use the given case study to answer the questions in the context of cost-benefit analysis.

a. If you were running a state welfare agency and had to choose to implement one of the types of programs listed in the table, in which order of priority would you consider the information contained in the table's columns? Why?

b. If you were running a state welfare agency, what information would you like to have in addition to that provided in the table? Could the new information change your previous choice? If yes, how? If no, why?

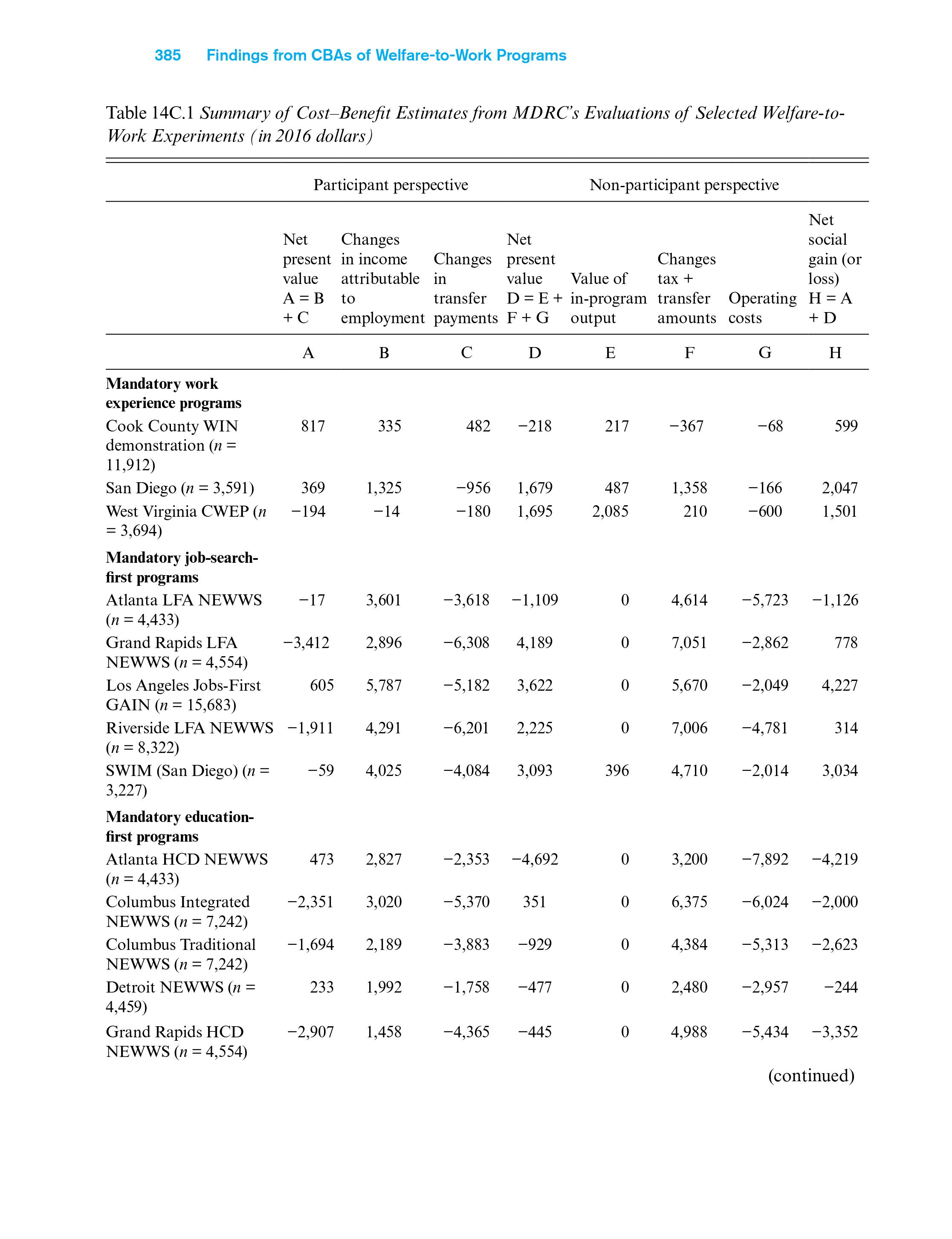

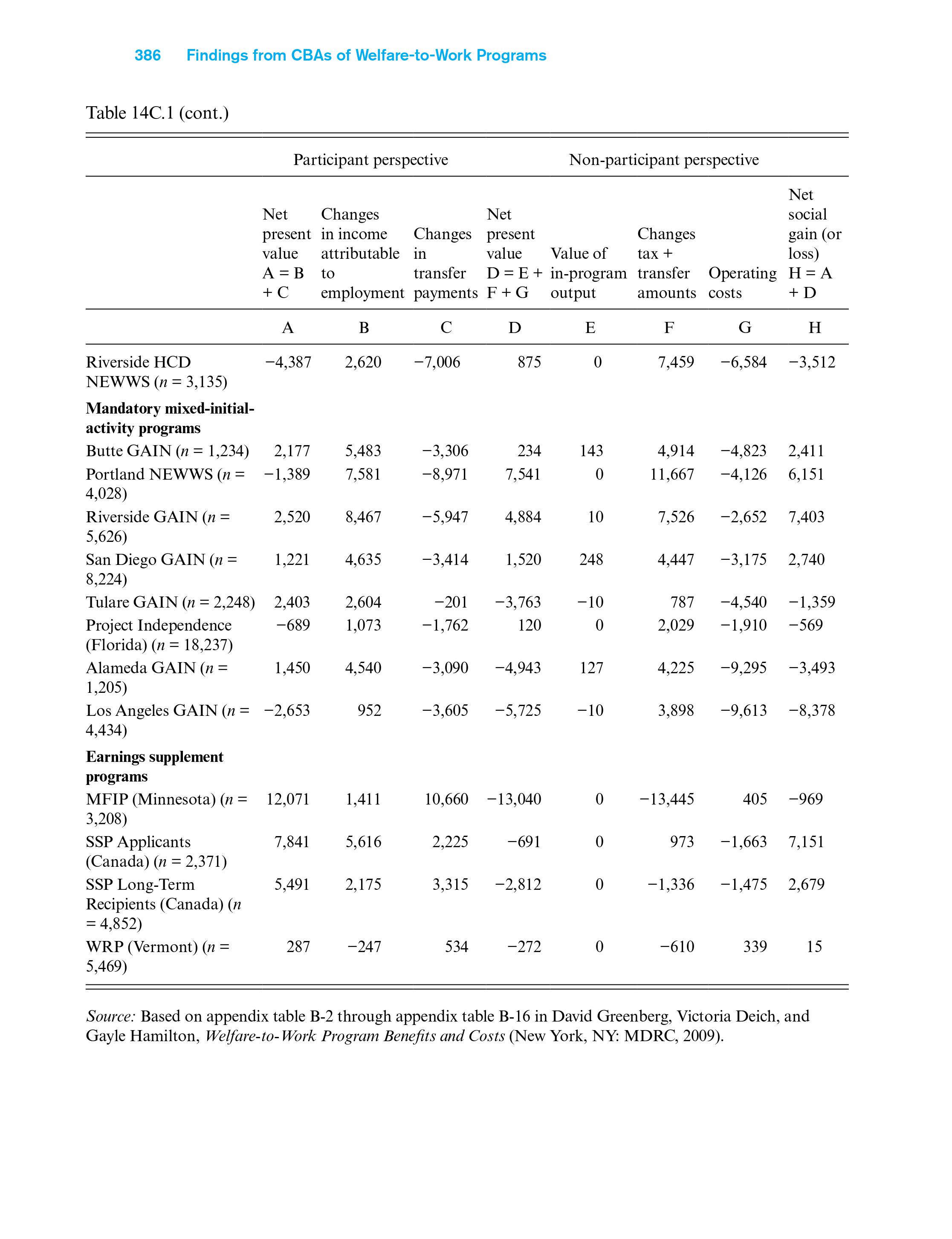

Findings from CBAs of Welfare-to- C'laje Work Programs Table 14C.l, which appears at the end of this case, presents summary results from CBAs of 26 welfare-to-work programs.1 These programs were all targeted at single parents who participated in the Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which at the time the CBAs were conducted was the major cash welfare program in the United States. Most of the programs were mandatory in the sense that AFDC benets could be reduced or even terminated if a parent did not cooperate. The CBAs were all conducted by MDRC, a well-known non-prot research rm, and used a similar framework includ- ing the classical experimental design with random assignment to treatment and control groups. The estimates in the table, which have been converted to 2016 dollar amounts using the US Consumer Price Index, should be viewed as program impacts on a typical member of the treatment group in each of the listed programs. The rst three columns in the table present estimated benets and costs from the participant perspective and the next four from the non-participant perspective. Columns A and D, respectively, report total net gains (or losses) from these two perspectives, while columns B, C, E, F, and G provide information on the benet and cost components that together account for these gains (or losses). For example, column B reports the estimated net gain by participants from employment under each program, that is, estimates of the sum of increases in earnings, fringe benets, and any work-related allowances paid under the program less the sum of tax payments and participant job-required expenditures on child care and transportation. Column C indicates changes in AFDC and other transfer benets received by participants. Column E presents MDRC's valuations of in-program output. Column F is the sum of tax increases paid by participants, reductions in transfer payments paid to participants, and reductions in transfer program operating costs, all of which may be viewed as benets to non-participants. Column G shows the government's cost of operating the treatment programs. Finally, column H, which is computed by sum- ming the benetcost components reported in columns B, C, E, F, and G, presents the overall CBA results from the perspective of society as a whole. As can be seen from column H, 15 of the 26 reported estimates indicate overall net gains and 11 imply net losses. Nonetheless, most of the total net gains and losses for either participants or non-participants that are implied by columns A and D are not especially large; all but six are well under $4,000 per program participant in 2016 dollars. The table distinguishes between ve distinct types of welfare-to-work programs. As summarized below, the costs and benets for different program types vary considera- bly and are quite relevant to policy. 384 Findings from CBAs of Welfare-to-Work Programs Mandatory work experience programs, which assigned welfare recipients to unpaid jobs, appear to be worthy of consideration as a component of a compre- hensive welfare-to-work program. These programs were implemented for per- sons who, after a period of time searching, could not find unsubsidized jobs. The programs are not costly to the government and do little harm to participants. Moreover, society as a whole can reap some benefit from the output produced at work experience jobs. . Mandatory job-search-first programs require individuals to look for jobs imme- diately upon being assigned to the program. If work is not found, then they are assigned other activities. Such programs appear worthy of consideration when governments want to reduce their expenditures. The programs tend to be less expensive than mandatory mixed-initial-activity programs and, thus, to have a more salutary effect on government budgets. However, they are unlikely to increase the incomes of those required to participate in them. The sorts of mandatory education-first programs that have been tested experi- mentally - ones that require individuals to participate in GED completion and Adult Basic Education prior to job search - do not appear to offer positive net benefits. They do little to either increase the incomes of participants or save the government money. . Mandatory mixed-initial-activity programs require individuals to participate initially in either an education or training activity or a job search activity. The first six of these programs that are listed in the table enrolled both short-term and long-term welfare recipients, while the last two enrolled only long-term wel- fare recipients. Four of the former were cost-beneficial from a societal perspec- tive, but the latter two were not. . Earnings supplement programs provide individuals with financial incentives or earnings supplements intended to encourage work. The CBA findings suggest that they are an efficient mechanism for transferring income to low-income fam- ilies because participants gain more than a dollar for every dollar the govern- ment spends.385 Findings from CBAs of Welfare-to-Work Programs Table 14C.1 Summary of Cost-Benefit Estimates from MDRC's Evaluations of Selected Welfare-to- Work Experiments ( in 2016 dollars) Participant perspective Non-participant perspective Net Net Changes Net social present in income Changes present Changes gain (or value attributable in value Value of tax + loss) A = B to transfer D = E + in-program transfer Operating H = A + C employment payments F + G output amounts costs + D A B C D E F G H Mandatory work experience programs Cook County WIN 817 335 482 -218 217 -367 -68 599 demonstration (n = 11,912) San Diego (n = 3,591) 369 1,325 -956 1,679 487 1,358 -166 2,047 West Virginia CWEP (n -194 -14 -180 1,695 2,085 210 -600 1,501 = 3,694) Mandatory job-search- first programs Atlanta LFA NEWWS -17 3,601 -3,618 -1,109 O 4, 614 -5,723 -1,126 (n = 4,433) Grand Rapids LFA -3,412 2,896 -6,308 4,189 O 7,051 -2,862 778 NEWWS (n = 4,554) Los Angeles Jobs-First 605 5, 787 -5,182 3,622 O 5.670 -2,049 4,227 GAIN (n = 15,683) Riverside LFA NEWWS -1,911 4,291 -6,201 2,225 0 7,006 -4,781 314 (n = 8,322) SWIM (San Diego) (n = -59 4,025 -4,084 3,093 396 4.710 -2,014 3.034 3,227) Mandatory education- first programs Atlanta HCD NEWWS 473 2,827 -2,353 -4,692 O 3,200 -7,892 -4,219 (n = 4,433) Columbus Integrated -2,351 3,020 -5,370 351 O 6,375 -6,024 -2,000 NEWWS (n = 7,242) Columbus Traditional -1,694 2, 189 -3,883 -929 O 4.384 -5,313 -2,623 NEWWS (n = 7,242) Detroit NEWWS (n = 233 1,992 -1,758 -477 O 2,480 -2,957 -244 4,459) Grand Rapids HCD -2,907 1,458 -4,365 -445 0 4,988 -5,434 -3,352 NEWWS (n = 4,554) (continued)386 Findings from CBAs of Welfare-to-Work Programs Table 14C. 1 (cont.) Participant perspective Non-participant perspective Net Net Changes Net social present in income Changes present Changes gain (or value attributable in value Value of tax + loss) A =B t transfer D = E + in-program transfer Operating H = A + C employment payments F + G output amounts costs + D A B C D E F G H Riverside HCD -4,387 2,620 -7,006 875 0 7,459 -6,584 -3,512 NEWWS (n = 3,135) Mandatory mixed-initial- activity programs Butte GAIN (n = 1,234) 2,177 5,483 -3,306 234 143 4,914 -4,823 2,411 Portland NEWWS (n = -1,389 7,581 -8,971 7,541 11,667 -4,126 6,151 4,028) Riverside GAIN (n = 2,520 8,467 -5,947 4,884 10 7,526 -2,652 7,403 5,626) San Diego GAIN (n = 1,221 4,635 -3,414 1,520 248 4.447 -3,175 2,740 8,224) Tulare GAIN (n = 2,248) 2,403 2,604 -201 -3,763 10 787 -4,540 -1,359 Project Independence -689 1,073 -1,762 120 0 2,029 -1,910 -569 (Florida) (n = 18,237) Alameda GAIN (n = 1,450 4,540 -3,090 -4,943 127 4,225 -9,295 -3,493 1,205) Los Angeles GAIN (n = -2,653 952 -3,605 -5,725 -10 3,898 -9,613 -8,378 4,434) Earnings supplement programs MFIP (Minnesota) (n = 12,071 1,411 10,660 -13,040 0 -13,445 405 -969 3,208) SSP Applicants 7,841 5,616 2.225 -69 O 973 -1,663 7,151 (Canada) (n = 2,371) SSP Long-Term 5,491 2, 175 3,315 -2,812 0 -1,336 -1,475 2,679 Recipients (Canada) (n = 4,852) WRP (Vermont) (n = 287 -247 534 -272 0 -610 339 15 5,469) Source: Based on appendix table B-2 through appendix table B-16 in David Greenberg, Victoria Deich, and Gayle Hamilton, Welfare-to-Work Program Benefits and Costs (New York, NY: MDRC, 2009)