This questions is based on the article, "The pandemic could give way to an era of rapid productivity growth," (https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2020/12/08/the-pandemic-could-give-way-to-an-era-of-rapid-productivity-growth) published by The Economist on December 8, 2020. "Coursehero doesn't allow me to post the article here!" The article discusses the prospects of long-term economic growth after the COVID-19 pandemic subsides.

(a)According to the article, some experts on productivity trends seem to be pessimistic about the prospects of productivity growth in the coming years, especially in the wake of the current pandemic. What is the basis of such pessimism? Discuss what the article says about the reasons and evidence offered by the pessimists.

(b)The article claims that "productivity is the magic elixir of economic growth". What does this statement mean? Based on what you have learned in this course and from the article, what would happen to per capita GDP growth in the long run if labor and capital increase, but there is no technological progress? Why? Please explain your answer.

(c)The data presented in the article suggests that productivity growth in developed countries has declined after the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 compared to the 1990s and the first half of 2000s. As the article points out, a major "question is why new technologies like improved robotics, cloud computing and artificial intelligence have not prompted more investment and higher productivity growth." The article examines three hypotheses that contend to explain this puzzle. What is the first hypothesis noted in the article? How plausible is this hypothesis in explaining the decline in productivity despite the advent of new technologies?

(d)What is the second hypothesis mentioned by the article as a potential explanation for productivity slow down despite the new technologies? How plausible is this hypothesis?

(e)What is the third hypothesis mentioned by the article as a potential explanation for productivity slow down despite the new technologies? How plausible is this hypothesis?

(f)The article claims that the pandemic in 2020 has quickened the pace of technology adoption and may bring about a period of rapid productivity growth. What is the evidence behind the claim that the exigencies of hard times may create opportunities for rapid change in later years? What examples of such a phenomenon are mentioned? How may the process work? What roles can governments play in ensuring that the potential productivity is realized?

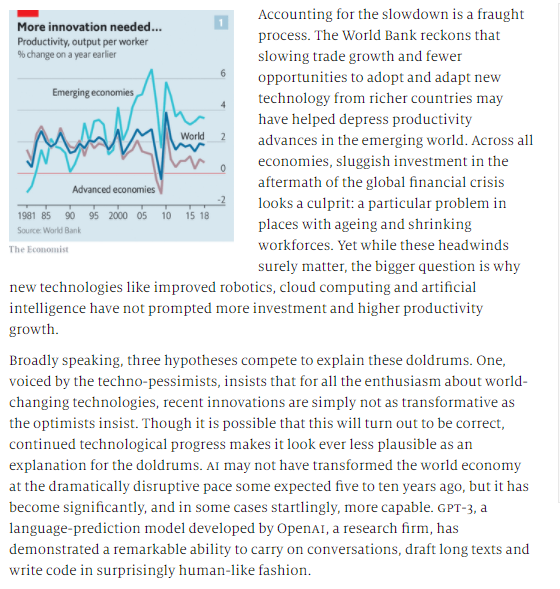

1-] E PRosPEcrs for a productivity resurgence may seem grim. After alL the T past decade has featured plenty of technological fatalism: in am; Peter Thiel, a venture capitalist, mused of the technological advances of the moment that "we wanted ying cars; instead we got 14o characters". Robert Gordon of Northwestern University has echoed this sentiment, speculating that humanity might never again invent something so transform ative as the flush toilet. Throughout the decade, data largely supported the views of the pessimists. Listen to this story I lull} \"1:00 -> Enjoy more audio and podcasts on iO_S or Android. What is more, some studies of past pandemics and analyses of the economic effects of this one suggest that covid-ig might make the productivity performance worse. According to research by the World Bank, countries struck by pandemic outbreaks in the 21st century [not including covid} experienced a marked decline in labour productivity of 9% after three years relative to unaffected countries. And yet, stranger things have happened. The brutal years of the logos were followed by the most extraordinary economic boom in history. A generation ago economists had nearly abandoned hope of ever matching the post-war performance when a computer-powered productivity explosion took place. And today there are tantalising hints that the economic and social traumas of the rst two decades of this century may soon give way to a new period of economic dynamism. Productivity is the magic elixir of economic growth. increases in the size of the labour force or the stock of capital can raise output, but the effect of such contributions diminishes unless better ways are found to make use of those resources. Productivity growthwringing more output from available resources is the ultimate source of long-run increases in incomes. It's not everything, as Paul Krugman, a Nobel economics laureate, once noted, but in the long run it's almost everything. Economists know less about how to boost productivity than they would like, however. increases in labour productivity {that is, more output per worker per hour} seem to follow improvements in educational levels, increases in investment {which raise the level of capital per worker}, and adoption of new innovations. a rise in total factor productivityor the efciency with which an economy uses its productive inputsmay require the discovery of new ways of producing goods and services, or the reallocation of scarce resources from low- productivity rms and places to high-productivity ones. Globally, productivity growth decelerated sharply in the igyos from scorchingly high rates in the post-war decades. A burst of higher productivity growth in the rich world, led by America, unfolded from the mid-logos into the early aooos. Emerging markets, too, enjoyed rapid productivity growth in the decade prior to the global nancial crisis, powered by high levels of investment and an expansion of trade which brought more sophisticated techniques and technologies to the developing-economy participants in global supply chains. Since the crisis, however, a broad-based and stubbornly persistent slowdown in productivity growth has set in [see chart 1}. About row: of the world's economies have been affected, according to the World Bank. Accounting for the slowdown is a fraught mm\" process. The 1|lilorld Bank reckons that *err-r slowing trade growth and fewer '- opportunities to adopt and adapt new ammo- technology from richer countries may have helped depress productivity . i. - . N} i'. -. W 3 advances in the emerging world. Across all m m . economies, sluggish investment in the 'r aftermath of the global nancial crisis ' looks a culprit: a particular problem in 1581 35 ill '35 an (IE Ill 15 It . . . . 5 HM places wrth ageing and shr1nlong n\" ,,,_,,,,,,,,. workforce s. 1ii'et while these headwinds surely matter, the bigger question is why new technologies like improved robotics, cloud computing and articial intelligence have not prompted more investment and higher productivity growth. Broadly speaking, three hypotheses compete to explain these doldrums. Dne, voiced by the tee hno-pessimists, insists that for all the enthusiasm about world- changing technologies, recent innovations are simply not as transformative as the optimists insist. Though it is possible that this will turn out to be correct, continued technologicai progress makes it look ever less plausible as an explanation for the doldrurns. A: may not have transformed the world economy at the dramatically disruptive pace some expected ve to ten years ago, but it has become signicantly, and in some cases startlingly, more capable. EFT-3, a la nguage-prediction model developed by Opens}, a research rm, has demonstrated a remarkable ability to carry on conversations, draft long texts and write code in surprisingly human-like fashion. Though the potential of the web to support an economy in which the constraints of distance do not bind has long underwhelmed, cloud computing and video- conferencing proved their economic worth over the past year, enabling vast amounts of productive activity to continue with scarcely an interruption despite the shuttering of many ofce s. New technologies are clearly able to do more than has generally been asked of them in recent years. That strengthens the case for a second explanation for slow productivity growth: chronically weak demand. In this view, expressed most vociferously by Larry Summers of Harvard University, governments' inability to stoke enough spending constrains investment and growth. More public investment is needed to unlock the economy's potential. Chronically low rates of interest and ination, limp private investment and lacklustre wage growth since the turn of the millennium clearly indicate that demand has been inadequate for most of the past two decades. Whether this meaningfully undercuts productivity growth is difcult to say. But in the years before the pandemic, as unemployment fell and wage growth ticked up; American labour productivity growth appeared to be accelerating: from an annual increase ofjusto.3% in son\": to a rise of 1.3% in song}: the fastest pace of growth since aoio. But a third explanation provides The strongest case for optimism: it takes time to work out how to use new technologies effectively. Al is an example of what economists call a "general-purpose technology", like electricity, which has the potential to boost productivity across many industries. But making best use of such technologies takes time and experimentation. This accumulation of know how is really an investment in "intangible capi tal". Recent work by Erik Brynjolfsson and Daniel Rock, of MIT, and Chad Syverson, of die University of Chicago, argues that this pattern leads to a phenomenon they call the "p roductivity J-curve". As new technologies are rst adopted, rms shift resources towards investment in intangibles: developing nev.r business processes. This shift in resources means that rm output suffers in a way that can not be fully explained by shifts in the measured use of labour and tangible capital, and which is thus interpreted as a decline in productivity growth. later, as intangible investments bear fruit, measured productivity surges because output rockets upward in a manner unexplained by measured inputs of labour and tangible capital. Back in mm, the failure to account for intangible investment in software made little difference to the productivity numbers, the authors reckon. But productivity has increasingly been understated; by the end of aoi, productivity growth was probably about or; percentage points higher than ofcial estimates suggested. This pattern has occurred before. In 193? Robert Solow, another Nobel prizewinner, remarked that computers could be seen everywhere except the productivity statistics. Nine years later American productivity growth began an acceleration which evoked the golden age of the 19 5os and 19 Eos. These processes are not always sexy. In the late 199os, the soaring share prices of internet startups hogged the headlines. The llip to productivity growth had other sources, like improvements in manufacturi ng techniques, better inventory managementand rationalisation of logistics and production processes made possible by the digitisation of rm records and the deployment of clever software. The Jcurve provides a way to reconcile mar\"l mirth\"!!! El tech optimism and adoption of new mmwmn technologies with lousy productivity on in I W I} no statistics. The role of intangible investments in unlocking the potential of new technologies may also rnea n that the pandemic, despite its economic damage, has made a productivity boom more likely to develop. Ofce closures have forced rms to invest in digitisation and automation, or to make better use of existing investments. Old analogue habits could no longer be tolerated. Though it will not show up in any economic statistics, in zozo executives around the world invested in the organisational overhauls needed to make new \"In-m . 1 mmma 1., a.\" tec hnolog1es work effectively {see chart 2}. mm'.fli am Not all of these efforts will have led to productivity improvements But as covid 19 recedes, the rms which did trans form their activities will retain a nd build on 'tEiI new ways of doing things. The crisis forced change Early evidence suggests that some transformations are very likely to stick, and that the pandemic quickened 'lf.' pace of technology adoption. A survey of global rms conducted by the World Economic FDI'LIIII this year found that more than SCH-E: of employers intend to accelerate plans to digitise diei r processes and provide more opportunities for remote work, while 5o% plan to accelerate automation of production tasks. About 43% expect changes like these to gene rate a net reduction in their workforces: a development which could pose labour- market challenges but which almost by denition implies improvements in productivity 11.. Inuuu-pu The crisis forced change Early evidence suggests that some transformations are very likely to stick, and mat the pandemic quickened me pace of technology adoption. A survey of global rms conducted by the 1i.l'il'orld Economic Forum this year found that more than Eo'l of employers intend to accelerate plans to d igitise their processes and provide more opportunities for remote work, while 5o% plan to accelerate automation of production tasks. About 43% expect changes like these to generate a net reduction in their workforces: a development which could pose labour market challenges but which almost by denition implies improvements in productivity. Harder to assess is the possibility mat the movement of so much work into me cloud could have productivityboosti ng effects for national economies or at the global level. High housingand property costs in rich, productive cities have locked m'rs and workers out of places where they might have done more with less resources. If tech workers can more easily contribute to top rms while living in affordable cities away from America's coasts, say, then strict zoning rules in the bay area of California will become less of a bottleneck. Ofce space in San Francisco or London freed up by increases in remote work could be occupied by firms which really do need their workers to operate in close physical proximity. Beyond that, and politics permitting, the boost to disia nce education and telemedicine delivered by the pandemic could help drive a period of growth in services trade, and the achievement of economies of scale in sectors which have long proved resistant to productivity-boosting measures None of this can be taken for granted. Making the most of new privatesector investments in technology and knowhow will require governments to engineer a rapid recovery in demand, to make complementary investments in public goods like broadband, and to focus on tackling the educational shortfalls so many students have suffered as a consequence of school closures But the raw materials for a new productivity boom appear to be falling into place, in a way not seen for at least two decades. This year's darkness may in fact mean that dawn is just over the horizon