Question

Task 03. Question is based on this article: Policymakers Must Use Fiscal Stimulus in a Recession The CBO and Blinder-Zandi analyses bear out Romer's belief

Task 03.

Question is based on this article:

Policymakers Must Use Fiscal Stimulus in a Recession

The CBO and Blinder-Zandi analyses bear out Romer's belief that ARRA moderated the Great Recession. Jason Furman, who served as CEA chair in the second Obama term, argues based on recent fiscal stimulus research that "the tide of expert opinion" among policy-oriented economists and international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development was already shifting prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The "new view" of fiscal policy reverses most of the "old view" that prevailed leading up to the Great Recession ? and still may prevail among some policymakers, notwithstanding the bipartisan and near-unanimous support for the CARES Act as a COVID-19 emergency measure.[14]

Several policy shifts distinguish this new perspective, which features the following four principles:

Fiscal policy shouldn't be subordinate to monetary policy. Furman argues that fiscal policy is an essential tool to support aggregate demand and should not be subordinate to monetary policy, as many considered it to be before the Great Recession. In response to COVID-19, the Fed has cut its target interest-rate range from one that was already substantially lower than before the Great Recession essentially to zero,[15] eliminating its room for conventional interest rate cuts to stimulate aggregate demand in a weakening economy. Notwithstanding the significant quantitative easing and financial-market stabilization measures the Fed is now taking, the CARES Act and other fiscal policy measures are critical for fighting a COVID-19 recession, and fiscal policy will be a necessary complement to monetary policy in any future recession.[16]

Fiscal policy stimulates demand in a recession. Furman argues that evidence from the Great Recession shows that discretionary fiscal policy can be highly effective at stimulating aggregate demand when the Fed does not counter it by tightening. By stimulating economic growth while interest rates are low, well-targeted, deficit-financed stimulus measures may even encourage new investment despite increasing the deficit. This suggests that CBO's high-end estimates of ARRA's effect on output and employment, described in the box above, are likely to be much closer to the likely stimulus effects of those measures in a recession than its low-end estimates.

Recovery from the Great Recession was slowed by a premature turn toward budget austerity beginning in 2010, when concerns about budget deficits and debt prevented policymakers from adopting further needed stimulus. Instead, the winding down of ARRA spending became a drag on growth in 2010-11, as Figure 1 shows. Congressional opposition to continuing fiscal stimulus in order to promote a stronger recovery was fueled by the emergence of small-government populist Tea Party sentiments and since-discredited academic evidence purporting to show that levels of debt beyond a 90-percent-of-GDP-threshold were damaging to growth[17] and that cutting government spending in a recession could increase growth[18] ? contrary to the overwhelming evidence that cutting spending or raising taxes in a recession is contractionary.

3. Fiscal space constrains stimulus less than previously thought. Furman rejects the idea that the United States now faces a debt crisis that requires immediate austerity, noting that "fiscal stimulus is less constrained by fiscal space than previously appreciated." Fiscal space is the amount of room a country has to increase deficits and debt without debt holders losing confidence and provoking a debt crisis with spiking interest rates, falling government bond prices, and the risk of a sharp contraction in economic activity. Furman does not call for abandoning fiscal responsibility, but even before COVID-19 created the need for an urgent and robust response, he rejected the idea that we - have, or are near to having, a debt crisis that precludes borrowing for stimulus in a recession.

Both former CBO Director Douglas Elmendorf and current CBO Director Phillip Swagel agree with that position, with Swagel stating last summer, "when there's a financial crisis and a recession . . . countries that respond with expansionary policy do better. And it looks like the United States has the fiscal space to do that. . . . Interest rates are low. The federal government is able to borrow. So [the debt situation] is not an immediate crisis. . . . It's a long-term challenge."[19]

Similarly, Elmendorf wrote in the Washington Post last year, "Yes, we have a serious long-term debt problem, but no, that problem does not make anti-recessionary budget policy impossible or unwise."[20] The fact that interest rates were at a historically low level and expected to remain so for many years even at the time he was writing last summer led Elmendorf to the following conclusion, which is even more true now:

Federal borrowing is thus less costly and creates less risk for the federal government than many of us predicted several years ago ? and, according to economic analyses, does less harm to the economy even in the long run. In addition, the funds used as stimulus do not disappear: They support government spending for public goods and services, or they lower taxes so that households have more resources for their private activities.

In sum, we have plenty of capacity in the federal budget to undertake vigorous countercyclical tax and spending policies when the next recession arrives. Given the economic and social costs of recessions, we should undertake such policies (emphasis added).

4. Sustained fiscal expansion could be necessary. The low-interest-rate environment and the experience with sluggish recoveries from the Great Recession and the milder recessions in 1990-1991 and 2001 lead to the fourth principle in the new view of fiscal policy: it may be desirable to pursue sustained fiscal expansion.

Before the Great Recession, economists who were sympathetic to fiscal stimulus in principle were hesitant to recommend it in practice due to concerns that delays in recognizing the need and enacting the necessary legislation would delay the stimulus from taking effect until monetary stimulus had already kicked in and the economy was recovering at a reasonable pace. That could potentially be destabilizing and lead the Fed to raise interest rates to prevent overheating, largely offsetting the stimulus. The net result would simply be an unnecessary increase in debt to finance stimulus that was no longer needed and the Fed had largely offset.

In today's low-interest-rate global economy, however, the case for more sustained stimulus in the face of deficient aggregate demand is much stronger, especially if the stimulus takes the form of productive investment.[21] The Great Recession wreaked long-lasting damage on the economy's productive capacity, as a result of the sharp contraction in productive investment and the effects of long-term unemployment on workers' skills, employment prospects, labor force participation, and earnings, as described earlier. Stronger and more sustained fiscal stimulus could have attenuated these effects substantially. Avoiding additional damage due to COVID-19 is now essential.[22]

Q: The article points to empirical evidence indicating that in recessions discretionary fiscal policy can be effective at stimulating aggregate demand if the interest rate is low and the central bank does not counter the fiscal expansion by monetary tightening. Why is fiscal policy more effective in such a situation compared to other conditions? Please use the IS-LM framework to explain your answer.

B...

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

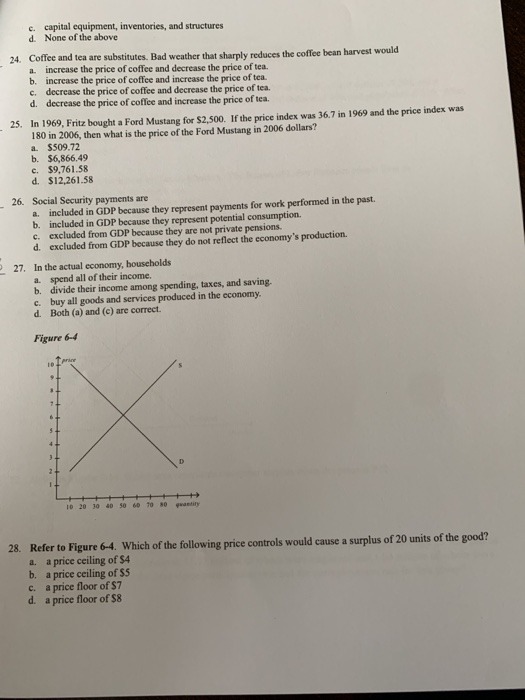

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started