The United States and the Commonwealth of Australia have long been strong and mutually supportive allies.1 However,

Question:

The United States and the Commonwealth of Australia have long been strong and mutually supportive allies.1 However, the two countries’ close relationship was threatened recently by an international scandal referred to in the Sydney Morning Herald, Australia’s oldest and most prominent newspaper, as the “worst corruption scandal in Australian history.”2 At the center of this scandal was AWB Limited, a large public company that had been granted a government monopoly over the export of all wheat from that country. During the United Nations embargo imposed on Iraq following that country’s invasion of Kuwait, AWB became the largest supplier of wheat to Iraq. AWB’s wheat sales to Iraq were made through the United Nations (U.N.) Oil-for-Food Program, a program intended to provide humanitarian relief to Iraqi citizens during the lengthy U.N. embargo.

Following the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime by U.S.-led coalition forces in 2003, allegations surfaced that AWB had secured the Iraqi wheat contracts by agreeing to pay bribes to the former dictator. The U.N. formed a task force headed by Paul Volcker, the former chairman of the United States’ Federal Reserve System, to investigate those allegations. In late 2005, the task force reported that AWB had paid nearly $300 million in bribes to Saddam Hussein’s regime beginning in the late 1990s. AWB management had been told by Iraqi governmental officials that if the bribes were not paid, the company would be denied the huge wheat contracts.

A former AWB officer testified that one of his superiors approved the payment of the Iraqi bribes. In defense of those illicit payments, the superior told this individual, “We are in the business of maximizing opportunities and sales returns” and, as a result, “we shouldn’t jeopardize our business with Iraq”3 [by refusing to pay the bribes demanded by Saddam Hussein]. After the fact, some AWB stockholders defended the company’s decision to capitulate to Saddam Hussein’s demands. “We have had enough of this free market bulls. When you do business with Saddam, you do business the way he tells you.”4 The AWB scandal created a brouhaha between Australia’s two leading political parties, the Liberal Party and the Labor Party. Political opponents of Prime Minister John Howard, the leader of the Liberal Party, charged that he and his subordinates had approved AWB’s decision to secretly funnel bribes to Saddam Hussein to secure the lucrative Iraqi wheat contracts. In referring to those bribes, a spokesperson for the Labor Party noted that, “This is the single biggest lump of money in the world paid to the Iraqi dictator, straight out of Australia, approved by the Australian government.”

Criticism of Prime Minister Howard was not confined to Australia. U.S. wheat farmers and several large U.S. wheat exporters, such as Cargill, Inc., were incensed by the revelations of how AWB had obtained the Iraqi wheat contracts and insisted that the United States take appropriate measures to punish Australia. U.S. Senator Norm Coleman of Minnesota, a leading spokesperson for U.S. wheat producers, publicly criticized Prime Minister Howard and suggested that, at a minimum, the prime minister had been aware that AWB was paying the bribes. This accusation prompted an irate Prime Minister Howard, who had long been an ardent supporter of the United States and its Middle Eastern policies, to demand an apology from the U.S. government, an apology that the prime minister never received. The Australian government created the Australian Wheat Board in 1939 to provide economic assistance to the country’s wheat farmers. Many of the nation’s wheat farmers had struggled to survive the Great Depression of the 1930s that had caused just as much, if not more, economic misery in Australia as it had in the United States. For the next five decades, all wheat grown in Australia had to be sold to the Australian Wheat Board at a price established by the federal agency. In 1989, Australia’s federal government deregulated the nation’s domestic wheat market, but any wheat that was to be exported, which was the bulk of the nation’s annual harvest, still had to be sold to the Australian Wheat Board. The Australian Wheat Board pooled the wheat purchased each year for export and then marketed it principally to developing countries around the world. Proceeds from the sale of the wheat were then distributed on a pro rata basis to Australia’s wheat farmers.

In 1999, Australia’s federal government converted the Australian Wheat Board into AWB Limited, a private company with two classes of common stock. AWB’s Class A common stock was distributed to the country’s wheat farmers. This stock is nontransferable and must be sold back to AWB if an individual stops growing wheat. In 1991, AWB’s Class B common stock was sold on the Australian Stock Exchange for the first time. Class B stock can be purchased by anyone, but Australian law prohibits any individual or institution from accumulating more than 10 percent of those shares. Since 9 of the 11 seats on AWB’s board of directors are chosen by the Class A stockholders, Australia’s wheat farmers exercise effective control over the company.........

Questions

1. Many foreign companies sell securities on U.S. stock exchanges. Do the provisions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act apply to those companies?

2. Under current U.S. auditing standards, what responsibility, if any, does an audit firm of a multinational company have to discover bribes that are paid by the client to obtain or retain international business relationships? In a bullet format, list audit procedures that may be effective in uncovering such payments.

3. Suppose you discover during the course of an audit engagement that the audit client is routinely making “facilitating payments” in a foreign country. What are the key audit-related issues, if any, posed by this discovery?

4. A quote in this case from an Australian newspaper suggested that many corporate boards in the United States believe that they “have no social responsibility beyond that of making profits for their shareholders.” In your opinion, what level of “social responsibility,” if any, do corporate boards have? Defend your answer.

5. The audit report shown in Exhibit 1 refers to “Australian Auditing Standards.” What organization issues Australian Auditing Standards? What is the relationship, if any, between Australian Auditing Standards and International Standards of Auditing?

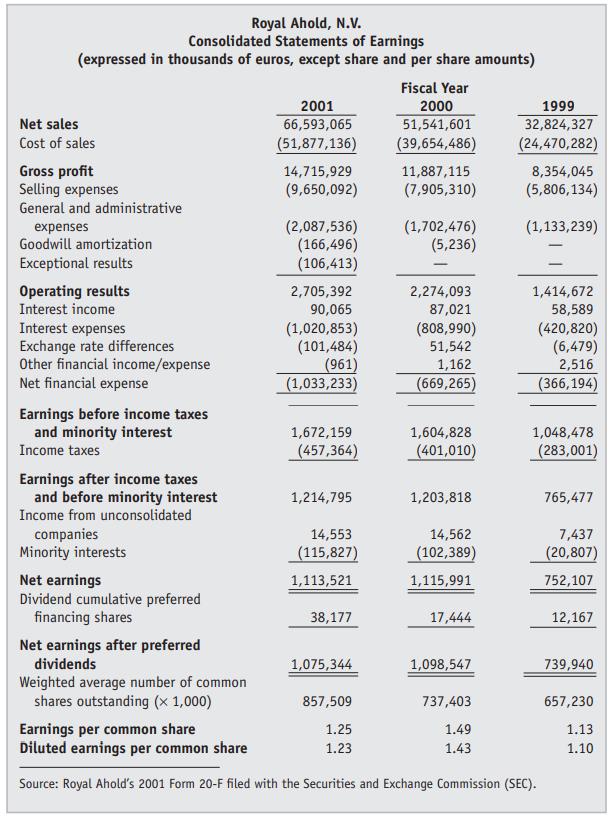

Exhibit 1

Step by Step Answer:

Contemporary Auditing Real Issues And Cases

ISBN: 9780538466790

8th Edition

Authors: Michael C. Knapp