Question: Yeayyy.com: venturing into mobile app business Gearing up for the future Yeayyy.com was incorporated as a private limited company in February 2010. Its office was

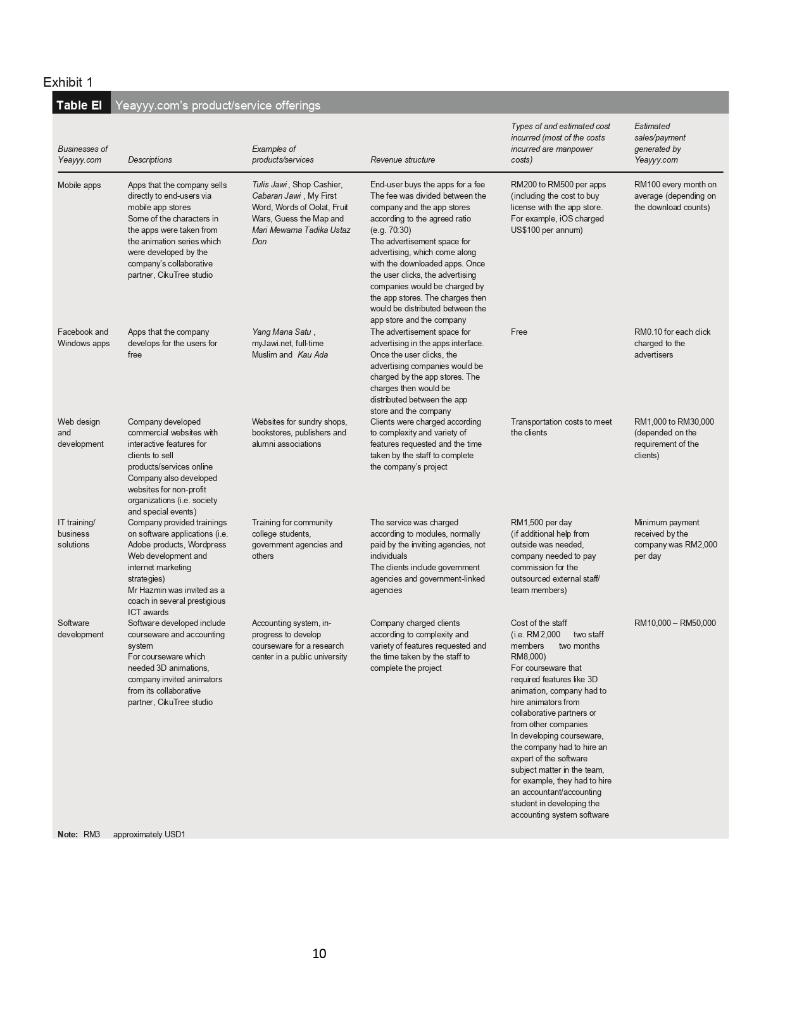

Yeayyy.com: venturing into mobile app business Gearing up for the future Yeayyy.com was incorporated as a private limited company in February 2010. Its office was located in Bandar Baru Bangi, Selangor, a township located about 30 km south of Kuala Lumpur. The company was founded by Mr Muhammad Hazmin Wardi (Mr Hazmin), whose main interest was in mobile game development. He started developing his first mobile game in 2007 and won a second place in a national-level mobile content competition. In the following year, he won the first t prize in another national-level mobile game competition. With the prize money in hand, Mr Hazmin was determined to start up a new venture to commercialize his inventions. In 2008, he enrolled in an intensive technopreneur program hosted by Multimedia Development Corporation (MDC). MDec was the central agency that facilitated the development of creative content industry in Malaysia. Upon completion of this program, Mr Hazmin bid for the Cradle seed funding and received RM150,000 (about US$50,000, with exchange rate of RM3 to approximately US$1) in 2010. He utilized the seed funding to form Yeayyy.com in the same year. By the end of 2013, the company's core businesses included developing mobile application (app), software and website, in addition to providing training for IT-related. By then, the company had commercialized a number of Mr Hazmin's mobile app inventions and had also developed a cartoon animation for a mobile app named Oolat Oolit. The company had also developed several other mobile apps, including a Jawi (traditional Malay writing system) app. several mobile games and Facebook apps. These mobile apps were compatible with Symbian, iOS and Android operating systems; thus, the apps could be utilized by many types of mobile phones. Since its inception, Yeayyy.com aspired for high-growth and benchmarked itself to the internationally acclaimed, home-grown production house Les' Copaque, which had produced the popular Upin Ipin animation series. Being a follower of Les' Copaque, Yeayyy.com also planned to commercialize its in-house animation characters into TV series and to market related merchandises, together with its collaborative partner, CikuTree Studio, However, by the end of 2014, the company's seed funding eventually depleted. Time was running out for Mr Hazmin, as the company's apps need to reach the market and achieve certain level of market penetration as soon as possible. Mr Hazmin knew that he had to implement a proper strategy for his company's future. Otherwise, the company's vision of becoming a leader in Web and mobile application development in Malaysia would not be achievable. Overview of the creative multimedia industry Mobile apps sector could be categorized under the broader creative multimedia industry, which comprised film production, advertising activities, architecture, animation and content; the digital content sector included games, mobile content and visual effects (Jamaluddin, 2014; KPKK, 2011). Creative multimedia industry was expanding and growing very fast in recent years. According to MDC (2014b), from 2011 to 2012, the industry had created an excess of RM0.3bn to the Malaysian gross domestic product (GDP) and had created 1,800 employments. By the end of 2013, the industry was estimated to be worth RM16bn (MDec, 2014b). To further develop the creative multimedia industry, the Malaysian Government had included the industry as one of the main focuses in the Ninth and Tenth Malaysia Plan for the year 2006-2014. In 2011, the Creative Industry National Policy was introduced, outlining the rationales, objectives, issues and challenges, as well as the strategies, to develop the industry and the action plan for the industry and the agencies responsible to execute the plan. The plan also included the disbursement of research grants and product development grants to industry players and incentives to attract local and foreign investors to the industry (KPKK, 2011). PAGE 1 Creative Industry Policy and related agencies to specifically support the development of the content sector of the creative multimedia industry, including the mobile app industry, the Malaysian Government had allocated several funds through the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI). MOSTI's main aim was to achieve knowledge generation, wealth creation and societal well-being through the advancement of science and technology in the country. Thus, the agency was responsible for developing science and technology industry in the country, one of which was the information and communications technology (ICT) industry. In support of the Creative Industry Policy, the Malaysian Government had also appointed MDeC to facilitate the development of this industry in terms of talent management, administration of incubators and dissemination of grants and linking the local industry players with international networks (MDec, 2014a). MDC oversaw the implementation of multimedia super corridor (MSC) Malaysia program, which was aimed at building a favourable environment to nurture the establishment of ICT small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The MSC status was given to ICT companies operated in Malaysia in which they had several privileges, including tax exemptions. In 2012, 309 MSC-status companies had operated in the creative multimedia industry and had contributed RM487m in the value of exports in the Malaysian GDP (MDec, 2014b). MDeC was also responsible for making evaluation and disbursement of the "cradle" or pre-seeding funds, seed funding and pre-commercialization funds allocated for the development of ICT and other types of technology-based ventures. These grants focused on supporting early-stage ventures. Very-early-stage ventures were eligible for pre-seeding funds, and they could be eligible for the seed funding and pre-commercialization later. These funds were disbursed according to the stages of the company development. The maximum amount of grants disbursed was also determined by the stage in which the companies were in. Pre-commercialized funds normally ranged from RM10,000 to 500,000, while commercialization fund might amount up to RM5m. Some of the companies under these programs had utilized these funds since before their inception until their products were successfully commercialized and generated returns. In support of the industry development, MDeC had also supported the development of networks with international industry players and had sought opportunities for joint venture, local and foreign investments into the industry, as well as other informal sources of funds (MDec, 2014a). Besides MDeC and MOSTI, another instrumental agency related to the creative multimedia industry in Malaysia was the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC). MCMC governed all acts related to the industry and promoted the development and self-regulation of the industry. The agency aimed to support development of creative multimedia content as a new source of national growth to achieve the country's aspiration to become a high- income nation (MCMC, 2014). Among others, MCMC managed the Creative industry development fund (CIDF) in which potential fund recipients were evaluated based on the level of the innovativeness of the content and the content should be compatible with several platforms, including third generation (3G)/mobile phone, internet or television (CIDF- MCMC, 2014). MCMC also worked together with MDeC to ensure further development of the industry. The two agencies regularly organized mobile app competitions in collaboration with other giant industry players. These initiatives were to support the efforts of entrepreneurs in product development and served as