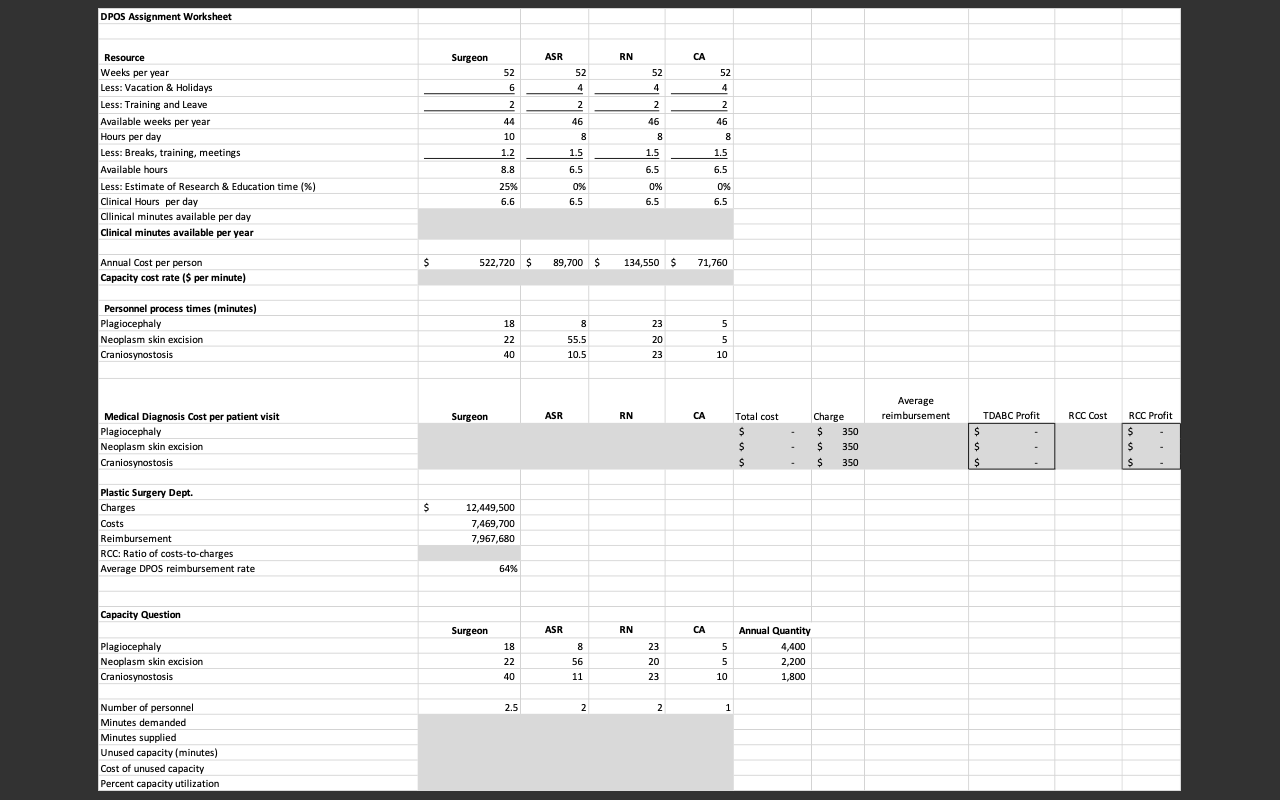

Use the accompanying Excel spreadsheet to calculate the costs and profit margins of the three different office visits using i) the RCC method and ii) TDABC (Time-Driven Activity Based Costing) method. Report the costs and profits in a small table. What explains the difference in costs and profits using the two methods. What decisions would the department heads make differently based on the more accurate cost estimates?

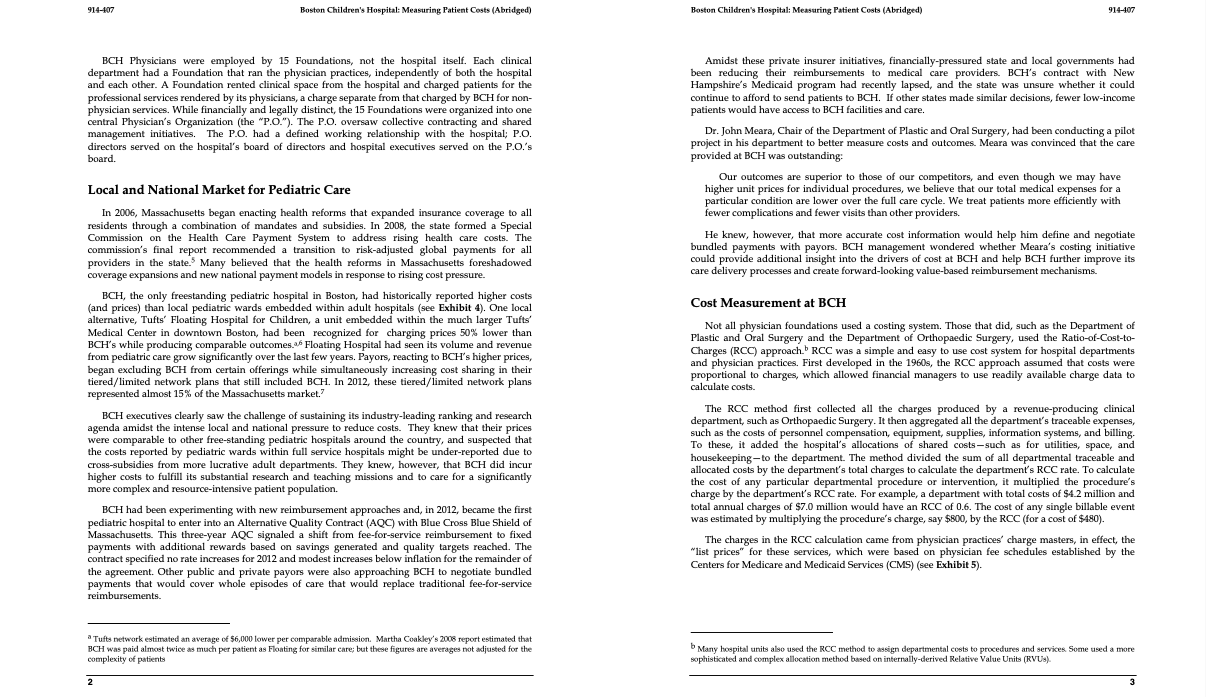

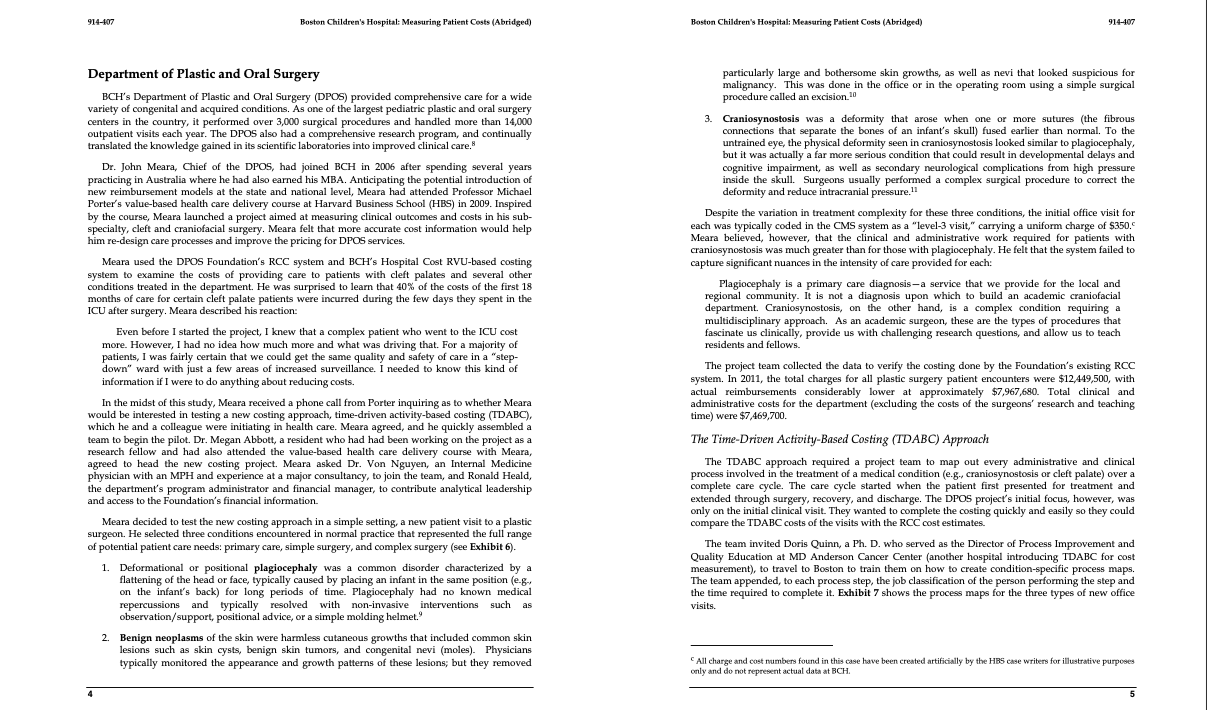

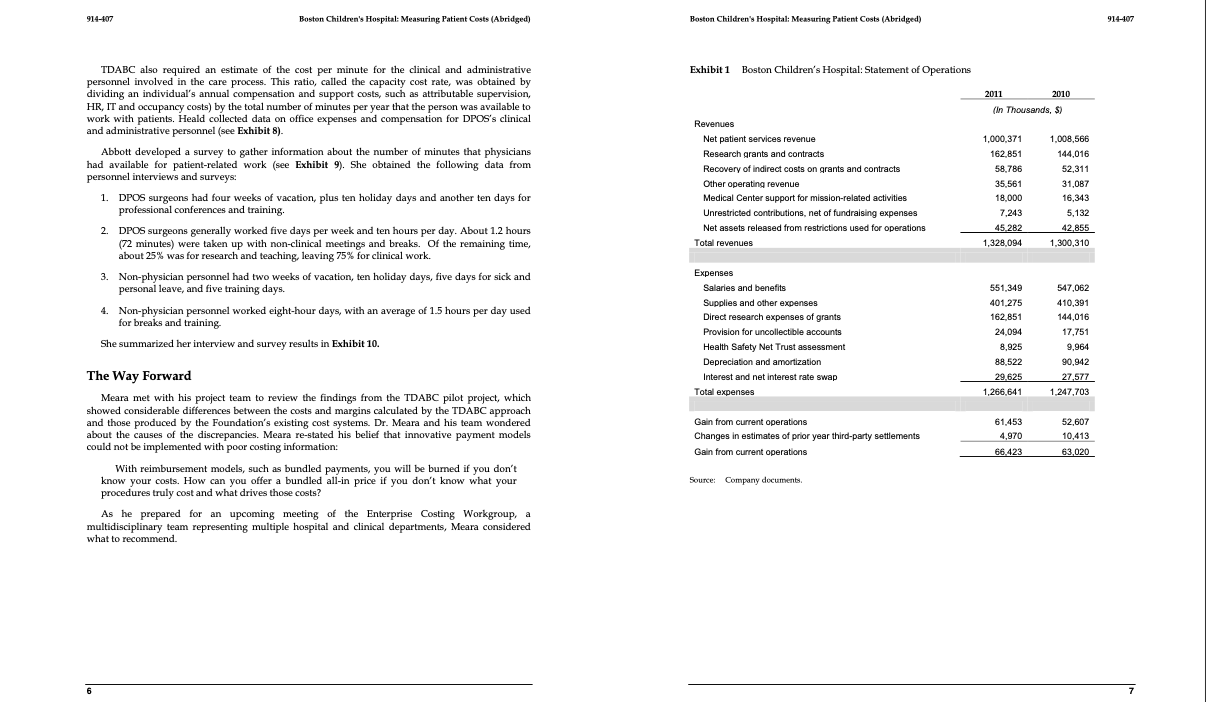

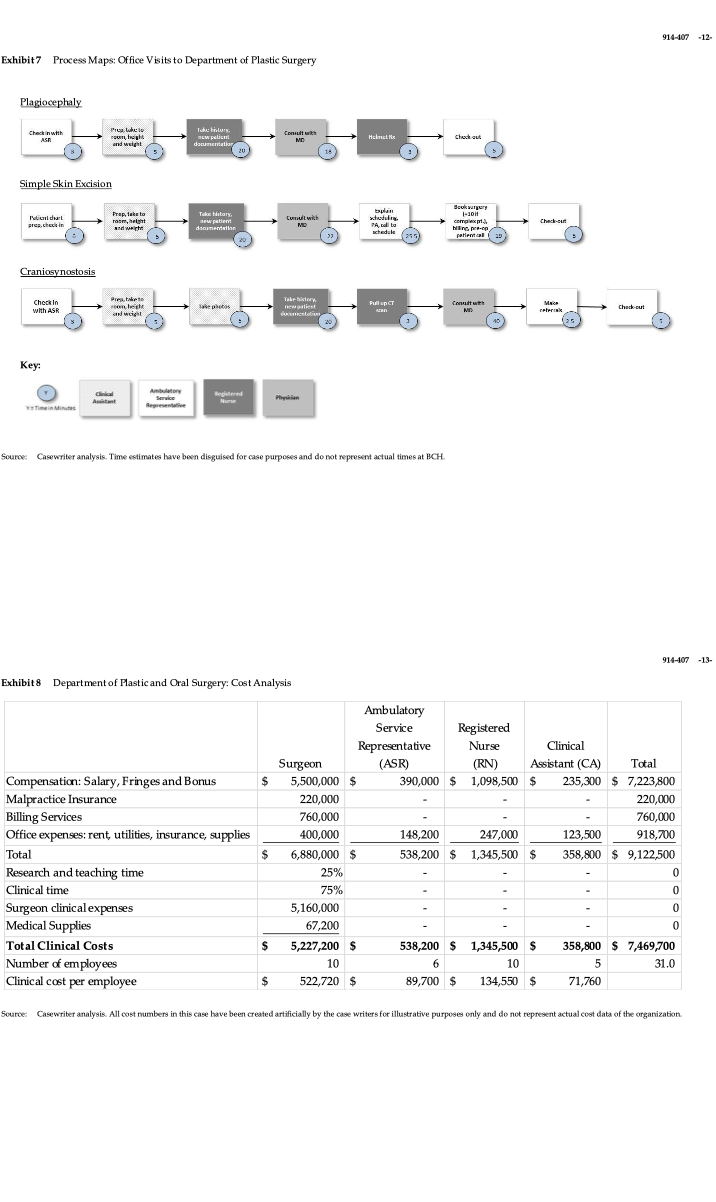

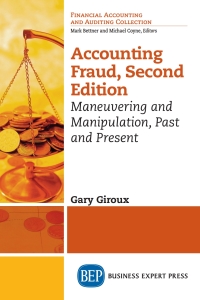

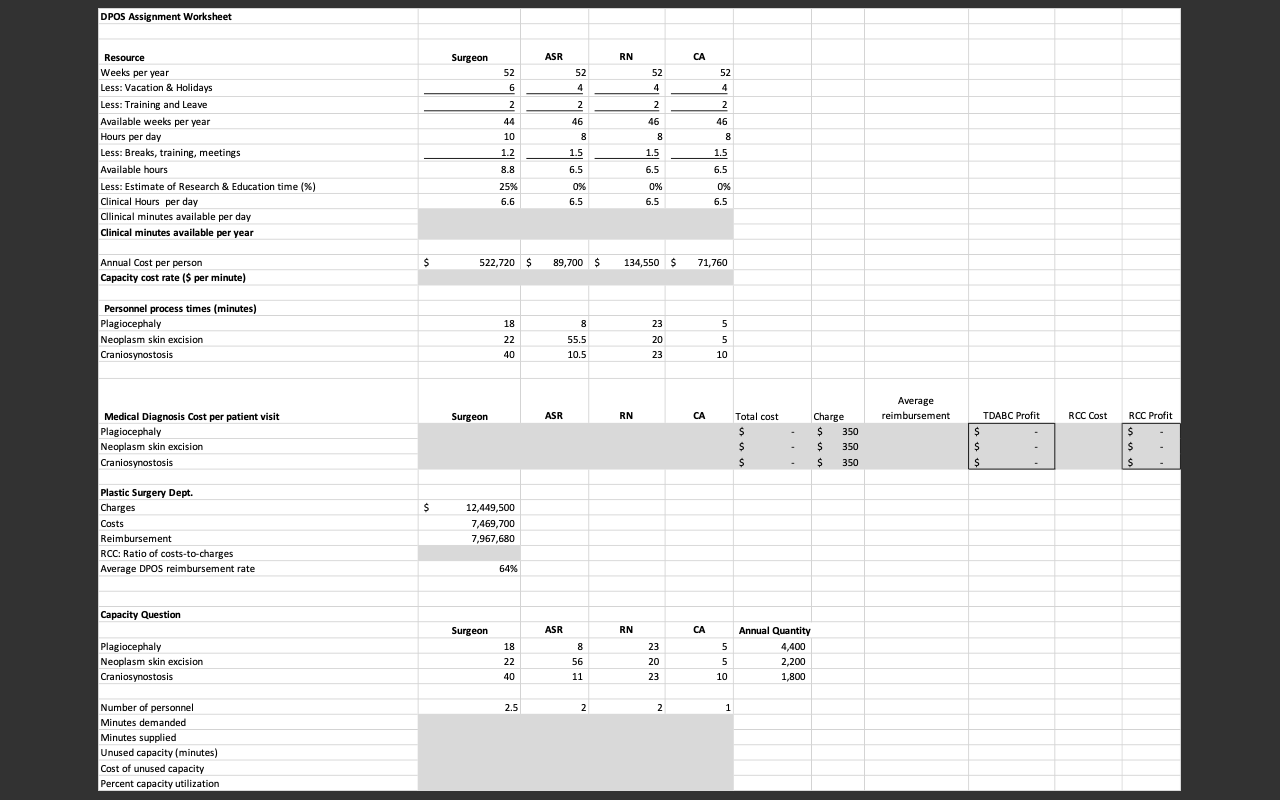

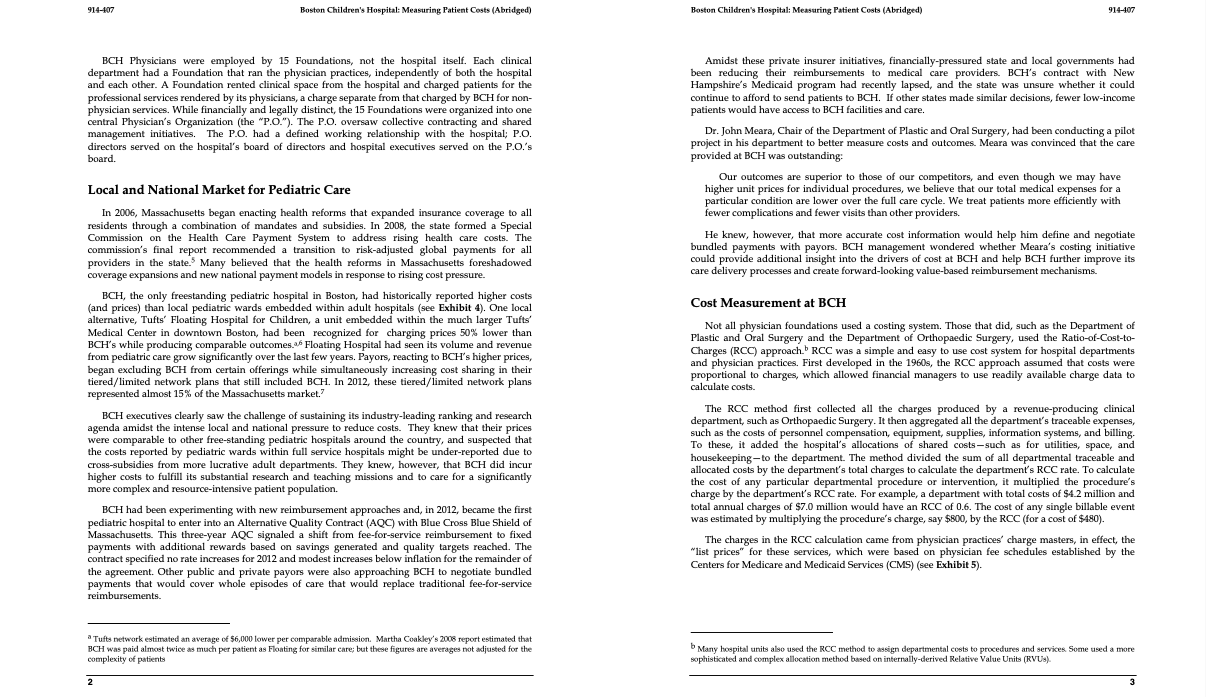

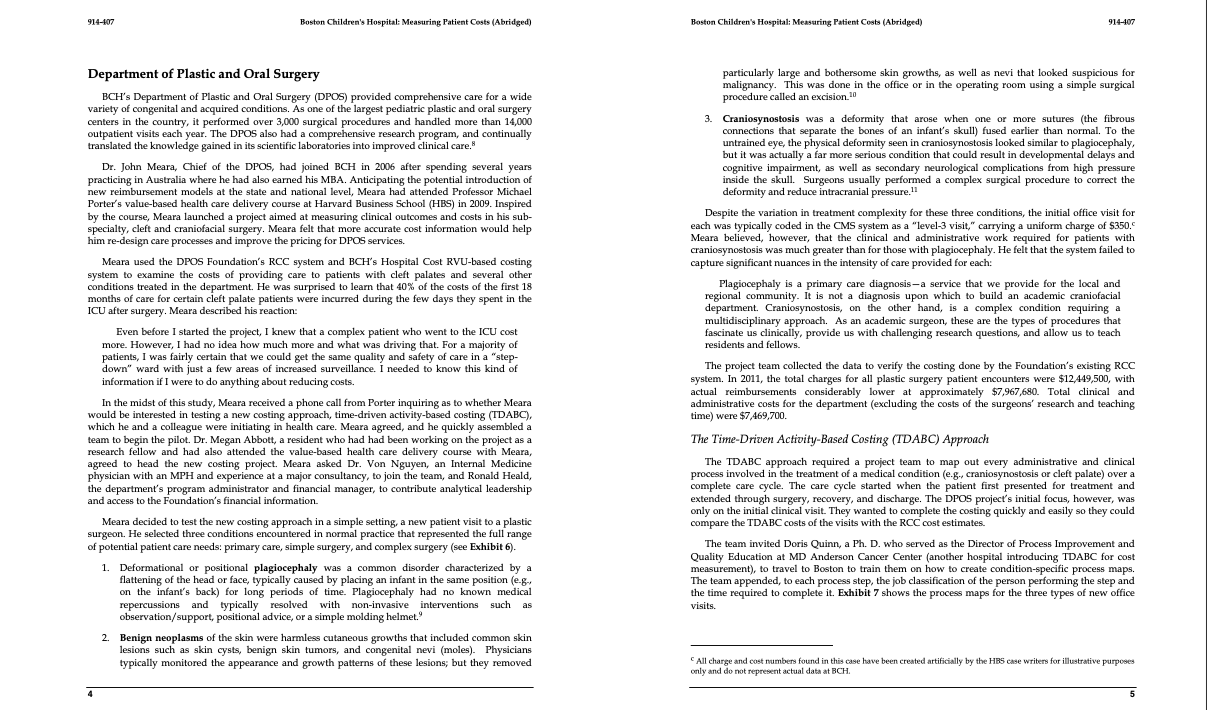

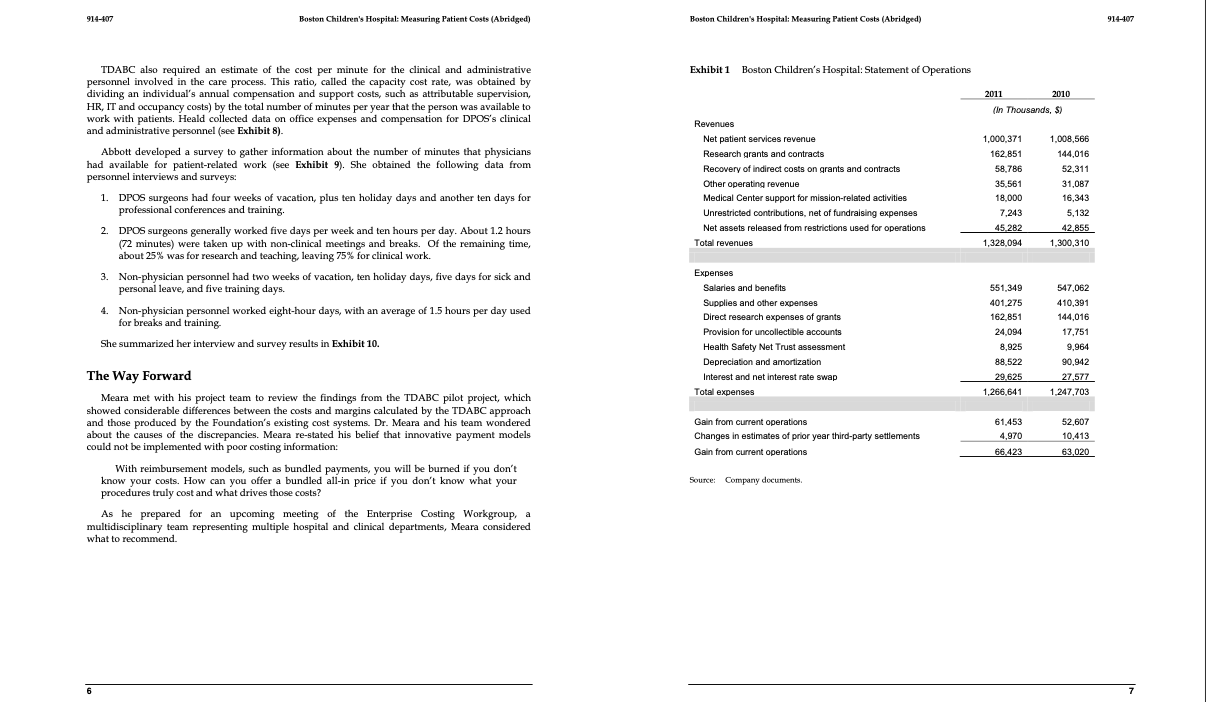

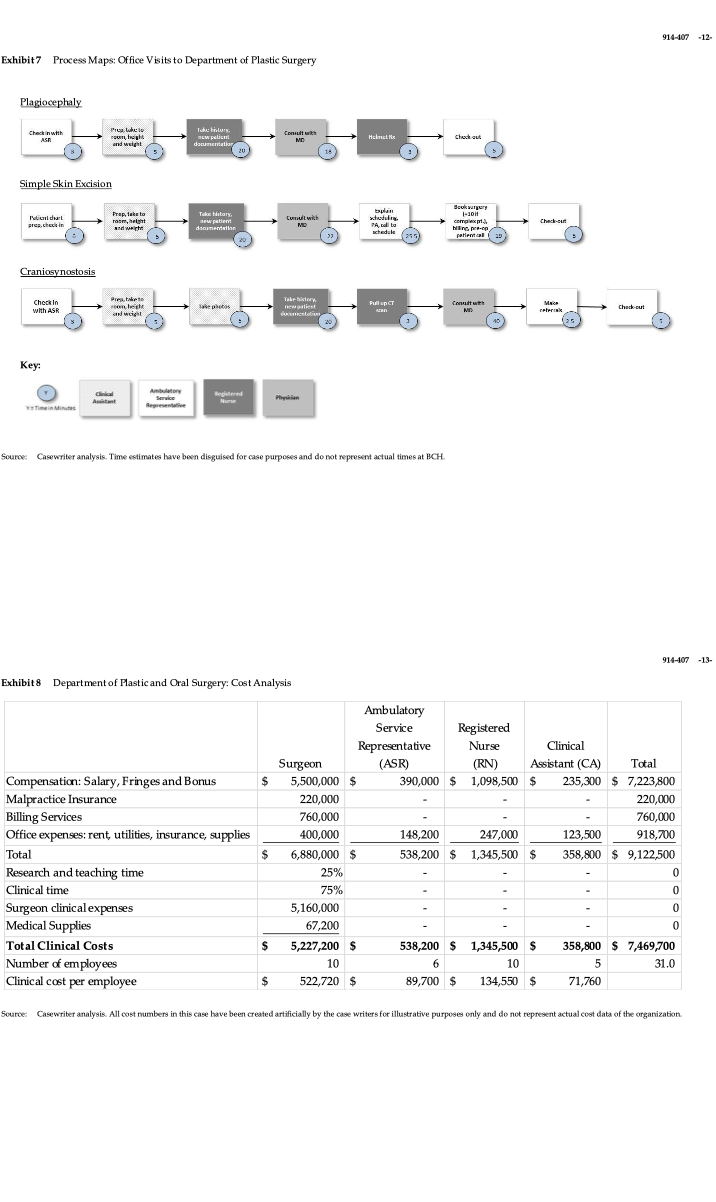

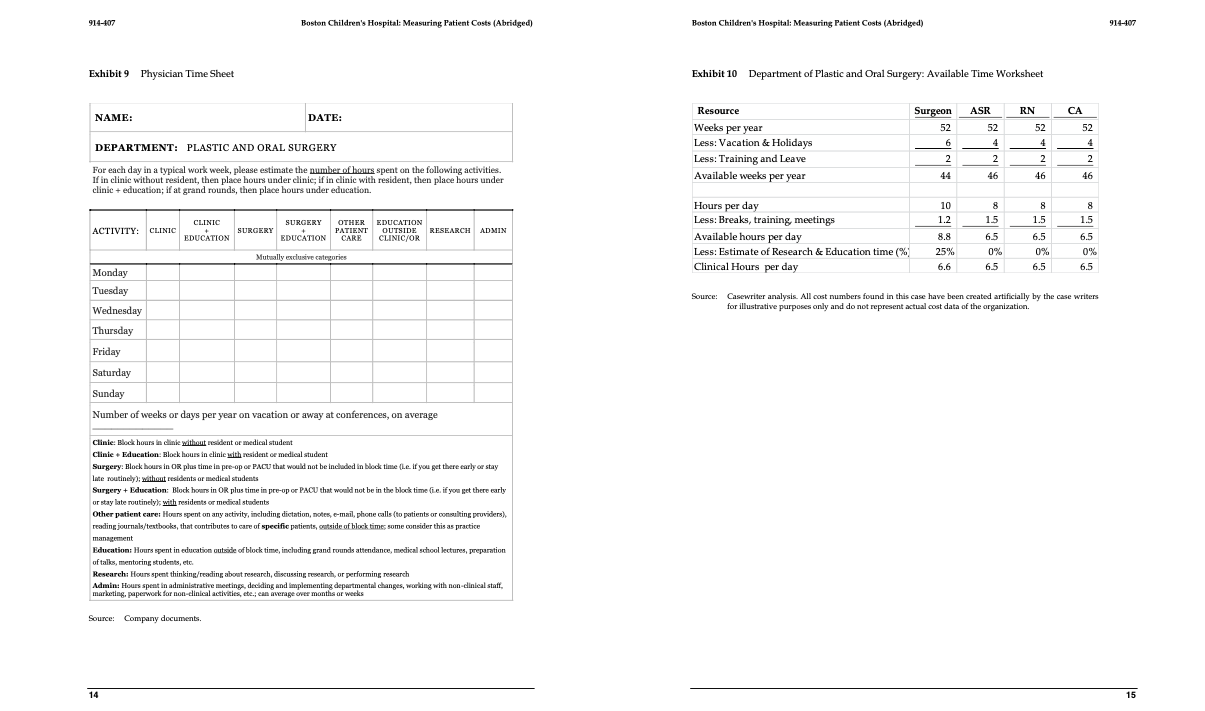

DPOS Assignment Worksheet Surgeon ASR RN CA 52 6 52 4 52 4 2 Resource Weeks per year Less: Vacation & Holidays Less: Training and Leave Available weeks per year Hours per day Less: Breaks, training, meetings silahla bure Less: Estimate of Research & Education time (%) Clinical Hours per day Cllinical minutes available per day Clinical minutes available per year 2 44 MA 10 1.2 46 8 1.5 6.5 52 4 2 46 8 8 1.5 6.5 2 2 46 8 1.5 8.8 6.5 25% 6.6 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 $ 522,720 $ 89,700 $ 134,550 $ 71,760 Annual Cost per person Capacity cost rate ($ per minute) 18 8 5 Personnel process times (minutes) Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis 23 20 55.5 5 22 40 10.5 23 10 Average reimbursement Surgeon ASR RN CA RCC Cost Medical Diagnosis Cost per patient visit Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis Total cost $ $ $ Charge $ 350 $ 350 $ 350 TDABC Profit $ $ $ RCC Profit $ $ $ - $ Plastic Surgery Dept. Charges Costs Reimbursement RCC: Ratio of costs-to-charges : - Average DPOS reimbursement rate 12,449,500 7,469,700 7,967,680 64% Capacity Question Surgeon ASR RN CA 23 Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis 18 22 40 8 56 11 Annual Quantity 4,400 2,200 1,800 5 5 10 20 23 2.5 2 2 1 1 Number of personnel Minutes demanded Minutes supplied Unused capacity (minutes) Cost of unused capacity Percent capacity utilization 914--07 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 BCH Physicians were employed by 15 Foundations, not the hospital itself. Each clinical department had a Foundation that ran the physician practices, independently of both the hospital and each other. A Foundation rented clinical space from the hospital and charged patients for the professional services rendered by its physicians, a charge separate from that charged by BCH for non- physician services. While financially and legally distinct , the 15 Foundations were organized into one central Physician's Organization (the "P.O."). The P.O. oversaw collective contracting and shared management initiatives. The P.O. had a defined working relationship with the hospital; P.O. directors served on the hospital's board of directors and hospital executives served on the P.O.'s board. Amidst these private insurer initiatives, financially-pressured state and local governments had been reducing their reimbursements to medical care providers. BCH's contract with New Hampshire's Medicaid program had recently lapsed, and the state was unsure whether it could continue to afford to send patients to BCH. If other states made similar decisions, fewer low-income patients would have access to BCH facilities and care, Dr. John Meara, Chair of the Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery, had been conducting a pilot project in his department to better measure costs and outcomes. Meara was convinced that the care provided at BCH was outstanding: Our outcomes are superior to those of our competitors, and even though we may have higher unit prices for individual procedures, we believe that our total medical expenses for a particular condition are lower over the full care cycle. We treat patients more efficiently with fewer complications and fewer visits than other providers. He knew, however, that more accurate cost information would help him define and negotiate bundled payments with payors. BCH management wondered whether Meara's costing initiative could provide additional insight into the drivers of cost at BCH and help BCH further improve its care delivery processes and create forward-looking value-based reimbursement mechanisms. Cost Measurement at BCH Not all physician foundations used a costing system. Those that did, such as the Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, used the Ratio-of-Cost-to- Charges (RCC) approach. RCC was a simple and easy to use cost system for hospital departments and physician practices. First developed in the 1960s, the RCC approach assumed that costs were proportional to charges, which allowed financial managers to use readily available charge data to calculate costs. Local and National Market for Pediatric Care In 2006, Massachusetts began enacting health reforms that expanded insurance coverage to all residents through a combination of mandates and subsidies. In 2008, the state formed a Special Commission on the Health Care Payment System to address rising health care costs. The commission's final report recommended a transition to risk-adjusted global payments for all providers in the state. Many believed that the health reforms in Massachusetts foreshadowed coverage expansions and new national payment models in response to rising cost pressure. BCH, the only freestanding pediatric hospital in Boston, had historically reported higher costs (and prices) than local pediatric wards embedded within adult hospitals (see Exhibit 4). One local alternative, Tufts Floating Hospital for Children, a unit embedded within the much larger Tufts' Medical Center in downtown Boston, had been recognized for charging prices 50% lower than BCH's while producing comparable outcomes.3.6 Floating Hospital had seen