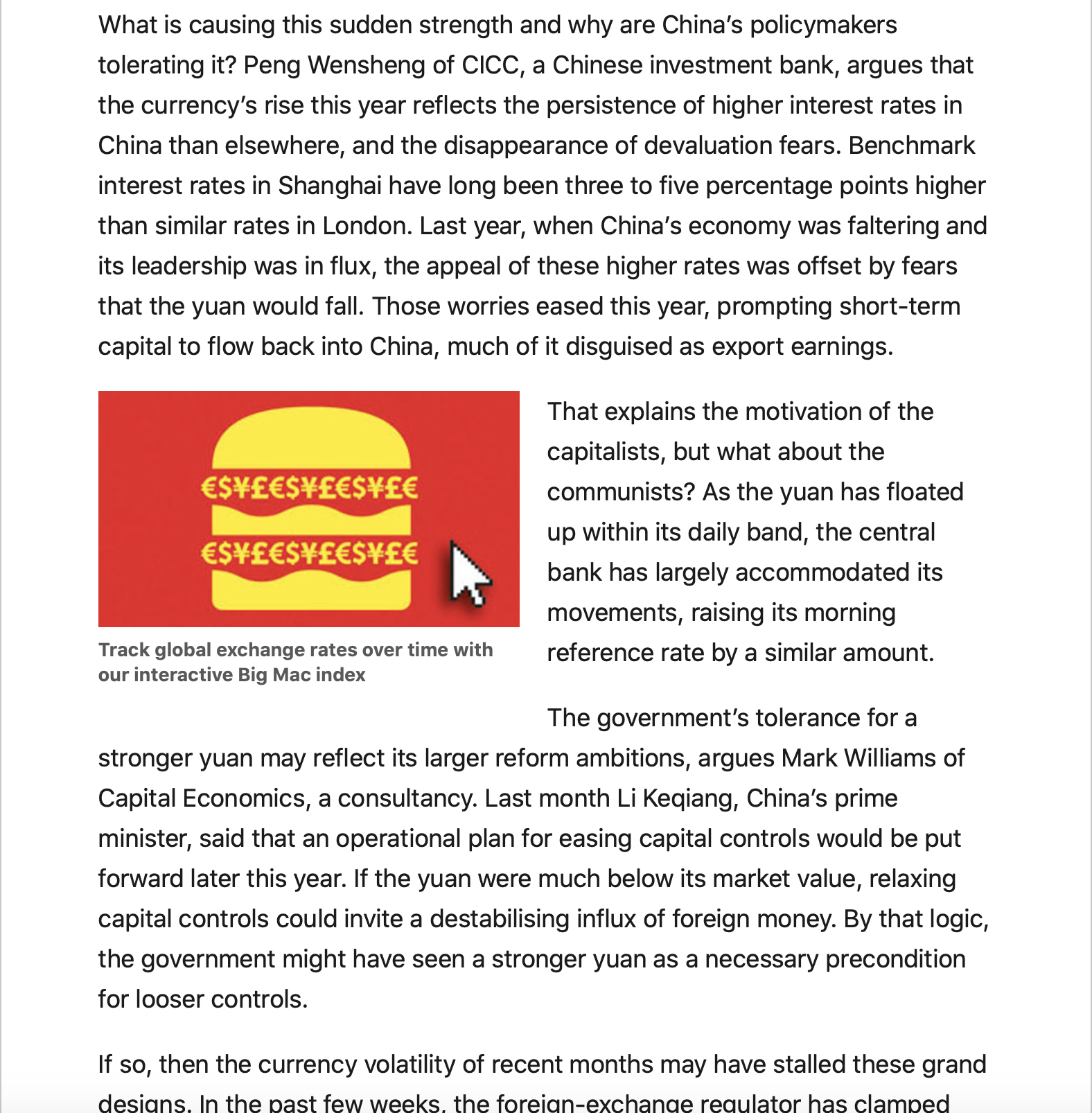

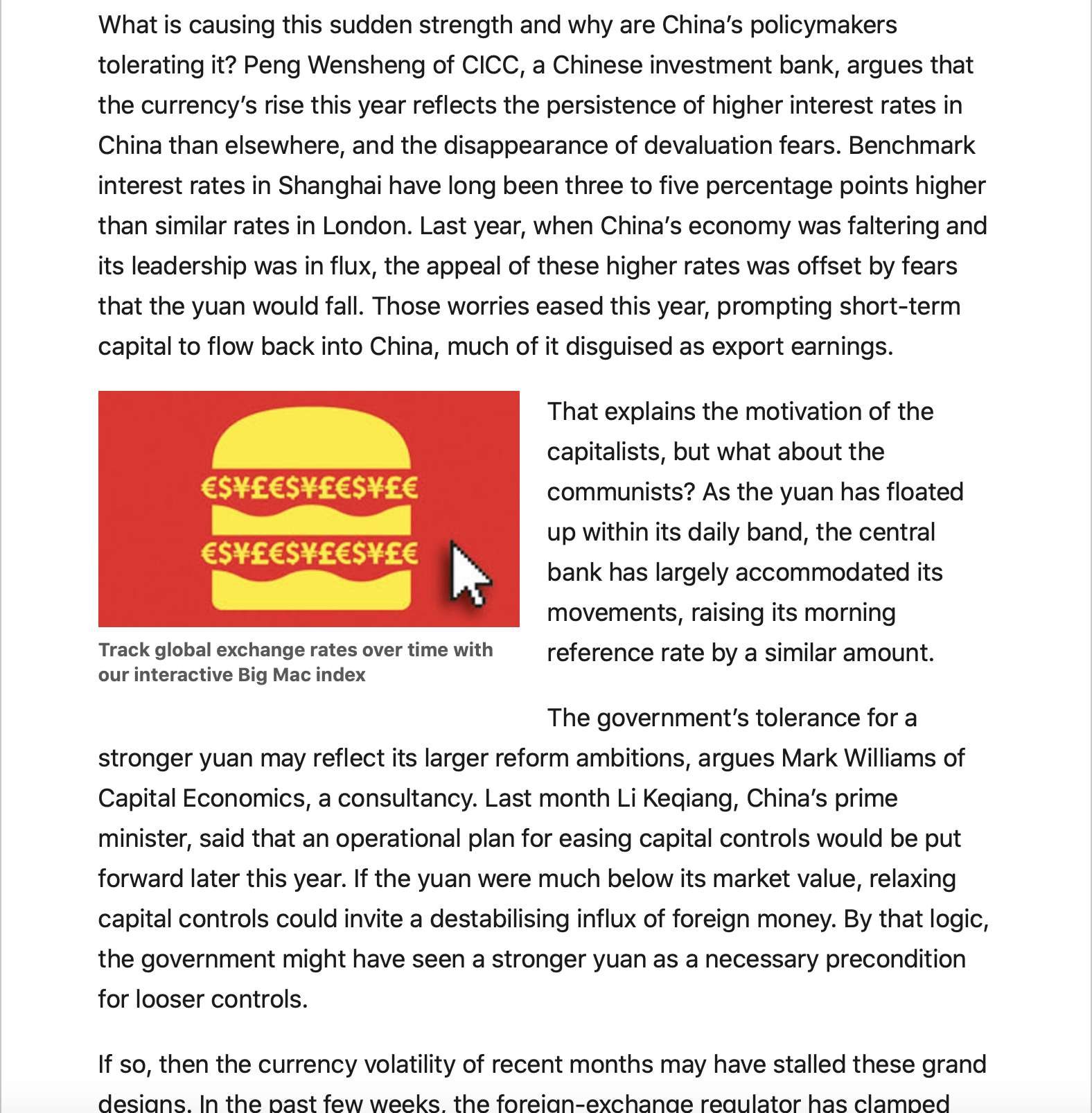

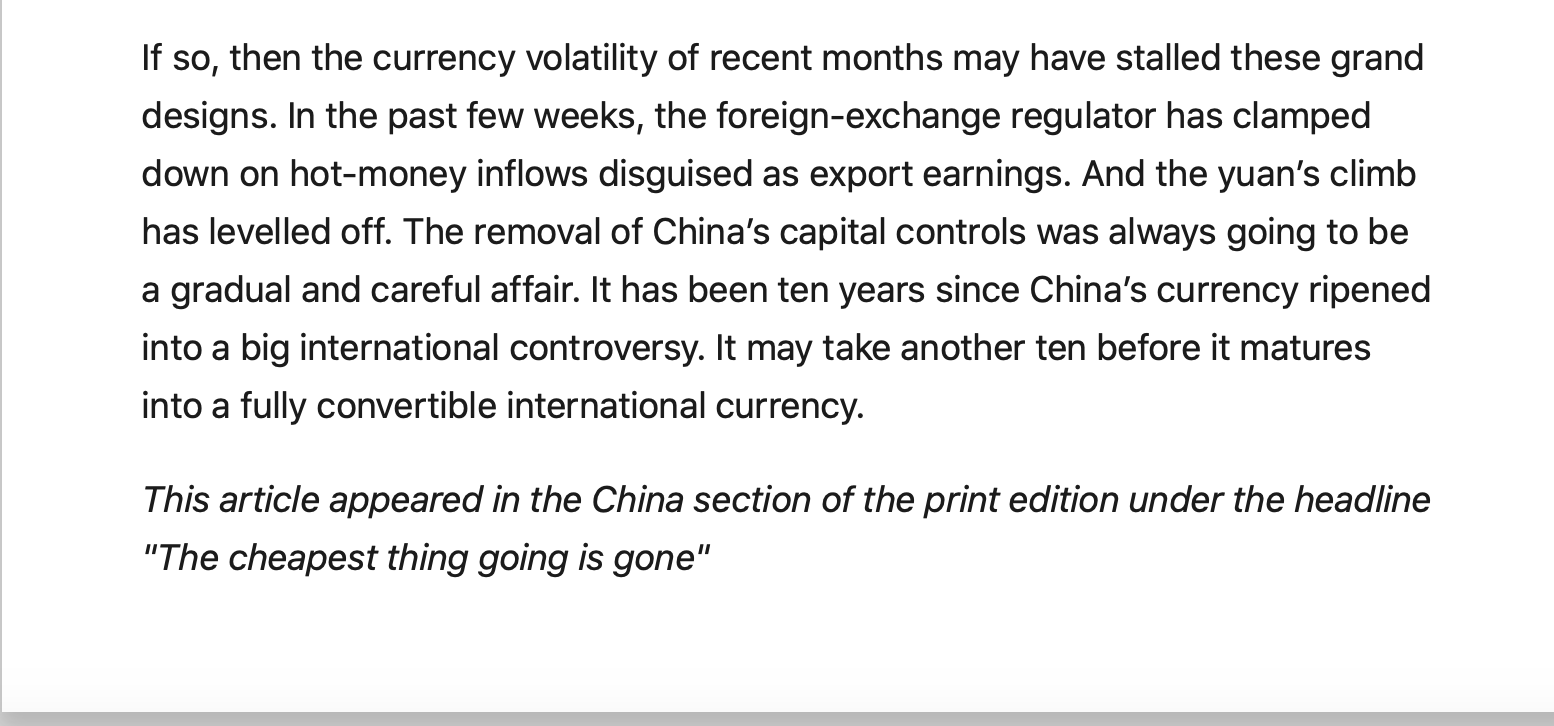

The cheapest thing going is gone After enduring a decade of criticism for its weakness, China's currency now looks uncomfortably strong Jun 15th 2013 After enduring a decade of criticism for its weakness, China's currency now looks uncomfortably strong TEN years ago, the yuan made its debut as a global economic bugbear. In June 2003, America's then treasury secretary, John Snow, publicly encouraged China to loosen a policy under which its currency was pegged at 8.28 to the dollar. The next month four senators wrote an angry letter urging Mr Snow to investigate China for "currency manipulation". The country was intentionally undervaluing its currency, argued Charles Schumer, a Democratic senator for New York. "The result is that everything they sell to other countries is the cheapest thing going." A decade later, Mr Schumer and other senators are still bashing the yuan: eight of them reintroduced a bill last week that would slap duties on currency manipulators. But much else has changed. Now allowed to float by 1% a day on either side of a reference rate set each morning by the central ban k, the yuan closed trading on May 27th at 6.12 to the dollar, 35% stronger than its June 2003 rate. It has risen more against the dollar since March than it rose in the whole of last year, and its climb against Japan's currency has been even steeper. Since November, when the markets began to anticipate dramatic monetary easing in Japan, the yuan has gained over 20% against a weakened ven. I Redback rising China's competitiveness on world \"WWW"? \"\"53\"\" 2003-100 markets depends not only on the price 150 of its currency but also on the price of the Economist' yuan index its goods and workers at home. The Bank for International Settlements calculates a \"real" exchange rate for 61 economies that takes account of inflation differences between them. Since 2010 China's real exchange rate, 2003 05 06 0? 03 09 1 11 1213_ weighted by trade, has risen faster than Sources: the Economist: \"trade-weighted and adjusted \"WWW" \"'\"dm'm'cm any other, with the sole exception of Venezuela's. The price of labour is also rising faster in China than in its principal trading partners. The Economist has calculated an alternative "real" exchange rate, weighted by trade with America, the euro area and Japan, which takes account of unit labour costs in all four economies. By this measure, China's real exchange rate has strengthened by almost 50% since Messrs Snow and Schumer began their currency-bashing ten years ago. If the yuan was the cheapest thing going back then, now its cheapness has all but gone. Some economists, such as Diana Choyleva of Lombard Street Research, even wonder if the yuan is now overvalued. This longterm strengthening of China's real exchange rate reflects deep historical forces, such as China's rapid economic growth, stronger labour laws, and shrinking workingage population. But the more recent surge in its nominal exchange rate is puzzling and awkward. It comes at a time of disappointing orowth. fallino inflation (onlv 2.1% in the vear to Mavl and flaooino exports What is causing this sudden strength and why are China's policymakers tolerating it? Peng Wensheng of CICC, a Chinese investment bank, argues that the currency's rise this year reflects the persistence of higher interest rates in China than elsewhere, and the disappearance of devaluation fears. Benchmark interest rates in Shanghai have long been three to five percentage points higher than similar rates in London. Last year, when China's economy was faltering and its leadership was in flux, the appeal of these higher rates was offset by fears that the yuan would fall. Those worries eased this year, prompting shortterm capital to flow back into China, much of it disguised as export earnings. That explains the motivation of the capitalists, but what about the $$$ communists? As the yuan has floated up within its daily band, the central bank has largely accommodated its movements, raising its morning Track global exchange rates over time with reference rate by a similar amount. our interactive Big Mac index $SS k The government's tolerance for a stronger yuan may reflect its larger reform ambitions, argues Mark Williams of Capital Economics, a consultancy. Last month Li Keqiang, China's prime minister, said that an operational plan for easing capital controls would be put forward later this year. If the yuan were much below its market value, relaxing capital controls could invite a destabilising influx of foreign money. By that logic, the government might have seen a stronger yuan as a necessary precondition for looser controls. If so, then the currency volatility of recent months may have stalled these grand desions. In the past few weeks. the foreignexchange regulator has clamped If so, then the currency volatility of recent months may have stalled these grand designs. In the past few weeks, the foreignexchange regulator has clamped down on hotmoney inflows disguised as export earnings. And the yuan's climb has levelled off. The removal of China's capital controls was always going to be a gradual and careful affair. It has been ten years since China's currency ripened into a big international controversy. It may take another ten before it matures into a fully convertible international currency. This article appeared in the China section of the print edition under the headline "The cheapest thing going is gone"