Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

That is the second time I ask, I didnt get the right answer for all Questions, I hope that you will answer all of questions

That is the second time I ask, I didnt get the right answer for all Questions, I hope that you will answer all of questions with a good answer. I hope the answer will be covered for the points that apply to each question.

organizational theory

The Gillette case (Gillette Metal Fabrication)

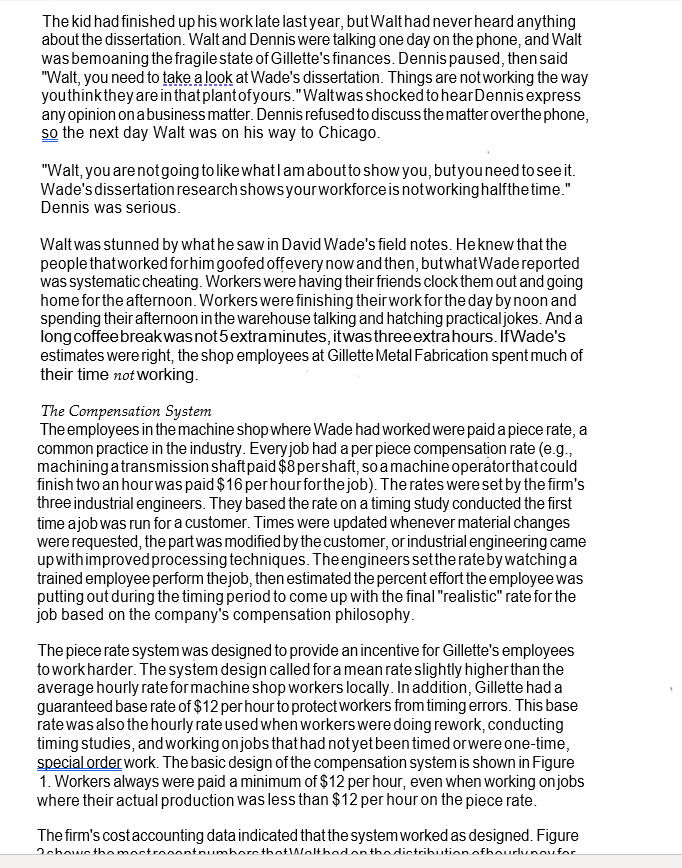

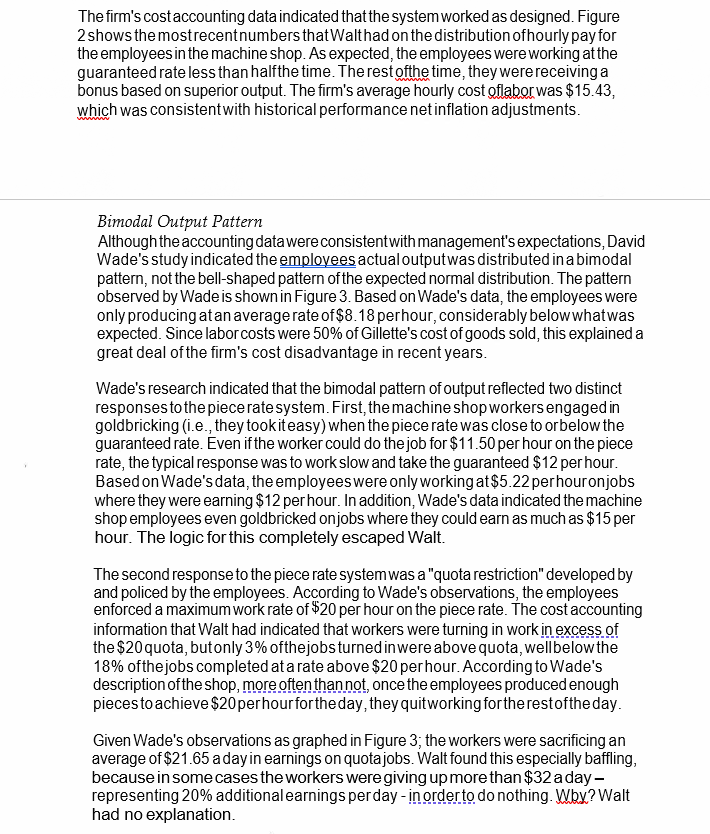

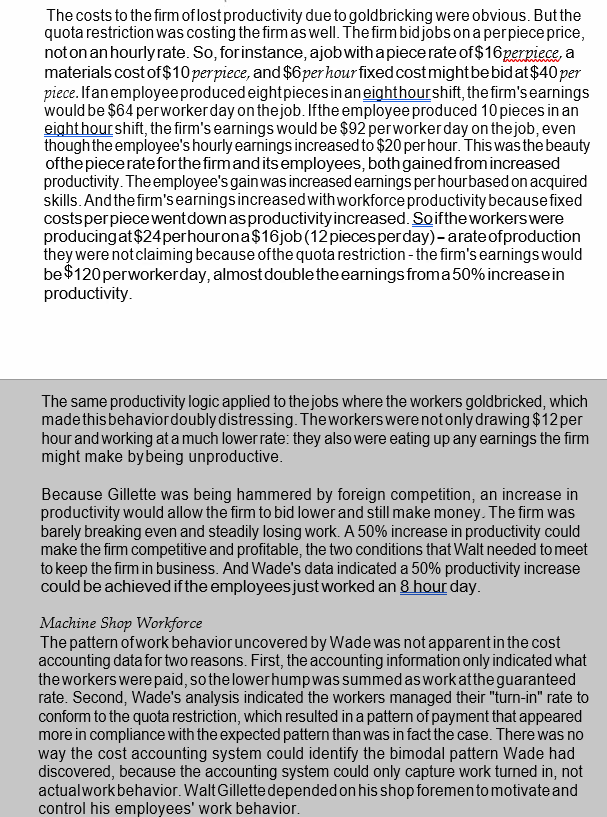

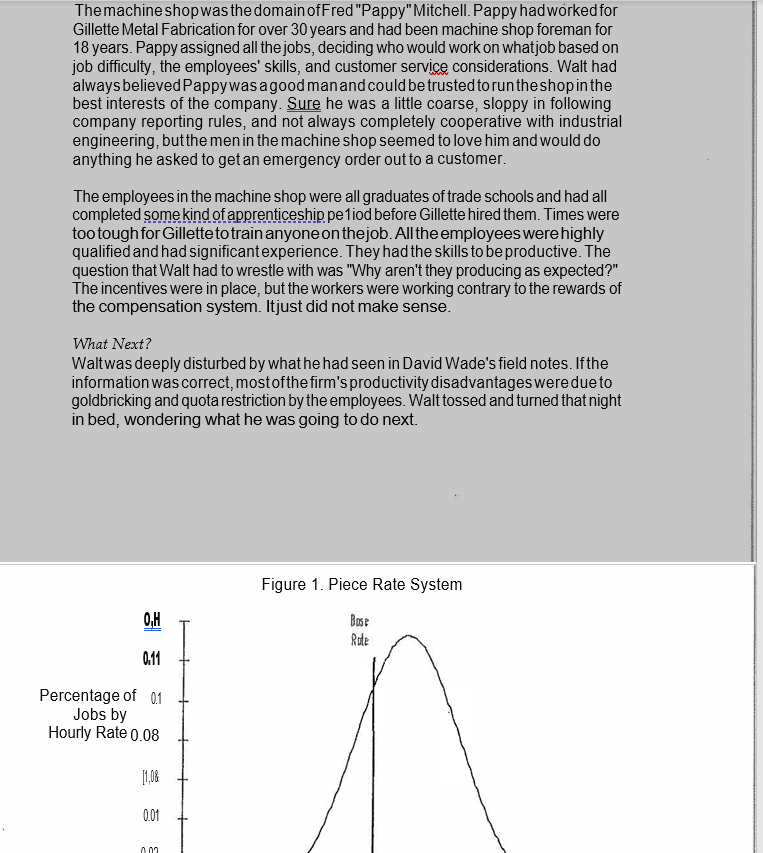

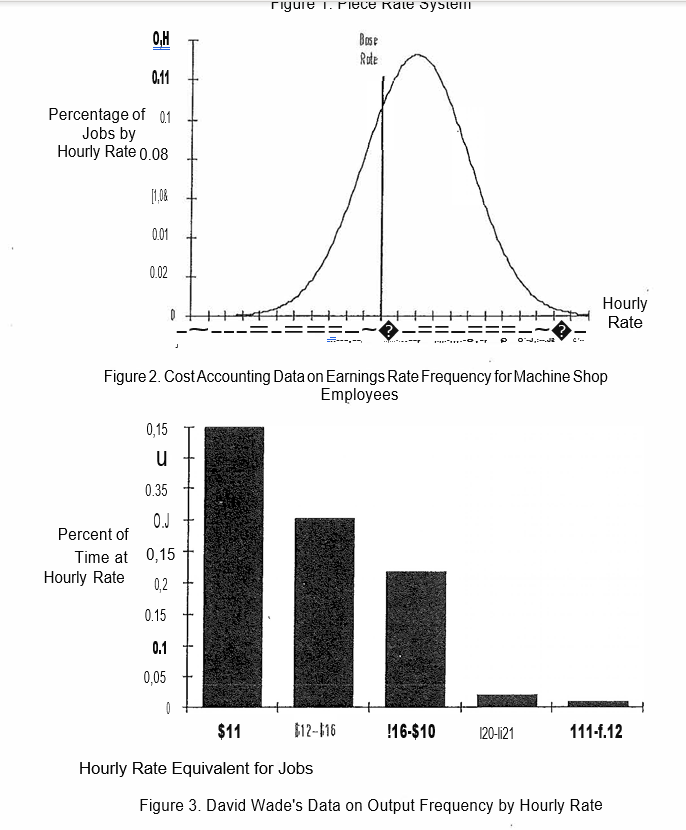

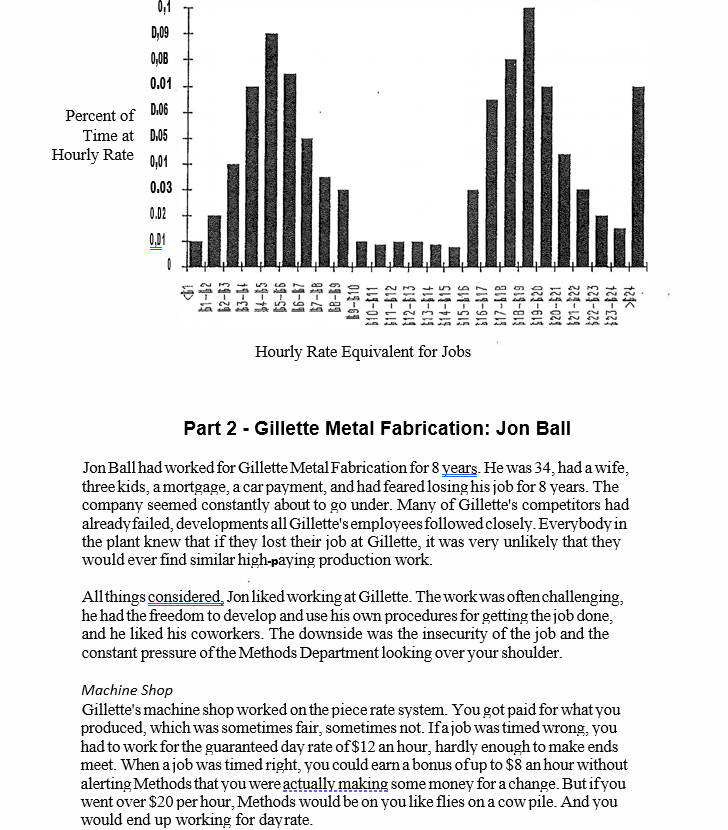

Gillette Metal Fabrication: Walt Gillette. Walt Gillette took over Gillette Metal Fabrication from his father, William, in 1984. The company was founded in 1947 as a subcontractor doing work for parts fmns supplying the automobile industry. Durable goods sales boomed in the post-WWII period as consumers made up for the shortages of the war years, and Gillette Metal Fabrication grew significantly during this period. The company continued to prosper over the next two decades as automobile sales soared in direct proportion to the wealth of the American consumer. The company never grew beyond approximately 200 employees, but the margins in the business were good. As a result, the Gillettes amassed enough of a fortune to be comfortable, but not ostentatious. The company began to encounter difficulties with the first oil shock. As the automobile industry's fortunes waned under the combined effects of model downsizing and foreign automobile imports, Gillette Metal Fabrication fell on hard times. The company managed to survive largely because William Gillette was willing to operate the company without drawing a salary, something Walt had done as well. The Gillette's long established relationships in the industry had generated enough work to keep the company alive, althoughiust barely. By 1989, Walt had 5 hard years behind him and was beginning to wonderifthere was any point in keeping the company going. Japanese suppliers and subcontractors had become a significant presence in the industry, and it did not look like Gillette could compete with them. For reasons that were not apparent to Walt, Gillette's Japanese competitors were selling at prices well below Gillette's production costs. Walt did not see how they could make any money at the prices they were charging. They had the same basic labor costs that Gillette had the same materials costs, and they bought their equipment from the same manufacturers. But they were beating Gillette's prices by a significant amount on every contract that came up for bid. Walt figured he could keep the company open for another year the way things were going. But ifprofits did not improve, he was going to close down. There were no other options. "The Project" Walt had gone to high school and college with Dennis Gordon. Dennis had continued his education right through to a Ph.D. in anthropology. He now worked as a professor at Midwestern University in Chicago. He and Walt were lifelong friends, so no favor seemed too big. When Dennis asked ifhe could send one ofhis Ph.D. students - a young man named David Wade - down to do a year long field study inside Gillette's machine shop, Walt was not thrilled. But it was Dennis. After meeting the kid and finding out that he had prior experience as a machine operator, Walt okayed the project, figuring at worse he was getting a motivated employee for a year and was helping the university The kid had finished up his work late lastyear, but Walthad never heard anything about the dissertation. Walt and Dennis were talking one day on the phone, and Walt was bemoaning the fragile state of Gillette's finances. Dennis paused, then said "Walt, you need to take a look at Wade's dissertation. Things are not working the way youthink they are in that plantofyours."Waltwas shocked to hear Dennis express any opinion on a business matter. Dennis refused to discuss the matter over the phone, so the next day Walt was on his way to Chicago. "Walt, you are not going to like whatlam about to show you, butyou need to see it. Wade's dissertation research shows yourworkforce is notworking halfthe time." Dennis was serious. Waltwas stunned by what he saw in David Wade's field notes. He knew that the people that worked for him goofed offevery now and then, butwhatWadereported was systematic cheating. Workers were having their friends clock them out and going home for the afternoon. Workers were finishing their work for the day by noon and spending their afternoon in the warehouse talking and hatching practical jokes. Anda long coffeebreakwasnot5extraminutes, it was three extrahours. IfWade's estimates were right, the shop employees at Gillette Metal Fabrication spent much of their time not working. The Compensation System The employees in the machine shop where Wade had worked were paid a piece rate, a common practice in the industry. Everyjob had a per piece compensation rate (e.g., machining atransmission shaft paid $8 pershaft, so a machine operator that could finish two an hourwas paid $16 per hour for the job). The rates were set by the firm's three industrial engineers. They based the rate on a timing study conducted the first time ajob was run for a customer. Times were updated whenever material changes were requested, the part was modified by the customer, or industrial engineering came up with improvedprocessing techniques. The engineers setthe rate by watching a trained employee perform thejob, then estimated the percent effort the employee was putting out during the timing period to come up with the final "realistic" rate for the job based on the company's compensation philosophy. The piece rate system was designed to provide an incentive for Gillette's employees to work harder. The system design called for a mean rate slightly higher than the average hourly rate formachine shop workers locally. In addition, Gillette had a guaranteed base rate of $12 per hour to protect workers from timing errors. This base rate was also the hourly rate used when workers were doing rework, conducting timing studies, and working onjobs that had notyet been timed orwere one-time, special order work. The basic design of the compensation system is shown in Figure 1. Workers always were paid a minimum of $12 per hour, even when working onjobs where their actual production was less than $12 per hour on the piece rate. The firm's cost accounting data indicated that the system worked as designed. Figure 2 chowe thomactrocontoumbore thotWolthodon the distribution ofhourlnoufor The firm's cost accounting data indicated that the system worked as designed. Figure 2 shows the mostrecentnumbers thatWalthad on the distribution ofhourly pay for the employees in the machine shop. As expected, the employees were working at the guaranteed rate less than halfthe time. The rest ofthe time, they were receiving a bonus based on superior output. The firm's average hourly cost oflabor was $15.43, which was consistent with historical performance net inflation adjustments. Bimodal Output Pattern Although the accounting data were consistentwith management's expectations, David Wade's study indicated the employees actual output was distributed in a bimodal pattern, not the bell-shaped pattern of the expected normal distribution. The pattern observed by Wade is shown in Figure 3. Based on Wade's data, the employees were only producing at an average rate of $8.18 perhour, considerably below whatwas expected. Since labor costs were 50% of Gillette's cost of goods sold, this explained a great deal of the firm's cost disadvantage in recent years. Wade's research indicated that the bimodal pattern of output reflected two distinct responses to the piecerate system. First, the machine shop workers engaged in goldbricking (i.e., they took it easy) when the piece rate was close to orbelow the guaranteed rate. Even if the worker could do the job for $11.50 per hour on the piece rate, the typical response was to work slow and take the guaranteed $12 per hour. Based on Wade's data, the employees were only working at $5.22 per houronjobs where they were earning $12 per hour. In addition, Wade's data indicated the machine shop employees even goldbricked onjobs where they could earn as much as $15 per hour. The logic for this completely escaped Walt. The second response to the piece rate system was a "quota restriction" developed by and policed by the employees. According to Wade's observations, the employees enforced a maximum work rate of $20 per hour on the piece rate. The cost accounting information that Walt had indicated that workers were turning in work in excess of the $20 quota, butonly 3% ofthejobs turned inwere above quota, wellbelow the 18% ofthejobs completed at a rate above $20 per hour. According to Wade's description of the shop, more often than not, once the employees produced enough pieces to achieve $20 per hour forthe day, they quitworking forthe restoftheday. Given Wade's observations as graphed in Figure 3, the workers were sacrificing an average of $21.65 a day in earnings on quota jobs. Walt found this especially baffling, because in some cases the workers were giving up more than $32 a day- representing 20% additional earnings per day - in order to do nothing. Why? Walt had no explanation. The costs to the firm of lostproductivity due to goldbricking were obvious. But the quota restriction was costing the firm as well. The firm bidjobs on a perpiece price, not on an hourly rate. So, forinstance, ajob with a piece rate of$ 16 perpiece, a materials costof$10 perpiece, and $6per hour fixed cost might bebidat $40 per piece.Ifan employeeproduced eightpiecesin an eighthour shift, the firm's earnings would be $64 perworker day on thejob. Ifthe employee produced 10 pieces in an eight hour shift, the firm's earnings would be $92 perworkerday on the job, even though the employee's hourly earnings increased to $20 per hour. This was the beauty ofthe piecerate forthe firm and its employees, both gained from increased productivity. The employee's gain was increased earnings per hour based on acquired skills. And the firm's earnings increased with workforce productivity because fixed costs per piece went down as productivity increased. Soifthe workers were producing at $24 per hourona $16job (12 pieces per day) - arate ofproduction they were not claiming because ofthe quota restriction - the firm's earnings would be $120 perworkerday, almost double the earnings from a 50% increase in productivity The same productivity logic applied to the jobs where the workers goldbricked, which made this behavior doubly distressing. The workers were not only drawing $12 per hour and working at a much lower rate: they also were eating up any earnings the firm might make by being unproductive. Because Gillette was being hammered by foreign competition, an increase in productivity would allow the firm to bid lower and still make money. The firm was barely breaking even and steadily losing work. A 50% increase in productivity could make the firm competitive and profitable, the two conditions that Walt needed to meet to keep the firm in business. And Wade's data indicated a 50% productivity increase could be achieved if the employees just worked an 8 hour day. Machine Shop Workforce The pattern ofwork behavior uncovered by Wade was not apparent in the cost accounting data for two reasons. First, the accounting information only indicated what the workers were paid, so the lower hump was summed as work atthe guaranteed rate. Second, Wade's analysis indicated the workers managed their "turn-in" rate to conform to the quota restriction, which resulted in a pattern of payment that appeared more in compliance with the expected pattern than was in fact the case. There was no way the cost accounting system could identify the bimodal pattern Wade had discovered, because the accounting system could only capture work turned in, not actualworkbehavior. Walt Gillette depended on his shop foremento motivate and control his employees' work behavior. The machine shop was the domain ofFred "Pappy"Mitchell. Pappy hadworked for Gillette Metal Fabrication for over 30 years and had been machine shop foreman for 18 years. Pappy assigned all the jobs, deciding who would work on whatjob based on job difficulty, the employees' skills, and customer service considerations. Walt had always believed Pappy was a good manand could be trusted to run the shopinthe best interests of the company. Sure he was a little coarse, sloppy in following company reporting rules, and not always completely cooperative with industrial engineering, but the men in the machine shop seemed to love him and would do anything he asked to get an emergency order out to a customer. The employees in the machine shop were all graduates of trade schools and had all completed some kind of apprenticeship peliod before Gillette hired them. Times were tootough for Gillette to train anyone on thejob. All the employees were highly qualified and had significant experience. They had the skills to be productive. The question that Walt had to wrestle with was "Why aren't they producing as expected?" The incentives were in place, but the workers were working contrary to the rewards of the compensation system. Itjust did not make sense. What Next? Waltwas deeply disturbed by what he had seen in David Wade's field notes. Ifthe information was correct, mostofthe firm's productivity disadvantages were due to goldbricking and quota restriction by the employees. Walt tossed and turned that night in bed, wondering what he was going to do next. Figure 1. Piece Rate System 0, Bose Rode 0.11 Percentage of 0.1 Jobs by Hourly Rate 0.08 0.01 rigure 1. Piece Rale System 0,4 Bose Rote 0.11 Percentage of 0.1 Jobs by Hourly Rate 0.08 n. 0.01 0.02 HAH +++ Hourly Rate 0JJZ Figure 2. Cost Accounting Data on Earnings Rate Frequency for Machine Shop Employees 0,15 u 0.35 0.J Percent of Time at 0,15 Hourly Rate 0,2 0.15 0.1 0,05 0 $11 012-116 !16-$10 120-li21 111-4.12 Hourly Rate Equivalent for Jobs Figure 3. David Wade's Data on Output Frequency by Hourly Rate D.09 0,0 0.01 Percent of D.06 Time at D.05 Hourly Rate 0,01 0.03 0.02 0,01 5Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started