Doug Brenhouse leaned back in his office chair and took a moment to himself away from the

Question:

Doug Brenhouse leaned back in his office chair and took a moment to himself away from the turmoil involved with the biggest decision of his professional life. Should he and his two co‐founders, John Frank and Erik Rauch, accept the funding and terms that Sevin Rosen and its syndicate of three other VC firms had on the table? Three years after creating MetaCarta, a software start‐up building a product that converts unstructured textual information into maps (geographic search versus the text searches of Google), the team needed money, but who should they take money from, and what were the implications of those investors? The current deal, if accepted, would dramatically change both the ownership structure and the day‐to‐day control of the company. Doug wondered if the team was ready to relinquish so much control over the growth of their firm.

Doug’s History Doug Brenhouse’s background was a combination of entrepreneurship and engineering. In his family, owning a small business was “the norm.” His father was a partner in a wood products manufacturing company. Two of Doug’s uncles owned a women’s clothing store chain, and the other was an independent home builder. One of his aunts was an independent insurance agent, and many of his friends’ parents also had businesses of their own. With entrepreneurs to his left and right, Doug considered that he too would eventually pursue his entrepreneurial ambitions. It was just a question of when the time would be right.

In 1996, Doug earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering with a minor in management from McGill University.

After graduation, he joined Active Control Experts, Inc., a small company that designed piezoelectric actuators in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The company used specialized ceramics that produce an electric current when physical force is exerted onto them. The technology applied to vibration dampening in aviation, sound production in speakers, and physical shock absorption in sporting goods, such as skis2 and mountain bikes.3 The company had been founded only four years earlier and retained its start‐up culture. In 1997, Inc. magazine named Active Control Experts the 79th fastest growing private company in America.4 Doug learned a lot working for an earlystage entrepreneurial company and thought that this experience was preparing him for his own venture. After three years with the company, Doug wanted to explore the option of founding his own company.

In 1999, Doug enrolled in Babson College’s MBA program. As he was about to enter his second year, Babson created a new program where students could apply their studies directly to launching a new venture. Doug stated, “Babson was a natural fit. In addition to the standard business education, I was able to walk the path of the first seven months of a business while actually starting one.” Doug spent the early part of the program trying to figure out what kind of business to start. Doug looked at a variety of opportunities. Doug recalled:

One of the best places to see what kind of opportunities were emerging was the MIT 50 k Business Plan Competition.

There was a social mixer at the beginning of the year. Everyone was gathering around big dishes of food.

It was almost like speed dating, just trying to meet as many people as you could. Here, I met my business plan competition team [John Frank and Erik Raush]. John was a very charismatic guy. It seemed like [his idea] was more than just putting together some students for a business plan competition. I could sense that John was going to launch this business regardless of the outcome of the 50k.5 Pattie Maes,6 Founder and Director of MIT Media Lab’s Fluid Interface Group, had advised John to go find a partner with business expertise. Serendipitously, John and Doug had come to the MIT 50k looking for the same thing; someone with complementary skills to partner with. Through this introductory social event, the three‐member founding team was established.

Erik’s and John’s Backgrounds Erik Rauch was a brilliant scholar and somewhat eccentric. He had a peculiar hobby of recording in his journal places with odd names, such as Hopeulikit, Georgia, and North Pole, Arkansas.

His fascination with places and maps helped him see the potential that would eventually be MetaCarta. He enrolled in Yale University in 1992, earning the Morton B. Ryerson Scholarship.

During his time there, he excelled at computer science and related mathematics. Erik was a research assistant in both Yale’s Mathematics and Computer Science Departments. His work included writing an algorithm for floating‐point variable optimization and using computer programming for fractal geometry simulation. Erik graduated from Yale in 1996. He went on to work in the Theoretical Physics Department at IBM’s T. J. Watson Research Center and to study graduate‐level computer science at Stanford University, before beginning his work toward a PhD in artificial intelligence at MIT.

John Frank began his pursuit of scientific expertise at Yale University, earning his bachelor’s degree in physics in 1999. While at Yale, he completed an internship with IDEO, a renowned design and innovation consulting firm. He was also the Team Director of “Team Lux—Yale Undergraduates Racing with the Sun.” This was a student‐led team that built and raced a solar‐powered vehicle in the 1,250 mile Sunrayce 97 competition, finishing ninth out of 56 teams. After graduating from Yale, John began his doctoral studies in physics at MIT. At MIT, he first conceived of the software applications that would shape the next 10 years of his life and also enlisted Erik’s help to build the software.

