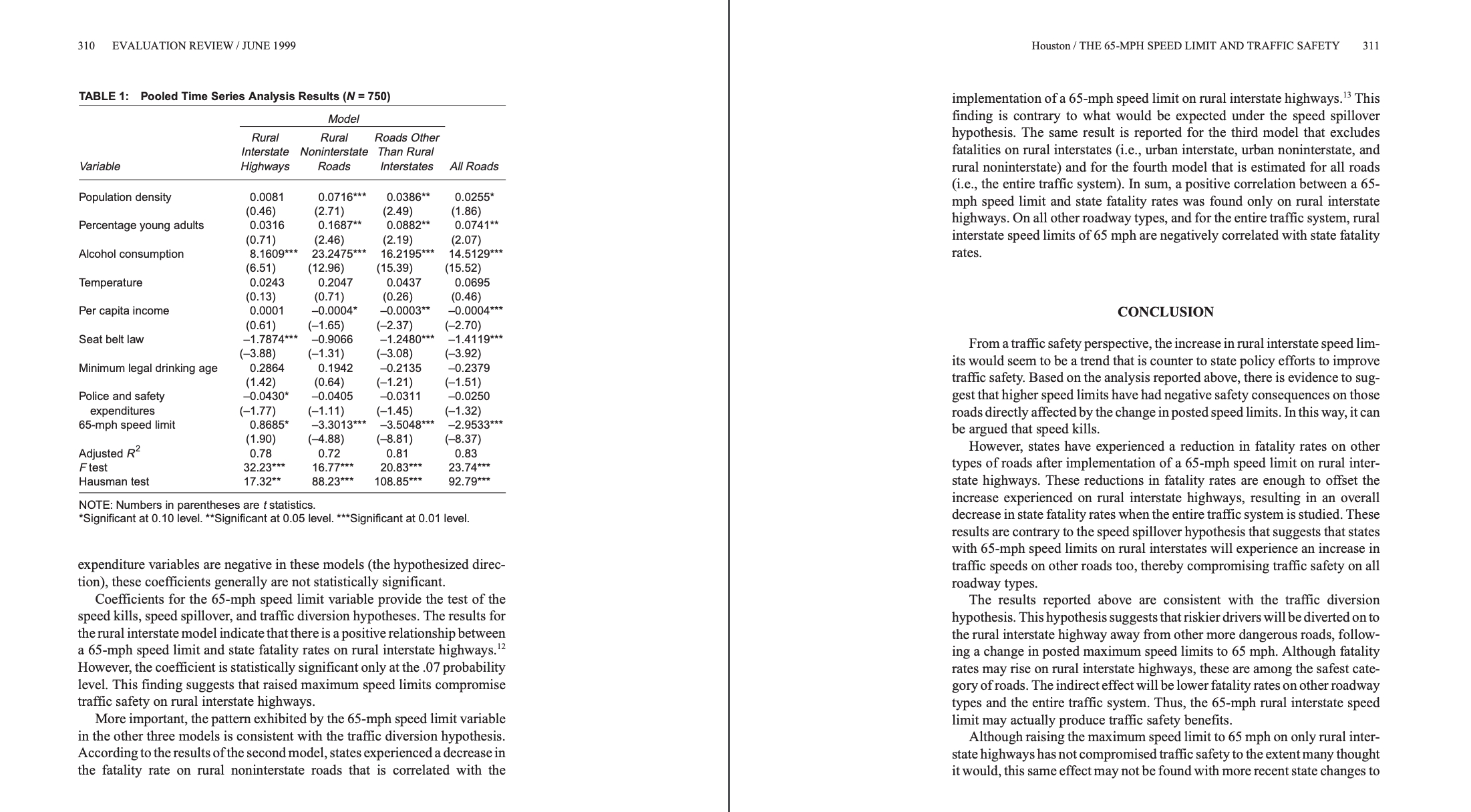

Question: This study evaluates the impact of the 65-mph speed limit on traffic safety. Using data for the categories of roads: rural interstate highways, rural noninterstate

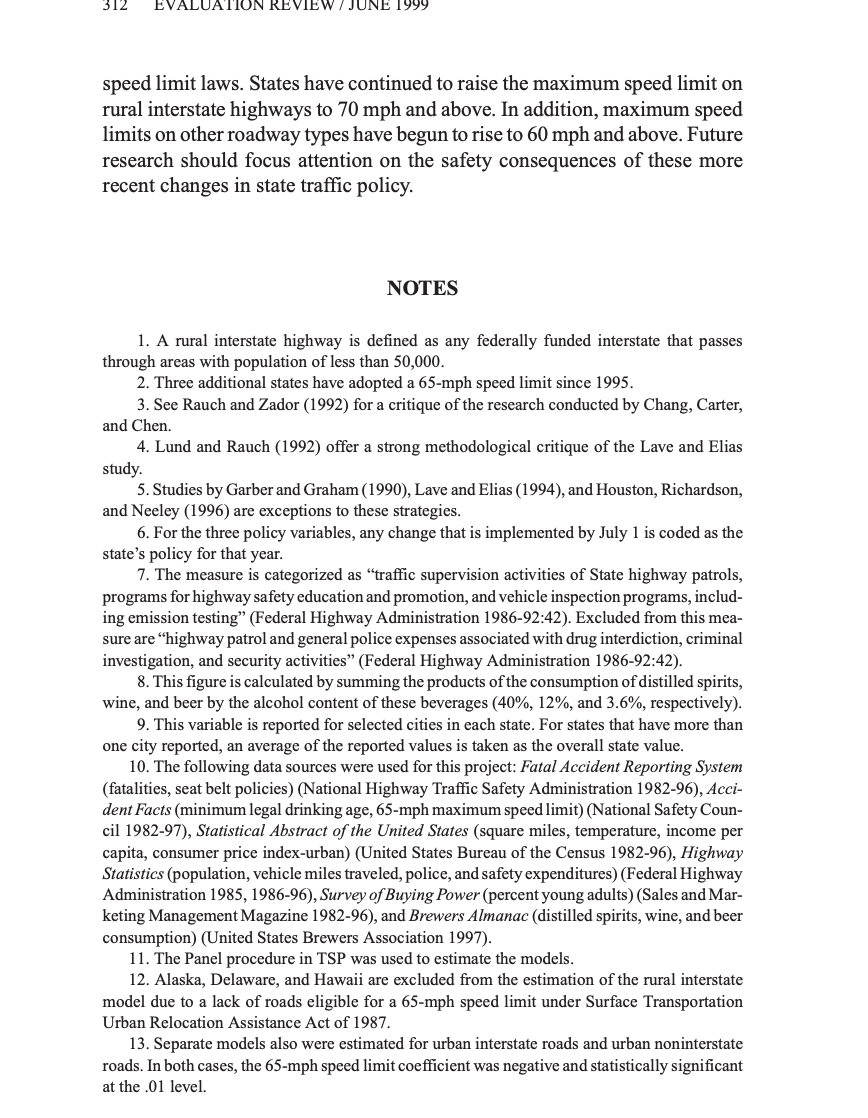

This study evaluates the impact of the 65-mph speed limit on traffic safety. Using data for the categories of roads: rural interstate highways, rural noninterstate roads, all years 1981 to 1995 for all 50 states, a pooled time series analysis is conducted. Separate models roads except for rural interstate highways, and all roads. Fatality data for all are estimated for state fatality rates on four categories of roads: rural interstate highways, rural noninterstate roads, all roads except for rural interstate highways, and all roads. It is reported 50 states for the years 1981 to 1995 were obtained from the Fatal Accident that the 65-mph speed limit increased fatality rates on rural interstate highways but was corre- Reporting System (FARS) data set. The models estimate the relationship lated with a reduction in state fatality rates on the three other categories of roads. between 65-mph speed limits and state fatality rates, controlling for other traffic safety policies and general state characteristics. IMPLICATIONS OF THE 65-MPH SPEED LITERATURE REVIEW LIMIT FOR TRAFFIC SAFETY In response to gasoline shortages that were attributed to an Arab oil embargo, the federal government mandated a maximum national speed limit DAVID J. HOUSTON of 55 mph in 1974. To ensure implementation of this federal policy through University of Tennessee the states, the U.S. Department of Transportation was directed to withhold highway funds from states that did not adopt the 55-mph speed limit (Baum, Lund, and Wells 1989). Although the primary goal was gasoline conserva- What impact do higher maximum speed limits have on traffic safety? This tion, by reducing the number of fatalities sustained in motor vehicle crashes is an important social policy question, given the recent trend toward higher the 55-mph limit was credited with enhancing traffic safety (Meier and Mor- state speed limits. States were permitted to raise the maximum speed limit on gan 1981; National Research Council 1984; Kamerud 1988; Chirinko and rural interstate highways with the enactment of the Surface Transportation Harper 1993). Urban Relocation Assistance (STURA) Act in 1987. In the year following In recent years, the federal government has reversed its position relating to STURA, 39 states adopted a 65 miles per hour (mph) speed limit, followed by a national speed limit and has returned this regulatory authority back to the B additional states in the years since (National Safety Council 1982-97). Con- states. With the enactment of the Surface Transportation and Uniform Relo- ventional wisdom suggests that higher speed limits pose an increased hazard cation Assistance Act of 1987, states were permitted to increase speed limits to public safety. If this were the case, then the trend toward higher speed lim- on rural interstate highways up to a maximum of 65 mph. ' Thirty-nine states its is contrary to state efforts to improve traffic safety through other policies. adopted a 65-mph speed limit on eligible roads during 1987, and by the end of Several studies reinforce the conventional wisdom that speed kills, report- 1995, this collection of states grew to 45 in number (National Safety Council ing that fatalities on rural interstate highways have increased after posting 1982-97).2 On December 8, 1995, the national maximum speed limit was 65-mph speed limits. In contrast, Lave and Elias (1994) argue that higher abolished with the enactment of the National Highway System Designation speed limits on rural interstates have reduced overall state fatality rates. Act. This act returned authority to the states to set speed limits on all roads. Faster traffic will be diverted to roads with posted limits of 65 mph, making By the end of 1997, 27 states had raised their maximum speed limit to at least other roads safer to drive. A significant amount of research has contributed to 70 mph (National Safety Council 1982-97). Although speed limits of 70 mph this debate, but most scholars study an individual state or aggregate several and 75 mph pose additional concerns for traffic safety, the analysis presented states together into a common time series. below focuses on the impact of the 65-mph speed limit because of data The pooled time series analysis reported below contributes to the debate limitations. over the 65-mph speed limit by examining the individual experience of all 50 Opponents of the 65-mph speed limit cite safety concerns, arguing that states in one common analysis. To provide a direct test of the hypothesis higher speed limits result in an increased number of motor vehicle fatalities offered by Lave and Elias (1994), separate models were estimated for four (Kaye, Mulrine, and Wu 1995). This argument is based on the "speed kills" hypothesis. This hypothesis states that higher speeds reduce the amount of S EVALUATION REVIEW, Vol. 23 No. 3, June 1999 304-315 1999 Sage Publications, Inc. time a driver has to correct for an error in judgment or adjust to an unexpected 304306 EVALUATION REVIEW / JUNE 1999 Houston / THE 65-MPH SPEED LIMIT AND TRAFFIC SAFETY 307 obstacle, which increases the severity of a crash (Bowie and Walz 1994; Gar- contend that their study provides a more accurate assessment of the safety ber and Graham 1990; Moore, Dolinis, and Woodward 1995). An additional effects of the 65-mph speed limit than do other studies because of their focus argument against higher maximum speed limits is the "speed spillover" on fatality rates (not number of fatalities) and systemwide experience ( not the hypothesis that contends that higher speed limits on rural interstates pose experience of only roads with changes in posted speed)." A negative correla- additional hazards for other roadway types (Garber and Graham 1990). tion between the 65-mph speed limit and total fatality rates was reported in a Motorists traveling at higher speeds on rural interstate highways will get in pooled time series analysis of all 50 states (Houston, Richardson, and Neeley the habit of driving at these higher speeds and carry this behavior over to 1996). However, Mcknight, Klein, and Tippetts (1989) found no safety other roads (Kamerud 1988). benefits on other roads attributable to a 65-mph speed limit on rural In contrast, the "traffic diversion" hypothesis suggests that higher rural interstates. interstate speed limits have beneficial effects for traffic safety. Under this The mixed findings that characterize this literature may be a function of hypothesis, faster traffic is diverted away from rural noninterstate roads to the several factors. First, evaluations often are conducted with only 1 or 2 years rural interstate highways that are better designed to accommodate faster traf- of postimplementation data. Second, many studies employ the number of fic (Kamerud 1988; Lave and Elias 1994). Although higher maximum speed fatalities as a dependent variable. The use of fatality rates would be more limits may result in more fatalities on rural interstates, traffic diversion pro- appropriate because it controls for the exposure to risk that is a function of the duces a reduction in the overall level of fatalities experienced by the entire amount of travel in a state. Third, either a single-state experience is exam- traffic system. ined, or many states that have adopted a 65-mph speed limit are grouped The findings from research evaluating higher maximum speed limits do together into a single time series (this latter strategy raises questions about not provide a clear indication as to which of these hypotheses best describes cross-level inference)." Fourth, other traffic safety policies or state character- the experience of the states. Aggregate analyses of the national experience by istics that are related to traffic safety are not controlled for in many of these Baum, Lund, and Wells (1989) and Baum, Wells, and Lund (1990, 1991) and studies. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (1989, 1992, 1998) indicate The analysis presented below will contribute to the literature evaluating significant increases in fatalities on rural interstates after the implementation the impact of the 65-mph speed limit by reporting the results of a pooled time of a 65-mph speed limit. Additional evidence of this negative impact on traf- series analysis for the 50 states. The advantage of this technique is that it esti- fic safety has been reported in multistate (Garber and Graham 1990; Godwin mates the relationship between higher speed limits and traffic safety by 1992) and single-state studies (Gallaher et al. 1989; Mccarthy 1994; Wage- examining each individual state experience. This methodological approach naar, Streff, and Schultz 1990). Furthermore, a rise in fatalities on roads not also permits the introduction of additional variables to control for other poli- eligible for the increased speed limit, indicative of speed spillover effects, cies and environmental factors related to traffic safety. Up to 9 years of post- also has been found (Garber and Graham 1990; Rock 1995). implementation data are examined for many of the states. Other single-state studies, however, report that traffic safety has not been compromised by higher maximum speed limits (Brown, Maghsoodloo, and McArdle 1990; Pant, Adhami, and Niehaus 1992; Pfefer, Stenzel, and Lee 1991; Sidhu 1990; Smith 1990). A similar finding was reported in a 5-state DATA AND METHODS study by Garber and Gadiraju (1992) and by Chang and Paniati (1990) in Pooled time series models are estimated below, using data from 1981 to their study of 32 states with 65-mph speed limits. In a similar 32-state study, 1995 for all 50 states. The dependent variables are state motor vehicle fatality Chang, Chen, and Carter (1993) report a statistically significant increase in rates, which are the number of fatalities per 1 billion vehicle miles of travel. rural interstate fatalities, but only in the first year after implementation of a The advantage of using fatality rates as the dependent variables is that they 65-mph speed limit.' control for the amount of travel or exposure to risk experienced in each state. Finally, Lave and Elias (1994) find support for the traffic diversion Fatality data from the FARS data set compiled by National Highway Traffic hypothesis in aggregate and individual analyses of 40 states that adopted 65- Safety Administration are used in creating these variables. To provide a test mph speed limits in 1987. They report a decrease in the total fatality rate for of both the traffic diversion and speed spillover hypotheses, separate models these states after implementation of the higher speed limit. Lave and Elias308 EVALUATION REVIEW / JUNE 1999 Houston / THE 65-MPH SPEED LIMIT AND TRAFFIC SAFETY 309 are estimated for fatality rates on each of four categories of roads: rural inter- In addition, a relationship between state climate and fatality rates has been state highways, rural noninterstate roads, all roads except for rural interstate reported (Evans 1991; Zlatoper 1991). To operationalize state climate, the highways, and all roads normal daily mean temperature for each state is employed and is expected to A state's speed limit is operationalized as a dummy variable that takes on be positively related to fatality rates." Several scholars contend that higher the value of 1 to represent a maximum speed limit of 65 mph on rural inter- income groups will have a greater demand for safety, thus hypothesizing a states and a 0 to represent a 55-mph speed limit." Based on the traffic diver- negative relationship between income and motor vehicle fatality rates (Chir- sion hypothesis, we expect that the 65-mph speed limit variable would be inko and Harper 1993; Legge and Park 1994). The income variable is mea- negatively related to state fatality rates on all types of roads except rural inter- sured as the income per capita (in 1982-1984 constant dollars) for each state. 