Question: what are some learning ideas that you may apply in your profession, Make a list that you will maintain to help you in the future

what are some learning ideas that you may apply in your profession, Make a list that you will maintain to help you in the future

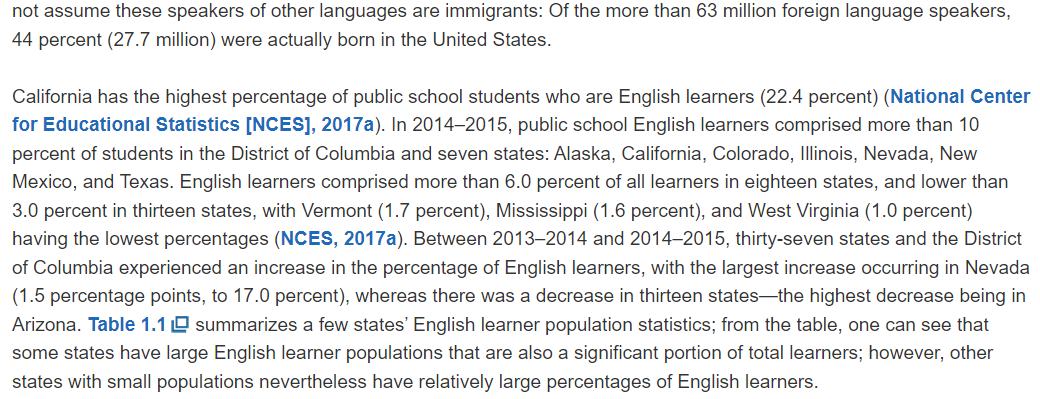

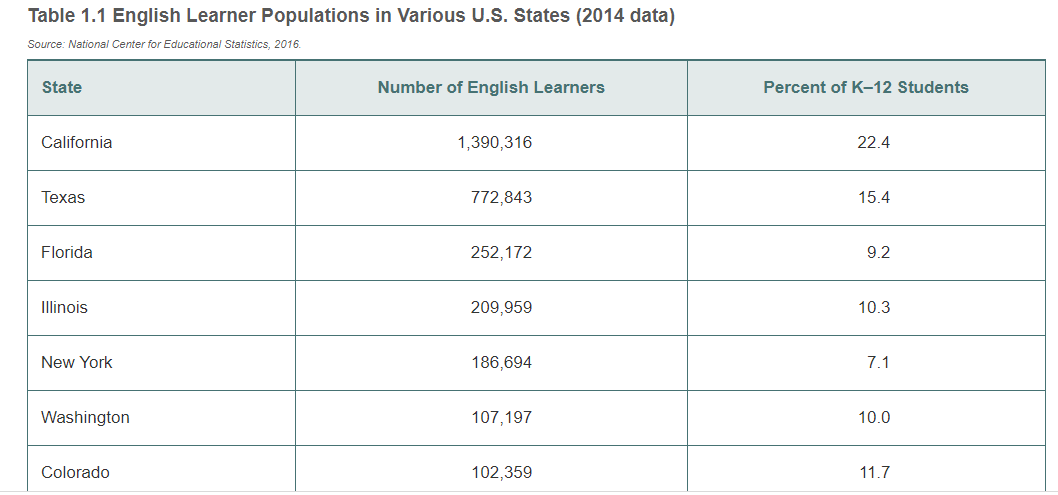

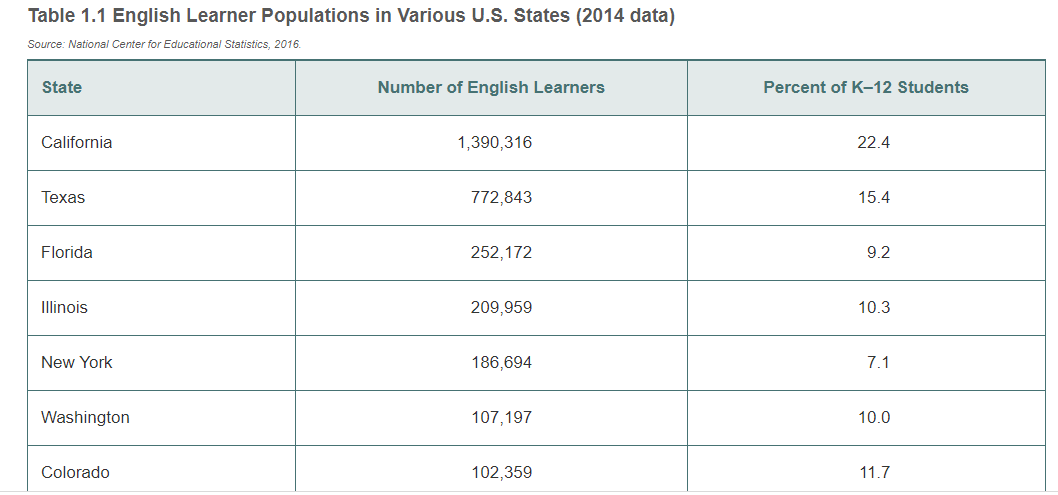

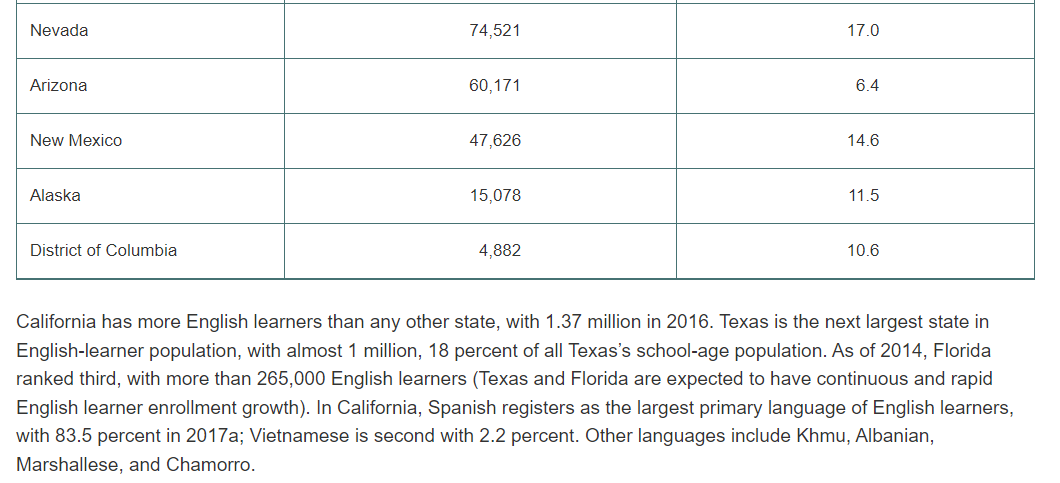

1 English Learners and Their Teachers Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able to ... Compare demographic information about English learners in various U.S. states; Describe what it means to be an ethical teacher of English learners-to "teach with integrity"; and View the gamut of opportunities for teacher preparation to teach English learners. Teaching English Learners Teachers in elementary and secondary schools in the United States face an unprecedented challenge-educating the growing number of students whose families speak a language other than English or whose backgrounds are culturally diverse. In addition to accommodating recently arrived immigrants with limited English proficiency, schools need to offer a high-quality, college-bound curriculum to English-speaking students whose heritage is Native American or other long-time residents of the United States, including those who are long-term English learners and who have not yet achieved the distinction of being transferred out of English-language-development services. In the face of this diverse linguistic and cultural terrain, the responsibilities of U.S. educators have become increasingly complex. Teachers must now modify instruction to meet the specific needs of culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students, especially English learners, using English-language development (ELD) techniques and other instructional adaptations to ensure that all students have access to an excellent education. In turn, educators are finding that these diverse cultures and languages add richness and depth to their teaching experience. Because the core of the teaching profession in the United States remains monolingual, teachers can benefit from teacher education that includes specialized methods and strategies for the effective education of CLD students, especially those who have the potential for becoming fully bilingual. Language learning is a complex process that forms the foundation for academic achievement. Competence in more than one language is a valuable skill. Students who come to school already speaking a home language other than English have the potential to become bilingual if schooling can preserve and augment their native-language proficiency. One exciting trend is the spread of two-way immersion (TWI) programs, which enable monolingual English-speaking students to learn a second language in the company of English learners. This book uses the term English learner to mean "students whose first (primary, native) language is not English and who are learning English at school." This chapter offers an overview of the demographics of English learners, a vision of the ethics involved in teaching English learners, and a view of the educational opportunities in the field of teaching English learners. English Learners in U.S. Schools Demographics of English Learners in the United States The Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) (2017) put the number of English learners (K-12) in the United States at 4.6 million for 2014-2015, about 9.4 percent of all students in grades K-12. In 2015, a record 63.2 million U.S. residents over the age of five spoke a language other than English (LOTE) at home. Across the United States, about one in five pupils in K-12 education goes home to a LOTE household. From 2010 to 2014 the largest percentage increases in LOTE households were among speakers of Arabic (up 29 percent); Urdu (spoken in Pakistan, up 23 percent); Hindi (up 19 percent); Chinese and Hmong (spoken in Laos, both up 12 percent); and Gujarati (spoken in India) and Persian were both up 9 percent (Camarota & Zeigler, 2015). One must not assume these speakers of other languages are immigrants: Of the more than 63 million foreign language speakers, 44 percent (27.7 million) were actually born in the United States. California has the highest percentage of public school students who are English learners (22.4 percent) (National Center for Educational Statistics [NCES], 2017a). In 2014-2015, public school English learners comprised more than 10 percent of students in the District of Columbia and seven states: Alaska, California, Colorado, Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico, and Texas. English learners comprised more than 6.0 percent of all learners in eighteen states, and lower than 3.0 percent in thirteen states, with Vermont (1.7 percent), Mississippi (1.6 percent), and West Virginia (1.0 percent) having the lowest percentages (NCES, 2017a). Between 2013-2014 and 2014-2015, thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia experienced an increase in the percentage of English learners, with the largest increase occurring in Nevada (1.5 percentage points, to 17.0 percent), whereas there was a decrease in thirteen states-the highest decrease being in Arizona. Table 1.1 summarizes a few states' English learner population statistics; from the table, one can see that some states have large English learner populations that are also a significant portion of total learners; however, other states with small populations nevertheless have relatively large percentages of English learners. Table 1.1 English Learner Populations in Various U.S. States (2014 data) Source: National Center for Educational Statistics, 2016. State Number of English Learners California 1,390,316 Texas 772,843 Florida 252,172 Illinois 209,959 New York 186,694 Washington 107,197 Colorado 102,359 Percent of K-12 Students 22.4 15.4 9.2 10.3 7.1 10.0 11.7 Nevada 74,521 17.0 Arizona 60,171 6.4 New Mexico 47,626 14.6 Alaska 15,078 11.5 District of Columbia 4,882 10.6 California has more English learners than any other state, with 1.37 million in 2016. Texas is the next largest state in English-learner population, with almost 1 million, 18 percent of all Texas's school-age population. As of 2014, Florida ranked third, with more than 265,000 English learners (Texas and Florida are expected to have continuous and rapid English learner enrollment growth). In California, Spanish registers as the largest primary language of English learners, with 83.5 percent in 2017a; Vietnamese is second with 2.2 percent. Other languages include Khmu, Albanian, Marshallese, and Chamorro. For more information about U.S. states' English-learner populations and resources, enter