John’s Idea

John Frank encountered a problem for a class he was taking at MIT. He was doing a project on how trees affected rainfall in the South Pacific. To conduct this research, he had to compare the vegetation on an island to a variety of other climatic features of each geographic area he examined. He needed to locate all the weather station information on each island and no matter what Internet search he tried to construct, he couldn’t get access to all of the data he needed. John thought, wouldn’t it be great if I could take a map, put it on top of the island and use that as the filter? Then I could find everything about this geography and get back the information that I need, and I would not have to know the names of all the different knolls and hills and stations that people refer to when they write about that location.

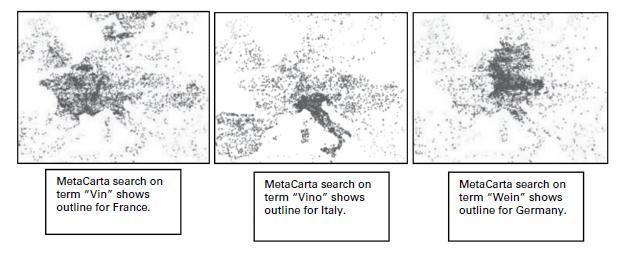

Traditional search engines can use specific text, such as the name of a city or river, to relate locations with other search terms. John wanted to create software that could search through online information and unstructured documents and identify which specific geographic location that document is referring to. This would include associating a mention of the “Potomac River” with the states that it runs through, as well as recognizing that a reference to “approximately 200 miles northeast of New York City” should most likely be connected with the area near Boston, Massachusetts. In other words, this search engine would build maps based on textual data. The initial program they developed was able to produce locations on a map based on search terms. For example, if you wanted to search wine, a map would be generated that showed all the locations related to wine. You could even search in different languages. The maps7 below illustrate different results based on a search term.

John possessed solid programming skills, but he needed someone with superior expertise to develop his concept into potentially revolutionary software. He brought his idea to Erik Rauch. John and Erik had known each other from their time at Yale. Knowing Erik’s experience with doctoral‐level artificial intelligence programming, John enlisted his help.

Forming a Founding Team

Doug, John, and Erik understood that their collective ability to work together was crucial to the success of the venture.

According to Doug: It is very much like getting married. You have to “date” for a while and really like the person that you are going to “marry.” We ended up “dating” for four months or so before deciding that the business was worth pursuing and incorporating. We spent a lot of time together. Both socially and working on the business. Both were equally important.

We got to know each other’s friends and family pretty quickly. On the “work” side, it was like feeling around in the dark. We were doing a lot of research into what business models might make sense, what other companies were doing, how we packaged what we had and pitched it to investor—there was a lot of trial and error, and we got to see how we each dealt with different situations, where each other’s strengths and weaknesses were, and as it turned out, we complemented each other incredibly well.

Things were moving fast. The trio incorporated MetaCarta in January and started to raise money. This violated the MIT 50k rules, and the team was initially disqualified until one of MetaCarta’s advisors convinced the 50k committee to let the team compete. Unfortunately, Doug and his partners did not win, but the competition was another opportunity for the three students to test their “fit” as a team. With John and Erik providing the technical expertise and Doug articulating the business proposition, the team chemistry was strong and Doug knew this was the opportunity he was looking for.

Dynamics of the Founding Team

All three of the founding members shared science and engineering backgrounds. From this common foundation, their skills branched out in different directions:

[We had] very complementary skills. Erik was very technical. Big brain, it made sense for him to be pursuing a PhD in Artificial Intelligence. John spanned the gamut: very capable, very good at explaining technology. His father was a CEO of a variety of businesses. Besides good DNA, I think that he picked up a lot at the dinner table about how to be charismatic and how to run a business. My skills, though I have an engineering background, were much more on the business side, running and managing the business.

The MetaCarta founders needed to decide how to structure their fledgling team before attempting to develop the idea into a business. They anticipated the need for help from more experienced executives in later stages. Their initial titles reflected that expectation:

We all fit into our roles extremely well. We intentionally took on roles where we expected “C” level [hires] to come on. We had these grand visions of growth of the company.

I took a VP role and John took the President role thinking that a CEO and a COO would [join at a later date]. Erik was initially Chief Scientist. He was continuing his PhD studies and was part‐time.

Dividing the Equity

John, Doug, and Erik arranged a division of equity in the company before they had a concrete valuation of the business.

