Question: What operational changes would you recommend to Wally to improve performance? Wally Meyer deftly balanced his office keys and a large printout of forecasting data

What operational changes would you recommend to Wally to improve performance?

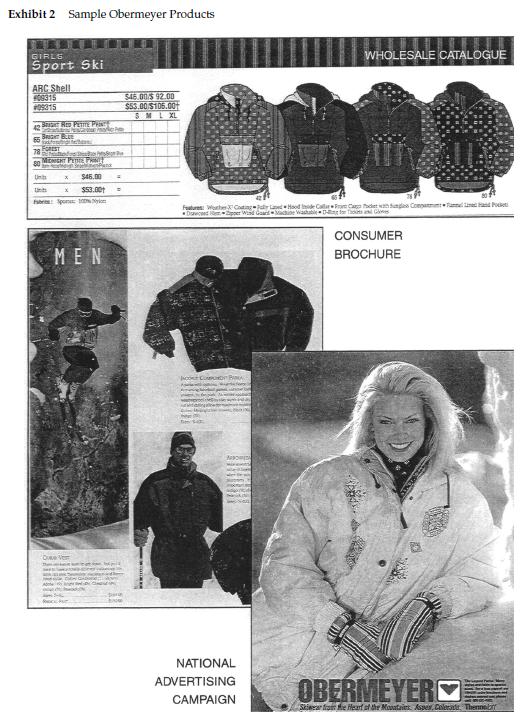

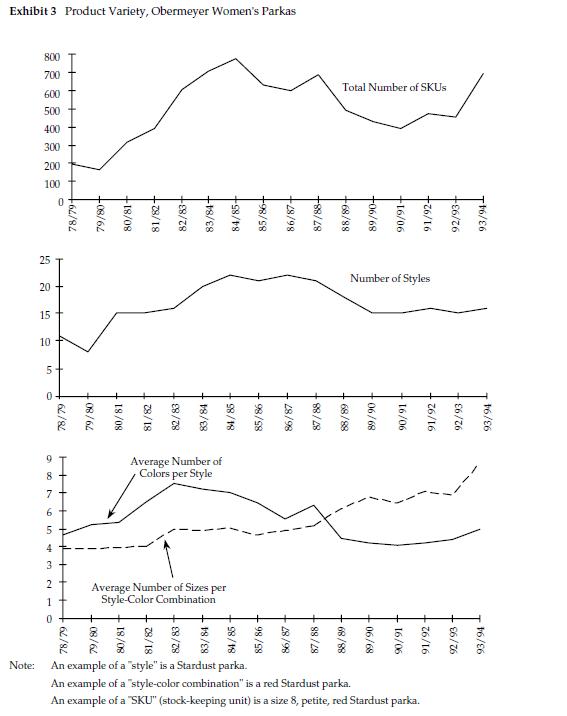

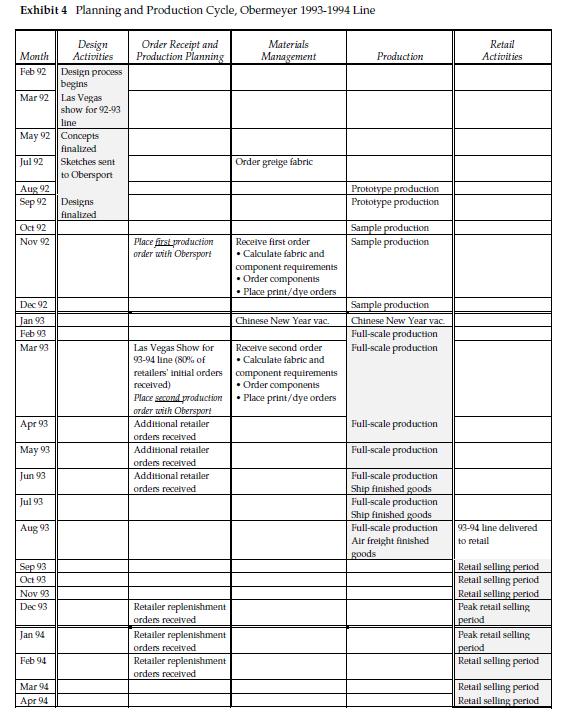

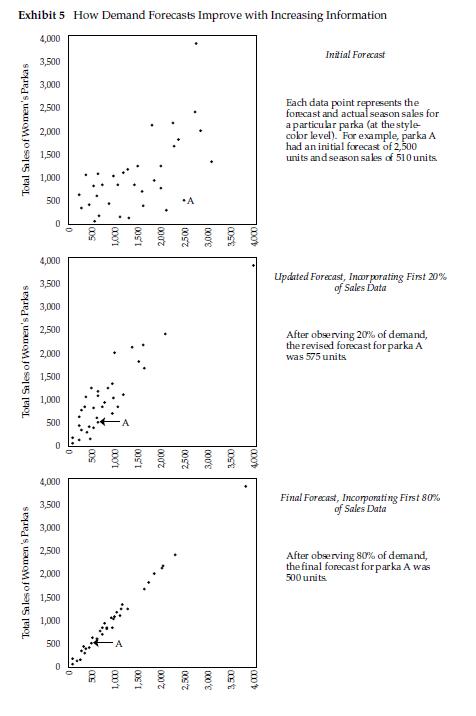

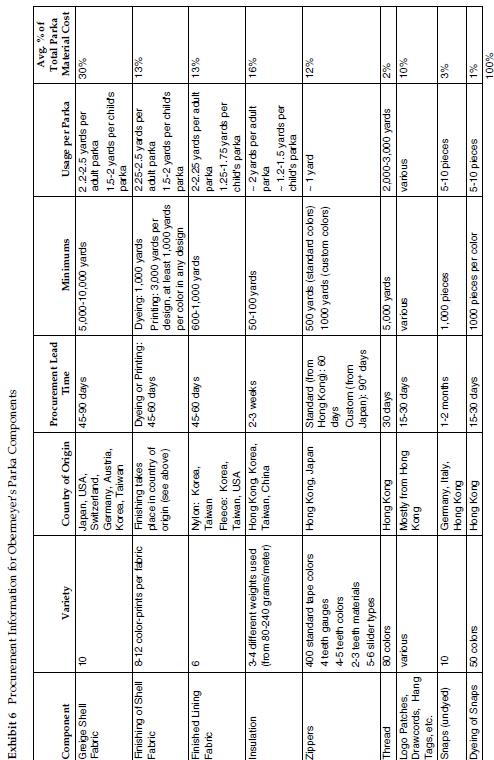

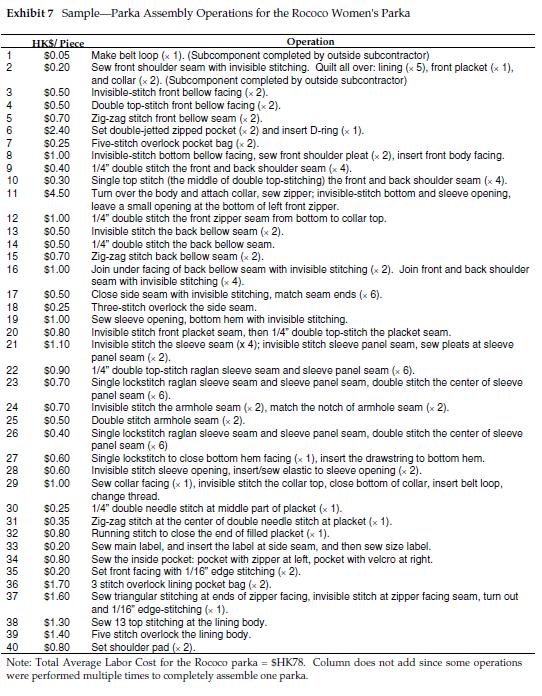

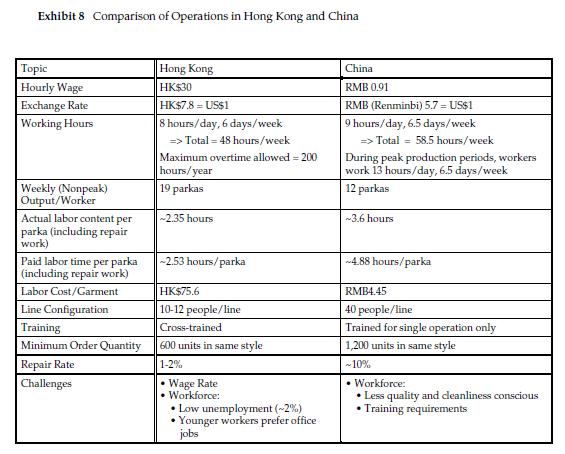

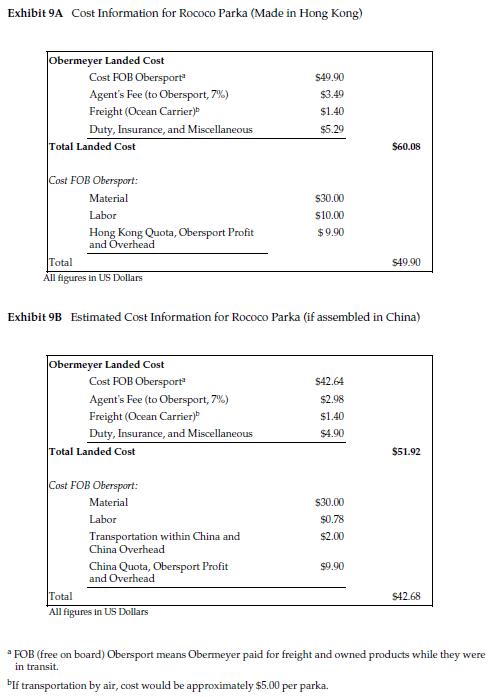

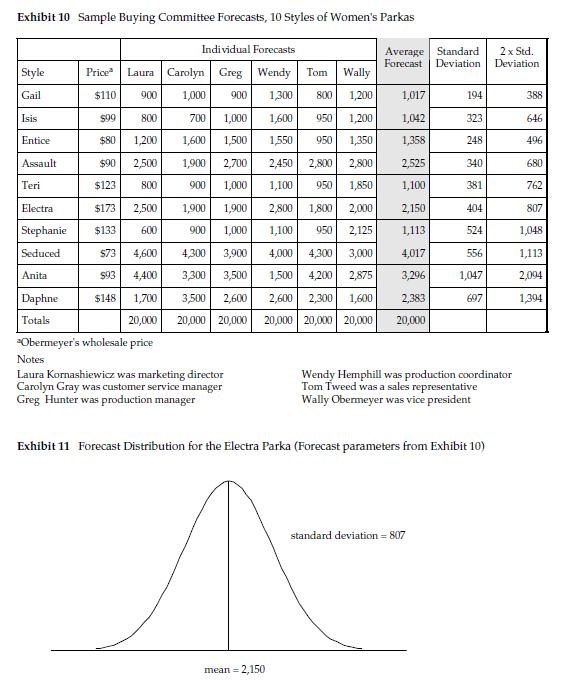

Wally Meyer deftly balanced his office keys and a large printout of forecasting data as he wheeled his mountain bike through the front entrance of Sport Meyer's headquarters in Aspen, Colorado. It was a crisp November morning in 1992; Wally paused for just a moment to savor the fresh air and beauty of the surrounding mountains before closing the door behind him. Wally had arrived at work early to start one of the most critical tasks Sport Meyer, a fashion skiwear manufacturer, faced each year—committing to specific production quantities for each skiwear item the company would offer in the coming year's line. The task required carefully blending analysis, experience, intuition, and sheer speculation: this morning Sport Meyer would start to make firm commitments for producing its 1993-1994 line of fashion skiwear with scant information about how the market would react to the line. In fact, no clear indications had yet emerged about how end-consumers were responding to the company's current 1992-1993 line. Despite the attraction of waiting for market information, Wally knew that further procrastination would delay delivery to retailers and that late delivery would reduce the exposure consumers would have to Meyer products. As usual, Meyer's new line offered strong designs, but the ultimate success of the line was highly dependent on how well the company was able to predict market response to different styles and colors. Feedback from retailers on the 1993-1994 line wouldn't begin to surface until the Las Vegas trade show next March, long after many of Meyer's products had entered production. Wally mused: How appropriate that our fate is always determined in Las Vegas. Like most fashion apparel manufacturers, we face a "fashion gamble" each year. Every fall we start manufacturing well in advance of the selling season, knowing full well that market trends may change in the meantime. Good gamblers calculate the odds before putting their money down. Similarly, whether we win or lose the fashion gamble on a particular ski parka depends on how accurately we predict each parka's salability. Inaccurate forecasts of retailer demand had become a growing problem at Meyer: in recent years’ greater product variety and more intense competition had made accurate predictions increasingly difficult. Two scenarios resulted—both painful. On one hand, at the end of each season, the company was saddled with excess merchandise for those styles and colors that retailers had not purchased; styles with the worst selling records were sold at deep discounts, often well below their manufactured cost. On the other hand, the company frequently ran out of its most popular items; although popular products were clearly desirable, considerable income was lost each year because of the company's inability to predict which products would become best-sellers. Wally sat down at his desk and reflected on the results of the day-long "Buying Committee" meeting he had organized the previous day. This year Wally had changed the company's usual practice of having the committee, which comprised six key Meyer managers, make production commitments based on the group's consensus. Instead, hoping to gather more complete information, he had asked each member independently to forecast retailer demand for each Meyer product. Now it was up to him to make use of the forecasts generated by the individuals in the group. He winced as he noted the discrepancies across different committee members' forecasts. How could he best use the results of yesterday's efforts to make appropriate