a source of fund for app developers to further enhance their apps to reach the commercialization stage. The cash prize for the national-level mobile app competitions NE was normally between RM5,000 and 50,000. Besides the cash prize, winners were occasionally offered to apply for grants of up to RM500,000. One of the competitions was the Intellectual Property Creator Challenge (IPCC), which was usually held annually. The competition was meant to support commercialization of projects of budding entrepreneurs the creative multimedia industry. Successful winners received up to RM60,000 grants, with only five to seven recipients each year. The competition duration was one month, and during that time, the participants were required to attend seminars and workshops organized by MDeC to equip them with appropriate skills to become a successful entrepreneur. The speakers for those programs were successful local and international entrepreneurs who shared their experiences with the participants (IPCC, 2014). Moreover, MDeC offered training development grants, including the Creative Lifelong Learning Program, which promoted lifelong learning for the creative multimedia industry players to enhance their skills and quality of their products; this program is aimed at developing the industry as a whole (CILL, 2014). Since 2009, MDeC had launched integrated content development (ICON) programs in the form of incentives for training and funding to individuals and companies aimed at supporting growth of mobile app development in the consumer, social and education markets (MDec, 2013; Bernama, 2012; MSC, 2014; MASTIC, 2014). 2 companies Another agency that managed government funds in support of the development of the ICT industry was the Malaysian Technology Development Corporation (MTDC), which was established in 1992. MTDC had in the recent years become the main agency to help in commercializing technology-based companies' products and services (MTDC, 2012). It served as one of the government's venture capital arm and also managed the disbursement of the Malaysian Ministry of Finance (MOF) funds, which include Business Start-up Fund (BSF). Business Growth Fund (BGF). Commercialisation of Research & Development Fund (CRDF) and Technology Acquisition Fund (TAF) from MOSTI, although the CRDF grants were mainly available for biotechnology companies (MTDC, 2012). Other types of funding for creative multimedia business Loans from banks were also available for small firms involved in the creative multimedia business, such as through the SME Bank. These companies were normally small-sized with ten employees or less. In addition, as the development of SMEs in Malaysia was facilitated by the Ministry of Domestic Trade, Co-operatives and Consumerism, these small companies might also receive support from agencies which were affiliated with this ministry or other agencies that directly facilitated the SME sector (MDTCC, 2014). However, these institutions usually would require collateral for loans of large amounts, which most of these small companies did not have. The funding for the creative multimedia might also come from angel investors. In Malaysia, angel funds comprised funds from individuals or organized funds that provide capital for a business start-up in return for convertible debt or ownership equity (Business Insider, 2014). Individual type of angel investing was usually based on entrepreneurs' own personal networks. The Government of Malaysia supported angel investing in the by establishing an agency under the MOF, called the Cradle Fund in 2003. The aim of the agency was to increase the number of in the country and to promote the funding assistantship by the on by the government to new start- technology (Bernama, 2012). Since the year of its establishment, Cradle Fund had managed a RM100m Cradle Investment Programme with an additional fund of RM50m from the Tenth Malaysia Plan (Cradle, 2014). In 2012, Cradle Fund had launched Malaysian Business Angel Network to function as a trade organization in creating a network of local and international angel investors. It also acted as the official accreditation body of angel investors in Malaysia (MBAN, 2012, 2014). As of early 2013, there were about four angel clubs and 150 individual investors with a total of RM10m worth of investment (Kumar, 2013). In the same year, the Malaysian Government began to implement tax incentives to angel investors in promoting growth of angel investment in the country (Business Insider, 2014; MBAN, 2012). of angel investors Another source of finance for technology-based ventures was through equity investment of venture capitalists. Venture capitalist comprised individuals or firms who invested in business ventures. They took a considerable risk when investing in start-up ventures and normally would have had an influence on the business decisions made by investee companies (OECD, 1996). In 2013, Malaysian Venture Capital Development Council reported that there were about 120 registered venture capitalists in Malaysia with about RM5.8bn funds. Government agencies had a share of about 60 per cent, local companies 20 per cent, foreign companies and individuals 12 per cent, banks 4 per cent, insurance 0.5 per cent, pension and provident funds 1 per cent and local individuals 2.5 per cent (MVCDC, 2014). By the end of 2013, the total investment of venture capital funds was about RM264m, with 41 per cent of the fund given to firms in the bridge or pre-initial public offering (IPO) or mezzanine stage, 35 per cent given at expansion or growth stage, 13 per cent given at early stage, 10 per cent given at start-up stage and 1 per cent given at seed stage. In terms of sectors, the amount of venture capital investments was 22 per cent in IT and communication, 19 per cent in manufacturing and 23 per cent in life sciences, whereas 36 per cent in other sectors (MV CDC 2014). In the mobile apps industry, it was usual for developers to participate in mobile app competitions. Apart from the opportunity to win cash prizes, developers were able to interact with one another and build their network. One of the most prestigious competitions was called "Hackathon", a "marathon" for the mobile app developers to gather and compete for prizes. In this competition, participants were given 24 h to develop their apps at a certain designated place. They might plan the apps earlier before the competition, but the coding and the executing works had to be completed on site within the stipulated timeframe. The prizes were in the form of cash prizes (worth up to RM60,000), bursaries and vacation trip tickets. The winning team would get personalized assistance by the sponsoring agencies to commercialize their apps to the market. Other than the government agencies such as MDeC and MCMC, companies too were often involved in organizing and sponsoring Hackathon events, for instance, ASTRO, Tune Talk and AT&T. 3 Mobile app industry Mobile app was a type of software that was developed for mobile devices. They can be installed into the customers' mobile devices from the mobile operating system's platform or "app store" (Statista, 2014; Suter, 2014). Mobile app industry was a part of the larger creative multimedia industry. The mobile app industry could be classified into eleven categories: educational; games, entertainment; social network; healthcare and fitness; money and finance, music; news and magazines; photo and video; travel and navigation; and utility (Roma et al., 2013). Worldwide, the mobile app market had grown significantly since the release of Apple's first iPhone in 2009. There were about 2.5 million downloads of mobile apps in 2009, and the number had increased to 138 million in 2014. The number of apps to be downloaded is predicted to increase to 270 million by 2017 (ETC, 2014). As of 2013, Apple had nearly one million apps offered in its App Store, and there were more numbers of apps in Google Play Store for