Question

The consultant has included some cost items that either do not increase with the purchase of the Orion machine (e.g., some taxes and insurance premiums)

The consultant has included some cost items that either do not increase with the purchase of the Orion machine (e.g., some taxes and insurance premiums) or were never spent at all (e.g., inflated overhead rate). What principles and concepts would you consider for including such cost items in the cost-plus bids?

F) The consultant has included some cost items that either do not increase with the purchase of the Orion machine (e.g., some taxes and insurance premiums) or were never spent at all (e.g., inflated overhead rate). What principles and concepts would you consider for including such cost items in the cost-plus bids?

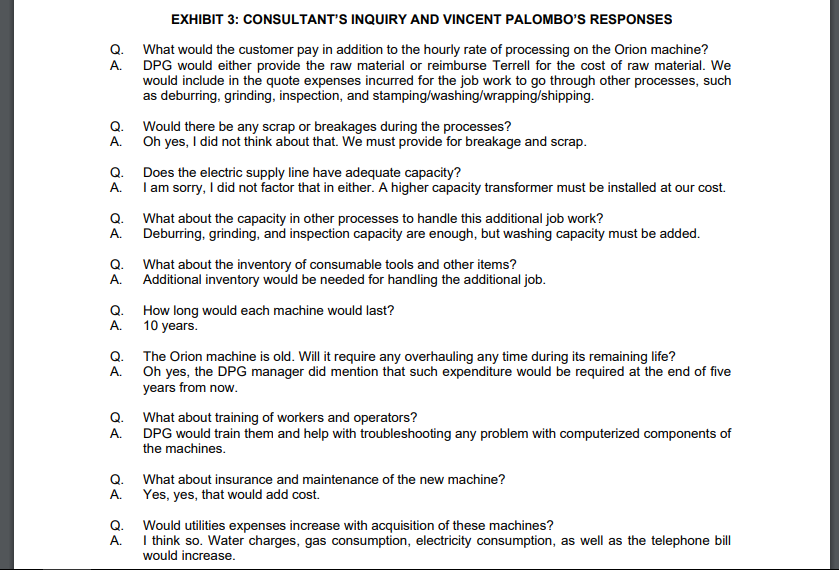

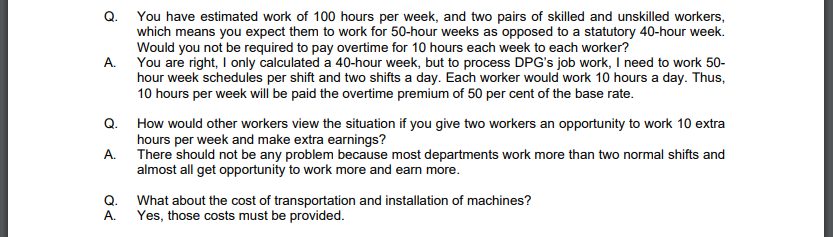

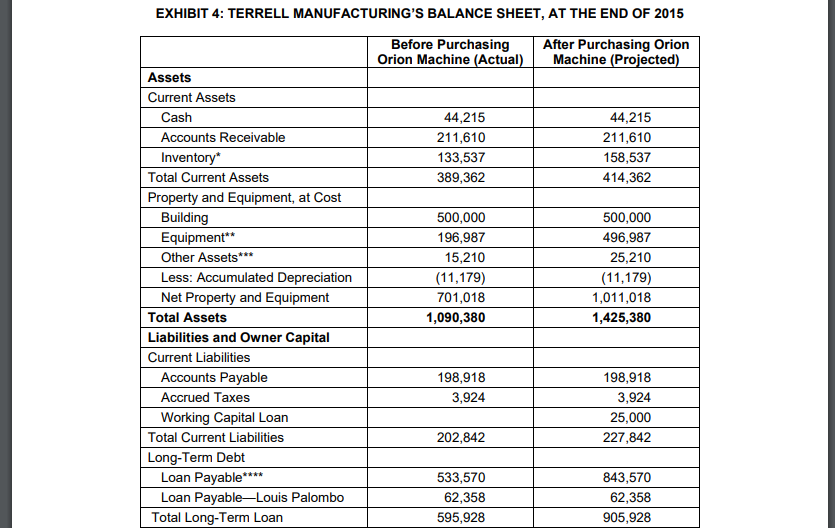

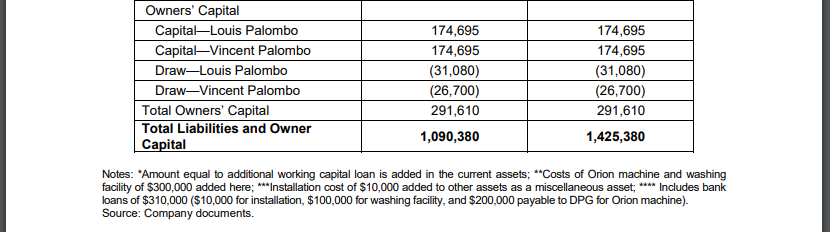

vey Publishing W18526 TERRELL MANUFACTURING: BUYING A MACHINE Bhavesh Patel and Vincent Palombo wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G ON1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com. Copyright 2018, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2018-08-31 Terrell Manufacturing (Terrell) was a family-owned small business in Cleveland, Ohio. It supplied hydraulic manifoldspipe fittings with several lateral outlets to connect to other pipesfor the steel, plastics, and valve industry. Manifolds simplified the numerous connections, formerly provided by a series of hoses and tubes, resulting in an accurate and simple design. Demag Plastic Group (DPG), a large firm with global operations, had one facility near Terrell. DPG produced manifolds for its own use and also purchased manifolds from Terrell for additional requirements. DPG was Terrell's most important customer, providing more than 30 per cent of Terrell's revenue. Toward the end of 2015, DPG decided to stop producing manifolds and approached Terrell with a proposal: Terrell could buy DPG's Giddings & Lewis (G&L) Orion Machining Center (the Orion machine) and use it to process what would be additional orders from DPG. DPG would pay a 10 per cent markup on Terrell's approved cost to process DPG's orders. TERRELL MANUFACTURING Terrell Manufacturing was established by George Terrell in 1954. In its early years, the company provided manifolds primarily for the steel industry. The steel industry was growing at that time, resulting in strong growth for Terrell. Terrell added the plastics industry to its portfolio in the early 1960s, when Van Dorn Corporation (Van Dorn), a Cleveland-based producer of plastic moulding machines, began to use hydraulic manifolds as a replacement for its current system of hoses and tubes. Van Dorn gave the order for its manifold requirements to Terrell, creating Terrell's first market diversification. As a result of its efficient work, Terrell soon became well-known in the plastics industry for its ability to produce complex, high-quality manifolds. As the plastics industry flourished in the 1970s, Terrell grew again. By then, Terrell had large machines capable of machining manifolds of up to 10,000 pounds (4.5 metric tons). In early 1994, Van Dorn purchased an Orion machine and began producing manifolds in its own facility. The Orion machine was a technological feat in its ability to produce manifolds at speeds three to four times faster than conventional equipment. As a result, Terrell lost more than a quarter of its business. When George Terrell died in 1996, he left his business to his three daughters, none of whom was active in the company. Louis Palombo was acting as president of Terrell at that time. For nearly a decade, Terrell remained stagnant without any major decision or initiativeno new investment, no marketing, and no strategic plan. Key personnel began to leave, and overall sales declined from a high of US$3.5 million' in 1994 to $2.1 million in 2004. In December 2004, Palombo bought Terrell. By then, Vincent, Palombo's son, was also working for Terrell. For the year ending December 2004, Terrell achieved profits of $44,000 based on sales of $2.1 million. The company had 17 employeesthree in management positions and 14 in production activity. As the new owner, Palombo purchased a DeVlieg boring mill, fully retrofitted it at some cost, and placed it into production in March 2005. The DeVlieg boring mill became the most accurate and modern machining equipment in Terrell's facility (see Exhibits 1 and 2). THE OPPORTUNITY Van Dorn became Demag Plastic Group (DPG) after it was bought by a German firm in 2002. The new management continuously reviewed the company's operations and strategies to improve profitability and focus on the main business. At one stage, management decided to shut down the company's manifold operation and outsource the manifolds from a reliable supplier. They naturally thought of Terrell, which was already supplying DPG and was nearby. DPG approached Palombo and Vincent in December 2015, inviting them to bid on DPG's line of hydraulic manifolds, with an annual use that translated to sales of approximately $500,000 Terrell did not have enough capacity to meet DPG's total requirements without reducing Terrell's other customer base. When this limitation was expressed, DPG made an additional offer: DPG would sell its 20-year-old Orion machine to Terrell at an upfront cost of $200,000. DPG was open to negotiating the terms of payment, if doing so would help Terrell. The Orion machine would replace Terrell's initial two processes (see Exhibits 1 and 2), and Terrell would use its existing machines for the remaining processes needed to complete the manifolds made on the Orion machine for DPG. DPG asked Terrell to establish the base hourly rate for processing DPG's orders on the Orion machine and on Terrell's existing equipment. DPG would then discuss and negotiate the markup to determine the hourly rate that it would pay to Terrell. The offer came with one condition: Terrell could not use the spare capacity of the Orion machine to process orders for DPG's competitors. DPG was also concerned about Terrell's capabilities because of the significant technological skills required to operate the Orion machine. DPG, therefore, offered to train Terrell's selected operators and help with troubleshooting should the need arise, all free of cost. If everything went well for both companies, DPG would be willing to offer its second Orion machine to Terrell at some later date. Vincent thought this offer represented a great opportunity. The technological advancement, backed by an experienced multinational customer such as DPG, could give Terrell an additional advantage over its competitors. Vincent began calculating the hourly cost of processing on the Orion machine, so he would have a base for negotiating the rate. VINCENT'S ASSUMPTIONS After investigating the costs and issues, and discussing them with his father, Vincent concluded that the Orion machine could be used for 100 hours per week and 50 weeks per year. This usage implied two shifts of operations every day for five days a week and 50 weeks a year. One skilled worker and one semi-skilled worker would be required on each shift to operate the machine. A skilled worker would be paid $20 per hour and an semi-skilled worker, $15 per hour. Employee benefits could be calculated as an additional 30 per cent on employees' hourly wages. Vincent's accountant told him that the depreciable value of Terrell's building was $500,000. The Orion machine had a remaining life of 10 years. These assets could be depreciated on a straight-line basis at a rate of 10 per cent. Additional tooling expenses were expected to be $10,000 per year, and maintenance expenses for the Orion machine, $10,000 per year. Annual property tax of $10,000 and real estate tax of $14,000 would not change, but the workers' compensation tax would increase from $8,000 to $10,000 yearly. Insurance for the building was $12,000 per year and unlikely to change. Utilities (water, gas, electricity, and telephone) were $71,400 annually, but the Orion machine would add $15,000 to those costs. The accountant also told Vincent that it would be appropriate to charge to the Orion machine 15 per cent of common expenses (such as depreciation on the building, taxes, insurance for the current building, and utilities). General administrative expenses were unlikely to change due to the purchase of the Orion machine, but Terrell could still charge 10 per cent of those expenses to the Orion machine. Jobs completed on the Orion machine would be further processed in four subsequent processes: deburr; grind; inspect; and stamp, wash, wrap, and ship. The hourly cost for these processes for a job produced on the Orion machine would be as follows: deburr, $6.50; grind, $6.50; inspect, $2.25; and stamp, wash, wrap, and ship, $1.20. Vincent decided to run his calculations by a consultant. The consultant visited Terrell; understood the industry and Terrell's operations; talked to Vincent, his father, supervisors, and some workers; and studied the complete facility. He then asked Vincent and his father a series of questions (see Exhibit 3). CONSULTANT'S ASSUMPTIONS Based on the consultant's inquiry, the consultant changed some of Vincent's assumptions and added others. The consultant fairly assumed that the productive use of the Orion machine would be 90 per cent of the gross availability estimated by Vincent. The consultant also learned that the Orion machine could be operated by a skilled worker in each shift without any help from a semi-skilled worker. This arrangement implied that each skilled worker would work a 10-hour shift, including two hours of overtime every shift. The overtime hours would be paid a premium of 50 per cent of the base wage rate. The benefit rate would be applied to the regular wages and not to the wages paid for the overtime. Transportation of the Orion machine and its installation on Terrell's premises would cost $10,000. The new washing capacity and higher-capacity transformer would require an additional investment of $100,000. Terrell would also require additional working capital of $25,000 to support the additional sales coming from DPG's order. After the fifth year, the Orion machine would require an overhauling, which could cost as much as $50,000. The machine would likely then maintain its productivity for an additional five years, after which it would be scrapped at no net gain or loss. The insurance for the building and existing equipment was $12,000 per annum. The general insurance premium for the Orion machine, washing capacity, and transformer would be 2 per cent of the purchase price. The consultant estimated that the breakage and scrap of jobs would cost $1.20 per hour of work on the Orion machine. The consultant also proposed charging 20 per cent of the common expenses (including general administrative expenses) to the Orion machine rather than the 15 per cent estimated by Vincent Terrell had obtained a current loan at 6 per cent interest, but the new investments increased the perceived risk, so they would need to be financed through the bank at an interest rate of 9 per cent per annum. The consultant also advised Vincent that he and his father could attribute 12 per cent as a cost of owners' capital to the Orion machine, which had been set at 10 per cent. The consultant studied the owners' tax bracket and suggested that their marginal tax rate would be 35 per cent. The consultant was confident that DPG would agree to a proposal of being paid for the machine in equal monthly instalments over 48 months and that DPG would not charge interest on the outstanding amount. The consultant found Vincent's other assumptions to be in order. The consultant obtained the latest balance sheet of Terrell Manufacturing and prepared a projected balance sheet after factoring the proposal of purchasing the Orion machine and factoring all other assumptions. These balance sheets are provided in Exhibit 4. The consultant also prepared an Excel spreadsheet with the initial data and assumptions on one worksheet and calculated the full cost for pricing on another. The consultant then gave Vincent the detailed calculation of the hourly cost for processing the job order on the Orion machine and asked Vincent to submit that cost as the commercial bid for the Orion machine, along with the suggested lower limit for the hourly rate. The