If they had waited until after starting the process of seeking financing to decide how to share ownership among the founders, it could have been a much more complicated decision. By agreeing soon after their initial formation of the company simplified the decision because factors such as the influence of the investors, the complexity of proposed investment deal terms, and changing priorities of all the involved parties did not confuse the decision.

We all recognized our equity positions were reliant on the value over time and not their immediate worth. We all had the mind‐set of vesting [the equity] over a period of three years. We realized that if the team dynamics didn’t work, for whatever reason, there would be enough equity to entice [a new hire] to fill the role.

The Business Model

MetaCarta’s original business model was to allow free access to its search product online. The company would monetize its service through Internet advertising.

This was 2000. The dot‐com boom was well underway.

Internet advertising was tremendous and what made the most sense was that you could create a geographic search engine. Then folks who advertise on the Internet, like McDonalds or Nike, might be willing to pay more for their advertisement on a map that was driving real purchasers into their physical stores. The story was resonating with early investors, and we raised \($100,000\).

Everything was going as planned, but then came the dot‐com bust, and the stock market fell apart practically overnight, and there was [no longer the same level of]

Internet advertising dollars. So the idea of selling Internet advertising at a premium disappeared. We thought, “Now, what should we do?” We thought hard and long and changed the business model.

Instead of providing a free search engine to the public, the MetaCarta team thought the capability would be useful as an enterprise search engine…government agencies, Fortune 500 companies…although the new business model did not target as large of a market, the core customer was clear, and the value proposition meant that the customer should be willing to pay for the product.

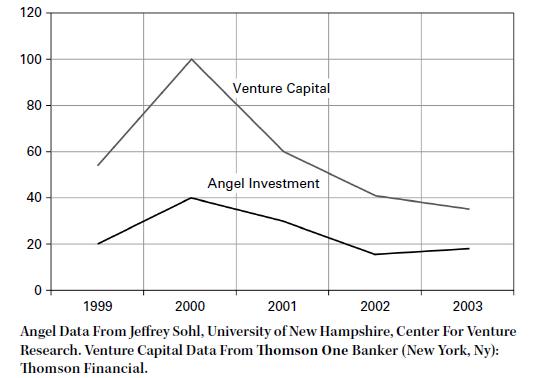

Difficulty Raising Capital

Now the team had to raise money based on this different business model. Getting money on the new business model was difficult. The angel investor community and venture capital firms had recently been shaken by the stock market crash, resulting in a plunge in early‐stage investing. The following chart shows total dollars invested per year by venture capitalists (VCs) and angels. As can be seen, 2001–2003 was not a strong period relative to the recent past to raise capital. The team’s new mantra became, “There is no bad time to start a business,” but Doug wondered if they were deluding themselves.

MetaCarta needed capital at precisely the time when it was most difficult for a software company to find funding.

It was incredibly hard work. We talked to everybody that we possibly could. It was all about getting to the next conversation and not getting discouraged. This was a time where the Internet bubble had crashed. A bunch of folks were sitting around not interested in spending their money on technology, but still wanted to get together [for angel investor meetings] for social reasons. We went and pitched, and some of the guys were asleep. They would ask questions that were intended, it seemed, to derail the opportunity. There was lots of criticism and very little [of it] was constructive. We would go to talk to people, and they would look you in the eye and say, “We just don’t get it. We think that you guys are idiots. This doesn’t make any sense to me.”

I remember that we went to one local VC firm, and we pitched to them. We were explaining one of our potential markets, oil and gas, to them and why [that was so attractive]. We already had Chevron interested as an investor and potential customer. The venture capital folks asked, “Why do people in the oil and gas industry need to read documents?” This person at a prominent venture capital firm in Boston just could not comprehend why this technology would be important.

Alternative Financing: DARPA In October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first human‐built object to orbit the Earth. Military experts at the time believed that the technology that launched Sputnik was the first step in developing intercontinental nuclear missiles.8 The United States hoped to launch a satellite of its own within six months, albeit one far smaller than Sputnik. In addition to the U.S. satellite project, the federal government created DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency).

This agency’s mission was to provide research and funding to develop technologies that could be used by the U.S. military and, in some cases, the public as well. Because of the difficulty in securing conventional financing, MetaCarta explored an unconventional funding source: DARPA.

Doug and his team were successful in securing \($500,000\) in funding. DARPA funding was a big step for us. It allowed us to move out of John’s living room and into an office and add a few talented people to the team. We also started taking small salaries for ourselves.

