Question

Q: Is the total project budget of $20M reasonable for this engagement? What assumptions do you need to make to answer this question? Case: On

Q: Is the total project budget of $20M reasonable for this engagement? What assumptions do you need to make to answer this question?

Case:

On a Monday morning in January, 1996, Elaine Kramer was in her Philadelphia office catching up on e-mail. She had been in Minneapolis the previous week for a series of meetings between her firm, Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group/ICS, and the executives and plant managers of Vans delay Industries Inc., a major producer of industrial process equipment. The week had ended with the two companies signing a contract to work together on a large information systems implementation project.

Her phone rang. This is Elaine Kramer.

Hi, Elaine, this is George Hall. I manage Van delays Dumbarton plant; we met at the project kick-off meetings last week.

Oh, yes - how are you, George? I really enjoyed the presentation on your pull-based manufacturing project. You guys have generated some really impressive results. What can I do for you?

I was just wondering if I could start getting my people signed up for training on the R/3 system. I know it's early, but we're really eager to dig in here. Your presentation got a lot of people excited about getting rid of our plants old mainframe. We want to get an R/3 team together so were ready to work on the system as soon as its installed at Dumbarton.

Well, we havent started putting training schedules together yet...

Well, keep us in mind when you do. Like I said in the presentation, we're a bunch of tinkerers, and that's what has helped us improve so much over the past few years. We think R/3 can really help us past some of our current roadblocks, so were eager to start experimenting with it.

OK, let me get back to you once were further along with training plans.

After Kramer hung up the phone she mentally replayed the conversation; it raised an issue that had been in the back of her mind since the meetings. How much should the plants in the network be encouraged to modify their local set-up of the new computer system once it had been installed?

Project Background

Van delay had decided in 1995 to implement a single Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) information system throughout the corporation. The firm had chosen the R/3 system from SAP AG, a German company that was the market lead in ERP products. Van delay hoped that the R/3 implementation would end the existing fragmentation of its systems, allow process standardization across the corporation, and give it a competitive advantage over its rivals.

Van delay managers realized that putting R/3 in place would be an enormous effort, of which installation of hardware and software was only a small part. For help with all aspects of the project, from the technical details of an ERP system to widespread business practice changes, Van delay had engaged the Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group / ICS. ICS assisted clients in managing fundamental changes of the kind entailed by an ERP system, and had significant expertise with SAPs R/3 product.

Kramer, who had been with the firm for over 5 years, had been chosen to lead the project. At the meetings in Minneapolis she had been impressed with Van delays enthusiasm for the project. The plant managers seemed especially excited; many of them had said that they considered their existing information systems an impediment, rather than an aid, to efficient production.

George Hall certainly seemed pleased at the thought of R/3 in his plant, but Kramer was not entirely calmed by their conversation. Hall had evidently assumed that Dumbarton would be free to modify the system at will; Kramer knew that this would not be the case. She wondered how to respond to his request for training, and how to let him and the other plant managers know that all decisions about R/3 were not under their control.

Van delay Industries

Company Background

Van delay Industries, Inc. was an $8B corporation that manufactured and distributed industrial process equipment used in the production of rubber and latex. The company was founded in Minnesota during World War II; its initial products proved important on the Home Front, enabling the much greater productivity required by the war effort. From the beginning, Van delays offerings were known for their design quality and innovative engineering; company lore held that this was because wartime rubber shortages necessitated precise, waste less production.

Markets for Van delay products were extremely healthy throughout the following decades, and the firm steadily expanded, partly by building new sites and partly by acquiring smaller firms1. The company also steadily expanded its product lines, eventually supplying a range of process industries. Van delay plants were treated as revenue centers and typically were allowed a high degree of independence, provided that they maintained acceptable profit margins. At its peak, the company employed 30,000 people and manufactured on four continents. Employees tended to remain with Van delay for a long time, taking advantage of generous pay and benefits and a stimulating work environment.

The company began to experience difficult times beginning in the mid 1980s as a result of market shifts and severe competitive pressures. Three strong foreign competitors emerged, offering less expensive alternatives in many of Van delays product lines. These machines typically did not include all of the features of the comparable Van delay product, but were substantially (20-30%) cheaper. As a result, the American companys traditional emphasis on features and customizability became a liability. Its manufacturing operations were never intended to be low cost, but its products could no longer command a large price premium once suitable substitutes were available. The firms traditionally long lead times also became a problem; the new entrants could fill customer orders much more quickly.

Van delay fought hard over the next ten years to learn new technologies and new ways of doing business. It adopted lean production methods, rationalized its product lines, and introduced new, simpler and cheaper machines. It also closed three plants, leaving eight in operation2 and had the first layoffs in its history, reducing its total headcount to 20,000 people. Many of these efforts paid off, and the company returned to profitability in the mid 1990s.

During this decade of realignment Van delays executives realized that they would have to accord much higher priority to manufacturing and order fulfillment in order to further drive down costs. They also needed to become quicker; the companys new machines were popular, but still had longer lead times than competitors. Internal investigations had shown that actual manufacturing and material movement times accounted for less than 5% of total lead times experienced. Large parts of the remaining time, Van delay found, were devoted to information processing and information transfer steps. This was partly because the computer systems in use across the firm to guide order fulfillment and production activities were poorly integrated, and in some cases completely incompatible.

Information Systems

Each plant had selected its own system for manufacturing resource planning (MRP), the software that translated customer demands into purchasing and production requirements. In addition, many sites had also installed specialized software to help with forecasting, capacity planning, or scheduling. Information systems for human resources management had also been selected individually. There was a single corporate financial information system, to which each site had built an interface for automatic electronic updates, but this was the only example of corporation- wide systems integration.

As Van delay reviewed its operations, it uncovered several examples of how this patchwork of information systems added time and expense to the production cycle. Examples included:

Scheduling: The plants dissimilar manufacturing software often made integration across sites difficult. For example, one of Van delays American plants made a variety of machined and stamped metal parts which were used by the other North American assembly sites. This plant used an outdated MRP system which required all data to be entered manually. Requirements from all downstream users were keyed in at the beginning of each week, a task that required almost a full day. No other inputs were allowed during the week, and the plant was deluged with complaints about its responsiveness.

Forecasting: Van delays European planning group used a forecasting program which grouped all demand for an item into one monthly bucket. Plants were then free to decide when to build the product within that month. Customer orders, however, usually requested delivery within a specific week. If these requests did not line up with the months production plan by chance, late shipments resulted.

Order management: Customer orders were taken manually by an inside sales organization in each region (North America, Europe, and Asia), then routed via fax to the appropriate plant where they were keyed in to that sites order entry system. Faxes, and therefore orders, were sometimes lost.

Human resources: When a Van delay employee transferred from one location to another, her complete employee record had to be copied. Because of incompatible human resources software, this data often had to be manually re- entered. In addition to being redundant and time-consuming, this meant that the confidentiality of the information was difficult to guarantee.

Financials and Accounting: The manufacturing software used within most Van delay plants was not integrated with the sites financial package, so information such as labor hours charged to a job, materials purchased, and orders shipped had to be entered into both systems. This introduced potential for error, and necessitated periodic reconciliations.

Business Practices

Van delay sites operations practices were as varied as their information systems. There was no uniformly recognized best way to invoice customers, close the accounts at month end, reserve warehouse inventory for a customers order, or carry out any of the hundreds of other activities in the production process that required computer usage or input. At the kick-off meetings, Kramer had heard horror stories about flawed processes uncovered by plant managers. Some of them were quite vivid:

I walked down to my receiving dock a few days ago and just watched what happened each time a suppliers truck unloaded. First, our receiving guys would verify the quantities. Then theyd leave the boxes on the dock and take the packing lists over to a terminal for our quality system. If it said that the part needed incoming inspection, theyd move the boxes over to quality control. If there was no inspection, theyd take the list over to another terminal and enter the received quantities into the purchasing system, then theyd move the boxes and the list over to stores. Meanwhile, the stores guy is working through a backlog of these boxes, entering the stockroom bin numbers of all the items hes shelved. And if theres a discrepancy in the packing list or a high-priority item hits the dock, things get real complicated.

- Teri Buhl, Fort Wayne (IN) plant manager

When I started at the plant last year, I couldnt believe how work got scheduled on the floor. Theyd started a system of putting a green tag on high priority work orders to flag that they should be at the head of the queue. That worked for a while, but then someone decided that really high priority jobs should get a red tag. You can guess how it went from there. By the time I got there, no job had a prayer unless it had some kind of tag on it and there were at least a half-dozen color combinations in play. Our starting queues looked like Christmas trees.

- Alain Brasseux, Marseilles plant manager

To alleviate these problems with systems and practices, Van delay decided to purchase and install a single ERP system, which would incorporate the functions of all the previously fragmented software. The company would also use this effort as an opportunity to standardize practices across sites.

Van delay saw one other major benefit from an ERP system: gaining visibility, in a common format, over data from anywhere in the company. The company anticipated that once the software was in place, authorized users would be able to instantly see relevant information, no matter where it originated. This would provide the ability to co-ordinate and manage Van delay sites more tightly than ever before; plants could see what their internal customers and suppliers were doing, and network-level managers could directly compare performance across locations.

After a review of leading ERP vendors and implementation support consultants, Van delay decided to purchase SAPs R/3 software and put it in place with the help of Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group / ICS.

The Software Vendor: SAP

Company Background

SAP AG was founded in 1972 in Waldron, Germany with the goal of producing integrated application software for corporations. These applications were to include all of the activities of a corporation, from purchasing and manufacturing to order fulfillment and accounting. SAPs first major product was the R/2 system, which ran on mainframe computers. R/2 and its competitors came to be called Enterprise Information Systems (EISs). Within manufacturing firms, they were also known as Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems to reflect that they incorporated and expanded on the functions of previous MRP systems.

SAP was one of the first ERP vendors to realize that powerful and flexible client-server computing technologies developed in the 1980s were likely to replace the established mainframe architectures of many large firms. The company began work on a client-server product in 1987 and released the R/3 system in 1992. R/3 capitalized on many of the advantages of client-server computing, including:

Ease of use. Client-server applications often used personal computer-like graphical user interfaces. They also ran on the familiar desktop machines used for spreadsheets and word processing.

Ease of integration. The flexible client-server hardware and operating systems could be more easily linked internally (to process control equipment, for example) and externally, to Wide-area networks and the Internet.

Scalability, or the ability to add computing power incrementally. Companies could easily expand client-server networks by adding relatively small and cheap machines. With mainframes, computing capacity had to be purchased in large chunks.

More open standards. The operating systems most used for client-server computing were non-proprietary, so hardware from different manufacturers could be combined. In contrast, most mainframe technologies were proprietary, so a mainframe purchase from IBM or Digital locked in the customer to that vendor.

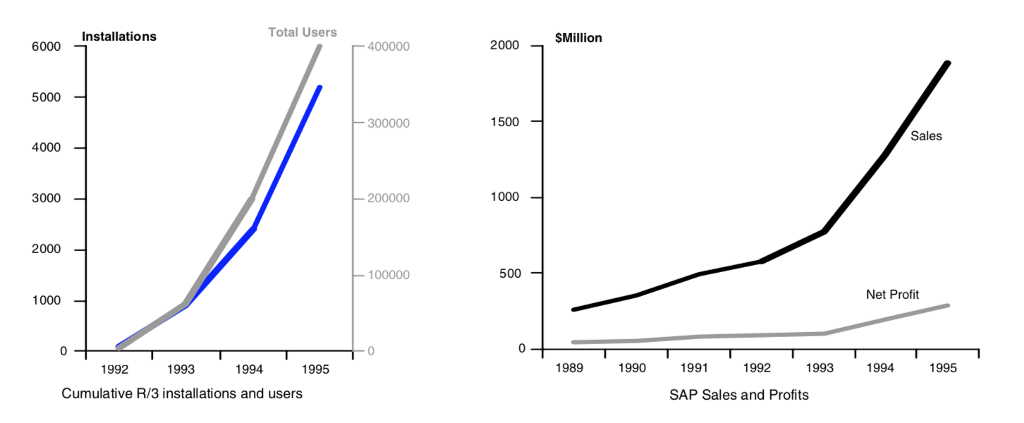

As Figure 1 shows, R/3 was extremely successful and fueled rapid growth at SAP. By 1995, the firm was the 3rd largest software company in the world (see Exhibit 1). Expansion was especially rapid in North America, where SAP went from a very small presence in 1992 to $710M in sales in 1995. This success was due to several factors, including:

Client-server technology. As large firms moved from mainframe to client-server architectures in the early 1990s, the R/3 system was available to them. Meanwhile, many suppliers of existing legacy systems did not have client-server applications ready for market.

Modularity, functionality, and integration. R/3 functionality included financials, order management, manufacturing, logistics, and human resources, as detailed in Exhibit 2. Prior to the arrival of ERP, these functions would be scattered among several systems. R/3 integrated all of these tasks by allowing its modules to share and transfer information freely, and by centralizing all information in a single database which all modules accessed.

Marketing Strategy SAP partnered with most large consulting firms. Together, they sold R/3 to executives as part of a broader business strategy, rather than selling it to Information Systems managers as a piece of software.

Figure 1: Growth of SAP and the R/3 System (Source: SAP)

R/3 Usage: transaction screens and processes

On a users machine, R/3 looked and felt like any other modern personal computer application; it had a graphical user interface and used a mouse for pointing and clicking. Users navigated through R/3 by moving from screen to screen; each screen carried out a different transaction. Transactions included everything from checking the in-stock status of a component to changing an assemblys estimated cost; Exhibit 3 gives an example of a transaction screen.

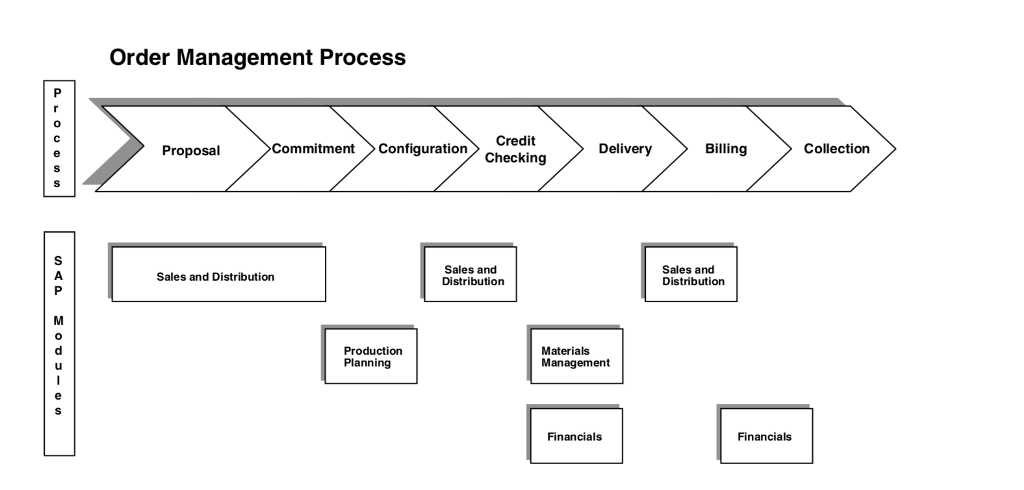

A full SAP implementation, including all standard functions, incorporated hundreds of possible transactions. Most common business processes included multiple transactions and cut across more than one functional area or software module. Figure 2 outlines the process of taking a customer order, and shows the SAP modules involved at each step. It shows that without ERP this process could involve three separate information systems -- Sales and Distribution, MRP, and Accounting and Financials. With R/3, each step would require a different transaction screen, but they would all be part of the same system. They would thus be sharing and updating the same information. This elimination of redundant entry and hand-offs between applications was one of the chief advantages of ERP systems.

Order Management Process

Figure 2: SAP modules involved in a single business process

R/3 Usage: system configuration

Configuration Tables

Although R/3 was intended as a "standard" application that did not require significant modification for each customer, it was still necessary to configure the system to meet a company's specific requirements. Configuration was accomplished by changing settings in R/3 configuration tables.

R/3s approximately 8000 tables defined every aspect of how the system functioned and how users interacted with it; in other words, they defined how all transaction screens would look and work. To configure their system, installers typically built models of how a process should work, then turned these into scripts, and finally translated scripts into table settings. For example, after writing a script that defined how a new customer order would be entered, Van delay would know whether the order taker should have the ability to override the products price field on the order entry screen.

During an implementation, this configuration activity had to be replicated for all relevant processes and required a great deal of time and expertise. People who were adept at this work, and who understood the impact of each table change, were a feature of every R/3 implementation. Kramer would be relying on several of them at ICS to work closely with the Van delay project team.

Added Functionality

Although the R/3 system was generally recognized to contain more functionality than its competition, it typically could only satisfy 80-95% of a large company's specific business requirements through standard configuration table setting work3. The remaining functionality could be obtained in four ways:

Interfacing R/3 to existing legacy systems

Interfacing R/3 to other packaged software serving as "point solutions" for specific tasks

Developing custom software that extended R/3's functionality, and was accessed through standard application program interfaces

Modifying the R/3 source code directly (This approach was strongly discouraged by SAP and could lead to a loss of support for the software.)

The Consultants: Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group / ICS Company Background

Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group (the Consulting Group) was the consulting division of Deloitte & Touch, one of the Big 6 audit and tax firms and the product of the 1989 merger of Deloitte, Haskins & Sells and Touch Ross. Consulting had been an important activity for the predecessor firms since the 1950s, and accounted for over 15% of total Deloitte & Touch revenues by the mid-1990s4. In 1995, the Consulting Group generated slightly over $1 billion in revenues and employed 8,000 professionals in more than 100 countries.

Deloitte & Touch Consulting Group / ICS was the subsidiary of the Consulting Group which specialized in SAP implementations, offering complementary software products, education and training, and consulting in business process reengineering and change management. ICS was one of the largest worldwide providers of SAP implementation services and one of the most rapidly growing sections of the Consulting Group, employing over 1300 professionals on four continents in 1995.

ICS had developed a considerable knowledge base in SAP systems; over 50% of its consultants had more than two years experience with the products. ICS had won SAPs Award of Excellence, which was based on customer satisfaction surveys administered by the software maker,

every year since its inception. SAP had also named ICS as an R/3 Global Logo Partner. According to SAP5,

The aim of these partnerships is to establish, extend and enhance R/3 expertise. In order to keep these logo partners up to date with the latest developments, SAP maintains very close contact with them, providing an intensive flow of information and offering the following services:

an R/3 System for internal training; regular R/3 logo partner forums, workshops and training sessions; access to SAP Info Line, SAP's internal information system; second level support from SAP Consulting, including the consultant hotline.

ICS professionals ranged from general management consultants to SAP specialists. The specialists focused on a functional or technical area of SAP and worked as, for example, experts on the Materials Management functions or programmers in the systems native ABAP/4 language. Management consultants, meanwhile, had experience with process re-design, systems implementation, change management, or project management. More senior personnel often combined both types of skills.

Technology-Enabled Change

ICS consultants had adopted a common set of principles for leading large-scale change in a firm. According to Kramer:

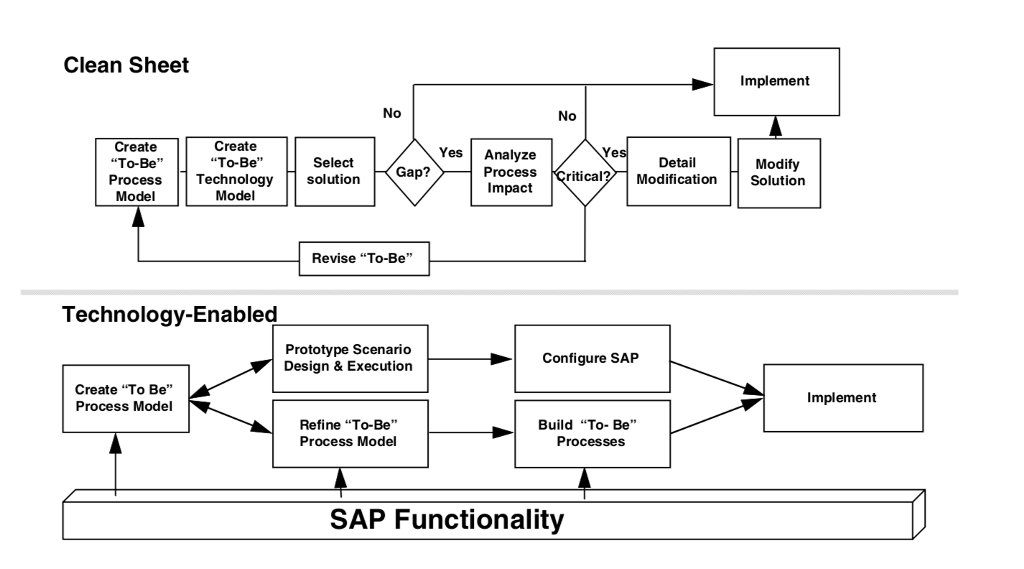

Change occurs at several levels in an organization: strategy, process, people, and technology. Depending on the particular client situation, there are two approaches which can be taken. The first is clean sheet, where all four dimensions of organizational change are explored without constraints. The second is technology-enabled change. In this situation, the primary technology is selected early in the process and more strongly influences the other three dimensions of strategy, people, and processes, but still enables significant overall business change. The introduction of powerful, flexible, enterprise-wide solutions such as SAP is driving this approach as clients are looking to concurrently replace mainframe legacy systems and achieve significant operating improvement.

The right approach to change is determined based on clients situation. In Van delays case, the latter approach is more appropriate since they have already made the decision to go with SAP. To guide a client through all phases of implementation, ICS uses a structured approach tailored to the clients situation. This methodology captures the collective learning of the practitioners and creates a roadmap for the SAP implementation.

Figure 3 illustrates how ICS viewed the difference between the technology-enabled and clean sheet approaches to process redesign.

Van delay management projected that the implementation would take 18 months and require the full-time efforts of 50 people, including consultants (both process redesigns and SAP specialists) and employees, as well as part-time involvement from many employees at each site. The total budget for the project was $20 million, including hardware, software, consulting fees, and the salaries and expenses of involved employees. Based on her prior experiences, Kramer felt that the timeline and budget were very aggressive for the scope of the implementation; she wondered whether all of the elements were in place to achieve the desired change.

R/3 software was to be implemented at Van delays eight manufacturing sites and four order entry locations6, and at the corporate headquarters in Minnesota. The plant installations would take the longest; each one would require a lengthy preparation period to align its operations with the new business practices. Kramer estimated that two thirds of all Van delay employees would need training on how to use the new system, with the amount of training required ranging from one day for casual users to two weeks for those who would use R/3 heavily in their jobs.

Initially, the project team would focus about 80% of its effort on designing the to be process model of the organization, and 20% on issues relating to the system implementation. This reflected the fact that the project would begin by establishing the need for business change and setting performance targets, rather than installing software. In the later phases of the implementation the required mix of consulting skills would shift to deeper SAP expertise. During the activities of system configuration, testing, and delivery, the emphasis would be reversed; 80% concentration on SAP implementation, 20% on process design.

Team structure

As Kramer put it:

A project like this one requires a variety of skills. I think the most important are project management ability, SAP expertise, business and industry understanding, systems implementation experience, and change leadership talent. Well need to field a joint client / consultant team with the right mix of skills at the right time.

Van delay and ICS had decided to use two teams for managing the project. While senior management on the steering committee would decide strategic issues relating to the implementation, Table 1 shows that the project team would be responsible for the bulk of the decisions made, and for the ones which determined how the system would actually work. For this reason, Kramer was eager to structure this team correctly.

Kramers experience had shown her that there were two basic ways to select participants for the project team. She could simply present a list of the required skills and characteristics for team members to senior-level management and ask them to nominate and approach the people who they felt would be best for the job. Alternatively, she could mandate that the team contain at least one representative from each of Van delays implementation sites around the world. While this approach might sacrifice some quality and depth on the team, it could also help to ensure that each site would have a project champion from the outset.

Managing Change

Selecting the best development team was only one of Kramers considerations as she prepared to dig in on the Van delay engagement. She had led ERP implementations before and was aware of the challenges involved in assisting a large organization as it attempted to change and standardize its practices. She placed these challenges into a few categories:

Centralization vs. autonomy

There was no way to involve all users in the decisions that would affect them and their jobs. This could create a strong temptation for people to second guess these choices, and to alter the system that was delivered to them. This was especially true at Van delay, which had a strong tradition of encouraging innovation and autonomy among its employees, as George Hall had demonstrated. Should this tinkering be encouraged, or should systems and processes be locked- down as much as possible? Could Kramer and her teams be confident that their decisions were the right ones throughout Van delay? If so, should processes be tightly centralized and controlled, and tinkering (and therefore possible innovation) strongly discouraged? If not, what was the point of the long and thorough development and implementation cycle? Kramer had a strong bias toward input by many, design by few, but how could she put this rule into practice?

She knew that this issue was particularly important for global companies like Van delay. Just as cultures and currencies varied across countries, so did standard business practices, outlooks, and relationships between customers and suppliers. The implementation team would have to be sure that any universal processes did not run afoul of local ones.

A closely related question concerned standardization on externally defined best practices. Much of the consultants expertise came from their previous engagements; they knew what had worked and what hadnt for other clients. In addition, SAPs standard capabilities were the result of the firms accumulated knowledge about the requirements for ERP software. There was thus a set of outside practices involving systems, operations, and processes that could be used at Van delay. Kramer wondered how they should be incorporated into the project -- were they a starting point or the final word?

Kramer could already see one area where plants would have to give up some of their autonomy. R/3 required that each item have a single, unique part number, and Van delay executives wanted common part numbers across all sites so they could see accurate consolidated information about production, orders, and sales. Each plant, however, had developed its own internal part numbering system over time. Replacing these schemes would be a major effort, involving everything from stockroom storage bins to engineering drawings to part stamping equipment. In addition, plant personnel would have to forget the previous numbers, which they often knew by heart. Kramer saw that part number standardization would be part of the Van delay R/3 implementation, that the plants would probably resist it, and that they would have no choice in the matter.

Change agents and organizational inertia

Kramer also knew from experience that large implementations went best when a critical mass of early leaders -- people who were enthusiastic about the work of change and who were respected within the firm -- had been built. She also knew, however, that even with committed change agents in place, most people did not completely accept a new system until they really believed that it was inevitable. She found this paradoxical; companies committed substantial resources up front and stated clearly that the new system was a given, but most employees remained skeptical for a long time. Why was this, and what could she and her early movers do about it?

Software

Although R/3 had broad capability, there would be situations where it would not exactly fit the desired Van delay process design. Kramer had observed three primary alternatives to addressing this situation:

1) Change the business process to match the capabilities of the software

2) Interface R/3 to another package or custom solution

3) Extend the R/3 system to precisely match the business requirements.

What guidelines should she follow in selecting among these options?

Kramer knew that she would have to get back to George Hall soon about training for his site, but she was unsure what to tell him. If his people werent allowed to experiment with the system as much as they wanted, would his enthusiasm for the project turn into hostility?

Total Users Installations SMillion 6000 400000 2000 5000 300000 1500 Sales 4000 3000 200000 1000 2000 100000 500 Net Profit 1000 1992 1993 1994 1995 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Cumulative R/3 installations and users SAP Sales and Profits Total Users Installations SMillion 6000 400000 2000 5000 300000 1500 Sales 4000 3000 200000 1000 2000 100000 500 Net Profit 1000 1992 1993 1994 1995 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 Cumulative R/3 installations and users SAP Sales and Profits

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started