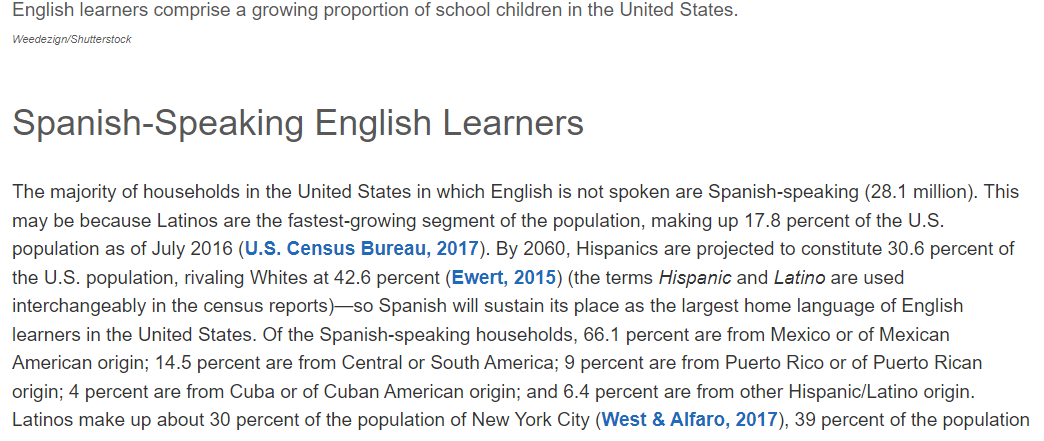

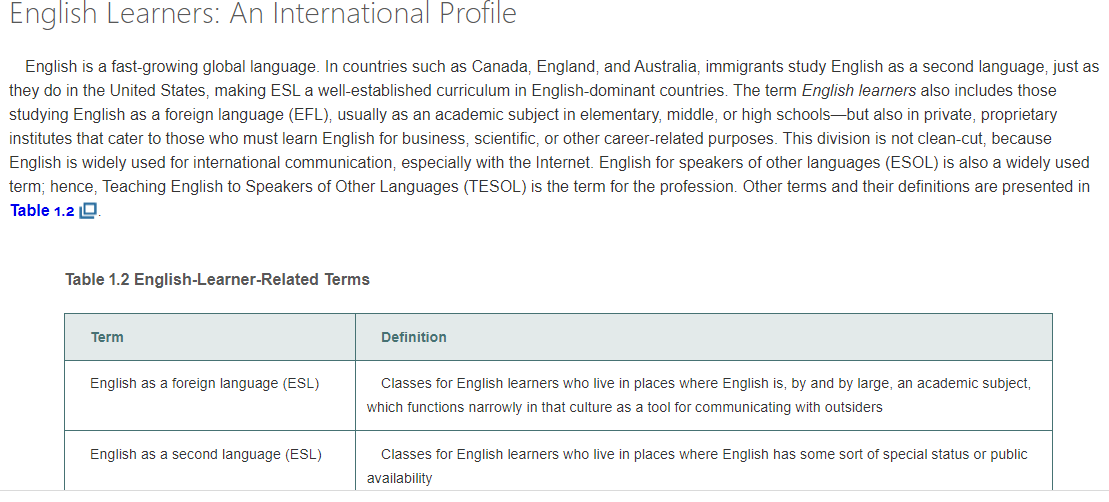

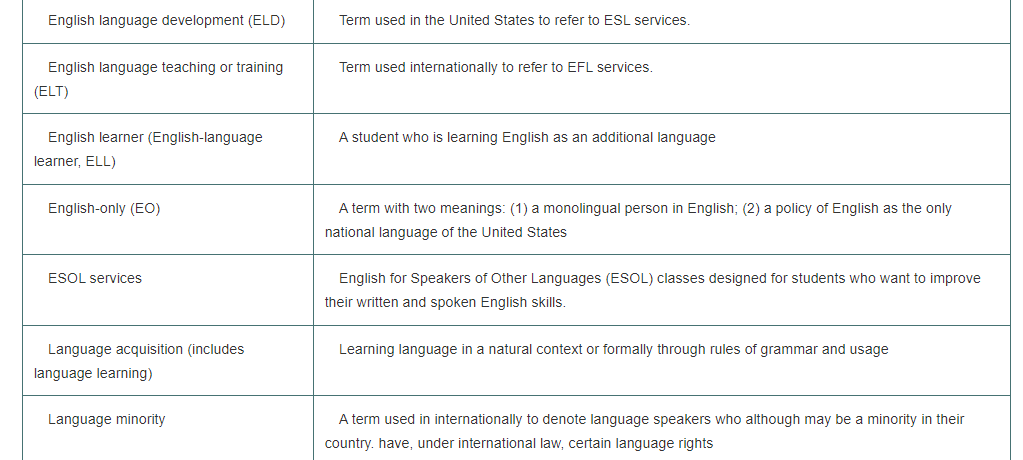

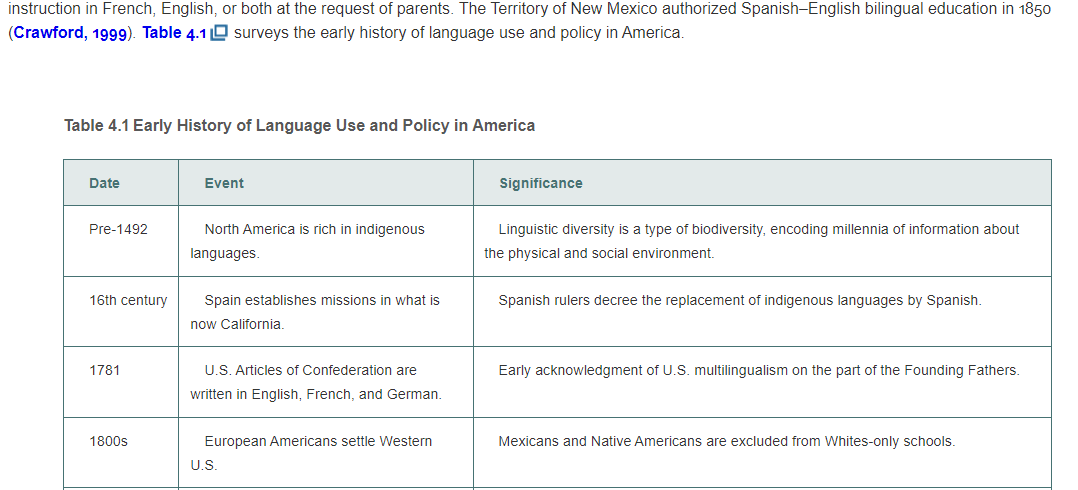

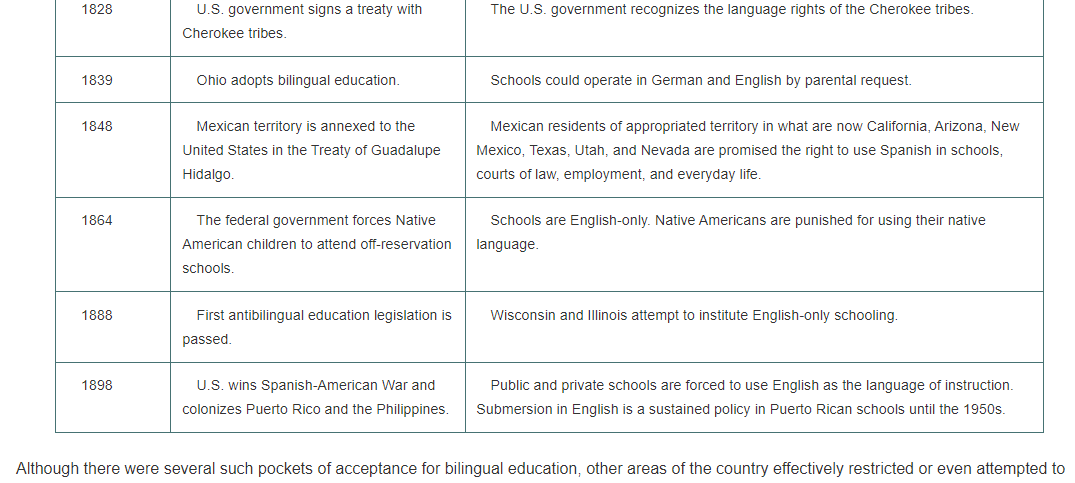

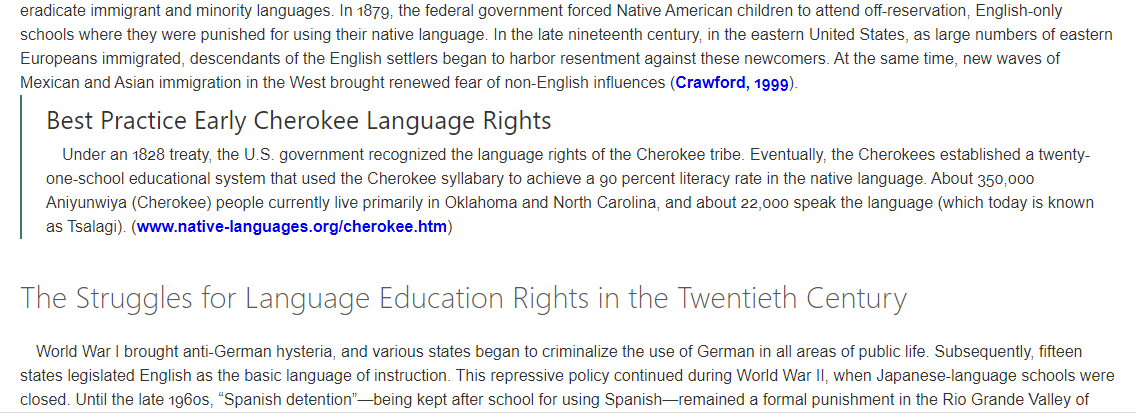

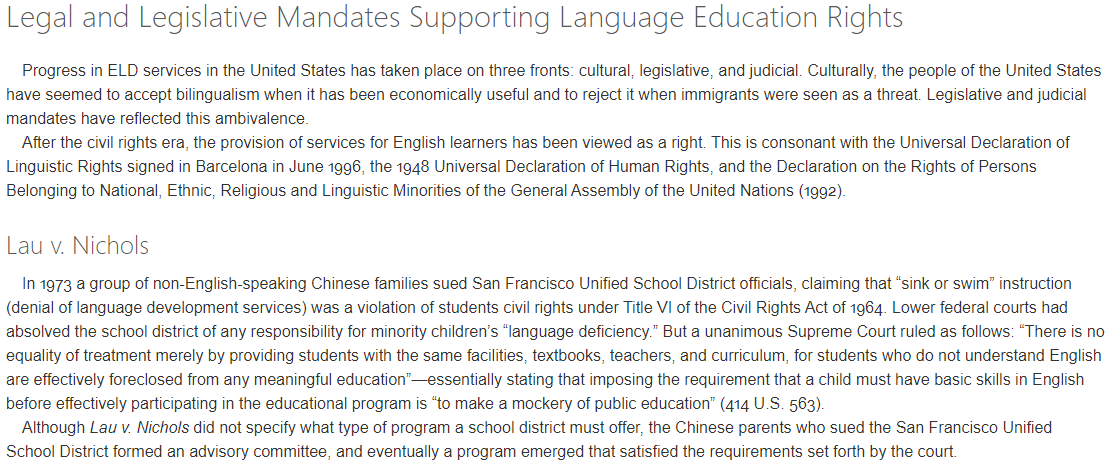

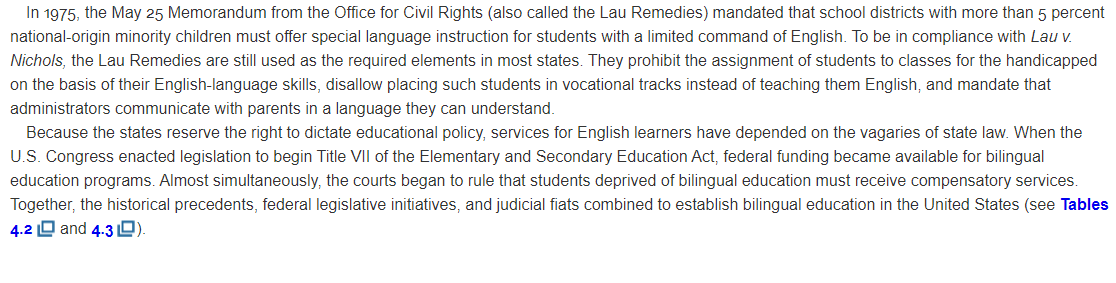

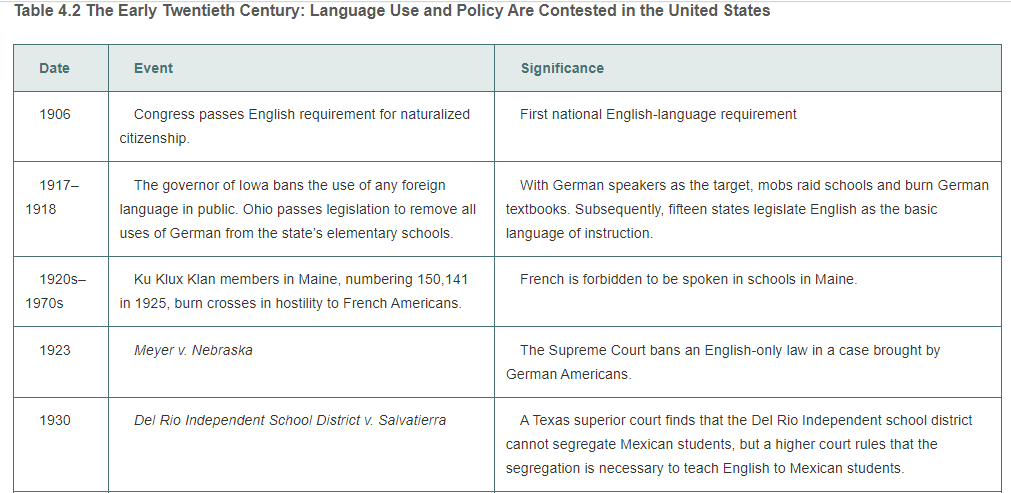

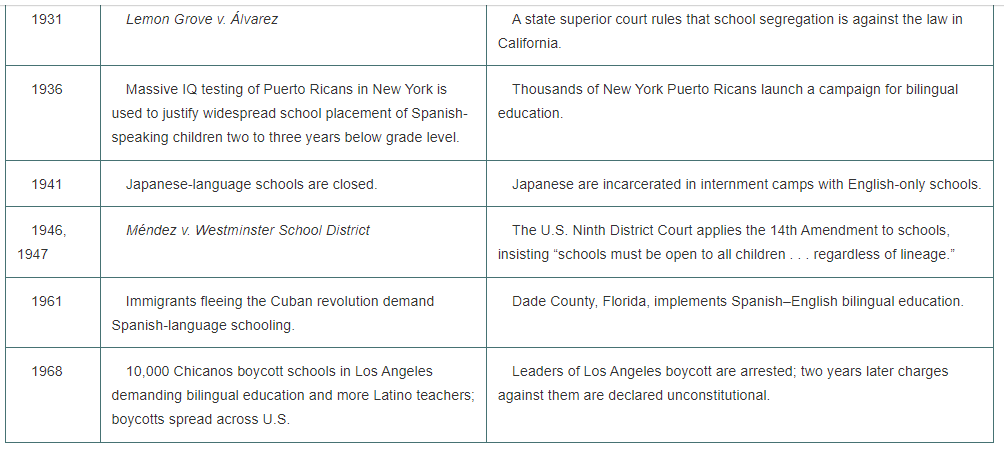

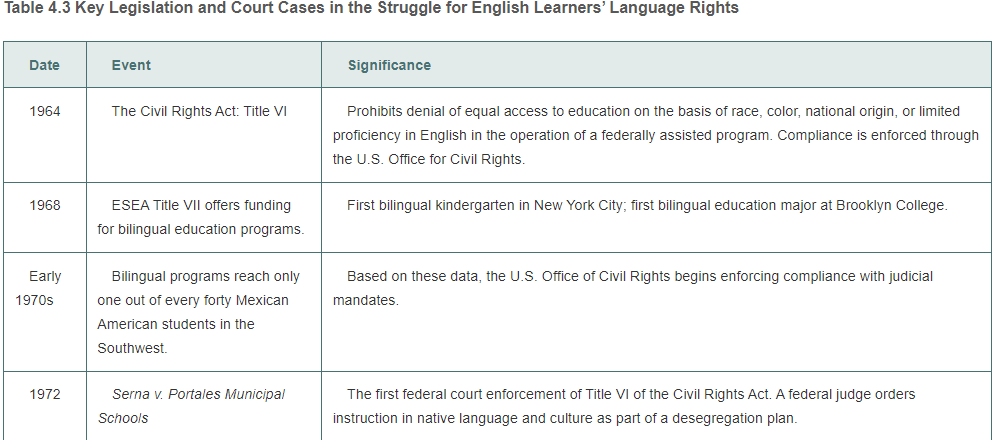

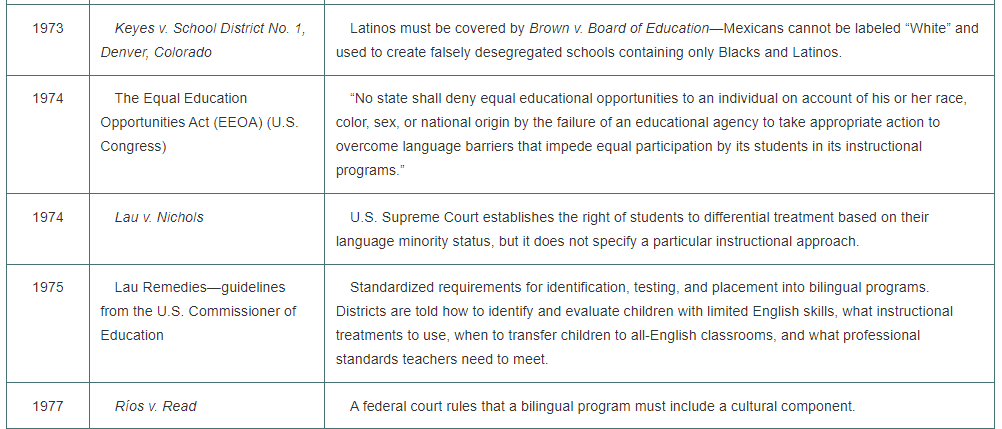

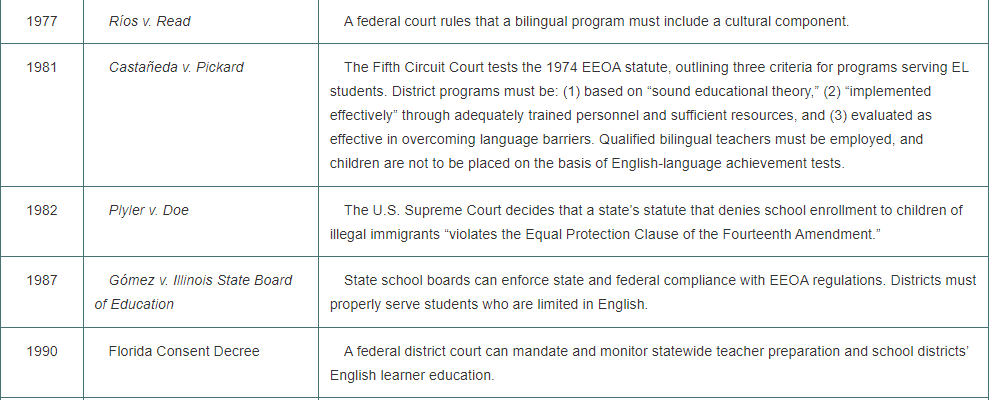

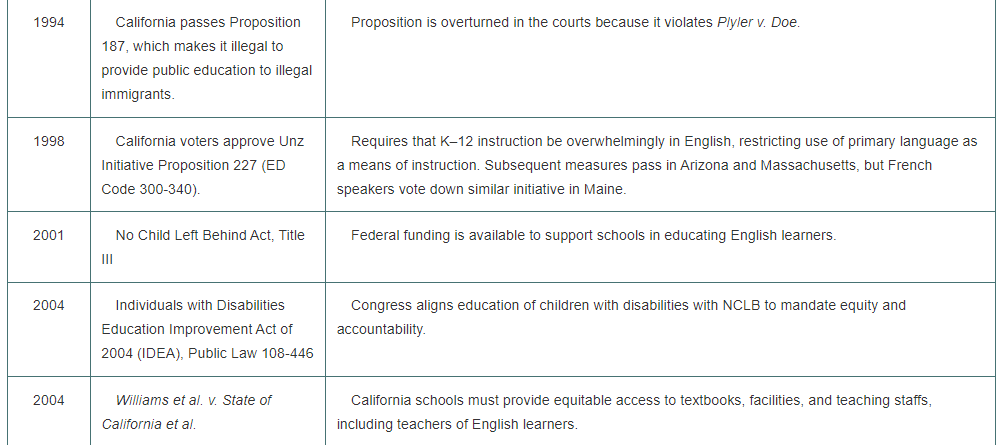

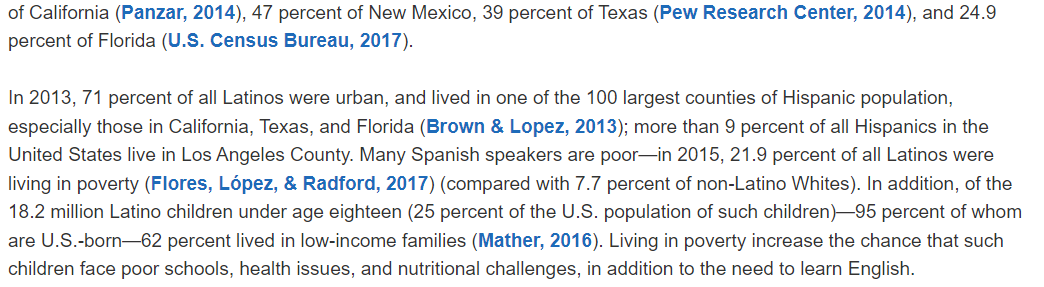

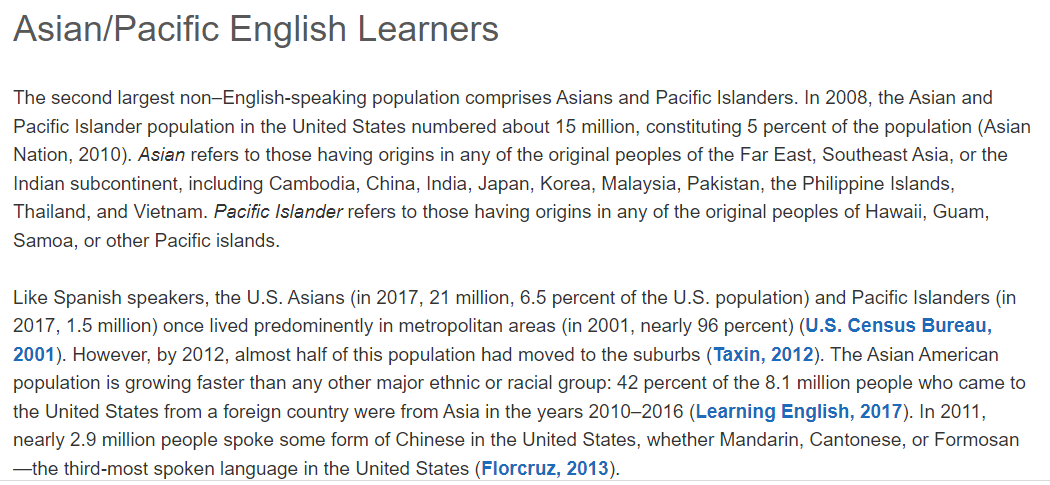

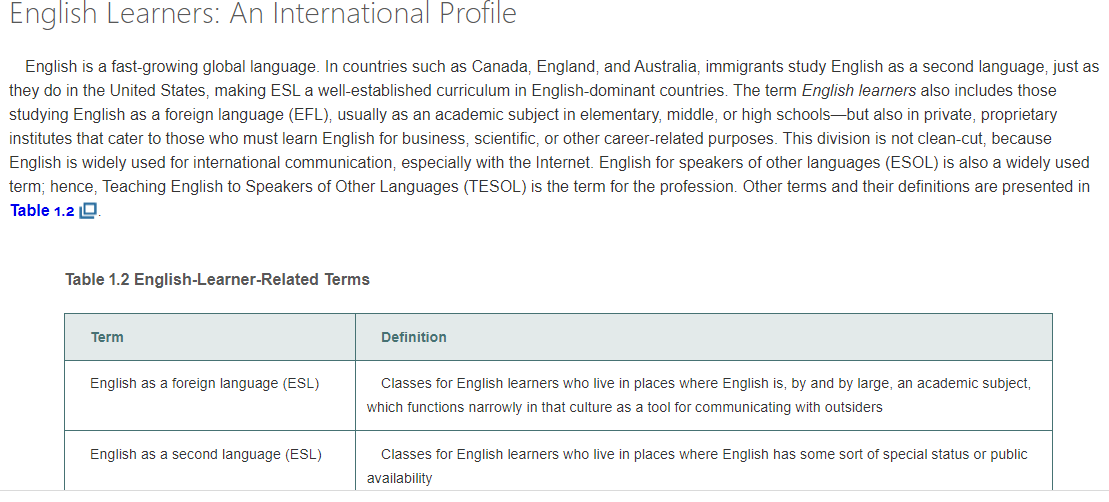

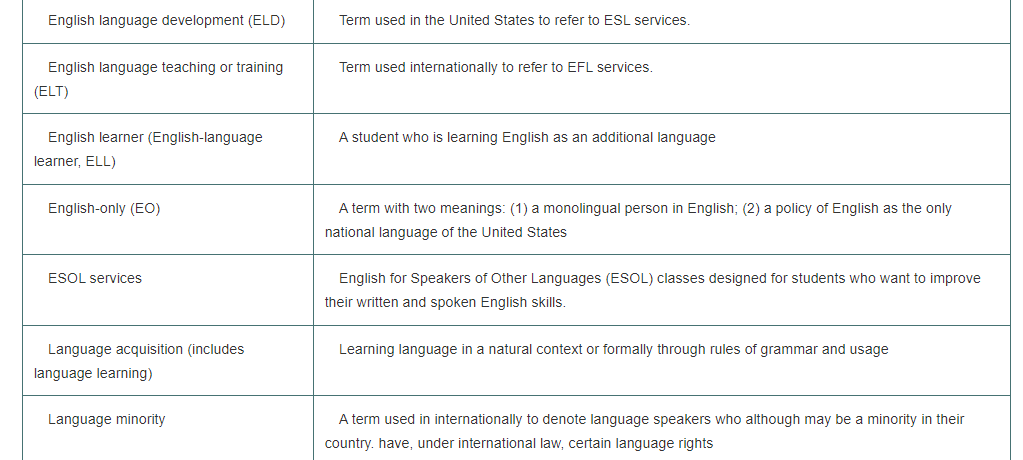

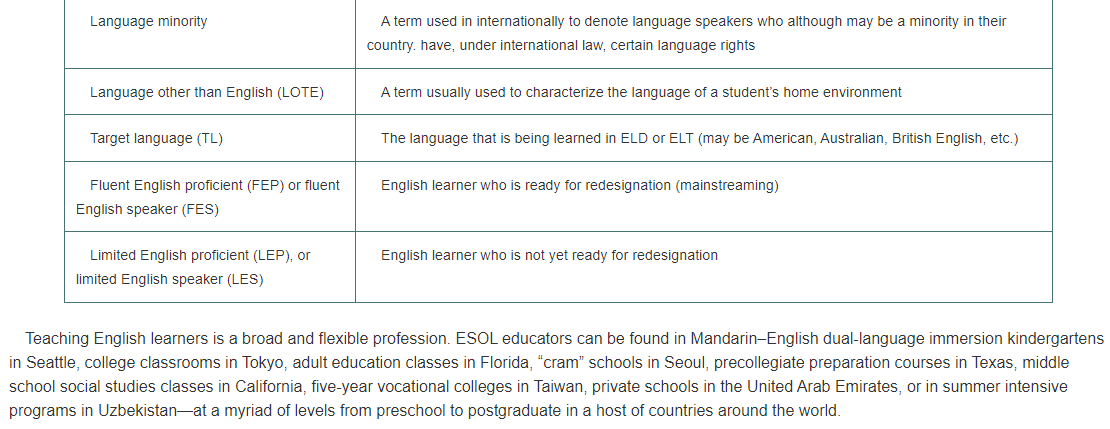

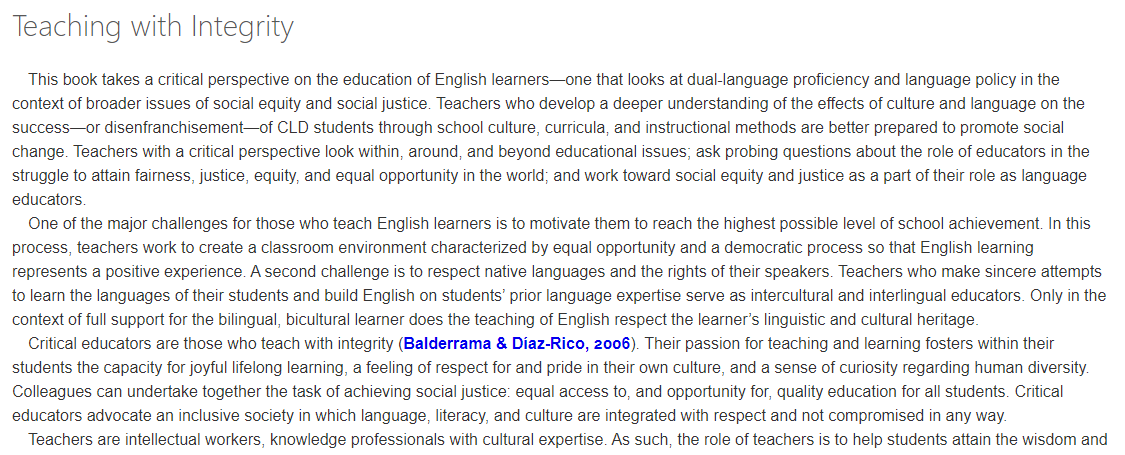

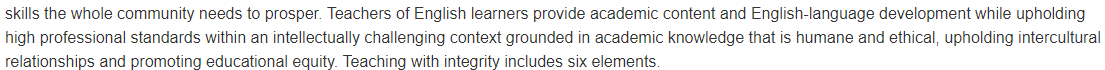

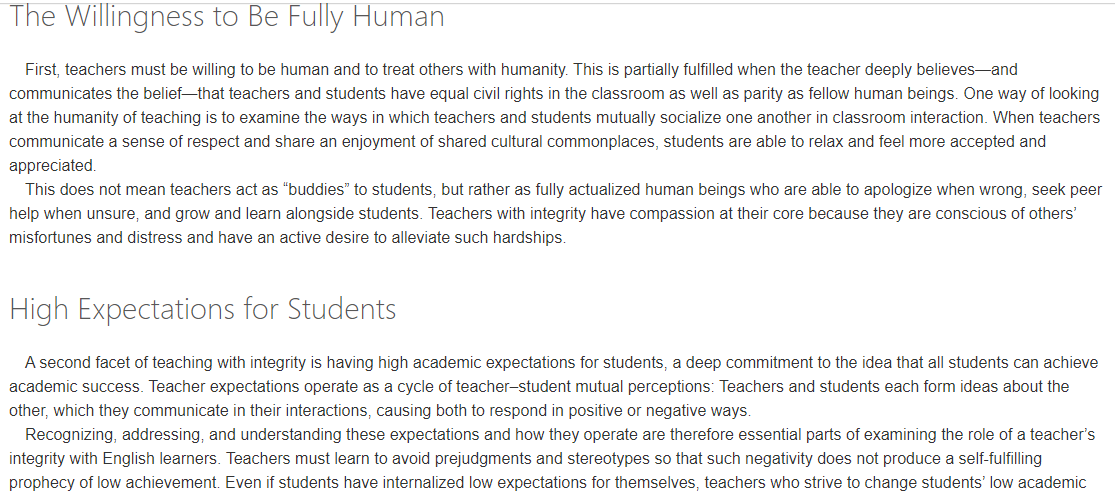

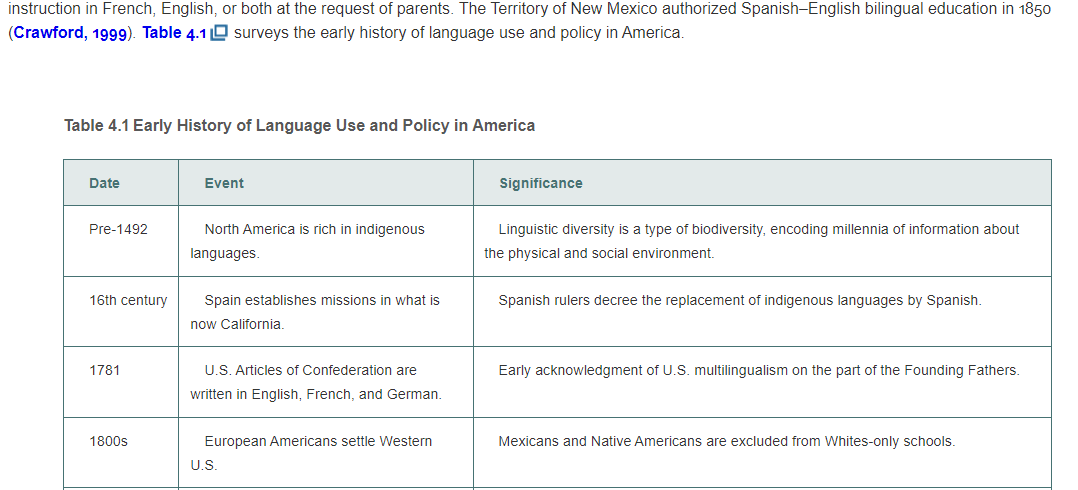

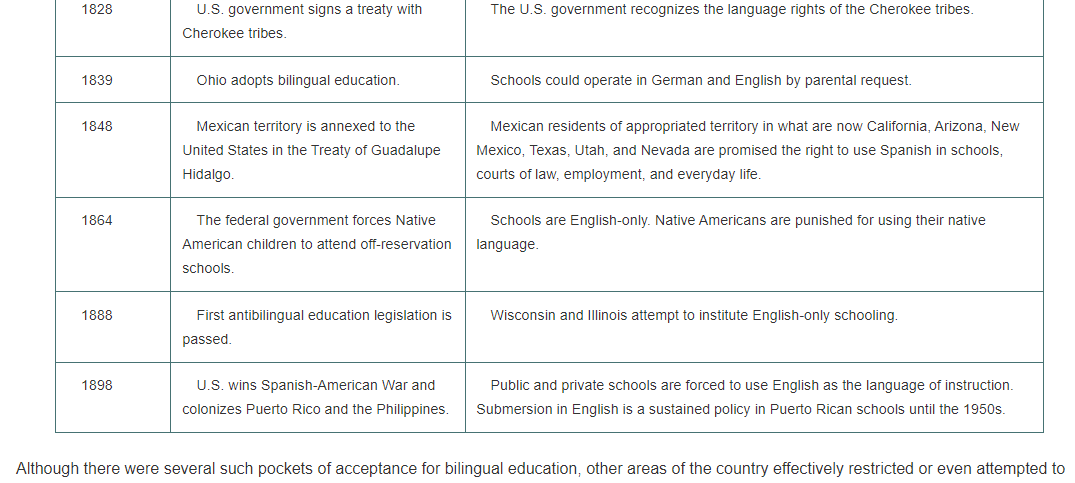

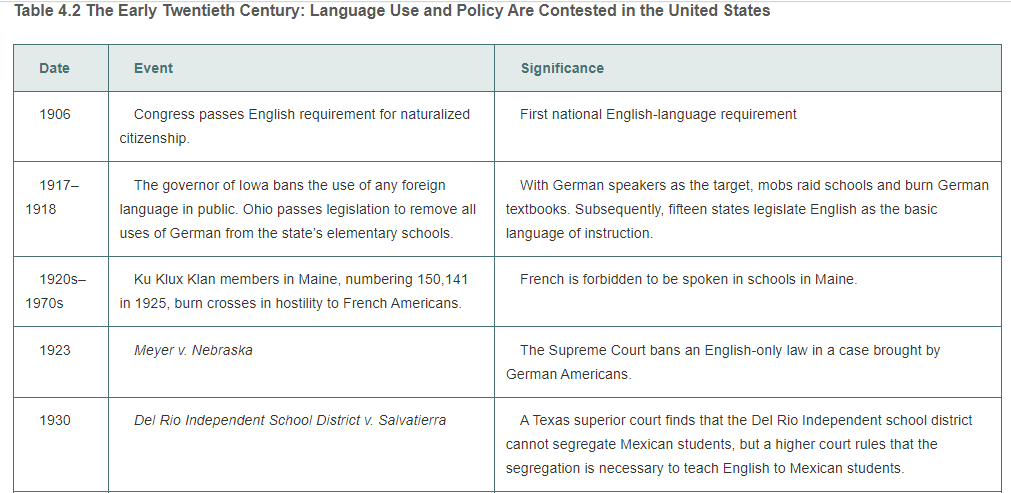

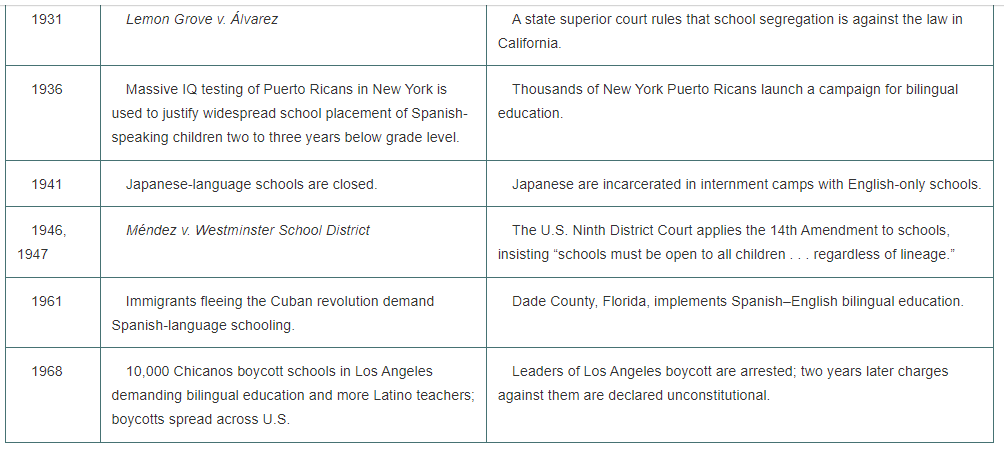

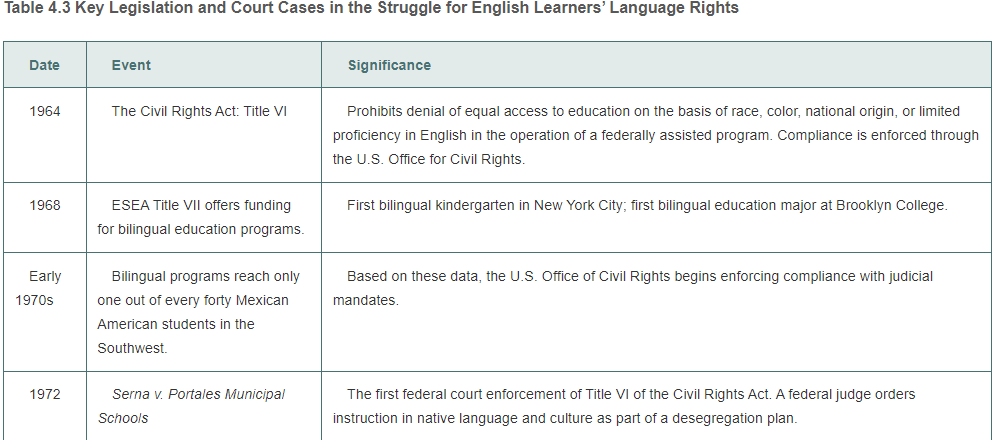

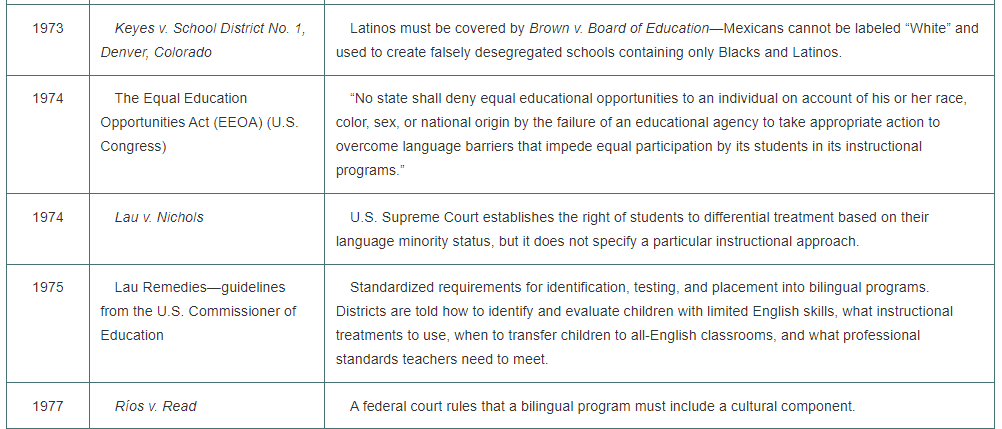

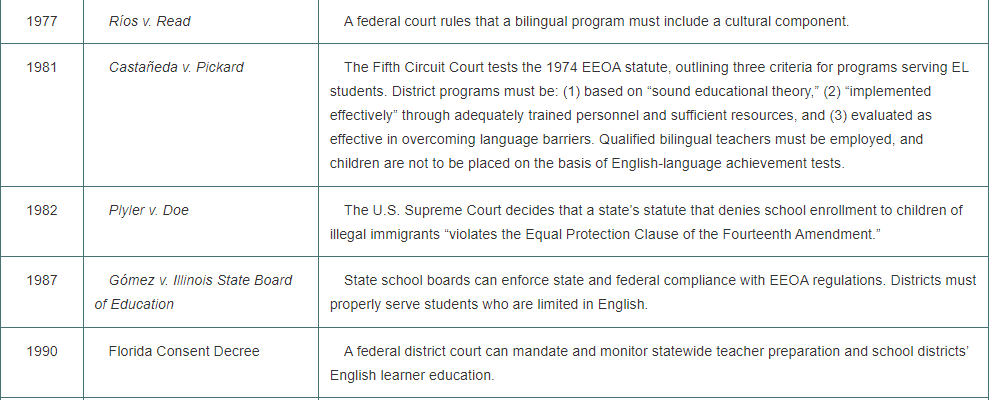

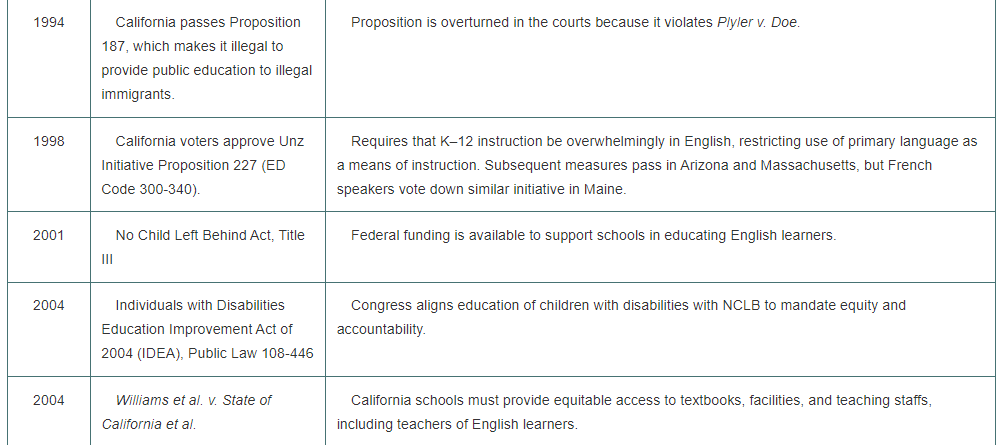

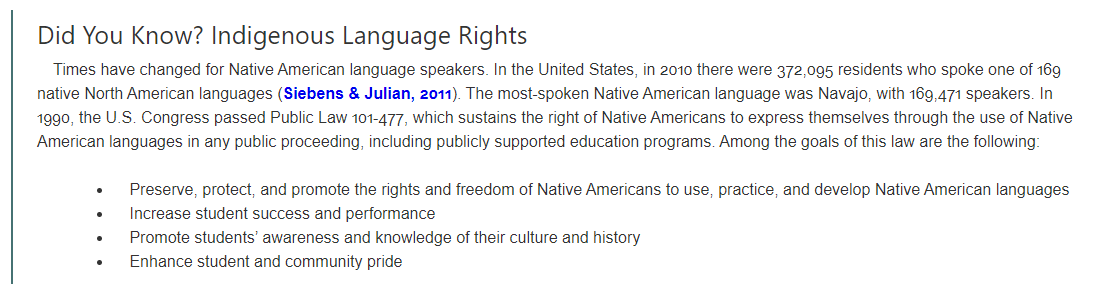

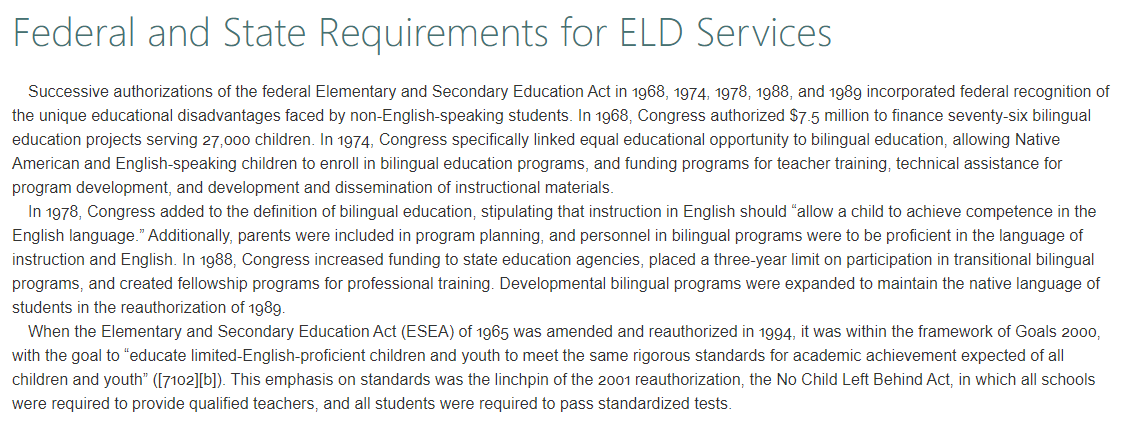

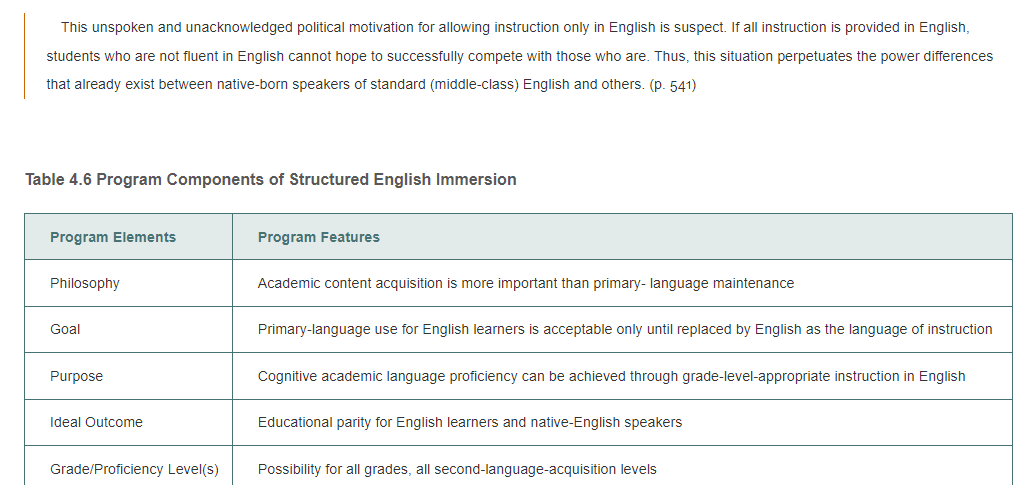

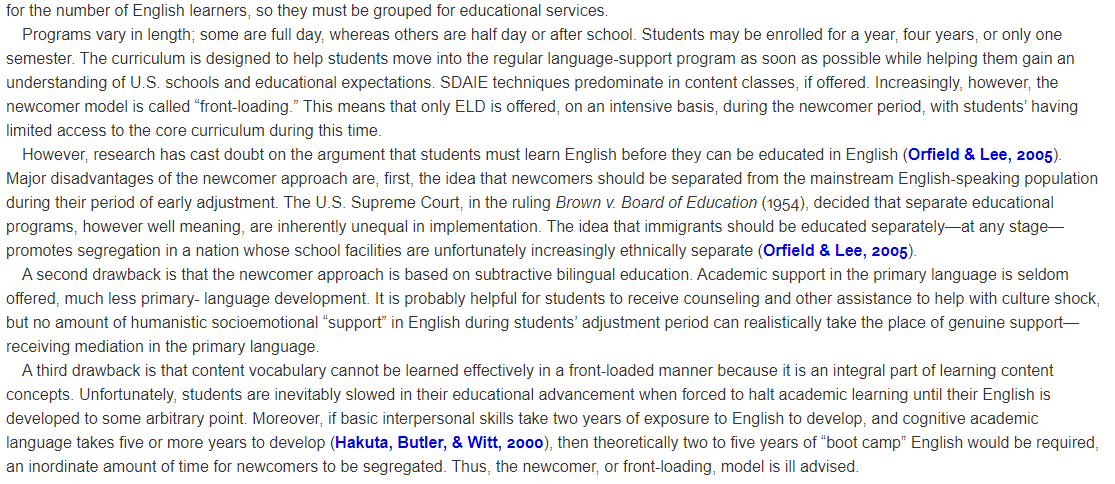

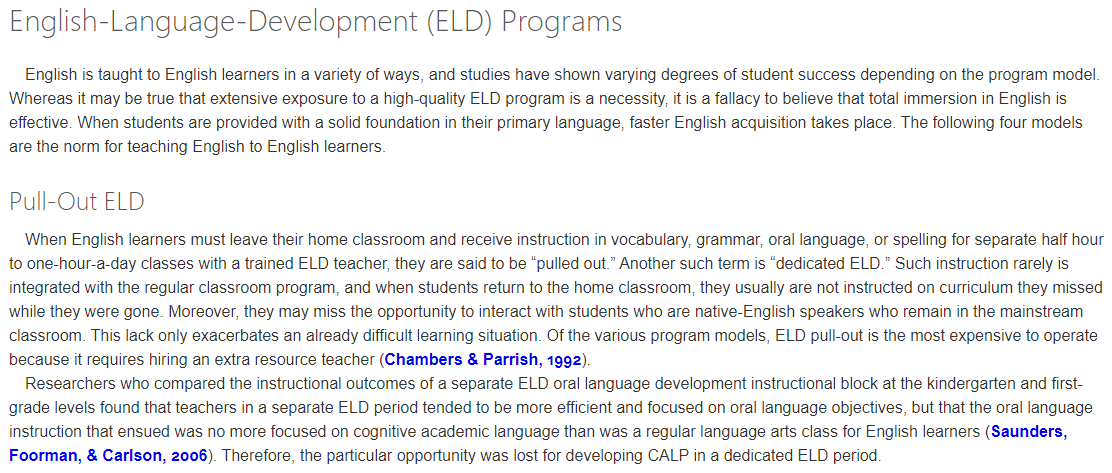

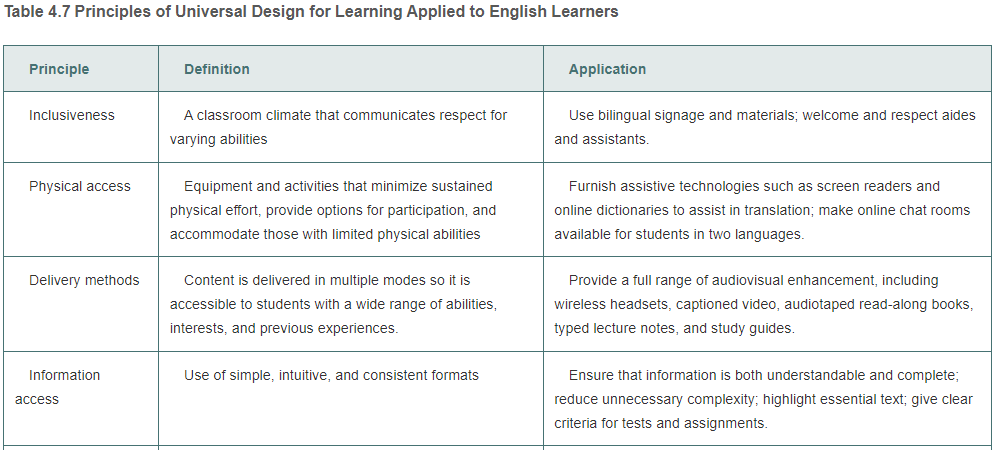

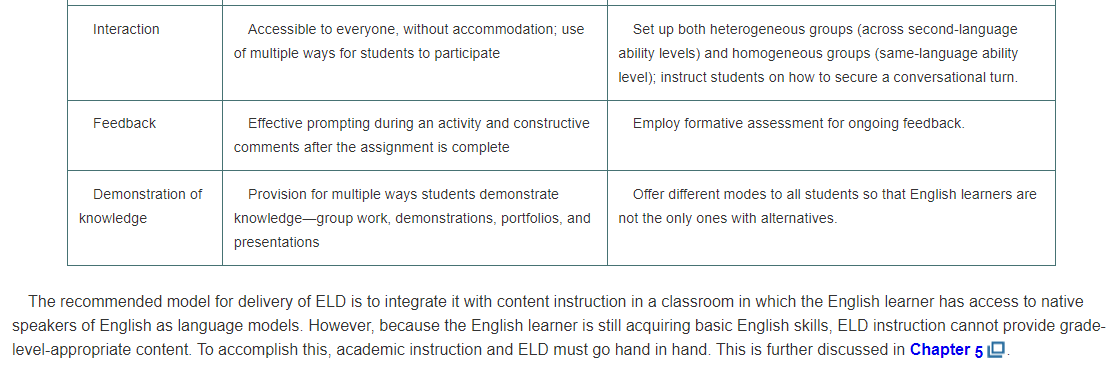

in a web- search engine, and access Ruiz Soto, Hooker, and Batalova (2015a). English learners comprise a growing proportion of school children in the United States. Weedezign/Shutterstock Spanish-Speaking English Learners The majority of households in the United States in which English is not spoken are Spanish-speaking (28.1 million). This may be because Latinos are the fastest-growing segment of the population, making up 17.8 percent of the U.S. population as of July 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). By 2060, Hispanics are projected to constitute 30.6 percent of the U.S. population, rivaling Whites at 42.6 percent (Ewert, 2015) (the terms Hispanic and Latino are used interchangeably in the census reports)-so Spanish will sustain its place as the largest home language of English learners in the United States. Of the Spanish-speaking households, 66.1 percent are from Mexico or of Mexican American origin; 14.5 percent are from Central or South America; 9 percent are from Puerto Rico or of Puerto Rican origin; 4 percent are from Cuba or of Cuban American origin; and 6.4 percent are from other Hispanic/Latino origin. Latinos make up about 30 percent of the population of New York City (West & Alfaro, 2017), 39 percent of the population of California (Panzar, 2014), 47 percent of New Mexico, 39 percent of Texas (Pew Research Center, 2014), and 24.9 percent of Florida (U.S. Census Bureau, 2017). In 2013, 71 percent of all Latinos were urban, and lived in one of the 100 largest counties of Hispanic population, especially those in California, Texas, and Florida (Brown & Lopez, 2013); more than 9 percent of all Hispanics in the United States live in Los Angeles County. Many Spanish speakers are poor-in 2015, 21.9 percent of all Latinos were living in poverty (Flores, Lpez, & Radford, 2017) (compared with 7.7 percent of non-Latino Whites). addition, of the 18.2 million Latino children under age eighteen (25 percent of the U.S. population of such children)-95 percent of whom are U.S.-born-62 percent lived in low-income families (Mather, 2016). Living in poverty increase the chance that such children face poor schools, health issues, and nutritional challenges, in addition to the need to learn English. Asian/Pacific English Learners The second largest non-English-speaking population comprises Asians and Pacific Islanders. In 2008, the Asian and Pacific Islander population in the United States numbered about 15 million, constituting 5 percent of the population (Asian Nation, 2010). Asian refers to those having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent, including Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. Pacific Islander refers to those having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific islands. Like Spanish speakers, the U.S. Asians (in 2017, 21 million, 6.5 percent of the U.S. population) and Pacific Islanders (in 2017, 1.5 million) once lived predominently in metropolitan areas (in 2001, nearly 96 percent) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). However, by 2012, almost half of this population had moved to the suburbs (Taxin, 2012). The Asian American population is growing faster than any other major ethnic or racial group: 42 percent of the 8.1 million people who came to the United States from a foreign country were from Asia in the years 2010-2016 (Learning English, 2017). In 2011, nearly 2.9 million people spoke some form of Chinese in the United States, whether Mandarin, Cantonese, or Formosan -the third-most spoken language in the United States (Florcruz, 2013). By and large, then, in the United States, those who educate English learners are more likely to find employment in the states of California, New Mexico, New York, or Texas, or in central city schools, serving Hispanics or Asian and Pacific Islanders. Aside from this employment likelihood, however, demographics indicate that services for English learners are needed in every state and large city. To educate English learners, resources are badly needed. However, many inner-city schools are faced with large numbers of poor children, fewer books and supplies, and teachers with less training and experience. Other English learners, particularly those Asians who live the suburbs, experience well- funded schools. Thus, excellence in education for English learners is frequently, but not always, compromised by the fact that some English learners may be poor and attending underfunded and poorly equipped schools. Putting Faces to Demographics English learners in the United States present a kaleidoscope of faces, languages, and cultures: Hayat, eleventh grade, refugee from Afghanistan, living in Oakland, California Rodica, eighth grade, adoptee from Romania, living in Kansas City, Missouri Viviana, third grade, second-generation Mexican American living in Prescott, Arizona, whose parents speak no English Hae Lim, second grade, visitor from Pusan, Korea, "temporarily" living with an aunt in Torrance, California Axlam, eleventh grade, attending high school in Lewistown, Maine, learning English in the hopes of soon enrolling in a local community college Lei Li, kindergartner, attending a neighborhood school in Amherst, Massachusetts, while her mother is an international student at a nearby university Tram, tenth grade, living in inner-city San Jos, whose parents speak Vietnamese but who has lived in the United States since he was two years old Augustn, fourth grade, a Trique Indian from San Juan Copala in the Oaxaca state in Mexico, who speaks Spanish as a second language and is learning English as a third language Juan Ramon, second grade, whose mother recently moved from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to live with relatives in Teaneck, New Jersey Some of these students may be offered primary-language instruction as a part of the school curriculum, but those students whose language is represented by few other students in the school district face structured English immersion, with little support in their native language. English Learners with Learning Challenges Some English learners face academic learning challenges in addition to the need to acquire a second language. They may be diagnosed with learning disabilities and referred to special education services; they may suffer culture shock during the process of acculturation; or they may experience other difficulties that require counseling services or situations in which their families are not able to meet their social, emotional, or health needs. Like their counterparts who are native-English speakers, English learners may require special services, including referral to gifted-and-talented programs, resource specialists, reading-resource programs, counseling, and/or tutoring. English Learners: An International Profile English is a fast-growing global language. In countries such as Canada, England, and Australia, immigrants study English as a second language, just as they do in the United States, making ESL a well-established curriculum in English-dominant countries. The term English learners also includes those studying English as a foreign language (EFL), usually as an academic subject in elementary, middle, or high schools-but also in private, proprietary institutes that cater to those who must learn English for business, scientific, or other career-related purposes. This division is not clean-cut, because English is widely used for international communication, especially with the Internet. English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) is also a widely used term; hence, Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) is the term for the profession. Other terms and their definitions are presented in Table 1.2 L Table 1.2 English-Learner-Related Terms Term Definition English as a foreign language (ESL) Classes for English learners who live in places where English is, by and by large, an academic subject, which functions narrowly in that culture as a tool for communicating with outsiders English as a second language (ESL) Classes for English learners who live in places where English has some sort of special status or public availability English language development (ELD) English language teaching or training (ELT) English learner (English-language learner, ELL) English-only (EO) ESOL services Language acquisition (includes language learning) Language minority Term used in the United States to refer to ESL services. Term used internationally to refer to EFL services. A student who is learning English as an additional language A term with two meanings: (1) a monolingual person in English; (2) a policy of English as the only national language of the United States English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes designed for students who want to improve their written and spoken English skills. Learning language in a natural context or formally through rules of grammar and usage A term used in internationally to denote language speakers who although may be a minority in their country. have, under international law, certain language rights Language minority A term used in internationally to denote language speakers who although may be a minority in their country. have, under international law, certain language rights Language other than English (LOTE) A term usually used to characterize the language of a student's home environment Target language (TL) The language that is being learned in ELD or ELT (may be American, Australian, British English, etc.) English learner who is ready for redesignation (mainstreaming) Fluent English proficient (FEP) or fluent English speaker (FES) English learner who is not yet ready for redesignation Limited English proficient (LEP), or limited English speaker (LES) Teaching English learners is a broad and flexible profession. ESOL educators can be found in Mandarin-English dual-language immersion kindergartens in Seattle, college classrooms in Tokyo, adult education classes in Florida, "cram" schools in Seoul, precollegiate preparation courses in Texas, middle school social studies classes in California, five-year vocational colleges in Taiwan, private schools in the United Arab Emirates, or in summer intensive programs in Uzbekistan-at a myriad of levels from preschool to postgraduate in a host of countries around the world. Teaching with Integrity This book takes a critical perspective on the education of English learners-one that looks at dual-language proficiency and language policy in the context of broader issues of social equity and social justice. Teachers who develop a deeper understanding of the effects of culture and language on the success or disenfranchisement-of CLD students through school culture, curricula, and instructional methods are better prepared to promote social change. Teachers with a critical perspective look within, around, and beyond educational issues; ask probing questions about the role of educators in the struggle to attain fairness, justice, equity, and equal opportunity in the world; and work toward social equity and justice as a part of their role as language educators. One of the major challenges for those who teach English learners is to motivate them to reach the highest possible level of school achievement. In this process, teachers work to create a classroom environment characterized by equal opportunity and a democratic process so that English learning represents a positive experience. A second challenge is to respect native languages and the rights of their speakers. Teachers who make sincere attempts to learn the languages of their students and build English on students' prior language expertise serve as intercultural and interlingual educators. Only in the context of full support for the bilingual, bicultural learner does the teaching of English respect the learner's linguistic and cultural heritage. Critical educators are those who teach with integrity (Balderrama & Daz-Rico, 2006). Their passion for teaching and learning fosters within their students the capacity for joyful lifelong learning, a feeling of respect for and pride in their own culture, and a sense of curiosity regarding human diversity. Colleagues can undertake together the task of achieving social justice: equal access to, and opportunity for, quality education for all students. Critical educators advocate an inclusive society in which language, literacy, and culture are integrated with respect and not compromised in any way. Teachers are intellectual workers, knowledge professionals with cultural expertise. As such, the role of teachers is to help students attain the wisdom and skills the whole community needs to prosper. Teachers of English learners provide academic content and English-language development while upholding high professional standards within an intellectually challenging context grounded in academic knowledge that is humane and ethical, upholding intercultural relationships and promoting educational equity. Teaching with integrity includes six elements. The Willingness to Be Fully Human First, teachers must be willing to be human and to treat others with humanity. This is partially fulfilled when the teacher deeply believes-and communicates the belief that teachers and students have equal civil rights in the classroom as well as parity as fellow human beings. One way of looking at the humanity of teaching is to examine the ways in which teachers and students mutually socialize one another in classroom interaction. When teachers communicate a sense of respect and share an enjoyment of shared cultural commonplaces, students are able to relax and feel more accepted and appreciated. This does not mean teachers act as "buddies" to students, but rather as fully actualized human beings who are able to apologize when wrong, seek peer help when unsure, and grow and learn alongside students. Teachers with integrity have compassion at their core because they are conscious of others' misfortunes and distress and have an active desire to alleviate such hardships. High Expectations for Students A second facet of teaching with integrity is having high academic expectations for students, a deep commitment to the idea that all students can achieve academic success. Teacher expectations operate as a cycle of teacher-student mutual perceptions: Teachers and students each form ideas about the other, which they communicate in their interactions, causing both to respond in positive or negative ways. Recognizing, addressing, and understanding these expectations and how they operate are therefore essential parts of examining the role of a teacher's integrity with English learners. Teachers must learn to avoid prejudgments and stereotypes so that such negativity does not produce a self-fulfilling prophecy of low achievement. Even if students have internalized low expectations for themselves, teachers who strive to change students' low academic prophecy of low achievement. Even if students have internalized low expectations for themselves, teachers who strive to change students' low academic performance can sow seeds of improved self-esteem. The strongest teachers are those who believe in students' success more than students believe in their own failure. Teachers with flexible expectations readily revise their impressions when direct information about student achievement is available. Being "Fully Qualified" A third aspect of teaching with integrity is expertise in content; teachers must be fully qualified in the areas they will instruct. Two areas of content expertise related specifically to English learners that are not often required-but should be are the following: (1) theories and pedagogy relevant to teaching English learners academic literacy; and (2) some degree of proficiency in the primary language of their students. Given the existing linguistic diversity prevalent in U.S. classrooms, these two areas of expertise are central to the implementation of content knowledge. The widely accepted mythology in the United States that a person can be well educated and remain monolingual is questionable with regard to being "fully qualified" as an educator. The Latino population has become the largest minority in the United States, and educators who are able to augment their teaching using both second-language acquisition principles and Spanish-language skills are increasingly needed. This political clarity is important if teachers are to act effectively and facilitate student empowerment. First and foremost, teachers can function as more conscientious professionals when they understand the larger social and political forces that affect their professional lives. With this understanding, teachers can confront these forces with the tools to change those aspects of society that undermine educational success, particularly for low-status student groups such as English learners. As suggested in the definition of political clarity, teachers must be cognizant that they do not teach in a vacuum, but that instead their work is interconnected with broader social processes that affect their teaching. Commonly accepted belief systems justify and rationalize the existing social order. How do teachers explain the fact that multilingualism is facilitated for the privileged but not encouraged for those students who come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds? The ideology of unexamined beliefs affects teaching and schooling practices at the level of microinteractions in daily classroom life. Social institutions such as schools play major roles in maintaining and perpetuating processes important to society. Certain groups manage to dominate others and determine how people in positions of privilege maintain those positions with the support and approval of the disempowered-a process Leistyna, Woodrum, and Sherblom (1996) define as hegemony, the unexamined acceptance of the social order-even when the social classes in power make decisions that disempower others. Beliefs about language are powerful hegemonic devices, intimately connected to social position. For example, beliefs about second-language acquisition in the United States privileges French above Spanish as a preferred foreign language of study and stigmatizes nonnative speakers of English through actions of English teachers that privilege native speakers. However, at every opportunity, teachers with integrity oppose attitudes based on hegemonic ideas or folk beliefs, upholding professional practices that are substantiated by research or infused with clarity of vision about the all-too-hidden processes Teaching with integrity means wholeness in all that teachers do. This implies a genuine vision of social justice in the classroom. Teachers with integrity are able to sustain their humanity in the face of potentially dehumanizing forces that would reduce teaching and learning to mechanical enterprises devoid of intrinsic interest and personal investment. As suggested earlier, teaching English learners is a challenging and complex task requiring both integrity in teaching and pedagogical skills and knowledge along various dimensions of instruction. Teaching with integrity provides a model for a professional approach that is humane, student-centered, and equitable. 4 Programs for English Learners Learning Outcomes After reading this chapter, you should be able to ... Recall major events in the support for bilingual competence in the United States; Survey federal and state requirements for bilingual education programs; Discuss major issues in the politics of bilingual education; Describe how education policies promote equity and empowerment for English learners; Explore the strengths and drawbacks of various types of programs for English learners; and Explain how school can sustain partnerships with families of English learners. English learners enter schooling fluent in a primary language other than English, a proficiency that can function as a resource. In many parts of the world, including Canada, second-language instruction is considered either a widely accepted component of being well educated or a legal mandate in an officially bilingual country. Acquiring a second language is not easy, especially to the level of using that language to succeed in postsecondary education. English learners face that challenge daily. A growing number of schools in the United States offer two-way immersion programs that help English learners develop academic competence in their heritage language while acquiring fluency and literacy in English-at the same time, native-English-speaking students develop speaking fluency and academic competence in the home language of the English learners. These programs showcase the idea that multicompetent language use (Cook, 1999, p. 190) is a valuable skill. Proficiency in multiple languages is also a career enhancement in the modern world of global commerce. The classrooms of the United States are increasingly diverse, with students coming from many countries of the world. The challenge to any English- language development (ELD) program is to cherish and preserve the rich cultural and linguistic heritage of the students as they acquire English. This chapter addresses the history, legality, and design of program models that induct speakers of other languages into English instruction. Although most of these programs take place at the elementary level, an increasing number of students immigrate to the United States at the middle and high school levels, and programs must be designed to meet their needs as well. The program models presented in this chapter vary greatly on one key dimension-how much encouragement is offered to students to maintain their primary language and how much instructional support they receive to accomplish this. The History of Multilingual Competency in the United States Bilingualism has existed in the United States since the colonial period, but over the more than two centuries of American history it has been alternately embraced and rejected. The immigrant languages and cultures in North America have enriched the lives of the people in American communities, yet periodic waves of language restrictionism have virtually eradicated the capacity of many U.S. residents to speak a foreign or second language, even those who are born into families with a heritage language other than English. For English learners, English-only schooling has often brought difficulties, cultural suppression, and discrimination even as English has been touted as the key to patriotism and success. This section traces the origin and development of, and support for, language services for English learners in the United States. Early Bilingualism in the United States At the time of the nation's founding, at least twenty languages could be heard in the American colonies, including Dutch, French, German, and numerous Native American languages. In 1664 at least eighteen colonial languages were spoken on Manhattan Island. Bilingualism was common among both the working and educated classes, and schools were established to preserve the linguistic heritage of new arrivals. The Continental Congress published many official documents in German and French as well as in English. German schools were operating as early as 1694 in Philadelphia, and by 1900 more than 4 percent of the U.S. elementary school population was receiving instruction either partially or exclusively in German. In 1847, Louisiana authorized instruction in French, English, or both at the request of parents. The Territory of New Mexico authorized Spanish-English bilingual education in 1850 (Crawford, 1999). Table 4.1 surveys the early history of language use and policy in America. Table 4.1 Early History of Language Use and Policy in America Date Event Significance Pre-1492 North America is rich in indigenous languages. Linguistic diversity is a type of biodiversity, encoding millennia of information about the physical and social environment. 16th century Spanish rulers decree the replacement of indigenous languages by Spanish. Spain establishes missions in what is now California. 1781 Early acknowledgment of U.S. multilingualism on the part of the Founding Fathers. U.S. Articles of Confederation are written in English, French, and German. 1800s Mexicans and Native Americans are excluded from Whites-only schools. European Americans settle Western U.S. 1828 The U.S. government recognizes the language rights of the Cherokee tribes. U.S. government signs a treaty with Cherokee tribes. 1839 Ohio adopts bilingual education. Schools could operate in German and English by parental request. 1848 Mexican territory is annexed to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Mexican residents of appropriated territory in what are now California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Utah, and Nevada are promised the right to use Spanish in schools, courts of law, employment, and everyday life. 1864 The federal government forces Native American children to attend off-reservation schools. Schools are English-only. Native Americans are punished for using their native language. 1888 Wisconsin and Illinois attempt to institute English-only schooling. First antibilingual education legislation is passed. 1898 U.S. wins Spanish-American War and colonizes Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Public and private schools are forced to use English as the language of instruction. Submersion in English is a sustained policy in Puerto Rican schools until the 1950s. Although there were several such pockets of acceptance for bilingual education, other areas of the country effectively restricted or even attempted to eradicate immigrant and minority languages. In 1879, the federal government forced Native American children to attend off-reservation, English-only schools where they were punished for using their native language. In the late nineteenth century, in the eastern United States, as large numbers of eastern Europeans immigrated, descendants of the English settlers began to harbor resentment against these newcomers. At the same time, new waves of Mexican and Asian immigration in the West brought renewed fear of non-English influences (Crawford, 1999). Best Practice Early Cherokee Language Rights Under an 1828 treaty, the U.S. government recognized the language rights of the Cherokee tribe. Eventually, the Cherokees established a twenty- one-school educational system that used the Cherokee syllabary to achieve a go percent literacy rate in the native language. About 350,000 Aniyunwiya (Cherokee) people currently live primarily in Oklahoma and North Carolina, and about 22,000 speak the language (which today is known as Tsalagi). (www.native-languages.org/cherokee.htm) The Struggles for Language Education Rights in the Twentieth Century World War I brought anti-German hysteria, and various states began to criminalize the use of German in all areas of public life. Subsequently, fifteen states legislated English as the basic language of instruction. This repressive policy continued during World War II, when Japanese-language schools were closed. Until the late 1960s, "Spanish detention"-being kept after school for using Spanish-remained a formal punishment in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, where using a language other than English as a medium of public instruction was a crime (Crawford, 1999). Although the U.S. Supreme Court, in the Meyer v. Nebraska case (1923), extended the protection of the Constitution to everyday speech and prohibited coercive language restriction on the part of states, the nativist backlash during and after World War I had fundamentally changed public attitudes toward learning in other languages. European immigrant groups felt strong pressures to assimilate, and bilingual instruction by the late 1930s was virtually eradicated throughout the United States. This assimilationist mentality worked best with northern European immigrants. For other language minorities, especially those with dark complexions, English-only schooling brought difficulties. Discrimination and cultural repression became associated with language repression. After World War II, writers began to speak of language-minority children as being "culturally deprived" and "linguistically disabled." The cultural deprivation theory pointed to such environmental factors as inadequate English-language skills, lower-class values, and parental failure to stress educational attainment. On the basis of their performance on IQ tests administered in English, a disproportionate number of English learners ended up in special classes for the educationally handicapped. Bilingual education was reborn in the early 1960s in Dade County, Florida, as Cuban immigrants, fleeing the 1959 revolution, requested bilingual schooling for their children. The first program at the Coral Way Elementary School was open to both English and Spanish speakers. The objective was fluency and literacy in both languages. Subsequent evaluations of this bilingual program showed success both for English-speaking students in English and for Spanish-speaking students in Spanish and English. Hakuta (1986) reported that by 1974 there were 3,683 students in bilingual programs in the elementary schools nationwide and approximately 2,000 in the secondary schools. Legal and Legislative Mandates Supporting Language Education Rights Progress in ELD services in the United States has taken place on three fronts: cultural, legislative, and judicial. Culturally, the people of the United States have seemed to accept bilingualism when it has been economically useful and to reject it when immigrants were seen as a threat. Legislative and judicial mandates have reflected this ambivalence. After the civil rights era, the provision of services for English learners has been viewed as a right. This is consonant with the Universal Declaration of Linguistic Rights signed in Barcelona in June 1996, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National, Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities of the General Assembly of the United Nations (1992). Lau v. Nichols In 1973 a group of non-English-speaking Chinese families sued San Francisco Unified School District officials, claiming that "sink or swim" instruction (denial of language development services) was a violation of students civil rights under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Lower federal courts had absolved the school district of any responsibility for minority children's "language deficiency." But a unanimous Supreme Court ruled as follows: "There is no equality of treatment merely by providing students with the same facilities, textbooks, teachers, and curriculum, for students who do not understand English are effectively foreclosed from any meaningful education"-essentially stating that imposing the requirement that a child must have basic skills in English before effectively participating in the educational program is "to make a mockery of public education" (414 U.S. 563). Although Lau v. Nichols did not specify what type of program a school district must offer, the Chinese parents who sued the San Francisco Unified School District formed an advisory committee, and eventually a program emerged that satisfied the requirements set forth by the court. In 1975, the May 25 Memorandum from the Office for Civil Rights (also called the Lau Remedies) mandated that school districts with more than 5 percent national-origin minority children must offer special language instruction for students with a limited command of English. To be in compliance with Lau v. Nichols, the Lau Remedies are still used as the required elements in most states. They prohibit the assignment of students to classes for the handicapped on the basis of their English-language skills, disallow placing such students in vocational tracks instead of teaching them English, and mandate that administrators communicate with parents in a language they can understand. Because the states reserve the right to dictate educational policy, services for English learners have depended on the vagaries of state law. When the U.S. Congress enacted legislation to begin Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, federal funding became available for bilingual education programs. Almost simultaneously, the courts began to rule that students deprived of bilingual education must receive compensatory services. Together, the historical precedents, federal legislative initiatives, and judicial fiats combined to establish bilingual education in the United States (see Tables 4.2 and 4.3). Table 4.2 The Early Twentieth Century: Language Use and Policy Are Contested in the United States Date Event Significance 1906 First national English-language requirement Congress passes English requirement for naturalized citizenship. 1917- The governor of lowa bans the use of any foreign language in public. Ohio passes legislation to remove all uses of German from the state's elementary schools. With German speakers as the target, mobs raid schools and burn German textbooks. Subsequently, fifteen states legislate English as the basic language of instruction. French is forbidden to be spoken in schools in Maine. Ku Klux Klan members in Maine, numbering 150,141 in 1925, burn crosses in hostility to French Americans. Meyer v. Nebraska The Supreme Court bans an English-only law in a case brought by German Americans. Del Rio Independent School District v. Salvatierra A Texas superior court finds that the Del Rio Independent school district cannot segregate Mexican students, but a higher court rules that the segregation is necessary to teach English to Mexican students. 1918 1920s- 1970s 1923 1930 1931 1936 1941 1946. 1947 1961 1968 Lemon Grove v. lvarez Massive IQ testing of Puerto Ricans in New York is used to justify widespread school placement of Spanish- speaking children two to three years below grade level. Japanese-language schools are closed. Mndez v. Westminster School District Immigrants fleeing the Cuban revolution demand Spanish-language schooling. 10,000 Chicanos boycott schools in Los Angeles demanding bilingual education and more Latino teachers; boycotts spread across U.S. A state superior court rules that school segregation is against the law in California. Thousands of New York Puerto Ricans launch a campaign for bilingual education. Japanese are incarcerated in internment camps with English-only schools. The U.S. Ninth District Court applies the 14th Amendment to schools, insisting "schools must be open to all children... regardless of lineage." Dade County, Florida, implements Spanish-English bilingual education. Leaders of Los Angeles boycott are arrested; two years later charges against them are declared unconstitutional. Table 4.3 Key Legislation and Court Cases in the Struggle for English Learners' Language Rights Date Event Significance 1964 The Civil Rights Act: Title VI Prohibits denial of equal access to education on the basis of race, color, national origin, or limited proficiency in English in the operation of a federally assisted program. Compliance is enforced through the U.S. Office for Civil Rights. 1968 First bilingual kindergarten in New York City; first bilingual education major at Brooklyn College. ESEA Title VII offers funding for bilingual education programs. Early 1970s Based on these data, the U.S. Office of Civil Rights begins enforcing compliance with judicial mandates. Bilingual programs reach only one out of every forty Mexican American students in the Southwest. 1972 Serna v. Portales Municipal The first federal court enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. A federal judge orders instruction in native language and culture as part of a desegregation plan. Schools 1973 1974 1974 1975 1977 Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colorado The Equal Education Opportunities Act (EEOA) (U.S. Congress) Lau v. Nichols Lau Remedies-guidelines from the U.S. Commissioner of Education Ros v. Read Latinos must be covered by Brown v. Board of Education-Mexicans cannot be labeled "White" and used to create falsely desegregated schools containing only Blacks and Latinos. "No state shall deny equal educational opportunities to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex, or national origin by the failure of an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in its instructional programs." U.S. Supreme Court establishes the right of students to differential treatment based on their language minority status, but it does not specify a particular instructional approach. Standardized requirements for identification, testing, and placement into bilingual programs. Districts are told how to identify and evaluate children with limited English skills, what instructional treatments to use, when to transfer children to all-English classrooms, and what professional standards teachers need to meet. A federal court rules that a bilingual program must include a cultural component. 1977 1981 1982 1987 1990 Ros v. Read Castaeda v. Pickard Plyler v. Doe Gmez v. Illinois State Board of Education Florida Consent Decree A federal court rules that a bilingual program must include a cultural component. The Fifth Circuit Court tests the 1974 EEOA statute, outlining three criteria for programs serving EL students. District programs must be: (1) based on "sound educational theory," (2) "implemented effectively" through adequately trained personnel and sufficient resources, and (3) evaluated as effective in overcoming language barriers. Qualified bilingual teachers must be employed, and children are not to be placed on the basis of English-language achievement tests. The U.S. Supreme Court decides that a state's statute that denies school enrollment to children of illegal immigrants "violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment." State school boards can enforce state and federal compliance with EEOA regulations. Districts must properly serve students who are limited in English. A federal district court can mandate and monitor statewide teacher preparation and school districts' English learner education. 1994 1998 2001 2004 2004 California passes Proposition 187, which makes it illegal to provide public education to illegal immigrants. California voters approve Unz Initiative Proposition 227 (ED Code 300-340). No Child Left Behind Act, Title III Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (IDEA), Public Law 108-446 Williams et al. v. State of California et al. Proposition is overturned in the courts because it violates Plyler v. Doe. Requires that K-12 instruction be overwhelmingly in English, restricting use of primary language as a means of instruction. Subsequent measures pass in Arizona and Massachusetts, but French speakers vote down similar initiative in Maine. Federal funding is available to support schools in educating English learners. Congress aligns education of children with disabilities with NCLB to mandate equity and accountability. California schools must provide equitable access to textbooks, facilities, and teaching staffs, including teachers of English learners. Did You Know? Indigenous Language Rights Times have changed for Native American language speakers. In the United States, in 2010 there were 372,095 residents who spoke one of 169 native North American languages (Siebens & Julian, 2011). The most-spoken Native American language was Navajo, with 169,471 speakers. In 1990, the U.S. Congress passed Public Law 101-477, which sustains the right of Native Americans to express themselves through the use of Native American languages in any public proceeding, including publicly supported education programs. Among the goals of this law are the following: Preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedom of Native Americans to use, practice, and develop Native American languages Increase student success and performance Promote students' awareness and knowledge of their culture and history Enhance student and community pride Federal and State Requirements for ELD Services Successive authorizations of the federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1968, 1974, 1978, 1988, and 1989 incorporated federal recognition of the unique educational disadvantages faced by non-English-speaking students. In 1968, Congress authorized $7.5 million to finance seventy-six bilingual education projects serving 27,000 children. In 1974, Congress specifically linked equal educational opportunity to bilingual education, allowing Native American and English-speaking children to enroll in bilingual education programs, and funding programs for teacher training, technical assistance for program development, and development and dissemination of instructional materials. In 1978, Congress added to the definition of bilingual education, stipulating that instruction in English should "allow a child to achieve competence in the English language." Additionally, parents were included in program planning, and personnel in bilingual programs were to be proficient in the language of instruction and English. In 1988, Congress increased funding to state education agencies, placed a three-year limit on participation in transitional bilingual programs, and created fellowship programs for professional training. Developmental bilingual programs were expanded to maintain the native language of students in the reauthorization of 1989. When the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965 was amended and reauthorized in 1994, it was within the framework of Goals 2000, with the goal to "educate limited-English-proficient children and youth to meet the same rigorous standards for academic achievement expected of all children and youth" ([7102][b]). This emphasis on standards was the linchpin of the 2001 reauthorization, the No Child Left Behind Act, in which all schools were required to provide qualified teachers, and all students were required to pass standardized tests. Every Student Succeeds Act Under the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), a reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary School Act, states are required to provide assurance that they had adopted academic content standards in three areas: reading, mathematics, and science. Annual testing in reading and mathematics is required for all students from third to eighth grade and once in high school. Other mandates are that schools continue to report student achievement by subgroups and issue an annual state report card, among other data. Unlike measure under No Child Left Behind, the previous ESEA authorization, states are free to determine what consequences, if any, should result from the failure to measure up to required standards (Dufour, 2016). The Florida Consent Decree In 1990, a broad coalition of civil rights organizations involved in educational issues signed a consent decree giving the United States District Court, Southern District of Florida, the power to enforce an agreement with the Florida State Board of Education regarding the identification and provision of services to students whose native language is other than English. This remains the most extensive set of state mandates for the education of English learners. The consent decree settlement terms mandate that six issues be addressed: Identification and assessment. National origin data of all students must be collected and retained in school districts, which must also form committees to oversee the assessment, placement, and reclassification of English learners. Equal access to appropriate programming. School districts must provide equal education opportunities for academic advancement and language support to English learners, including provisos for enhancing cross-cultural understanding and self-esteem. Equal access to appropriate categorical and other programming for limited-English-proficient (LEP) students. Schools must provide programs for compensatory education, exceptional students, dropout prevention, student service, prekindergarten, immigrant students, Chapter 10, pre-first-grade classes, home-school, and discipline. Personnel. Teachers must have various levels of English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) endorsement. Monitoring. Procedures must be followed by the Florida Department of Education to determine the extent to which school districts comply with the requirements of the agreement. Outcome measures. Mechanisms must be instituted to assess whether studen