News flash: American workers arent happy with rec-room ping-pong tables and free massages. Or, to be a

Question:

News flash: American workers aren’t happy with rec-room ping-pong tables and free massages. Or, to be a little more precise: Such perks aren’t enough to make them satisfied with their jobs. According to Gallup’s most recent State of the American Workplace Report, a mere 34 percent of U.S. workers are “engaged” in their work. That’s up from 30 percent from 2018, but it doesn’t amount to much, especially when you consider that more than half of all workers (52 percent) show up every morning but have very little interest in what they do all day. What’s worse, the 13 percent that’s left are actively disengaged—which means, says Gallup CEO Jim Clifton, that “they roam the halls spreading discontent.” According to the report, those actively disengaged employees cost the U.S. economy $550 billion a year in lost productivity.

Admittedly, younger workers tend to find workplace perks, such as Google’s nap pods and onsite roller-hockey rink, more attractive than their older counterparts. “They’re often looking for things they can brag about to their peers,” explains Bob Nelson, author of 1,501 Ways to Reward Employees. But if the boss is a jerk or tasks aren’t stimulating, cautions Nelson, “perks aren’t going to fix it. You may keep [younger workers] for a while, but at some point, they’re going to leave.”

Nelson’s opinion would seem to be confirmed by another major survey. According to The Conference Board’s most recent report on job satisfaction, while satisfaction among workers age 25–34 came in at 50.5 percent, only 37.8 percent of workers under age 25 were satisfied with their jobs—down from 46 percent in 2012 and about 60 percent 20 years earlier. Baby Boomers, observes The Conference Board’s Linda Barrington, “will compose a quarter of the U.S. workforce [by 2024], and since 1987 we’ve watched them increasingly losing faith in the workplace.” Nelson reports that younger workers tend to leave jobs after about a year, compared to 4.4 years for older employees, and John Gibbons, another Conference Board researcher, notes that 22 percent of all respondents to the survey don’t expect to be in their current jobs for more than a year. “These data,” he concludes, “throw up a red flag because widespread job dissatisfaction” and the resulting turnover “can impact enterprise-level success.” Recent studies indicate, for example, that it can cost an employer from 16 percent to 213 percent of average annual salary to replace every employee who leaves a company.

How do workers become dissatisfied, and what happens when they do? Danielle Lee Novack of Penn State University has created an instructive scenario that we’ve simplified to fit the needs of our case:

A woman named Megan has coordinated the onstage portions of dance competitions for three years. From January through June, Megan has to travel to different competition venues, including three weekends per month. This demanding half year is offset by the other six-month period, when her schedule is much more relaxed. Because she likes what she does, she’s willing to deal with the unusual schedule, especially as her manager has assured her that, should something important come up on a weekend, she’ll try to accommodate Megan. Her manager has recognized her excellent work in each of her three years, and Megan is satisfied with her job responsibilities, coworkers, and salary.

Megan learns in December that her best friend is getting married in June and asks her boss for the wedding weekend off. Despite her promises, her manager refuses to accommodate Megan. Needless to say, Megan is frustrated. As it happens, she’s also bothered by her manager’s tendency to micromanage subordinates and feels that she has no freedom to make any key decisions on her own. Besides, everything has to be approved before Megan can act on any of her own initiatives—a situation that’s already cost her two promotional partnerships that she’d worked personally to develop. Not only did she receive no recognition for her efforts, but she missed out on two bonuses. Finally, because the company is small and Megan already works directly under a high-ranking manager, she feels that there’s no chance for her to advance or take on new responsibilities in the future.

Before long, Megan is resentful about giving up weekends, about her manager’s habit of controlling every aspect of every project, and about the feeling that there’s little point in trying to excel if she’s merely going to be doing the same thing over and over again. In short, Megan is dissatisfied with her job, and she’s thinking about finding another one.

A review of both surveys shows that the sources of Megan’s dissatisfaction are pretty much the same as those cited by most dissatisfied American workers. At first glance, for example, some people may find it surprising that her pay doesn’t figure into Megan’s current discontent, but The Conference Board survey found that employees are slightly happier with pay scales than they have been in the past.

Not everybody, however, is equally “satisfied” with his or her income. Not surprisingly, The Conference Board says that 64 percent of people earning more than $125,000 are satisfied with their jobs, as are 57.6 percent of those with income between $75,000 and $100,000. However, only 24.4 percent of those earning under $15,000 could say the same thing. In the shrinking middle—where Megan no doubt falls—only 32 percent of those making $15,000–35,000 and 45 percent of those making $35,000–75,000 are satisfied

Danielle Kurtzleben, however, a former business and economics reporter for U.S. News and World Report, observes a contradiction between two survey findings: (1) that “growth in employee compensation has fallen off sharply since the 1980s and 1990s”; and (2) that workers are “not much less satisfied today with their wages than they were 25 years ago.” Workers, she cautions, may be more satisfied with wages than with total compensation, noting that the deepest levels of dissatisfaction between 1987 and 2013 is in such compensation-related areas as health coverage and sickleave policies

In fact, worker satisfaction with compensation plans are at a ten-year low—primarily because such compensation benefits as pension, 401(k), and health plans are fast disappearing. “For the most part,” says The Conference Board’s Rebecca Ray, “the employer contract is dead.” It’s a serious matter, she adds, because such benefits have long served to cement long-term employer–employee relationships

So, according to the Gallup and Conference Board reports, what aspects of their jobs are most workers most dissatisfied with? As it happens, the two areas that received the lowest scores are consistent, whether directly or indirectly, with the sources of Megan’s dissatisfaction: According to The Conference Board, only 23.8 percent of workers are satisfied with their employers’ promotion policies and only 24.2 percent with their bonus plans. Conversely, the most important drivers of satisfaction include growth potential, recognition, and satisfaction with one’s supervisor. It may also be interesting to note that although such areas as promotion policies and bonus plans are typically more important to men, women are significantly less satisfied than men on both counts.

At bottom, the results of both surveys are somewhat paradoxical—and perhaps even misleading. The apparent good news is that, at 47.7 percent, overall job satisfaction in 2013 was up from 47.3 percent in 2012. Obviously that’s very little, and the bad news is that both figures are meaningful only in the context of a 42.6 percent level in 2010—the lowest level ever. The worse news is that recent levels of job satisfaction represent a significant drop from 61.1 percent in 1987, the first year in which The Conference Board began tracking the phenomenon.

Case Questions

1. What about you? If you’re employed, are you (relatively) satisfied or dissatisfied with your job? If you’re not working (or haven’t yet held down a job), focus on the areas in which you’re satisfied or dissatisfied with what you are doing (e.g., going to school).

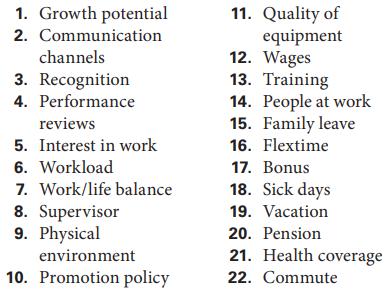

2. Next is a table listing 22 factors in job satisfaction in order of importance to the U.S. workers surveyed by The Conference Board. Create your own list of factors in order of their importance to you at this stage of your life. Be prepared to discuss the differences between your list and (1) the list below and (2) the lists drawn up by various classmates

3. What about Megan? First, draw up a list of job-dissatisfaction factors for Megan. Second, regard the following as applicable to Megan’s situation:

• She likes the type of work she does and has good relationships with coworkers.

• More than a few of her coworkers are also frustrated by the company’s tight supervision and demanding work schedule.

• She is a cheerful and positive person.

• She performs well and gets positive feedback because she looks for solutions to problems rather than dwelling on the negative aspects of things.

What do you think Megan should do? If you think that she should find another job, be prepared to explain why you think it’s the best move. If you think that she should try to resolve her frustrations before looking for another job, explain the points that she should try to get across in conversations with her boss.

Gad Levanon, an economist who coauthored The Conference Board report, makes this observation: “Based on macro trends worker satisfaction should be on the rise. But job dissatisfaction may remain entrenched until we see improvements in worker compensation, which has grown abysmally in recent years despite historically high corporate profits.” Levanon is expressing an opinion and making a related prediction. Explain his opinion and his prediction in your own words. Do you agree or disagree with this opinion and prediction? In particular, do you expect things to get better economically? Whether you answer yes or no, how do you see your prospects for getting a job that you’re satisfied with?

Step by Step Answer: