The evidence is derived from research at the plant in 1995 and 1997. The first study covered

Question:

The evidence is derived from research at the plant in 1995 and 1997. The first study covered interviews with all levels of employee and a questionnaire survey of shop-floor workers. In 1997, we revisited the plant and interviewed many of our key informants again.

The Lynemouth Smelter in 1990

Aluminium is a long-term, capital-intensive business. Some of Alcan’s Canadian smelters were built in the 1940s and were still in production in the 1990s. Lynemouth began production in 1972. Its basic operating design was established when the plant was built and this is largely fixed. There are three plants on site. The carbon plant manufactures anodes by mixing and baking carbon to form large blocks. These are taken to the pot rooms where they are placed in large crucibles (‘pots’). In these an electric current is passed through alumina to produce molten aluminium. This is then tapped and taken to the casting plant where it is cast into ingots. A major cost of production is energy.

Lynemouth is coal fired, and its costs are thus greater than its counterparts in Alcan’s main base of Quebec, where there is abundant hydroelectric power. Smelting is a continuous process, operating 24 hours per day, all year round. From its inception the plant ran on a system of 12-hour shifts. Workers divide their time between working ‘on-line’

servicing the pots, and rest periods spent off-line in the rest room. These rest breaks may take up several hours in any one shift.

In 1990, the plant employed 780 employees. Many workers had been with the plant since it opened. All shop-floor and craft workers were male, a few women were employed in clerical posts. Wages were good in relation to those of the locality, where unemployment was high and many jobs in manufacturing and heavy industry were lost during the 1980s.

Labour turnover was therefore low. Work organisation was fairly conventional, with each group of workers being responsible to a supervisor who dealt with all day-to-day production matters such as the allocation of tasks, granting of holidays and shift rotas.

Supervisors worked the same shifts as their work crews. The majority of workers were production operatives and craft workers, virtually all of whom belonged to trade unions. Production workers belonged to the GMB union which was numerically predominant and which had a full-time ‘convenor’

(a senior shop steward, elected by the stewards’

committee but paid by management).

Unions were also recognised by management in respect of white-collar staff, although membership levels were lower and influence was weaker.

The climate of industrial relations could be characterised as suspicious and mistrustful but not openly antagonistic. On the positive side, the plant appears to have had few serious strikes.

Among craft workers, multiskilling was established from 1972 so that, apart from a basic division between electrical and mechanical trades, there were no notable demarcations between different trades. This feature distinguished the plant from many manufacturing sites in the UK at the time.

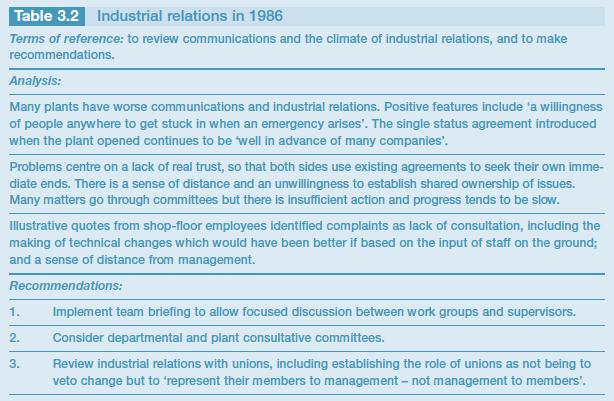

On the negative side, there was a wide-spread perception that it was hard to implement change and that communication was poor. This picture can be amplified by reference to Table 3.2, which is a summary of the conclusions of a study carried out in 1986, at the request of management and all the unions, by Peter Musgrave of the Industrial Society.

Table 3.2:

The underlying message was that management wanted to impose change by insisting on the application of parts of existing agreements, rather than involving the unions. For their part the unions saw negotiations in the light of their own sectional interests and employees reported a lack of consultation by management. This contributed to a growing sense of worker dissatisfaction, which was adversely affecting the quality of production. The report recommended the use of consultative committees and team briefing, and that management develop more cooperative relations with trade unions. There was, however, little action on the report’s recommendations.............

Questions

In analysing this case study you should address the following questions:

1. How would you describe Alcan’s management style? How would you describe the role and status of the HR function in Alcan? How did these factors affect the company’s decisions in relation to teamworking?

2. What were the main conditions encouraging the choice of teamwork in 1990 rather than one of the other possible options? Was this a good choice in light of their business strategy and competitive position? How typical do you think that Lynemouth was of management approaches in the UK?

3. Why do you think that it took until 1990 for teams to be used, when some of the conditions for them (notably a technical organisation of work around crews) had been in existence for many years? What does this tell us about how keen managements generally are to give workers autonomy? How far were teams ‘empowered’ and what were the limits to their autonomy?

4. What, if anything, would you do to tackle white-collar disaffection? How far do you believe that teamwork has ‘stalled’? What might be done to reinvigorate it?

Step by Step Answer:

Human Resource Management A Case Study Approach

ISBN: 9781843981657

1st Edition

Authors: Michael Müller-Camen, Richard Croucher, Susan Rosemary Leigh