Question

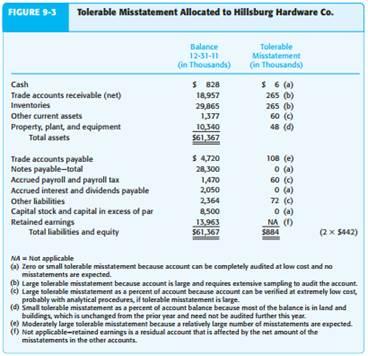

Required a. Use professional judgment in deciding on the preliminary judgment about materiality for earnings, current assets, current liabilities, and total assets. Your conclusions should

Required

a. Use professional judgment in deciding on the preliminary judgment about materiality for earnings, current assets, current liabilities, and total assets. Your conclusions should be stated in terms of percents and dollars.

b. Assume that you define materiality for this audit as a combined misstatement of earnings from continuing operations before income taxes of 5%. Also assume that you believe there is an equal likelihood of a misstatement of every account in the financial statements, and each misstatement is likely to result in an overstatement of earnings. Allocate materiality to these financial statements as you consider appropriate.

c. As discussed in part b, net earnings from continuing operations before income taxes was used as a base for calculating materiality for the Wexler Industries audit. Discuss why most auditors use before-tax net earnings instead of after-tax net earnings when calculating materiality based on the income statement.

d. Now, assume that you have decided to allocate 75% of your preliminary judgment to accounts receivable, inventories, and accounts payable because you believe all other accounts have a low inherent and control risk. How does this affect evidence accumu - lation on the audit?

e. Assume that you complete the audit and conclude that your preliminary judgment about materiality for current assets, current liabilities, and total assets has been met. The actual estimate of misstatements in earnings exceeds your preliminary judgment. What should you do?

(Objective 9-2)

SET PRELIMINARY JUDGMENT ABOUT MATERIALITY

Auditing standards require auditors to decide on the combined amount of misstatements in the financial statements that they would consider material early in the audit as they are developing the overall strategy for the audit. We refer to this as the preliminary judgment about materiality. It is called a preliminary judgment about materiality because, although a professional opinion, it may change during the engage ment. This judgment must be documented in the audit files. The preliminary judgment about materiality (step 1 in Figure 9-1) is the maximum amount by which the auditor believes the statements could be misstated and still not affect the decisions of reasonable users. (Conceptually, this is an amount that is $1 less than materiality as defined by the FASB. We define preliminary materiality in this manner for convenience.) This judgment is one of the most important decisions the auditor makes, and it requires considerable professional wisdom. Auditors set a preliminary judgment about materiality to help plan the appropriate evidence to accumulate. The lower the dollar amount of the preliminary judgment, the more evidence required. Examine the financial statements of Hillsburg Hardware Co., in the glossy insert to the textbook. What combined amount of misstatements will affect decisions of reasonable users? Do you believe that a $100 misstatement will affect users’ decisions? If so, the amount of evidence required for the audit is likely to be beyond that for which the management of Hillsburg Hardware is willing to pay. Do you believe that a $10 million misstatement will be material? Most experienced auditors believe that amount is far too large as a combined materiality amount in these circumstances. During the audit, auditors often change the preliminary judgment about materiality. We refer to this as the revised judgment about materiality. Auditors are likely to make the revision because of changes in one of the factors used to determine the preliminary judgment; that is because the auditor decides that the preliminary judgment was too large or too small. For example, a preliminary judgment about materiality is often deter - mined before year-end and is based on prior years’ financial statements or interim finan - cial statement information. The judgment may be reevaluated after current financial statements are available. Or, client circumstances may have changed due to qualitative events, such as the issuance of debt that created a new class of financial statement users. Several factors affect the auditor’s preliminary judgment about materiality for a given set of financial statements. The most important of these are: Materiality Is a Relative Rather Than an Absolute Concept A misstatement of a given magnitude might be material for a small company, whereas the same dollar misstatement could be immaterial for a large one. This makes it impossible to establish dollar-value guidelines for a preliminary judgment about materiality that are appli - cable to all audit clients. For example, a total misstatement of $10 million would be extremely material for Hillsburg Hardware Co. because, as shown in their financial statements, total assets are about $61 million and net income before taxes is less than $6 million. A misstatement of the same amount is almost certainly immaterial for a company such as IBM, which has total assets and net income of several billion dollars. Bases Are Needed for Evaluating Materiality Because materiality is relative, it is necessary to have bases for establishing whether misstatements are material. Net income before taxes is often the primary base for deciding what is material for profit-oriented busi nesses because it is regarded as a critical item of information for users. Some firms use a different primary base, because net income often fluctuates considerably from year to year and therefore does not provide a stable base, or when the entity is a not-forprofit organi zation. Other primary bases include net sales, gross profit, and total or net assets. After establishing a primary base, auditors should also decide whether the misstatements could materially affect the reasonableness of other bases such as current assets, total assets, current liabilities, and owners’ equity. Auditing standards require the auditor to document in the audit files the basis used to determine the preliminary judgment about materiality. Assume that for a given company, an auditor decided that a misstatement of income before taxes of $100,000 or more would be material, but a misstatement would need to be $250,000 or more to be material for current assets. It is not appropriate for the auditor to use a preliminary judgment about materiality of $250,000 for both income before taxes and current assets. Instead, the auditor must plan to find all misstatements affecting income before taxes that exceed the preliminary judgment about materiality of $100,000. Because almost all misstatements affect both the income statement and balance sheet, the auditor uses a primary preliminary materiality level of $100,000 for most tests. The only other misstatements that will affect current assets are misclassifications within balance sheet accounts, such as misclassifying a long-term asset as a current one. So, in addition to the primary preliminary judgment of materiality of $100,000, the auditor will also need to plan the audit with the $250,000 preliminary judgment about materiality for misclassifications of current assets. Qualitative Factors Also Affect Materiality Certain types of misstatements are likely to be more important to users than others, even if the dollar amounts are the same. For example:

• Amounts involving fraud are usually considered more important than unin - tentional errors of equal dollar amounts because fraud reflects on the honesty and reliability of the management or other personnel involved. For example, most users consider an intentional misstatement of inventory more important than clerical errors in inventory of the same dollar amount.

• Misstatements that are otherwise minor may be material if there are possible consequences arising from contractual obligations. Say that net working capital included in the financial statements is only a few hundred dollars more than the required minimum in a loan agreement. If the correct net working capital were less than the required minimum, putting the loan in default, the current and non current liability classifications would be materially affected.

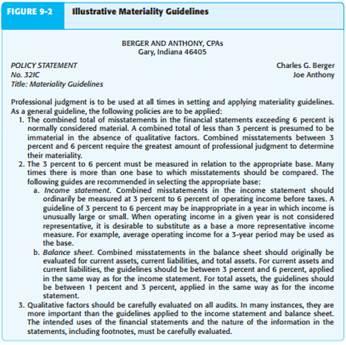

• Misstatements that are otherwise immaterial may be material if they affect a trend in earnings. For example, if reported income has increased 3 percent annually for the past 5 years but income for the current year has declined 1 percent, that change may be material. Similarly, a misstatement that would cause a loss to be reported as a profit may be of concern. Accounting and auditing standards do not provide specific materiality guidelines to practitioners. The concern is that such guidelines might be applied without considering all the complexities that should affect the auditor’s final decision. However, in this chapter, we do provide guidelines to illustrate the application of materiality. These are intended only to help you better understand the concept of applying materiality in practice. The guidelines are stated in Figure 9-2 in the form of policy guidelines of a

CPA firm. Notice that the guidelines are formulas using one or more bases and a range of percentages. The application of guidelines, such as the ones we present here, requires considerable professional judgment. Using the illustrative guidelines in Figure 9-2 (p. 253), let’s examine a preliminary judgment about materiality for Hillsburg Hardware Co. The guidelines are as follows:

If the auditor for Hillsburg Hardware decides that the general guidelines are reasonable, the first step is to evaluate whether any qualitative factors significantly affect the materiality judgment. Assuming no qualitative factors exist, if the auditor concludes at the end of the audit that combined misstatements of operating income before taxes are less than $221,000, the statements will be considered fairly stated. If the combined misstatements exceed $442,000, the statements will not be considered fairly stated. If the misstatements are between $221,000 and $442,000, a more careful consideration of all facts will be required. The auditor then applies the same process to the other three bases.

(Objective 9-3)

ALLOCATE PRELIMINARY JUDGMENT ABOUT MATERIALITY TO SEGMENTS (TOLERABLE MISSTATEMENT)

The allocation of the preliminary judgment about materiality to segments (step 2 in Figure 9-1 on page 251) is necessary because auditors accumulate evidence by segments rather than for the financial statements as a whole. If auditors have a preliminary judgment about materiality for each segment, it helps them decide the appropriate audit evidence to accumulate. For an accounts receivable balance of $1,000,000, for example, the auditor should accumulate more evidence if a misstatement of $50,000 is considered material than if $300,000 were considered material. Most practitioners allocate materiality to balance sheet rather than income state - ment accounts, because most income statement misstatements have an equal effect on the balance sheet due to the nature of double-entry accounting. For example, a $20,000 overstatement of accounts receivable is also a $20,000 overstatement of sales. It is inappropriate to allocate the preliminary judgment to both income statement and balance sheet accounts because doing so will result in double counting, which will in turn lead to smaller tolerable misstatements than is desirable. This enables auditors to allocate materiality to either income statement or balance sheet accounts. Because there are fewer balance sheet than income statement accounts in most audits, and because most audit procedures focus on balance sheet accounts, materiality should be allocated only to balance sheet accounts. When auditors allocate the preliminary judgment about materiality to account balances, the materiality allocated to any given account balance is referred to as tolerable misstatement. For example, if an auditor decides to allocate $100,000 of a total preliminary judgment about materiality of $200,000 to accounts receivable, tolerable misstatement for accounts receivable is $100,000. This means that the auditor is willing to consider accounts receivable fairly stated if it is misstated by $100,000 or less. Auditors face three major difficulties in allocating materiality to balance sheet accounts:

1. Auditors expect certain accounts to have more misstatements than others.

2. Both overstatements and understatements must be considered.

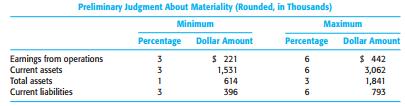

3. Relative audit costs affect the allocation. All three of these difficulties are considered in the allocation in Figure 9-3. It is worth keeping in mind that at the end of the audit, the auditor must combine all actual and estimated misstatements and compare them to the preliminary judgment about materiality. In allocating tolerable misstatement, the auditor is attempting to do the audit as efficiently as possible. Figure 9-3 illustrates the allocation approach followed by the senior, Fran Moore, for the audit of Hillsburg Hardware Co. It summarizes the balance sheet, combining certain accounts, and shows the allocation of total materiality of $442,000 (6 percent of earnings from operations). Moore’s allocation approach uses judgment in the alloca - tion, subject to the following two arbitrary requirements established by Berger and Anthony, CPAs:

• Tolerable misstatement for any account cannot exceed 60 percent of the prelimi - nary judgment (60 percent of $442,000 = $265,000, rounded).

• The sum of all tolerable misstatements cannot exceed twice the preliminary judg ment about materiality (2 × $442,000 = $884,000).

The first requirement keeps the auditor from allocating all of total materiality to one account. If, for example, all of the preliminary judgment of $442,000 is allocated to trade accounts receivable, a $442,000 misstatement in that account will be acceptable. However, it may not be acceptable to have such a large misstatement in one account, and even if it is acceptable, it does not allow for any misstatements in other accounts. There are two reasons for the second requirement, permitting the sum of the tolerable misstatement to exceed overall materiality: • It is unlikely that all accounts will be misstated by the full amount of tolerable misstatement. If, for example, other current assets have a tolerable misstatement of $100,000 but no misstatements are found in auditing those accounts, it means that the auditor, after the fact, could have allocated zero or a small tolerable misstate ment to other current assets. It is common for auditors to find fewer misstatements than tolerable misstatement. • Some accounts are likely to be overstated, whereas others are likely to be under - stated, resulting in a net amount that is likely to be less than the preliminary judgment. Notice in the allocation that the auditor is concerned about the combined effect on operating income of the misstatement of each balance sheet account. An overstatement of an asset account will therefore have the same effect on the income statement as an understatement of a liability account. In contrast, a misclassification in the balance sheet, such as a classification of a note payable as an account payable, will have no effect on operating income. Therefore, the materiality of items not affecting the income statement must be considered separately. Figure 9-3 (p. 255) also includes the rationale that Moore followed in deciding tolerable misstatement for each account. For example, she concluded that it was unnecessary to assign any tolerable misstatement to notes payable, even though it is as large as inventories. If she had assigned $132,500 to each of those two accounts, more evidence would have been required in inventories, but the confirmation of the balance in notes payable would still have been necessary. It was therefore more efficient to allocate $265,000 to inventories and none to notes payable. Similarly, she allocated $60,000 to other current assets and accrued payroll and payroll tax, both of which are large compared with the recorded account balance. Moore did so because she believes that these accounts can be verified within $60,000 by using only analytical procedures, which are low cost. If tolerable misstatement were set lower, she would have to use more costly audit procedures such as documentation and confirmation. In practice, it is often difficult to predict in advance which accounts are most likely to be misstated and whether misstatements are likely to be overstatements or under - statements. Similarly, the relative costs of auditing different account balances often cannot be determined. It is therefore a difficult professional judgment to allocate the preliminary judgment about materiality to accounts. Accordingly, many account ing firms have developed rigorous guidelines and sophisticated methods for doing so. These guidelines also help ensure the auditor appropriately documents the tolerable misstatement amounts and the related basis used to determine those amounts in the audit files. To summarize, the purpose of allocating the preliminary judgment about materiality to balance sheet accounts is to help the auditor decide the appropriate evidence to accumulate for each account on both the balance sheet and income statement. An aim of the allocation is to minimize audit costs without sacrificing audit quality. Regardless of how the allocation is done, when the audit is completed, the auditor must be confident that the combined misstatements in all accounts are less than or equal to the preliminary (or revised) judgment about materiality.

(Objective 9-4)

ESTIMATE MISSTATEMENT AND COMPARE WITH PRELIMINARY JUDGMENT

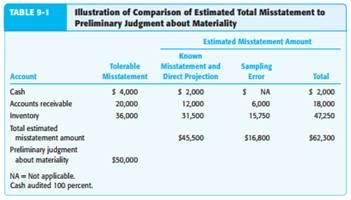

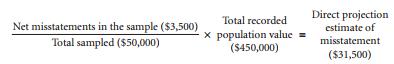

The first two steps in applying materiality involve planning (see Figure 9-1 on page 251) and are our primary concern in this chapter. The last three steps result from performing audit tests. These steps are introduced here and discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters. When auditors perform audit procedures for each segment of the audit, they docu - ment all misstatements found. Misstatements in an account can be of two types: known misstatements and likely misstatements. Known misstatements are those where the auditor can determine the amount of the misstatement in the account. For example, when auditing property, plant, and equipment, the auditor may identify capitalized leased equipment that should be expensed because it is an operating lease. There are two types of likely misstatements. The first are misstate ments that arise from differences between management’s and the auditor’s judgment about estimates of account balances. Examples are differences in the estimate for the allowance for uncol - lectible accounts or for warranty liabilities. The second are projec tions of misstatements based on the auditor’s tests of a sample from a population. For example, assume the auditor finds six client misstatements in a sample of 200 in testing inventory costs. The auditor uses these misstatements to estimate the total likely misstatements in inventory (step 3). The total is called an estimate or a “projection” or “extrapolation” because only a sample, rather than the entire population, was audited. The projected mis statement amounts for each account are combined on the worksheet (step 4), and then the combined likely misstatement is compared with materiality (step 5). Table 9-1 illustrates the last three steps in applying materiality. For simplicity, only three accounts are included. The misstatement in cash of $2,000 is a known misstate - ment related to unrecorded bank service charges detected by the auditor. Unlike for cash, the misstatements for accounts receivable and inventory are based on samples. The auditor calculates likely misstatements for accounts receivable and inventory using known misstatements detected in those samples. To illustrate the calculation, assume that in auditing inventory the auditor found $3,500 of net overstatement amounts in a sample of $50,000 of the total population of $450,000. The $3,500 identified misstatement is a known misstatement. To calculate the estimate of the likely misstatements for the total population of $450,000, the auditor makes a direct

projection of the known misstatement from the sample to the population and adds an estimate for sampling error. The calculation of the direct projection estimate of misstatement is:

(Note that the direct projection of likely misstatement for accounts receivable of $12,000 is not illustrated.) The estimate for sampling error results because the auditor has sampled only a portion of the population and there is a risk that the sample does not accurately represent the population. (We’ll discuss this in more detail in chapters 15 and 17). In this simplified example, we’ll assume the estimate for sampling error is 50 percent of the direct projection of the misstatement amounts for the accounts where sampling was used (accounts receivable and inventory). There is no sampling error for cash because the total amount of misstatement is known, not estimated. In combining the misstatements in Table 9-1 (p. 257), we can observe that the known mis statements and direct projection of likely misstatements for the three accounts adds to $45,500. However, the total sampling error is less than the sum of the individual sampling errors. This is because sampling error represents the maximum misstate ment in account details not audited. It is unlikely that this maximum misstatement amount exists in all accounts subjected to sampling. Table 9-1 shows that total estimated likely misstatement of $62,300 exceeds the preliminary judgment about materiality of $50,000. The major area of difficulty is inventory, where estimated misstatement of $47,250 is significantly greater than tolerable misstatement of $36,000. Because the estimated combined misstatement exceeds the preliminary judgment, the financial statements are not acceptable. The auditor can either determine whether the estimated likely misstatement actually exceeds $50,000 by performing additional audit procedures or require the client to make an adjustment for estimated misstatements. If the auditor decides to perform additional audit procedures, they will be concentrated in the inventory area. If the estimated net overstatement amount for inventory had been $28,000 ($18,000 plus $10,000 sampling error), the auditor probably would not have needed to expand audit tests because it would have met both the tests of tolerable misstatement ($36,000) and the preliminary judgment about materiality ($2,000 + $18,000 + $28,000 = $48,000 < $50,000).="" in="" fact,="" the="" auditor="" would="" have="" had="" some="" leeway="" with="" that="" amount="" because="" the="" results="" of="" cash="" and="" accounts="" receivable="" procedures="" indicate="" that="" those="" accounts="" are="" within="" their="" tolerable="" misstatement="" limits.="" if="" the="" auditor="" approaches="" the="" audit="" of="" the="" accounts="" in="" a="" sequential="" manner,="" the="" findings="" of="" the="" audit="" of="" accounts="" audited="" earlier="" can="" be="" used="" to="" revise="" the="" tolerable="" misstatement="" established="" for="" accounts="" audited="" later.="" in="" the="" illustration,="" if="" the="" auditor="" had="" audited="" cash="" and="" accounts="" receivable="" before="" inventories,="" tolerable="" misstatement="" for="" inventories="" could="" have="" been="">

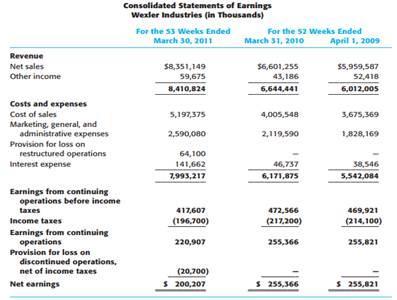

Consolidated Statements of Earnings Wexler Industries (in Thousands) For the 52 Weeks Ended March 31, 2010 For the S3 Weeks Ended March 30, 2011 April 1, 2009 Revenue $8,351,149 59,675 $6,601,255 43, 186 Net sales S5,959,587 Other income 52,418 8,410,824 6,644,441 6,012,005 Costs and expenses Cost of sales 5,197,375 4,005,548 3,675,369 Marketing, general, and administrative expenses 2,590,080 2,119,590 1828,169 Provision for loss on restructured operations Interest expense 64,100 141,662 7,993,217 46,737 6,171,875 38,546 5,542,084 Earnings from continuing operations before income taxes 417,607 472,566 469,921 Income taxes Earnings from continuing operations Provision for loss on discontinued operations, (196.700) (217.200) (214,100) 220,907 255,366 255,821 net of income taxes (20,700) $ 200,207 Net earnings S 255,366 S 255,821

Step by Step Solution

3.33 Rating (156 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started