production commitments for the coming year's line? A second issue Wally faced was how to allocate production between factories in Hong Kong and China. Last year, almost a third of Meyer's parkas had been made in China, all by independent subcontractors in Shenzhuen. This year, the company planned to produce half of its parkas in China, continuing production by subcontractors and starting production in a new plant in Lo Village, Guangdong. Labor costs in China were extremely low, yet Wally had some concerns about the quality and reliability of Chinese operations. He also knew that plants in China typically required larger minimum order quantities than those in Hong Kong and were subject to stringent quota restrictions by the U.S. government. How should he incorporate all of these differences into a well- founded decision about where to source each product? Tsuen Wan, New Territories, Hong Kong Raymond Tse, managing director, Meyersport Limited, was anxiously awaiting Sport Meyer's orders for the 1993-1994 line. Once the orders arrived, he would have to translate them quickly into requirements for specific components and then place appropriate component orders with vendors. Any delay would cause problems: increased pressure on his relationships with vendors, overtime at his or his subcontractors' factories, or even late delivery to Sport Meyer. Meyerssport Ltd. was a joint venture established in 1985 by Klaus Meyer and Raymond Tse to coordinate production of Sport Meyer products in the Far East (see Exhibit 1).Mysersport was responsible for fabric and component sourcing for Sport Meyer's production. Materials sourced were cut and sewn either in Raymond Tse's own "Alpine" factories or in independent subcontractors located in Hong Kong, Macau, and China. Raymond was owner and president of Alpine Ltd., which included skiwear manufacturing plants in Hong Kong as well as a recently established facility in China. Sport Meyer's orders represented about 80% of Alpine's annual production volume. Lo Village, Guangdong, China Raymond Tse and his cousin, Shiu Chuen Tse, gazed with pride and delight at the recently completed factory complex. Located amongst a wide expanse of rice paddies at the perimeter of Lo Village, the facility would eventually provide jobs, housing, and recreational facilities for more than 300 workers. This facility was Alpine's first direct investment in manufacturing capacity in China. Shiu Chuen had lived in Lo village all of his life—the Tse family had resided there for generations. Raymond's parents, former landowners in the village, had moved to Hong Kong before Raymond was born, returning to the village for several years when Raymond was a young boy during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in World War II. In 1991, Raymond Tse had visited Lo Village for the first time in over 40 years. The villagers were delighted to see him. In addition to their personal joy at seeing Raymond, they hoped to convince him to bring some of his wealth and managerial talent to Lo Village. After discussions with people in the community, Raymond decided to build the factory, so far investing over US$1 million in the facility. Working with Alpine's Hong Kong management, Shiu Chuen had hired 200 workers for the factory's first full year of operation. The workers had come from the local community as well as distant towns in neighboring provinces; most had now arrived and were in training in the plant. Shiu Chuen hoped he had planned appropriately for the orders Alpine's customers would assign to the plant this year; planning had been challenging since demand, worker skill levels, and productivity levels were all difficult to predict. Sport Meyer's origins traced to 1947, when Klaus Meyer emigrated from Germany to the United States and started teaching at the Aspen Ski School. On frigid, snowy days Klaus found many of his students cold and miserable due to the impractical clothing they wore—garments both less protective and less stylish than the clothing skiers wore in his native Germany. During summer months, Klaus began to travel to Germany to find durable, high-performance ski clothing and equipment for his students. An engineer by training, Klaus also designed and introduced a variety of skiwear and ski equipment products; for example, he was credited with making the first goose-down vest out of an old down comforter in the 1950s. In the early 1980s, he popularized the "ski brake," a simple device replacing cumbersome "run-away straps"; the brake kept skis that had fallen off skiers from plunging down the slopes. Over the years, Sport Meyer developed into a preeminent competitor in the U.S. skiwear market: estimated sales in 1992 were $32.8 million. The company held a commanding 45% share of the children's skiwear market and 11% share of the adult skiwear market. Columbia Sportswear was a lower-price, high-volume-per-style competitor whose sales had increased rapidly during the previous three years. By 1992 Columbia had captured about 23% of the adult ski-jacket market. Meyer offered a broad line of fashion ski apparel, including parkas, vests, ski suits, shells, ski pants, sweaters, turtlenecks, and accessories (see examples in Exhibit 2). Parkas were considered the most critical design component of a collection; the other garments were fashioned to match the parkas' style and color. Meyer products were offered in five different "genders": men's, women's, boys', girls', and preschoolers'. The company segmented each "gender" market according to price, type of skier, and how "fashion-forward" the market was. For example, the company divided its adult male customers into four types, dubbed Fred, Rex, Biege, and Klausie. A "Fred" was the most conservative of the four types; Freds had a tendency to buy basic styles and colors and were likely to wear the same outfit over multiple seasons. "High-tech" Rex was an affluent, image-conscious skier who liked to sport the latest technologies in fabrics, features, and ski equipment. In contrast, "Biege" was a hard-core mountaineering-type skier who placed technical performance above all else and shunned any nonfunctional design elements. A "Klausie" was a flamboyant, high-profile skier or snowboarder who wore the latest styles, often in bright colors such as neon pink or lime green. Within each "gender," numerous styles were offered, each in several colors and a range of sizes. Exhibit 3 shows how the variety of Meyer's women's parkas had changed over time, including the total number of stock-keeping units (SKUs) Meyer offered during the preceding 16-year period, as well as the average number of styles, colors per style, and sizes per style-color combination offered. Meyer competed by offering an excellent price/value relationship, where value was defined as both functionality and style, and targeted the middle to high end of the skiwear market. Unlike some of its competitors who made outerwear for both skiing and for casual "street wear," Meyer sold the vast majority (over 85%) of its products to customers for use while skiing. Functionality was critical to the serious skier—products had to be warm and water-proof, yet not constrain the skier's ability to move his or her arms and legs freely. Management believed that the effective implementation of its product strategy relied on several logistics-related activities, including delivering matching collections of products to retailers at the same time (to allow consumers to view and purchase coordinated items at the same time), and delivering products to retail stores early in the selling season (to maximize the number of "square- footage days" products were available at retail). Management Approach Throughout the company's history, Klaus Meyer had been actively involved in company management. Klaus believed that a company should run "free of tension." Klaus's personal philosophy was at the core of his management style; in both his personal life and his professional life he sought to "achieve harmony." He observed: We're blending with the forces of the market rather than opposing them. This leads to conflict resolution. If you oppose a force, you get conflict escalation. It is not money, it is not possessions, it is not market share. It is to be at peace with your surroundings. In accordance with his philosophy, Klaus believed that the skiwear industry should be left to people who were "comfortable