the Android market (Rowinski, 2013). Based on the apps categories, games dominated the market with 18.3 per cent downloads; followed by education - 10.5 per cent business - 8.2 per cent; lifestyle - 8.2 per cent; and travel - 5 per cent (ETC, 2014). By the end of 2013, there were about 40 million Malaysians subscribed to mobile services with approximately 140 per cent mobile penetration. From this number, 51 per cent of mobile subscribers were smartphone users and 12 per cent were tablet users (MEF, 2014; Wong, 2014b). About 74 per cent of smartphone users play games through their device (Wong, 2014b), with Android users leading with 65 per cent of the total smartphone users. This was followed by the users of iOS - 13 per cent; Windows - 13 per cent; and Blackberry - 9 per cent (Wong, 2014a). In the same year, there were about 13 million users of Facebook, the leading social media platform in Malaysia, and about 50 per cent of the smartphone users access their social media accounts per week through mobile devices (Boo, 2013; Consumer Barometer, 2014; Mahadi, 2013). Mobile app developers might include individuals or organizations, and their mobile apps ranged from simple to complex with the costs ranging from low to very high costs. Simple were typically generic and less costly and took less time to develop, whereas complex app development was demanding and required highly skilled teams. Creating the first version of a basic app usually took at least three months to complete with costs that ranging from RM5,000 to 40,000. However, for apps that utilized database management system and content management, the cost could range from RM30,000 to 160,000, whereas apps that offered three-dimensional (3D) features might range from RM 160,000 to 1million (Ng, 2014a). Apps also needed to be designed separately for different operating systems, such as Apple's ios and Google's Android, or different platforms such as desktop computer or laptops, as they were not compatible to one another. As a result, developing the same app (or software) to be marketed on different platforms would require more cost (Ng, 2014a). In addition to developing apps that were made to customers' order, developers might profit from mobile app business through paid downloads and from advertisement services. For free apps, for instance, online advertisement marquee might appear or pop up on the mobile screen when the free app was in use. Other than paid apps and advertisements, some developers used the "freemium" model to get returns from the apps that they developed (Suter, 2014). "Freemium" apps applied the mechanism of in-app purchase, which allowed customers to download and use only the basic version of an app for free but charged them for access to premium features. For instance, customers would be required to pay should they wished to continue playing, use extended features or to unlock to a higher level in a game app. The charge, however, was usually nominal as the business model focused on volume rather than price. As such, mobile app providers would get more revenues when more mobile phone users upgraded their apps (Roma et al., 2013). Purchase of apps was also influenced by the type of operating system they utilized; most apps in Apple Store were not free, in comparison to Google Play Store, which provided more free options (Gudmundsdottir, 2014). The main factors contributing to high usage of mobile apps reportedly include positive word-of-mouth, consumers' curiosity to try out a new app and app's functionality and its ability to support communication with others (The Sun Daily, 2013). Apps were also chosen because of their mobility for use on the go, as in the case of apps for mobile map. Many mobile apps were also extensions of consumers' desktop internet apps, such as the apps for mobile banking, shopping or online ticketing. Many simple mobile apps were developed based on similar and generic concepts. For example, popular mobile games such as Candy Crush and Bejeweled applied the similar idea of "connecting three blocks to accumulate points. Similarly, Angry Birds and Castle Clash used the "pull-and-attack-the-target" concept. Another example was Al-Quran mobile apps, which were developed for the same purpose of Al-Quran reading and recitation; the differences were in the features, for example, having multiple sources of translations or lessons of tajweed (guidelines to the right way to recite Al-Quran). In addition, many simple mobile apps would not require high technology or high investment and thus, were easily imitated by competitors. In this situation, developers faced the uncertainties of predicting which app would eventually become a hit, and thus, they would require a differentiation strategy (Rakestraw et al., 2012). There were reported cases of companies manipulating the download counts in the app stores or their websites and generating fake reviews for their apps so that customers would be attracted to download the apps (Suter, 2014). Gartner (2014) predicted that majority of consumer mobile apps would be regarded as financial failures by their developers (only 0.01 per cent of the apps developed would be successful), as most of free apps were not directly contributing to profits. There was also a problem of retaining frequent users. According to a study in 2014, 20 per cent of mobile apps downloaded were only used once by the users (Localytics, 2014). As such, maintaining app usage over time by potential users was another issue that needs to be taken into consideration by developers when designing their products. Meanwhile, the demand for smartphones continued to increase, especially in recent years. International Data Corporation reported that mobile manufacturers shipped one billion smartphone devices worldwide in 2013, an increment of 38.4 per cent as compared to 2012 (Gudmundsdottir, 2014). The increased demand for smartphones resulted in the industry becoming diversified and segmented. Many smartphone manufacturers began to offer a lot of featured apps pre-installed in the phone as a differentiation strategy. As such, app developers had to increase the breadth of their products and services by developing and offering many apps, rather than focusing on only a few apps. However, it was also essential for developers to identify which of the apps were more popular so that they could focus on marketing only signature apps that might bring in more revenues (Lessin and Ante, 2014; Roma et al., 2013). In Malaysia, approximately 120,000 employees were involved in mobile app development, which represented about 40 per cent of the total employees in ICT sectors (MASTIC, 2013). Despite ICT being one of the five major education streams as identified by the Malaysian Ministry of Education, there was a gap between the numbers of ICT graduates and their employability the country. From about 7,000 of the first-degree ICT graduates in 2013, only 10 per cent joined the IT industry as new entrants, whereas others needed more training and experience before they were able to join the industry (MOE, 2014; PIKOM, 2014). The situation might also be due to a lower remuneration rate in comparison to other industries (MASTIC, 2013). Malaysian ICT workers' salary, which rose by about 7.2 per cent in 2013, was still behind many other countries such as Vietnam and Hong Kong (Ng, 2014b; PIKOM, 2014). It was reported that this remuneration issue could also be the reason for the decreasing trends in the number of student enrollment in IT-related degrees in the country (MASTIC, 2013). Inception of Yeayyy.com and its product development This section chronicled the development of Yeayyy.com and the description of the products and services offered by the company 2007-2010 In 2007, Mr Hazmin, then an undergraduate student of Interactive Media at a Malaysian technical university, entered a mobile app competition using his final-year project following the advice of his supervisor. For the competition, he mapped his idea and asked his friend to illustrate some cartoon characters and features to be inserted into the app. His mobile app concept was an edutainment" (education and entertainment) game app for mobile phone targeting children aged between six and nine years. The app was classified under edutainment category, as it served to provide simple mathematical lessons to children while letting them play with colourful and interactive cartoon characters. 5 In this game, the player role-played as a shop cashier. After clicking on the button "Start", a number of glossaries of items would appear. The items ranged from toys, candies and ice-creams sold in a number of shops. The player would be asked the amount of things bought by a buyer and calculate how much change that they needed to return to the buyer, and this must be done within a time frame. The game used four simple mathematic operations (i.e. addition, subtraction, multiplication and division) to solve the problems with three levels of difficulty. This game concept was similar to other popular edutainment mobile games that used question-answer concept, such as the games of Dora the Explorer and Go-Diego-Go. Together with his friend who helped with the illustrations, Mr Hazmin worked on this game for almost three months under close guidance from his supervisor. They later used this game concept for the Mobile Content Challenge competition organized by the MCMC and Maxis in 2007. The team won second place, with a cash prize of RM20,000 During the competition, a mentor company was assigned to the team. The mentor company was impressed with the game and was interested to commercialize it. However, because the game was developed while Mr Hazmin was a student, the game was considered an intellectual property of the university. The mentor company later bought an outright licensing from the university to proceed with commercialization. The mentor company too had sponsored the game's registration at the Nokia Ovi Store, allowing Nokia users to download it from the store. For each download, the app store charged 30 per cent from the selling price. The game had attracted a number of Nokia users on the Symbian platform in Malaysia and other countries. The game app was later redesigned and made available for Android platform that formed the majority of global mobile phone users. After Mr Hazmin won the competition and graduated in August 2007, he continued to develop his game and other apps while looking for ways to build his own company. He recognized the potential of creative multimedia industry while training with his mentor company. Mr Hazmin attended seminars, conferences and exhibitions to gain knowledge of the industry and to network with other experienced industry players around the world. In 2008, Mr Hazmin joined another competition, the IPCC organized by MDec, where he created mobile app named Jawi Fun. The app let users read and write Jawi, the traditional writing system of Malay language that used modified Arabic characters. At that time, Mr Hazmin figured that Jawi-related apps were of high potential to be well received in Malaysia, and thus began to develop more Jawi-based mobile apps. Besides creating a new niche market for Jawi enthusiasts, Mr Hazmin envisioned that the development of such apps might help to revive the public's interest about the Malay heritage that had been largely ignored by younger generations. In that competition, he won the first prize in the mobile edutainment category with a cash prize of RM50,000. With RM70,000 in hand, Mr Hazmin was confident and thought that he was finally ready to start up his own company. However, he needed further assurance, and at the end of 2008, he decided to join Creative Technopreneur Academy Program (C-TAP) in Malacca. During this course, 30 trainees underwent intensive training to set up their own ICT business. This was the point where Mr Hazmin realized the challenges faced by entrepreneurs. At the end of the course, all trainees had the opportunity to apply for a RM150,000 Pre-Seed Fund from MDC. Mr Hazmin's business proposals were continually rejected by a panel of judges from MDeC, MOF, MCMC and industry representatives who reviewed the applications with highest scrutiny, Mr Hazmin had to spend a lot of time, money and efforts to keep improving and resubmitting his business plans. Many of his fellow trainees withdrew from the course during this phase. Mr Hazmin's application was finally approved on the fourth attempt and was awarded the fund in early 2010. 2010 In 2010, Mr Hazmin established a private limited company, called Yeayyy Sdn. Bhd (Yeayyy.com), a private limited company to commercialize Web and mobile apps that were developed by his team. Mr Hazmin related his situation at that time: I've graduated at the end of 2007. At that time, I was lucky as the goverment was focusing on developing the creative multimedia cluster. Then, I receive the MDeC seed funding, which is the best kind of funding you could get as the money is disbursed upfront, while for other types of grants, we will have to spend our own money first, then only got the reimbursement. So this fund is the best for me, when I graduated, the fund was already available. Otherwise, I will not be able to become an entrepreneur (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication, November 13, 2013). At this point of the company's inception, Mr Hazmin served as the Managing Director and appointed a good friend of him to be the Project Manager. Mr Hazmin started his company with the RM150,000 Pre-Seed Fund. The company declared that its authorized capital was RM100,000 and paid-up capital was RM50,000. The vision of the company was to become a leader in Web and mobile application development in Malaysia, with a mission to re-engineer the Web and mobile apps to the next level (Yeayyy.com, 2014). At that time, the company employed less than ten staff in support of its product development, including designing animation cartoons. Even before starting up the company, Mr Hazmin was aware that his company might not survive on mobile gaming business alone. Besides mobile games, the company developed software, courseware and games for computers. The company also offered Web development services. In addition, Mr Hazmin also generated income through consultation and training services. The courses were designed to provide trainings and tutorials to the participants on computer software for IT solutions, including topics of publishing, photo editing, website developing and internet marketing. His company also had a collaborative partner which aimed to produce its own cartoon, animation to be broadcasted at a local television channel soon. The partner was CikuTree Studio, which developed the 3D animation characters, such as Ustaz Don (for Tadika Ustaz Don series) and Oolat Oolit, and Yeayyy.com would develop the mobile apps based on these characters. As the intellectual property rights were owned by CikuTree, Yeayyy had to pay royalties to its partner from the revenue obtained by the apps. However, he needed to continuously create new mobile games. Mr Hazmin related the challenges he faced: The mobile game industry was a challenging industry as the players were not corta in which type of game would hit the market in the future. Sometimes, whether a product would sell depended on luck or good marketing strategy. Mr Hazmin had hired freelance artists to create the illustrations of the cartoon concepts that he had in mind, whereas other employees helped out with the daily operation of the company. Mr Hazmin did not have a formal education entrepreneurship. He claimed that he learned about businesses from the courses he attended and the advices from his friends who had ventured into businesses earlier than him. Mr Hazmin rented a small space in a shoplot at Bandar Baru Bangi, which was owned by his trainer during the C-TAP program. Mr Hazmin