10 state highways. Whereas under the speed spillover hypothesis, we expect the The findings reported below were estimated with a pooled time series rou- 65-mph speed limit variable to be positively related to fatality rates on roads tine assuming a fixed effects model." In a fixed effects model, the coeffi- that are connected to rural interstates (e.g., rural noninterstate roads). cients for the independent variables are assumed to be constant across each To control for the impact that other policies might have on traffic safety, cross-section, while each cross-section has a unique intercept (for this rea- variables for seat belt laws and minimum legal drinking ages are added to son, the 50 state intercepts are not reported below) (Hsaio 1986). The appro- these models. Seat belt laws are operationalized by using a dummy variable priateness of a fixed effects model for the data was determined with two sta- where 1 represents the presence of such a state law and 0 represents the tistical tests. First, an F test comparing an OLS regression on the entire absence of one. It is hypothesized that state fatality rates will decline in the sample versus a fixed effects model was conducted (the null hypothesis is that presence of a mandatory seat belt law (Asch et al. 1991; Houston, Richard- there is no difference between the OLS and fixed effects estimates). Second, a son, and Neeley 1995, 1996; Wagenaar, Maybee, and Sullivan 1988). The Hausman specification test compares a fixed effects model with a random minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) in a state is operationalized as the effects model that assumes unique coefficients for the independent variables youngest age that a person can obtain any form of alcohol. It is hypothesized for each cross-section (the random effects model is the null hypothesis) (Hall that higher MLDA's will result in lower state fatality rates (Houston, Richard- 1996). Both the F test and Hausman specification test indicate that the fixed son, and Neeley 1995, 1996; O'Malley and Wagenaar 1991; Saffer and effects model is appropriate for all of the models reported below. Grossman 1987). State government expenditures on police and safety func- tions can further influence traffic safety. States that spend more on enforce- ment should have a higher compliance with traffic laws and thereby have safer roads. Although it is difficult to measure enforcement directly, police FINDINGS and safety expenditures per capita (in 1982-1984 constant dollars) will serve The results of the pooled time series analysis for the four models are pre- as a proxy in this analysis. It is expected that there is a negative relationship sented in Table 1. Several of the control variables perform as expected across between police and safety expenditures and traffic fatality rates." the models. The percentage of young adults and per capita alcohol consump Several demographic, economic, and climatic control variables also are tion are positively related to state fatality rates. Per capita income is nega- included in the models. Population density, measured as population (in thou- tively related to fatality rates in three of the models, as hypothesized. How- sands) per square mile, has been found to be negatively associated with traffic ever, the temperature variable was found to be unrelated to fatality rates, and fatality rates (Baker, Whitfield, and O'Neill 1987; Houston, Richardson, and population density is related to these rates in a positive direction, the opposite Neeley 1995). To control for the proportion of young, inexperienced drivers of that hypothesized. in a state, the percentage of the adult population that falls in the 18 to 24 age Among the policy controls, seat belt laws are negatively related to state