During the mid-1980s, Stephen W. Gray owned and operated a small CPA firm in Columbia, Mississippi.1 Located

Question:

During the mid-1980s, Stephen W. Gray owned and operated a small CPA firm in Columbia, Mississippi.1 Located in south-central Mississippi near the banks of the Pearl River, Columbia’s population of 5,000 provided Gray with only a modest client base and limited potential for revenue growth. In 1987, Gray struck upon an idea to expand his practice. For several years, Gray had offered financial planning services to his clients. After developing a financial plan for a customer, Gray referred the individual to a securities broker. The broker then purchased the appropriate investments for the customer. After obtaining a broker’s license in June 1987, Gray became affiliated with a Texas-based investment firm, H. D. Vest Investment Securities, Inc., and began offering brokerage services to his clients.

Gray took several steps to protect the integrity of his CPA status after he began providing brokerage services. To safeguard his independence on attest engagements, he refused to provide brokerage services to clients for whom he performed audits and other attestation services. Gray also adopted a strict policy of informing clients that he would earn commissions on securities trades they placed through him. Finally, to make his customers and the general public aware of his dual professional roles, he prominently displayed his broker’s license within his office. Gray realized that accepting commissions violated the ethical code of the Mississippi State Board of Public Accountancy. Since 1973, the state agency had vigorously enforced a ban on the receipt of commissions by CPAs. This ban included commissions received exclusively from non-attest clients.

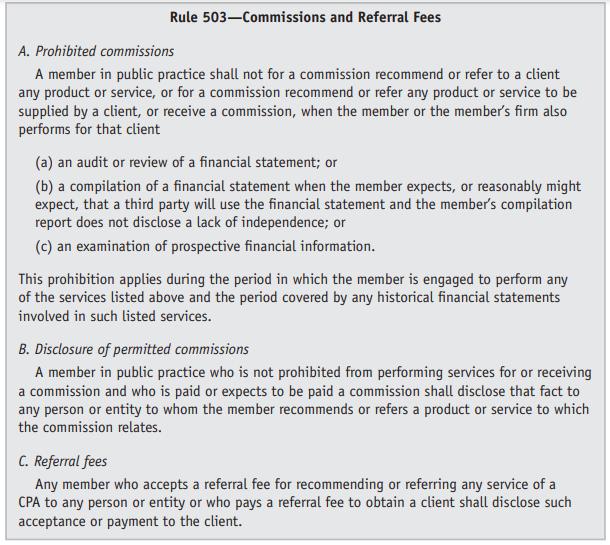

When he applied for a broker’s license in 1987, Gray was also keenly aware of an ongoing confl ict between the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the American Institute of Certifi ed Public Accountants (AICPA). That confl ict involved the FTC’s efforts to force the AICPA to allow its members to accept commissions from nonattest clients. The FTC prevailed in 1988 when the AICPA’s ruling Council voted 191 to 5 to allow members to accept commissions for certain services provided to non-attest clients.2 Rule 503 of the AICPA’s Code of Professional Conduct, shown in Exhibit 1, expresses the AICPA’s present stance regarding the receipt of commissions by its members.

In late 1990, a CPA alerted the Mississippi State Board of Public Accountancy that he had evidence Stephen Gray was accepting commissions in exchange for brokerage services. The CPA stumbled across this evidence while providing accounting services to a former client of Gray. Following a brief investigation, the state board charged Gray with violating its ban against accepting commissions. At an April 19, 1991, hearing before the state agency, Gray acknowledged that he had accepted commissions from non-attest clients. Gray then maintained that the state board had exceeded its statutory authority when it adopted the ban on commissions. He also argued that the rule was not in the public interest.

The Mississippi state board patiently listened to Gray’s arguments. One month later, the board voted to revoke Gray’s CPA certificate and his license to practice. Gray immediately appealed that decision, an appeal heard by the Marion County Circuit Court. During the lengthy appeals process, Gray retained both his CPA certifi cate and license to practice. In reviewing the state board’s decision, the circuit court placed considerable weight on the AICPA rule that allowed CPAs to receive commissions from non-attest clients. The court noted that 46 state boards of accountancy, including the Mississippi state board, prohibited CPAs from receiving such commissions. But then the court went on to observe that it was even more impressive “that the national association of all CPAs specifically allows for the receipt of commissions.”

The circuit court also questioned whether the ban on receiving commissions improperly infringed on CPAs’ ability to earn a livelihood. CPAs who ply their trade in the more remote areas of the state, the court observed, were particularly subject to being harmed by this rule. The circuit court proposed a control procedure to mitigate conflicts of interest that might arise from allowing CPAs to accept commissions for non-attest services. This procedure would require CPAs to fi le a report with the state board disclosing the non-attest services they provided on a commission basis. These reports would also require disclosure of the relationship, if any, between the non-attest and attest services offered by a CPA.

Questions

1. Why do professions adopt ethical codes for their members? What factors cause professions to change these codes over time?

2. In your opinion, did the Mississippi State Board of Public Accountancy make an appropriate decision when it eventually chose not to revoke Stephen Gray’s CPA certificate and license to practice? Defend your answer.

3. Suppose that a CPA’s spouse holds a broker’s license. Would the CPA violate Rule 503 of the AICPA’s Code of Professional Conduct if the spouse provides brokerage services on a commission basis to an attest client of the CPA?

4. Compare and contrast the oversight roles within the accounting profession of state boards of public accountancy and the AICPA. What is the role of state societies of CPAs in the accounting profession?

Exhibit 1

Step by Step Answer:

Contemporary Auditing Real Issues And Cases

ISBN: 9780538466790

8th Edition

Authors: Michael C. Knapp