Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

Read the attachment below and highlight important points in it ? THUNDERBIRD THE GARVIN SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT A03-04-0006 ARGENTINA: ANATOMY OF A FINANCIAL CRISIS

Read the attachment below and highlight important points in it ?

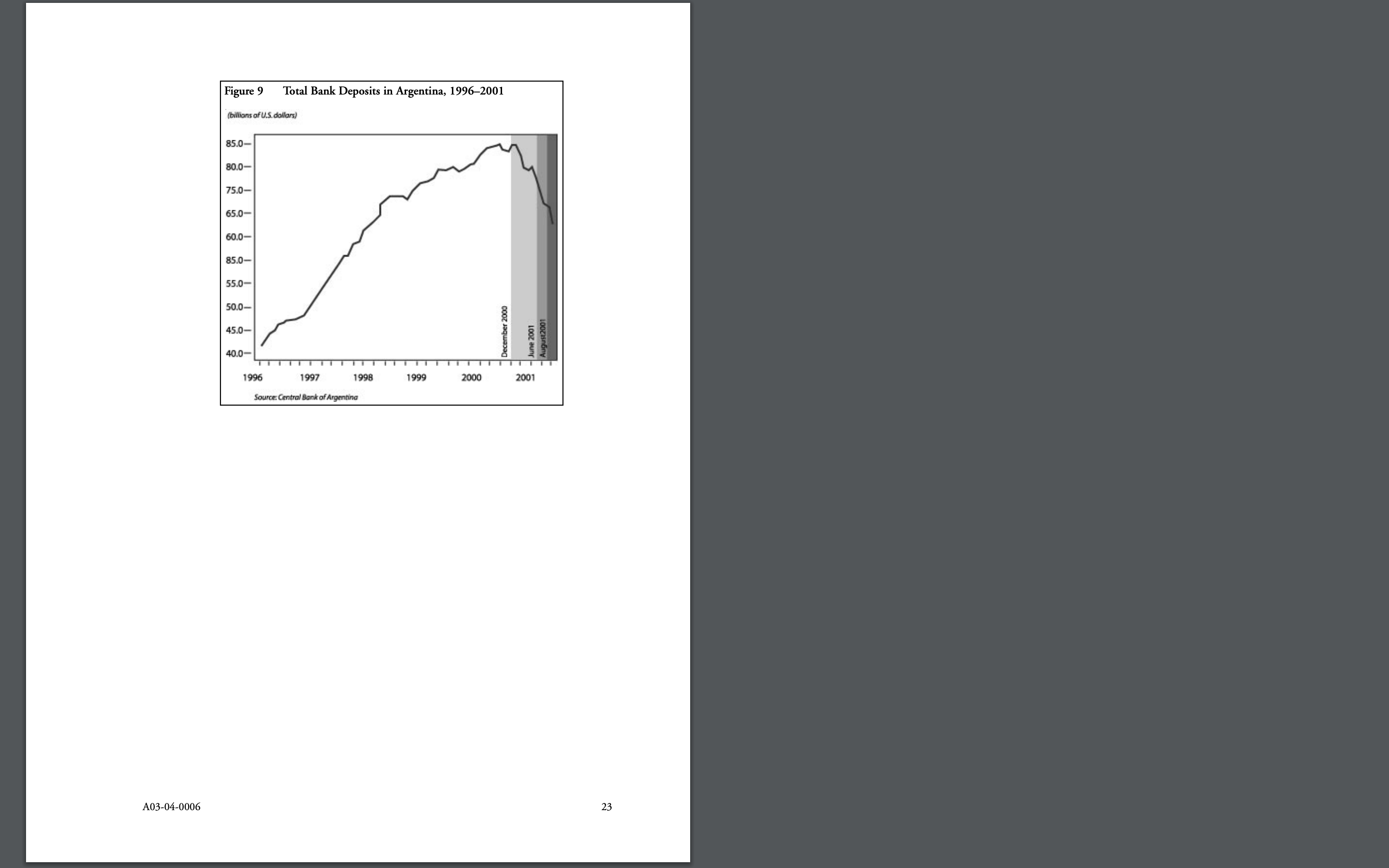

THUNDERBIRD THE GARVIN SCHOOL OF INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT A03-04-0006 ARGENTINA: ANATOMY OF A FINANCIAL CRISIS Introduction Few countries have possessed the promise, disappointment, and despair of Argentina. A country that, at the turn of the Twentieth Century, touted the highest living standards in the entire western hemisphere claimed the title of being home to the world's largest sovereign default on foreign debt ever-$132 billion which occurred in December of 2001. Since formal default, Argentina's economy has acceler- ated its downward spiral. The banking system effectively closed December 2001. When facing massive withdrawals of dollar deposits, the government authorities placed strict limits on withdrawals, which effectively confiscated Argentineans' savings and checking account deposits. Furthermore, during the first quarter of 2002, the Argentine gross domestic product (GDP) contracted a significant 16.3%. The cornerstone of Argentine economic stability since 1991, the Convertibility Plan that pegged the value of the peso to the dollar officially ended on January 6, 2002 and was replaced by a freer floating currency. Subsequently, market forces devalued the peso by 120%, representing a massive drain of wealth from the country. With this sharp devaluation, the probability of a repeat episode of hyperin- flation, prevalent in Argentina's past, was quite high. Moreover, this would bankrupt thousands of Argentine companies and individuals whose debts were held mainly in dollars. In 2001, Argentine companies seeking court protection from creditors jumped 21% from 2000, and bankruptcy filings in December 2001 rose to record highs. Internationally, investors began to soberly recognize the magnitude of their potential losses. An analyst at Commerzbank in New York commented, Definitely, investors need to mark their recovery value assumptions down." He had recently marked his recovery potential at 20 cents to the U.S. dollar. Argentineans' per-capita income became one of the lowest in all of Latin America, and more than one- third of its population lived below the poverty line. Argentina's traditional trading partners in Mercosur were feeling the pain as well. Argentina absorbed 9% of Brazil's exports and, by 2002, the country's importers were already delinquent in the amount of US$1.2 billion in their payments for these goods. According to Joao Malandrin, financial director at Sadia, Brazil's largest pork and poultry producer, "Without the possibility of a mechanism by which we can receive payment immediately in hard cur- rency or up front, it's complicated to continue selling to Argentina."2 With little sign of contagion to the crisis, Washington was uninterested in organizing a rescue package similar what had been done for Mexico during the peso crisis of 1994-95. The White House simply restated its position that Argentina should work with the International Monetary Fund (IMF or Fund) to develop a sustainable economic program. Beyond that, in an interview with Bloomberg News, the U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Paul O'Neill, only asked, "Are they going to do anything about the relationship between the federal government and the provinces?" He was referring to a long-held posi- See Angela Pruitt, "Haircut Keeps Getting Steeper for Argentina Bondholders," Dow Jones Emerging Markets Report, 10 January 2002. 2 Katherine Baldwin, "Argentine Cash Crunch Imperils Brazil Exports, "Reuters News, 11 January 2002. Copyright 2004 Thunderbird, The Garvin School of International Management. All rights reserved. This case was prepared by Professor C. Roe Goddard, with the assistance of Brett Karcher, for the purpose of classroom discussion only, and not to indicate either effective or ineffective management. tion in Washington that a structural flaw in the Argentine political system allowed provinces to spend money and take on debt while the federal government was responsible for generating revenues to pay for those expenditures. Clearly, this was a prescription for irresponsibility and Washington recognized it. Confidence in elected officials was virtually nonexistent. In two month's time, December 2001- January 2002, Argentina had five presidents, none of whom were capable of restoring political or eco- nomic stability to this country of 36 million people. Street riots in December took 28 lives. In mid- January, more than 10,000 middle-class Argentineans and businessmen protested in front of the presi- dential palace, unhappy with the freeze on bank accounts and the deepening economic downturn. Many shouted "Get out! Get out!" and in reference to government officials, "They're all thieves." Un- employment as of December 2001 was 18% and rising. With few job prospects, long lines of Argentineans formed around European embassies in Buenos Aires, seeking to emigrate. One middle-class business- man in Buenos Aires commented, "You fight all your life to build something, only to see it come crashing down around you because the country you live in doesn't work. We work as hard, if not harder than people anywhere in the world; we have dreams for our children; we have hopes of owning property and building a life. Now, to suffer this at my age is too much. I have lost faith. My advice to my children is to leave here, emigrate abroad. I would if I could."4 There was simply no precedent in the entire history of Latin America for the degree of political, economic, and social implosion Argentina experienced in the month following its sovereign debt de- fault in December 2001. But how and why did this happen? In the period leading up to the depegging of the peso and formal default in December, the IMF had been integrally involved in assisting and advising Argentina on the macroeconomic management of its economy. The Fund, arguably, possessed the world's largest and most well-trained pool of international economists and public policy specialists. Furthermore, Argentina, among all of the emerging market borrowers from the IMF, had been the poster child for pursuing sound macroeconomic policies and debt management. From 1992 until Septem- ber 7, 2001, just three months prior to the December default, when the IMF augmented its March 10, 2000 agreement and increased its lending commitment by an additional $7.2 billion, Argentina was under four successive financing arrangements, yielding virtually continuous close supervision. These four financing arrangements, along with their conditions, included two Extended Fund Facilities (EFFs) approved in 1992 and 1998, and two Standby Arrangements (SBAs) approved in 1996 and 2000. In these roughly ten years, Argentina experienced a steady rise in its balance of outstanding credit to the IMF. The IMF advised Argentina over this 10-year period on fiscal, monetary, and banking matters (the IMF's presumed forte), and dispatched approximately 50 missions between 1991 and 2002. So, the puzzling question remains: how and why did the financial crisis of December 2001/January 2002 happen? Center of the Storm: Private Capital Flows and the Emerging Markets In an ideal world, domestic economies, and the trade and financial exchanges among them, would run uninterrupted and smoothly. Domestic economies would experience ever-expanding GDPs with non- inflationary growth; unemployment would not exist; current accounts would be in balance; tax rev- enues would be adequate and collectable; and governments would achieve their social and economic objectives with no need to run fiscal deficits. Financial capital would be smoothly and effectively inter- mediated from those with excess to those in need. In the private sector, bankruptcies would be at an acceptable level, reflecting the natural evolution of the economy and the culling of unproductive activity. Firms would have manageable debt-to-equity 3 Paul Bluestein and Anthony Faiola, "Argentina Told of Conditions for Aid; IMF, O'Neill Urge Free-Floating Peso, Action to Curb Inflation and Spending," The Washington Post, 10 January 2002. 4 Anthony Faiola, "Argentine Family Sees Devaluation as Financial Ruin; Peso's Decline Could Devastate Country," The Washington Post, 4 January 2002. 2 A03-04-0006

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Here are the important points in the document titled Argentina Anatomy of a Financial Crisis by Thunderbird The Garvin School of International Managem...

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started