Question: please conduct a comprehensive analysis for the case and briefly explain those question; 1, How would you define Whole Foods industry? 2, How would you

please conduct a comprehensive analysis for the case and briefly explain those question;

1, How would you define Whole Foods industry?

2, How would you describe Whole Foods strategy? And how attractive is Whole Foods

current market position?

please explain briefly; thanks

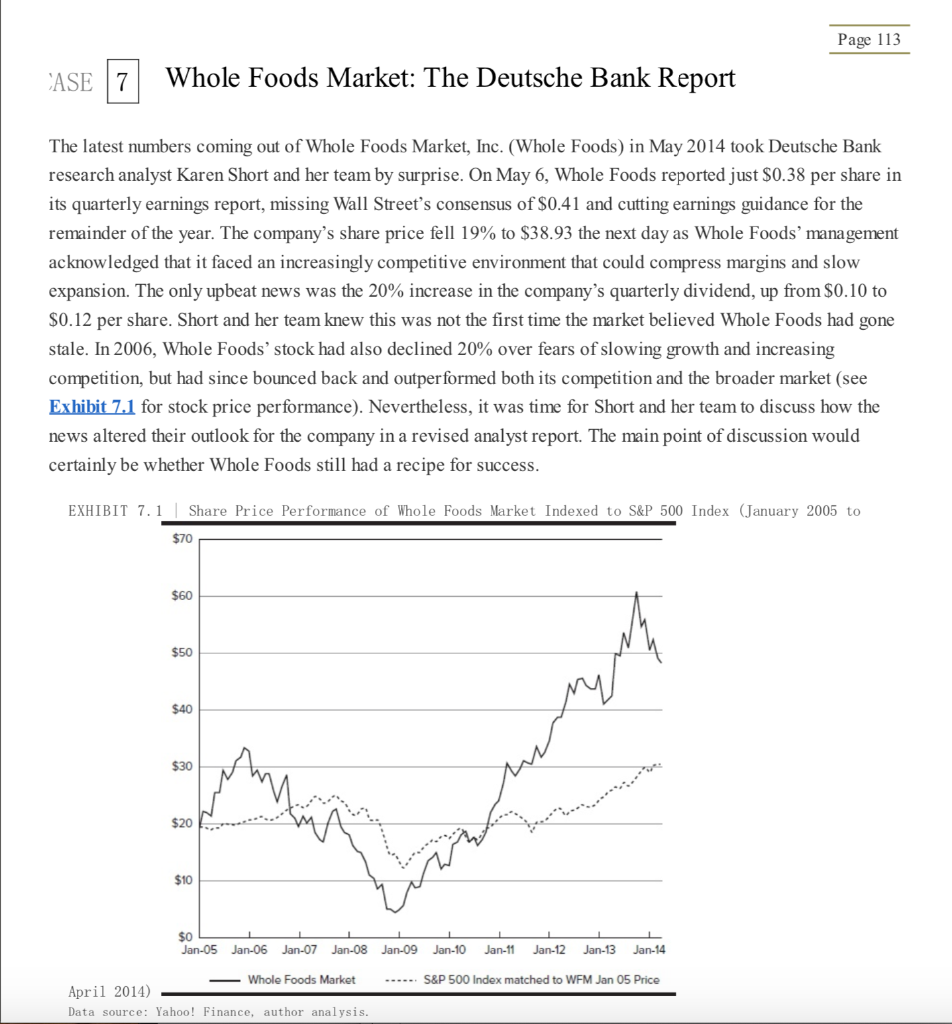

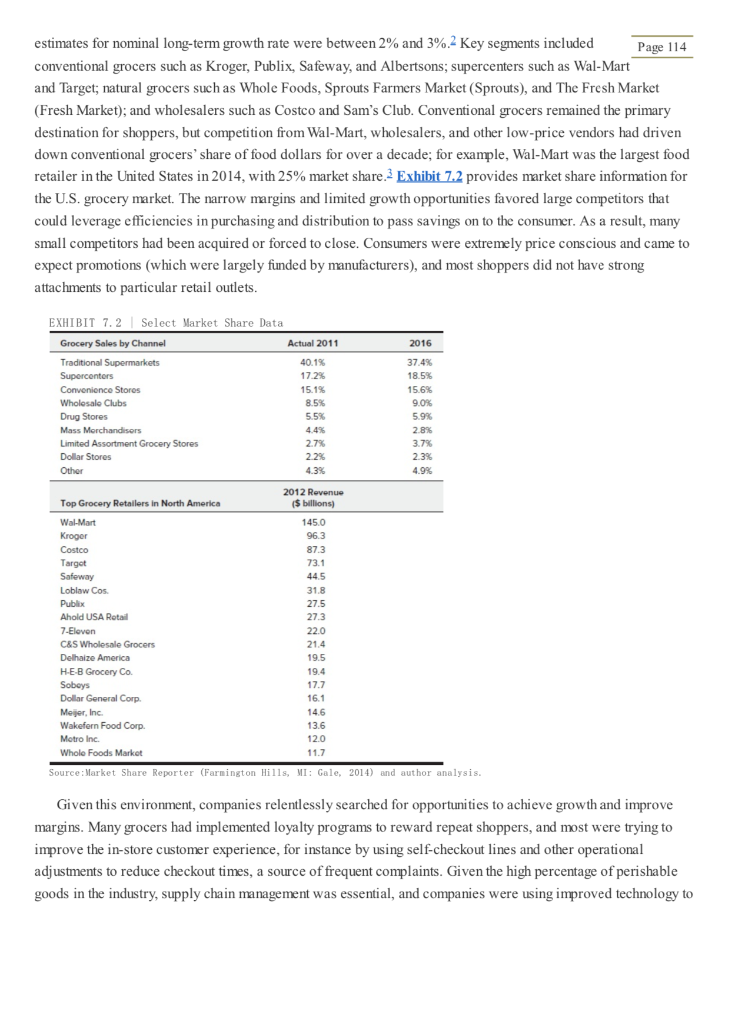

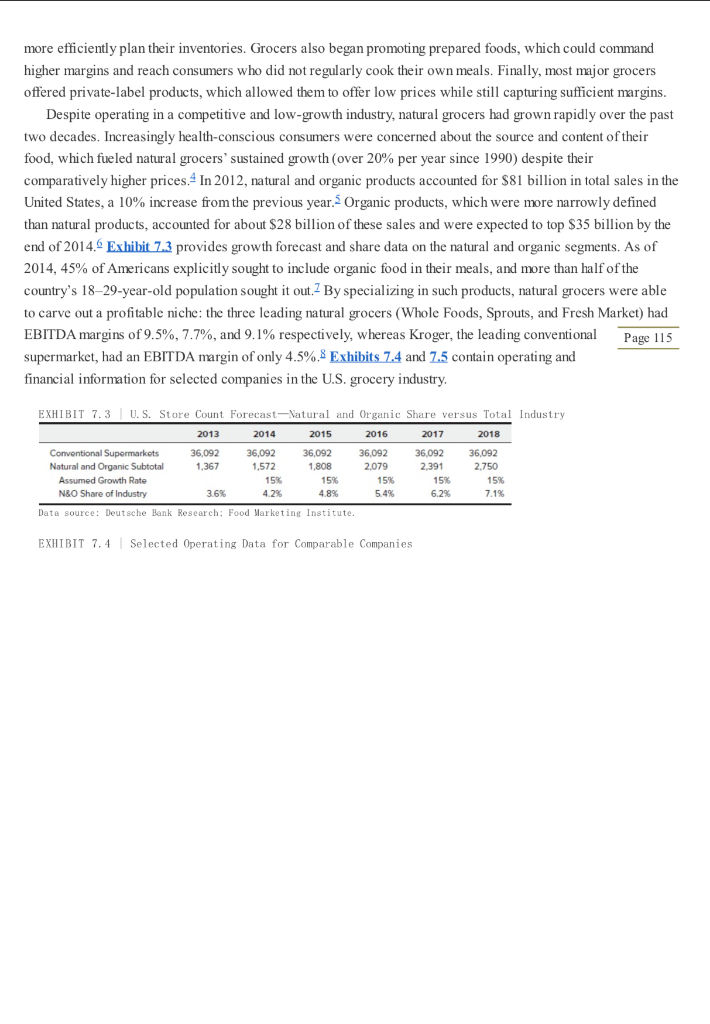

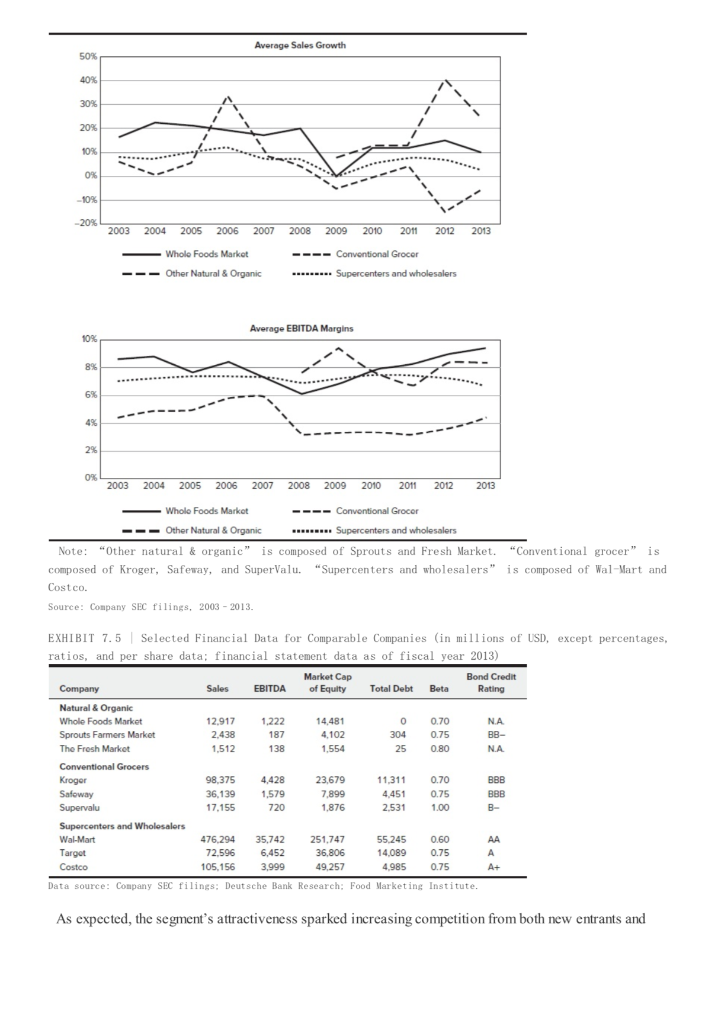

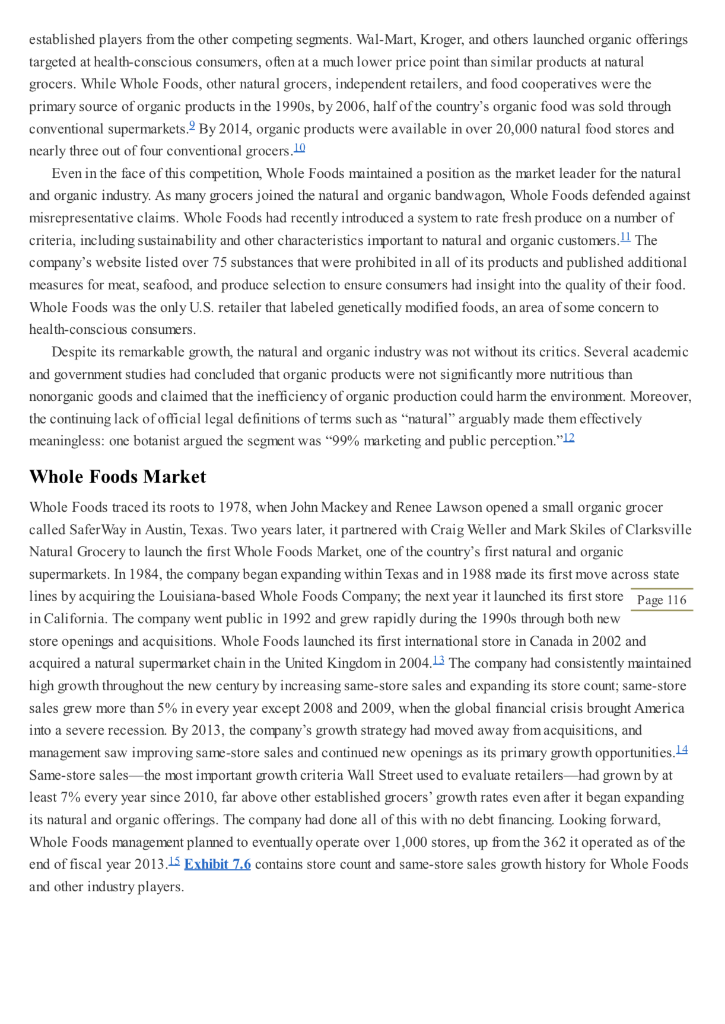

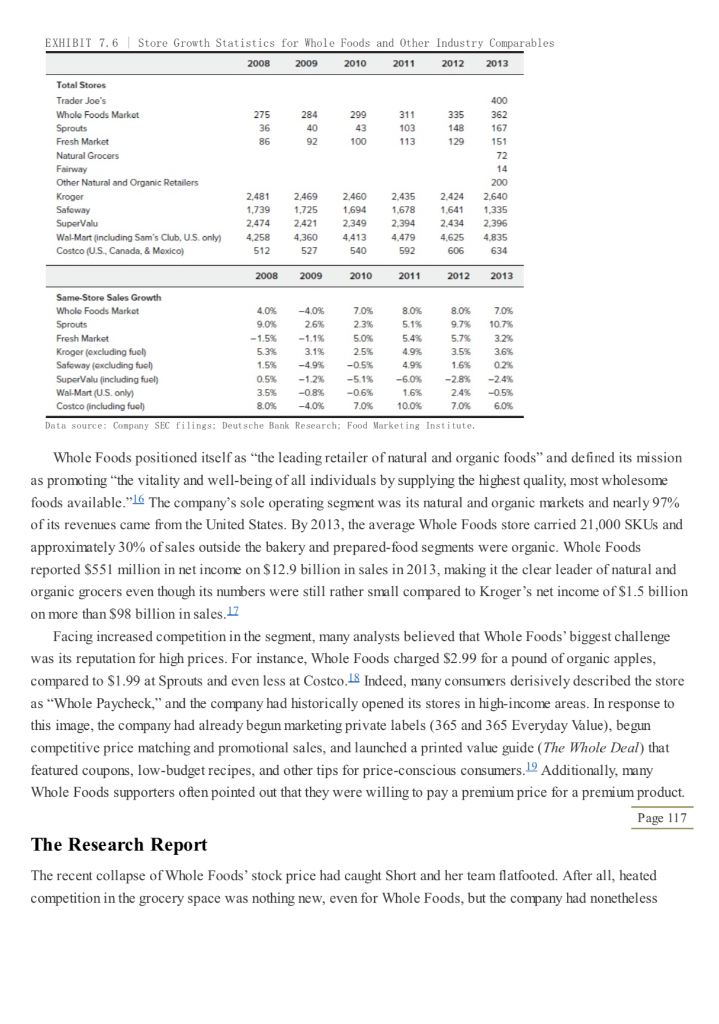

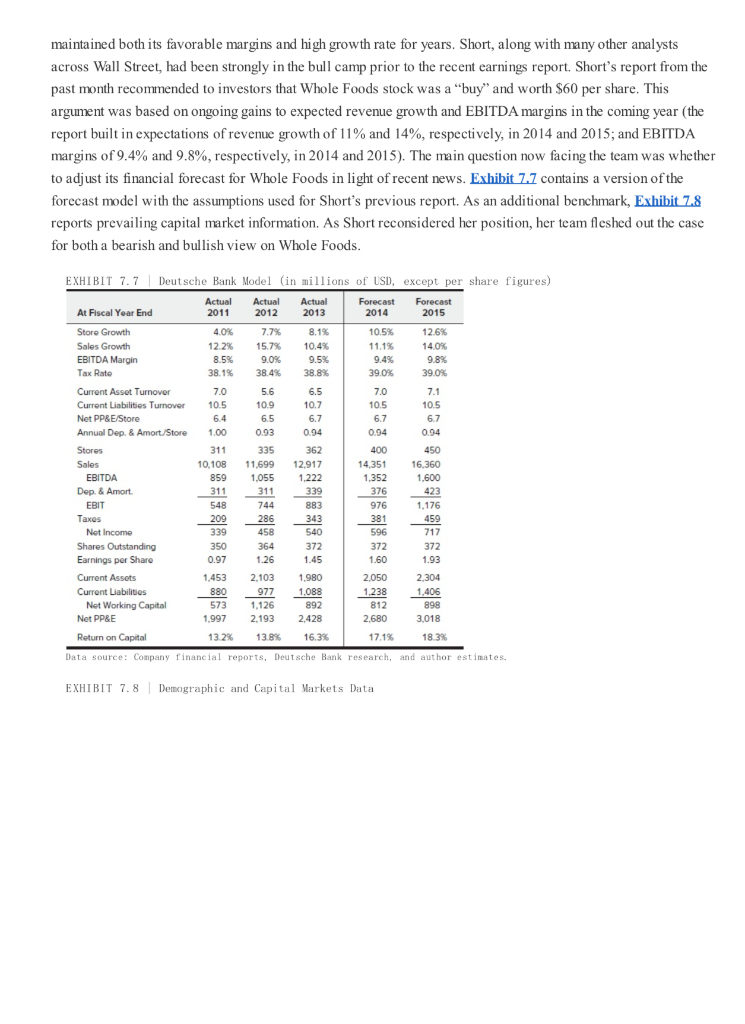

Page 113 CASE 7 Whole Foods Market: The Deutsche Bank Report The latest numbers coming out of Whole Foods Market, Inc. (Whole Foods) in May 2014 took Deutsche Bank research analyst Karen Short and her team by surprise. On May 6, Whole Foods reported just $0.38 per share in its quarterly earnings report, missing Wall Street's consensus of $0.41 and cutting earnings guidance for the remainder of the year. The company's share price fell 19% to $38.93 the next day as Whole Foods' management acknowledged that it faced an increasingly competitive environment that could compress margins and slow expansion. The only upbeat news was the 20% increase in the company's quarterly dividend, up from $0.10 to $0.12 per share. Short and her team knew this was not the first time the market believed Whole Foods had gone stale. In 2006, Whole Foods' stock had also declined 20% over fears of slowing growth and increasing competition, but had since bounced back and outperformed both its competition and the broader market (see Exhibit 7.1 for stock price performance). Nevertheless, it was time for Short and her team to discuss how the news altered their outlook for the company in a revised analyst report. The main point of discussion would certainly be whether Whole Foods still had a recipe for success. EXHIBIT 7.1 | Share Price Performance of Whole Foods Market Indexed to S&P 500 Index (January 2005 to $70 $60 $50 $40 $30 $20 $10 $0 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08 Jan-09 Jan-10 Jan-11 Jan-12 Jan-13 Jan-14 ..... S&P 500 Index matched to WFM Jan 05 Price Whole Foods Market April 2014) Data source: Yahoo! Finance, author analysis. Page 114 estimates for nominal long-term growth rate were between 2% and 3%.2 Key segments included conventional grocers such as Kroger, Publix, Safeway, and Albertsons; supercenters such as Wal-Mart and Target; natural grocers such as Whole Foods, Sprouts Farmers Market (Sprouts), and The Fresh Market (Fresh Market); and wholesalers such as Costco and Sam's Club. Conventional grocers remained the primary destination for shoppers, but competition from Wal-Mart, wholesalers, and other low-price vendors had driven down conventional grocers' share of food dollars for over a decade; for example, Wal-Mart was the largest food retailer in the United States in 2014, with 25% market share. Exhibit 7.2 provides market share information for the U.S. grocery market. The narrow margins and limited growth opportunities favored large competitors that could leverage efficiencies in purchasing and distribution to pass savings on to the consumer. As a result, many small competitors had been acquired or forced to close. Consumers were extremely price conscious and came to expect promotions (which were largely funded by manufacturers), and most shoppers did not have strong attachments to particular retail outlets. 2016 EXHIBIT 7.2 Select Market Share Data Grocery Sales by Channel Actual 2011 Traditional Supermarkets 40.1% Supercenters 17.2% Convenience Stores 15.1% Wholesale Clubs 8.5% Drug Stores 5.5% Mass Merchandisers Limited Assortment Grocery Stores 2.7% Dollar Stores 2.2% Other 4.3% 37.4% 18.5% 15.6% 9.0% 5.9% 2.8% 3.7% 2.3% 4.9% 2012 Revenue Top Grocery Retailers in North America ($ billions) Wal-Mart 145.0 Kroger 96.3 Costco 87.3 Targot 73.1 Safeway 445 Loblaw Cos 31.8 Publix 27.5 Ahold USA Retail 27.3 7-Eleven 22.0 C&S Wholesale Grocers 21.4 Delhaize America 19.5 H-E-B Grocery Co 19.4 Sobeys 17.7 Dollar General Corp. 16.1 Meijer, Inc. 146 Wakefern Food Corp. 13.6 Motro Inc. 12.0 Whole Foods Market 11.7 Source : Market Share Reporter (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014) and author analysis. Given this environment, companies relentlessly searched for opportunities to achieve growth and improve margins. Many grocers had implemented loyalty programs to reward repeat shoppers, and most were trying to improve the in-store customer experience, for instance by using self-checkout lines and other operational adjustments to reduce checkout times, a source of frequent complaints. Given the high percentage of perishable goods in the industry, supply chain management was essential, and companies were using improved technology to more efficiently plan their inventories. Grocers also began promoting prepared foods, which could command higher margins and reach consumers who did not regularly cook their own meals. Finally, most major grocers offered private-label products, which allowed them to offer low prices while still capturing sufficient margins. Despite operating in a competitive and low-growth industry, natural grocers had grown rapidly over the past two decades. Increasingly health-conscious consumers were concerned about the source and content of their food, which fueled natural grocers' sustained growth (over 20% per year since 1990) despite their comparatively higher prices. In 2012, natural and organic products accounted for $81 billion in total sales in the United States, a 10% increase from the previous year. Organic products, which were more narrowly defined than natural products, accounted for about $28 billion of these sales and were expected to top $35 billion by the end of 2014. Exhibit 7.3 provides growth forecast and share data on the natural and organic segments. As of 2014, 45% of Americans explicitly sought to include organic food in their meals, and more than half of the country's 1829-year-old population sought it out. By specializing in such products, natural grocers were able to carve out a profitable niche: the three leading natural grocers (Whole Foods, Sprouts, and Fresh Market) had EBITDA margins of 9.5%, 7.7%, and 9.1% respectively, whereas Kroger, the leading conventional Page 115 supermarket, had an EBITDA margin of only 4.5%. Exhibits 7.4 and 7.5 contain operating and financial information for selected companies in the U.S. grocery industry. EXHIBIT 7.3 U.S. Store Count Forecast-Natural and Organic Share versus Total Industry 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Conventional Supermarkets 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 Natural and Organic Subtotal 1,367 1,572 1,808 2,079 2391 2.750 Assumed Growth Rate 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% N&O Share of Industry 3.6% 4.2% 4.8% 5.4% 6.2% 7.1% Data source: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. EXHIBIT 7.4 Selected Operating Data for Comparable Companies Average Sales Growth 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10% -20% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Whole Foods Market Other Natural & Organic ---- Conventional Grocer ........ Supercenters and wholesalers Average EBITDA Margins 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Whole Foods Market ---- Conventional Grocer ---Other Natural & Organic ... Supercenters and wholesalers Note: "Other natural & organic" is composed of Sprouts and Fresh Market. "Conventional grocer" is composed of Kroger, Safeway, and SuperValu. "Supercenters and wholesalers" is composed of Wal-Mart and Costco. Source: Company SEC filings, 2003 - 2013 EXHIBIT 7.5 Selected Financial Data for Comparable Companies (in millions of USD, except percentages, ratios, and per share data; financial statement data as of fiscal year 2013) Market Cap Bond Credit Company Sales EBITDA of Equity Total Debt Beta Rating Natural & Organic Whole Foods Market 12.917 1.222 14,481 0 0.70 NA Sprouts Farmers Market 2.438 187 4,102 304 0.75 BB- The Fresh Market 1,512 138 1,554 25 0.80 NA Conventional Grocers Kroger 98.375 4,428 23.679 11,311 0.70 BBB Safoway 36,139 1,579 7,899 4.451 0.75 BBB Supervalu 17.155 720 1,876 2.531 1.00 B- Supercontors and Wholesalers Wal-Mart 476.294 35,742 251.747 55.245 0.60 AA Target 72.596 6,452 36.806 14.089 0.75 A Costco 105,156 3,999 49,257 4.985 0.75 A+ Data source: Company SEC filings: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. As expected, the segment's attractiveness sparked increasing competition from both new entrants and established players from the other competing segments. Wal-Mart, Kroger, and others launched organic offerings targeted at health-conscious consumers, often at a much lower price point than similar products at natural grocers. While Whole Foods, other natural grocers, independent retailers, and food cooperatives were the primary source of organic products in the 1990s, by 2006, half of the country's organic food was sold through conventional supermarkets. By 2014, organic products were available in over 20,000 natural food stores and nearly three out of four conventional grocers. Lo Even in the face of this competition, Whole Foods maintained a position as the market leader for the natural and organic industry. As many grocers joined the natural and organic bandwagon, Whole Foods defended against misrepresentative claims. Whole Foods had recently introduced a system to rate fresh produce on a number of criteria, including sustainability and other characteristics important to natural and organic customers. The company's website listed over 75 substances that were prohibited in all of its products and published additional measures for meat, seafood, and produce selection to ensure consumers had insight into the quality of their food. Whole Foods was the only U.S. retailer that labeled genetically modified foods, an area of some concern to health-conscious consumers. Despite its remarkable growth, the natural and organic industry was not without its critics. Several academic and government studies had concluded that organic products were not significantly more nutritious than nonorganic goods and claimed that the inefficiency of organic production could harm the environment. Moreover, the continuing lack of official legal definitions of terms such as "natural" arguably made them effectively meaningless: one botanist argued the segment was "99% marketing and public perception."12 Whole Foods Market Whole Foods traced its roots to 1978, when John Mackey and Renee Lawson opened a small organic grocer called Safer Way in Austin, Texas. Two years later, it partnered with Craig Weller and Mark Skiles of Clarksville Natural Grocery to launch the first Whole Foods Market, one of the country's first natural and organic supermarkets. In 1984, the company began expanding within Texas and in 1988 made its first move across state lines by acquiring the Louisiana-based Whole Foods Company, the next year it launched its first store Page 116 in California. The company went public in 1992 and grew rapidly during the 1990s through both new store openings and acquisitions. Whole Foods launched its first international store in Canada in 2002 and acquired a natural supermarket chain in the United Kingdom in 2004.13 The company had consistently maintained high growth throughout the new century by increasing same-store sales and expanding its store count; same-store sales grew more than 5% in every year except 2008 and 2009, when the global financial crisis brought America into a severe recession. By 2013, the company's growth strategy had moved away from acquisitions, and management saw improving same-store sales and continued new openings as its primary growth opportunities.14 Same-store sales-the most important growth criteria Wall Street used to evaluate retailers-had grown by at least 7% every year since 2010, far above other established grocers' growth rates even after it began expanding its natural and organic offerings. The company had done all of this with no debt financing. Looking forward, Whole Foods management planned to eventually operate over 1,000 stores, up from the 362 it operated as of the end of fiscal year 2013.15 Exhibit 7.6 contains store count and same-store sales growth history for Whole Foods and other industry players. EXHIBIT 7.6 Store Growth Statistics for Whole Foods and Other Industry Comparables 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Stores Trader Joe's 400 Whole Foods Market 275 284 299 311 335 362 Sprouts 36 40 43 103 148 167 Fresh Market 86 92 100 113 129 151 Natural Grocers 72 Fairway 14 Other Natural and Organic Retailers 200 Kroger 2,481 2,469 2,460 2,435 2.424 2.640 Safoway 1,739 1.725 1,694 1,678 1,641 1,335 SuperValu 2.474 2.421 2.349 2.394 2.434 2.396 Wal-Mart (including Sam's Club, U.S. only) 4.258 4360 4,413 4,479 4,625 4,835 Costco (US, Canada, & Mexico) 512 527 540 592 606 634 2013 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Same-Store Sales Growth Whole Foods Market 4.0% -40% 7.0% 8.0% 8.0% Sprouts 9.0% 2.6% 2.3% 5.1% 9.7% Fresh Market -1.5% -1.1% 5.0% 5.45 5.79 Kroger (excluding fuel 5.3% 3.1% 2.5% 4.9% 3.5% Safoway (excluding fuel) 1.5% -4.9% -0.5% 4.9% 1.6% SuperValu (including fuel) 0.5% -1.2% -5.1% -6.0% -2.8% Wal-Mart (U.S. only) 3.5% -0.8% -0.6% 1.6% 2.4% Costco (including fuel) 8.0% -4.0% 7.0% 10.0% 7.0% Data source: Company SEC filings: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. 7.0% 10.7% 3.2% 3.6% 0.2% -2.4% -0.5% 6.0% Whole Foods positioned itself as "the leading retailer of natural and organic foods and defined its mission as promoting "the vitality and well-being of all individuals by supplying the highest quality, most wholesome foods available.":16 The company's sole operating segment was its natural and organic markets and nearly 97% of its revenues came from the United States. By 2013, the average Whole Foods store carried 21,000 SKUs and approximately 30% of sales outside the bakery and prepared-food segments were organic. Whole Foods reported $551 million in net income on $12.9 billion in sales in 2013, making it the clear leader of natural and organic grocers even though its numbers were still rather small compared to Kroger's net income of $1.5 billion on more than $98 billion in sales. 12 Facing increased competition in the segment, many analysts believed that Whole Foods' biggest challenge was its reputation for high prices. For instance, Whole Foods charged $2.99 for a pound of organic apples, compared to $1.99 at Sprouts and even less at Costco. Indeed, many consumers derisively described the store as Whole Paycheck," and the company had historically opened its stores in high-income areas. In response to this image, the company had already begun marketing private labels (365 and 365 Everyday Value), begun competitive price matching and promotional sales, and launched a printed value guide (The Whole Deal) that featured coupons, low-budget recipes, and other tips for price-conscious consumers.19 Additionally, many Whole Foods supporters often pointed out that they were willing to pay a premium price for a premium product. Page 117 The Research Report The recent collapse of Whole Foods' stock price had caught Short and her team flatfooted. After all, heated competition in the grocery space was nothing new, even for Whole Foods, but the company had nonetheless maintained both its favorable margins and high growth rate for years. Short, along with many other analysts across Wall Street, had been strongly in the bull camp prior to the recent earnings report. Short's report from the past month recommended to investors that Whole Foods stock was a "buy" and worth $60 per share. This argument was based on ongoing gains to expected revenue growth and EBITDA margins in the coming year the report built in expectations of revenue growth of 11% and 14%, respectively, in 2014 and 2015; and EBITDA margins of 9.4% and 9.8%, respectively, in 2014 and 2015). The main question now facing the team was whether to adjust its financial forecast for Whole Foods in light of recent news. Exhibit 7.7 contains a version of the forecast model with the assumptions used for Short's previous report. As an additional benchmark, Exhibit 7.8 reports prevailing capital market information. As Short reconsidered her position, her team fleshed out the case for both a bearish and bullish view on Whole Foods. 6.7 EXHIBIT 7.7 Deutsche Bank Model (in millions of USD, except per share figures) Actual Actual Actual Forecast Forecast At Fiscal Year End 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Store Growth 4.0% 7.7% 8.1% 10.5% 12.6% Sales Growth 12.2% 15.7% 10.4% 11.1% 14.0% EBITDA Margin 8.5% 9.0% 9.5% 9.4% 9.8% Tax Rate 38.1% 38.4% 38.8% 39.0% 39.0% Current Asset Turnover 7.0 5.6 6.5 7.0 7.1 Current Liabilities Turnover 105 10.9 10.7 10.5 10.5 Net PP&E/Store 6.4 6.5 6.7 6.7 Annual Dep. & Amort/Store 1.00 0.93 0.94 0.94 0.94 Stores 311 335 362 400 450 Sales 10.108 11.699 12,917 14,351 16,360 859 1,055 1.222 1,352 1.600 Dep.& Amort 311 311 339 376 423 EBIT 548 744 883 976 1,176 Taxes 209 286 343 381 459 Net Income 339 458 540 717 Shares Outstanding 350 364 372 372 372 Earnings per Share 0.97 1.26 1.45 1.60 1.93 Current Assets 1,453 2.103 1.980 2.050 2.304 Current Liabilities 880 977 1,088 1.238 1,406 Net Working Capital 573 1,126 892 812 898 Net PP&E 1.997 2.193 2.428 2.680 3,018 Return on Capital 13.2% 16.3% 17.1% 18.3% Data source: Company financial reports, Deutsche Bank research, and author estimates. EBITDA 596 13.8% EXHIBIT 7.8 Demographic and Capital Markets Data U.S. Population Growth Rates 2014-2015 2015-2060 Compound Annual Growth Rate) Yield on U.S. Treasures 0.82% 0.70% 6 Months 1 Year 3 Years 5 Years 30 Years Average Yields on U.S. Corporate Bonds 0.05% 0.10% 0.90% 1.65% 3.40% 5-Year Maturity 30-Year Maturity AA BBB BB 1.90% 2.09% 2.49% 4.00% 4.90% 4.29% 4.39% 4 BOX 6.83% n/a Data sources: Bloomberg and U.S. Census Bureau From the bears' perspective, the natural and organic market was becoming saturated as more companies offered organic products at lower cost. This competition would soon compress Whole Foods' margins, while at the same time stealing market share and causing same-store sales to slow or even decline 20 Several analysts had downgraded Whole Foods after the company issued its disappointing quarterly results.21 A report put out the previous week by another bank noted that 85% of Whole Foods' stores were within three miles of a Trader Joe's -a privately owned natural grocer-up from 44% in 2005; similar overlap with Sprouts had grown from 3% to 16% and with Fresh Market from 1% to 14%. Moreover, Whole Foods was running out of dense, highly educated, high-income neighborhoods to open new stores in, which could either force the company to rely more on low-price offerings or slow its rapid expansion. 22 Such a shift in strategy could take the company into uncharted territory and risk its reputation as a premium brand. Finally, the bears were concerned that the new competitive reality would cause the market to fundamentally revalue Whole Foods. The company had long traded at a substantial premium, at times exceeding Kroger's market value, despite the latter company's substantial size advantage compared to Whole Foods, Kroger had 7.3 times as many stores that generated 7.6 times as many sales and 3.6 times as much EBITDA). Such a premium could only be justified if Whole Foods could continue growing, both at its existing stores and in terms of its overall footprint. The team noted that even if it cut the price target from $60 to $40, Whole Foods would still trade at a premium to its competitors in the Page 118 conventional grocers' segment. The bulls believed the combination of Whole Foods' leadership in natural and organic offerings, shifting consumer preferences, and organic food's small but rapidly growing market provided ample runway for sustained growth at high margins.23 As the clear leader in the segment, Whole Foods was well positioned to benefit from consumers' increasingly health-conscious decision making. Moreover, Whole Foods was not just another retailer that offered natural products; it was the standard bearer and thought leader for the industry, making it top of mind for anyone interested in the type of healthy products Whole Foods brought into the mainstream. Its competitors were merely imitating what Whole Foods pioneered and continued to lead, giving the company a sustainable advantage. 24 While competition could put downward pressure on some of Whole Foods' prices, the company had the stature to maintain its margin targets even with competitive price cuts by driving sales toward higher-margin categories like prepared foods, where the grocer could more readily differentiate its products. Moreover, the company's high prices gave it more room to adjust prices on goods where it directly competed with lower-cost retailers; past work by Short's team had shown that Whole Foods could match Kroger on 10,000 SKUs-equivalent to all the non private-label nonperishable products the company offered and still maintain nearly a 35% gross margin, which was within Whole Foods' target range 25 Similar analyses against other competitors also suggested ample room to selectively compete on prices while maintaining its overall margin targets. Additionally, Whole Foods had opportunities to reduce operating expenses, which the bulls thought would offset decline in revenue from pricing pressure over the next few years. While some analysts were concerned that Whole Foods' expansion would take it into lower-income areas that were distinct from the company's historical target market, the bulls believed that Whole Foods private-label products offered a chance to provide similar, high-quality products at a more accessible price point while protecting margins and providing a promising new avenue for growth. 26 While the bulls acknowledged that Whole Foods traded at a premium, they thought the company's higher growth rates, attractive margins, and position as a market leader provided ample justification for its higher valuation. Whole Foods' CEO John Mackey was firmly in the bull camp. While he acknowledged that Whole Foods best-in-the-industry sales per square foot and margins would attract competition, he claimed: We are and will be able to compete successfully and that the pricing gap between Whole Foods and the competition would not disappear.27 More importantly, he claimed that no competitor offered the quality of products that Whole Foods could, regardless of how these competitors chose to market their products. Alluding to the lack of a clear legal definition for natural foods, he alleged that many competitors marketed standard commercial meat and Page 119 other perishable goods under misleading labels, and said that Whole Foods could more aggressively advertise its superior quality to maintain its differentiation from the competition. Similarly, the company was making investments to improve the customer experience, already seen by many as one of its stronger points, by shortening wait times and offering higher-quality self-service food. Behind the scenes, it was reallocating support personnel on a regional rather than store-by-store basis in an effort to cut costs. After hinting at several projects in the pipeline that would help Whole Foods thrive in the new reality of stronger competition, he said that Whole Foods is not sitting still. We are still very innovative!" Page 113 CASE 7 Whole Foods Market: The Deutsche Bank Report The latest numbers coming out of Whole Foods Market, Inc. (Whole Foods) in May 2014 took Deutsche Bank research analyst Karen Short and her team by surprise. On May 6, Whole Foods reported just $0.38 per share in its quarterly earnings report, missing Wall Street's consensus of $0.41 and cutting earnings guidance for the remainder of the year. The company's share price fell 19% to $38.93 the next day as Whole Foods' management acknowledged that it faced an increasingly competitive environment that could compress margins and slow expansion. The only upbeat news was the 20% increase in the company's quarterly dividend, up from $0.10 to $0.12 per share. Short and her team knew this was not the first time the market believed Whole Foods had gone stale. In 2006, Whole Foods' stock had also declined 20% over fears of slowing growth and increasing competition, but had since bounced back and outperformed both its competition and the broader market (see Exhibit 7.1 for stock price performance). Nevertheless, it was time for Short and her team to discuss how the news altered their outlook for the company in a revised analyst report. The main point of discussion would certainly be whether Whole Foods still had a recipe for success. EXHIBIT 7.1 | Share Price Performance of Whole Foods Market Indexed to S&P 500 Index (January 2005 to $70 $60 $50 $40 $30 $20 $10 $0 Jan-05 Jan-06 Jan-07 Jan-08 Jan-09 Jan-10 Jan-11 Jan-12 Jan-13 Jan-14 ..... S&P 500 Index matched to WFM Jan 05 Price Whole Foods Market April 2014) Data source: Yahoo! Finance, author analysis. Page 114 estimates for nominal long-term growth rate were between 2% and 3%.2 Key segments included conventional grocers such as Kroger, Publix, Safeway, and Albertsons; supercenters such as Wal-Mart and Target; natural grocers such as Whole Foods, Sprouts Farmers Market (Sprouts), and The Fresh Market (Fresh Market); and wholesalers such as Costco and Sam's Club. Conventional grocers remained the primary destination for shoppers, but competition from Wal-Mart, wholesalers, and other low-price vendors had driven down conventional grocers' share of food dollars for over a decade; for example, Wal-Mart was the largest food retailer in the United States in 2014, with 25% market share. Exhibit 7.2 provides market share information for the U.S. grocery market. The narrow margins and limited growth opportunities favored large competitors that could leverage efficiencies in purchasing and distribution to pass savings on to the consumer. As a result, many small competitors had been acquired or forced to close. Consumers were extremely price conscious and came to expect promotions (which were largely funded by manufacturers), and most shoppers did not have strong attachments to particular retail outlets. 2016 EXHIBIT 7.2 Select Market Share Data Grocery Sales by Channel Actual 2011 Traditional Supermarkets 40.1% Supercenters 17.2% Convenience Stores 15.1% Wholesale Clubs 8.5% Drug Stores 5.5% Mass Merchandisers Limited Assortment Grocery Stores 2.7% Dollar Stores 2.2% Other 4.3% 37.4% 18.5% 15.6% 9.0% 5.9% 2.8% 3.7% 2.3% 4.9% 2012 Revenue Top Grocery Retailers in North America ($ billions) Wal-Mart 145.0 Kroger 96.3 Costco 87.3 Targot 73.1 Safeway 445 Loblaw Cos 31.8 Publix 27.5 Ahold USA Retail 27.3 7-Eleven 22.0 C&S Wholesale Grocers 21.4 Delhaize America 19.5 H-E-B Grocery Co 19.4 Sobeys 17.7 Dollar General Corp. 16.1 Meijer, Inc. 146 Wakefern Food Corp. 13.6 Motro Inc. 12.0 Whole Foods Market 11.7 Source : Market Share Reporter (Farmington Hills, MI: Gale, 2014) and author analysis. Given this environment, companies relentlessly searched for opportunities to achieve growth and improve margins. Many grocers had implemented loyalty programs to reward repeat shoppers, and most were trying to improve the in-store customer experience, for instance by using self-checkout lines and other operational adjustments to reduce checkout times, a source of frequent complaints. Given the high percentage of perishable goods in the industry, supply chain management was essential, and companies were using improved technology to more efficiently plan their inventories. Grocers also began promoting prepared foods, which could command higher margins and reach consumers who did not regularly cook their own meals. Finally, most major grocers offered private-label products, which allowed them to offer low prices while still capturing sufficient margins. Despite operating in a competitive and low-growth industry, natural grocers had grown rapidly over the past two decades. Increasingly health-conscious consumers were concerned about the source and content of their food, which fueled natural grocers' sustained growth (over 20% per year since 1990) despite their comparatively higher prices. In 2012, natural and organic products accounted for $81 billion in total sales in the United States, a 10% increase from the previous year. Organic products, which were more narrowly defined than natural products, accounted for about $28 billion of these sales and were expected to top $35 billion by the end of 2014. Exhibit 7.3 provides growth forecast and share data on the natural and organic segments. As of 2014, 45% of Americans explicitly sought to include organic food in their meals, and more than half of the country's 1829-year-old population sought it out. By specializing in such products, natural grocers were able to carve out a profitable niche: the three leading natural grocers (Whole Foods, Sprouts, and Fresh Market) had EBITDA margins of 9.5%, 7.7%, and 9.1% respectively, whereas Kroger, the leading conventional Page 115 supermarket, had an EBITDA margin of only 4.5%. Exhibits 7.4 and 7.5 contain operating and financial information for selected companies in the U.S. grocery industry. EXHIBIT 7.3 U.S. Store Count Forecast-Natural and Organic Share versus Total Industry 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Conventional Supermarkets 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 36,092 Natural and Organic Subtotal 1,367 1,572 1,808 2,079 2391 2.750 Assumed Growth Rate 15% 15% 15% 15% 15% N&O Share of Industry 3.6% 4.2% 4.8% 5.4% 6.2% 7.1% Data source: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. EXHIBIT 7.4 Selected Operating Data for Comparable Companies Average Sales Growth 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% -10% -20% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Whole Foods Market Other Natural & Organic ---- Conventional Grocer ........ Supercenters and wholesalers Average EBITDA Margins 10% 8% 6% 4% 2% 0% 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Whole Foods Market ---- Conventional Grocer ---Other Natural & Organic ... Supercenters and wholesalers Note: "Other natural & organic" is composed of Sprouts and Fresh Market. "Conventional grocer" is composed of Kroger, Safeway, and SuperValu. "Supercenters and wholesalers" is composed of Wal-Mart and Costco. Source: Company SEC filings, 2003 - 2013 EXHIBIT 7.5 Selected Financial Data for Comparable Companies (in millions of USD, except percentages, ratios, and per share data; financial statement data as of fiscal year 2013) Market Cap Bond Credit Company Sales EBITDA of Equity Total Debt Beta Rating Natural & Organic Whole Foods Market 12.917 1.222 14,481 0 0.70 NA Sprouts Farmers Market 2.438 187 4,102 304 0.75 BB- The Fresh Market 1,512 138 1,554 25 0.80 NA Conventional Grocers Kroger 98.375 4,428 23.679 11,311 0.70 BBB Safoway 36,139 1,579 7,899 4.451 0.75 BBB Supervalu 17.155 720 1,876 2.531 1.00 B- Supercontors and Wholesalers Wal-Mart 476.294 35,742 251.747 55.245 0.60 AA Target 72.596 6,452 36.806 14.089 0.75 A Costco 105,156 3,999 49,257 4.985 0.75 A+ Data source: Company SEC filings: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. As expected, the segment's attractiveness sparked increasing competition from both new entrants and established players from the other competing segments. Wal-Mart, Kroger, and others launched organic offerings targeted at health-conscious consumers, often at a much lower price point than similar products at natural grocers. While Whole Foods, other natural grocers, independent retailers, and food cooperatives were the primary source of organic products in the 1990s, by 2006, half of the country's organic food was sold through conventional supermarkets. By 2014, organic products were available in over 20,000 natural food stores and nearly three out of four conventional grocers. Lo Even in the face of this competition, Whole Foods maintained a position as the market leader for the natural and organic industry. As many grocers joined the natural and organic bandwagon, Whole Foods defended against misrepresentative claims. Whole Foods had recently introduced a system to rate fresh produce on a number of criteria, including sustainability and other characteristics important to natural and organic customers. The company's website listed over 75 substances that were prohibited in all of its products and published additional measures for meat, seafood, and produce selection to ensure consumers had insight into the quality of their food. Whole Foods was the only U.S. retailer that labeled genetically modified foods, an area of some concern to health-conscious consumers. Despite its remarkable growth, the natural and organic industry was not without its critics. Several academic and government studies had concluded that organic products were not significantly more nutritious than nonorganic goods and claimed that the inefficiency of organic production could harm the environment. Moreover, the continuing lack of official legal definitions of terms such as "natural" arguably made them effectively meaningless: one botanist argued the segment was "99% marketing and public perception."12 Whole Foods Market Whole Foods traced its roots to 1978, when John Mackey and Renee Lawson opened a small organic grocer called Safer Way in Austin, Texas. Two years later, it partnered with Craig Weller and Mark Skiles of Clarksville Natural Grocery to launch the first Whole Foods Market, one of the country's first natural and organic supermarkets. In 1984, the company began expanding within Texas and in 1988 made its first move across state lines by acquiring the Louisiana-based Whole Foods Company, the next year it launched its first store Page 116 in California. The company went public in 1992 and grew rapidly during the 1990s through both new store openings and acquisitions. Whole Foods launched its first international store in Canada in 2002 and acquired a natural supermarket chain in the United Kingdom in 2004.13 The company had consistently maintained high growth throughout the new century by increasing same-store sales and expanding its store count; same-store sales grew more than 5% in every year except 2008 and 2009, when the global financial crisis brought America into a severe recession. By 2013, the company's growth strategy had moved away from acquisitions, and management saw improving same-store sales and continued new openings as its primary growth opportunities.14 Same-store sales-the most important growth criteria Wall Street used to evaluate retailers-had grown by at least 7% every year since 2010, far above other established grocers' growth rates even after it began expanding its natural and organic offerings. The company had done all of this with no debt financing. Looking forward, Whole Foods management planned to eventually operate over 1,000 stores, up from the 362 it operated as of the end of fiscal year 2013.15 Exhibit 7.6 contains store count and same-store sales growth history for Whole Foods and other industry players. EXHIBIT 7.6 Store Growth Statistics for Whole Foods and Other Industry Comparables 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Total Stores Trader Joe's 400 Whole Foods Market 275 284 299 311 335 362 Sprouts 36 40 43 103 148 167 Fresh Market 86 92 100 113 129 151 Natural Grocers 72 Fairway 14 Other Natural and Organic Retailers 200 Kroger 2,481 2,469 2,460 2,435 2.424 2.640 Safoway 1,739 1.725 1,694 1,678 1,641 1,335 SuperValu 2.474 2.421 2.349 2.394 2.434 2.396 Wal-Mart (including Sam's Club, U.S. only) 4.258 4360 4,413 4,479 4,625 4,835 Costco (US, Canada, & Mexico) 512 527 540 592 606 634 2013 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Same-Store Sales Growth Whole Foods Market 4.0% -40% 7.0% 8.0% 8.0% Sprouts 9.0% 2.6% 2.3% 5.1% 9.7% Fresh Market -1.5% -1.1% 5.0% 5.45 5.79 Kroger (excluding fuel 5.3% 3.1% 2.5% 4.9% 3.5% Safoway (excluding fuel) 1.5% -4.9% -0.5% 4.9% 1.6% SuperValu (including fuel) 0.5% -1.2% -5.1% -6.0% -2.8% Wal-Mart (U.S. only) 3.5% -0.8% -0.6% 1.6% 2.4% Costco (including fuel) 8.0% -4.0% 7.0% 10.0% 7.0% Data source: Company SEC filings: Deutsche Bank Research: Food Marketing Institute. 7.0% 10.7% 3.2% 3.6% 0.2% -2.4% -0.5% 6.0% Whole Foods positioned itself as "the leading retailer of natural and organic foods and defined its mission as promoting "the vitality and well-being of all individuals by supplying the highest quality, most wholesome foods available.":16 The company's sole operating segment was its natural and organic markets and nearly 97% of its revenues came from the United States. By 2013, the average Whole Foods store carried 21,000 SKUs and approximately 30% of sales outside the bakery and prepared-food segments were organic. Whole Foods reported $551 million in net income on $12.9 billion in sales in 2013, making it the clear leader of natural and organic grocers even though its numbers were still rather small compared to Kroger's net income of $1.5 billion on more than $98 billion in sales. 12 Facing increased competition in the segment, many analysts believed that Whole Foods' biggest challenge was its reputation for high prices. For instance, Whole Foods charged $2.99 for a pound of organic apples, compared to $1.99 at Sprouts and even less at Costco. Indeed, many consumers derisively described the store as Whole Paycheck," and the company had historically opened its stores in high-income areas. In response to this image, the company had already begun marketing private labels (365 and 365 Everyday Value), begun competitive price matching and promotional sales, and launched a printed value guide (The Whole Deal) that featured coupons, low-budget recipes, and other tips for price-conscious consumers.19 Additionally, many Whole Foods supporters often pointed out that they were willing to pay a premium price for a premium product. Page 117 The Research Report The recent collapse of Whole Foods' stock price had caught Short and her team flatfooted. After all, heated competition in the grocery space was nothing new, even for Whole Foods, but the company had nonetheless maintained both its favorable margins and high growth rate for years. Short, along with many other analysts across Wall Street, had been strongly in the bull camp prior to the recent earnings report. Short's report from the past month recommended to investors that Whole Foods stock was a "buy" and worth $60 per share. This argument was based on ongoing gains to expected revenue growth and EBITDA margins in the coming year the report built in expectations of revenue growth of 11% and 14%, respectively, in 2014 and 2015; and EBITDA margins of 9.4% and 9.8%, respectively, in 2014 and 2015). The main question now facing the team was whether to adjust its financial forecast for Whole Foods in light of recent news. Exhibit 7.7 contains a version of the forecast model with the assumptions used for Short's previous report. As an additional benchmark, Exhibit 7.8 reports prevailing capital market information. As Short reconsidered her position, her team fleshed out the case for both a bearish and bullish view on Whole Foods. 6.7 EXHIBIT 7.7 Deutsche Bank Model (in millions of USD, except per share figures) Actual Actual Actual Forecast Forecast At Fiscal Year End 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Store Growth 4.0% 7.7% 8.1% 10.5% 12.6% Sales Growth 12.2% 15.7% 10.4% 11.1% 14.0% EBITDA Margin 8.5% 9.0% 9.5% 9.4% 9.8% Tax Rate 38.1% 38.4% 38.8% 39.0% 39.0% Current Asset Turnover 7.0 5.6 6.5 7.0 7.1 Current Liabilities Turnover 105 10.9 10.7 10.5 10.5 Net PP&E/Store 6.4 6.5 6.7 6.7 Annual Dep. & Amort/Store 1.00 0.93 0.94 0.94 0.94 Stores 311 335 362 400 450 Sales 10.108 11.699 12,917 14,351 16,360 859 1,055 1.222 1,352 1.600 Dep.& Amort 311 311 339 376 423 EBIT 548 744 883 976 1,176 Taxes 209 286 343 381 459 Net Income 339 458 540 717 Shares Outstanding 350 364 372 372 372 Earnings per Share 0.97 1.26 1.45 1.60 1.93 Current Assets 1,453 2.103 1.980 2.050 2.304 Current Liabilities 880 977 1,088 1.238 1,406 Net Working Capital 573 1,126 892 812 898 Net PP&E 1.997 2.193 2.428 2.680 3,018 Return on Capital 13.2% 16.3% 17.1% 18.3% Data source: Company financial reports, Deutsche Bank research, and author estimates. EBITDA 596 13.8% EXHIBIT 7.8 Demographic and Capital Markets Data U.S. Population Growth Rates 2014-2015 2015-2060 Compound Annual Growth Rate) Yield on U.S. Treasures 0.82% 0.70% 6 Months 1 Year 3 Years 5 Years 30 Years Average Yields on U.S. Corporate Bonds 0.05% 0.10% 0.90% 1.65% 3.40% 5-Year Maturity 30-Year Maturity AA BBB BB 1.90% 2.09% 2.49% 4.00% 4.90% 4.29% 4.39% 4 BOX 6.83% n/a Data sources: Bloomberg and U.S. Census Bureau From the bears' perspective, the natural and organic market was becoming saturated as more companies offered organic products at lower cost. This competition would soon compress Whole Foods' margins, while at the same time stealing market share and causing same-store sales to slow or even decline 20 Several analysts had downgraded Whole Foods after the company issued its disappointing quarterly results.21 A report put out the previous week by another bank noted that 85% of Whole Foods' stores were within three miles of a Trader Joe's -a privately owned natural grocer-up from 44% in 2005; similar overlap with Sprouts had grown from 3% to 16% and with Fresh Market from 1% to 14%. Moreover, Whole Foods was running out of dense, highly educated, high-income neighborhoods to open new stores in, which could either force the company to rely more on low-price offerings or slow its rapid expansion. 22 Such a shift in strategy could take the company into uncharted territory and risk its reputation as a premium brand. Finally, the bears were concerned that the new competitive reality would cause the market to fundamentally revalue Whole Foods. The company had long traded at a substantial premium, at times exceeding Kroger's market value, despite the latter company's substantial size advantage compared to Whole Foods, Kroger had 7.3 times as many stores that generated 7.6 times as many sales and 3.6 times as much EBITDA). Such a premium could only be justified if Whole Foods could continue growing, both at its existing stores and in terms of its overall footprint. The team noted that even if it cut the price target from $60 to $40, Whole Foods would still trade at a premium to its competitors in the Page 118 conventional grocers' segment. The bulls believed the combination of Whole Foods' leadership in natural and organic offerings, shifting consumer preferences, and organic food's small but rapidly growing market provided ample runway for sustained growth at high margins.23 As the clear leader in the segment, Whole Foods was well positioned to benefit from consumers' increasingly health-conscious decision making. Moreover, Whole Foods was not just another retailer that offered natural products; it was the standard bearer and thought leader for the industry, making it top of mind for anyone interested in the type of healthy products Whole Foods brought into the mainstream. Its competitors were merely imitating what Whole Foods pioneered and continued to lead, giving the company a sustainable advantage. 24 While competition could put downward pressure on some of Whole Foods' prices, the company had the stature to maintain its margin targets even with competitive price cuts by driving sales toward higher-margin categories like prepared foods, where the grocer could more readily differentiate its products. Moreover, the company's high prices gave it more room to adjust prices on goods where it directly competed with lower-cost retailers; past work by Short's team had shown that Whole Foods could match Kroger on 10,000 SKUs-equivalent to all the non private-label nonperishable products the company offered and still maintain nearly a 35% gross margin, which was within Whole Foods' target range 25 Similar analyses against other competitors also suggested ample room to selectively compete on prices while maintaining its overall margin targets. Additionally, Whole Foods had opportunities to reduce operating expenses, which the bulls thought would offset decline in revenue from pricing pressure over the next few years. While some analysts were concerned that Whole Foods' expansion would take it into lower-income areas that were distinct from the company's historical target market, the bulls believed that Whole Foods private-label products offered a chance to provide similar, high-quality products at a more accessible price point while protecting margins and providing a promising new avenue for growth. 26 While the bulls acknowledged that Whole Foods traded at a premium, they thought the company's higher growth rates, attractive margins, and position as a market leader provided ample justification for its higher valuation. Whole Foods' CEO John Mackey was firmly in the bull camp. While he acknowledged that Whole Foods best-in-the-industry sales per square foot and margins would attract competition, he claimed: We are and will be able to compete successfully and that the pricing gap between Whole Foods and the competition would not disappear.27 More importantly, he claimed that no competitor offered the quality of products that Whole Foods could, regardless of how these competitors chose to market their products. Alluding to the lack of a clear legal definition for natural foods, he alleged that many competitors marketed standard commercial meat and Page 119 other perishable goods under misleading labels, and said that Whole Foods could more aggressively advertise its superior quality to maintain its differentiation from the competition. Similarly, the company was making investments to improve the customer experience, already seen by many as one of its stronger points, by shortening wait times and offering higher-quality self-service food. Behind the scenes, it was reallocating support personnel on a regional rather than store-by-store basis in an effort to cut costs. After hinting at several projects in the pipeline that would help Whole Foods thrive in the new reality of stronger competition, he said that Whole Foods is not sitting still. We are still very innovative

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts