Paul Polishan graduated with an accounting degree in 1969 and immediately accepted an entry-level position in the

Question:

Paul Polishan graduated with an accounting degree in 1969 and immediately accepted an entry-level position in the accounting department of The Leslie Fay Companies, a women’s apparel manufacturer based in New York City. Fred Pomerantz, Leslie Fay’s founder, personally hired Polishan. Company insiders recall that Pomerantz saw in the young accounting graduate many of the same traits that he possessed. Both men were ambitious, hard driving, and impetuous by nature.

After joining Leslie Fay, Polishan quickly struck up a relationship with John Pomerantz, the son of the company’s founder. John had joined the company in 1960 after earning an economics degree from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1972, the younger Pomerantz became Leslie Fay’s president and assumed responsibility for the company’s day-to-day operations. Over the next few years, Polishan would become one of John Pomerantz’s most trusted allies within the company. Polishan quickly rose through the ranks of Leslie Fay, eventually becoming the company’s chief financial officer (CFO) and senior vice president of finance.

Leslie Fay’s corporate headquarters were located in the heart of Manhattan’s bustling garment district. The company’s accounting offices, however, were 100 miles to the northwest in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. During Polishan’s tenure as Leslie Fay’s top accounting and fi nance offi cer, the Wilkes-Barre location was tagged with the nickname “Poliworld.” The strict and autocratic Polishan ruled the Wilkes-Barre site with an iron fist. When closing the books at the end of an accounting period, Polishan often required his subordinates to put in 16-hour shifts and to work through the weekend. Arriving two minutes late for work exposed Poliworld inhabitants to a scathing reprimand from the CFO. To make certain that his employees understood what he expected of them, Polishan posted a list of rules within the Wilkes-Barre offices that documented their rights and privileges in minute detail. For example, they had the right to place one, and only one, family photo on their desks. Even Leslie Fay personnel in the company’s Manhattan headquarters had to cope with Polishan’s domineering manner. When senior managers in the headquarters office requested financial information from Wilkes-Barre, Polishan often sent them a note demanding to know why they needed the information.

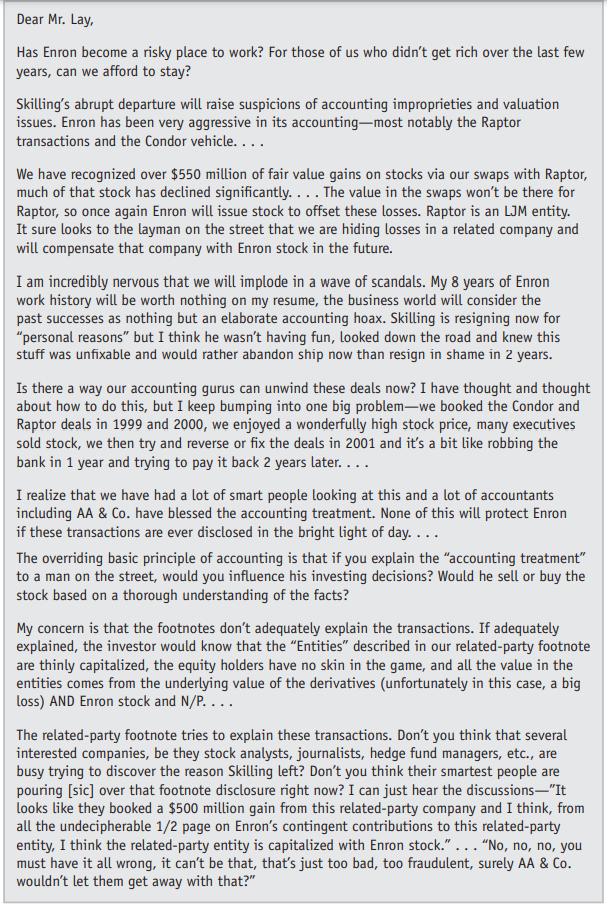

Polishan’s top lieutenant at the Wilkes-Barre site was the company controller, Donald Kenia. On Polishan’s frequent trips to Manhattan, Kenia assumed control of the accounting offices. Unlike his boss, Kenia was a soft-spoken individual who apparently enjoyed following orders much more than giving them. Because of Kenia’s meek personality, friends and coworkers were stunned in early February 1993 when he took full responsibility for a large accounting fraud revealed to the press by John Pomerantz. Investigators subsequently determined that Leslie Fay’s earnings had been overstated by approximately $80 million from 1990 through 1992.

Following the public disclosure of the large fraud, John Pomerantz repeatedly and adamantly insisted that he and the other top executives of Leslie Fay, including Paul Polishan, had been unaware of the massive accounting irregularities perpetrated by Kenia. Nevertheless, many parties inside and outside the company expressed doubts regarding Pomerantz’s indignant denials. Kenia was not a major stockholder and did not have an incentive-based compensation contract tied to the company’s earnings, meaning that he had not benefited directly from the grossly inflated earnings figures he had manufactured. On the other hand, Pomerantz, Polishan, and several other Leslie Fay executives held large blocks of the company’s stock and had received substantial year-end bonuses, in some cases bonuses larger than their annual salaries, as a result of Kenia’s alleged scam. Even after Kenia pleaded guilty to fraud charges, many third parties remained unconvinced that he had directed the fraud. When asked by a reporter to comment on Kenia’s confession, a Leslie Fay employee and close friend of Kenia indicated that he was a “straight arrow, a real decent guy” and then went on to observe that, “something doesn’t add up here.”1 Similar to many of his peers, Fred Pomerantz served his country during World War II. But instead of storming the beaches of Normandy or pursuing Rommel across North Africa, Pomerantz served his country by making uniforms—uniforms for the Women’s Army Corps. Following the war, Pomerantz decided to make use of the skills he had acquired in the military by creating a company to manufacture women’s dresses.

He named the company after his daughter, Leslie Fay. His former subordinates and colleagues in the industry recall that Pomerantz was a “character.” Over the years, he reportedly developed a strong interest in gambling, enjoyed throwing extravagant parties, and reveled in shocking new friends and business associates by pulling up his shirt to reveal knife scars he had collected in encounters with ruffians in some of New York’s tougher neighborhoods. Adding to Pomerantz’s legend within the top rung of New York’s high society was his lipstick-red Rolls Royce that he used to cruise up and down Manhattan’s crowded streets.

Pomerantz’s penchant for adventure and revelry did not prevent him from quickly establishing his company as a key player in the volatile and intensely competitive women’s apparel industry. From the beginning, Pomerantz focused Leslie Fay on one key segment of that industry. He and his designers developed moderately priced and stylishly conservative dresses for women age 30 through 55. Leslie Fay’s principal customers were the large department store chains that fl ourished in major metropolitan areas in the decades following World War II. By the late 1980s, Leslie Fay was the largest supplier of women’s dresses to department stores. At the time, Leslie Fay’s principal competitors included Donna Karan, Oscar de la Renta, Nichole Miller, Jones New York, and Albert Nipon. But, in the minds of most industry observers, Liz Claiborne, an upstart company that had been founded in 1976 by an unknown designer and her husband, easily ranked as Leslie Fay’s closest and fiercest rival. Liz Claiborne was the only publicly owned women’s apparel manufacturer in the late 1980s that had larger annual sales than Leslie Fay......

Questions

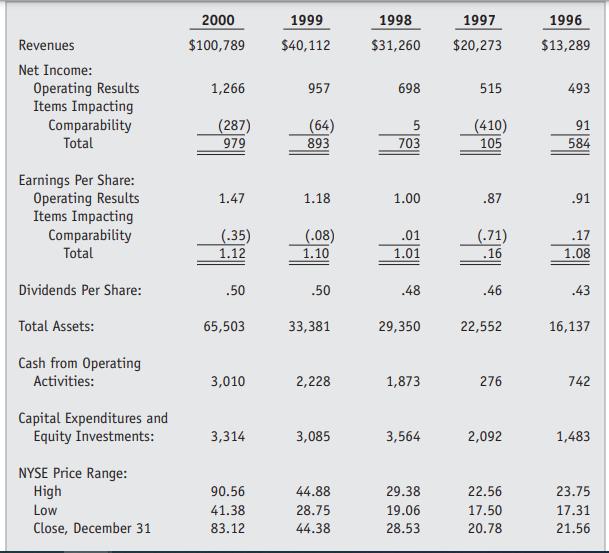

1. Prepare common-sized financial statements for Leslie Fay for the period 1987–1991. For that same period, compute for Leslie Fay the ratios shown in Exhibit 2. Given these data, which fi nancial statement items do you believe should have been of particular interest to BDO Seidman during that firm’s 1991 audit of Leslie Fay? Explain.

2. In addition to the data shown in Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2, what other financial information would you have obtained if you had been responsible for planning the 1991 Leslie Fay audit?

3. List nonfinancial variables or factors regarding a client’s industry that auditors should consider when planning an audit. For each of these items, briefly describe their audit implications.

4. Paul Polishan apparently dominated Leslie Fay’s accounting and financial reporting functions and the individuals who were his subordinates. What implications do such circumstances pose for a company’s independent auditors? How should auditors take such circumstances into consideration when planning an audit?

5. Explain why the SEC ruled that BDO Seidman’s independence was jeopardized by the lawsuits that named the accounting firm, Leslie Fay, and top executives of Leslie Fay as co-defendants.

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 2

Step by Step Answer:

Contemporary Auditing Real Issues And Cases

ISBN: 9780538466790

8th Edition

Authors: Michael C. Knapp