Getting the DARPA money was a big boost to the team.

Not only could they pay themselves and hire more talent, but the DARPA money came in the form of a grant. No dilution.

Furthermore, DARPA provided credibility to the team and their project. John and Doug soon realized that although this infusion was welcome, they needed more. The company was continuing to grow quickly and that required additional financing.

Angels

Although the angel investment community had still not recovered, John and Doug decided to go back to solicit angel investment.

We ended up raising money from family, friends, and business connections. We also got introductions to local software luminaries in the Boston area, some from MIT, and some from different angel groups in town. Pitching to angels was starting to wear on us. We often left those meetings asking ourselves, “Why did we do this again?

Right, because this is what we do.” At the end of the day, we ended up meeting some great people in Boston, who introduced us to some other great people. As we managed to pick up one, then two, then four, then eight, we managed to bring together a great group of investors in Boston. The same was true for New York. We ended up hooking up with three partners from Goldman Sachs. One introduced us to another, who introduced us to [the third]. We had a contingent in Boston and a contingent in New York. They were great to work with.

Valuing the company at such an early stage presented a challenge for the founding team. Even after identifying interested investors, terms of the deal would shape the company’s future. If John, Doug, and Erik demanded too high a valuation, some investors would lose interest. Too low of a valuation would lead to an erosion of their founders’ equity as financing rounds progressed. Once the first investor in a particular round would come to an agreement with the founders on the terms of the deal, the other potential investors interested in the round would be faced with a “take it or leave it” ultimatum. Furthermore, most early‐stage investors, including both angel investors and venture capitalists, write clauses into their investment contracts that prevent such dilution, often at the expense of the founders.

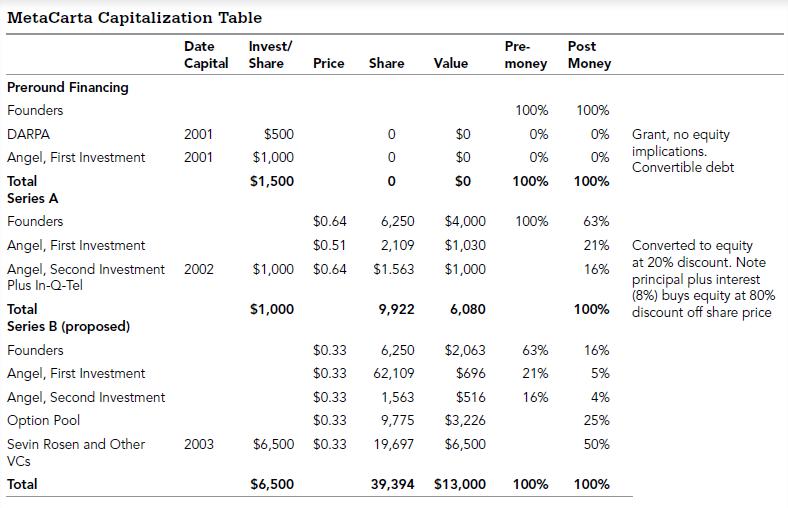

MetaCarta and the angel investors reached a compromise that is common for early‐stage investments: convertible debt.

In the fourth quarter of 2001, the investors contributed \($1\) million with an 8% accruing interest rate.

The debt was convertible at a discount to the next round or at a fixed valuation, which was \($4\) million in eighteen months. We figured that if we made it to that date, then we would be successful enough to be worth this valuation. The first money we raised was in the fourth quarter of 2001.

It converted in 2003.

Therefore, if MetaCarta did not raise any additional capital before November 1, 2003, then the company would be valued at \($4\) million before the angel investment of \($1\) million of debt was converted to equity. With the \($4\) million “pre‐money” valuation (value before the additional equity investment is added) and the original \($1\) million, the company’s post‐money valuation would be \($5\) million at the conversion. This would give the angel investors 20% ownership of the company, if MetaCarta did not raise a venture capital round of investment before that conversion.

The second qualifying event in the contract was a venture capital round of funding. If MetaCarta were to raise a venture capital round of financing, then the \($1\) million initial investment plus any accrued interest would convert to stock at a 20% discount to the price paid by the venture capitalists. Convertible debt allows the next round of investors to set the price and the valuation, but makes sure that the first investors receive a benefit for taking the increased risk of investing earlier.

Going Back for More

Although the company had sold their product to several government customers at this point, like many start‐ups, the cash burn rate was faster than expected. Product development was proceeding briskly but to keep on track, MetaCarta needed more money. In the second quarter of 2002, MetaCarta founders approached the task of finding more growth capital from two directions. First, they contacted the company’s existing angel investors. These individuals had not been anticipating the next round of financing until 2003. Nonetheless, the MetaCarta executive team had found its angel investors primarily from successful professionals from the software and technology communities in Boston and New York. Not only were these investors more open to initial investment in a software start‐up, but given the company’s success to date, the experienced investors understood the requirements to keep MetaCarta growing. Whereas investors who were only familiar with more traditional businesses may have balked at the idea of MetaCarta asking for additional angel funding, the technology‐minded financiers of this company did not shy away. The company raised a second angel round in 2002 from its original investors.

The second direction for raising capital was much more arduous. In‐Q‐Tel is the venture arm of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Based on MetaCarta’s product’s potential for government use, the founders approached In‐Q‐Tel.

In‐Q‐Tel is a very interesting source of capital. They are the venture arm of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). They were very prestigious in that the government customer base that we were focusing on views companies that receive money from In‐Q‐Tel as vetted technologies. From a technology perspective, having due diligence done by them was second to none. So, we spent a long time talking with them, showing them what we had, and convincing them to take a look.

They took a look and they liked what they saw. Once we got their seal of approval that the technology that we had was exceptional, they agreed to invest. There was a bunch of nuances around what they received for their investment…. We structured the deal such that it was very good for both of us….

The company was now two years old, In‐Q‐Tel had come in in a significant way, we had the DARPA funding, the angel backing, and customers that were really positive on us.

In‐Q‐Tel’s backing was really important. We were able to “wave that flag.” We were able to say that we had hit all these milestones that we had said that we were going to hit. We were able to walk into any meeting and say that we had taken money from In‐Q‐Tel and that they had already vetted the technology. Here is the name of the person to go talk to. He was part of the CIA. It was the best possible seal of approval. It was a lot of work to get it. We had been pursuing them for long time. It was early 2001 when we started [talking to In‐Q‐Tel] and took us a year and a half until they invested. And we were actively pursuing them for that whole time.

And More Money

Although happy about the product development and growth in customers, Doug could not believe how fast they were burning capital. Alas, another year later and MetaCarta was in need of more capital. Based on the success of previous fundraising and the increasing traction with customers, several venture capital firms expressed interest, but the fundraising environment in 2003 was still tight. Sevin Rosen Funds, one of the leading VC firms in the country with such notable investments as Compaq, Ciena, and Electronic Arts, was very interested. Considering that Sevin Rosen was in Texas and the Silicon Valley, Kevin Jacques, a venture partner at Sevin Rosen, enlisted a Boston firm to also participate, Solstice Capital. After several months, Kevin Jacques put an offer on the table. Sevin Rosen and a syndicate of other venture firms would invest \($6.5\) million into MetaCarta at a pre‐money valuation of \($6.5\) million. Doug, John, and Erik realized that would require 50% of the equity and give the investors the majority of the shares. The venture syndicate also wanted to include an option pool to entice future hires and reward strong performance from the existing employees. While Doug, John, and Erik agreed that an option pool was necessary and understood that they too would be eligible for option grants, they also realized that this would further dilute their current equity. As is common, the VCs wanted the shares to come out of the founders’ and earlier round investors’ stakes. Doug recounted:

The \($6.5\) pre‐money valuation resulted in a cram down to the angels, which was unfortunate. We were upset that our early backers were being offered a lower share price than they paid. Also, we as founders were struggling with the amount of dilution, grappling with the notion that although the piece may have been smaller, the potential size of the pie was now much bigger.

The following table shows MetaCarta’s capitalization over time, assuming they would take the Sevin Rosen money. The co‐founders debated. Should we take the money? The impact on our ownership and that of the previous investors is pretty severe. They also questioned whether the short‐term hit on the value of the investors and on themselves would be erased by the growth that the new capital would enable. MetaCarta could seek different venture capital sources, but the process between the initial meeting and closing the deal was likely to take months, and the outcome might very well be the same, especially if economic conditions worsened. What should they do? The co‐founders decided to sleep on it and decide in the morning.

Discussion Questions

1. Why has this deal attracted venture capital?

2. Should MetaCarta take the Sevin Rosen offer?

3. How was the valuation determined? Is there anything Meta-Carta could do to improve the valuation?

4. What would you, as an angel investor think about the current terms? What, if anything can you do about it?

Step by Step Answer: