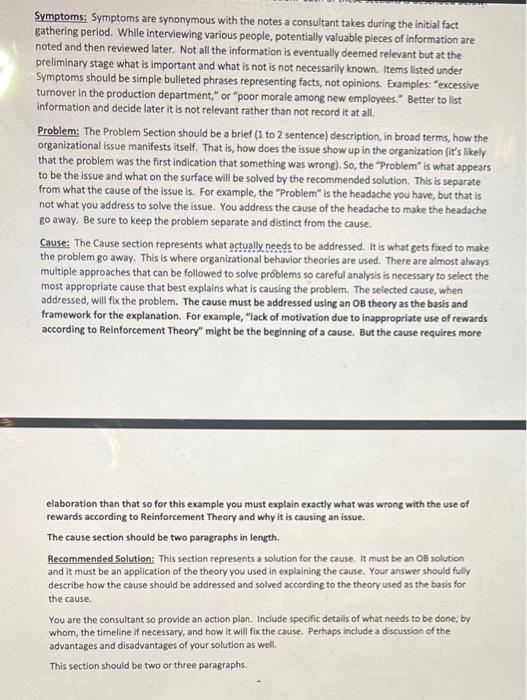

Spanglemaker Publishing For nearly twenty-five years, Marty Callahan had been the executive editor at Spanglemaker Publishing, a small company that specialized in children's books. Although Marty had had a long and happy career at Spanglemaker, he was headed for semi-retirement The president of Spanglemaker, Lawrence Guthrie, had recently announced that the company planned a much more aggressive marketing strategy. Noting that a successful children's book - such as Chris Van Allsburgh's The Polar Express - could be on best-seller lists for years, whereas adult literature had a much shorter life span for high-volume sales, Guthrie had decided to produce more innovative children's books in hopes of discovering an occasional long-term "cash cow." While Marty understood Guthrie's rationale, he decided that the new goals and directions of the company were not consistent with his interests and that it was time to leave. Marty had always enjoyed the friendly atmosphere of Spanglemaker - how people would clip cartoons for him and how he and some of his colleagues would have long lunches in a nearby park, swapping book tips and jokes. As a sixty-two-year-old widower whose children had moved out of state, these get-togethers had become important to him. Although Guthrie had said nothing directly, Marty realized that his boss's new expectations for the executive editor would mean a faster pace that would leave little time for friendly chats. Guthrie had hinted that Marty could step down and again become a copy editor, a move that would allow him to continue his long lunches and coffee breaks. But, at his age, Marty decided to do freelance work at home for a variety of large and small publishing companies. It wouldn't be hard to get enough business; over the years, Marty had made many connections, and he was well liked and respected in the industry. In a short meeting, Marty told Guthrie of his decision to take cariy retirement. Guthrie wished him luck and asked him if, before leaving, he would recommend someone to take his place. Three Spanglemaker copy editors had expressed interest in the job. It would be a sensitive decision: each candidate had a great deal of experience and was confident that he or she would be the best choice. Initially, Marty eliminated Charles Langley from the list of candidates. Though they were good friends, Marty was sur that Charles would be obsessed with being in charge of his workers. Although he had more experience and seniority than the other two candidates, Charles would certainly be a big "rule maker" who might alienate the workers. He was bright and one of the better copy editors, and his people had the reputation of being highly productive. Charles was known to be hardworking and to expect nothing less from those who worked under him. The maximum stay at Spanglemaker for most people who worked for Charles seemed to be about two years, considerably less than the company average. After getting some really good training from him, the people who worked for Charles generally left to take higher-paying jobs with competitors. When Spanglemaker executives offered to match what competitors were offering, as an enticement to stay, few accepted. Having a fairly constant string of new employees meant a lot of fresh and new ideas, although Charles insisted that his people master the basics before getting involved in innovation. of the other two candidates, Marty decided to first interview Dominique Bernays, who had been with the company for more than ten years. In the past, Marty had been a reluctant admirer of Dominique's. She had shown a knack for discovering new authors and working with them. Many of her projects were unconventional but successful. For example, she had done well in helping an author develop a book for young children - a story about a little girl who had a single mother. Dominique believed that Spanglemaker should publish books geared toward the children of single parents, house-husbands, and even gay parents. Marty wasn't sure that the world was ready for such things. Marty was also concerned that Dominique's personality would be problematic. He found her to be - well - "pushy." She was always deadly serious about her job and never seemed to have time for a friendly word. At work, she mostly stayed in her office, just chuckling and continuing to work even when someone told her she needed a breather. "Tell me why you should get the job," Marty said during the interview. "I think my record shows that I thrive on responsibility," Dominique replied, staring into Marty's eyes so hard that it made him uncomfortable. "As you know, most of the books that I've been involved with have been recognized by the critics as real breakthroughs in children's literature, such as the bilingual books for Hispanig families. Given my performance over the last several years at Spanglemaker, I feel I deserve an opportunity to grow while the company grows." "Your individual performance has been outstanding." Marty admitted. "But how would you manage the copy editors?" Dominique gave him a hard glance, and Marty wondered if he had sounded more skeptical than he had intended. But why not? He had legitimate doubts about her interpersonal skills. "As executive editor, I would do several things differently," she began. "First, rather than just assigning to people to an author, I would let them choose the projects that they would find most interesting. If a copy editor prefers to do primarily realistic fiction, or fantasy, or whatever, I'd let them do it whenever possible. At the same time, I would work closely with the copy editors so that I would always know what they are working on. If someone did a particularly good job, I would reward him or her - you know, a plaque for the office, his or her name displayed somewhere - or maybe just an occasional day off for anyone who doesn't seem comfortable about being publicly congratulated. Most importantly, though, I would emphasize that Spanglemaker should produce the best books possible - whatever it takes, I'll make sure that we publish the most dynamic books." "As you know, sometimes the executive editor has to deal with support staff - temporary secretaries, receptionists, and various others - people who tend to be unmotivated. How would you deal with that?" Marty asked. "It would really depend on the situation," she replied. I think some people work fine without much input from a boss, while others are basically lazy and have to be ordered around if you want anything to get done." Would Dominique be a tough, single-minded slave driver if she became boss? Marty couldn't be sure. Next, Marty interviewed Lou Healy, another veteran employee of Spanglemaker. For twelve years, Lou had done more than work for Marty. He had frequently joined him for lunch, and they had even attended poetry readings and wine-and-cheese book signings together. Nonetheless, Marty was determined to be all business in this interview. He wanted to be fair and make the best possible decision for the company. "Why should you become executive editor?" Marty asked. Lou spoke in his usual relaxed and confident voice. "I believe that, above all, a manager of workers should be a "people person," much like the way you, Marty, have been over the years. I get along with almost everyone here, as you know. I don't think I've had a single argument in all the years that I've been here." Marty knew this was true, and his sentiment was even reflected in the kind of children's books with which Lou preferred to work. He liked books that were traditional, even nostalgic - warm stories about girls who owned horses, or realistic novels that supported the idea of family togetherness. "What kind of manager would you be?" Marty asked. I would supervise everyone closely," Lou responded, "but in a friendly way. I believe that a close relationship between a boss and his workers is what motivates these workers to be the best they can be. Under no circumstances would I yell at an employee or lower the boom on anyone. People basically want to do a good job. A manager should be a positive thinker and be supportive to help them do that kind of job." Marty and Lou shook hands, and Lou left. Sitting alone amid the bookshelves in his office, Marty pondered the decision. He had to admit that Dominique had some interesting ideas that might prove to be effective - letting people choose their own book assignments, for example. But he still had serious concerns about her ability to get along with others. It seemed as if work was the only thing that mattered to her: Wouldn't the other copy editors find her to be too "gung ho?" He knew that Lou wouldn't like her as a boss. And what would Charles Langley think about taking orders from a woman? On the other hand, what would happen if he chose Lou? Would Dominique be able to accept that? "Hell, I don't have a crystal ball," Marty said to himself at last. He didn't want to spend too much time making a decision. Already the pace had been picking up at Spanglemaker; the number of books in production had increase by 25 percent in the last two months. Soon the little publishing company he had loved would become a fast-paced marketing machine that would leave him in the dust. The next morning, Marty called Dominique into his office. "I'm sorry," he said, "but I'm going to recommend Lou Healy for the job." "It figures," she snapped. Uncomfortable, Marty tried to explain the importance of having a people-person as a manager and how his decision in no way meant to diminish the excellence of her performance. Her dark brown eyes stared at him in silent anger, making him stutter as he finished his explanation. "Don't think that I believe any of that," she said. "We women have had to deal with this kind of treatment for centuries." "That has nothing to do with it!" Marty insisted. "Charles has more experience and seniority than you do, and I still put you ahead of him in making my decision." With a sense of frustration, Marty realized that the last chapter of a successful career in publishing had revealed an unpleasant twist in the plot. Symptoms: Symptoms are synonymous with the notes a consultant takes during the initial fact gathering period. While interviewing various people, potentially valuable pleces of information are noted and then reviewed later. Not all the information is eventually deemed relevant but at the preliminary stage what is important and what is not is not necessarily known. Items listed under Symptoms should be simple bulleted phrases representing facts, not opinions. Examples: excessive turnover in the production department," or "poor morale among new employees." Better to list information and decide later it is not relevant rather than not record it at all. Problem: The Problem Section should be a brief (1 to 2 sentence) description, in broad terms, how the organizational issue manifests itself. That is, how does the issue show up in the organization (it's likely that the problem was the first indication that something was wrong). So, the "Problem is what appears to be the issue and what on the surface will be solved by the recommended solution. This is separate from what the cause of the issue is. For example, the Problem" is the headache you have, but that is not what you address to solve the issue. You address the cause of the headache to make the headache go away. Be sure to keep the problem separate and distinct from the cause. Cause: The Cause section represents what actually needs to be addressed. It is what gets fixed to make the problem go away. This is where organizational behavior theories are used. There are almost always multiple approaches that can be followed to solve problems so careful analysis is necessary to select the 50 most appropriate cause that best explains what is causing the problem. The selected cause, when addressed, will fix the problem. The cause must be addressed using an OB theory as the basis and framework for the explanation. For example, "lack of motivation due to inappropriate use of rewards according to Reinforcement Theory" might be the beginning of a cause. But the cause requires more elaboration than that so for this example you must explain exactly what was wrong with the use of rewards according to Reinforcement Theory and why it is causing an issue. The cause section should be two paragraphs in length. Recommended Solution: This section represents a solution for the cause. It must be an OB solution and it must be an application of the theory you used in explaining the cause. Your answer should fully describe how the cause should be addressed and solved according to the theory used as the basis for the cause You are the consultant so provide an action plan. Include specific details of what needs to be done, by whom, the timeline if necessary, and how it will fix the cause. Perhaps include a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of your solution as well. This section should be two or three paragraphs. Spanglemaker Publishing For nearly twenty-five years, Marty Callahan had been the executive editor at Spanglemaker Publishing, a small company that specialized in children's books. Although Marty had had a long and happy career at Spanglemaker, he was headed for semi-retirement The president of Spanglemaker, Lawrence Guthrie, had recently announced that the company planned a much more aggressive marketing strategy. Noting that a successful children's book - such as Chris Van Allsburgh's The Polar Express - could be on best-seller lists for years, whereas adult literature had a much shorter life span for high-volume sales, Guthrie had decided to produce more innovative children's books in hopes of discovering an occasional long-term "cash cow." While Marty understood Guthrie's rationale, he decided that the new goals and directions of the company were not consistent with his interests and that it was time to leave. Marty had always enjoyed the friendly atmosphere of Spanglemaker - how people would clip cartoons for him and how he and some of his colleagues would have long lunches in a nearby park, swapping book tips and jokes. As a sixty-two-year-old widower whose children had moved out of state, these get-togethers had become important to him. Although Guthrie had said nothing directly, Marty realized that his boss's new expectations for the executive editor would mean a faster pace that would leave little time for friendly chats. Guthrie had hinted that Marty could step down and again become a copy editor, a move that would allow him to continue his long lunches and coffee breaks. But, at his age, Marty decided to do freelance work at home for a variety of large and small publishing companies. It wouldn't be hard to get enough business; over the years, Marty had made many connections, and he was well liked and respected in the industry. In a short meeting, Marty told Guthrie of his decision to take cariy retirement. Guthrie wished him luck and asked him if, before leaving, he would recommend someone to take his place. Three Spanglemaker copy editors had expressed interest in the job. It would be a sensitive decision: each candidate had a great deal of experience and was confident that he or she would be the best choice. Initially, Marty eliminated Charles Langley from the list of candidates. Though they were good friends, Marty was sur that Charles would be obsessed with being in charge of his workers. Although he had more experience and seniority than the other two candidates, Charles would certainly be a big "rule maker" who might alienate the workers. He was bright and one of the better copy editors, and his people had the reputation of being highly productive. Charles was known to be hardworking and to expect nothing less from those who worked under him. The maximum stay at Spanglemaker for most people who worked for Charles seemed to be about two years, considerably less than the company average. After getting some really good training from him, the people who worked for Charles generally left to take higher-paying jobs with competitors. When Spanglemaker executives offered to match what competitors were offering, as an enticement to stay, few accepted. Having a fairly constant string of new employees meant a lot of fresh and new ideas, although Charles insisted that his people master the basics before getting involved in innovation. of the other two candidates, Marty decided to first interview Dominique Bernays, who had been with the company for more than ten years. In the past, Marty had been a reluctant admirer of Dominique's. She had shown a knack for discovering new authors and working with them. Many of her projects were unconventional but successful. For example, she had done well in helping an author develop a book for young children - a story about a little girl who had a single mother. Dominique believed that Spanglemaker should publish books geared toward the children of single parents, house-husbands, and even gay parents. Marty wasn't sure that the world was ready for such things. Marty was also concerned that Dominique's personality would be problematic. He found her to be - well - "pushy." She was always deadly serious about her job and never seemed to have time for a friendly word. At work, she mostly stayed in her office, just chuckling and continuing to work even when someone told her she needed a breather. "Tell me why you should get the job," Marty said during the interview. "I think my record shows that I thrive on responsibility," Dominique replied, staring into Marty's eyes so hard that it made him uncomfortable. "As you know, most of the books that I've been involved with have been recognized by the critics as real breakthroughs in children's literature, such as the bilingual books for Hispanig families. Given my performance over the last several years at Spanglemaker, I feel I deserve an opportunity to grow while the company grows." "Your individual performance has been outstanding." Marty admitted. "But how would you manage the copy editors?" Dominique gave him a hard glance, and Marty wondered if he had sounded more skeptical than he had intended. But why not? He had legitimate doubts about her interpersonal skills. "As executive editor, I would do several things differently," she began. "First, rather than just assigning to people to an author, I would let them choose the projects that they would find most interesting. If a copy editor prefers to do primarily realistic fiction, or fantasy, or whatever, I'd let them do it whenever possible. At the same time, I would work closely with the copy editors so that I would always know what they are working on. If someone did a particularly good job, I would reward him or her - you know, a plaque for the office, his or her name displayed somewhere - or maybe just an occasional day off for anyone who doesn't seem comfortable about being publicly congratulated. Most importantly, though, I would emphasize that Spanglemaker should produce the best books possible - whatever it takes, I'll make sure that we publish the most dynamic books." "As you know, sometimes the executive editor has to deal with support staff - temporary secretaries, receptionists, and various others - people who tend to be unmotivated. How would you deal with that?" Marty asked. "It would really depend on the situation," she replied. I think some people work fine without much input from a boss, while others are basically lazy and have to be ordered around if you want anything to get done." Would Dominique be a tough, single-minded slave driver if she became boss? Marty couldn't be sure. Next, Marty interviewed Lou Healy, another veteran employee of Spanglemaker. For twelve years, Lou had done more than work for Marty. He had frequently joined him for lunch, and they had even attended poetry readings and wine-and-cheese book signings together. Nonetheless, Marty was determined to be all business in this interview. He wanted to be fair and make the best possible decision for the company. "Why should you become executive editor?" Marty asked. Lou spoke in his usual relaxed and confident voice. "I believe that, above all, a manager of workers should be a "people person," much like the way you, Marty, have been over the years. I get along with almost everyone here, as you know. I don't think I've had a single argument in all the years that I've been here." Marty knew this was true, and his sentiment was even reflected in the kind of children's books with which Lou preferred to work. He liked books that were traditional, even nostalgic - warm stories about girls who owned horses, or realistic novels that supported the idea of family togetherness. "What kind of manager would you be?" Marty asked. I would supervise everyone closely," Lou responded, "but in a friendly way. I believe that a close relationship between a boss and his workers is what motivates these workers to be the best they can be. Under no circumstances would I yell at an employee or lower the boom on anyone. People basically want to do a good job. A manager should be a positive thinker and be supportive to help them do that kind of job." Marty and Lou shook hands, and Lou left. Sitting alone amid the bookshelves in his office, Marty pondered the decision. He had to admit that Dominique had some interesting ideas that might prove to be effective - letting people choose their own book assignments, for example. But he still had serious concerns about her ability to get along with others. It seemed as if work was the only thing that mattered to her: Wouldn't the other copy editors find her to be too "gung ho?" He knew that Lou wouldn't like her as a boss. And what would Charles Langley think about taking orders from a woman? On the other hand, what would happen if he chose Lou? Would Dominique be able to accept that? "Hell, I don't have a crystal ball," Marty said to himself at last. He didn't want to spend too much time making a decision. Already the pace had been picking up at Spanglemaker; the number of books in production had increase by 25 percent in the last two months. Soon the little publishing company he had loved would become a fast-paced marketing machine that would leave him in the dust. The next morning, Marty called Dominique into his office. "I'm sorry," he said, "but I'm going to recommend Lou Healy for the job." "It figures," she snapped. Uncomfortable, Marty tried to explain the importance of having a people-person as a manager and how his decision in no way meant to diminish the excellence of her performance. Her dark brown eyes stared at him in silent anger, making him stutter as he finished his explanation. "Don't think that I believe any of that," she said. "We women have had to deal with this kind of treatment for centuries." "That has nothing to do with it!" Marty insisted. "Charles has more experience and seniority than you do, and I still put you ahead of him in making my decision." With a sense of frustration, Marty realized that the last chapter of a successful career in publishing had revealed an unpleasant twist in the plot. Symptoms: Symptoms are synonymous with the notes a consultant takes during the initial fact gathering period. While interviewing various people, potentially valuable pleces of information are noted and then reviewed later. Not all the information is eventually deemed relevant but at the preliminary stage what is important and what is not is not necessarily known. Items listed under Symptoms should be simple bulleted phrases representing facts, not opinions. Examples: excessive turnover in the production department," or "poor morale among new employees." Better to list information and decide later it is not relevant rather than not record it at all. Problem: The Problem Section should be a brief (1 to 2 sentence) description, in broad terms, how the organizational issue manifests itself. That is, how does the issue show up in the organization (it's likely that the problem was the first indication that something was wrong). So, the "Problem is what appears to be the issue and what on the surface will be solved by the recommended solution. This is separate from what the cause of the issue is. For example, the Problem" is the headache you have, but that is not what you address to solve the issue. You address the cause of the headache to make the headache go away. Be sure to keep the problem separate and distinct from the cause. Cause: The Cause section represents what actually needs to be addressed. It is what gets fixed to make the problem go away. This is where organizational behavior theories are used. There are almost always multiple approaches that can be followed to solve problems so careful analysis is necessary to select the 50 most appropriate cause that best explains what is causing the problem. The selected cause, when addressed, will fix the problem. The cause must be addressed using an OB theory as the basis and framework for the explanation. For example, "lack of motivation due to inappropriate use of rewards according to Reinforcement Theory" might be the beginning of a cause. But the cause requires more elaboration than that so for this example you must explain exactly what was wrong with the use of rewards according to Reinforcement Theory and why it is causing an issue. The cause section should be two paragraphs in length. Recommended Solution: This section represents a solution for the cause. It must be an OB solution and it must be an application of the theory you used in explaining the cause. Your answer should fully describe how the cause should be addressed and solved according to the theory used as the basis for the cause You are the consultant so provide an action plan. Include specific details of what needs to be done, by whom, the timeline if necessary, and how it will fix the cause. Perhaps include a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of your solution as well. This section should be two or three paragraphs