category is employed as a proxy. It is hypothesized that the percentage of fatality rates, a finding that is statistically significant in three of the four mod- young adults is positively related to state fatality rates (Chirinko and Harper els. This finding is consistent with previous studies that report improved traf- 1993; Zlatoper 1991). State alcohol consumption also is reported to be posi- fic safety in a state after the implementation of mandatory belt use laws. The tively related to motor vehicle fatality rates (Chirinko and Harper 1993; other two policy control variables do not perform as expected. Although most Legge and Park 1994), and it is measured as total consumption of alcohol in of the coefficients for the minimum legal drinking age, and police and safety gallons per capita.310 EVALUATION REVIEW / JUNE 1999 Houston / THE 65-MPH SPEED LIMIT AND TRAFFIC SAFETY 311 TABLE 1: Pooled Time Series Analysis Results (N = 750) implementation of a 65-mph speed limit on rural interstate highways." This Model finding is contrary to what would be expected under the speed spillover Rural Rural Roads Other hypothesis. The same result is reported for the third model that excludes Interstate Noninterstate Than Rural fatalities on rural interstates (i.e., urban interstate, urban noninterstate, and Variable Highways Roads Interstates All Roads rural noninterstate) and for the fourth model that is estimated for all roads (i.e., the entire traffic system). In sum, a positive correlation between a 65- Population density 0.0081 0.0716*** 0.0386** 0.0255* (0.46 (2.71) mph speed limit and state fatality rates was found only on rural interstate (2.49) (1.86) Percentage young adults 0.0316 0.1687** 0.0882** 0.0741** highways. On all other roadway types, and for the entire traffic system, rural (0.71) (2.46) (2.19) (2.07) interstate speed limits of 65 mph are negatively correlated with state fatality Alcohol consumption 8.1609*** 23.2475*** 16.2195*** 14.5129*** rates. (6.51) 12.96) 15.39) (15.52) Temperature 0.0243 0.2047 0.0437 0.0695 (0.13) (0.71) (0.26) (0.46 Per capita income 0.0001 -0.0004* -0.0003** -0.0004*** CONCLUSION (0.61) (-1.65) (-2.37 (-2.70 Seat belt law -1.7874*** -0.9066 -1.2480*** -1.4119*#* (-3.88) (-1.31) (-3.08) (-3.92) From a traffic safety perspective, the increase in rural interstate speed lim- Minimum legal drinking age 0.2864 0.1942 -0.2135 -0.2379 its would seem to be a trend that is counter to state policy efforts to improve (1.42) (0.64) -1.21) -1.51) traffic safety. Based on the analysis reported above, there is evidence to sug- Police and safety -0.0430* -0.0405 -0.0311 -0.0250 gest that higher speed limits have had negative safety consequences on those expenditures (-1.77) (-1.11) (-1.45) (-1.32) roads directly affected by the change in posted speed limits. In this way, it can 65-mph speed limit 0.8685* -3.3013*#* -3.5048*** -2.9533*** (1.90 (-4.88 -8.81) -8.37) be argued that speed kills. Adjusted R2 0.78 0.72 0.81 0.83 However, states have experienced a reduction in fatality rates on other F test 32.23*** 16.77*** 20.83** 23.74*#* types of roads after implementation of a 65-mph speed limit on rural inter- Hausman test 17.32** 88.23*** 108.85** 92.79*** state highways. These reductions in fatality rates are enough to offset the NOTE: Numbers in parentheses are t statistics. increase experienced on rural interstate highways, resulting in an overall *Significant at 0.10 level. **Significant at 0.05 level. ***Significant at 0.01 level. decrease in state fatality rates when the entire traffic system is studied. These results are contrary to the speed spillover hypothesis that suggests that states with 65-mph speed limits on rural interstates will experience an increase in expenditure variables are negative in these models (the hypothesized direc- traffic speeds on other roads too, thereby compromising traffic safety on all tion), these coefficients generally are not statistically significant. roadway types. Coefficients for the 65-mph speed limit variable provide the test of the The results reported above are consistent with the traffic diversion speed kills, speed spillover, and traffic diversion hypotheses. The results for hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that riskier drivers will be diverted on to the rural interstate model indicate that there is a positive relationship between the rural interstate highway away from other more dangerous roads, follow- a 65-mph speed limit and state fatality rates on rural interstate highways.2 ing a change in posted maximum speed limits to 65 mph. Although fatality However, the coefficient is statistically significant only at the .07 probability rates may rise on rural interstate highways, these are among the safest cate- level. This finding suggests that raised maximum speed limits compromise gory of roads. The indirect effect will be lower fatality rates on other roadway traffic safety on rural interstate highways. types and the entire traffic system. Thus, the 65-mph rural interstate speed More important, the pattern exhibited by the 65-mph speed limit variable limit may actually produce traffic safety benefits. in the other three models is consistent with the traffic diversion hypothesis. Although raising the maximum speed limit to 65 mph on only rural inter- According to the results of the second model, states experienced a decrease in state highways has not compromised traffic safety to the extent many thought the fatality rate on rural noninterstate roads that is correlated with the it would, this same effect may not be found with more recent state changes toEVA speed limit laws. States have continued to raise the maximum speed limit on rural interstate highways to 70 mph and above. In addition, maximum speed limits on other roadway types have begun to rise to 60 mph and above. Future research should focus attention on the safety consequences of these more recent changes in state traffic policy. NOTES 1. A rural interstate highway is defined as any federally funded interstate that passes through areas with population of less than 50,000. 2. Three additional states have adopted a 65-mph speed limit since 1995. 3. See Rauch and Zador (1992) for a critique of the research conducted by Chang, Carter, and Chen. 4. Lund and Rauch (1992) offer a strong methodological critique of the Lave and Elias study. 5. Studies by Garber and Graham (1990), Lave and Elias (1994), and Houston, Richardson, and Neeley (1996) are exceptions to these strategies. 6. For the three policy variables, any change that is implemented by July 1 is coded as the state's policy for that year. 7. The measure is categorized as "traffic supervision activities of State highway patrols, programs for highway safety education and promotion, and vehicle inspection programs, include ing emission testing" (Federal Highway Administration 1986-92:42). Excluded from this mea- sure are "highway patrol and general police expenses associated with drug interdiction, criminal investigation, and security activities" (Federal Highway Administration 1986-92:42). 8. This figure is calculated by summing the products of the consumption of distilled spirits, wine, and beer by the alcohol content of these beverages (40%, 12%, and 3.6%, respectively). 9. This variable is reported for selected cities in each state. For states that have more than one city reported, an average of the reported values is taken as the overall state value. 10. The following data sources were used for this project: Fatal Accident Reporting System (fatalities, seat belt policies) (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1982-96), Acci- dent Facts (minimum legal drinking age, 65-mph maximum speed limit) (National Safety Coun- cil 1982-97), Statistical Abstract of the United States (square miles, temperature, income per capita, consumer price index-urban) (United States Bureau of the Census 1982-96), Highway Statistics (population, vehicle miles traveled, police, and safety expenditures) (Federal Highway Administration 1985, 1986-96), Survey of Buying Power (percent young adults) (Sales and Mar- keting Management Magazine 1982-96), and Brewers Almanac (distilled spirits, wine, and beer consumption) (United States Brewers Association 1997). 11. The Panel procedure in TSP was used to estimate the models. 12. Alaska, Delaware, and Hawaii are excluded from the estimation of the rural interstate model due to a lack of roads eligible for a 65-mph speed limit under Surface Transportation Urban Relocation Assistance Act of 1987. 13. Separate models also were estimated for urban interstate roads and urban noninterstate roads. In both cases, the 65-mph speed limit coefficient was negative and statistically significant at the .01 level.EVA speed limit laws. States have continued to raise the maximum speed limit on rural interstate highways to 70 mph and above. In addition, maximum speed limits on other roadway types have begun to rise to 60 mph and above. Future research should focus attention on the safety consequences of these more recent changes in state traffic policy. NOTES 1. A rural interstate highway is defined as any federally funded interstate that passes through areas with population of less than 50,000. 2. Three additional states have adopted a 65-mph speed limit since 1995. 3. See Rauch and Zador (1992) for a critique of the research conducted by Chang, Carter, and Chen. 4. Lund and Rauch (1992) offer a strong methodological critique of the Lave and Elias study. 5. Studies by Garber and Graham (1990), Lave and Elias (1994), and Houston, Richardson, and Neeley (1996) are exceptions to these strategies. 6. For the three policy variables, any change that is implemented by July 1 is coded as the state's policy for that year. 7. The measure is categorized as "traffic supervision activities of State highway patrols, programs for highway safety education and promotion, and vehicle inspection programs, include ing emission testing" (Federal Highway Administration 1986-92:42). Excluded from this mea- sure are "highway patrol and general police expenses associated with drug interdiction, criminal investigation, and security activities" (Federal Highway Administration 1986-92:42). 8. This figure is calculated by summing the products of the consumption of distilled spirits, wine, and beer by the alcohol content of these beverages (40%, 12%, and 3.6%, respectively). 9. This variable is reported for selected cities in each state. For states that have more than one city reported, an average of the reported values is taken as the overall state value. 10. The following data sources were used for this project: Fatal Accident Reporting System (fatalities, seat belt policies) (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1982-96), Acci- dent Facts (minimum legal drinking age, 65-mph maximum speed limit) (National Safety Coun- cil 1982-97), Statistical Abstract of the United States (square miles, temperature, income per capita, consumer price index-urban) (United States Bureau of the Census 1982-96), Highway Statistics (population, vehicle miles traveled, police, and safety expenditures) (Federal Highway Administration 1985, 1986-96), Survey of Buying Power (percent young adults) (Sales and Mar- keting Management Magazine 1982-96), and Brewers Almanac (distilled spirits, wine, and beer consumption) (United States Brewers Association 1997). 11. The Panel procedure in TSP was used to estimate the models. 12. Alaska, Delaware, and Hawaii are excluded from the estimation of the rural interstate model due to a lack of roads eligible for a 65-mph speed limit under Surface Transportation Urban Relocation Assistance Act of 1987. 13. Separate models also were estimated for urban interstate roads and urban noninterstate roads. In both cases, the 65-mph speed limit coefficient was negative and statistically significant at the .01 level

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts