Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Ralph Stoker never thought attending his sister's Fourth of July party would turn into a life-changing event. But indeed it had. Stoker was a

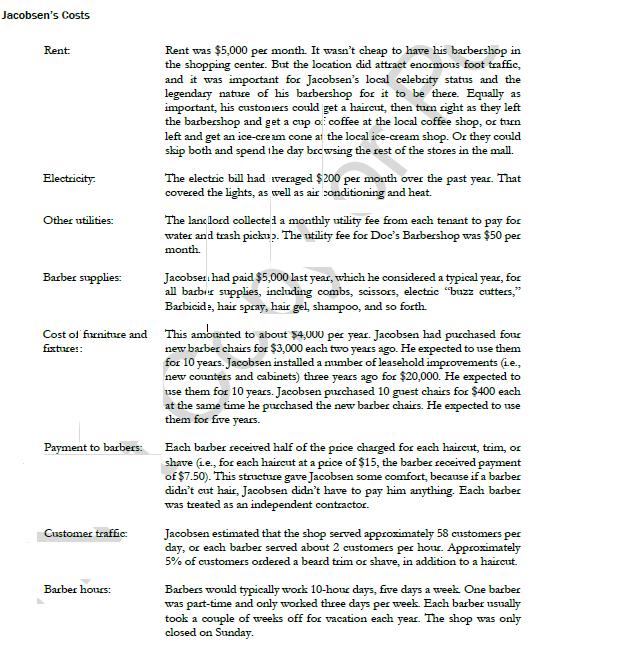

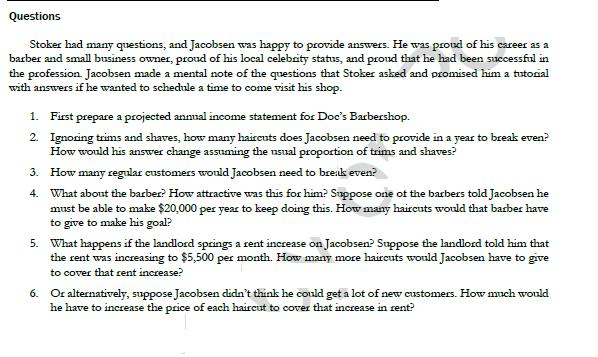

Ralph Stoker never thought attending his sister's Fourth of July party would turn into a life-changing event. But indeed it had. Stoker was a barber in Iowa City, Iowa, employed by a popular unisex salon on the north end of town. He had worked there just two years and earned a modest hourly wage along with commissions and tips. At the party, he met Donald "Doc" Jacobsen, who was in the same line of work but also happened to own a barbershop in Davenport, Iowa, about 60 miles to the east. Jacobsen's shop was a traditional old-style barbershop. It had no frills and offered only regular men's haircuts and the occasional beard trim or shave. Stoker and Jacobsen struck up a conversation about the business, and to Stoker's surprise Jacobsen offered him a job on the spot. One of Jacobsen's barbers was moving south to warmer weather, and there was an opening that Stoker could fill. Stoker was ready for a change in scenery, and the prospect of making more money in a bigger city was appealing. But the conversation meant more to Stoker than just a job offer. He was impressed that Jacobsen had been in business all these years, and even more impressed that he had made so much money in the process. Jacobsen shared with him the basics of running and managing a traditional men's barbershop. Stoker thought the traditional barbershop was a relic of the past, but Jacobsen convinced him otherwise. "If you do it right, it's a money-maker, Stoker," said Jacobsen. "I've been doing this for four decades now, and it's supported me all the way through. You could do it yourself, you know." Stoker was intrigued. During his afternoon conversation with Jacobsen he learned most of what it would take financially to open his own shop. With a small loan he could be on his way. He was certainly ready to make a move but first had a decision to make: Work for Jacobsen? Or open his own barbershop in a town of his choosing? Background There was once a golden age for barbershops in the United States. These were places most men frequented to get a peric dic straight-razor shave or haircut, of course, but also to socialize and relax. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the investments in a successful barbershop were not trivial: leather barber chairs, carved wood cabinetry, marble counters, artistic mirrors, and even light food and drink service were the norm. Premium prices could easily be charged. Because straight-razor shaves and beard waxing were more time-consuming, higher prices for these services were expected. Along with technological advances and changing social norms, the industry began to transform. Handheld disposable razors and home trimming kits became mass-produced. Men could now manage their hair care from home. During recessionary times the discretionary shaving expenditure was often the first to be cut from budgets, and customers would go longer periods between haircuts. Prices could not keep up, and most of the local barbershops were forced to simplify and provide the basic staple of a quick haircut at a reasonable price. Jacobsen opened Doc's Barbershop in 1975, after this industry transformation had taken hold. He began business in a shopping center in the heart of Davenport and had been there ever since. Initially, he was just one of several barbershops in town. Over time, though, as the barbershop model continued to lose luster, giving way to the franchised operations and unisex hair salons, competition from traditional barbershops began to fade; however, Jacobsen was not deterred because he knew there would always be a segment of the local population that wanted a simple haircut in a familiar, friendly atmosphere. And there was something about Doc's shop-it remained a business with an old-fashioned atmosphere one walked in and immediately felt at home, and for a half hour or so, forgot about what was going on outside. Now, more than 40 years later, Jacobsen had become something of a local celebrity, and his barbershop something of an historic Davenport landmark. The shop didn't take appointments, although most of its customers were regulars. Virtually all were men. The typical customer came in on average about once a month for a haircut, and didn't mind if he had a little wait. After all, Doc's reputation for quality, fair prices, and good cheer kept them coming back. The shop welcomed walk-in business from any customer; one did not have to be a regular to get a haircut at Doc's. Anyone who walked through the door was immediately made to feel welcome and encouraged to join the conversation. When seated in the chair, there was no escaping the lively banter with any of Doc's barbers. They all wanted to know a little bit about everyone that came into the shop. When a customer left, he always felt as if he had spent time with friends. Jacobsen employed a total of four barbers including himself. The barbers had become Jacobsen's trusted friends, and each worked either part- or full-time. Two had taken up barbering upon retirement from their earlier careers. Having gotten their hair cut at Doc's for years, they were attracted to the comradery of the barbershop, the ongoing interaction with the local townspeople, and the opportunity to stay busy in retirement. The others had made barbering their chosen profession right out of high school, taking the requisite coursework at the local community college to become certified and licensed barbers. All four barbers truly enjoyed going to work every day. Where else could vou get paid to spend time with those people you enjoyed being around the most? Barbershop Financials Stoker listened very carefully as he considered his options. Jacobsen was not willing to disclose exactly how much he took home as owner, but he did share that the shop had a good flow of customers all day long, except for early afternoon. He charged $15 for each haircut, regardless of the style of the cut. The only special services he offered were custom cuts (e.g., razoring a pattern in a crew cut), beard trims, and shaves. Custom cuts were rare, and prices were negotiated, while about 5% of customers received either a beard trim or shave. These were $10 each. He split the retail price of any service offered by the shop 50-50 with the barbers. Although some customers just paid the $15 for the cut and didn't tip the barber, many customers liked to "round up" and tipped as much as $5 per cut; Jacobsen figured the barbers made an average tip of about 20% or $3 per cut. Not bad, thought Stoker. Jacobsen incurred several costs in keeping his shop running. While easy enough to get one's hands around and understand, these costs couldn't be ignored. They were large enough to be attentive to, and Jacobsen had to make sure he was generating enough revenues to cover them all. "You can't stay in business if you don't make a profit," he said. Jacobsen's Costs Rent: Electricity. Other utilities: Barber supplies: Cost of furniture and fixtures: Payment to barbers: Customer traffic: Barber hours: Rent was $5,000 per month. It wasn't cheap to have his barbershop in the shopping center. But the location did attract enormous foot traffic, and it was important for Jacobsen's local celebrity status and the legendary nature of his barbershop for it to be there. Equally as important, his custoniers could get a haircut, then turn right as they left the barbershop and get a cup of coffee at the local coffee shop, or turn left and get an ice-cream cone at the local ice-cream shop. Or they could skip both and spend the day browsing the rest of the stores in the mall. The electric bill had veraged $200 per month over the past year. That covered the lights, as well as air conditioning and heat. The landlord collected a monthly utility fee from each tenant to pay for water and trash pickup. The utility fee for Doc's Barbershop was $50 per month. Jacobsen had paid $5,000 last year, which he considered a typical year, for all barber supplies, including combs, scissors, electric "buzz cutters," Barbicida, hair spray, hair gel, shampoo, and so forth. This amounted to about $4,000 per year. Jacobsen had purchased four new barber chairs for $3,000 each two years ago. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen installed a number of leasehold improvements (ie., new counters and cabinets) three years ago for $20,000. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen purchased 10 guest chairs for $400 each at the same time he purchased the new barber chairs. He expected to use them for five years. Each barber received half of the price charged for each haircut, trim, or shave (1.e., for each haircut at a price of $15, the barber received payment of $7.50). This structure gave Jacobsen some comfort, because if a barber didn't cut hair, Jacobsen didn't have to pay him anything. Each barber was treated as an independent contractor. Jacobsen estimated that the shop served approximately 58 customers per day, or each barber served about 2 customers per hour. Approximately 5% of customers ordered a beard trim or shave, in addition to a haircut. Barbers would typically work 10-hour days, five days a week. One barber was part-time and only worked three days per week. Each barber usually took a couple of weeks off for vacation each year. The shop was only closed on Sunday. Questions Stoker had many questions, and Jacobsen was happy to provide answers. He was proud of his career as a barber and small business owner, proud of his local celebrity status, and proud that he had been successful in the profession. Jacobsen made a mental note of the questions that Stoker asked and promised him a tutorial with answers if he wanted to schedule a time to come visit his shop. 1. First prepare a projected annual income statement for Doc's Barbershop. 2. Ignoring trims and shaves, how many haircuts does Jacobsen need to provide in a year to break even? How would his answer change assuming the usual proportion of trims and shaves? How many regular customers would Jacobsen need to break even? 3. 4. What about the barber? How attractive was this for him? Suppose one of the barbers told Jacobsen he must be able to make $20,000 per year to keep doing this. How many haircuts would that barber have to give to make his goal? 5. What happens if the landlord springs a rent increase on Jacobsen? Suppose the landlord told him that the rent was increasing to $5,500 per month. How many more haircuts would Jacobsen have to give to cover that rent increase? 6. Or alternatively, suppose Jacobsen didn't think he could get a lot of new customers. How much would he have to increase the price of each haircut to cover that increase in rent? Ralph Stoker never thought attending his sister's Fourth of July party would turn into a life-changing event. But indeed it had. Stoker was a barber in Iowa City, Iowa, employed by a popular unisex salon on the north end of town. He had worked there just two years and earned a modest hourly wage along with commissions and tips. At the party, he met Donald "Doc" Jacobsen, who was in the same line of work but also happened to own a barbershop in Davenport, Iowa, about 60 miles to the east. Jacobsen's shop was a traditional old-style barbershop. It had no frills and offered only regular men's haircuts and the occasional beard trim or shave. Stoker and Jacobsen struck up a conversation about the business, and to Stoker's surprise Jacobsen offered him a job on the spot. One of Jacobsen's barbers was moving south to warmer weather, and there was an opening that Stoker could fill. Stoker was ready for a change in scenery, and the prospect of making more money in a bigger city was appealing. But the conversation meant more to Stoker than just a job offer. He was impressed that Jacobsen had been in business all these years, and even more impressed that he had made so much money in the process. Jacobsen shared with him the basics of running and managing a traditional men's barbershop. Stoker thought the traditional barbershop was a relic of the past, but Jacobsen convinced him otherwise. "If you do it right, it's a money-maker, Stoker," said Jacobsen. "I've been doing this for four decades now, and it's supported me all the way through. You could do it yourself, you know." Stoker was intrigued. During his afternoon conversation with Jacobsen he learned most of what it would take financially to open his own shop. With a small loan he could be on his way. He was certainly ready to make a move but first had a decision to make: Work for Jacobsen? Or open his own barbershop in a town of his choosing? Background There was once a golden age for barbershops in the United States. These were places most men frequented to get a peric dic straight-razor shave or haircut, of course, but also to socialize and relax. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the investments in a successful barbershop were not trivial: leather barber chairs, carved wood cabinetry, marble counters, artistic mirrors, and even light food and drink service were the norm. Premium prices could easily be charged. Because straight-razor shaves and beard waxing were more time-consuming, higher prices for these services were expected. Along with technological advances and changing social norms, the industry began to transform. Handheld disposable razors and home trimming kits became mass-produced. Men could now manage their hair care from home. During recessionary times the discretionary shaving expenditure was often the first to be cut from budgets, and customers would go longer periods between haircuts. Prices could not keep up, and most of the local barbershops were forced to simplify and provide the basic staple of a quick haircut at a reasonable price. Jacobsen opened Doc's Barbershop in 1975, after this industry transformation had taken hold. He began business in a shopping center in the heart of Davenport and had been there ever since. Initially, he was just one of several barbershops in town. Over time, though, as the barbershop model continued to lose luster, giving way to the franchised operations and unisex hair salons, competition from traditional barbershops began to fade; however, Jacobsen was not deterred because he knew there would always be a segment of the local population that wanted a simple haircut in a familiar, friendly atmosphere. And there was something about Doc's shop-it remained a business with an old-fashioned atmosphere one walked in and immediately felt at home, and for a half hour or so, forgot about what was going on outside. Now, more than 40 years later, Jacobsen had become something of a local celebrity, and his barbershop something of an historic Davenport landmark. The shop didn't take appointments, although most of its customers were regulars. Virtually all were men. The typical customer came in on average about once a month for a haircut, and didn't mind if he had a little wait. After all, Doc's reputation for quality, fair prices, and good cheer kept them coming back. The shop welcomed walk-in business from any customer; one did not have to be a regular to get a haircut at Doc's. Anyone who walked through the door was immediately made to feel welcome and encouraged to join the conversation. When seated in the chair, there was no escaping the lively banter with any of Doc's barbers. They all wanted to know a little bit about everyone that came into the shop. When a customer left, he always felt as if he had spent time with friends. Jacobsen employed a total of four barbers including himself. The barbers had become Jacobsen's trusted friends, and each worked either part- or full-time. Two had taken up barbering upon retirement from their earlier careers. Having gotten their hair cut at Doc's for years, they were attracted to the comradery of the barbershop, the ongoing interaction with the local townspeople, and the opportunity to stay busy in retirement. The others had made barbering their chosen profession right out of high school, taking the requisite coursework at the local community college to become certified and licensed barbers. All four barbers truly enjoyed going to work every day. Where else could vou get paid to spend time with those people you enjoyed being around the most? Barbershop Financials Stoker listened very carefully as he considered his options. Jacobsen was not willing to disclose exactly how much he took home as owner, but he did share that the shop had a good flow of customers all day long, except for early afternoon. He charged $15 for each haircut, regardless of the style of the cut. The only special services he offered were custom cuts (e.g., razoring a pattern in a crew cut), beard trims, and shaves. Custom cuts were rare, and prices were negotiated, while about 5% of customers received either a beard trim or shave. These were $10 each. He split the retail price of any service offered by the shop 50-50 with the barbers. Although some customers just paid the $15 for the cut and didn't tip the barber, many customers liked to "round up" and tipped as much as $5 per cut; Jacobsen figured the barbers made an average tip of about 20% or $3 per cut. Not bad, thought Stoker. Jacobsen incurred several costs in keeping his shop running. While easy enough to get one's hands around and understand, these costs couldn't be ignored. They were large enough to be attentive to, and Jacobsen had to make sure he was generating enough revenues to cover them all. "You can't stay in business if you don't make a profit," he said. Jacobsen's Costs Rent: Electricity. Other utilities: Barber supplies: Cost of furniture and fixtures: Payment to barbers: Customer traffic: Barber hours: Rent was $5,000 per month. It wasn't cheap to have his barbershop in the shopping center. But the location did attract enormous foot traffic, and it was important for Jacobsen's local celebrity status and the legendary nature of his barbershop for it to be there. Equally as important, his custoniers could get a haircut, then turn right as they left the barbershop and get a cup of coffee at the local coffee shop, or turn left and get an ice-cream cone at the local ice-cream shop. Or they could skip both and spend the day browsing the rest of the stores in the mall. The electric bill had veraged $200 per month over the past year. That covered the lights, as well as air conditioning and heat. The landlord collected a monthly utility fee from each tenant to pay for water and trash pickup. The utility fee for Doc's Barbershop was $50 per month. Jacobsen had paid $5,000 last year, which he considered a typical year, for all barber supplies, including combs, scissors, electric "buzz cutters," Barbicida, hair spray, hair gel, shampoo, and so forth. This amounted to about $4,000 per year. Jacobsen had purchased four new barber chairs for $3,000 each two years ago. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen installed a number of leasehold improvements (ie., new counters and cabinets) three years ago for $20,000. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen purchased 10 guest chairs for $400 each at the same time he purchased the new barber chairs. He expected to use them for five years. Each barber received half of the price charged for each haircut, trim, or shave (1.e., for each haircut at a price of $15, the barber received payment of $7.50). This structure gave Jacobsen some comfort, because if a barber didn't cut hair, Jacobsen didn't have to pay him anything. Each barber was treated as an independent contractor. Jacobsen estimated that the shop served approximately 58 customers per day, or each barber served about 2 customers per hour. Approximately 5% of customers ordered a beard trim or shave, in addition to a haircut. Barbers would typically work 10-hour days, five days a week. One barber was part-time and only worked three days per week. Each barber usually took a couple of weeks off for vacation each year. The shop was only closed on Sunday. Questions Stoker had many questions, and Jacobsen was happy to provide answers. He was proud of his career as a barber and small business owner, proud of his local celebrity status, and proud that he had been successful in the profession. Jacobsen made a mental note of the questions that Stoker asked and promised him a tutorial with answers if he wanted to schedule a time to come visit his shop. 1. First prepare a projected annual income statement for Doc's Barbershop. 2. Ignoring trims and shaves, how many haircuts does Jacobsen need to provide in a year to break even? How would his answer change assuming the usual proportion of trims and shaves? How many regular customers would Jacobsen need to break even? 3. 4. What about the barber? How attractive was this for him? Suppose one of the barbers told Jacobsen he must be able to make $20,000 per year to keep doing this. How many haircuts would that barber have to give to make his goal? 5. What happens if the landlord springs a rent increase on Jacobsen? Suppose the landlord told him that the rent was increasing to $5,500 per month. How many more haircuts would Jacobsen have to give to cover that rent increase? 6. Or alternatively, suppose Jacobsen didn't think he could get a lot of new customers. How much would he have to increase the price of each haircut to cover that increase in rent? Ralph Stoker never thought attending his sister's Fourth of July party would turn into a life-changing event. But indeed it had. Stoker was a barber in Iowa City, Iowa, employed by a popular unisex salon on the north end of town. He had worked there just two years and earned a modest hourly wage along with commissions and tips. At the party, he met Donald "Doc" Jacobsen, who was in the same line of work but also happened to own a barbershop in Davenport, Iowa, about 60 miles to the east. Jacobsen's shop was a traditional old-style barbershop. It had no frills and offered only regular men's haircuts and the occasional beard trim or shave. Stoker and Jacobsen struck up a conversation about the business, and to Stoker's surprise Jacobsen offered him a job on the spot. One of Jacobsen's barbers was moving south to warmer weather, and there was an opening that Stoker could fill. Stoker was ready for a change in scenery, and the prospect of making more money in a bigger city was appealing. But the conversation meant more to Stoker than just a job offer. He was impressed that Jacobsen had been in business all these years, and even more impressed that he had made so much money in the process. Jacobsen shared with him the basics of running and managing a traditional men's barbershop. Stoker thought the traditional barbershop was a relic of the past, but Jacobsen convinced him otherwise. "If you do it right, it's a money-maker, Stoker," said Jacobsen. "I've been doing this for four decades now, and it's supported me all the way through. You could do it yourself, you know." Stoker was intrigued. During his afternoon conversation with Jacobsen he learned most of what it would take financially to open his own shop. With a small loan he could be on his way. He was certainly ready to make a move but first had a decision to make: Work for Jacobsen? Or open his own barbershop in a town of his choosing? Background There was once a golden age for barbershops in the United States. These were places most men frequented to get a peric dic straight-razor shave or haircut, of course, but also to socialize and relax. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the investments in a successful barbershop were not trivial: leather barber chairs, carved wood cabinetry, marble counters, artistic mirrors, and even light food and drink service were the norm. Premium prices could easily be charged. Because straight-razor shaves and beard waxing were more time-consuming, higher prices for these services were expected. Along with technological advances and changing social norms, the industry began to transform. Handheld disposable razors and home trimming kits became mass-produced. Men could now manage their hair care from home. During recessionary times the discretionary shaving expenditure was often the first to be cut from budgets, and customers would go longer periods between haircuts. Prices could not keep up, and most of the local barbershops were forced to simplify and provide the basic staple of a quick haircut at a reasonable price. Jacobsen opened Doc's Barbershop in 1975, after this industry transformation had taken hold. He began business in a shopping center in the heart of Davenport and had been there ever since. Initially, he was just one of several barbershops in town. Over time, though, as the barbershop model continued to lose luster, giving way to the franchised operations and unisex hair salons, competition from traditional barbershops began to fade; however, Jacobsen was not deterred because he knew there would always be a segment of the local population that wanted a simple haircut in a familiar, friendly atmosphere. And there was something about Doc's shop-it remained a business with an old-fashioned atmosphere one walked in and immediately felt at home, and for a half hour or so, forgot about what was going on outside. Now, more than 40 years later, Jacobsen had become something of a local celebrity, and his barbershop something of an historic Davenport landmark. The shop didn't take appointments, although most of its customers were regulars. Virtually all were men. The typical customer came in on average about once a month for a haircut, and didn't mind if he had a little wait. After all, Doc's reputation for quality, fair prices, and good cheer kept them coming back. The shop welcomed walk-in business from any customer; one did not have to be a regular to get a haircut at Doc's. Anyone who walked through the door was immediately made to feel welcome and encouraged to join the conversation. When seated in the chair, there was no escaping the lively banter with any of Doc's barbers. They all wanted to know a little bit about everyone that came into the shop. When a customer left, he always felt as if he had spent time with friends. Jacobsen employed a total of four barbers including himself. The barbers had become Jacobsen's trusted friends, and each worked either part- or full-time. Two had taken up barbering upon retirement from their earlier careers. Having gotten their hair cut at Doc's for years, they were attracted to the comradery of the barbershop, the ongoing interaction with the local townspeople, and the opportunity to stay busy in retirement. The others had made barbering their chosen profession right out of high school, taking the requisite coursework at the local community college to become certified and licensed barbers. All four barbers truly enjoyed going to work every day. Where else could vou get paid to spend time with those people you enjoyed being around the most? Barbershop Financials Stoker listened very carefully as he considered his options. Jacobsen was not willing to disclose exactly how much he took home as owner, but he did share that the shop had a good flow of customers all day long, except for early afternoon. He charged $15 for each haircut, regardless of the style of the cut. The only special services he offered were custom cuts (e.g., razoring a pattern in a crew cut), beard trims, and shaves. Custom cuts were rare, and prices were negotiated, while about 5% of customers received either a beard trim or shave. These were $10 each. He split the retail price of any service offered by the shop 50-50 with the barbers. Although some customers just paid the $15 for the cut and didn't tip the barber, many customers liked to "round up" and tipped as much as $5 per cut; Jacobsen figured the barbers made an average tip of about 20% or $3 per cut. Not bad, thought Stoker. Jacobsen incurred several costs in keeping his shop running. While easy enough to get one's hands around and understand, these costs couldn't be ignored. They were large enough to be attentive to, and Jacobsen had to make sure he was generating enough revenues to cover them all. "You can't stay in business if you don't make a profit," he said. Jacobsen's Costs Rent: Electricity. Other utilities: Barber supplies: Cost of furniture and fixtures: Payment to barbers: Customer traffic: Barber hours: Rent was $5,000 per month. It wasn't cheap to have his barbershop in the shopping center. But the location did attract enormous foot traffic, and it was important for Jacobsen's local celebrity status and the legendary nature of his barbershop for it to be there. Equally as important, his custoniers could get a haircut, then turn right as they left the barbershop and get a cup of coffee at the local coffee shop, or turn left and get an ice-cream cone at the local ice-cream shop. Or they could skip both and spend the day browsing the rest of the stores in the mall. The electric bill had veraged $200 per month over the past year. That covered the lights, as well as air conditioning and heat. The landlord collected a monthly utility fee from each tenant to pay for water and trash pickup. The utility fee for Doc's Barbershop was $50 per month. Jacobsen had paid $5,000 last year, which he considered a typical year, for all barber supplies, including combs, scissors, electric "buzz cutters," Barbicida, hair spray, hair gel, shampoo, and so forth. This amounted to about $4,000 per year. Jacobsen had purchased four new barber chairs for $3,000 each two years ago. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen installed a number of leasehold improvements (ie., new counters and cabinets) three years ago for $20,000. He expected to use them for 10 years. Jacobsen purchased 10 guest chairs for $400 each at the same time he purchased the new barber chairs. He expected to use them for five years. Each barber received half of the price charged for each haircut, trim, or shave (1.e., for each haircut at a price of $15, the barber received payment of $7.50). This structure gave Jacobsen some comfort, because if a barber didn't cut hair, Jacobsen didn't have to pay him anything. Each barber was treated as an independent contractor. Jacobsen estimated that the shop served approximately 58 customers per day, or each barber served about 2 customers per hour. Approximately 5% of customers ordered a beard trim or shave, in addition to a haircut. Barbers would typically work 10-hour days, five days a week. One barber was part-time and only worked three days per week. Each barber usually took a couple of weeks off for vacation each year. The shop was only closed on Sunday. Questions Stoker had many questions, and Jacobsen was happy to provide answers. He was proud of his career as a barber and small business owner, proud of his local celebrity status, and proud that he had been successful in the profession. Jacobsen made a mental note of the questions that Stoker asked and promised him a tutorial with answers if he wanted to schedule a time to come visit his shop. 1. First prepare a projected annual income statement for Doc's Barbershop. 2. Ignoring trims and shaves, how many haircuts does Jacobsen need to provide in a year to break even? How would his answer change assuming the usual proportion of trims and shaves? How many regular customers would Jacobsen need to break even? 3. 4. What about the barber? How attractive was this for him? Suppose one of the barbers told Jacobsen he must be able to make $20,000 per year to keep doing this. How many haircuts would that barber have to give to make his goal? 5. What happens if the landlord springs a rent increase on Jacobsen? Suppose the landlord told him that the rent was increasing to $5,500 per month. How many more haircuts would Jacobsen have to give to cover that rent increase? 6. Or alternatively, suppose Jacobsen didn't think he could get a lot of new customers. How much would he have to increase the price of each haircut to cover that increase in rent?

Step by Step Solution

★★★★★

3.43 Rating (150 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

First prepare a projected annual income statement for Docs Barbershop Stoker had many questions and Jacobsen was happy to provide answers He was proud of his career as a barber and small business owne...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started