its volume and revenue from pediatric care grow significantly over the last few years. Payors, reacting to BCH's higher prices, began excluding BCH from certain offerings while simultaneously increasing cost sharing in their tiered/limited network plans that still included BCH. In 2012, these tiered/limited network plans represented almost 15% of the Massachusetts market.' BCH executives clearly saw the challenge of sustaining its industry-leading ranking and research agenda amidst the intense local and national pressure to reduce costs. They knew that their prices were comparable to other free-standing pediatric hospitals around the country, and suspected that the costs reported by pediatric wards within full service hospitals might be under-reported due to cross-subsidies from more lucrative adult departments. They knew, however, that BCH did incur higher costs fulfill its substantial research and teaching missions and to care for a significantly more complex and resource-intensive patient population. BCH had been experimenting with new reimbursement approaches and, in 2012, became the first pediatric hospital to enter into an Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts. This three-year AQC signaled a shift from fee-for-service reimbursement to fixed payments with additional rewards based on savings generated and quality targets reached. The contract specified no rate increases for 2012 and modest increases below inflation for the remainder of the agreement. Other public and private payors were also approaching BCH to negotiate bundled payments that would cover whole episodes of care that would replace traditional fee-for-service reimbursements. The RCC method first collected all the charges produced by a revenue-producing clinical department, such as Orthopaedic Surgery. It then aggregated all the department's traceable expenses, such as the costs of personnel compensation, equipment , supplies, information systems, and billing. To these, it added the hospital's allocations of shared costs-such as for utilities, space, and housekeeping-to the department. The method divided the sum of all departmental traceable and allocated costs by the department's total charges to calculate the department's RCC rate. To calculate the cost of any particular departmental procedure or intervention, it multiplied the procedure's charge by the department's RCC rate. For example, a department with total costs of $4.2 million and total annual charges of $7.0 million would have an RCC of 0.6. The cost of any single billable event was estimated by multiplying the procedure's charge, say $800, by the RCC (for a cost of $480). The charges in the RCC calculation came from physician practices' charge masters, in effect, the "list prices" for these services, which were based on physician fee schedules established by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (see Exhibit 5). Tufts network estimated an average of $6,000 lower per comparable admission. Martha Coakley's 2008 report estimated that BCH was paid almost twice as much per patient as Floating for similar care; but these figures are averages not adjusted for the complexity of patients Many hospital units also used the RCC method to assign departmental costs to procedures and services. Some used a more sophisticated and complex allocation method based on internally-derived Relative Value Units (RVU). 3 914-407 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery BCH's Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery (DPOS) provided comprehensive care for a wide variety of congenital and acquired conditions. As one of the largest pediatric plastic and oral surgery centers in the country, it performed over 3,000 surgical procedures and handled more than 14,000 outpatient visits each year. The DPOS also had a comprehensive research program, and continually translated the knowledge gained in its scientific laboratories into improved clinical care. Dr. John Meara, Chief of the DPOS, had joined BCH in 2006 after spending several years practicing in Australia where he had also earned his MBA. Anticipating the potential introduction of new reimbursement models at the state and national level, Meara had attended Professor Michael Porter's value-based health care delivery course at Harvard Business School (HBS) in 2009. Inspired by the course, Meara launched a project aimed at measuring clinical outcomes and costs in his sub- specialty, cleft and craniofacial surgery. Meara felt that more accurate cost information would help him re-design care processes and improve the pricing for DPOS services. Meara used the DPOS Foundation's RCC system and BCH's Hospital Cost RVU-based costing system to examine the costs of providing care to patients with cleft palates and several other conditions treated in the department. He was surprised to learn that 40% of the costs of the first 18 months of care for certain cleft palate patients were incurred during the few days they spent in the ICU after surgery. Meara described his reaction: Even before I started the project, I knew that a complex patient who went to the ICU cost more. However, I had no idea how much more and what was driving that. For a majority of patients, I was fairly certain that we could get the same quality and safety of care in a "step- down" ward with just a few areas of increased surveillance. I needed to know this kind of information if I were to do anything about reducing costs. In the midst of this study, Meara received a phone call from Porter inquiring as to whether Meara would be interested in testing a new costing approach, time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC), which he and a colleague were initiating in health care. Meara agreed, and he quickly assembled a team to begin the pilot. Dr. Megan Abbott, a resident who had had been working on the project as a research fellow and had also attended the value-based health care delivery course with Meara, agreed to head the new costing project. Meara asked Dr. Von Nguyen, an Internal Medicine physician with an MPH and experience at a major consultancy, to join the team, and Ronald Heald, the department's program administrator and financial manager, to contribute analytical leadership and access to the Foundation's financial information. Meara decided to test the new costing approach in a simple setting, a new patient visit to a plastic surgeon. He selected three conditions encountered in normal practice that represented the full range of potential patient care needs: primary care, simple surgery, and complex surgery (see Exhibit 6). 1. Deformational or positional plagiocephaly was a common disorder characterized by a flattening of the head or face, typically caused by placing an infant in the same position (e.g. on the infant's back) for long periods of time. Plagiocephaly had no known medical repercussions and typically resolved with non-invasive interventions such observation/support, positional advice, or a simple molding helmet. 2. Benign neoplasms of the skin were harmless cutaneous growths that included common skin lesions such as skin cysts, benign skin tumors, and congenital nevi (moles). Physicians typically monitored the appearance and growth patterns of these lesions, but they removed particularly large and bothersome skin growths, as well as nevi that looked suspicious for malignancy. This was done in the office or in the operating room using a simple surgical procedure called an excision 10 3. Craniosynostosis was a deformity that arose when one or more sutures (the fibrous connections that separate the bones of an infant's skull) fused earlier than normal. To the untrained eye, the physical deformity seen in craniosynostosis looked similar to plagiocephaly, but it was actually a far more serious condition that could result in developmental delays and cognitive impairment, as well as secondary neurological complications from high pressure inside the skull. Surgeons usually performed a complex surgical procedure to correct the deformity and reduce intracranial pressure. Despite the variation in treatment complexity for these three conditions, the initial office visit for each was typically coded in the CMS system as a "level-3 visit," carrying a uniform charge of $350. Meara believed, however, that the clinical and administrative work required for patients with craniosynostosis was much greater than for those with plagiocephaly. He felt that the system failed to capture significant nuances in the intensity of care provided for each: Plagiocephaly is a primary care diagnosis-a service that we provide for the local and regional community. It is not a diagnosis upon which to build an academic craniofacial department. Craniosynostosis, on the other hand, is a complex condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach. As an academic surgeon, these are the types of procedures that fascinate us clinically, provide us with challenging research questions, and allow us to teach residents and fellows. The project team collected the data to verify the costing done by the Foundation's existing RCC system. In 2011, the total charges for all plastic surgery patient encounters were $12,449,500, with actual reimbursements considerably lower at approximately $7,967,680 Total clinical and administrative costs for the department (excluding the costs of the surgeons' research and teaching time) were $7,469,700. The Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) Approach The TDABC approach uired a project team to map out every administrative and clinical process involved in the treatment of a medical condition (e.g. craniosynostosis or cleft palate) over a complete care cycle. The care cycle started when the patient first presented for treatment and extended through surgery, recovery, and discharge. The DPOS project's initial focus, however, was only on the initial clinical visit. They wanted to complete the costing quickly and easily so they could compare the TDABC costs of the visits with the RCC cost estimates. The team invited Doris Quinn, a Ph. D. who served as the Director of Process Improvement and Quality Education at MD Anderson Cancer Center (another hospital introducing TDABC for cost measurement), to travel to Boston to train them on how to create condition-specific process maps. The team appended, to each process step, the job classification of the person performing the step and the time required to complete it. Exhibit 7 shows the process maps for the three types of new office visits. as All charge and cost numbers found in this case have been created artificially by the HBS case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual data at BCH 914-107 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 Exhibit 1 Boston Children's Hospital Statement of Operations 2011 2010 (In Thousands, S) TDABC also required an estimate of the cost per minute for the clinical and administrative personnel involved in the care process. This ratio, called the capacity cost rate, was obtained by dividing an individual's annual compensation and support costs, such as attributable supervision, HR, IT and occupancy costs) by the total number of minutes per year that the person was available to work with patients. Heald collected data on office expenses and compensation for DPOS's clinical and administrative personnel (see Exhibit 8). Abbott developed a survey to gather information about the number of minutes that physicians had available for patient-related work (see Exhibit 9). She obtained the following data from personnel interviews and surveys: DPOS surgeons had four weeks of vacation, plus ten holiday days and another ten days for professional conferences and training. 2. DPOS surgeons generally worked five days per week and ten hours per day. About 1.2 hours (72 minutes) were taken up with non-clinical meetings and breaks. Of the remaining time, about 25% was for research and teaching, leaving 75% for clinical work. 3. Non-physician personnel had two weeks of vacation, ten holiday days, five days for sick and personal leave, and five training days. 4. Non-physician personnel worked eight-hour days, with an average of 1.5 hours per day used for breaks and training She summarized her interview and survey results in Exhibit 10. Revenues Net patient services revenue Research grants and contracts Recovery of indirect costs on grants and contracts Other operating revenue Medical Center support for mission-related activities Unrestricted contributions, net of fundraising expenses Net assets released from restrictions used for operations Total revenues 1,000,371 162.851 58.786 35,561 18.000 7,243 45.282 1,328,094 1.008,566 144,016 52,311 31,087 16,343 5,132 42.855 1,300,310 1. 551,349 401 275 162.851 Expenses Salaries and benefits Supplies and other expenses Direct research expenses of grants Provision for uncollectible accounts Health Safety Net Trust assessment Depreciation and amortization Interest and net interest rate swap Total expenses 24,094 8,925 88,522 29.625 1,266,641 547,062 410.391 144,016 17,751 9,964 90,942 27,577 1.247,703 The Way Forward Meara met with his project team to review the findings from the TDABC pilot project, which showed considerable differences between the costs and margins calculated by the TDABC approach and those produced by the Foundation's existing cost systems. Dr. Meara and his team wondered about the causes of the discrepancies. Meara re-stated his belief that innovative payment models could not be implemented with poor costing information: With reimbursement models, such as bundled payments, you will be burned if you don't know your costs. How can you offer a bundled all-in price if you don't know what your procedures truly cost and what drives those costs? As he prepared for an upcoming meeting of the Enterprise Costing Workgroup, a multidisciplinary team representing multiple hospital and clinical departments, Meara considered what to recommend. Gain from current operations Changes in estimates of prior year third-party settlements Gain from current operations 61.453 4,970 66.423 52,607 10,413 63,020 Source: Company documents 6 7 914-107 -12- Exhibit7 Process Maps: Office Visits to Department of Plastic Surgery Plagiocephaly Check in with ASR Peuwe PORT and weight Tube Bilary cw pelin documenter 20 Hence Check out Consult with MO (15 Simple Skin Excision local dat prechein Prap, takata rasm, hent and with Take itary document Comitwist MD bplain didel TA call to schedule 1-10 com Hling - patient Check-our 59 Craniosynostosis Take history Check in with ASR Prentar on leche and weight a photo Pull upcy Aran Conut with MD M reteria Check out Key: Clinical A Registered Phrysan Service Represente Yemen Minutes Source: Casewriter analysis. Time estimates have been disguised for case purposes and do not represent actual times at BCH 914-107-13- Exhibit 8 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery: Cost Analysis $ Ambulatory Service Registered Representative Nurse Clinical Surgeon (ASR) (RN) Assistant (CA) Total 5,500,000 $ 390,000 $1,098,500 $ 235,300 $ 7,223,800 220,000 220,000 760,000 760,000 400,000 148,200 247,000 123,500 918,700 6,880,000 $ 538,200 $ 1,345,500 $ 358,800 $ 9,122,500 25% 0 75% 0 0 5,160,000 0 67,200 0 5,227,200 $ 538,200 $ 1,345,500 $ 358,800 $ 7,469,700 10 6 10 5 31.0 522,720 $ 89,700 $ 134,550 $ 71,760 Compensation: Salary, Fringes and Bonus Malpractice Insurance Billing Services Office expenses: rent, utilities, insurance, supplies Total Research and teaching time Clinical time Surgeon clinical expenses Medical Supplies Total Clinical Costs Number of employees Clinical cost per employee $ $ $ Source: Casewriter analysis. All cost numbers in this case have been created artificially by the case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual cost data of the organization 914--07 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-107 Exhibit 9 Physician Time Sheet Exhibit 10 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery: Available Time Worksheet Resource ASR RN CA NAME: : DATE: 52 52 4 DEPARTMENT: PLASTIC AND ORAL SURGERY Surgeon 52 6 2 44 Weeks per year Less: Vacation & Holidays Less: Training and Leave Available weeks per year 4 2 2 52 4 2 2 For each day in a typical work week, please estimate the number of hours spent on the following activities. If in clinic without resident, then place hours under clinic; if in clinic with resident, then place hours under clinic + education; if at grand rounds, then place hours under education. 46 46 46 8 8 10 1.2 8 1.5 1.5 1.5 ACTIVITY: CLINIC CLINIC EDUCATION SURGERY SURGERY EDUCATION OTHER EDUCATION PATIENT OUTSIDE CARE CLINIC/OR RESEARCH ADMIN Hours per day Less: Breaks, training meetings Available hours per day Less: Estimate of Research & Education time % Clinical Hours per day 65 Mutually exclusive categories 8.8 25% 6.6 6.5 0% 6.5 6.5 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Source: Casewriter analysis. All cost numbers found in this case have been created artificially by the case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual cost data of the organization. Friday Saturday Sunday Number of weeks or days per year on vacation or away at conferences, on average Clinie: Block hours in line without resident or medical student Clinie Education: Block hours in elinie with resident of medical student Surgery: Block hours in OR plus time in pee-por PACU that would not be included in block time (Lc. if you get there early or stay late routinely): without residents or medical students Surgery + Education: Block hours in OR plus time in pre-op or PACU that would not be in the block time te. if you get there early or stay late routinely with residents or medical students Other patient care: Hours spent on any activity, including dictation, notes, e- mail, phone calls (to patients or consulting providers) reading journals/textbooks, that contributes to care of specific patients, getside of block times some consider this as practice management Education: Hours spent in education outside of block time, including grand rounds attendance, medical school lectures, preparation of talks, mentoring students, etc. Research: Hours spent thinking/reading about research, discussing research, or performing research Admin: Hours spent in administrative meetings, deciding and implementing departmental changes, working with non-clinical staff, marketing, paperwork for non-clinical activities, ete, can average over months or weeks Source: Company documents. 14 15 DPOS Assignment Worksheet Surgeon ASR RN CA 52 6 52 4 52 4 2 Resource Weeks per year Less: Vacation & Holidays Less: Training and Leave Available weeks per year Hours per day Less: Breaks, training, meetings silahla bure Less: Estimate of Research & Education time (%) Clinical Hours per day Cllinical minutes available per day Clinical minutes available per year 2 44 MA 10 1.2 46 8 1.5 6.5 52 4 2 46 8 8 1.5 6.5 2 2 46 8 1.5 8.8 6.5 25% 6.6 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 $ 522,720 $ 89,700 $ 134,550 $ 71,760 Annual Cost per person Capacity cost rate ($ per minute) 18 8 5 Personnel process times (minutes) Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis 23 20 55.5 5 22 40 10.5 23 10 Average reimbursement Surgeon ASR RN CA RCC Cost Medical Diagnosis Cost per patient visit Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis Total cost $ $ $ Charge $ 350 $ 350 $ 350 TDABC Profit $ $ $ RCC Profit $ $ $ - $ Plastic Surgery Dept. Charges Costs Reimbursement RCC: Ratio of costs-to-charges : - Average DPOS reimbursement rate 12,449,500 7,469,700 7,967,680 64% Capacity Question Surgeon ASR RN CA 23 Plagiocephaly Neoplasm skin excision Craniosynostosis 18 22 40 8 56 11 Annual Quantity 4,400 2,200 1,800 5 5 10 20 23 2.5 2 2 1 1 Number of personnel Minutes demanded Minutes supplied Unused capacity (minutes) Cost of unused capacity Percent capacity utilization 914--07 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 BCH Physicians were employed by 15 Foundations, not the hospital itself. Each clinical department had a Foundation that ran the physician practices, independently of both the hospital and each other. A Foundation rented clinical space from the hospital and charged patients for the professional services rendered by its physicians, a charge separate from that charged by BCH for non- physician services. While financially and legally distinct , the 15 Foundations were organized into one central Physician's Organization (the "P.O."). The P.O. oversaw collective contracting and shared management initiatives. The P.O. had a defined working relationship with the hospital; P.O. directors served on the hospital's board of directors and hospital executives served on the P.O.'s board. Amidst these private insurer initiatives, financially-pressured state and local governments had been reducing their reimbursements to medical care providers. BCH's contract with New Hampshire's Medicaid program had recently lapsed, and the state was unsure whether it could continue to afford to send patients to BCH. If other states made similar decisions, fewer low-income patients would have access to BCH facilities and care, Dr. John Meara, Chair of the Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery, had been conducting a pilot project in his department to better measure costs and outcomes. Meara was convinced that the care provided at BCH was outstanding: Our outcomes are superior to those of our competitors, and even though we may have higher unit prices for individual procedures, we believe that our total medical expenses for a particular condition are lower over the full care cycle. We treat patients more efficiently with fewer complications and fewer visits than other providers. He knew, however, that more accurate cost information would help him define and negotiate bundled payments with payors. BCH management wondered whether Meara's costing initiative could provide additional insight into the drivers of cost at BCH and help BCH further improve its care delivery processes and create forward-looking value-based reimbursement mechanisms. Cost Measurement at BCH Not all physician foundations used a costing system. Those that did, such as the Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery and the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, used the Ratio-of-Cost-to- Charges (RCC) approach. RCC was a simple and easy to use cost system for hospital departments and physician practices. First developed in the 1960s, the RCC approach assumed that costs were proportional to charges, which allowed financial managers to use readily available charge data to calculate costs. Local and National Market for Pediatric Care In 2006, Massachusetts began enacting health reforms that expanded insurance coverage to all residents through a combination of mandates and subsidies. In 2008, the state formed a Special Commission on the Health Care Payment System to address rising health care costs. The commission's final report recommended a transition to risk-adjusted global payments for all providers in the state. Many believed that the health reforms in Massachusetts foreshadowed coverage expansions and new national payment models in response to rising cost pressure. BCH, the only freestanding pediatric hospital in Boston, had historically reported higher costs (and prices) than local pediatric wards embedded within adult hospitals (see Exhibit 4). One local alternative, Tufts Floating Hospital for Children, a unit embedded within the much larger Tufts' Medical Center in downtown Boston, had been recognized for charging prices 50% lower than BCH's while producing comparable outcomes.3.6 Floating Hospital had seen its volume and revenue from pediatric care grow significantly over the last few years. Payors, reacting to BCH's higher prices, began excluding BCH from certain offerings while simultaneously increasing cost sharing in their tiered/limited network plans that still included BCH. In 2012, these tiered/limited network plans represented almost 15% of the Massachusetts market.' BCH executives clearly saw the challenge of sustaining its industry-leading ranking and research agenda amidst the intense local and national pressure to reduce costs. They knew that their prices were comparable to other free-standing pediatric hospitals around the country, and suspected that the costs reported by pediatric wards within full service hospitals might be under-reported due to cross-subsidies from more lucrative adult departments. They knew, however, that BCH did incur higher costs fulfill its substantial research and teaching missions and to care for a significantly more complex and resource-intensive patient population. BCH had been experimenting with new reimbursement approaches and, in 2012, became the first pediatric hospital to enter into an Alternative Quality Contract (AQC) with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts. This three-year AQC signaled a shift from fee-for-service reimbursement to fixed payments with additional rewards based on savings generated and quality targets reached. The contract specified no rate increases for 2012 and modest increases below inflation for the remainder of the agreement. Other public and private payors were also approaching BCH to negotiate bundled payments that would cover whole episodes of care that would replace traditional fee-for-service reimbursements. The RCC method first collected all the charges produced by a revenue-producing clinical department, such as Orthopaedic Surgery. It then aggregated all the department's traceable expenses, such as the costs of personnel compensation, equipment , supplies, information systems, and billing. To these, it added the hospital's allocations of shared costs-such as for utilities, space, and housekeeping-to the department. The method divided the sum of all departmental traceable and allocated costs by the department's total charges to calculate the department's RCC rate. To calculate the cost of any particular departmental procedure or intervention, it multiplied the procedure's charge by the department's RCC rate. For example, a department with total costs of $4.2 million and total annual charges of $7.0 million would have an RCC of 0.6. The cost of any single billable event was estimated by multiplying the procedure's charge, say $800, by the RCC (for a cost of $480). The charges in the RCC calculation came from physician practices' charge masters, in effect, the "list prices" for these services, which were based on physician fee schedules established by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) (see Exhibit 5). Tufts network estimated an average of $6,000 lower per comparable admission. Martha Coakley's 2008 report estimated that BCH was paid almost twice as much per patient as Floating for similar care; but these figures are averages not adjusted for the complexity of patients Many hospital units also used the RCC method to assign departmental costs to procedures and services. Some used a more sophisticated and complex allocation method based on internally-derived Relative Value Units (RVU). 3 914-407 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery BCH's Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery (DPOS) provided comprehensive care for a wide variety of congenital and acquired conditions. As one of the largest pediatric plastic and oral surgery centers in the country, it performed over 3,000 surgical procedures and handled more than 14,000 outpatient visits each year. The DPOS also had a comprehensive research program, and continually translated the knowledge gained in its scientific laboratories into improved clinical care. Dr. John Meara, Chief of the DPOS, had joined BCH in 2006 after spending several years practicing in Australia where he had also earned his MBA. Anticipating the potential introduction of new reimbursement models at the state and national level, Meara had attended Professor Michael Porter's value-based health care delivery course at Harvard Business School (HBS) in 2009. Inspired by the course, Meara launched a project aimed at measuring clinical outcomes and costs in his sub- specialty, cleft and craniofacial surgery. Meara felt that more accurate cost information would help him re-design care processes and improve the pricing for DPOS services. Meara used the DPOS Foundation's RCC system and BCH's Hospital Cost RVU-based costing system to examine the costs of providing care to patients with cleft palates and several other conditions treated in the department. He was surprised to learn that 40% of the costs of the first 18 months of care for certain cleft palate patients were incurred during the few days they spent in the ICU after surgery. Meara described his reaction: Even before I started the project, I knew that a complex patient who went to the ICU cost more. However, I had no idea how much more and what was driving that. For a majority of patients, I was fairly certain that we could get the same quality and safety of care in a "step- down" ward with just a few areas of increased surveillance. I needed to know this kind of information if I were to do anything about reducing costs. In the midst of this study, Meara received a phone call from Porter inquiring as to whether Meara would be interested in testing a new costing approach, time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC), which he and a colleague were initiating in health care. Meara agreed, and he quickly assembled a team to begin the pilot. Dr. Megan Abbott, a resident who had had been working on the project as a research fellow and had also attended the value-based health care delivery course with Meara, agreed to head the new costing project. Meara asked Dr. Von Nguyen, an Internal Medicine physician with an MPH and experience at a major consultancy, to join the team, and Ronald Heald, the department's program administrator and financial manager, to contribute analytical leadership and access to the Foundation's financial information. Meara decided to test the new costing approach in a simple setting, a new patient visit to a plastic surgeon. He selected three conditions encountered in normal practice that represented the full range of potential patient care needs: primary care, simple surgery, and complex surgery (see Exhibit 6). 1. Deformational or positional plagiocephaly was a common disorder characterized by a flattening of the head or face, typically caused by placing an infant in the same position (e.g. on the infant's back) for long periods of time. Plagiocephaly had no known medical repercussions and typically resolved with non-invasive interventions such observation/support, positional advice, or a simple molding helmet. 2. Benign neoplasms of the skin were harmless cutaneous growths that included common skin lesions such as skin cysts, benign skin tumors, and congenital nevi (moles). Physicians typically monitored the appearance and growth patterns of these lesions, but they removed particularly large and bothersome skin growths, as well as nevi that looked suspicious for malignancy. This was done in the office or in the operating room using a simple surgical procedure called an excision 10 3. Craniosynostosis was a deformity that arose when one or more sutures (the fibrous connections that separate the bones of an infant's skull) fused earlier than normal. To the untrained eye, the physical deformity seen in craniosynostosis looked similar to plagiocephaly, but it was actually a far more serious condition that could result in developmental delays and cognitive impairment, as well as secondary neurological complications from high pressure inside the skull. Surgeons usually performed a complex surgical procedure to correct the deformity and reduce intracranial pressure. Despite the variation in treatment complexity for these three conditions, the initial office visit for each was typically coded in the CMS system as a "level-3 visit," carrying a uniform charge of $350. Meara believed, however, that the clinical and administrative work required for patients with craniosynostosis was much greater than for those with plagiocephaly. He felt that the system failed to capture significant nuances in the intensity of care provided for each: Plagiocephaly is a primary care diagnosis-a service that we provide for the local and regional community. It is not a diagnosis upon which to build an academic craniofacial department. Craniosynostosis, on the other hand, is a complex condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach. As an academic surgeon, these are the types of procedures that fascinate us clinically, provide us with challenging research questions, and allow us to teach residents and fellows. The project team collected the data to verify the costing done by the Foundation's existing RCC system. In 2011, the total charges for all plastic surgery patient encounters were $12,449,500, with actual reimbursements considerably lower at approximately $7,967,680 Total clinical and administrative costs for the department (excluding the costs of the surgeons' research and teaching time) were $7,469,700. The Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing (TDABC) Approach The TDABC approach uired a project team to map out every administrative and clinical process involved in the treatment of a medical condition (e.g. craniosynostosis or cleft palate) over a complete care cycle. The care cycle started when the patient first presented for treatment and extended through surgery, recovery, and discharge. The DPOS project's initial focus, however, was only on the initial clinical visit. They wanted to complete the costing quickly and easily so they could compare the TDABC costs of the visits with the RCC cost estimates. The team invited Doris Quinn, a Ph. D. who served as the Director of Process Improvement and Quality Education at MD Anderson Cancer Center (another hospital introducing TDABC for cost measurement), to travel to Boston to train them on how to create condition-specific process maps. The team appended, to each process step, the job classification of the person performing the step and the time required to complete it. Exhibit 7 shows the process maps for the three types of new office visits. as All charge and cost numbers found in this case have been created artificially by the HBS case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual data at BCH 914-107 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-407 Exhibit 1 Boston Children's Hospital Statement of Operations 2011 2010 (In Thousands, S) TDABC also required an estimate of the cost per minute for the clinical and administrative personnel involved in the care process. This ratio, called the capacity cost rate, was obtained by dividing an individual's annual compensation and support costs, such as attributable supervision, HR, IT and occupancy costs) by the total number of minutes per year that the person was available to work with patients. Heald collected data on office expenses and compensation for DPOS's clinical and administrative personnel (see Exhibit 8). Abbott developed a survey to gather information about the number of minutes that physicians had available for patient-related work (see Exhibit 9). She obtained the following data from personnel interviews and surveys: DPOS surgeons had four weeks of vacation, plus ten holiday days and another ten days for professional conferences and training. 2. DPOS surgeons generally worked five days per week and ten hours per day. About 1.2 hours (72 minutes) were taken up with non-clinical meetings and breaks. Of the remaining time, about 25% was for research and teaching, leaving 75% for clinical work. 3. Non-physician personnel had two weeks of vacation, ten holiday days, five days for sick and personal leave, and five training days. 4. Non-physician personnel worked eight-hour days, with an average of 1.5 hours per day used for breaks and training She summarized her interview and survey results in Exhibit 10. Revenues Net patient services revenue Research grants and contracts Recovery of indirect costs on grants and contracts Other operating revenue Medical Center support for mission-related activities Unrestricted contributions, net of fundraising expenses Net assets released from restrictions used for operations Total revenues 1,000,371 162.851 58.786 35,561 18.000 7,243 45.282 1,328,094 1.008,566 144,016 52,311 31,087 16,343 5,132 42.855 1,300,310 1. 551,349 401 275 162.851 Expenses Salaries and benefits Supplies and other expenses Direct research expenses of grants Provision for uncollectible accounts Health Safety Net Trust assessment Depreciation and amortization Interest and net interest rate swap Total expenses 24,094 8,925 88,522 29.625 1,266,641 547,062 410.391 144,016 17,751 9,964 90,942 27,577 1.247,703 The Way Forward Meara met with his project team to review the findings from the TDABC pilot project, which showed considerable differences between the costs and margins calculated by the TDABC approach and those produced by the Foundation's existing cost systems. Dr. Meara and his team wondered about the causes of the discrepancies. Meara re-stated his belief that innovative payment models could not be implemented with poor costing information: With reimbursement models, such as bundled payments, you will be burned if you don't know your costs. How can you offer a bundled all-in price if you don't know what your procedures truly cost and what drives those costs? As he prepared for an upcoming meeting of the Enterprise Costing Workgroup, a multidisciplinary team representing multiple hospital and clinical departments, Meara considered what to recommend. Gain from current operations Changes in estimates of prior year third-party settlements Gain from current operations 61.453 4,970 66.423 52,607 10,413 63,020 Source: Company documents 6 7 914-107 -12- Exhibit7 Process Maps: Office Visits to Department of Plastic Surgery Plagiocephaly Check in with ASR Peuwe PORT and weight Tube Bilary cw pelin documenter 20 Hence Check out Consult with MO (15 Simple Skin Excision local dat prechein Prap, takata rasm, hent and with Take itary document Comitwist MD bplain didel TA call to schedule 1-10 com Hling - patient Check-our 59 Craniosynostosis Take history Check in with ASR Prentar on leche and weight a photo Pull upcy Aran Conut with MD M reteria Check out Key: Clinical A Registered Phrysan Service Represente Yemen Minutes Source: Casewriter analysis. Time estimates have been disguised for case purposes and do not represent actual times at BCH 914-107-13- Exhibit 8 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery: Cost Analysis $ Ambulatory Service Registered Representative Nurse Clinical Surgeon (ASR) (RN) Assistant (CA) Total 5,500,000 $ 390,000 $1,098,500 $ 235,300 $ 7,223,800 220,000 220,000 760,000 760,000 400,000 148,200 247,000 123,500 918,700 6,880,000 $ 538,200 $ 1,345,500 $ 358,800 $ 9,122,500 25% 0 75% 0 0 5,160,000 0 67,200 0 5,227,200 $ 538,200 $ 1,345,500 $ 358,800 $ 7,469,700 10 6 10 5 31.0 522,720 $ 89,700 $ 134,550 $ 71,760 Compensation: Salary, Fringes and Bonus Malpractice Insurance Billing Services Office expenses: rent, utilities, insurance, supplies Total Research and teaching time Clinical time Surgeon clinical expenses Medical Supplies Total Clinical Costs Number of employees Clinical cost per employee $ $ $ Source: Casewriter analysis. All cost numbers in this case have been created artificially by the case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual cost data of the organization 914--07 Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) Boston Children's Hospital: Measuring Patient Costs (Abridged) 914-107 Exhibit 9 Physician Time Sheet Exhibit 10 Department of Plastic and Oral Surgery: Available Time Worksheet Resource ASR RN CA NAME: : DATE: 52 52 4 DEPARTMENT: PLASTIC AND ORAL SURGERY Surgeon 52 6 2 44 Weeks per year Less: Vacation & Holidays Less: Training and Leave Available weeks per year 4 2 2 52 4 2 2 For each day in a typical work week, please estimate the number of hours spent on the following activities. If in clinic without resident, then place hours under clinic; if in clinic with resident, then place hours under clinic + education; if at grand rounds, then place hours under education. 46 46 46 8 8 10 1.2 8 1.5 1.5 1.5 ACTIVITY: CLINIC CLINIC EDUCATION SURGERY SURGERY EDUCATION OTHER EDUCATION PATIENT OUTSIDE CARE CLINIC/OR RESEARCH ADMIN Hours per day Less: Breaks, training meetings Available hours per day Less: Estimate of Research & Education time % Clinical Hours per day 65 Mutually exclusive categories 8.8 25% 6.6 6.5 0% 6.5 6.5 0% 6.5 0% 6.5 Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Source: Casewriter analysis. All cost numbers found in this case have been created artificially by the case writers for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual cost data of the organization. Friday Saturday Sunday Number of weeks or days per year on vacation or away at conferences, on average Clinie: Block hours in line without resident or medical student Clinie Education: Block hours in elinie with resident of medical student Surgery: Block hours in OR plus time in pee-por PACU that would not be included in block time (Lc. if you get there early or stay late routinely): without residents or medical students Surgery + Education: Block hours in OR plus time in pre-op or PACU that would not be in the block time te. if you get there early or stay late routinely with residents or medical students Other patient care: Hours spent on any activity, including dictation, notes, e- mail, phone calls (to patients or consulting providers) reading journals/textbooks, that contributes to care of specific patients, getside of block times some consider this as practice management Education: Hours spent in education outside of block time, including grand rounds attendance, medical school lectures, preparation of talks, mentoring students, etc. Research: Hours spent thinking/reading about research, discussing research, or performing research Admin: Hours spent in administrative meetings, deciding and implementing departmental changes, working with non-clinical staff, marketing, paperwork for non-clinical activities, ete, can average over months or weeks Source: Company documents. 14 15