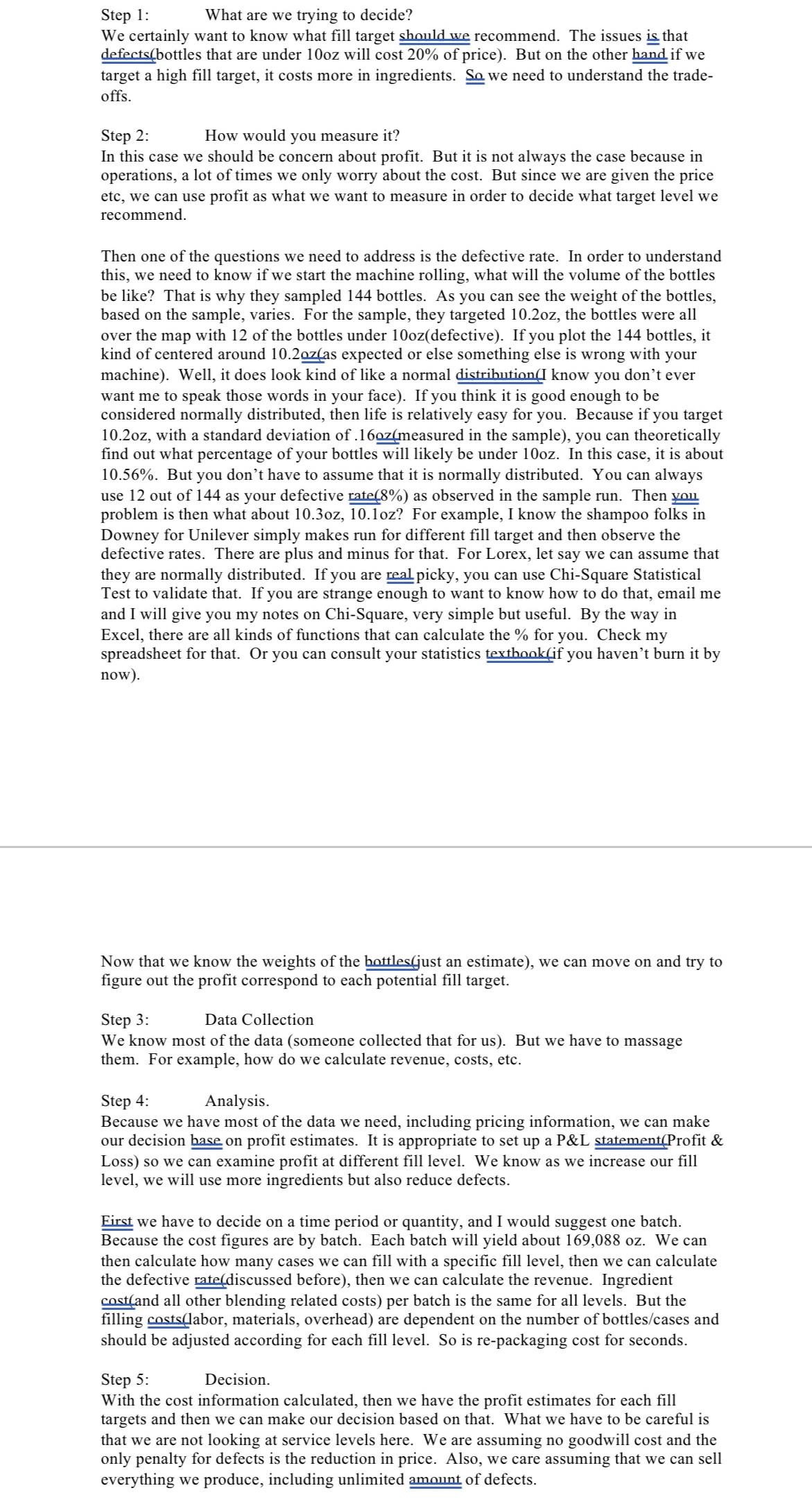

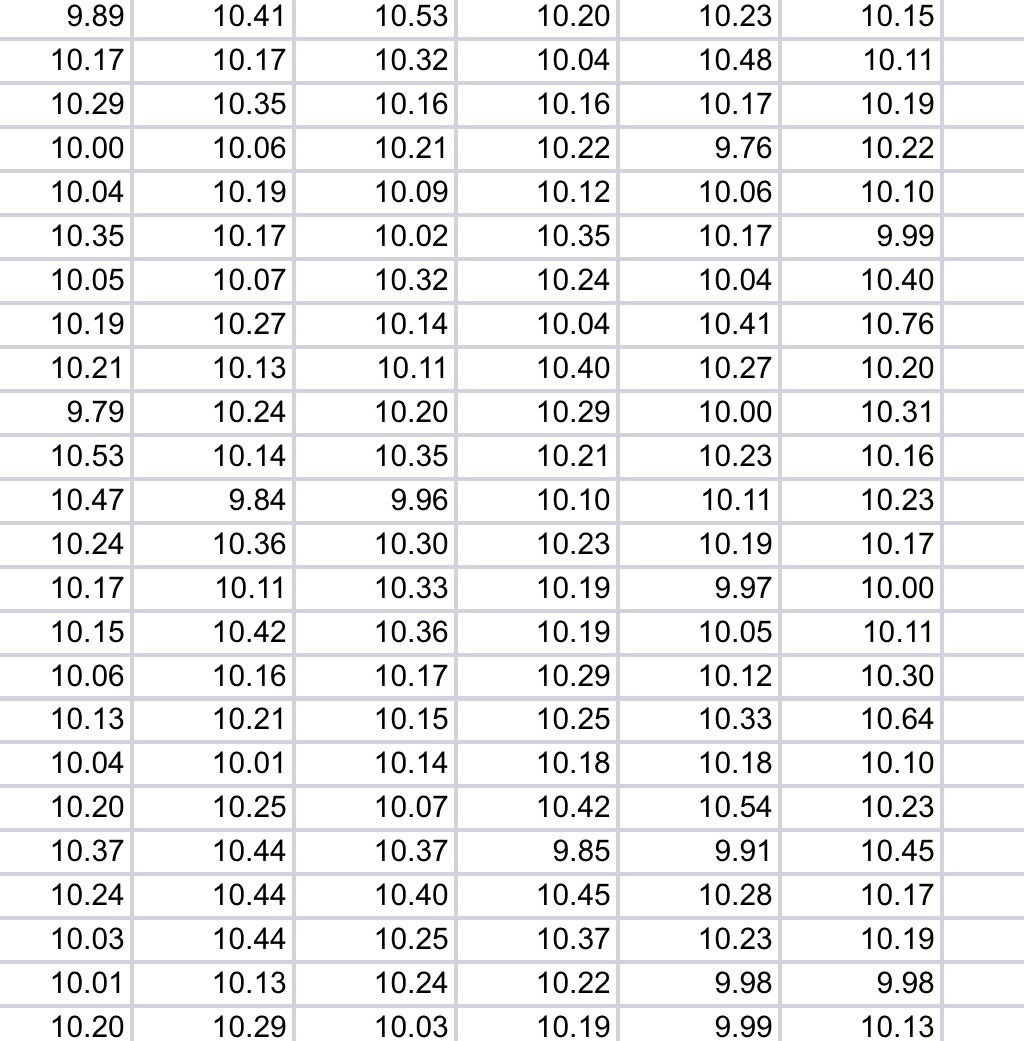

Step 1: What are we trying to decide? We certainly want to know what fill target should we recommend. The issues is that defects(bottles that are under 10oz will cost 20% of price). But on the other hand if we target a high fill target, it costs more in ingredients. So we need to understand the trade- offs. Step 2: How would you measure it? In this case we should be concern about profit. But it is not always the case because in operations, a lot of times we only worry about the cost. But since we are given the price etc, we can use profit as what we want to measure in order to decide what target level we recommend. Then one of the questions we need to address is the defective rate. In order to understand this, we need to know if we start the machine rolling, what will the volume of the bottles be like? That is why they sampled 144 bottles. As you can see the weight of the bottles, based on the sample, varies. For the sample, they targeted 10.2oz, the bottles were all over the map with 12 of the bottles under 10oz(defective). If you plot the 144 bottles, it kind of centered around 10.2oz(as expected or else something else is wrong with your machine). Well, it does look kind of like a normal distribution(I know you don't ever want me to speak those words in your face). If you think it is good enough to be considered normally distributed, then life is relatively easy for you. Because if you target 10.2oz, with a standard deviation of . 16oz(measured in the sample), you can theoretically find out what percentage of your bottles will likely be under 10oz. In this case, it is about 10.56%. But you don't have to assume that it is normally distributed. You can always use 12 out of 144 as your defective rate(8%) as observed in the sample run. Then you problem is then what about 10.3oz, 10.loz? For example, I know the shampoo folks in Downey for Unilever simply makes run for different fill target and then observe the defective rates. There are plus and minus for that. For Lorex, let say we can assume that they are normally distributed. If you are real picky, you can use Chi-Square Statistical Test to validate that. If you are strange enough to want to know how to do that, email me and I will give you my notes on Chi-Square, very simple but useful. By the way in Excel, there are all kinds of functions that can calculate the % for you. Check my spreadsheet for that. Or you can consult your statistics textbook(if you haven't burn it by now). Now that we know the weights of the bottles(just an estimate), we can move on and try to figure out the profit correspond to each potential fill target. Step 3: Data Collection We know most of the data (someone collected that for us). But we have to massage them. For example, how do we calculate revenue, costs, etc. Step 4: Analysis. Because we have most of the data we need, including pricing information, we can make our decision base on profit estimates. It is appropriate to set up a P&L statement(Profit & Loss) so we can examine profit at different fill level. We know as we increase our fill level, we will use more ingredients but also reduce defects. First we have to decide on a time period or quantity, and I would suggest one batch. Because the cost figures are by batch. Each batch will yield about 169,088 oz. We can then calculate how many cases we can fill with a specific fill level, then we can calculate the defective rate(discussed before), then we can calculate the revenue. Ingredient cost(and all other blending related costs) per batch is the same for all levels. But the filling costs(labor, materials, overhead) are dependent on the number of bottles/cases and should be adjusted according for each fill level. So is re-packaging cost for seconds. Step 5: Decision. With the cost information calculated, then we have the profit estimates for each fill targets and then we can make our decision based on that. What we have to be careful is that we are not looking at service levels here. We are assuming no goodwill cost and the only penalty for defects is the reduction in price. Also, we care assuming that we can sell everything we produce, including unlimited amount of defects.