingredients identified by Kimes (1989) in order to implement revenue maximizing techniques. Unlike the accommodation sector, visitor attractions are dedicated more specifically to a particular tourist market (Bull, 1995). Clearly, this indicates a more customized approach to implementation where careful consideration to the site and local conditions must be made. Cross (1998) suggested that where markets are mature, over-supplied and showing signs of congestion, organizations need to refocus on micro-markets for the benefits of effective revenue management to take place and it is here that visitor attractions now need to concentrate. Schwartz (1998) suggests that the perishability of the product and the customer's willingness to pay are in fact the key elements in revenue management and not the necessary conditions and ingredients identified by Kimes and Cross. These were felt to be overstated and may be contributing factors but embody misconceptions and mis- understandings of price demand elasticity and consumer behaviour. Visitor Attractions 149 The Millennium Commission supported a 4 billion programme covering over 180 capital projects to celebrate the millennium. In the visitor attractions market, impact studies tended to focus on individual projects at the time of funding bids being made, rather than a more holistic approach. While these projects have upgraded and enabled greater diversity in choice, this type of product development may impact upon pricing strategies (Middleton, 1996; Edgar, 1997; Poon, 1993) in order for new sites to reach critical mass in visitor numbers. Established visitor attractions have altered pricing strategies to counter any destabilization and lowering of revenue due to lower visitor numbers. Market capacity should therefore be given far higher visibility and inclusion in revenue management strategies. REVENUE MANAGEMENT AT ECOTECH As a new attraction, both the management team and trustees had been aware of the need to reach critical mass for visitor numbers within the first year of operations. Competition within an established market would be fierce, and any launch campaigns would have to shift from media hype to delivery of an experience'. A key factor in the performance of any new attraction is being ready for the main tourism season. Although the EcoTech Centre opened in the spring of 1999, delays to building and site completion coupled with poor weather did not turn the opening into a recipe for a disaster but did impact upon visitor targets that were downscaled to 32,000 per annum. Core concepts of revenue management were established within the business plan and focused upon: (a) pricing strategies; (b) main market segments; (c) trends in micro-markets; (d) incentives for repeat business; (e) booking lead-time trends for specialist groups and schools. Pricing strategies were set well within the range of local attractions and were thought to be 'about right. Quite early, qualitative research indicated that the first wave of visitors were environmentalists or organizations associated with environmental issues who would turn out to be quite critical of the centre. These groups had a high socio- economic profile of A, B, C1/2, who found the centrepiece exhibition 'Doomsday reiterating environmental issues as a core theme, but not offering solutions. The interpretation boards would not be fully in place until July 1999 which meant that the full impact of exhibition material could not be appreciated. Also, without the con- struction of the eco-house and the setting up of the advice centres for energy and environmental waste management for businesses, the EcoTech Centre will not be able to fulfil this role and will remain susceptible to criticism. Operationally, the centre suffered from similar tourist behaviour patterns experi- enced by other attractions within the area. Themed attractions and heritage properties see falls in attendance when hot weather conditions exist and they compete head-on with the beach or zoos. The EcoTech Centre was perceived to be an indoor attraction best suited to colder weather, which has brought to the front the need for continued site development to counteract this factor. The centre's design incorporated a passive solar collection system. On hot days visitors and staff found the experimental building too 150 Revenue Management and Pricing efficient in heat retention and this has caused modification work to be carried out to improve temperature and ventilation. Ecotricity's agreement to build a wind turbine with a viewing platform provided the EcoTech Centre with an additional showcase exhibit and provided a much-needed value-added element to the visit. Due for completion in May 1999, delays in con- struction and granting of Health & Safety Executive approval forced re-evaluation of visitor targets and the management of revenue as the turbine finally opened during the month of August. Between April and October 28,500 visitors were attracted to Eco- Tech, a reduction of 36 per cent from estimates made in the feasibility study. Despite delays and coping with a 'learning curve', the number of visitors was comparable to other visitor centres within Norfolk and enabled the centre to become more established within the attractions sector. In 2000, pricing strategies (see Appendix 1 at the end of this case study) were altered and the principles of revenue management (Cross, 1997) were applied even though they were not directly recognized as such. The wind turbine was priced separately with main entrance prices significantly reduced in order to focus on revenue generation from family or single adults with children. Research indicated the over 55s with grand- children also formed a significant segment of visitors. Their usage of the site would differ from other visitors and the pricing strategy ensured this group's requirements were being met. With a full programme of activities and exhibitions planned for the year, the wind turbine now provided the Unique Selling Point. New marketing and pricing strategies could now provide a more dynamic management plan with the shift in focus to micro-market segments. With a broadened base, the attraction could now effectively use pricing strategies based upon clear segmentation processes to allow sufficient price discrimination to improve revenue. A bold decision was made to close the centre on Saturdays during the off-peak period. Market-day in Swaffham and 'change-over day' for the regions' holiday homes and boats on the Norfolk Broads produced very low visitor numbers. In conjunction with new pricing strategies, a more defined marketing strategy towards a more formalized programme of educational visits for staff and school children was put together with a target of 6,000 visitors per annum. The impact of the new strategy saw a significant shift in relationships within revenue centres. Figure 13.1 shows there are clear indications that the new pricing strategy saw a significant improvement in secondary spend, which almost doubled the on-site spend. By implementing micro-marketing and pricing strategies, the enhanced on-site spend will begin to compensate for lower visitor numbers through improvement in visitor spend and value. As the attraction became established, the year-on-year spend made a major contribution to the attraction's revenue. Since the opening of EcoTech, an emergent pattern between seasonal visitor arrivals and the shop revenue ratios has become established. During peak periods of visitor arrivals, the value of secondary spend falls but remains a relatively stable constant ratio, whereas during the out of season period, the value of visitor spend is almost four times the main season's average. While this phenomena may be part explained by gift shopping and school holiday activities, it is also possible that poorer weather encourages a longer than planned visit to an indoor attraction as a 'change of scene'. Since gross profit margins are typically between 40 to 60 per cent, this revenue centre is making an active contribution to overall revenue management and smoothes the sea- sonality effect upon income fluctuations. Visitor Attractions 151 Shop sales -y-admissions % ratio 3 2.5 2 % 1.5 1999 - 2000 2000 - 2001 2001 - - 2002 1 0.5 0 April June Month August October December February Figure 13.1 New pricing strategy: impact of secondary spend REVENUE MANAGEMENT CONSTRAINTS The East of England Tourist Board (2000) estimated there were 4.18 million trips to Norfolk in 1998, and visitors spent 603 million on tourism related services; 4.5 per cent were overseas visitors who spent 54.5 million. In 1998 Norfolk had around half a million visits spread across 69 majorStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

100% Satisfaction Guaranteed-or Get a Refund!

Step: 2Unlock detailed examples and clear explanations to master concepts

Step: 3Unlock to practice, ask and learn with real-world examples

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

-

Access 30 Million+ textbook solutions.

Access 30 Million+ textbook solutions.

-

Ask unlimited questions from AI Tutors.

Ask unlimited questions from AI Tutors.

-

Order free textbooks.

Order free textbooks.

-

100% Satisfaction Guaranteed-or Get a Refund!

100% Satisfaction Guaranteed-or Get a Refund!

Claim Your Hoodie Now!

Study Smart with AI Flashcards

Access a vast library of flashcards, create your own, and experience a game-changing transformation in how you learn and retain knowledge

Explore Flashcards