Question: Please help summarize the article. Then, respond to the main questions, Why does this matter in the teaching and learning of mathematics? and How does

Please help summarize the article. Then, respond to the main questions, "Why does this matter in the teaching and learning of mathematics?" and "How does this article inform math teaching practice?

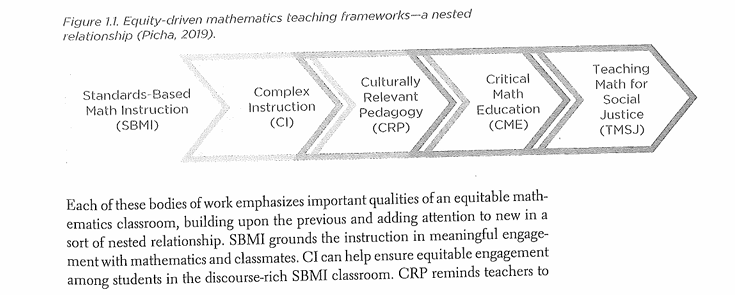

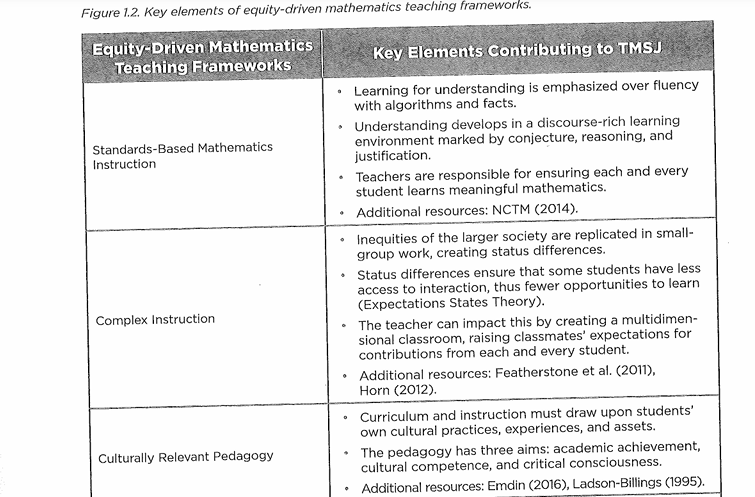

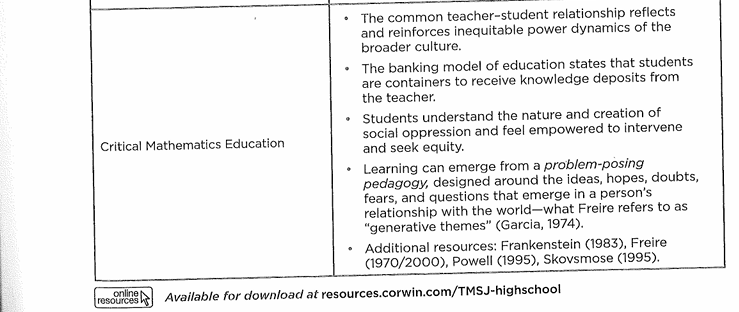

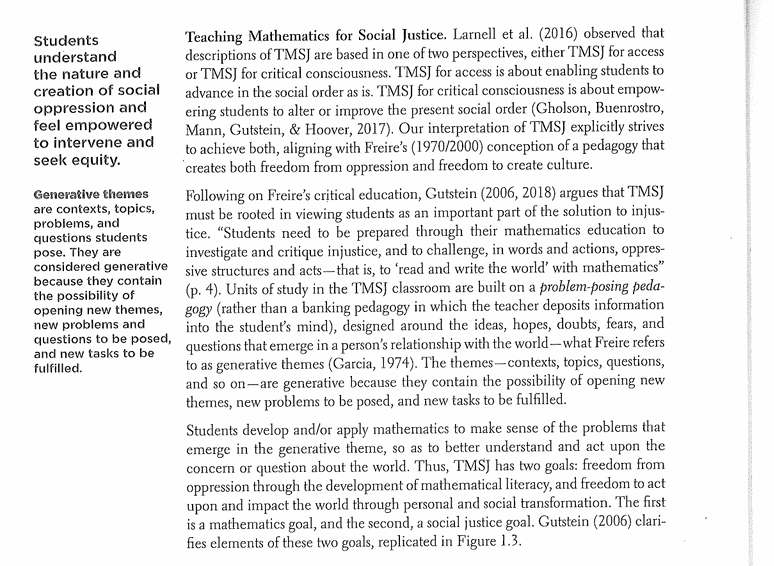

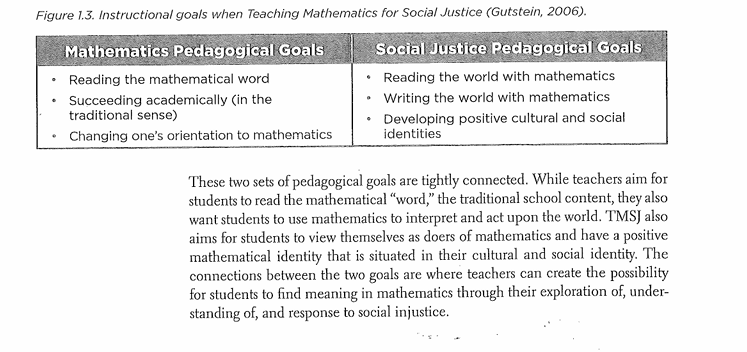

WHAT IS SOCIAL JUSTICE, AND WHY DOES IT MATTER IN TEACHING MATHEMATICS? Picture this: a Southern community in which high school students learned in the local newspaper about a once vibrant Black! community with businesses, churches, and community centers that had at one time served the community. The articles spotlighted people who once lived and served this community. Upon reading these stories in the local press, the high school students questioned what happened to this community and investigated how the once majority-Black neigh- borhood in their city had been bulldozed in the 1960s to make way for urban renewal projects. The results of this investigation led students toward unpacking not only the historical and economic impact on the Black community, but also the present-day effects such as quality schooling, jobs, access to affordable hous- ing, and policing policies. Discussion and debate of the local news have long been essential elements of the fabric that holds communities together. Newspapers and other media outlets often present opportunities for teachers and community mem- bers to pose questions situating mathematics as a tool for understanding and inves- tigating social injustice. Many local papers offer news and events that may not be of interest to another locality or nationally. For the students engaged in this investigation, the intersections between history, geography, and mathematics undergirded many of their questions. Teachers designed lessons in which students used geopolitical mapping to investigate pop- ulation density within their community to note the displacement of Black com- munity members over time. That is, many Black people at one time lived in the city, but because of displacement, they were now settled in communities farther away, reducing access to jobs, With the support of community members, students also requested data from their local police on citizens who were \"stopped and questioned.\" Their investigation of the data suggested that Black members of the communily were overrepresented in those stops by police. ! Through this book and the lessons included, we have intentionally capitalized terms used for people of Color, such as Black, while leaving white written in lower case. We follow Frances Harper (2019), one of the contributing authors to this book, in her rationale: "I chose to capitalize Color but not white to challenge the ways that these standard grammar conventions reinforee systems of privilege and oppression\" (p. 268). E The studentled work described above led to community actions and calls for social justice. The calls consisted of petitioning community leaders for plans for affordable housing, antibias training for community leaders, and gatherings for community members to connect with and learn from one another. Most impor- tantly, the students felt empowered to be change agents within their community by educating the broader community about what they had learned. Being knowledgeable about the histories, cultural conditions, and contexts of communities helps teachers access student and community funds of knowledge to incorporate into their teaching, By building upan these funds of knowledge, teachers can make the most of these family and community histories as intellec- tual and educational resources that can support mathematics teaching and learn- ing (Gonzdlez, Moll, & Amanti, 2005). Understanding the funds of knowledge in communities and families requires teachers to become active in students' com- munities. Thus, we must come to learn how to co-construct learning opportunities with communities and families. Imagine a classroom in which teachers, students, and community leaders collaborated using mathematics and other subject areas in the school to understand local issues. For example, what would it look like if these collaborations investigated food deserts in their communities, explored the allocation of public monies to fund public spaces, and studied population growth (or decline) to understand the use of community resources? Mathematics is a tool that cultures have developed and shaped to understand, quantify, critique, and make sense of the world. Consequently, mathematics is a human activity that should cultivate in students a sense of wonder, beauty, and joy (NCTM, 2018). Furthermore, students' mathematical activity empowers them to identify, interpret, evaluate, and critique the mathematics embedded in social, scientific, commercial, and political systems. Empowered students examine the claims made in the private and public sectors, and the pronouncements of public interest (Ernest, 2010). Students can become empowered when they have access to deep, rigorous mathematics that offers opportunities to understand and use mathematics in their world. This is achieved when the mathematics they study in school integrates topics that help them investigate and understand social injus- tices and equity (Stinson & Wager, 2012). For example, tasks that address income distributions, sustainability, mortality rates, taxing structures, or lending practices present opportunities for empowerment and social justice. Until recently, embedding mathematics pedagogy within social and political contexts was not a serious consideration in mathematics education. The act of counting was viewed as a neutral exercise, unconnected to politics or sociely. Yet when do we ever count just for the sake of counting? Only in school do we count without a social purpose of some kind. Ouside of school, mathematics is used to advance or block a particular agenda. (Tate, 2013, p. 48) Empowering students to use mathematies to critique and understand the world requires teachers to take a social justice position. Larnell, Bullock, and Jett (2016) remind us that, \"whether inside or outside of school, mathematics is political\" Students' mathematical activity empowers them o identify, interpret, evaluate, and critigque the imathematics embedded in social, scientific, commercial, and political systems. Choosing not to incorporate tasks that require students to critique and understand the world is itself a political position, one of political passivity. (p. 26; see also Gutirrez, 2013). That is, choosing not to incorporate tasks that require students to critique and understand the world is itself a political position, one of political passivity. Conversely, choosing to incorporate those tasks is an act of empowerment. Lessons in this book seek to have students engage in the socio- political reality that is meaningful and important to them, and to use mathemati- cal tools to answer questions emerging in these sociopolitical contexts that relate to their own, their classmates', and others' lives. When students have opportunities to use mathematics to solve problems in their everyday lives, they are empowered to engage in political and social acts as a way to seek justice. WHAT DO WE MEAN BY SOCIAL JUSTICE? Many different communities, each with diverse perspectives, make significant - contributions to society. For us as authors of this book, social justice means con- sidering the contributions and rights of each and every person in society across four ideas: access, participation, empowerment, and human rights. o Access: Ensuring access to and the fair distribution of human and material resources in society. e Participation: Creating equitable opportunities for people to access information to be fully participatory in decisions that affect their and others' lives, o Empowerment: Supporting people's sense of agency in taking advantage of opportunities society affords as well as working toward eliminating all forms of oppression, Human Rights: Acknowledging the rights inherent to each and every human being, regardless of race, sex, gender, nationality, ethnicity, lan- guage, religion, or any other status. Human rights include the right to life and liberty, freedom from slavery and torture, freedom of opinion and expression, the right to work and education, and many more (United Nations, 2006). The Center for Economic and Social Justice (n.d.) situates social justice as a virtue that guides people as they institutionalize organized human interactions. Social justice instills within each person a responsibility to collaborate with others for the common good and to perfect institutions as tools for personal and social development. And while the United Nations (2006) has defined social justice as \"the fair and compassionate distribution of the fruits of economic growth\" (p. 7), social justice must also attend to the distribution of social and political rights. Feagin (2001b) offered such a definition for social justice: As I see it, social justice requires resource equity, faimess, and respect for diversity, as well as the eradication of existing forms of social oppression. Sacial justice entails a redistribution of resources from those who have unjustly gained them to those who justly deserve them, and it also means creating and ensuring the processes of truly democratic participation in decision-making, . . . It seems clear that only a decisive redistribution of resources and decision-making power can ensure social justice and authen- tic democracy. (p. 5) These definitions of social justice require us to think about how people connect to one another, how resources get distributed, and the meaning of fairness. For us, social justice emphasizes the relations between the individual and sociely, and that they are to be fair and just, meaning that society has a responsibility to ensure equal rights, equal opportunity, and equal treatment for each and every individual. Living up to this responsibility means acting upon or responding to instances of injustice. This idea resonates with the joint position paper by the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics and TODOS: Mathematics for ALL (2016), as well as the position paper of the Benjamin Banneker Association (2017), both of which argue that embracing social justice moves us beyond notic- ing issues and concerns about societal inequities and requires actions that con- front oppression and/or marginalization and hence, our choice to title the book to explore, understand, and respond to social injustice. WHAT IS TEACHING MATHEMATICS FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE? Building on the ideas of social justice; society's responsibility to ensure equal rights, opportunity, and treatment; and the responsibility to respond, teaching mathematics for social justice (TMS]) is about teachers emphasizing equitable opportunities for each and every student, as well as developing an orientation toward using mathematics to enact decision-making power. This view of TMS] builds upon four other bodies of work having to do with equitable mathemat- ics teaching: Standards-Based Mathematics Instruction (SBMI), Complex Instruction (CI), Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (CRP), and Critical Mathematics Education (CME) (Figure 1.1). Embracing social justice moves us bheyoncd noticing issues and concerns aboui societal inequities and racjuires actions ihat confront oppression and/or inarginalization. Figure 1.1. Equity-driven mathematics teaching frameworks-a nested relationship (Picha, 2019). Culturally Critical Teaching Standards-Based Complex Math for Relevant Math Math Instruction Instruction Social Pedagogy Education (SBMI) (CD) Justice (CRP) (CME) (TMSJ) Each of these bodies of work emphasizes important qualities of an equitable math- ematics classroom, building upon the previous and adding attention to new in a sort of nested relationship. SBMI grounds the instruction in meaningful engage- ment with mathematics and classmates. CI can help ensure equitable engagement among students in the discourse-rich SBMI classroom. CRP reminds teachers todraw upon cultural practices, experiences, and assets, and it challenges them to awaken students' critical consciousness, CME provides teachers with a framework to design instruction to build eritical consciousness, and TMS] provides the how. Some key ideas from each of these five nested fra meworks are discussed next. Standards-Based Mathematics Instruction. TMS] must be grounded in peda- gogical principles widely recognized by the profession, referred to as SBML These principles emphasize learning for understanding over attending only to fluency with algorithms and facts. A second point of emphasis is the recognition that understanding develops in a discourse-rich learning environment marked by con- jecture, reasoning, and justification (Rubel, 2017). Paired with these ideas about what to learn and how to learn is an emphasis on the responsibility to ensure each and every student learns meaningful mathematics (NCTM, 1989, Complex Instruction. Sociologists (Cohen & Lotan, 2014) recognized that the inequities of the larger sociely are replicated in small groups, systematically ensur- ing that some students have less access to the discourse-rich SBMI classroom, and thus fewer opportunities to learn. CI is a pedagogical theory to counteract this trend. A key feature of Cl is valuing many different ways of being mathematically \"smart\" (Featherstone etal., 2011). In this sort o \"multidimensional\" mathemat- ics classroom (Boaler, 2006), the teacher has more opportunity to raise the low- ered expectations students may have for members of their group, inviting greater access to interactions for the otherwise excluded student. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Both SBMI and Cl attend to shifts in curriculum and teaching that ensure each and every student has opportunities to learn mathe- matics. By studying effective teachers, Ladson-Billings (1994/2009) recognized that they built upon each child's unique strengths, mathematical as well as social and cultural assets. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy (Ladson-Billings, 1995) reminds us to ensure that equitable instruction must draw upon students' cultural practices, expe- riences, and assets. As these cultural experiences and artifacts become central to the process of learning, students see themselves and their interests in the curriculum (Thomas & Berry, 2019). Thus, not only is academic achievement valued, but so is the growth of students\" cultural competence and eritical consciousness. Critical Mathematics Education. CME extends the idea of critical conscious- ness identified by CRP. This body of work is about teaching mathematics in such a way that it attends to the concerns of fairness and social justice in the relations between the individual and the society. It centers learning as identity work (Rubel, 2017) focused on who the student is becoming. These perspectives often build upon the pedagogical practices developed by Paulo Freire (1970/2000) in the Brazilian context. Freire described critical consciousness (his term is conscientizagdo, or conscien- tization) as \"a capacity to confront reality as transformable, and to intervene sub- sequently in it to effect that transformation\" (Garcia, 1974, p. 15). Freire's critical education puts an emphasis on a shift in the power dynamic between student and teacher, shifting the authority for knowledge to the social context of the classroom community rather than the teacher. Students are positioned as doers, or authors Figure 1.2. Key elements of equity-driven mathematics teaching frameworks. Equity-Driven Mathematics Teaching Frameworks Key Elements Contributing to TMSJ Learning for understanding is emphasized over fluency with algorithms and facts. Understanding develops in a discourse-rich learning Standards-Based Mathematics environment marked by conjecture, reasoning, and Instruction justification. Teachers are responsible for ensuring each and every student learns meaningful mathematics. Additional resources: NCTM (2014). Inequities of the larger society are replicated in small- group work, creating status differences. Status differences ensure that some students have less access to interaction, thus fewer opportunities to learn (Expectations States Theory). Complex Instruction The teacher can impact this by creating a multidimen sional classroom, raising classmates' expectations for contributions from each and every student. . Additional resources: Featherstone et al. (2011), Horn (2012). Curriculum and instruction must draw upon students' own cultural practices, experiences, and assets. Culturally Relevant Pedagogy The pedagogy has three aims: academic achievement, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. . Additional resources: Emdin (2016), Ladson-Billings (1995).The common teacher-student relationship reflects and reinforces inequitable power dynamics of the broader culture. . The banking model of education states that students are containers to receive knowledge deposits from the teacher. Students understand the nature and creation of Critical Mathematics Education social oppression and feel empowered to intervene and seek equity. . Learning can emerge from a problem-posing pedagogy, designed around the ideas, hopes, doubts, fears, and questions that emerge in a person's relationship with the world-what Freire refers to as "generative themes" (Garcia, 1974). . Additional resources: Frankenstein (1983), Freire (1970/2000), Powell (1995), Skovsmose (1995). online resources Available for download at resources.corwin.com/TMSJ-highschoolStudents understand the nature and creation of social oppression and feel empowered to intervene and seel equity. Generative themes are contexts, topics, problems, and quastions students pose. They are considered generative because they contain the possibility of opening new themes, new problems and guestions to be posed, and new tasks to be fulfilled. Teaching Mathematics for Social Justice. Larnell et al. (2016) observed that descriptions of TMS] are based in one of two perspectives, either TMS] for access or TMS] for critical consciousness. TMS] for access is about enabling students to advance in the social order as is. TMS] for critical consciousness is about empow- ering students to alter or improve the present social order (Gholson, Buenrostro, Mann, Gutstein, & Hoover, 2017). Our interpretation of TMS] explicitly strives to achieve both, aligning with Freire's (1970/2000) conception of a pedagogy that 'creates both freedom from oppression and freedom to create culture. Following on Freire's critical education, Gutstein (2006, 2018) argues that TMS] must be rooted in viewing students as an important part of the solution to injus- tice. \"Students need to be prepared through their mathematics education to investigate and critique injustice, and to challenge, in words and actions, oppres- sive structures and actsthat is, to 'read and write the world' with mathematics\" (p. 4). Units of study in the TMS] classroom are built on a problem-posing peda- gogy (rather than a banking pedagogy in which the teacher deposits information into the student's mind), designed around the ideas, hopes, doubts, fears, and questions that emerge in a person's relationship with the worldwhat Freire refers to as generative themes (Garcia, 1974). The themescontexts, topics, questions, and so onare generative because they contain the possibility of opening new themes, new problems to be posed, and new tasks to be fulfilled. Students develop and/or apply mathematics to make sense of the problems that emerge in the generative theme, so as to better understand and act upon the concern or question about the world. Thus, TMS] has two goals: freedom from oppression through the development of mathematical literacy, and freedom to act upon and impact the world through personal and social transformation. The first is a mathematics goal, and the second, a social justice goal. Gutstein (2006) clari- fies elements of these two goals, replicated in Figure 1.3. Figure 1.3. Instructional goals when Teaching Mathematics for Social Justice (Gutstein, 2006). T e e * Reading the world with mathematics Writing the world with mathematics + Developing positive cultural and social identities = Reading the mathematical word Succeeding academically (in the traditional sense) Changing one's orientation to mathematics These two sets of pedagogical goals are tightly connected. While teachers aim for students to read the mathematical \"word,\" the traditional school content, they also want students to use mathematics to interpret and act upon the world. TMS] also aims for students to view themselves as doers of mathematies and have a positive mathematical identity that is situated in their cultural and social identity. The connections between the two goals are where teachers can create the possibility for students to find meaning in mathematics through their exploration of, under- standing of, and response to social injustice. Through the model of the multiple teaching frameworks that contribute to TMS], we aim to emphasize our view that TMS] is much more than the lessons teachers might implement in their classrooms. Itis about the relationships they build with and among students; the teaching practices that help them do that; and the goals to develop posi- tive social, cultural, and mathematics identitiesas authors, actors, and doers. WHY SOCIAL JUSTICE IN MATHEMATICS EDUCATION? When teachers focus only on teaching mathematics, disconnects can oceur between the content and students' passions and lived realities. Contextualizing mathematics instruction in students' experiences of social injustice helps them become more interested in mathematics (Rubel, 2017). Furthermore, TMS] supports students' use of mathematics to better understand social injustices they recognize in their lives, and to be able to act upon those injustices. In doing so, students learn more mathematics. So why bring social injustices into the mathematics classroom? Besides offer- ing critical issues for students to examine and serving as context for mathematics development and investigation, four other answers to this question resonate with us. Teaching mathematics for social justice helps to o build an informed society, s connect mathematics with students' cultural and community histories, empower students to confront and solve real-world challenges they face, and o help students learn to value mathematics as a tool for social change. Fach of these rationales to TMS] resonates with the foundations of a public edu- cation, effective instructional practices, and a purpose for mathematics education shared by mathematics teachers everywhere. Build an Informed Society. To create a just society, students must become better informed about not only their own lives, but also the lives of others that may be differ- ent from their own. It is paramount that students connect to the injustices expressed by members of their school, community, city, and conntryespecially to injustices they may be unaware of as experienced by people with different social and cultural experiences from them. Mathematics serves a special role in informing and educat- ing citizens of these issues. By exploring the context of important issues and relating them to mathematics, students become aware of how mathematics may be used to help them better understand the issue, possibly sorting through misconceptions and thetoric. A student with a meaningful mathematics education is not just academi- cally successful (academic achievement in CRP; Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995), but also prepared to make informed decisions in a modern, ever-changing society. Connect Mathematics With Students' Cultural and Community Histories. Too often, students experience mathematics in schools as something detached from meaningful contexts; thus, they perceive it as unfamiliar and unimportant. This leaves many of them with the sense that mathematics is inaccessible and not connected to them or who and what they value. Students bring with them to the mathematics classroom a wealth of informal mathematical knowledge in their everyday cultural and social experiences, and that knowledge and those experi- ences are valuable resources for mathematics teaching and learning, We know that when classroom experiences and reasoning are meaningfully connected to students' ways of knowing, the learning that occursboth cognitively and cultur- - allyis powerful and lasting (National Research Council [NRC], 2000). By ground- ing learning in students' own cultural and community histories, a teacher has the opportunity to create both deeper knowledge and greater valuation of students' own culture, the sort of cultural competence called for by Ladson-Billings and Tate (1995). Empower Students to Confront and Solve Real-World Challenges They Tace. TMSJ helps students to build a critical consciousness, identifying issues that are unjust (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995), and then to use mathematics as a tool to ana- lyze, critique, and confront those unjust contexts. The teacher's role is to learn about his or her students to identify generative themes, and thus help them to uncover and explore the issues of injustice their families and communities face. One of our les- son authors provided a few specific strategies to develop critical consciousness. TEACHING FOR CRITICAL CONSCIOUSNESS by Shakiyya Bland, author of Bringing Healthy Food Choices to the Desert In their book chapter, Arellano, Cintrn, Flores, and Berta-Avila (2016) offer topics, themes, frameworks, and instructional activities to teach for critical consciousness. A few that stand out are as follows: o Advocate for a social justice perspective across school, communilty, and political contexts. Use and further develop students' cultural funds of knowledge. Lead students to achieve at academically high standards across the core curriculum. Guide students to explore issues of prejudice, discrimination, and mul- tiple forms of oppression involving people of different races, socioeco- nomic classes, language varieties, abilities and disabilities, and sexual orientation. . Engage students in naming, interrogating, and transforming. Promote school transformation toward equity and social justice on multiple levels. Help Students Learn to Value Mathematics as a Tool for Social Change. The potential of education is to support students to create better lives for themselves and a better society for each and every individual. Mathematics, seen as humanactivity, is a powerful tool to achieve both of these goals (Skovsmose, 1994). When students use mathematics to explore, understand, and respond to social injustices they experience or care about, students learn not only the power of mathematics for social change, but also that they are actors on the world with the power to transform inequities and create social change. We want students to recognize that their mathematical power can improve the conditions of both their own lives and the lives of others. CONCLUSION We believe building instruction from students' lived experience is paramount for developing the whole, mathematically proficient student. One teacher may dem- onstrate an algorithm on the board and require students to repeat the process. Another teacher may implement an inquiry lesson, then have students share their solution pathways. Both of these situations teach mathematics with a specific goal in mind. The first teacher likely has a focus on procedural fluency intended to help students be successful on standardized testing, The second teacher likely has a focus on teaching mathematics for increasing students' problem-solving ability. Both of these classroom lesson analogies exemplify teaching mathematics with good intentions, but the teacher goals are different. Similarly, mathematics teachers must consider their goal as educators in a society that promotes justice by and for its citizens. Such a society requires informed and educated officials and citizens who can sift through rhetoric using logic and truth to guide policy, voting, and persuasion. A goal as a mathematics teacher teaching in a society governed by its people should be to engage students in critical inquiry about the world and potential injustices surrounding them, pushing students to imagine and create a world with justice, fairness, and equality. Providing students with opportunities to construct, revise, add to, and share the story with others, including the next generation, helps empower them fo be active agents of change to improve justice in the world, Similarly, we believe the same is true for mathematics teachers. I never thought about the importance of empowering my students to change their world. Now, having experienced the impact of a social justice teach- ing demonstration, I am constantly looking for ideas lo incorporate social justice topics that affect my students into my mathematics lessons. . . . I would suggest that teacher educators require students to not only experi- ence a social justice lesson within their program of study, but also design their own to use in their future classrooms. ~Dacia Irvin, Baker Middle School, Muscogee County, GA, Teacher of the Year (2019) Dacia's comment shows how teaching a social justice lesson in the classroom impacted her view of teaching mathematics in a society that promotes justice for each and every person. She noted how her teaching empowered students to be active agents of change. She identified the need and desire to connect mathematics and social justice concerns. It is evident that her experience teaching mathemat- ics for social justice changed her view of what mathematics may be used for by teachers and students alike. As both students and teachers experience new ideas teaching mathematics for social justice, they begin to develop an orientation that can promote a more just and equitable society. We are excited to share lessons contributed by educators across the United States that demonstrate their efforts to teach mathematics for social justice, and to achieve the four goals we've identified here. As teachers better understand how students learn mathematics, recognizing the importance of meaningful context and drawing upon students' cultural assets, it is an opportune moment to draw upon the generative themes they learn from their students to engage the students in mathematically rich activities and explore, understand, and respond to the social injustices they care about. It is an opportune time for mathematics teachers to reshape not only how they 'teach mathematics but how they use what they teach as a tool to empower their students to be agents of change in their society and their own lives. To put it in Dacia's terms, it is time to empower \"students to change the world.\" REFLECTION AND ACTION 1. Visit a colleague and initiate a conversation about why they became a teacher. Does the conversation draw on any of these lenses? + Build an informed society. + Connect mathematics with students' cultural and community histories. + Empower students to confront and solve real-world challenges they face. + Help students learn to use mathematics as a tool for social change

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts