Design of Management Control System; Review of Chapters 22 and 23 Western Pants, Inc., is one of

Question:

Design of Management Control System; Review of Chapters 22 and 23 Western Pants, Inc., is one of America’s oldest clothing firms. Founded in the midnineteenth century, the firm weathered lean years and depression largely as the result of the market durability of its dominant, and at times only, product—

blue denim jeans. Until as recently as 1950, the firm had never seriously marketed other products or even additional types of trousers. A significant change in marketing strategy in the 1950s altered that course, which had been revered for 100 years by Western’s management. Aggressive new management decided at that time that Western’s well-established name could and should be used to market other lines of pants. Initial offerings in a men’s casual trouser were well received. Production in different patterns of this basic style continued, and stylish, tailored variations of the same casual motif were introduced almost yearly.

Alert planning in the early 1960s enabled Western to become the first pants manufacturer to establish itself in the revolutionary “wash and wear”

field. Further refinement of this process broadened the weave and fabric types that could be tailored into fashionable trousers and still survive enough machine washings and dryings to satisfy Western’s rigid quality-control standards.

With the advent of “mod” clothing and the generally casual yet stylish garb that became acceptable attire at semiformal affairs, pants became fashion items, rather than the mere clothing staples they had been in years past.

Western quickly gained a foothold in the bell-bottom and flare market, and from there grew with the “leg look” to its present position as the free world’s largest clothing manufacturer.

Today Western, in addition to its still remarkably popular blue denim jeans, offers a complete line of casual trousers, an extensive array of “dress and fashion jeans” for both men and boys, and a complete line of pants for women.

Last year the firm sold approximately 30 million pairs of pants.

Production For the last twenty years, Western Pants has been in a somewhat unusual and enviable market position. In each of those years it has sold virtually all its production and often had to begin rationing its wares to established customers or refusing orders from new customers as early as six months prior to the close of the production year. Whereas most business ventures face limited demand and, in the long run, excess production, Western, whose sales have doubled each five years during that twenty-year period, has had to face excess and growing demand with limited—although rapidly growing—production. The firm has developed 25 plants in its 150-year history. These production units vary somewhat in output capacity, but the average is roughly 20,000 pairs of trousers per week. With the exception of two or three plants that usually produce only the blue denim jeans during the entire production year, Western’s plants produce various pants types for all of Western’s departments. The firm has for some years augmented its own productive capacity by contractual agreements with independent manufacturers of pants. At the present time, there are nearly 20 such contractors producing all lines of Western’s pants (including the blue jeans). Last year contractors produced about one-third of the total volume in units sold by Western.

Tom Wicks, the Western vice-president for production and operations, commented on the firm’s use of contractors. “The majority of these outfits have been with us for some time—five years or more. Five or ten of them have served Western efficiently and reliably for over 30 years. There are, of course, a lot of recent additions. We’ve been trying to beef up our output, because sales have been growing so rapidly. It’s tough to tell a store like Macy’s halfway through the year that you can’t fill all their orders. In our eagerness to get the pants made, we understandably hook up with some independents who don’t know what they’re doing and are forced to fold their operations after a year or so because their costs are too high. Usually we can tell from an independent’s experience and per-unit contract price whether or not he’s going to be able to make it in pants production.

“Contract agreements with independents are made by me and my staff.

The word has been around for some years that we need more production, so we haven’t found it necessary to solicit contractors. Negotiations usually start either when an interested independent comes to us, or when a salesman or product manager interests an independent and brings him in. These product managers are always looking for ways to increase production! Negotiations don’t necessarily take very long. There are some incidentals that have to be worked out, but the real issue is the price per unit the independent requires us to pay him. The ceiling we are willing to pay for each type of pants is pretty well established by now. If a contractor impresses us as both reliable and capable of turning out quality pants, we will pay him that ceiling. If we aren’t sure, we might bid a little below that ceiling for the first year or two, until he has proven himself. Nonetheless, ’'m only talking here about a few cents at most. We don’t want to squeeze a new contractor’s margins so much that we are responsible for forcing him out of business. It is most definitely to our advantage if the independent continues to turn out quality pants for us indefinitely. Initial contracts are for two years. The time spans lengthen as our relationship with the independent matures.”

Mr. Wicks noted that the start-up time for a new contractor can often be as short as one year. The failure rate of the tailoring industry is quite high;

hence, new entrepreneurs can often walk in and assume control of existing facilities.

The Control System

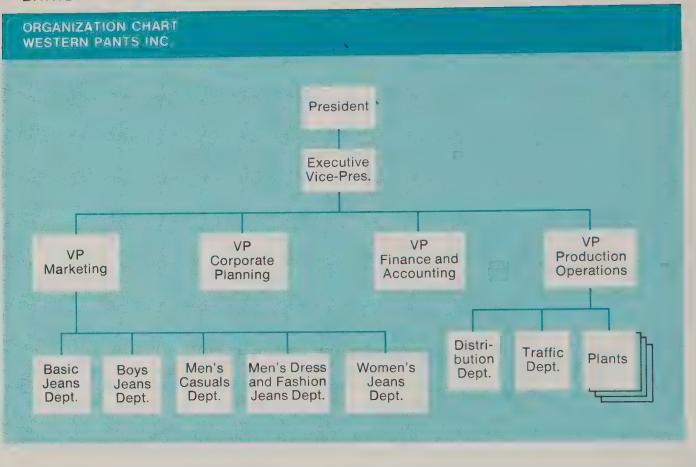

“We treat all our plants pretty much as cost centers [See Exhibit 23-1],”

Mr. Wicks continued. “Of course, we exercise no control whatever over the contractors. We just pay them the agreed price per pair of pants. Our own operations at each plant have been examined thoroughly by industrial engi-

neers. You know, time-motion studies and all. We’ve updated this information consistently for over ten years. ’m quite proud of the way we've been able to tie our standard hours down. We’ve even been able over the years to develop learning curves that tell us how long it will take production of a given type of pants to reach the standard allowed hours per unit after initial start-up or a product switchover. We even know the rate at which total production time per unit reaches standard for every basic style of pants that Western makes!

“We use this information for budgeting a plant’s costs. The marketing staff figures out how many pants of each type it wants produced each year and passes that information onto us. We divvy the total production up among plants pretty much by eyeballing the total amounts for each type of pants. We like to put one plant to work for a whole year on one type of pants, if that’s possible. It saves time losses from start-ups and changeovers. We can sell all we make, you know, so we like to keep plants working at peak efficiency. Unfortunately, marketing always manages to come up with a lot of midyear changes, so this objective winds up like a lot of other good intentions in life. You know what they say about the road to Hell! Anyhow, it’s still a game plan we like to stick to, and two or three plants making the basic blue jeans accomplish it every year.

“The budgeting operation begins with me and my staff determining what a plant’s quota for each month should be for one year ahead of time. We do this mostly by looking at what past performance at a plant has been. Of course, we add a little to this. We expect people to improve around here. These yearly budgets are updated at the end of each month in the light of the previous month’s production. Budget figures, incidentally, are in units of production. If a plant manager beats this budget figure, we feel he’s done well. If he can’t meet the quota, his people haven’t been working at what the engineers feel is a very reasonable level of speed and efficiency. Or possibly absenteeism, a big problem in all our plants, has been excessively high. Or turnover, another big problem, has been unacceptably high. At any rate, when the quota hasn’t been made, we want to know why, and we want to get the problem corrected as quickly as possible.

“Given the number of pants that a plant actually produces in a month, we can determine, by using the standards I was boasting about earlier, the number of labor hours each operation should have accumulated during the month. We measure this figure against the hours we actually paid for to determine how a plant performed as a cost center. As you might guess, we don’t like to see unfavorable variances here any more than in a plant manager’s performance against quota.

“We watch the plant performance figures monthly. If a plant manager meets his quota and his cost variances are OK, we let him know that we are pleased. I almost always call them myself and relay my satisfaction, or, if they haven’t done well, my concern. I think this kind of prompt feedback is important.

“We also look for other things in evaluating a plant manager. Have his community relations been good? Are his people happy? The family that owns almost all of Western’s stock is very concerned about that.”

A Christmas bonus constitutes the meat of Western’s reward system.

Mr. Wicks and his two chief assistants subjectively rate a plant manager’s performance for the year on a one-to-five scale. Western’s top management at the close of each year determines a bonus base by evaluating the firm’s overall performance and profits for the year. That bonus base has recently been as high as $3,000. The performance rating for each member of Western’s management cadre is multiplied by this bonus base to determine a given manager’s bonus.

Western’s management group includes many finance and marketing specialists. The casewriter noted that these personnel, who are located at the corporate headquarters, were consistently awarded higher ratings by their supervisors than were plant managers. This difference consistently approached a full point. Last year the average rating in the corporate headquarters was 3.85; the average for plant managers was 2.92.

Evaluation of the System Mia Packard, a recent valedictorian of a business school, gave some informed opinions regarding Western’s production operation and its management control procedures.

“Mr. Wicks is one of the nicest men I’ve ever met, and a very intelligent businessman. But I really don’t think that the system he uses to evaluate his plant managers is good for the firm as a whole. I made a plant visit not long ago as part of my company orientation program, and I accidently discovered that the plant manager ‘hoarded’ some of the pants produced over quota in good months to protect himself against future production deficiencies. That plant manager was really upset that I stumbled onto his storehouse. He insisted that all the other managers did the same thing and begged me not to tell Mr. Wicks. This seems like precisely the wrong kind of behavior in a firm that usually has to turn away orders! Yet I believe the quota system that is one of Western’s tools for evaluating plant performance encourages this type of behavior. I don’t think I could prove this, but I suspect that most plant managers aren’t really pushing for maximum production. If they do increase output, their quotas are going to go up, and yet they won’t receive any immediate monetary rewards to compensate for the increase in their responsibilities or requirements. If I were a plant manager, I wouldn’t want my production exceeding quota until the end of the year.

“Also, Mr. Wicks came up to the vice-presidency through the ranks. He was a plant manager himself once—a very good plant manager. But he has a tendency to feel that everyone should run a plant the way he did. For example, in Mr. Wicks’ plant there were eleven workers for every supervisor or member of the office and administrative staff. Since then, Mr. Wicks has elevated this supervision ratio of 11:1 to some sort of sacred index of leadership efficiency. All plant managers shoot for it, and as a result, usually understaff their offices. As a result, we can’t get timely and accurate reports from plants.

There simply aren’t enough people in the offices out there to generate the information we desperately need when we need it!

“Another thing—some of the plants have been built in the last five years or so and have much newer equipment, yet there’s no difference in the standard hours determined in these plants than the older ones. This puts the managers of older plants at a terrific disadvantage. Their sewing machines break down more often, require maintenance, and probably aren’t as easy to work with.”

Evaluate the management control system used for Western’s plants. What changes should be given serious consideration?

Step by Step Answer: