QUESTIONS:

- What sources of venture capital did Oxford Instruments consider and which source did it ultimately opt for? (5)

- What is the name usually given to high net-worth individuals who invest in new ventures, especially ones that take the form of technology-based companies? (4)

- What innovation did Oxford Instruments develop? (2)

- What kind of entrepreneur would you classify Martin Wood as? (4)

- What aspects of Martin Woods previous work experience proved helpful in founding Oxford Instruments and why? (5)

- What institutional support did Oxford Instruments get in the early years and from whom? (8)

- What instances of financial bootstrapping can you identify in this case? (4)

- How important do you consider Martin Woods personal network to have been in the success of this venture? (7)

- Which organisation was Oxford Instruments parent and to what extent did the company continue to maintain links with it? (4)

- What other problems besides funding did Oxford Instruments face as it grew and why are these sorts of problems likely to be particularly significant for technical entrepreneurs? (7)

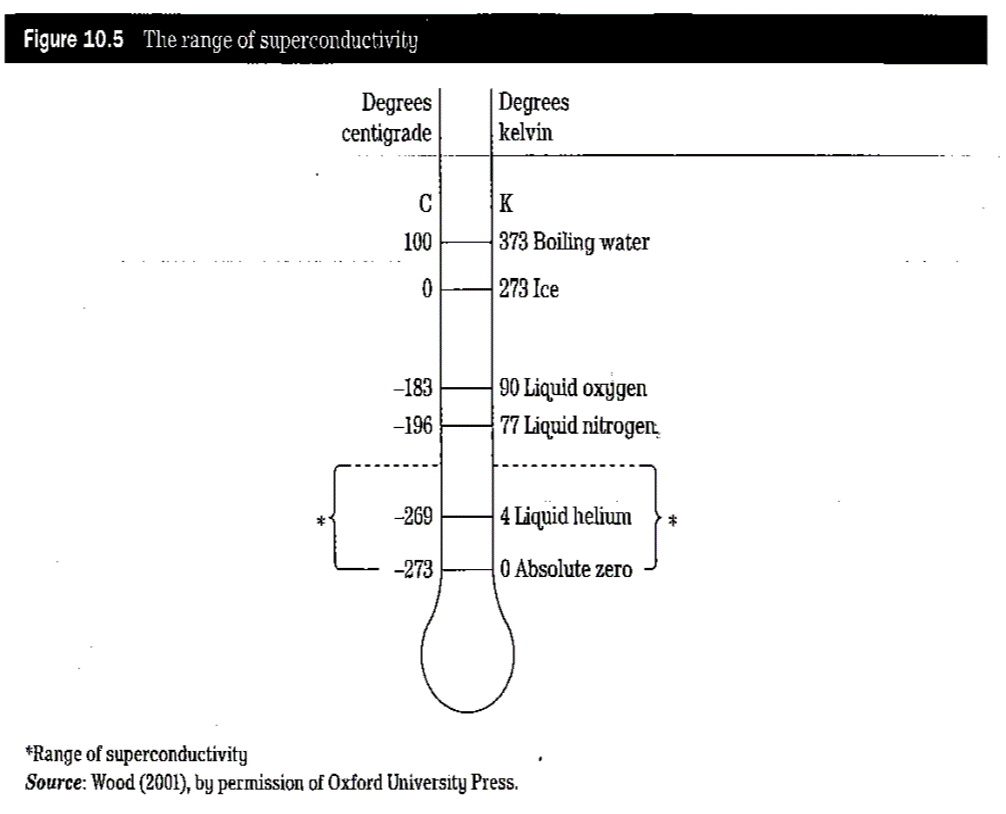

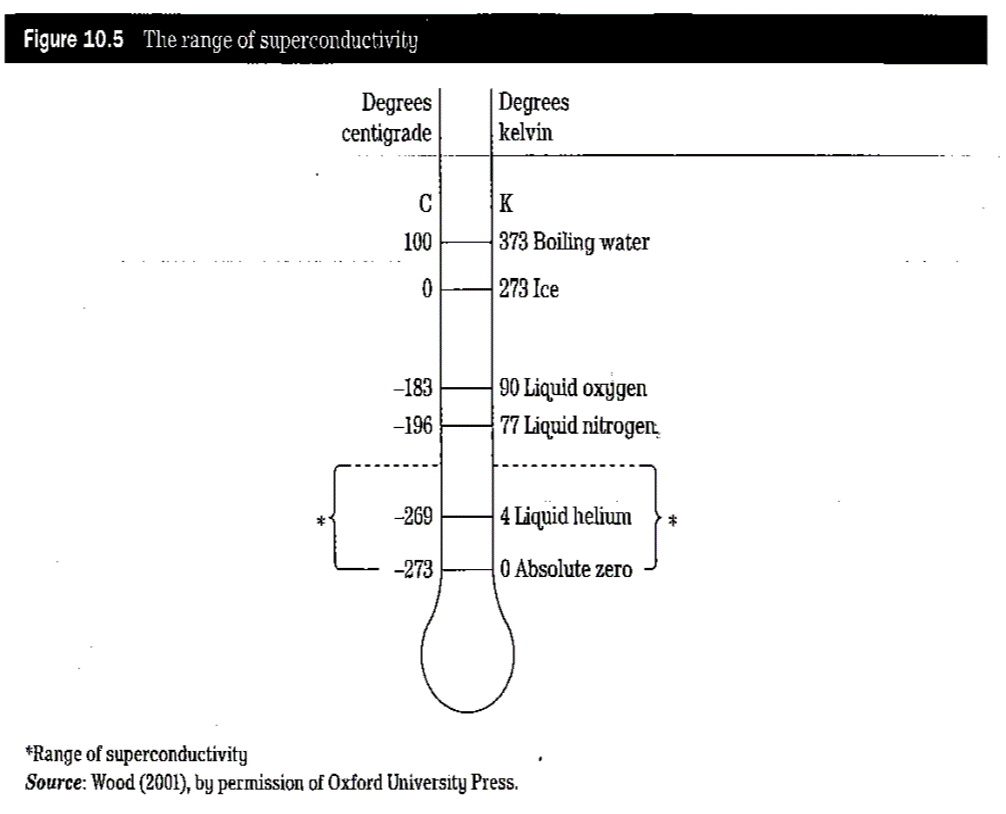

magnets because they could not ensure a reliable supply of liquid helium to enable them to operate the magnets. So it was that 0x ford Instruments undertook a major new investment, purchasing a helium liquefier from the US. It cost $35,000, a great deal more than the total investment in the company to date. The company was able to finance the purchase by extending its overdraft with the bank, supported by suitable guarantees from members of Martin Wood's family. A separate company was formed, Oxford Cryogenics, and additional premises were acquired to house the new equipment, in the form of a disused laundry rented from 0xfordshire County Council on a temporary-basis pending planning decisions in the area. Oxford Cryogenics was soon supplying laboratories across the country and the new service gave a major boost to low-temperature research in the UK. Meanwhile 0xford Instruments was growing fast. Production of both types of magnet was expanding and the following year the company moved to new and larger premises by the river Thames in 0xford. Three years after it had been formally registered, the company's annual turnover was 41,000 on which the company made a net profit of 2,460, representing a return of some 6 per cent. By this point 0x ford Instruments had 25 employees almost all of whom were Although they came very close to agreeing a deal on several occasions throughout this period, the terms were never quite right. Eventually the venture capital firm 3i put in substantial loans and equity finance. This involved 31 purchasing 20 per cent of the equity of 0 xford Instruments for 45,000, while at the same time providing a similar sum in debentures (loan finance). With adequate capital 0x ford Instruments continued to grow rapidly. Martin Wood finally quit his job at Oxford University. By this time the company had 105 staff on the payroll and the following year turnover reached $350,000. It was a small company no longer. Ficure 10.5 The rancre of sunerconductivitu Funding development of the company Although growing fast the company did not yet need outside finance. Overheads were still low and the operation sufficiently small for costs not to get out of hand. The limited finance that was needed could be provided by the Woods themselves, supplemented by loans from family members and an overdraft from the bank. One problem that the company did face at this point in its development was obtaining reliable supplies of raw materials. Liquid helium was a particular problem. Their supplier, British 0xygen Company (BOC), would not deliver supplies of the gas - so the vacuum flasks containing the gas had to go by train, resulting in delays and losses of gas due to heat and vibration. Not only was this making manufacturing difficult, it was deterring potential users of superconducting Case Study: Oxford Instruments Formation of the company Oxford Instruments was started by Martin Wood and his wife Audrey. Martin Wood came from a solid, middle-class professional family. Required to do three years' national service before going to university, Martin Wood opted to do his national service working in the coal mines of South Wales instead of going into the army. He then gained a BSc from Imperial College, London and an MA in Engineering from Cambridge. Having finished his studies, he decided to pursue a career in industry working initially as a management trainee for the National Coal Board. However, he became frustrated with working for such a large organisation, decided to look around for something else and got a job as Senior Research Officer at the Clarendon Laboratory, part of Oxford University's physics department. It was while he was working at the Clarendon Laboratory that he founded Oxford Instruments. In fact, the company began very much as a part-time venture, with Martin Wood continuing his work at the university, for a further ten years. To begin with, the work of the new venture was all concerned with design and consultancy. This was a time when the university system in the UK was expanding and Martin Wood initially assisted and advised new departments on the equipping of laboratories. Since it did not actually make anything, Oxford Instruments did not need any premises. Most of the work came through Martin Wood's contacts at the Clarendon Laboratory. In time Martin Wood and his wife Audrey came to realise that some of his customers, especially those in public research laboratories, such as the Royal Radar Establishment (RRE) in Malvern and the Harwell Laboratory of the UK Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA), had a requirement for magnets that they were finding difficult to fulfil. As a result Oxford Instruments moved into the manufacture of magnets. The move into manufacturing required rather more in the way of assets than the design and consultancy business. The need for premises was met by the Woods installing a large garden shed which had once been half a post-war 'prefab' house at the bottom of their garden. For equipment the company bought an old lathe at auction and arranged to borrow Clarendon Laboratory's special machine for winding magnetic coils. Material supplies were less of a problem, because Martin Wood was dealing with the same suppliers that he dealt with regularly at the university. The company employed a retired Clarendon Laboratory technician on a part-time basis and most of the rest of the jobs were undertaken by Audrey Wood. The company delivered its first magnet, a specialist laboratory magnet, manufactured in the shed at the bottom of the garden of the Woods' North Oxford home, to the Royal Radar Establishment, and other orders soon followed. Superconductivity and magnets Now initiated into the intricacies of manufacturing, Martin Wood continued his academic work He and his wife attended an acadenic conference at Boston in the US. This was a routine event for university staff such as Wood, but the conference was to have a far from routine impact on the new company. At the conference several research groups reported research into new developments in the field of superconductivity. Superconductivity is essentially a property of certain metals which means that at very low temperatures they suddenly lose all electrical resistance. Superconductivity had been first identified in 1911, but from then until the second half of the twentieth century it remained an interesting curiosity with no practical applications. The conference raised the prospect that this might be about to change, with the development of new materials that were sufficiently versatile to be used in practical products. Since electrical resistance dramatically reduces the efficiency of materials for transmitting electricity, any material that has a low resistance (in superconducting materials resistance falls to zero) is likely to have a dramatic impact on the efficiency of transnitting electricity. This was especially important for research laboratories working with high magnetic fields. Hitherto the scope for research had been limited by the need to employ large magnets that required enormous amounts of electrical power and special water-cooling facilities. An indication of the problems posed by the use of conventional magnets can be gauged by the fact that at the time the Clarendon Laboratory at 0x ford University had one magnet which alone used 10 per cent of the city of Oxford's electricity. Such was.this.magnet's requirement. for electricity that permission liad to be souglitfirom the electricity board every time it was switched on. In essence, developments in superconductivity meant there was the prospect of a completely new generation of nagnets (and a whole host of products using magnets) that would no longer be dependent on large quantities of electrical power. While these developments offered the prospect of a new type of magnet, to develop a commercial superconducting magnet still required many obstacles to be overcome. The new superconducting materials, such as niobium zirconium (NoZr); tended to be inconsistent and unreliable. Not only that, to achieve the very low temperatures required for the material to become superconducting required a supply of liquid helium, a liquified gas that was costly and hard to obtain. Undeterred by these problems, Oxford Instruments purchased a pound of niobium zirconium wire from the US and Martin Wood set out to make Europe's first commercial superconducting magnet. Knowledge was extremely sparse. There were no books or manuals on how to manufacture a superconducting magnet. From university sources Martin Wood had access to reports and papers from academic conferences, but even though these told him a lot about the properties of the materials with which he was working, they did not focus on issues directly relevant to manufacturing. He was fortunate in being able to use 0xford University's computer to calculate the quantities of material required and to predict the new magnet's performance characteristics. With the design completed, the first magnet did not take long to build. Using liquid helium and liquid nitrogen borrowed from the Clarendon Laboratory, the new magnet was carefully tested. Much to everyone's surprise it worked perfectly, producing a magnetic field far more powerful than had previously been possible in a laboratory without major engineering, power and cooling installations. This prototype worked well and was shown and demonstrated at a variety of exhibitions and conferences. Oxford Instruments was soon talking to prospective customers and by the end of the year had had many enquiries and ten orders for the new type of magnet. Though busy manufacturing conventional magnets, Oxford Instruments developed and manufactured its first superconducting magnet, which was delivered to Birkbeck College, at the University of London. It was at this time that the company moved out of the Woods' garden shed and into a disused stable in North Oxford, rented from a local butcher. To provide additional manufacturing capacity, the company acquired and installed some redundant machine tools bought at auction, and took on its first full-time employee. Within a year the workforce had risen to four. Further equipment such as cryostats for storing liquid helium was manufactured by Clarendon Laboratory technicians working in their spare time. The need for at least some administration, covering aspects such as payroll and invoicing, personnel and selection, and the purchasing and storing of materials, was now beginning to emerge. Nor was it only a matter of routine administration, since there was also a need to plan production and schedule the delivery of materials so that deliveries were met on time. These were aspects that neither Martin Wood nor his fellow workers with their scientific backgrounds and interest in technical issues knew much about. As a study of the company noted, 'we were rather arrogant, imagining that it would not be difficult for people with a scientific training to grow a company successfully'. Oxford Instruments was fortunate that Martin Wood's wife, Audrey, was able to handle most aspects of the administrative side of the business at this time, using a second-hand caravan that served as an office