lamented about his business setup: in this industry, one neither needs a huge space of business premise nor many employees in the company Moreover, it was normal for employees in this industry to switch companies. In other words, when the company had a job, employees work with this company. When the job had finished, the employees then would work with other companies that got a job. I know of one big animation company, which had permanent staff of only about 30 to 40 people, when it has big projects, they would hire 80 to 100 staff to help them. Then, when the projects ended, many staff had to quit (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication, November 13, 2013) 2011-2013 In 2011, Mr Hazmin and his team had successfully created an animation named Oolat Oolit, two caterpillar characters, who were usually accompanied by some other bug friends. Oolat Oolit were featured as the main characters in most of Yeayyy.com mobile apps and games. Oolat Oolit mascots frequently appeared in events organized or joined by Yeayyy.com's team, such as coloring contests and other children activities. The company had also focused on developing and producing more Jawi apps. Exhibit 1 lists the products and services of Yeayyy.com, including mobile apps and Facebook/ Windows apps. Mr Hazmin felt that it was important for him to participate in a Hackathon, especially those that were organized by grant providers. This was because of the fact that Yeayyy.com had to show its visibility and updates to the funding agencies. Moreover, competitions enabled companies to gauge their skills and standing in the industry, as well as to get new ideas from others' projects. Competitions also became the "meeting place" for developers to interact and seek help with each other. For example, Mr Hazmin had outsourced a specialized training session that he lacked expertise to one of the experts that he had met during Hackathons. Mr Hazmin said: When we join Hackathons, we know people (pause) who can do this or that, so that we can cooperate. For example, I got this multimedia project training in about two weeks. The training meant to cover five types of software. Three of my team members are already there, but I need two more people. So I contacted the people whom I got to know during Hackathon. I did not know that this guy has a company, which does video. He said he made videos using Make Up Pro and Motion, and Mac video editing. So I am going to take him in to be involved in the training. So, during competition, we compete, after competition, we become friends (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication March 5, 2014). 7 Mr Hazmin also emphasized on the need for having multi-skilled team members when participating in competitions: In a Hackathon, it was important for the participants to form a team. It was because all team members had their own skills, including coding skill designing skill, and presenting/pitching skill. This was the recipe for success. However, it was a challenge for me as I did not have much money to form such teams. Sometimes I went to a Hackathon by myself and did all the 24-hour works. The result was / felt so exhausted at the pitching session and could not do well. So I have to think of a strategy to form a Hackathon team which always ready to join other future Hackathons (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication, April 9, 2014). In Yeayyy.com, the cost to develop an app depended on the number of staff involved and time taken for them to achieve completion. The rate of remuneration to be paid to the staff, on the other hand, would depend on their skills and expertise in the development. As such, the higher the human skills required to develop the app, the higher the costs of development. According to Mr Hazmin, well-featured apps were needed to attract advertisers. Usually, advertisers were reluctant to put their advertisements for generic apps because of their perceived low potential for them to reach users and possibly less attractive to be downloaded. Mr Hazmin also added that to develop a full-featured app, it was practical for a developer to conceive the app from scratch. Although developers could opt to use existing platforms or open source or free codings, the end result usually would not be very good. Therefore, to develop attractive apps, the developer had to spend a considerable amount of time to understand the language of the program and the software development kit (SDK) of the platform and to design the corresponding features appropriately. Mobile app also was not able to be fully optimized if viewed from a computer or from different platforms such Facebook because of their different SDK properties. This situation demanded developers to understand each language and features of different platforms and to develop different app versions compatible with Android, iOS, Facebook, Windows and Symbian. As at 2014, there was no single software or a language able to serve multiple platforms at the same time. As such, more staff and time needed to develop these apps and to meet variations in the platform standards. One of the alternative strategies to develop a mobile app was to buy the existing codes that were already commercialized. The cost of buying these codes was usually affordable. After integrating some additional features, the developer could put his own brand name on the apps. This process was called reverse engineering of app development. By using this strategy, the developer could gain more profit, as the cost of development was much lesser. In addition, such apps were usually visible in the marketplace, as their general functions were already well known to users (for instance, Photo Editor or Prayer Time apps), thus increasing the chance for the apps to be downloaded and used. In this industry, a mobile app was typically marketed directly to the app store. Mobile apps could also be marketed through rebranding them under syndicated game publishers, such as Electronic Arts. Through the syndicated game publishers, customers all around the world would be able to download the apps from the publishers' websites. The publishers would charge some amount from the sales for their profit . Besides the syndicates, another popular option to market the apps was through the app stores, which was a platform built by big operating system companies that assembled thousands of apps/games in the stores for easy access to customers. The examples of such apps stores include Apple Store for Apple's iOS, Nokia Ovi Store for Nokia's Symbian, Google Play Store for Android and BlackBerry Worlds for Blackberry OS. What's next for Yeayyy.com? Yeayyy.com faced a lot of challenges because of the industry's uncertainties. The company would hire more staff when it had jobs and retrench them when the job was done. By the end of 2013, Mr Hazmin and his team had almost exhausted the seed funding. In 2014, Mr Hazmin had planned to focus exclusively in developing his own mobile apps and training modules. However, because of the financial constraints, had to continue to offer services of developing websites and courseware for clients. By that time, the company's Tulis Jawi app (an expanded version of Jawi Fun app) had attracted about 170,000 downloads in the Android market and was considered the only successful app developed by the company. However, the company did not have a proper team and the resources to further develop other apps and to increase their market share. 8 Mr Hazmin was also involved as a training instructor in events organized by agencies that supported the development of IT industry in Malaysia, such as MDeC and MCMC. According to Hazmin, training services generated good money, and he was working toward developing his own training modules to maximize the earnings made from these training services. This decision, however, was taking a toll on his mobile app business, as the development of many apps was being delayed. Mr Hazmin related his company's situation in 2014: IT Company gets money through two ways. One, give service to others, and second develop our own products, like a big animation house, which now does not take development job from others. I know that if I want to survive in the long run, I have to create my own products. Having the company's own characters in apps development would give us a competitive advantage, when the characters become popular. Earlier this year I had planned not to do service for others anymore, because I will need to spend two to three months to finish the job But I still had to do it to support the company (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication, April 9, 2014) In regard to conducting trainings and providing services to develop websites and courseware for clients, Mr Hazmin related: For websites, we charged according to the clients' budget. The more complicated the works, or the more time is needed for the works, the higher the charges. For training, the demand is there, so the money is always good. However, for the time being, Yeayyy.com was only able to attract small-sized jobs, as Mr Hazmin lamented: In this industry, the competition is based on size. For example, I just got this university project, which worth about RM50,000. AL first, this chent contacted the bigger production houses, but they said they would not do small projects. So, they asked the university to find us. So, it is my portion. That means, each company size has its own markets, big companies serve big projects, small companies do small projects (Muhammad Hazmin, personal communication, March 5, 2014). Since the company's inception four years ago, Mr Hazmin had been adamant on not looking for venture capitals. He stated that "I do not want to let go of shares in Yeayyy [...] to investors, like in the case of many others in the industry In the end, the founders might get side-lined". Mr Hazmin's insistence, however, started to waver as he faced more and more challenges in managing his business. Yeayyy.com had to be fast to tap the mobile app market; however, lack of funds would certainly hinder the company's growth. As the seed funding had almost depleted by the end of 2014, time was running out for Mr Hazmin, as he needed to decide on what strategies would be required for his business to survive. More so, now being a family man, his new family was also counting on his company's survival. 9 Exhibit 1 Table El Yeayyy.com's product/service offerings Businesses of Yeayyy.com Types of and estimated cost incurred (most of the costs incurred are manpower costs) Edinated sales/payment generated by Yeayyy.com Descriptions Examples of products Services Revenue structure Mobile apps Apps that the company sells directly to end-users via mobile app stores Some of the characters in the apps were taken from the animation series which were developed by the company's collaborative partner, CkuTree studio Tinis law Shop Cashier. Cabaran Jawi, My First Ward, Words al Oolat Frut Wars, Guess the Map and Mtan Mewame Tadika Ustaz Dan RM200 to RM500 por apps (including the cost to buy license with the app store For example, iOS charged US$100 per annum) RM100 every month on average (depending on the download counts) End-user buys the apps for a foe The fee was divided between the company and the app stores according to the agreed ratio (e.g. 70:30) The advertisement space for advertising, which come along with the downloaded apps. Once the user clicks, the advertising companies would be charged by the app stores. The charges then would be distributed between the app store and the company The advertisement space for advertising in the apps interface Once the user dicks, the advertising companies would be charged by the app stores. The charges then would be distributed between the app store and the company Clients were charged according to complexity and variety of features requested and the time taken by the staff to complet the company's project Facebook and Free Windows apps Apps that the company develops for the users for free Yang Mana Satu myJawi.net, full-time Muslim and Kau Ada RM0.10 for each dick charged to the advertisers Web design and development Webstes for sundry shops, bookstores, publishers and alumni associations Transportation costs to meet the clients RM1,000 to RM30.000 (depanded on the requirement of the clients) IT training business solutions Training for community college students, government agencies and others Company developed commercial websites with interactive features for dients to all products/services online Company also developed websites for non-profit Organizations ie society and special events) Company provided trainings on software applications .. Adobe products, Wordpress Web development and internet marketing strategies) Mr Hazmin was invited as a coach in several prestigious ICT awards Software developed include Courseware and accounting system For courseware which needed 3D animations, company invited animators from its collaborative partner, CkuTree studio The service was charged according to modules, normally paid by the inviting agencies, not individuals The dients indude government agencies and government-inked agendes RM 1 500 par day (if additional help from outside was needed company needed to pay Commission for the outsourced external staff team members) Minimum payment received by the company was RM2,000 per day RM10,000 - RM50,000 Software development Accounting system, il- progress to develop courseware for a research center in a public university Company charged clients according to complexity and variety of features requested and the time taken by the staff to complete the project Cost of the staff ( fie RM2,000 two staff members bwo months RM8000) For courseware that required features the 30 animation, company had to hire animators from colaborative partners or from other companies In developing courseware, the company had to hire an expert of the software subject matter in the team, for example, they had to hire an accountant/accounting student in developing the accounting system software Note: RM approximately USD1 10 Answer ALL FIVE (5) questions below: QUESTION 5 What approaches would you use in financing the company's plans? - The End- -The End 11 Yeayyy.com: venturing into mobile app business Gearing up for the future Yeayyy.com was incorporated as a private limited company in February 2010. Its office was located in Bandar Baru Bangi, Selangor, a township located about 30 km south of Kuala Lumpur. The company was founded by Mr Muhammad Hazmin Wardi (Mr Hazmin), whose main interest was in mobile game development. He started developing his first mobile game in 2007 and won a second place in a national-level mobile content competition. In the following year, he won the first t prize in another national-level mobile game competition. With the prize money in hand, Mr Hazmin was determined to start up a new venture to commercialize his inventions. In 2008, he enrolled in an intensive technopreneur program hosted by Multimedia Development Corporation (MDC). MDec was the central agency that facilitated the development of creative content industry in Malaysia. Upon completion of this program, Mr Hazmin bid for the Cradle seed funding and received RM150,000 (about US$50,000, with exchange rate of RM3 to approximately US$1) in 2010. He utilized the seed funding to form Yeayyy.com in the same year. By the end of 2013, the company's core businesses included developing mobile application (app), software and website, in addition to providing training for IT-related. By then, the company had commercialized a number of Mr Hazmin's mobile app inventions and had also developed a cartoon animation for a mobile app named Oolat Oolit. The company had also developed several other mobile apps, including a Jawi (traditional Malay writing system) app. several mobile games and Facebook apps. These mobile apps were compatible with Symbian, iOS and Android operating systems; thus, the apps could be utilized by many types of mobile phones. Since its inception, Yeayyy.com aspired for high-growth and benchmarked itself to the internationally acclaimed, home-grown production house Les' Copaque, which had produced the popular Upin Ipin animation series. Being a follower of Les' Copaque, Yeayyy.com also planned to commercialize its in-house animation characters into TV series and to market related merchandises, together with its collaborative partner, CikuTree Studio, However, by the end of 2014, the company's seed funding eventually depleted. Time was running out for Mr Hazmin, as the company's apps need to reach the market and achieve certain level of market penetration as soon as possible. Mr Hazmin knew that he had to implement a proper strategy for his company's future. Otherwise, the company's vision of becoming a leader in Web and mobile application development in Malaysia would not be achievable. Overview of the creative multimedia industry Mobile apps sector could be categorized under the broader creative multimedia industry, which comprised film production, advertising activities, architecture, animation and content; the digital content sector included games, mobile content and visual effects (Jamaluddin, 2014; KPKK, 2011). Creative multimedia industry was expanding and growing very fast in recent years. According to MDC (2014b), from 2011 to 2012, the industry had created an excess of RM0.3bn to the Malaysian gross domestic product (GDP) and had created 1,800 employments. By the end of 2013, the industry was estimated to be worth RM16bn (MDec, 2014b). To further develop the creative multimedia industry, the Malaysian Government had included the industry as one of the main focuses in the Ninth and Tenth Malaysia Plan for the year 2006-2014. In 2011, the Creative Industry National Policy was introduced, outlining the rationales, objectives, issues and challenges, as well as the strategies, to develop the industry and the action plan for the industry and the agencies responsible to execute the plan. The plan also included the disbursement of research grants and product development grants to industry players and incentives to attract local and foreign investors to the industry (KPKK, 2011). PAGE 1 Creative Industry Policy and related agencies to specifically support the development of the content sector of the creative multimedia industry, including the mobile app industry, the Malaysian Government had allocated several funds through the Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI). MOSTI's main aim was to achieve knowledge generation, wealth creation and societal well-being through the advancement of science and technology in the country. Thus, the agency was responsible for developing science and technology industry in the country, one of which was the information and communications technology (ICT) industry. In support of the Creative Industry Policy, the Malaysian Government had also appointed MDeC to facilitate the development of this industry in terms of talent management, administration of incubators and dissemination of grants and linking the local industry players with international networks (MDec, 2014a). MDC oversaw the implementation of multimedia super corridor (MSC) Malaysia program, which was aimed at building a favourable environment to nurture the establishment of ICT small and medium enterprises (SMEs). The MSC status was given to ICT companies operated in Malaysia in which they had several privileges, including tax exemptions. In 2012, 309 MSC-status companies had operated in the creative multimedia industry and had contributed RM487m in the value of exports in the Malaysian GDP (MDec, 2014b). MDeC was also responsible for making evaluation and disbursement of the "cradle" or pre-seeding funds, seed funding and pre-commercialization funds allocated for the development of ICT and other types of technology-based ventures. These grants focused on supporting early-stage ventures. Very-early-stage ventures were eligible for pre-seeding funds, and they could be eligible for the seed funding and pre-commercialization later. These funds were disbursed according to the stages of the company development. The maximum amount of grants disbursed was also determined by the stage in which the companies were in. Pre-commercialized funds normally ranged from RM10,000 to 500,000, while commercialization fund might amount up to RM5m. Some of the companies under these programs had utilized these funds since before their inception until their products were successfully commercialized and generated returns. In support of the industry development, MDeC had also supported the development of networks with international industry players and had sought opportunities for joint venture, local and foreign investments into the industry, as well as other informal sources of funds (MDec, 2014a). Besides MDeC and MOSTI, another instrumental agency related to the creative multimedia industry in Malaysia was the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC). MCMC governed all acts related to the industry and promoted the development and self-regulation of the industry. The agency aimed to support development of creative multimedia content as a new source of national growth to achieve the country's aspiration to become a high- income nation (MCMC, 2014). Among others, MCMC managed the Creative industry development fund (CIDF) in which potential fund recipients were evaluated based on the level of the innovativeness of the content and the content should be compatible with several platforms, including third generation (3G)/mobile phone, internet or television (CIDF- MCMC, 2014). MCMC also worked together with MDeC to ensure further development of the industry. The two agencies regularly organized mobile app competitions in collaboration with other giant industry players. These initiatives were to support the efforts of entrepreneurs in product development and served as a source of fund for app developers to further enhance their apps to reach the commercialization stage. The cash prize for the national-level mobile app competitions NE was normally between RM5,000 and 50,000. Besides the cash prize, winners were occasionally offered to apply for grants of up to RM500,000. One of the competitions was the Intellectual Property Creator Challenge (IPCC), which was usually held annually. The competition was meant to support commercialization of projects of budding entrepreneurs the creative multimedia industry. Successful winners received up to RM60,000 grants, with only five to seven recipients each year. The competition duration was one month, and during that time, the participants were required to attend seminars and workshops organized by MDeC to equip them with appropriate skills to become a successful entrepreneur. The speakers for those programs were successful local and international entrepreneurs who shared their experiences with the participants (IPCC, 2014). Moreover, MDeC offered training development grants, including the Creative Lifelong Learning Program, which promoted lifelong learning for the creative multimedia industry players to enhance their skills and quality of their products; this program is aimed at developing the industry as a whole (CILL, 2014). Since 2009, MDeC had launched integrated content development (ICON) programs in the form of incentives for training and funding to individuals and companies aimed at supporting growth of mobile app development in the consumer, social and education markets (MDec, 2013; Bernama, 2012; MSC, 2014; MASTIC, 2014). 2 companies Another agency that managed government funds in support of the development of the ICT industry was the Malaysian Technology Development Corporation (MTDC), which was established in 1992. MTDC had in the recent years become the main agency to help in commercializing technology-based companies' products and services (MTDC, 2012). It served as one of the government's venture capital arm and also managed the disbursement of the Malaysian Ministry of Finance (MOF) funds, which include Business Start-up Fund (BSF). Business Growth Fund (BGF). Commercialisation of Research & Development Fund (CRDF) and Technology Acquisition Fund (TAF) from MOSTI, although the CRDF grants were mainly available for biotechnology companies (MTDC, 2012). Other types of funding for creative multimedia business Loans from banks were also available for small firms involved in the creative multimedia business, such as through the SME Bank. These companies were normally small-sized with ten employees or less. In addition, as the development of SMEs in Malaysia was facilitated by the Ministry of Domestic Trade, Co-operatives and Consumerism, these small companies might also receive support from agencies which were affiliated with this ministry or other agencies that directly facilitated the SME sector (MDTCC, 2014). However, these institutions usually would require collateral for loans of large amounts, which most of these small companies did not have. The funding for the creative multimedia might also come from angel investors. In Malaysia, angel funds comprised funds from individuals or organized funds that provide capital for a business start-up in return for convertible debt or ownership equity (Business Insider, 2014). Individual type of angel investing was usually based on entrepreneurs' own personal networks. The Government of Malaysia supported angel investing in the by establishing an agency under the MOF, called the Cradle Fund in 2003. The aim of the agency was to increase the number of in the country and to promote the funding assistantship by the on by the government to new start- technology (Bernama, 2012). Since the year of its establishment, Cradle Fund had managed a RM100m Cradle Investment Programme with an additional fund of RM50m from the Tenth Malaysia Plan (Cradle, 2014). In 2012, Cradle Fund had launched Malaysian Business Angel Network to function as a trade organization in creating a network of local and international angel investors. It also acted as the official accreditation body of angel investors in Malaysia (MBAN, 2012, 2014). As of early 2013, there were about four angel clubs and 150 individual investors with a total of RM10m worth of investment (Kumar, 2013). In the same year, the Malaysian Government began to implement tax incentives to angel investors in promoting growth of angel investment in the country (Business Insider, 2014; MBAN, 2012). of angel investors Another source of finance for technology-based ventures was through equity investment of venture capitalists. Venture capitalist comprised individuals or firms who invested in business ventures. They took a considerable risk when investing in start-up ventures and normally would have had an influence on the business decisions made by investee companies (OECD, 1996). In 2013, Malaysian Venture Capital Development Council reported that there were about 120 registered venture capitalists in Malaysia with about RM5.8bn funds. Government agencies had a share of about 60 per cent, local companies 20 per cent, foreign companies and individuals 12 per cent, banks 4 per cent, insurance 0.5 per cent, pension and provident funds 1 per cent and local individuals 2.5 per cent (MVCDC, 2014). By the end of 2013, the total investment of venture capital funds was about RM264m, with 41 per cent of the fund given to firms in the bridge or pre-initial public offering (IPO) or mezzanine stage, 35 per cent given at expansion or growth stage, 13 per cent given at early stage, 10 per cent given at start-up stage and 1 per cent given at seed stage. In terms of sectors, the amount of venture capital investments was 22 per cent in IT and communication, 19 per cent in manufacturing and 23 per cent in life sciences, whereas 36 per cent in other sectors (MV CDC 2014). In the mobile apps industry, it was usual for developers to participate in mobile app competitions. Apart from the opportunity to win cash prizes, developers were able to interact with one another and build their network. One of the most prestigious competitions was called "Hackathon", a "marathon" for the mobile app developers to gather and compete for prizes. In this competition, participants were given 24 h to develop their apps at a certain designated place. They might plan the apps earlier before the competition, but the coding and the executing works had to be completed on site within the stipulated timeframe. The prizes were in the form of cash prizes (worth up to RM60,000), bursaries and vacation trip tickets. The winning team would get personalized assistance by the sponsoring agencies to commercialize their apps to the market. Other than the government agencies such as MDeC and MCMC, companies too were often involved in organizing and sponsoring Hackathon events, for instance, ASTRO, Tune Talk and AT&T. 3 Mobile app industry Mobile app was a type of software that was developed for mobile devices. They can be installed into the customers' mobile devices from the mobile operating system's platform or "app store" (Statista, 2014; Suter, 2014). Mobile app industry was a part of the larger creative multimedia industry. The mobile app industry could be classified into eleven categories: educational; games, entertainment; social network; healthcare and fitness; money and finance, music; news and magazines; photo and video; travel and navigation; and utility (Roma et al., 2013). Worldwide, the mobile app market had grown significantly since the release of Apple's first iPhone in 2009. There were about 2.5 million downloads of mobile apps in 2009, and the number had increased to 138 million in 2014. The number of apps to be downloaded is predicted to increase to 270 million by 2017 (ETC, 2014). As of 2013, Apple had nearly one million apps offered in its App Store, and there were more numbers of apps in Google Play Store for the Android market (Rowinski, 2013). Based on the apps categories, games dominated the market with 18.3 per cent downloads; followed by education - 10.5 per cent business - 8.2 per cent; lifestyle - 8.2 per cent; and travel - 5 per cent (ETC, 2014). By the end of 2013, there were about 40 million Malaysians subscribed to mobile services with approximately 140 per cent mobile penetration. From this number, 51 per cent of mobile subscribers were smartphone users and 12 per cent were tablet users (MEF, 2014; Wong, 2014b). About 74 per cent of smartphone users play games through their device (Wong, 2014b), with Android users leading with 65 per cent of the total smartphone users. This was followed by the users of iOS - 13 per cent; Windows - 13 per cent; and Blackberry - 9 per cent (Wong, 2014a). In the same year, there were about 13 million users of Facebook, the leading social media platform in Malaysia, and about 50 per cent of the smartphone users access their social media accounts per week through mobile devices (Boo, 2013; Consumer Barometer, 2014; Mahadi, 2013). Mobile app developers might include individuals or organizations, and their mobile apps ranged from simple to complex with the costs ranging from low to very high costs. Simple were typically generic and less costly and took less time to develop, whereas complex app development was demanding and required highly skilled teams. Creating the first version of a basic app usually took at least three months to complete with costs that ranging from RM5,000 to 40,000. However, for apps that utilized database management system and content management, the cost could range from RM30,000 to 160,000, whereas apps that offered three-dimensional (3D) features might range from RM 160,000 to 1million (Ng, 2014a). Apps also needed to be designed separately for

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts