Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

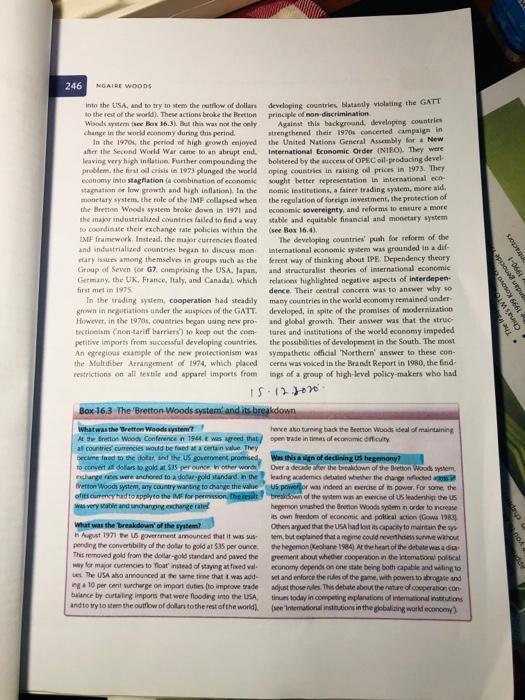

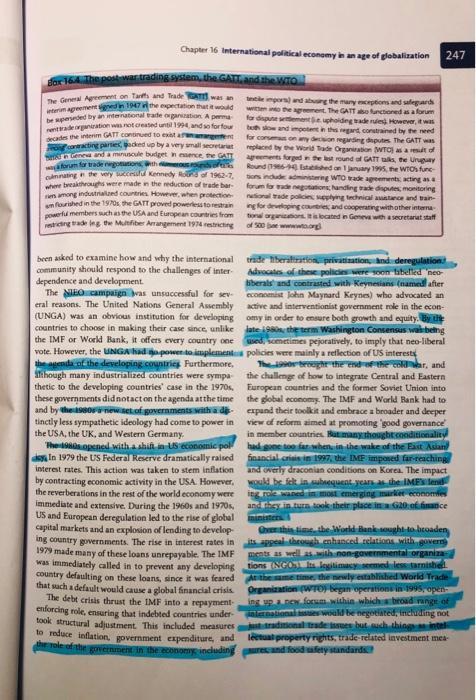

Questions 1 To what extent and why did the Bretton Woods framework for the post-war economy break down? 2 Are there any issues on