Question: please read chapter and answer the following questions. All answers must be typed. thank you, will give thumbs up. 1. What kind of structure, controls,

please read chapter and answer the following questions. All answers must be typed. thank you, will give thumbs up.

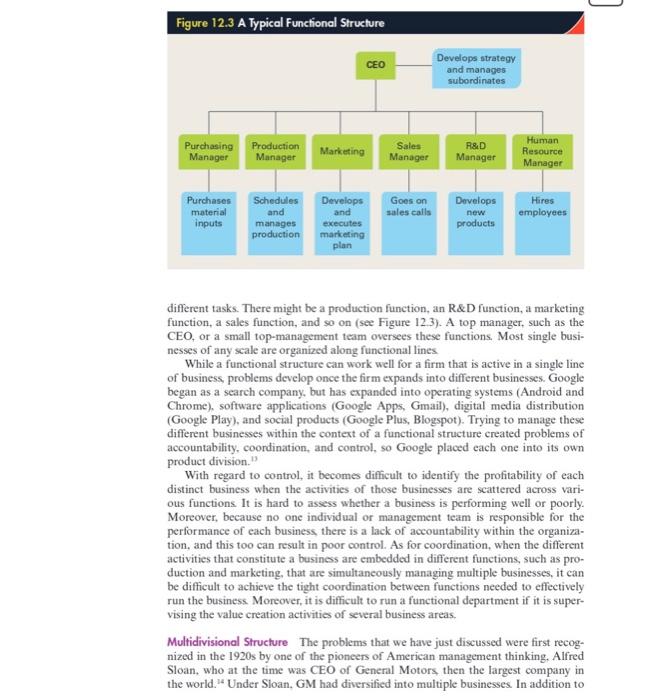

1. What kind of structure, controls, and culture would you be likely to find in (a) a small manufacturing company, (b) a chain store, (c) a high-tech company, (d) a Big Four accounting firm?

2. Discuss why the orgnaization's architecture is central for sucessfully implementing strategy.

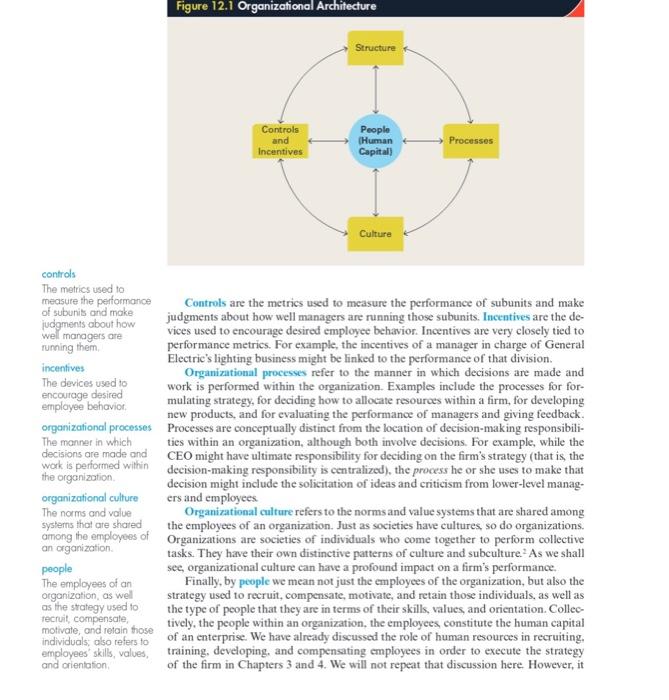

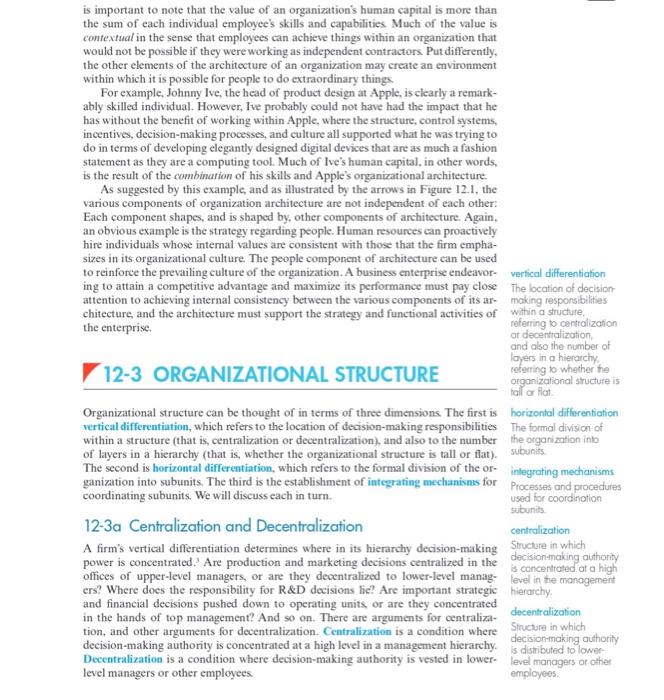

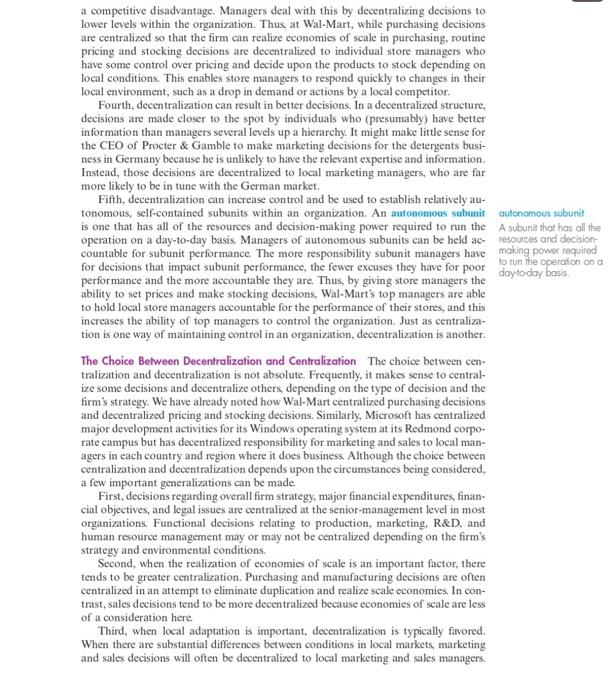

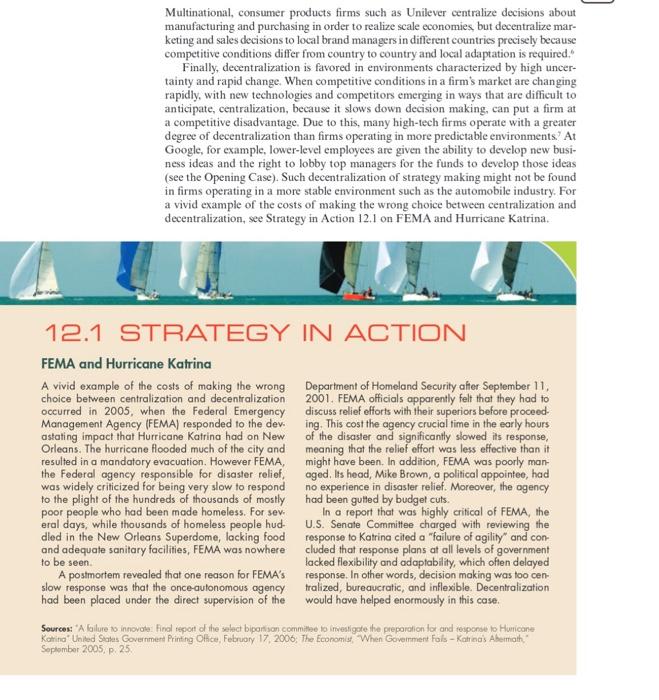

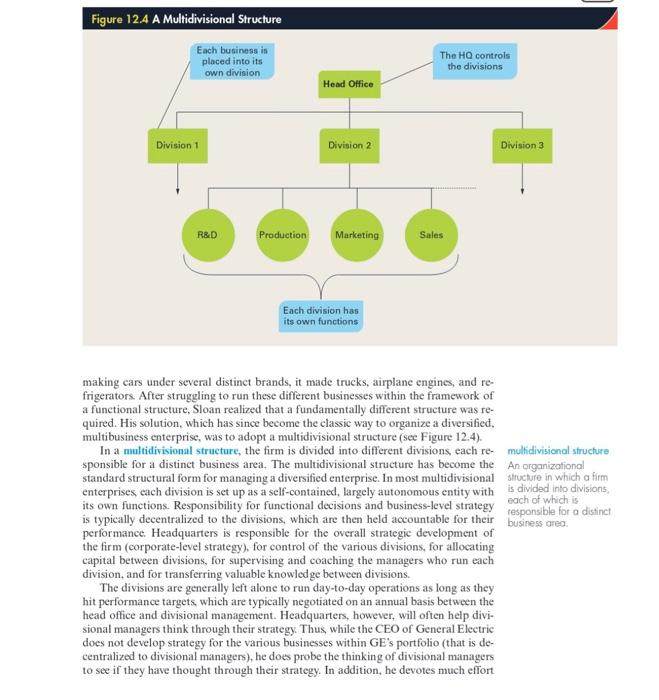

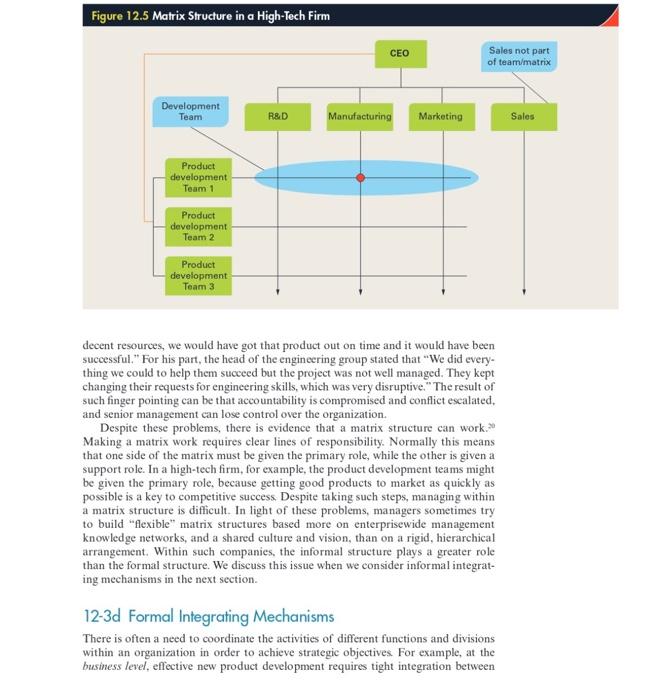

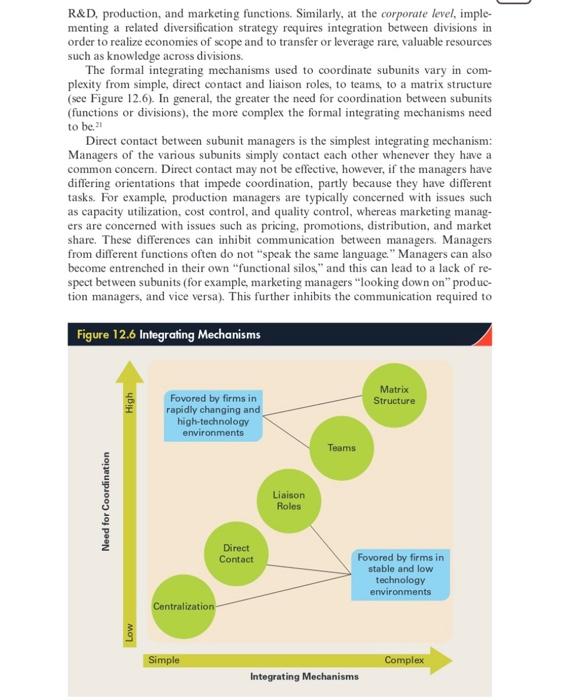

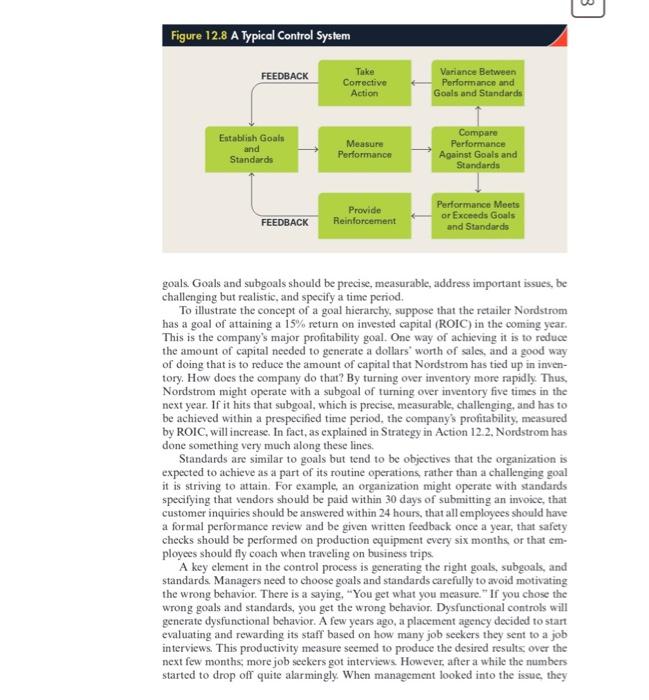

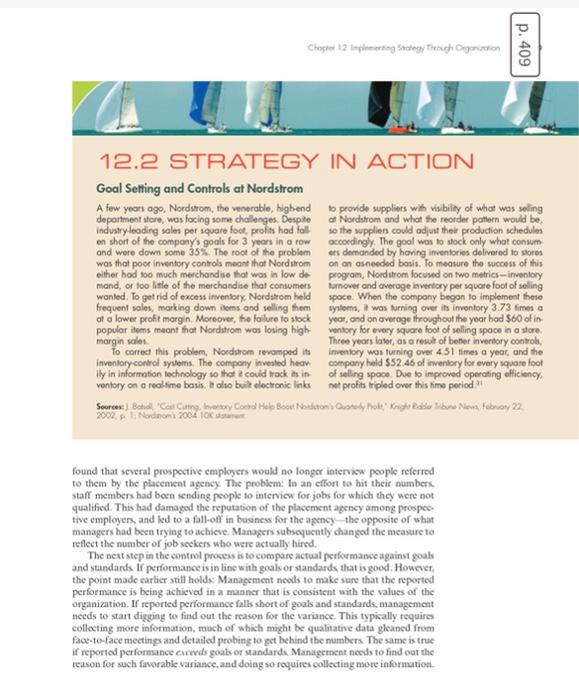

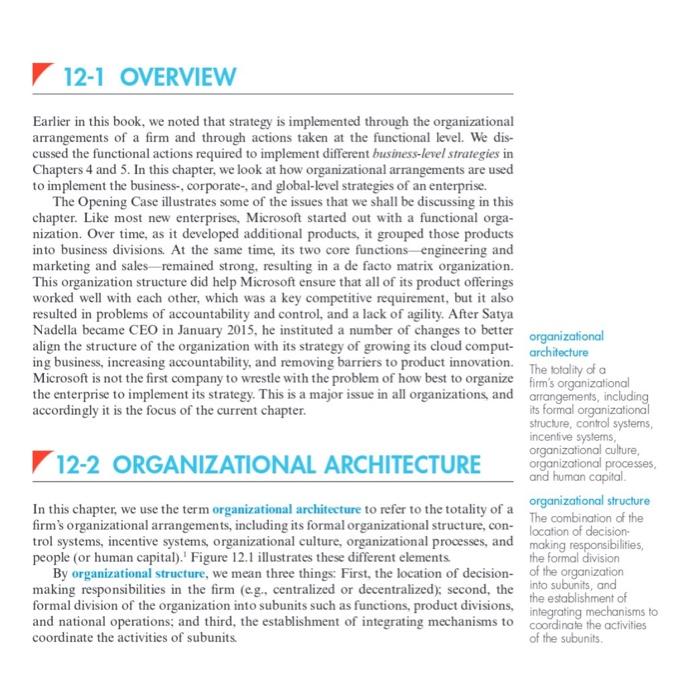

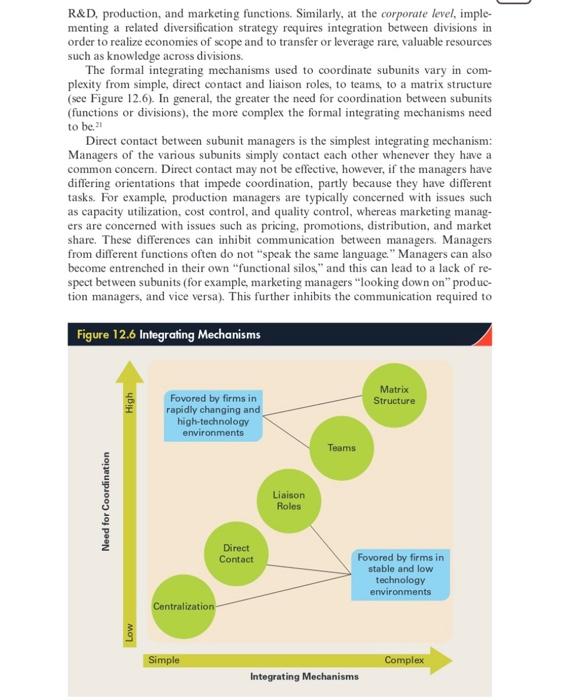

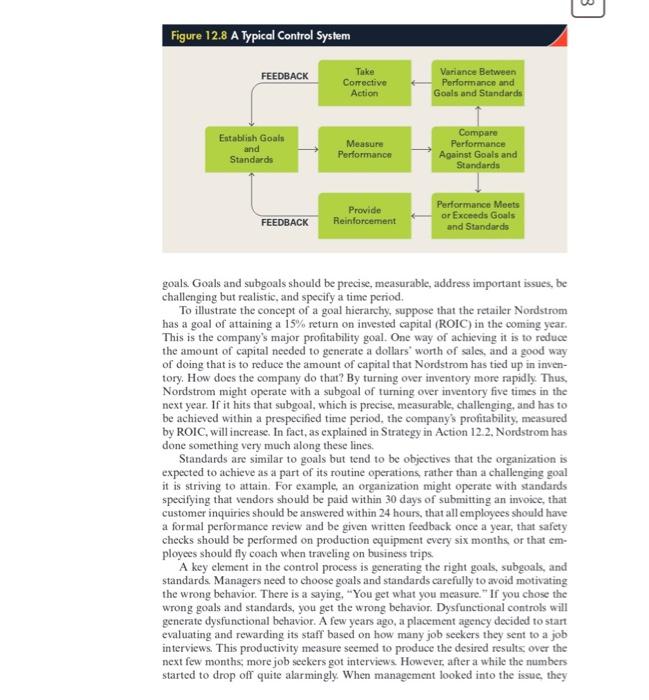

12-1 OVERVIEW Earlier in this book, we noted that strategy is implemented through the organizational arrangements of a firm and through actions taken at the functional level. We dis- cussed the functional actions required to implement different business-level strategies in Chapters 4 and 5. In this chapter, we look at how organizational arrangements are used to implement the business-, corporate-, and global-level strategies of an enterprise. The Opening Case illustrates some of the issues that we shall be discussing in this chapter. Like most new enterprises, Microsoft started out with a functional orga- nization. Over time, as it developed additional products, it grouped those products into business divisions. At the same time, its two core functions engineering and marketing and sales remained strong, resulting in a de facto matrix organization. This organization structure did help Microsoft ensure that all of its product offerings worked well with each other, which was a key competitive requirement, but it also resulted in problems of accountability and control, and a lack of agility. After Satya Nadella became CEO in January 2015, he instituted a number of changes to better align the structure of the organization with its strategy of growing its cloud comput- ing business, increasing accountability, and removing barriers to product innovation. Microsoft is not the first company to wrestle with the problem of how best to organize the enterprise to implement its strategy. This is a major issue in all organizations, and accordingly it is the focus of the current chapter. 12-2 ORGANIZATIONAL ARCHITECTURE In this chapter, we use the term organizational architecture to refer to the totality of a firm's organizational arrangements, including its formal organizational structure, con- trol systems, incentive systems, organizational culture, organizational processes, and people (or human capital). Figure 12.1 illustrates these different elements. By organizational structure, we mean three things: First, the location of decision making responsibilities in the firm (e.g., centralized or decentralized); second, the formal division of the organization into subunits such as functions, product divisions, and national operations; and third, the establishment of integrating mechanisms to coordinate the activities of subunits. organizational architecture The totality of a firm's organizational arrangements, including its formal organizational structure, control systems, incentive systems, organizational culture, organizational processes, and human capital. organizational structure The combination of the location of decision- making responsibilities, the formal division of the organization into subunits, and the establishment of integrating mechanisms to coordinate the activities of the subunits. Figure 12.1 Organizational Architecture Structure People Controls and Incentives Processes (Human Capital) Culture controls The metrics used to measure the performance of subunits and make judgments about how well managers are running them. Controls are the metrics used to measure the performance of subunits and make judgments about how well managers are running those subunits. Incentives are the de- vices used to encourage desired employee behavior. Incentives are very closely tied to performance metrics. For example, the incentives of a manager in charge of General Electric's lighting business might be linked to the performance of that division. incentives The devices used to encourage desired employee behavior. organizational processes The manner in which decisions are made and Organizational processes refer to the manner in which decisions are made and work is performed within the organization. Examples include the processes for for- mulating strategy, for deciding how to allocate resources within a firm, for developing new products, and for evaluating the performance of managers and giving feedback. Processes are conceptually distinct from the location of decision-making responsibili- ties within an organization, although both involve decisions. For example, while the CEO might have ultimate responsibility for deciding on the firm's strategy (that is, the decision-making responsibility is centralized), the process he or she uses to make that decision might include the solicitation of ideas and criticism from lower-level manag- ers and employees. work is performed within the organization. organizational culture The norms and value systems that are shared among the employees of an organization. Organizational culture refers to the norms and value systems that are shared among the employees of an organization. Just as societies have cultures, so do organizations. Organizations are societies of individuals who come together to perform collective tasks. They have their own distinctive patterns of culture and subculture. As we shall see, organizational culture can have a profound impact on a firm's performance. people The employees of an organization, as well as the strategy used to recruit, Finally, by people we mean not just the employees of the organization, but also the strategy used to recruit, compensate, motivate, and retain those individuals, as well as the type of people that they are in terms of their skills, values, and orientation. Collec- motivate, and retain those tively, the people within an organization, the employees, constitute the human capital of an enterprise. We have already discussed the role of human resources in recruiting, employees' skills, values, training, developing, and compensating employees in order to execute the strategy of the firm in Chapters 3 and 4. We will not repeat that discussion here. However, it individuals; also refers to and orientation, is important to note that the value of an organization's human capital is more than the sum of each individual employee's skills and capabilities. Much of the value is contextual in the sense that employees can achieve things within an organization that would not be possible if they were working as independent contractors. Put differently. the other elements of the architecture of an organization may create an environment within which it is possible for people to do extraordinary things. For example, Johnny Ive, the head of product design at Apple, is clearly a remark- ably skilled individual. However, Ive probably could not have had the impact that he has without the benefit of working within Apple, where the structure, control systems, incentives, decision-making processes, and culture all supported what he was trying to do in terms of developing elegantly designed digital devices that are as much a fashion statement as they are a computing tool. Much of Ive's human capital, in other words, is the result of the combination of his skills and Apple's organizational architecture. As suggested by this example, and as illustrated by the arrows in Figure 12.1, the various components of organization architecture are not independent of each other: Each component shapes, and is shaped by, other components of architecture. Again, an obvious example is the strategy regarding people. Human resources can proactively hire individuals whose internal values are consistent with those that the firm empha- sizes in its organizational culture. The people component of architecture can be used to reinforce the prevailing culture of the organization. A business enterprise endeavor- ing to attain a competitive advantage and maximize its performance must pay close attention to achieving internal consistency between the various components of its ar chitecture, and the architecture must support the strategy and functional activities of the enterprise. vertical differentiation The location of decision making responsibilities within a structure, referring to centralization or decentralization, and also the number of layers in a hierarchy, referring to whether the organizational structure is tall or flat. 12-3 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE Organizational structure can be thought of in terms of three dimensions. The first is vertical differentiation, which refers to the location of decision-making responsibilities within a structure (that is, centralization or decentralization), and also to the number of layers in a hierarchy (that is, whether the organizational structure is tall or flat). The second is horizontal differentiation, which refers to the formal division of the or- ganization into subunits. The third is the establishment of integrating mechanisms for coordinating subunits. We will discuss each in turn. horizontal differentiation The formal division of the organization into subunits. integrating mechanisms Processes and procedures used for coordination subunits 12-3a Centralization and Decentralization centralization A firm's vertical differentiation determines where in its hierarchy decision-making Structure in which power is concentrated. Are production and marketing decisions centralized in the is concentrated at a high decision-making authority offices of upper-level managers, or are they decentralized to lower-level manag-level in the management ers? Where does the responsibility for R&D decisions lie? Are important strategic hierarchy. and financial decisions pushed down to operating units, or are they concentrated in the hands of top management? And so on. There are arguments for centraliza- tion, and other arguments for decentralization. Centralization is a condition where decision-making authority is concentrated at a high level in a management hierarchy. Decentralization is a condition where decision-making authority is vested in lower level managers or other employees. decentralization Structure in which decision-making authority is distributed to lower level managers or other employees. Arguments for Centralization There are four main arguments for centralization. First, it can facilitate coordination. For example, consider a firm that that has a compo- nent manufacturing operation in California and a final assembly operation in Seattle. The activities of these two operations need to be coordinated to ensure a smooth flow of products from the component operation to the assembly operation. This might be achieved by centralizing production scheduling at the firm's head office. Second, centralization can help ensure that decisions are consistent with organi- zational objectives. When decisions are decentralized to lower-level managers, those managers may make decisions at variance with top management's goals. Centraliza- tion of important decisions minimizes the chance of this occurring. Major strategic decisions, for example, are often centralized in an effort to make sure that the entire organization is pulling in the same direction. In this sense, centralization is a way of controlling the organization. Third, centralization can avoid the duplication of activities that occurs when simi- lar activities are carried on by various subunits within the organization. For example, many firms centralize their R&D functions at one or two locations to ensure that R&D work is not duplicated. Similarly, production activities may be centralized at key locations to eliminate duplication, attain economies of scale, and lower costs. The same may also be true of purchasing decisions. Wal-Mart, for example, has centralized all purchasing decisions at its headquarters in Arkansas. By wielding its enormous bargaining power, purchasing managers at the head office can drive down the costs that Wal-Mart pays for the goods it sells in its stores. It then passes on those savings to consumers in the form of lower prices, which enables the company to grow its market share and profits. Fourth, by concentrating power and authority in one individual or a management team, centralization can give top-level managers the means to bring about needed ma- jor organizational changes. Often times, firms seeking to transform their organizations centralize power and authority in a key individual (or group), who then sets the new strategic direction for the firm and redraw organizational architecture. Once the new strategy and architecture have been decided upon, however, greater decentralization of decision making normally follows. Put differently, the temporary centralization of decision-making power is often an important step in organizational change. Arguments for Decentralization There are five main arguments for decentralization. First, top management can become overburdened when decision-making authority is centralized. Centralization increases the amount of information that senior manag- ers have to process, and this can result in information overload and poor decision making. Decentralization gives top management time to focus on critical issues by delegating more routine issues to lower-level managers and reducing the amount of information top managers have to process. Second, motivational research favors decentralization. Behavioral scientists have long argued that people are willing to give more to their jobs when they have a greater degree of individual freedom and control over their work. The idea behind employee empowerment is that if you give employees more responsibility for their jobs, they will work harder, increasing productivity and reducing costs Third, decentralization permits greater flexibility more rapid response to envi- ronmental changes. In a centralized firm, the need to refer decisions up the hierarchy for approval can significantly impede the speed of decision making and inhibit the ability of the firm to adapt to rapid environmental changes. This can put the firm at a competitive disadvantage. Managers deal with this by decentralizing decisions to lower levels within the organization. Thus, at Wal-Mart, while purchasing decisions are centralized so that the firm can realize economies of scale in purchasing, routine pricing and stocking decisions are decentralized to individual store managers who have some control over pricing and decide upon the products to stock depending on local conditions. This enables store managers to respond quickly to changes in their local environment, such as a drop in demand or actions by a local competitor. Fourth, decentralization can result in better decisions. In a decentralized structure, decisions are made closer to the spot by individuals who (presumably) have better information than managers several levels up a hierarchy. It might make little sense for the CEO of Procter & Gamble to make marketing decisions for the detergents busi- ness in Germany because he is unlikely to have the relevant expertise and information. Instead, those decisions are decentralized to local marketing managers, who are far more likely to be in tune with the German market. autonomous subunit A subunit that has all the resources and decision- making power required to run the operation on a Fifth, decentralization can increase control and be used to establish relatively au- tonomous, self-contained subunits within an organization. An autonomous subunit is one that has all of the resources and decision-making power required to run the operation on a day-to-day basis Managers of autonomous subunits can be held ac- countable for subunit performance. The more responsibility subunit managers have for decisions that impact subunit performance, the fewer excuses they have for poor day-to-day basis. performance and the more accountable they are. Thus, by giving store managers the ability to set prices and make stocking decisions, Wal-Mart's top managers are able to hold local store managers accountable for the performance of their stores, and this increases the ability of top managers to control the organization. Just as centraliza- tion is one way of maintaining control in an organization, decentralization is another. The Choice Between Decentralization and Centralization The choice between cen- tralization and decentralization is not absolute. Frequently, it makes sense to central- ize some decisions and decentralize others, depending on the type of decision and the firm's strategy. We have already noted how Wal-Mart centralized purchasing decisions and decentralized pricing and stocking decisions. Similarly, Microsoft has centralized major development activities for its Windows operating system at its Redmond corpo- rate campus but has decentralized responsibility for marketing and sales to local man- agers in each country and region where it does business. Although the choice between centralization and decentralization depends upon the circumstances being considered, a few important generalizations can be made. First, decisions regarding overall firm strategy, major financial expenditures, finan- cial objectives, and legal issues are centralized at the senior-management level in most organizations. Functional decisions relating to production, marketing, R&D, and human resource management may or may not be centralized depending on the firm's strategy and environmental conditions. Second, when the realization of economies of scale is an important factor, there tends to be greater centralization. Purchasing and manufacturing decisions are often centralized in an attempt to eliminate duplication and realize scale economies. In con- trast, sales decisions tend to be more decentralized because economies of scale are less of a consideration here. Third, when local adaptation is important, decentralization is typically favored. When there are substantial differences between conditions in local markets, marketing and sales decisions will often be decentralized to local marketing and sales managers. Multinational, consumer products firms such as Unilever centralize decisions about manufacturing and purchasing in order to realize scale economies, but decentralize mar- keting and sales decisions to local brand managers in different countries precisely because competitive conditions differ from country to country and local adaptation is required." Finally, decentralization is favored in environments characterized by high uncer- tainty and rapid change. When competitive conditions in a firm's market are changing rapidly, with new technologies and competitors emerging in ways that are difficult to anticipate, centralization, because it slows down decision making, can put a firm at a competitive disadvantage. Due to this, many high-tech firms operate with a greater degree of decentralization than firms operating in more predictable environments. At Google, for example, lower-level employees are given the ability to develop new busi- ness ideas and the right to lobby top managers for the funds to develop those ideas (see the Opening Case). Such decentralization of strategy making might not be found in firms operating in a more stable environment such as the automobile industry. For a vivid example of the costs of making the wrong choice between centralization and decentralization, see Strategy in Action 12.1 on FEMA and Hurricane Katrina. 12.1 FEMA and Hurricane Katrina A vivid example of the costs of making the wrong choice between centralization and decentralization occurred in 2005, when the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) responded to the dev astating impact that Hurricane Katrina had on New Orleans. The hurricane flooded much of the city and resulted in a mandatory evacuation. However FEMA, the Federal agency responsible for disaster relief, was widely criticized for being very slow to respond to the plight of the hundreds of thousands of mostly poor people who had been made homeless. For sev. eral days, while thousands of homeless people hud- died in the New Orleans Superdome, lacking food and adequate sanitary facilities, FEMA was nowhere to be seen. Department of Homeland Security after September 11, 2001. FEMA officials apparently felt that they had to discuss relief efforts with their superiors before proceed ing. This cost the agency crucial time in the early hours of the disaster and significantly slowed its response, meaning that the relief effort was less effective than it might have been. In addition, FEMA was poorly man- aged. Its head, Mike Brown, a political appointee, had no experience in disaster relief. Moreover, the agency had been gutted by budget cuts. In a report that was highly critical of FEMA, the U.S. Senate Committee charged with reviewing the response to Katrina cited a "failure of agility and con- cluded that response plans at all levels of government lacked flexibility and adaptability, which often delayed response. In other words, decision making was too cen- tralized, bureaucratic, and inflexible. Decentralization would have helped enormously in this case. A postmortem revealed that one reason for FEMA's slow response was that the once-autonomous agency had been placed under the direct supervision of the Sources: "A failure to innovate: Final report of the select bipartisan committee to investigate the preparation for and response to Hurricane Katrina United States Government Printing Office, February 17, 2006; The Economist, When Government Fals-Katrina's Abermath, September 2005, p. 25. STRATEGY IN ACTION 12-3b Tall Versus Flat Hierarchies A second aspect of vertical differentiation refers to the number of levels in an or- ganization hierarchy. Tall hierarchies have many layers of management, while flat hierarchies have very few layers (see Figure 12.2). Most firms start out small, often with only one or at most two layers in the hierarchy. As they grow, management finds that there is a limit to the amount of information they can process and the control they can exert over day-to-day operations. To avoid being stretched too thin and los- ing control, they tend to add another layer to the management hierarchy, hiring more managers and delegating some decision-making authority to them. In other words, as an organization gets larger it tends to become taller. In addition, growing organiza- tions often undertake more activities, expanding their product line, diversifying into adjacent activities, vertically integrating, or expanding into new regional or national markets. This too creates problems of coordination and control, and once again the organization's response often is to add another management layer. Adding levels in the hierarchy is a problem that mounts when managers have too much work to do. The number of layers added is also partly determined by the span of control that managers can effectively handle. Span of Control The term span of control refers to the number of direct reports that a manager has. At one time, it was thought that the optimal span of control was six subordinates. The argument was that, if a manager was responsible for more than six subordinates, he or she would soon lose track of what was going on and control loss would occur. Now we recognize that the relationship is not this simple. The number of direct reports a manger can handle depends upon (1) the nature of the work being supervised, (2) the extent to which the performance of subordinates is visible, and (3) the extent of decentralization within the organization. Generally, if the work being performed by subordinates is routine, their performance is visible and easy to measure. and they are empowered to make many decisions and need not refer up the hierarchy Figure 12.2 Tall Versus Flat Hierarchies A tall hierarchy has many layers and narrow spans of control A flat hierarchy has few layers and wide spans of control Tall Hierarchy Flat Hierarchy ] tall hierarchies An organizational structure with many layers of management. flat hierarchies An organizational structure with very few layers of management. span of control The number of a manager's direct reports. influence costs The loss of efficiency that arises from deliberate information distortions for personal gain within an organization. for approval or consultation, managers can operate with a wide span of control. How wide is the subject of debate, but it does seem as if managers can effectively handle as many as 20 direct reports if the circumstances are right. In sum, as organizations grow and undertake more activities, the management hi- erarchy tends to be come taller, but how tall depends upon the span of control that is feasible, and that in turn depends upon the nature of the work being performed, the visibility of subordinate performance, and the extent of decentralization within the or- ganization. It is important to note that managers can influence the visibility of subunit performance and the extent of decentralization through organization design, thereby limiting the impact of organization size and diversity on the size of a management hierarchy. This is significant, because we know that while adding layers to an organiza- tion can reduce the workload of higher-level managers and attenuate control loss, tall hierarchies have their own problems. Problems in Tall Hierarchies Several problems can occur in tall hierarchies that may result in lower organizational efficiency and effectiveness. First, there is a tendency for information to get accidentally distorted as it passes through layers in a hierar- chy. The phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has played the game "telephone," in which players sit in a circle and each whispers a message to the person sitting next to them, who then whispers the message to the next person, and so on around the room. Often, by the time the message has been transmitted through all the players, it has become distorted and its meaning has changed (this can have amusing consequences, which of course is the point of the game). Human beings are not adept at transmitting information: we tend to embellish or omit data. In a management context, if criti- cal information has to pass through many layers in a tall hierarchy before it reaches critical decision makers, it may well get distorted in the process, resulting in a message that differs from the one originally sent. As a result, decisions may be made based on inaccurate information, and poor performance may result. In addition to the accidental distortion of information as it travels through a management hierarchy, there is also the problem of deliberate distortion by midlevel managers trying to curry favor with their superiors or pursue a personal agenda. For example, the manager of a division might suppress negative information while exag- gerating positive information in an attempt to "window dress" the performance of the unit under his control to higher-level managers and win their approval. By doing so he may gain access to more resources, earn performance bonuses, or avoid sanc- tions for poor performance. All things being equal, the more layers in a hierarchy, the more opportunities exist for people to deliberately distort information. To the extent that information is distorted, once again it implies that senior managers will be mak- ing important decisions on the basis of inaccurate information, which can result in poor performance. Economists refer to the loss of efficiency that arises from deliber- ate information distortions for personal gain within an organization as influence costs, which they argue can be a major source of low efficiency. An interesting case of information distortion in a hierarchy concerned the quality of prewar intelligence information on weapons of mass destruction in Iraq prior to the 2003 invasion by the United States and allied forces. The information on biological weapons that was used to help justify the invasion of Iraq was derived from a single Iraqi defector, code named "Curveball," who was an alcoholic and, in the view of the one person who had interviewed him, a Pentagon analyst, "utterly useless as a source." However, higher-level personnel in the intelligence community took the information provided by Curveball, stripped out the reservations expressed by the Pentagon ana- lyst, and passed it on as high-quality intelligence to U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell, who included the information in a speech he made to the United Nations to justify the war. Powell was apparently unaware of the highly questionable nature of the data. He stated later that had he been aware of this he would not have included it in his speech. Apparently, gatekeepers who stood between Powell and the Pentagon analyst deliberately distorted the information, presumably to further their own agenda or the agenda of other parties whose favor they were trying to curry. A third problem with tall hierarchies is that they are expensive. The salaries and benefits of multiple layers of midlevel managers can add up to significant overhead, which can increase the cost structure of the firm. Unless there is a commensurate ben- efit, a tall hierarchy can put a firm at a competitive disadvantage. A final problem concerns the inherent inertia associated with a tall hierarchy. Organizations are inherently inert that is, they are difficult to change. One cause of inertia in an organization is that, in order to protect their turf, and perhaps their jobs, managers often argue for the maintenance of the status quo. In tall hierarchies there is more turf, more centers of power and influence, and more voices arguing against change. Thus, tall hierarchies tend to be slow to change. Delayering-Reducing the Size of a Hierarchy Many firms attempt to limit the size of the management hierarchy. Delayering to reduce the number of levels in a manage- ment hierarchy has become a standard component of many attempts to boost a firm's performance." Delayering is based on the assumption that when times are good, many firms tend to expand their management hierarchies beyond the point at which it is effi- cient to do so. However, the bureaucratic inefficiencies associated with a tall hierarchy become evident when the competitive environment becomes tougher, at which time managers seek to delayer the organization. Delayering, and simultaneously widening spans of control, is also seen as a way of enforcing greater decentralization within an organization and reaping the associated efficiency gains. The process of delayering was a standard feature of Jack Welch's tenure at General Electric, during which time he laid off 150,000 people and reduced the number of layers in the hierarchy from nine to five, while simultaneously growing GE's profits and revenues. Welch believed that GE had become too top heavy during the tenure of his successors. A key element of his strategy was to transform General Electric into a leaner, faster-moving organization, which required delayering. Welch himself had a wide span of control, with some 20 subordinates reporting directly to him, including the heads of GE's 15 top businesses. Similarly, Jeffery Immelt, the head of GE's med- ical-systems business under Welch, had 21 direct reports (Immelt eventually replaced Welch as CEO),2 12-3c Structural Forms Most firms begin with no formal structure and are run by a single entrepreneur or a small team of individuals. As they grow, the demands of management become too great for one individual or a small team to handle. At this point, the organization is split into functions that represent different aspects of the firm's value chain (see Chapter 3). Functional Structure In a functional structure, the structure of the organization fol- lows the obvious division of labor within the firm with different functions focusing on delayering The process of reducing the number of levels in a management hierarchy. functional structure An organizational structure built upon the division of labor within the firm, with different functions focusing on different tasks. Figure 12.3 A Typical Functional Structure CEO Develops strategy and manages subordinates Production Purchasing Manager Sales Manager Marketing Human Resource R&D Manager Manager Manager Purchases Schedules Goes on Develops Hires and sales calls new employees material inputs Develops and executes marketing plan manages production products different tasks. There might be a production function, an R&D function, a marketing function, a sales function, and so on (see Figure 12.3). A top manager, such as the CEO, or a small top-management team oversees these functions. Most single busi- nesses of any scale are organized along functional lines While a functional structure can work well for a firm that is active in a single line of business, problems develop once the firm expands into different businesses. Google began as a search company, but has expanded into operating systems (Android and Chrome), software applications (Google Apps, Gmail), digital media distribution (Google Play), and social products (Google Plus, Blogspot). Trying to manage these different businesses within the context of a functional structure created problems of accountability, coordination, and control, so Google placed each one into its own product division." With regard to control, it becomes difficult to identify the profitability of each distinct business when the activities of those businesses are scattered across vari- ous functions. It is hard to assess whether a business is performing well or poorly. Moreover, because no one individual or management team is responsible for the performance of each business, there is a lack of accountability within the organiza- tion, and this too can result in poor control. As for coordination, when the different activities that constitute a business are embedded in different functions, such as pro- duction and marketing, that are simultaneously managing multiple businesses, it can be difficult to achieve the tight coordination between functions needed to effectively run the business. Moreover, it is difficult to run a functional department if it is super- vising the value creation activities of several business areas. Multidivisional Structure The problems that we have just discussed were first recog- nized in the 1920s by one of the pioneers of American management thinking, Alfred Sloan, who at the time was CEO of General Motors, then the largest company in the world." Under Sloan, GM had diversified into multiple businesses. In addition to Figure 12.4 A Multidivisional Structure Each business is placed into its own division Division 1 Production Head Office Division 2 R&D Sales Each division has its own functions making cars under several distinct brands, it made trucks, airplane engines, and re- frigerators. After struggling to run these different businesses within the framework of a functional structure, Sloan realized that a fundamentally different structure was re- quired. His solution, which has since become the classic way to organize a diversified, multibusiness enterprise, was to adopt a multidivisional structure (see Figure 12.4). In a multidivisional structure, the firm is divided into different divisions, each re- sponsible for a distinct business area. The multidivisional structure has become the standard structural form for managing a diversified enterprise. In most multidivisional enterprises, each division is set up as a self-contained, largely autonomous entity with its own functions. Responsibility for functional decisions and business-level strategy is typically decentralized to the divisions, which are then held accountable for their performance. Headquarters is responsible for the overall strategic development of the firm (corporate-level strategy), for control of the various divisions, for allocating capital between divisions, for supervising and coaching the managers who run each division, and for transferring valuable knowledge between divisions. The divisions are generally left alone to run day-to-day operations as long as they hit performance targets, which are typically negotiated on an annual basis between the head office and divisional management. Headquarters, however, will often help divi- sional managers think through their strategy. Thus, while the CEO of General Electric does not develop strategy for the various businesses within GE's portfolio (that is de- centralized to divisional managers), he does probe the thinking of divisional managers to see if they have thought through their strategy. In addition, he devotes much effort The HQ controls the divisions Marketing Division 3 multidivisional structure An organizational structure in which a firm is divided into divisions, each of which is responsible for a distinct business area. matrix structure An organizational structure in which managers try to achieve tight coordination between functions, particularly R&D, production, and marketing to getting managers to share best practices across divisions, and to the formulation and implementation of strategies that span multiple businesses One great virtue claimed for the multidivisional structure is that it creates an inter- nal environment where divisional managers focus on efficiency. Because each division is a self-contained entity, its performance is highly visible. The high level of respon- sibility and accountability implies that divisional managers have few alibis for poor performance. This motivates them to focus on improving efficiency. Base pay, bonuses, and promotional opportunities for divisional managers can be tied to how well the division does Capital is also allocated by top management between the competing di- visions depending upon how effectively top management thinks the division managers can invest that capital. The desire to get access to capital to grow their businesses, and to gain pay increases and bonuses, creates further incentives for divisional managers to focus on improving the competitive position of the businesses under their control. On the other hand, too much pressure from the head office on divisional manag- ers to improve performance can result in some of the worst practices of management. These can include cutting necessary investments in plant, equipment, and R&D to boost short-term performance, even though such action can damage the long-term competitive position of the enterprise." To guard against this possibility, top manag- ers need to develop a good understanding of each division, set performance goals that are attainable, and acquire personnel who can regularly audit the accounts and opera- tions of divisions to ensure that they are not being managed for short-term results or in a way that destroys their long-term competitiveness. Matrix Structure High-technology firms based in rapidly changing environments sometimes adopt a matrix structure in which they try to achieve tight coordination between functions, particularly R&D, production, and marketing. As we saw in the Opening Case, for a long time Microsoft operated with a de facto matrix structure. Tight coordination is required so that R&D designs products that (a) can be manu- factured efficiently, and (b) are designed with customer needs in mind-both of which increase the probability of successful product commercialization (see Chapter 4). Tight coordination between R&D, manufacturing, and marketing has also been shown to result in a quicker product development effort, which can enable a firm to gain an advantage over its rivals." As illustrated in Figure 12.5, in such an organization an employee might belong to two subunits within the firm. For example, a manager might be a member of the manufacturing function and a product development team. A matrix structure looks nice on paper, but the reality can be very different. Unless this structure is managed very carefully it may not work well." In practice, the matrix can be clumsy and bureaucratic. It can require so many meetings that it is difficult to get any work done. The dual-hierarchy structure can lead to conflict and perpetual power struggles between the different sides of the hierarchy. In one high-tech firm, for example, the manufacturing manager was reluctant to staff a product development team with his best people because he felt that would distract them from their func- tional work. The result was that the product development team did not work as well it might have. To make matters worse, it can prove difficult to ascertain accountability in a matrix structure. When all critical decisions are the product of negotiation between different hierarchies, one side can always blame the other when things go wrong. As a manager in one high-tech matrix structure said to the author when reflecting on a failed prod- uct launch, "Had the engineering [R&D] group provided our development team with Figure 12.5 Matrix Structure in a High-Tech Firm Development Team R&D Sales not part of team/matrix Manufacturing Marketing Sales Product development. Team 1 Product development Team 2 Product development Team 3 decent resources, we would have got that product out on time and it would have been successful." For his part, the head of the engineering group stated that "We did every- thing we could to help them succeed but the project was not well managed. They kept changing their requests for engineering skills, which was very disruptive." The result of such finger pointing can be that accountability is compromised and conflict escalated, and senior management can lose control over the organization. Despite these problems, there is evidence that a matrix structure can work. Making a matrix work requires clear lines of responsibility. Normally this means that one side of the matrix must be given the primary role, while the other is given a support role. In a high-tech firm, for example, the product development teams might be given the primary role, because getting good products to market as quickly as possible is a key to competitive success. Despite taking such steps, managing within a matrix structure is difficult. In light of these problems, managers sometimes try to build "flexible" matrix structures based more on enterprisewide management knowledge networks, and a shared culture and vision, than on a rigid, hierarchical arrangement. Within such companies, the informal structure plays a greater role than the formal structure. We discuss this issue when we consider informal integrat- ing mechanisms in the next section. 12-3d Formal Integrating Mechanisms There is often a need to coordinate the activities of different functions and divisions within an organization in order to achieve strategic objectives. For example, at the business level, effective new product development requires tight integration between CEO R&D, production, and marketing functions. Similarly, at the corporate level, imple- menting a related diversification strategy requires integration between divisions in order to realize economies of scope and to transfer or leverage rare, valuable resources such as knowledge across divisions. The formal integrating mechanisms used to coordinate subunits vary in com- plexity from simple, direct contact and liaison roles, to teams, to a matrix structure (see Figure 12.6). In general, the greater the need for coordination between subunits (functions or divisions), the more complex the formal integrating mechanisms need to be." Direct contact between subunit managers is the simplest integrating mechanism: Managers of the various subunits simply contact each other whenever they have a common concern. Direct contact may not be effective, however, if the managers have differing orientations that impede coordination, partly because they have different tasks. For example, production managers are typically concerned with issues such as capacity utilization, cost control, and quality control, whereas marketing manag- ers are concerned with issues such as pricing, promotions, distribution, and market share. These differences can inhibit communication between managers. Managers from different functions often do not "speak the same language." Managers can also become entrenched in their own "functional silos," and this can lead to a lack of re- spect between subunits (for example, marketing managers "looking down on" produc- tion managers, and vice versa). This further inhibits the communication required to Figure 12.6 Integrating Mechanisms Matrix Structure Fovored by firms in rapidly changing and high-technology environments Need for Coordination High Low Direct Contact Centralization- Simple Liaison Roles Teams Fovored by firms in stable and low technology environments Complex Integrating Mechanisms achieve cooperation and coordination. For these reasons, direct contact is rarely suf- ficient to achieve coordination between subunits when the need for integration is high. Liaison roles are a bit more complex than direct contact. As the need for coordina- tion between subunits increases, integration can be improved by giving one individual in each subunit responsibility for coordinating with other subunits on a regular basis. Through these roles, the employees involved establish a permanent relationship, which helps attenuate the impediments to coordination discussed above. When the need for coordination is greater still, firms often use temporary or per- manent teams composed of individuals from the subunits that need to achieve coordi- nation. Teams are often used to coordinate product development efforts, but they can be useful when any aspect of operations or strategy requires the cooperation of two or more subunits. Product development teams are typically composed of personnel from R&D, production, and marketing. The resulting coordination aids the development of products that are tailored to consumer needs and can be produced at a reasonable cost (through design for manufacturing). When the need for integration is very high, firms may institute a matrix structure in which all roles are viewed as integrating roles. The structure is designed to facilitate maximum integration among subunits. However, as we have already noted, matrix structures can quickly become bogged down in a bureaucratic tangle that creates as many problems as it solves. If not well managed, matrix structures can become bu- reaucratic, inflexible, and characterized by conflict rather than the hoped-for coopera- tion. For such a structure to work, it needs to be somewhat flexible and be supported by informal integrating mechanisms. 12-3e Informal Integrating Mechanisms In attempting to alleviate or avoid the problems associated with formal integrating mechanisms in general, and matrix structures in particular, firms with a high need for integration have been experimenting with an informal integrating mechanism: knowl- edge networks that are supported by an organization culture that values teamwork and cross-unit cooperation." A knowledge network is a system for transmitting infor- mation within an organization that is based not on formal organizational structure but on informal contacts between managers within an enterprise." The great strength of such a network is that it can be used as a nonbureaucratic conduit for knowledge flow within an enterprise." For a network to exist, managers at different locations within the organization must be linked to each other, at least indirectly. For example, Figure 12.7 shows the simple network relationships between seven managers within a multinational firm. Managers A, B, and C all know each other personally, as do Man- agers D, E, and F. Although Manager B does not know Manager F personally, they are linked through common acquaintances (Managers C and D). Thus, Managers A through F are all part of the network; Manager G is not. Imagine Manager B, a marketing manager in Spain, needs to know the solution to a technical problem to better serve an important European customer. Manager F. an R&D manager in the United States, has the solution to Manager B's problem. Manager B mentions her problem to all of her contacts, including Manager C, and asks if they know of anyone who might be able to provide a solution. Manager Casks Manager D, who tells Manager F, who then calls Manager B with the solution. In this way, coordination is achieved informally through the network, rather than by formal integrating mechanisms such as teams or a matrix structure. J knowledge network A network for transmitting information within an organization that is based not on formal organization structure but on informal contacts between managers within an enterprise and on distributed-information systems. Figure 12.7 A Knowledge Network For such a network to function effectively, it must embrace as many managers as possible. For example, if Manager G had a problem similar to manager B's, he would not be able to utilize the informal network to find a solution; he would have to resort to more formal mechanisms. Establishing firmwide knowledge networks is difficult. Although network enthusiasts speak of networks as the "glue" that binds complex organizations together, it is far from clear how successful firms have been at building companywide networks. The techniques that have been used to establish knowledge networks include information systems, management development policies, and conferences. Firms are using their distributed computer and telecommunications information systems to provide the foundation for informal knowledge networks E-mail, video- conferencing, intranets, and web-based search engines make it much easier for man- agers scattered over the globe to get to know each other, identify contacts who might help to solve a particular problem, and publicize and share best practices within the organization. Wal-Mart, for example, uses its intranet system to communicate ideas about merchandizing strategy between stores located in different countries. Firms are also using their management development programs to build informal networks. Tactics include rotating managers through various subunits on a regular basis, so they build their own informal network, and using management education programs to bring managers of subunits together in a single location so they can be- come acquainted. In addition, some science-based firms use internal conferences as a way to establish contacts between people in different units of the organization. At 3M, regular, multidisciplinary conferences bring together scientists from different business units and get them talking to each other. Apart from the benefits of direct interaction in the conference setting, the idea is that once the conference is over, the scientists may continue to share ideas, and this will increase knowledge flows within the organization. 3M has many stories of product ideas that were the result of such knowledge flows, including the ubiquitous Post-it Notes, whose inventor, Art Fry, first learned about the adhesive that he would use on the product from a colleague working in another division of 3M, Spencer Silver, who had spent several years shopping his adhesive around 3M.27 Knowledge networks alone may not be sufficient to achieve coordination if subunit managers persist in pursuing subgoals that are at variance with firmwide goals. For a knowledge network to function properly and for a formal matrix structure to work as well-managers must share a strong commitment to the same goals. To appreciate the nature of the problem, consider again the case of Manager B and Manager F. As before, Manager F hears about Manager B's problem through the network. However, solving Manager B's problem would require Manager F to devote considerable time to the task. Insofar as this would divert Manager F away from his regular tasks and the pursuit of subgoals that differ from those of Manager Bhe may be unwilling to do it. Thus, Manager F may not call Manager B, and the informal network would fail to provide a solution to Manager B's problem. To eliminate this flaw, an organization's managers must adhere to a common set of norms and values that override differing subunit orientations In other words, the firm must have a strong organizational culture that promotes teamwork and coop- eration. When this is the case, a manager is willing and able to set aside the interests of his own subunit when doing so benefits the firm as a whole. If Manager B and Manager F are committed to the same organizational norms and value systems, and if these organizational norms and values place the interests of the firm as a whole above the interests of any individual subunit, Manager F should be willing to cooperate with Manager B on solving her subunit's problems. 12-4 ORGANIZATION CONTROLS AND INCENTIVES One critical management task is to control an organization's activities. Controls are an integral part of an enterprise's organizational architecture. They are necessary to en- sure that an organization is operating efficiently and effectively, and in a manner that is consistent with its intended strategy. Without adequate controls, control loss occurs and the organization's performance will suffer. control the process through which managers regulate the activities of individuals and units so that they are consistent with the goals and standards of the 12-4a Control Systems organization. goal Control can be viewed as the process through which managers regulate the activities of individuals and units so that they are consistent with the goals and standards of the organization. A goal is a desired future state that an organization attempts A desired future state that to realize. A standard is a performance requirement that the organization is meant on organization attempts to attain on an ongoing basis. Managers can regulate the activities of individuals to realize. and units in several different ways to assure that they are consistent with a firm's goals and standards. Before considering these, we need to review the workings of a typical control system. As illustrated in Figure 12.8, this system has five main elements; establishing goals and standards, measuring performance, comparing per- formance against goals and standards, taking corrective action, and/or providing standard that the organization is A performance requirement meant to attain on an ongoing basis. reinforcement." subgoal An objective, the Most organizations operate with a hierarchy of goals. In the case of a business enterprise, the major goals at the top of the hierarchy are normally expressed in terms of profitability and profit growth. These major goals are typically translated into sub-chievement of which goals that can be applied to individuals and units within the organization. A subgoal is attain or exceed its major an objective, the achievement of which helps the organization attain or exceed it major goals. organization Figure 12.8 A Typical Control System FEEDBACK Take Corrective Action Variance Between Performance and Goals and Standards Measure Performance Compare Performance Against Goals and Standards Provide Reinforcement Performance Meets or Exceeds Goals and Standards FEEDBACK goals. Goals and subgoals should be precise, measurable, address important issues, be challenging but realistic, and specify a time period. To illustrate the concept of a goal hierarchy, suppose that the retailer Nordstrom has a goal of attaining a 15% return on invested capital (ROIC) in the coming year. This is the company's major profitability goal. One way of achieving it is to reduce the amount of capital needed to generate a dollars' worth of sales, and a good way of doing that is to reduce the amount of capital that Nordstrom has tied up in inven- tory. How does the company do that? By turning over inventory more rapidly. Thus, Nordstrom might operate with a subgoal of turning over inventory five times in the next year. If it hits that subgoal, which is precise, measurable, challenging, and has to be achieved within a prespecified time period, the company's profitability, measured by ROIC, will increase. In fact, as explained in Strategy in Action 12.2. Nordstrom has done something very much along these lines. Standards are similar to goals but tend to be objectives that the organization is expected to achieve as a part of its routine operations, rather than a challenging goal it is striving to attain. For example, an organization might operate with standards specifying that vendors should be paid within 30 days of submitting an invoice, that customer inquiries should be answered within 24 hours, that all employees should have a formal performance review and be given written feedback once a year, that safety checks should be performed on production equipment every six months, or that em- ployees should fly coach when traveling on business trips. A key element in the control process is generating the right goals, subgoals, and standards. Managers need to choose goals and standards carefully to avoid motivating the wrong behavior. There is a saying, "You get what you measure." If you chose the wrong goals and standards, you get the wrong behavior. Dysfunctional controls will generate dysfunctional behavior. A few years ago, a placement agency decided to start evaluating and rewarding its staff based on how many job seekers they sent to a job interviews. This productivity measure seemed to produce the desired results, over the next few months; more job seekers got interviews. However, after a while the numbers started to drop off quite alarmingly. When management looked into the issue, they Establish Goals and Standards B Chapter 12 Implementing Strategy Through Organization STRATEGY IN ACTION p. 409 12.2 Goal Setting and Controls at Nordstrom A few years ago, Nordstrom, the venerable, high-end department store, was facing some challenges. Despite industry-leading sales per square foot, profits had fall en short of the company's goals for 3 years in a row and were down some 35%. The root of the problem was that poor inventory controls meant that Nordstrom either had too much merchandise that was in low de mand, or too little of the merchandise that consumers wanted. To get rid of excess inventory, Nordstrom held frequent sales, marking down items and selling them at a lower profit margin. Moreover, the failure to stock popular items meant that Nordstrom was losing high- margin sales to provide suppliers with visibility of what was selling at Nordstrom and what the reorder pattern would be, so the suppliers could adjust their production schedules accordingly. The goal was to stock only what consum ers demanded by having inventories delivered to stores on an asneeded basis. To measure the success of this program, Nordstrom focused on two metrics-inventory turnover and average inventory per square foot of selling space. When the company began to implement these systems, it was turning over its inventory 3.73 times a year, and on average throughout the year had $60 of in ventory for every square foot of selling space in a store. Three years later, as a result of better inventory controls, inventory was turning over 4.51 times a year, and the company held $52.46 of inventory for every square foot of selling space. Due to im