Question: Please read the question: Why is oracy important in Spanish literacy and literacy-based ELD? Oral language is the medium we use to make friends, earn

Please read the question: Why is oracy important in Spanish literacy and literacy-based ELD?

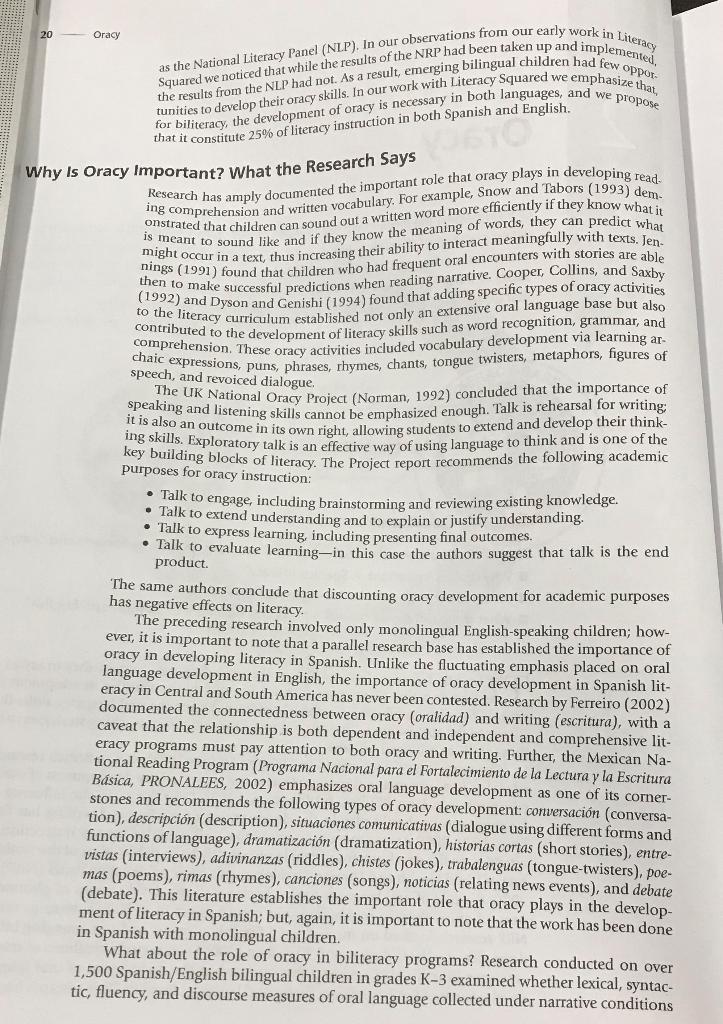

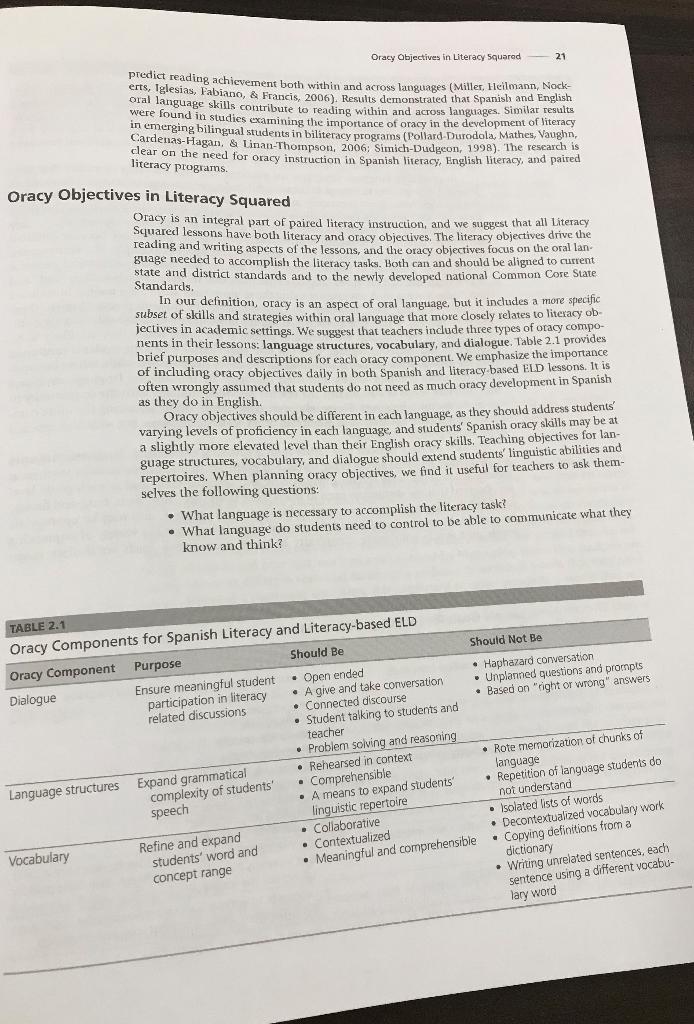

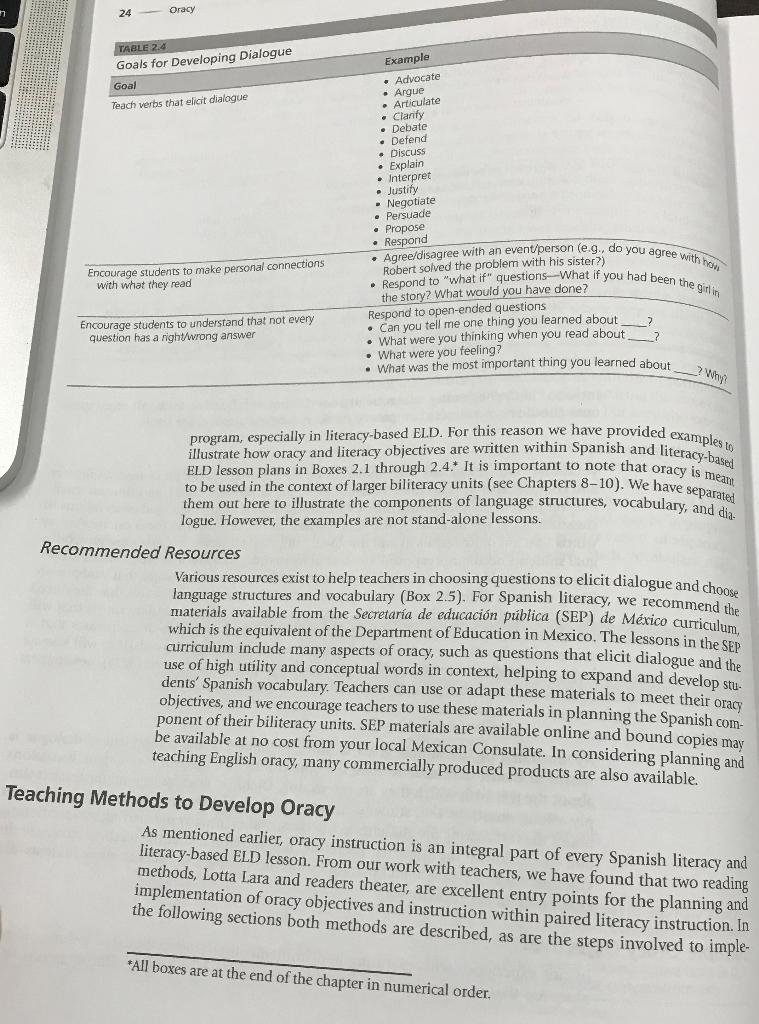

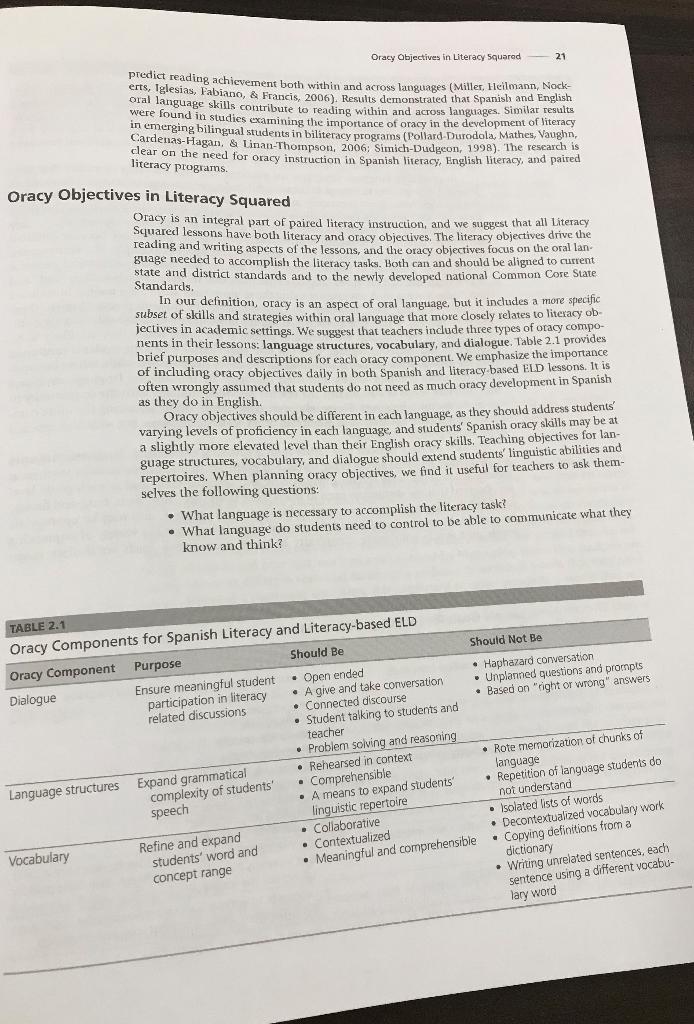

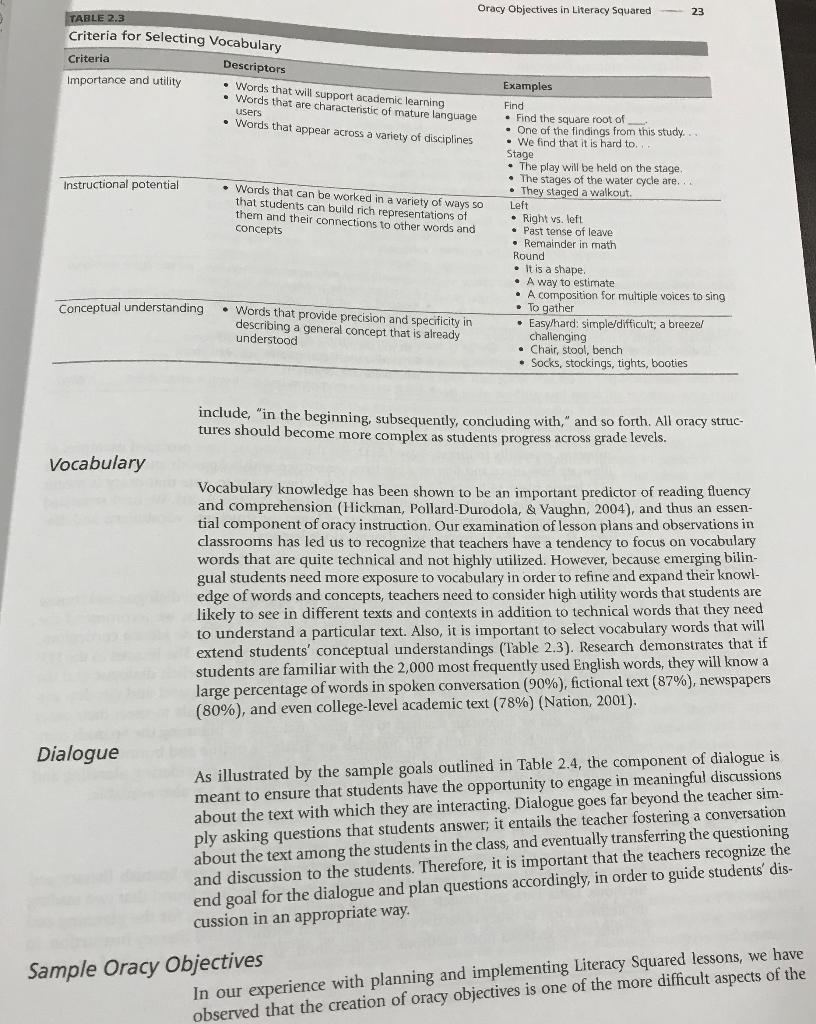

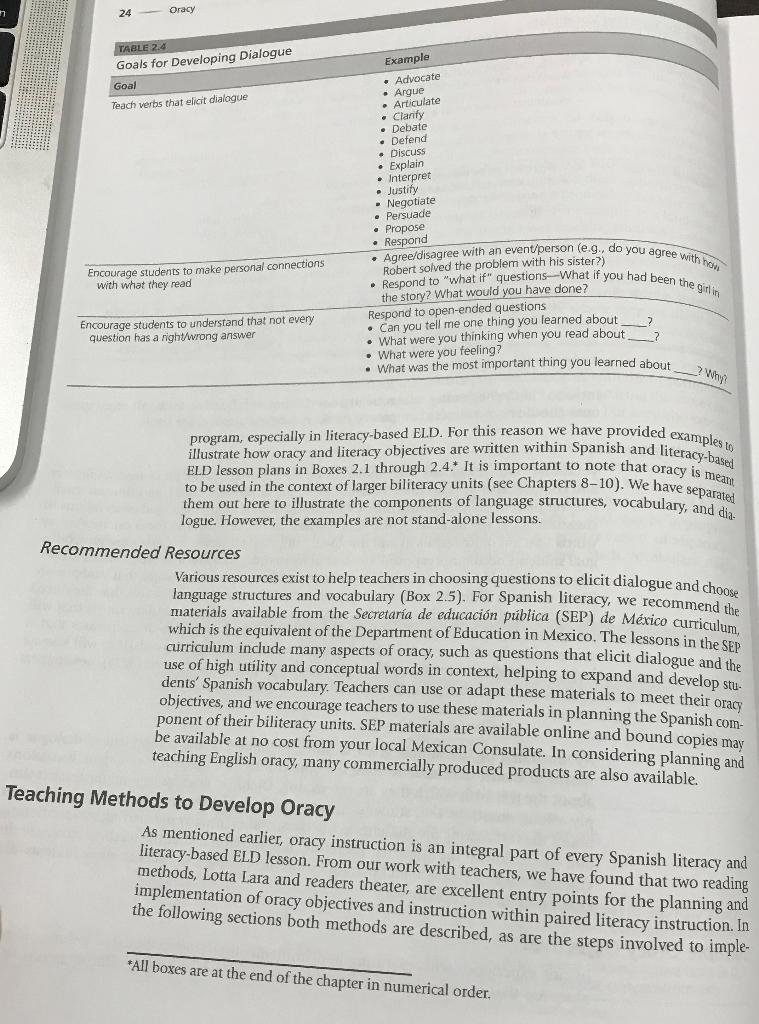

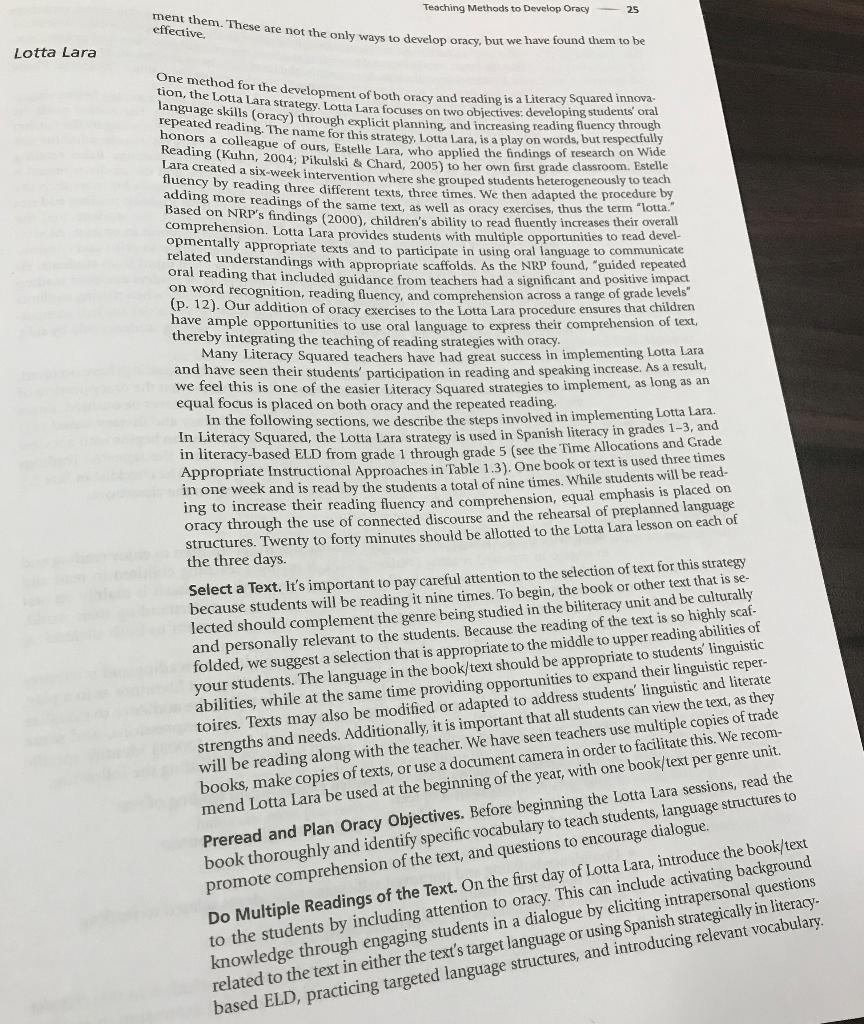

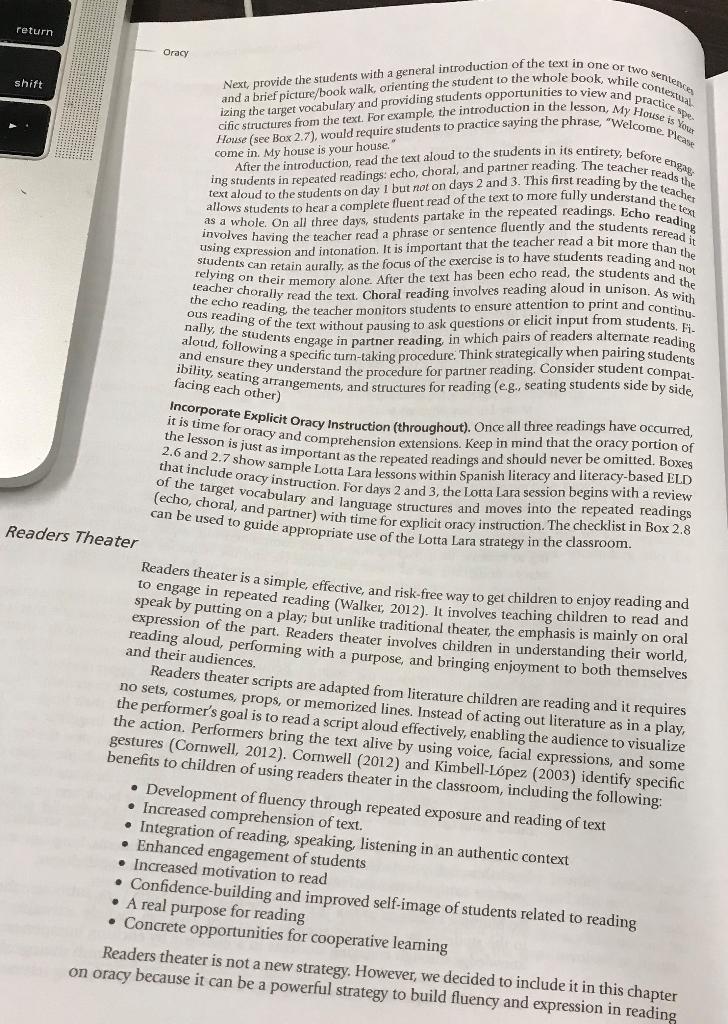

Oral language is the medium we use to make friends, earn a living and become participating members of the community. It is through speech that we assimilate the thoughts and opinions, ideas, emotions, humour, wisdom, common-sense, even moral and spiritual values of those around us and it is through perceptive listening and courteous speaking that we move towards breaking down social, professional and racial barriers. Christabel Burniston, ORACY Australia Guiding Questions What is the difference between general oral language development and oracy? Why is oracy important in Spanish literacy? Why is oracy important in literacy-based ELD? What is the difference between oracy development in Spanish and English? The holistic biliteracy framework (on the preceding page) establishes oracy as one of I the four domains of language that are essential to the effective development of biliteracy in Spanish and English. In this chapter we discuss the oral language skills that contribute to the acquisition of literacy and provide examples of teaching strategies to develop those skills in bilingual learners. The term "oracy" was coined in 1970 by Andrew Wilkinson, a British researcher and educator, in an attempt to draw attention to the neglect of the development of oral skills in education (MacLure, Phillips, \& Wilkinson, 1988). Over the years, the influence that oral language can or should play in the development of reading and writing has fluctuated. From 1970-2000 it was generally accepted that well-rounded literacy instruction included attention to the development of oral language. With the publication of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development's National Reading Panel (NRP) Report in 2000 , the role of oral language took a backseat to the development of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. It is important to note that the NRP research focused on monolingual English speakers and not emerging bilingual students. Six years later, August and Shanahan (2006) conducted a synthesis of research about emerging bilingual learners and they pointed to the importance of oral language in the development of English literacy for second language learners. This research became known Oracy as the National Literacy Panel (NI.P). In our observations from our early work in Literacy Squared we noticed that while the results of the NRP had been taken up and implemented, tunities to develop their oracy skils. In our work with biteracy Sy languages, and we propose that it constitute 25% of literacy instrucion in Is Oracy Important? What the Research Says Research has amply documented the important role that oracy plays in developing read. ing comprehension and written vocabulary. For example, Snow and Tabors (1993) demonstrated that children can sound out a written word more efficiently if they know what it is meant to sound like and if they know the meaning of words, they can predict what might occur in a text, thus increasing their ability to interact meaningfully with texts. Jennings (1991) found that children who had frequent oral encounters with stories are able then to make successful predictions when reading narrative. Cooper, Collins, and Saxby (1992) and Dyson and Genishi (1994) found that adding specific types of oracy activities to the literacy curriculum established not only an extensive oral language base but also contributed to the development of literacy skills such as word recognition, grammar, and comprehension. These oracy activities included vocabulary development via learning archaic expressions, puns, phrases, rhymes, chants, tongue twisters, metaphors, figures of speech, and revoiced dialogue. The UK National Oracy Project (Norman, 1992) concluded that the importance of speaking and listening skills cannot be emphasized enough. Talk is rehearsal for writing; it is also an outcome in its own right, allowing students to extend and develop their thinking skills. Exploratory talk is an effective way of using language to think and is one of the key building blocks of literacy. The Project report recommends the following academic purposes for oracy instruction: - Talk to engage, including brainstorming and reviewing existing knowledge. - Talk to extend understanding and to explain or justify understanding. - Talk to express learning, including presenting final outcomes. - Talk to evaluate learning-in this case the authors suggest that talk is the end product. The same authors conclude that discounting oracy development for academic purposes has negative effects on literacy. The preceding research involved only monolingual English-speaking children; however, it is important to note that a parallel research base has established the importance of oracy in developing literacy in Spanish. Unlike the fluctuating emphasis placed on oral language development in English, the importance of oracy development in Spanish literacy in Central and South America has never been contested. Research by Ferreiro (2002) documented the connectedness between oracy (oralidad) and writing (escritura), with a caveat that the relationship is both dependent and independent and comprehensive literacy programs must pay attention to both oracy and writing. Further, the Mexican National Reading Program (Programa Nacional para el Fortalecimiento de la Lectura y la Escritura Bsica, PRONALEES, 2002) emphasizes oral language development as one of its cornerstones and recommends the following types of oracy development: conversacin (conversation), descripcin (description), situaciones comunicativas (dialogue using different forms and functions of language), dramatizacin (dramatization), historias cortas (short stories), entrevistas (interviews), adivinanzas (riddles), chistes (jokes), trabalenguas (tongue-twisters), poemas (poems), rimas (rhymes), canciones (songs), noticias (relating news events), and debate (debate). This literature establishes the important role that oracy plays in the development of literacy in Spanish; but, again, it is important to note that the work has been done in Spanish with monolingual children. What about the role of oracy in biliteracy programs? Research conducted on over 1,500 Spanish/English bilingual children in grades K3 examined whether lexical, syntactic, fluency, and discourse measures of oral language collected under narrative conditions predict reading achicvement both within and across languages (Miller, Heilmann, Nockerts, Iglesias, Fabiano, \& Francis, 2006). Results demonstrated that Spanish and English. oral language skills contribute to reading within and across languages. Similar results were found in studies sxamining the importance of oracy in the development of literacy in emerging bilingual students in biliteracy programs (Pollard-Durodola, Mathes, Vaughn, Cardenas-Hagan, \& Linan-Thompson, 2006; Simich-Dudgeon, 1998). The research is clear on the need for oracy instruction in Spanish lireracy, English literacy, and paired literacy programs. Oracy Objectives in Literacy Squared Oracy is an integral part of paired literacy instruction, and we suggest that all literacy Squared lessons have both literacy and oracy objectives. The literacy objectives drive the reading and writing aspects of the lessons, and the oracy objectives focus on the oral language needed to accomplish the literacy tasks. Both can and should be aligned to current state and district standards and to the newly developed national Common Core State. Standarcls. In our definition, oracy is an aspect of oral language, but it includes a more specific subset of skills and strategies within oral language that more closely relates to literacy objectives in academic settings. We suggest that teachers include three types of oracy components in their lessons: language structures, vocabulary, and dialogue. Table 2.1 provides brief purposes and descriptions for each oracy component. We emphasize the importance of including oracy objectives daily in both Spanish and literacy based ELD lessons. It is often wwongly assumed that students do not need as much oracy development in Spanish as they do in English. Oracy objectives should be different in each language, as they should address students' varying levels of proficiency in each language, and students' Spanish oracy skills may be at a slightly more elevated level than their English oracy skills. Teaching objectives for language structures, vocabulary, and dialogue should extend students' linguistic abilities and repertoires. When planning oracy objectives, we find it useful for teachers to ask themselves the following questions: - What language is necessaly to accomplish the literacy task? - What language do students need to control to be able to communicate what they know and think? Oracy guage Structures Language structures serve as scaffolds to assist students in expanding their linguistic reper. grammatical complexity. While students may une discuss it, especially for different functions it does not mean that they have the ling). of language (eg. predicting, inferring stron students, teachers can help to ensure that they have the opportunity to engage in mean well as in more complex ways. Students need to be express their ideas more accurately, as wes to rehearse the language structures and use them provided with multiple oppored dialogues. As teachers provide these opportunities, they for real purposes in structured dialogues levels of language proficiency because different need to be mindful of students" students may be ready to take on more conplex theacher was teaching students to compare classroom we observed in Salem, Oregon, the teacher was teaded words such as "and" and and contrast and had provided language stuctures the basic words, the teacher introduced "but," After having students practice using those more basic wor st the racticed saying these the words "whereas" and "however," and together all of the storents to use this language, stuwords in context. While it may sound stilted for kinder the place where they are likely to be dents take on the language we teach and school is the plarly? When the students continued with the lesson, some students went back to the more basic words, while others incorporated the more complex words into their dialogue. By introducing language structures with different levels of complexity, the teacher provided students with the opportunity to use more complex language. Those who were ready could begin practicing the more complex language, and those who were not had other scaffolds in place, but were also exposed to the more complex language. Further, we have noticed that rather than a spiraling curriculum, language structures are frequently repeated across grade levels. For example, in one of our schools teachers at various grade levels were teaching sequencing and summarizing, and at each grade level we observed that the vocabulary used to teach these skills was, "first, then, next, and finally/ last." While this vocabulary is acceptable for students in grade 1 , and may be appropriate for grade 2, by grades 3 and 4 students should be utilizing a greater variety of sequencing words and words with more complexity to create summaries. Such vocabulary might TABLE 2.3 Oracy Objectives in Literacy Squared 23 Criteria for Selecting Vocabulary \begin{tabular}{lll} \hline Criteria & Descriptors & \\ \hline Importance and utility & - Words that will support academic learning & Examples \\ \hline \end{tabular} - Words that are characteristic of mature language - Find the square root of - Words that appear across a variety of disciplines : Whe of the findings from this study... Stage - The play will be held on the stage. - The stages of the water cycle are... include, "in the beginning, subsequently, concluding with," and so forth. All oracy structures should become more complex as students progress across grade levels. Vocabulary Vocabulary knowledge has been shown to be an important predictor of reading fluency and comprehension (Hickman, Pollard-Durodola, \& Vaughn, 2004), and thus an essential component of oracy instruction. Our examination of lesson plans and observations in classrooms has led us to recognize that teachers have a tendency to focus on vocabulary words that are quite technical and not highly utilized. However, because emerging bilingual students need more exposure to vocabulary in order to refine and expand their knowledge of words and concepts, teachers need to consider high utility words that students are likely to see in different texts and contexts in addition to technical words that they need to understand a particular text. Also, it is important to select vocabulary words that will extend students' conceptual understandings (Table 2.3). Research demonstrates that if students are familiar with the 2,000 most frequently used English words, they will know a large percentage of words in spoken conversation (90\%), fictional text (87%), newspapers (80%), and even college-level academic text (78%)( Nation, 2001). Dialogue As illustrated by the sample goals outlined in Table 2.4, the component of dialogue is meant to ensure that students have the opportunity to engage in meaningful discussions about the text with which they are interacting. Dialogue goes far beyond the teacher simply asking questions that students answer; it entails the teacher fostering a conversation about the text among the students in the class, and eventually transferring the questioning and discussion to the students. Therefore, it is important that the teachers recognize the end goal for the dialogue and plan questions accordingly, in order to guide students' discussion in an appropriate way. Sample Oracy Objectives In our experience with planning and implementing Literacy Squared lessons, we have observed that the creation of oracy objectives is one of the more difficult aspects of the program, especially in literacy-based ELD. For this reason we have provided examples to illustrate how oracy and literacy objectives are written within Spanish and literacy-based ELD lesson plans in Boxes 2.1 through 2.4. It is important to note that oracy is meant to be used in the context of larger biliteracy units (see Chapters 8-10). We have separated them out here to illustrate the components of language structures, vocabulary, and dialogue. However, the examples are not stand-alone lessons. Recommended Resources Various resources exist to help teachers in choosing questions to elicit dialogue and choose language structures and vocabulary (Box 2.5). For Spanish literacy, we recommend the materials available from the Secretara de educacin pblica (SEP) de Mxico curriculum, which is the equivalent of the Department of Education in Mexico. The lessons in the SEP curriculum include many aspects of oracy, such as questions that elicit dialogue and the use of high utility and conceptual words in context, helping to expand and develop stu. dents' Spanish vocabulary. Teachers can use or adapt these materials to meet their oracy objectives, and we encourage teachers to use these materials in planning the Spanish component of their biliteracy units. SEP materials are available online and bound copies may be available at no cost from your local Mexican Consulate. In considering planning and teaching English oracy, many commercially produced products are also available. eaching Methods to Develop Oracy As mentioned earlier, oracy instruction is an integral part of every Spanish literacy and literacy-based ELD lesson. From our work with teachers, we have found that two reading methods, Lotta Lara and readers theater, are excellent entry points for the planning and implementation of oracy objectives and instruction within paired literacy instruction. In the following sections both methods are described, as are the steps involved to imple- "All boxes are at the end of the chapter in numerical order. ment them. These are not the only ways to develop oracy, but we have found them to be effertive. One method for the development of both oracy and reading is a Literacy Squared innovation, the Lotta Lara strategy. Lotta Lara focuses on two objectives: developing student's oral language skills (oracy) through explicit planning, and increasing reading fluency through repeated reading. The name for this strategy, Lotta Lara, is a play on words, but respectfully Reading (Kulleague of ours, Estelle Lara, who applied the findings of research on Wide Lara creading (Kuhn, 2004; Pikulski \& Chard, 2005) to her own first grade classroom. Estelle Lluena created a six-week intervention where she grouped students heterogeneously to teach fluency by reading three different texts, three times. We then adapted the procedure by adding more readings of the same text, as well as oracy exercises, thus the term "lotta." Based on NRP's findings (2000), children's ability to read fluently increases their overall comprehension. Lotta Lara provides students with multiple opportunities to read developmentally appropriate texts and to participate in using oral language to communicate related understandings with appropriate scaffolds. As the NRP found, "guided repeated oral reading that included guidance from teachers had a significant and positive impact on word recognition, reading fluency, and comprehension across a range of grade levels" (p. 12). Our addition of oracy exercises to the Lotta Lara procedure ensures that children have ample opportunities to use oral language to express their comprehension of text, thereby integrating the teaching of reading strategies with oracy. Many Literacy Squared teachers have had great success in implementing Lotta Lara and have seen their students' participation in reading and speaking increase. As a result, we feel this is one of the easier Literacy Squared strategies to implement, as long as an equal focus is placed on both oracy and the repeated reading. In the following sections, we describe the steps involved in implementing Lotta Lara. In Literacy Squared, the Lotta Lara strategy is used in Spanish literacy in grades 1-3, and in literacy-based ELD from grade 1 through grade 5 (see the Time Allocations and Grade Appropriate Instructional Approaches in Table 1.3). One book or text is used three times in one week and is read by the students a total of nine times. While students will be reading to increase their reading fluency and comprehension, equal emphasis is placed on oracy through the use of connected discourse and the rehearsal of preplanned language structures. Twenty to forty minutes should be allotted to the Lotta Lara lesson on each of the three days. Select a Text. It's important to pay careful attention to the selection of text for this strategy because students will be reading it nine times. To begin, the book or other text that is selected should complement the genre being studied in the biliteracy unit and be culturally and personally relevant to the students. Because the reading of the text is so highly scaffolded, we suggest a selection that is appropriate to the middle to upper reading abilities of your students. The language in the book/text should be appropriate to students' linguistic abilities, while at the same time providing opportunities to expand their linguistic repertoires. Texts may also be modified or adapted to address students' linguistic and literat strengths and needs. Additionally, it is important that all students can view the text, as the will be reading along with the teacher. We have seen teachers use multiple copies of tra books, make copies of texts, or use a document camera in order to factitate this. We teco per gente un mend Lotta Lara be used at the beginning of the year, with one book lext per gente un lara sessions, read Preread and Plan Oracy Objectives. Before beginning the Lotta Lara sessions, reas book thoroughly and identify specific vocabulary to teach students, lang enage stialogue. promote comprehension of the text, and questions to encourage dialogue. Do Multiple Readings of the Text. On the furst day of Lotta Lara, introduce the bo to the students by including attention to oracy. This can include activating back a dialogue by eliciting intrapersonal q Oracy cific structures from the text. For example, the introduction in the lesson, My House is House (see Box 2.7), would require students to practice saying the phrase, "Welcome pout House (see Box 2.7), would require stur After the introduction, read the text aloud to the students in its entirety, before engag. ing students in repeated readings: echo, choral, and partner reading. The teacher reads the text aloud to the students on day 1 but not on days 2 and 3 . This first reading by the teacher allows students to hear a complete fluent read of the text to more finly understand the text involves having the teacher read a phrase or sentence fluently and the students reading using expression and intonation. It is important that the teacher read a bit more than the students can retain aurally, as the focus of the exercise is to have students reading and not relying on their memory alone. After the text has been echo read, the students and the teacher chorally read the text. Choral reading involves reading aloud in unison. As with the echo reading the teacher monitors students to ensure attention to print and continu. ous reading of the text without pausing to ask questions or elicit input from students. Finally, the students engage in partner reading, in which pairs of readers alternate reading aloud, following a specific turn-taking procedure. Think strategically when pairing students and ensure they understand the procedure for partner reading. Consider student compatibility, seating arrangements, and structures for reading ( e. ., seating students side by side, facing each other) Incorporate Explicit Oracy Instruction (throughout). Once all three readings have occurred, it is time for oracy and comprehension extensions. Keep in mind that the oracy portion of the lesson is just as important as the repeated readings and should never be omitted. Boxes 2.6 and 2.7 show sample Lotta Lara lessons within Spanish literacy and literacy-based ELD of the target vacy instruction. For days 2 and 3 , the Lotta Lara session begins with a review (echo, choral, and palary and language structures and moves into the repeated readings can be used to guicterther) with time for explicit oracy instruction. The checklist in Box 2.8 Lide appropriate use of the Lotta Lara strategy in the classroom. Readers theater is a simple, effective, and risk-free way to get children to enjoy reading and to engage in repeated reading (Walker, 2012). It involves teaching children to read and speak by putting on a play; but unlike traditional theater, the emphasis is mainly on oral reading alos of the part. Readers theater involves children in understanding their world, and their audiences. Readers theater scripts are adapted from literature children are reading and it requires no sets, costumes, props, or memorized lines. Instead of acting out literature as in a play, the performer's goal is to read a script aloud effectively, enabling the audience to visualize the action. Performers bring the text alive by using voice, facial expressions, and some gestures (Cornwell, 2012). Cornwell (2012) and Kimbell-Lpez (2003) identify specific benefits to children of using readers theater in the classroom, including the following: - Development of fluency through repeated exposure and reading of text - Increased comprehension of text. - Integration of reading, speaking, listening in an authentic context - Enhanced engagement of students - Increased motivation to read - Confidence-building and improved self-image of students related to reading - A real purpose for reading - Concrete opportunities for cooperative learning Readers theater is not a new strategy. However, we decided to include it in this chapter acy because it can be a powerful strategy to build fluency and expression in reading and can be used to engage students in orpo to interact with and comprehent in oracy strategies that whtimutely deepen their ability reading. The readers theaterng reading readen theater is another way to enhance toy ency through multiple readings of providen an opportunity for students to develop thetheater scripts be created in both tea, As with all by using expressiveness, intonation, and Creating the Scripts. Readers sthe panish and English. strategies, we suggest that readers papers, or magazine stories, parts of may be performed with many kinds of literature: script. We suggest that teaches, Not all literature, poetry, folk tales, works of nonfiction, news- - Is interesting or has coms look for literature however, makes a good readers theater - Uses dialogus story line, intering content. - Is not filled with descriptive passages - Flows at a steady pace descriptive passages While teachers of students in upper elementary or middle school can and should encourage their students to create and write their own readers theater scripts, we suggest. English. It is not necessary to use a piece of literature in its entirety; in fact shortened ver. the key is to be sure to keep in me especially effective in literacy-based EuD. However, piece of text. Choose text they mind the reading level of the students when selecting a following list is a basic sequence for creatioud successfully, given repeated practice. The 1. Choose the piece of text you wish to and implementing readers theater script: 2. Determine what portions you wish to adapt to script form. acters, or topic and which of the text to leave in to be true to the story line, char- 3. Delete the less critical passages: descripted. 4. Rewrite or modify those passages: descriptions, transitions, and so forth. 5. Keep speeches and narrative passages that need to be included but require adaptation. 6. Divide the parts for the readers. 7. Have children use highlighters. the part and read hexpressively, to mark parts and demonstrate how to interpret ous stage positions. 8. Give the students lots of time to prepare, practicing their roles in different ways: individually and in small groups, privately, and in front of others. 9. Send a copy of the script home for parents to read and practice with their children. 10. Rehearse with the readers, providing needed direction and support regarding their interpretation, pacing, expression, volume, positions, and motions. 11. Begin with short presentations. 12. Perform for an audience as often as possible. 13. Use props sparingly. Using Bilingual Books. In order to illustrate how to use bilingual books to create reade theater, we have included excerpts from the beginning and end of a readers theater lessi and script (Box 2.9) that was created from the bilingual book Pepita Talks TwicelPef habla dos veces (Lachtman, 1995). In this case, it is being used to build fluency in Engl This particular book lends itself to the creation of a readers theater because it has mul characters (and hence many parts for readers), has repeated phrases that lend thems to choral reading by the class, and deals with a theme that is culturally relevant to gent bilingual children. Conducting the Lesson. Finally, readers theater used to develop oracy and fluency an excellent source of dialogue related to text and reader performance. Teachers engage students in dialogues about the characters and actions in the readers interpret the vocabulary and actions in the text. We suggest that readers theater can start being used in the middle of grade 1 , in both Spanish and English, and that teacher and peer feedback be incorporated into the routines for readers theater. Teachers will need to model how to give feedback, and all feedback should be presented positively. This will also make those children who are viewers of the readers theater better and more positive listeners. Box 2.10 presents a checklist for assessing effective reading in readers theater presentations. We suggest that teachers use this checklist as a way of encouraging dialogue related to the performance of readers theater. Conclusion In this chapter we introduced oracy, the first domain of language of the holistic biliteracy framework, considered essential to biliteracy instruction and development. We provided tures, diations for generating oracy lessons that focus on the creation of sentence struchave createdue, and vocabulary. We also provided samples of how some of our teachers sons should oracy lessons as a part of larger biliteracy units. We emphasize that oracy lesof a holistic bilitereated or taught in isolation; instead, they should be included as part sive biliteracy program Questions for Reflection and Action - What other methods could you use to develop oracy? - With other teachers at your school, generate a list of potential books to use for Lotta Lara and other oracy activities and create book units in Spanish and English using the three aspects of oracy (language structures, vocabulary, and dialogue). - What books, poetry, or stories could be used to create readers theater scripts