consultant also discussed the negotiation strategy with Vincent. EXHIBIT 3: CONSULTANT'S INQUIRY AND VINCENT PALOMBO'S RESPONSES Q. What would the customer pay in addition to the hourly rate of processing on the Orion machine? A. DPG would either provide the raw material or reimburse Terrell for the cost of raw material. We would include in the quote expenses incurred for the job work to go through other processes, such as deburring, grinding, inspection, and stamping/washing/wrapping/shipping. Q. Would there be any scrap or breakages during the processes? A. Oh yes, I did not think about that. We must provide for breakage and scrap. Q. Does the electric supply line have adequate capacity? A. I am sorry, I did not factor that in either. A higher capacity transformer must be installed at our cost. Q. What about the capacity in other processes to handle this additional job work? A. Deburring, grinding, and inspection capacity are enough, but washing capacity must be added. What about the inventory of consumable tools and other items? A. Additional inventory would be needed for handling the additional job. Q. How long would each machine would last? A. 10 years. Q. The Orion machine is old. Will it require any overhauling any time during its remaining life? A. Oh yes, the DPG manager did mention that such expenditure would be required at the end of five years from now. Q. What about training of workers and operators? A. DPG would train them and help with troubleshooting any problem with computerized components of the machines. Q. What about insurance and maintenance of the new machine? A. Yes, yes, that would add cost. Q. Q. A. Would utilities expenses increase with acquisition of these machines? I think so. Water charges, gas consumption, electricity consumption, as well as the telephone bill would increase. A. Q. You have estimated work of 100 hours per week, and two pairs of skilled and unskilled workers, which means you expect them to work for 50-hour weeks as opposed to a statutory 40-hour week. Would you not be required to pay overtime for 10 hours each week to each worker? You are right, I only calculated a 40-hour week, but to process DPG's job work, I need to work 50- hour week schedules per shift and two shifts a day. Each worker would work 10 hours a day. Thus, 10 hours per week will be paid the overtime premium of 50 per cent of the base rate. Q. How would other workers view the situation if you give two workers an opportunity to work 10 extra hours per week and make extra earnings? A. There should not be any problem because most departments work more than two normal shifts and almost all get opportunity to work more and earn more. Q. What about the cost of transportation and installation of machines? Yes, those costs must be provided. A. EXHIBIT 4: TERRELL MANUFACTURING'S BALANCE SHEET, AT THE END OF 2015 Before Purchasing After Purchasing Orion Orion Machine (Actual) Machine (Projected) Assets Current Assets Cash 44,215 44,215 Accounts Receivable 211,610 211,610 Inventory* 133,537 158,537 Total Current Assets 389,362 414,362 Property and Equipment, at Cost Building 500,000 500,000 Equipment** 196,987 496,987 Other Assets *** 15,210 25,210 Less: Accumulated Depreciation (11,179) (11,179) Net Property and Equipment 701,018 1,011,018 Total Assets 1,090,380 1,425,380 Liabilities and Owner Capital Current Liabilities Accounts Payable 198,918 198,918 Accrued Taxes 3,924 3,924 Working Capital Loan 25,000 Total Current Liabilities 202,842 227,842 Long-Term Debt Loan Payable**** 533,570 843,570 Loan Payable-Louis Palombo 62,358 62,358 Total Long-Term Loan 595,928 905,928 Owners' Capital Capital-Louis Palombo Capital-Vincent Palombo Draw-Louis Palombo Draw-Vincent Palombo Total Owners' Capital Total Liabilities and Owner Capital 174,695 174,695 (31,080) (26,700) 291,610 1,090,380 174,695 174,695 (31,080) (26,700) 291,610 1,425,380 Notes: "Amount equal to additional working capital loan is added in the current assets; **Costs of Orion machine and washing facility of $300,000 added here; ***Installation cost of $10,000 added to other assets as a miscellaneous asset; **** Includes bank loans of $310,000 ($10,000 for installation, $100,000 for washing facility, and $200,000 payable to DPG for Orion machine). Source: Company documents. vey Publishing W18526 TERRELL MANUFACTURING: BUYING A MACHINE Bhavesh Patel and Vincent Palombo wrote this case solely to provide material for class discussion. The authors do not intend to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a managerial situation. The authors may have disguised certain names and other identifying information to protect confidentiality. This publication may not be transmitted, photocopied, digitized, or otherwise reproduced in any form or by any means without the permission of the copyright holder. Reproduction of this material is not covered under authorization by any reproduction rights organization. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, contact Ivey Publishing, Ivey Business School, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, N6G ON1; (t) 519.661.3208; (e) cases@ivey.ca; www.iveycases.com. Copyright 2018, Ivey Business School Foundation Version: 2018-08-31 Terrell Manufacturing (Terrell) was a family-owned small business in Cleveland, Ohio. It supplied hydraulic manifoldspipe fittings with several lateral outlets to connect to other pipesfor the steel, plastics, and valve industry. Manifolds simplified the numerous connections, formerly provided by a series of hoses and tubes, resulting in an accurate and simple design. Demag Plastic Group (DPG), a large firm with global operations, had one facility near Terrell. DPG produced manifolds for its own use and also purchased manifolds from Terrell for additional requirements. DPG was Terrell's most important customer, providing more than 30 per cent of Terrell's revenue. Toward the end of 2015, DPG decided to stop producing manifolds and approached Terrell with a proposal: Terrell could buy DPG's Giddings & Lewis (G&L) Orion Machining Center (the Orion machine) and use it to process what would be additional orders from DPG. DPG would pay a 10 per cent markup on Terrell's approved cost to process DPG's orders. TERRELL MANUFACTURING Terrell Manufacturing was established by George Terrell in 1954. In its early years, the company provided manifolds primarily for the steel industry. The steel industry was growing at that time, resulting in strong growth for Terrell. Terrell added the plastics industry to its portfolio in the early 1960s, when Van Dorn Corporation (Van Dorn), a Cleveland-based producer of plastic moulding machines, began to use hydraulic manifolds as a replacement for its current system of hoses and tubes. Van Dorn gave the order for its manifold requirements to Terrell, creating Terrell's first market diversification. As a result of its efficient work, Terrell soon became well-known in the plastics industry for its ability to produce complex, high-quality manifolds. As the plastics industry flourished in the 1970s, Terrell grew again. By then, Terrell had large machines capable of machining manifolds of up to 10,000 pounds (4.5 metric tons). In early 1994, Van Dorn purchased an Orion machine and began producing manifolds in its own facility. The Orion machine was a technological feat in its ability to produce manifolds at speeds three to four times faster than conventional equipment. As a result, Terrell lost more than a quarter of its business. When George Terrell died in 1996, he left his business to his three daughters, none of whom was active in the company. Louis Palombo was acting as president of Terrell at that time. For nearly a decade, Terrell remained stagnant without any major decision or initiativeno new investment, no marketing, and no strategic plan. Key personnel began to leave, and overall sales declined from a high of US$3.5 million' in 1994 to $2.1 million in 2004. In December 2004, Palombo bought Terrell. By then, Vincent, Palombo's son, was also working for Terrell. For the year ending December 2004, Terrell achieved profits of $44,000 based on sales of $2.1 million. The company had 17 employeesthree in management positions and 14 in production activity. As the new owner, Palombo purchased a DeVlieg boring mill, fully retrofitted it at some cost, and placed it into production in March 2005. The DeVlieg boring mill became the most accurate and modern machining equipment in Terrell's facility (see Exhibits 1 and 2). THE OPPORTUNITY Van Dorn became Demag Plastic Group (DPG) after it was bought by a German firm in 2002. The new management continuously reviewed the company's operations and strategies to improve profitability and focus on the main business. At one stage, management decided to shut down the company's manifold operation and outsource the manifolds from a reliable supplier. They naturally thought of Terrell, which was already supplying DPG and was nearby. DPG approached Palombo and Vincent in December 2015, inviting them to bid on DPG's line of hydraulic manifolds, with an annual use that translated to sales of approximately $500,000 Terrell did not have enough capacity to meet DPG's total requirements without reducing Terrell's other customer base. When this limitation was expressed, DPG made an additional offer: DPG would sell its 20-year-old Orion machine to Terrell at an upfront cost of $200,000. DPG was open to negotiating the terms of payment, if doing so would help Terrell. The Orion machine would replace Terrell's initial two processes (see Exhibits 1 and 2), and Terrell would use its existing machines for the remaining processes needed to complete the manifolds made on the Orion machine for DPG. DPG asked Terrell to establish the base hourly rate for processing DPG's orders on the Orion machine and on Terrell's existing equipment. DPG would then discuss and negotiate the markup to determine the hourly rate that it would pay to Terrell. The offer came with one condition: Terrell could not use the spare capacity of the Orion machine to process orders for DPG's competitors. DPG was also concerned about Terrell's capabilities because of the significant technological skills required to operate the Orion machine. DPG, therefore, offered to train Terrell's selected operators and help with troubleshooting should the need arise, all free of cost. If everything went well for both companies, DPG would be willing to offer its second Orion machine to Terrell at some later date. Vincent thought this offer represented a great opportunity. The technological advancement, backed by an experienced multinational customer such as DPG, could give Terrell an additional advantage over its competitors. Vincent began calculating the hourly cost of processing on the Orion machine, so he would have a base for negotiating the rate. VINCENT'S ASSUMPTIONS After investigating the costs and issues, and discussing them with his father, Vincent concluded that the Orion machine could be used for 100 hours per week and 50 weeks per year. This usage implied two shifts of operations every day for five days a week and 50 weeks a year. One skilled worker and one semi-skilled worker would be required on each shift to operate the machine. A skilled worker would be paid $20 per hour and an semi-skilled worker, $15 per hour. Employee benefits could be calculated as an additional 30 per cent on employees' hourly wages. Vincent's accountant told him that the depreciable value of Terrell's building was $500,000. The Orion machine had a remaining life of 10 years. These assets could be depreciated on a straight-line basis at a rate of 10 per cent. Additional tooling expenses were expected to be $10,000 per year, and maintenance expenses for the Orion machine, $10,000 per year. Annual property tax of $10,000 and real estate tax of $14,000 would not change, but the workers' compensation tax would increase from $8,000 to $10,000 yearly. Insurance for the building was $12,000 per year and unlikely to change. Utilities (water, gas, electricity, and telephone) were $71,400 annually, but the Orion machine would add $15,000 to those costs. The accountant also told Vincent that it would be appropriate to charge to the Orion machine 15 per cent of common expenses (such as depreciation on the building, taxes, insurance for the current building, and utilities). General administrative expenses were unlikely to change due to the purchase of the Orion machine, but Terrell could still charge 10 per cent of those expenses to the Orion machine. Jobs completed on the Orion machine would be further processed in four subsequent processes: deburr; grind; inspect; and stamp, wash, wrap, and ship. The hourly cost for these processes for a job produced on the Orion machine would be as follows: deburr, $6.50; grind, $6.50; inspect, $2.25; and stamp, wash, wrap, and ship, $1.20. Vincent decided to run his calculations by a consultant. The consultant visited Terrell; understood the industry and Terrell's operations; talked to Vincent, his father, supervisors, and some workers; and studied the complete facility. He then asked Vincent and his father a series of questions (see Exhibit 3). CONSULTANT'S ASSUMPTIONS Based on the consultant's inquiry, the consultant changed some of Vincent's assumptions and added others. The consultant fairly assumed that the productive use of the Orion machine would be 90 per cent of the gross availability estimated by Vincent. The consultant also learned that the Orion machine could be operated by a skilled worker in each shift without any help from a semi-skilled worker. This arrangement implied that each skilled worker would work a 10-hour shift, including two hours of overtime every shift. The overtime hours would be paid a premium of 50 per cent of the base wage rate. The benefit rate would be applied to the regular wages and not to the wages paid for the overtime. Transportation of the Orion machine and its installation on Terrell's premises would cost $10,000. The new washing capacity and higher-capacity transformer would require an additional investment of $100,000. Terrell would also require additional working capital of $25,000 to support the additional sales coming from DPG's order. After the fifth year, the Orion machine would require an overhauling, which could cost as much as $50,000. The machine would likely then maintain its productivity for an additional five years, after which it would be scrapped at no net gain or loss. The insurance for the building and existing equipment was $12,000 per annum. The general insurance premium for the Orion machine, washing capacity, and transformer would be 2 per cent of the purchase price. The consultant estimated that the breakage and scrap of jobs would cost $1.20 per hour of work on the Orion machine. The consultant also proposed charging 20 per cent of the common expenses (including general administrative expenses) to the Orion machine rather than the 15 per cent estimated by Vincent Terrell had obtained a current loan at 6 per cent interest, but the new investments increased the perceived risk, so they would need to be financed through the bank at an interest rate of 9 per cent per annum. The consultant also advised Vincent that he and his father could attribute 12 per cent as a cost of owners' capital to the Orion machine, which had been set at 10 per cent. The consultant studied the owners' tax bracket and suggested that their marginal tax rate would be 35 per cent. The consultant was confident that DPG would agree to a proposal of being paid for the machine in equal monthly instalments over 48 months and that DPG would not charge interest on the outstanding amount. The consultant found Vincent's other assumptions to be in order. The consultant obtained the latest balance sheet of Terrell Manufacturing and prepared a projected balance sheet after factoring the proposal of purchasing the Orion machine and factoring all other assumptions. These balance sheets are provided in Exhibit 4. The consultant also prepared an Excel spreadsheet with the initial data and assumptions on one worksheet and calculated the full cost for pricing on another. The consultant then gave Vincent the detailed calculation of the hourly cost for processing the job order on the Orion machine and asked Vincent to submit that cost as the commercial bid for the Orion machine, along with the suggested lower limit for the hourly rate. The consultant also discussed the negotiation strategy with Vincent. EXHIBIT 3: CONSULTANT'S INQUIRY AND VINCENT PALOMBO'S RESPONSES Q. What would the customer pay in addition to the hourly rate of processing on the Orion machine? A. DPG would either provide the raw material or reimburse Terrell for the cost of raw material. We would include in the quote expenses incurred for the job work to go through other processes, such as deburring, grinding, inspection, and stamping/washing/wrapping/shipping. Q. Would there be any scrap or breakages during the processes? A. Oh yes, I did not think about that. We must provide for breakage and scrap. Q. Does the electric supply line have adequate capacity? A. I am sorry, I did not factor that in either. A higher capacity transformer must be installed at our cost. Q. What about the capacity in other processes to handle this additional job work? A. Deburring, grinding, and inspection capacity are enough, but washing capacity must be added. What about the inventory of consumable tools and other items? A. Additional inventory would be needed for handling the additional job. Q. How long would each machine would last? A. 10 years. Q. The Orion machine is old. Will it require any overhauling any time during its remaining life? A. Oh yes, the DPG manager did mention that such expenditure would be required at the end of five years from now. Q. What about training of workers and operators? A. DPG would train them and help with troubleshooting any problem with computerized components of the machines. Q. What about insurance and maintenance of the new machine? A. Yes, yes, that would add cost. Q. Q. A. Would utilities expenses increase with acquisition of these machines? I think so. Water charges, gas consumption, electricity consumption, as well as the telephone bill would increase. A. Q. You have estimated work of 100 hours per week, and two pairs of skilled and unskilled workers, which means you expect them to work for 50-hour weeks as opposed to a statutory 40-hour week. Would you not be required to pay overtime for 10 hours each week to each worker? You are right, I only calculated a 40-hour week, but to process DPG's job work, I need to work 50- hour week schedules per shift and two shifts a day. Each worker would work 10 hours a day. Thus, 10 hours per week will be paid the overtime premium of 50 per cent of the base rate. Q. How would other workers view the situation if you give two workers an opportunity to work 10 extra hours per week and make extra earnings? A. There should not be any problem because most departments work more than two normal shifts and almost all get opportunity to work more and earn more. Q. What about the cost of transportation and installation of machines? Yes, those costs must be provided. A. EXHIBIT 4: TERRELL MANUFACTURING'S BALANCE SHEET, AT THE END OF 2015 Before Purchasing After Purchasing Orion Orion Machine (Actual) Machine (Projected) Assets Current Assets Cash 44,215 44,215 Accounts Receivable 211,610 211,610 Inventory* 133,537 158,537 Total Current Assets 389,362 414,362 Property and Equipment, at Cost Building 500,000 500,000 Equipment** 196,987 496,987 Other Assets *** 15,210 25,210 Less: Accumulated Depreciation (11,179) (11,179) Net Property and Equipment 701,018 1,011,018 Total Assets 1,090,380 1,425,380 Liabilities and Owner Capital Current Liabilities Accounts Payable 198,918 198,918 Accrued Taxes 3,924 3,924 Working Capital Loan 25,000 Total Current Liabilities 202,842 227,842 Long-Term Debt Loan Payable**** 533,570 843,570 Loan Payable-Louis Palombo 62,358 62,358 Total Long-Term Loan 595,928 905,928 Owners' Capital Capital-Louis Palombo Capital-Vincent Palombo Draw-Louis Palombo Draw-Vincent Palombo Total Owners' Capital Total Liabilities and Owner Capital 174,695 174,695 (31,080) (26,700) 291,610 1,090,380 174,695 174,695 (31,080) (26,700) 291,610 1,425,380 Notes: "Amount equal to additional working capital loan is added in the current assets; **Costs of Orion machine and washing facility of $300,000 added here; ***Installation cost of $10,000 added to other assets as a miscellaneous asset; **** Includes bank loans of $310,000 ($10,000 for installation, $100,000 for washing facility, and $200,000 payable to DPG for Orion machine). Source: Company documentsStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started