with an uncertain bottom line." Klaus's management style emphasized trust in people and providing value to customers. He believed many aspects of the business fell into the artistic realm; in making decisions, one should be guided by one's judgment and intuition. In his joint venture with Raymond Tse, Klaus relied on his trust of Raymond and had always left production and investment decisions to Raymond. Although Klaus was the "heart and soul" of the company, other members of the family had played key roles in the company's growth as well. Klaus's wife, Nome, a successful designer, was actively involved in developing new products for the company. In Klaus's judgment, Nome had a "feel" for fashion—Klaus had relied heavily on her judgment in assessing the relative popularity of various designs. In recent years, Klaus's son Wally had become actively involved in managing the company's internal operations. After completing high school, Wally combined working part-time for the company with ski-patrolling on Aspen Mountain for six years before entering college in 1980. After graduating from the Harvard Business School in 1986, Wally initially focused his efforts on developing a hydro-electric power-generating plant in Colorado. By 1989, when the power plant was established and required less day-to-day involvement, Wally joined Sport Meyer full time as vice president. As is often the case, the company founder and his MBA son had different management approaches; Wally relied more heavily on formal data gathering and analytical techniques, whereas Klaus took a more intuitive style that was heavily informed by his extensive industry experience. Sport Meyer sold its products primarily through specialty ski-retail stores, located either in urban areas or near ski resorts. Meyer also served a few large department stores (including Nordstrom) and direct mail retailers (including REI). In the U.S., most retail sales of skiwear occurred between September and January, with peak sales occurring in December and January. Most retailers requested full delivery of their orders prior to the start of the retail season; Sport Meyer attempted to deliver coordinated collections of its merchandise into retail stores by early September. Nearly two years of planning and production activity took place prior to the actual sale of products to consumers (see Exhibit 4). The Design Process The design process for the 1993-1994 line began in February 1992, when Meyer's design team and senior management attended the annual international outdoors wear show in Munich, Germany, to view current European offerings. "Europe is more fashion-forward than the U.S.," Klaus noted. "Current European styles are often good indicators of future American fashions." In addition, each year, a major trade show for ski equipment and apparel was held in Las Vegas. The March 1992 Las Vegas show had provided additional input to the design process for the 1993-1994 line. By May 1992, the design concepts were finalized; sketches were sent to Meyersport for prototype production in July. Prototypes were usually made from leftover fabric from the previous year since the prototype garments were used only internally by Meyer management for decision-making purposes. Meyer refined the designs based on the prototypes and finalized designs by September 1992. Sample Production As soon as designs were finalized, Meyersport began production of sample garments—small quantities of each style-color combination for the sales force to show to retailers. In contrast to prototypes, samples were made with the actual fabric to be used for final production; dyeing and printing subcontractors were willing to process small material batches for sample-making purposes. Sales representatives started to show samples to retailers during the week-long Las Vegas show, typically held in March, and then took them to retail sites throughout the rest of the spring. Raw Material Sourcing and Production Concurrent with sample production, Meyersport determined fabric and component requirements for Meyer's initial production order (typically about half of Meyer's annual production) based on Meyer's bills of material. It was important that Meyersport place dyeing/printing instructions and component orders quickly since some suppliers' lead times were as long as 90 days. Cutting and sewing of Meyer's first production order would begin in February 1993. Retailer Ordering Process During the Las Vegas trade show, most retailers placed their orders; Meyer usually received orders representing 80% of its annual volume by the week following the Las Vegas show. With this information in hand, Meyer could forecast its total demand with great accuracy (see Exhibit 5). After completing its forecast, Meyer placed its second and final production order. The remainder of retailers' regular (non-replenishment) orders were received in April and May. As noted below, retailers also placed replenishment orders for popular items during the peak retail sales season. Shipment to Meyer Warehouse During June and July, Meyer garments were transported by ship from Myersport's Hong Kong warehouse to Seattle, from which they were trucked to Meyer's Denver distribution center. (Total shipment time was approximately six weeks.) Most goods produced in August were air- shipped to Denver to ensure timely delivery to retailers. In addition, for goods manufactured in China, air freighting was often essential due to strict quota restrictions in certain product categories. The U.S. government limited the number of units that could be imported from China into the United States. Government officials at the U.S. port of entry reviewed imports; products violating quota restrictions were sent back to the country of origin. Since quota restrictions were imposed on the total amount of a product category all companies imported from China, individual companies often rushed to get their products into the country before other firms had "used up" the available quota. Shipment to Retail; Retail Replenishment Orders Toward the end of August, Meyer shipped orders to retailers via small-package carriers such as UPS. Retail sales built gradually during September, October, and November, peaking in December and January. By December or January, retailers who identified items of which they expected to sell more than they currently had in stock often requested replenishment of those items from Meyer. This demand was filled if Meyer had the item in stock. By February Meyer started to offer replenishment items to retailers at a discount. Similarly, retailers started marking down prices on remaining stock in an attempt to clear their shelves by the end of the season. As the season progressed, retailers offered deeper discounts; items remaining at the end of the season were held over to the following year and sold at a loss. Meyer used a variety of methods to liquidate inventory at year-end, including selling large shipping containers of garments well below manufacturing cost to markets in South America and engaging in barter trade (for example, trading parkas in lieu of money for products or services used by the company, such as hotel rooms or air flights). The Supply Chain Apparel Manufacturers Meyer sourced most of its outerwear products through Meyersport. In recent years, Wally had worked with Metersport to "pre-position" (purchase prior to the season and hold in inventory) greige fabric as part of a wider effort to cope with manufacturing lead times. To pre-position the fabric, Meyer would contract with fabric suppliers to manufacture a specified amount of fabric of a given type each month; Meyer would later specify how it wanted the fabric to be dyed and/or printed. Meyer had to take possession of all fabric it contracted for, whether or not it was actually needed. Different types of fabrics were purchased for use as shell (outer) fabric and lining fabric. Approximately 10 types of shell fabrics were required each year. Meyersport purchased shell fabric from vendors in the United States, Japan, Korea, Germany, Austria, Taiwan, and Switzerland. Lining fabric was sourced primarily from Korea and Taiwan. (Exhibit 6 provides information on lead times, variety, and other aspects of component sourcing.) Each greige fabric would later be dyed and/or printed as necessary; each shell fabric was typically offered in 8 to 12 colors and prints. Prior to the start of the season, Meyersport would work with its subcontractors to prepare a small batch for each color that was required in a given fabric. The preparation of each such "lab-dip" took two weeks; the procedure at times had to be repeated if the quality of the lab-dip was not found to be satisfactory by Meyer managers or designers. In addition, Myersport worked with its printing subcontractors to develop "screens" which would be used to print patterns on fabric. This procedure took six weeks. Most other tasks were performed only after the production quantities planned by Sport Meyer were known. Immediately after receiving production instructions from Sport Meyer, Meyersport asked subcontractors to dye or print fabric. A typical adult's parka, for example, required 2.25 to 2.5 yards of 60" width shell fabric. The consumption of fabric was slightly less for kids' or preschoolers' parkas. Dyeing subcontractors required a lead time of 45-60 days and a minimum order quantity of 1,000 yards. Printing subcontractors required a minimum of 3,000 yards; printing lead times were also 45-60 days. Meyer products used insulation materials and a variety of other components in addition to shell and lining fabric. Each parka, for example, needed around 2 yards of insulation material. Insulation materials (with the exception of goose-down insulation, which was purchased in China and Korea) were purchased from DuPont, whose licensees in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Korea and China could provide them within two weeks. At the beginning of each year, Meyersport gave DuPont an estimate of its annual requirement for each type of insulation. Meyersport also had to ensure the availability of a variety of other components such as D-rings, buckles, snaps, buttons, zippers, pull-strings with attached castings, and various labels and tags. Buckles, D-rings, pull-strings and buttons were procured locally in Hong Kong and had a 15- to 30- day lead time. Many snaps were purchased from German vendors; since snap lead times were long, Meyersport kept an inventory of snaps and dyed them locally as needed. Labels and tags had short lead times and were relatively inexpensive; Meyersport generally carried excess stock of these materials. Most zippers were purchased from YKK, a large Japanese zipper manufacturer. Myersport used a wide variety of zipper types each year. Zippers varied by length, tape color, and slider shape as well as the gauge, color, and material of the zipper teeth. Approximately 60% of Myersport's zipper requirements were sourced from YKK's Hong Kong factory, where standard zippers were manufactured. The lead time for these zippers was 60 days. The remainder were non-standard zippers, which were sourced from Japan with at least 90-day lead times—sometimes longer. YKK required a minimum order quantity of 500 yards if the dyeing color was a standard color from its catalog; if not, the minimum order quantity was 1,000 yards. All production materials were received by Myersport; materials for any given style were then collected and dispatched to the factory where the particular style was to be cut and sewn. Meyer products were produced in a number of different factories in Hong Kong and China. Cut and Sew A typical Meyer product required many cutting and sewing steps. (Exhibit 7 shows the sequence of sewing operations for the Rococo parka.) The allocation of operations to workers differed from one factory to another depending on the workers' level of skill and the degree of worker cross-training. Workers in Hong Kong worked about 50% faster than their Chinese counterparts. In addition to being more highly skilled, Hong Kong workers were typically trained in a broader range of tasks. Thus, a parka line in Hong Kong that required 10 workers to complete all operations might require 40 workers in China. Longer production lines in China led to greater imbalance in these lines; hence, a Hong Kong sewer's actual output during a given period of time was nearly twice that of a Chinese worker. (See Exhibit 8 for a comparison of Hong Kong and China operations. The cost components of the Rococo parka, which was produced in Hong Kong, are shown in Exhibit 9A. Exhibit 9B shows the estimated cost of producing the Rococo in China. Meyer sold the Rococo parka to retailers at a wholesale price of $112.50; retailers then priced the parka at $225.) Workers were paid on a piece-rate basis in both China and Hong Kong: the piece rate was calculated to be consistent with competitive wage rates in the respective communities. Wages in China were much lower than in Hong Kong; an average sewer in a Guangdong sewing factory earned US$0.16 per hour compared with US$3.84 per hour in the Alpine factory in Hong Kong. Workers in Hong Kong were also able to ramp up production faster than the Chinese workers. This ability, coupled with shorter production lines, enabled the Hong Kong factory to produce smaller order quantities efficiently. For parkas, the minimum production quantity for a style was 1,200 units in China and 600 units in Hong Kong. Meyer produced about 200,000 parkas each year. The maximum capacity available to the company for cutting and sewing was 30,000 units a month; this included the production capacity at all factories available to make Sport Meyer products. Meyersport was responsible for monitoring production and quality at all subcontractor factories. Workers from Meyersport inspected randomly selected pieces from each subcontractor's production before the units were shipped to the United States. Production Planning Wally's immediate concern was to determine an appropriate production commitment for the first half of Meyer's projected demand for the 1993-1994 season. He had estimated that Meyer earned 24% of wholesale price (pre-tax) on each parka it sold, and that units left unsold at the end of the season were sold at a loss that averaged 8% of wholesale price. Thus, for example, on a parka style such as the Rococo, which had a wholesale selling price of $112.50, Meyer's expected profit on each parka sold was approximately 24%($112.50) = $27, and its expected loss on each parka left unsold was approximately 8%($112.50) = $9. A Sample Problem To build his intuition about how to make production decisions, he decided to look at a smaller version of the company's problem. He looked at the Buying Committee's forecasts for the sample of 10 women's parkas2 (see Exhibit 10). Since these 10 styles represented about 10% of Meyer's total demand, to make this smaller version representative of the larger problem, he assumed he had cutting and sewing capacity of 3,000 units per month (10% of actual capacity) during the seven- month production period. Using these assumptions, Wally needed to commit 10,000 units for the first phase of production. The remaining 10,000 units could be deferred until after the Las Vegas show. Wally studied the Buying Committee's forecasts, wondering how he could estimate the risk associated with early production of each style. Was there some way he could use the differences among each member's forecast as a measure of demand uncertainty? An examination of demand from previous years indicated that forecast accuracy was the highest for those styles the Buying Committee had the highest level of agreement. (Technically, he found that the standard deviation of demand for a style was approximately twice the standard deviation of the Buying Committee's forecasts for that style.) With this in mind, he constructed a forecast distribution for each style as a normal random variable with the mean equal to the average of the Buying Committee member's forecasts and standard deviation twice that of the Buying Committee's forecasts (see Exhibit 11). Where to Produce To complete the planning decision, Wally would also need to decide which styles to make in Hong Kong and which would be better to produce in China. This year, Meyer expected to produce about half of all its products in China. Longer term, Wally wondered whether producing in China would constrain Meyer's ability to manage production and inventory risks. Would China's larger minimum order sizes limit the company's ability to increase the range of products it offered or to manage inventory risk? Was Meyer's trend toward increased production in China too risky given the uncertainty in China's trade relationship with the United States?

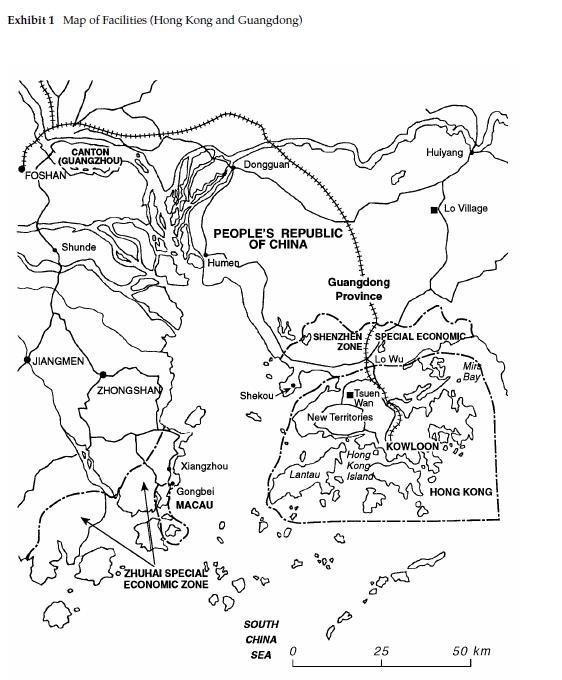

Exhibit 1 Map of Facilities (Hong Kong and Guangdong) CANTON (GUANGZHOU) FOSHAN Shunde JIANGMEN ZHONGSHAN Humea PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA Xiangzhou Gongbei MACAU ZHUHAI SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONE Dongguan 20 Shekou SOUTH CHINA SEA 0 Guangdong Province SHENZHEN ZONE Lantau Tsuen Wan New Territories SPECIAL ECONOMIC Lo Wu 6 Hong Kong Island Huiyang KOWLOON 25 Lo Village & Mira Bay HONG KONG 50 km

Step by Step Solution

3.44 Rating (154 Votes )

There are 3 Steps involved in it

In terms of operational changes Wally should focus on the following Reduce the number of styles that are in production Currently there are several styles and stock keeping units SKUs Improving lead ti... View full answer

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts