Case Study What Role for Gold? Gold was at the center of the international monetary system during

Question:

Case Study What Role for Gold?

Gold was at the center of the international monetary system during the gold standard.

Individuals had the right to obtain or sell gold (in exchange for national currency) with the country’s central bank at the fixed official gold price.

Gold was also an important part of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates. The U.S.

government was expected to buy or sell gold with foreign central banks (but not with individuals)

at the official U.S. dollar price of gold.

What is the role for gold now? Gold remains an official reserve asset, but currently central banks make almost no official use of gold. Gold is also held by private individuals as part of their investments. Let’s look at both the official role and private role for gold more closely.

OFFICIAL ROLE: THE ONCE AND FUTURE KING?

You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

William Jennings Bryan, U.S. presidential candidate, 1896 Most observers of the current system are comfortable with the lack of a role for gold in official international activity. Indeed, some believe that central banks and the International Monetary Fund should sell off their current official holdings of gold. One reason to sell is that gold plays no active role and earns no interest. The part of national wealth (or IMF assets) held in gold could be invested more productively. Another reason is that the proceeds of gold sales could be used for assistance to the poorer countries of the world.

Central banks and the IMF have made gold sales into the private market in recent decades (a process called demonetization of gold ).

A small group of people are strong advocates of a return to a real gold standard in which countries tie their currencies to gold. These proponents believe that a return to a gold standard would greatly reduce national and average global rates of inflation by creating a strong discipline effect on countries’ abilities to expand their money supplies. They also believe that a return to a gold standard would eliminate the variability of exchange rates by establishing full confidence in the system and by enforcing monetary adjustments to achieve external balance. By creating stability and confidence in national moneys and exchange rates, they believe, the return to a gold standard would stabilize and lower both nominal and real interest rates.

Most international economists oppose a return to the gold standard. To most, a gold standard is not nearly as stabilizing as its proponents claim, except perhaps in the very long run. The supply of new gold to the world is governed not by some master regulator, but rather by mining activities. A major discovery of new minable gold deposits leads to a rapid expansion of the world gold supply. As central banks bought gold to defend the fixed gold prices, national money supplies would expand rapidly and inflation rates would increase. On the other hand, if there were no new discoveries, and if current mines slowed output as mines were exhausted (or if major strikes or similar disruptions slowed output), national central banks would have to sell gold to defend their price (assuming that private demand continued to grow). National money supplies would shrink and countries would enter into painful deflations

(with weak economic conditions forcing general price levels lower).

Looking at the other side of the market for gold, decreases in private demand for gold would require central banks to buy gold to defend their price, expanding money supplies. Increases in private demand would force central banks to sell gold, shrinking national money supplies.

Supply swings were evident even during the classical gold standard. Between 1873 and 1896, the British price level fell by about one-third, and it then inflated back up from 1896 to 1913. These shifts were closely related to changes in the growth rates of world stocks of monetary gold, and these were closely related to cycles in mining driven by gold discoveries.

Between 1850 and 1873, the world gold stock grew by 2.9 percent per year, with discoveries leading to mining booms in California and Australia. This permitted money supplies to keep up with the growing real demand for money, so that price levels remained about steady. Between 1873 and 1896, the world gold stock grew by only 1.7 percent per year. This was not enough to keep up with continued growth in real money demand, and the general price level was forced down. Then from 1896 to 1913, new discoveries of gold led to mining booms in the Klondike (Canada) and the Transvaal (South Africa). The world gold stock rose 3.2 percent per year, faster than real money demand was growing, so the general price level increased. With such fluctuations in the growth of monetary gold, it is difficult to claim that the gold standard ensured steady expansion of the world money base (although the gold standard did limit money growth and inflation in the long run).

Because a gold standard probably would not be nearly as stable as its proponents claim, most international economists oppose a return to a gold standard. Bolstering their belief are the more typical arguments about the advantages of flexible or floating exchange rates, including independence in choosing priorities and using policies. In addition, the resource costs of expanding official gold reserves are themselves high. New gold must be mined. This seems to be an inefficient use of resources, to produce something that will largely sit in the vaults of central banks.

PRIVATE ROLE: A SOUND INVESTMENT?

The official link between gold and currencies effectively ended in 1968, and it seems unlikely to be revived. Even though its official role has largely ended, should gold play a role in the investments of private individuals? Holding gold pays no interest, so the return to gold comes from increases in its price. (The return earned is actually lower than the price increase suggests because of the costs of buying and selling as well as the costs of storing and safekeeping.)

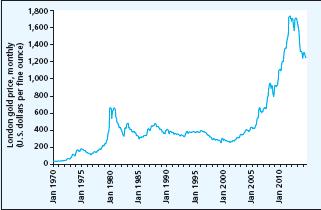

The accompanying graph shows the monthly dollar price of gold since 1970. There are three lessons from this graph. First, anyone who bought gold in the early 1970s earned a high rate of return through 1980, as the dollar price increased from under $100 per ounce to over $600 per ounce. Similarly, anyone who bought in the early 2000s earned a high return, as the gold price rose from less than $300 to about $1,800 in September 2011. For each of these time periods, the gold-price increase far exceeded general price inflation or the rates of return available on most financial assets.

Second, anyone who bought and sold gold from the early 1980s to the early 2000s generally was disappointed. The gold price stayed in the range of $250 to $500 per ounce. The gold price did not keep up with general price inflation, and it underperformed compared to the returns available on many financial assets like stocks and bonds.

Third, far from being stable, or tracking general price inflation as an “inflation hedge,” the gold price has fluctuated a lot. It soared during 1979–1980, falling back during 1980–1982, rose strongly during 1982, and so forth.

Why has the price of gold jumped around so much during the past several decades? Shifts in supply have some impact, but major pressure often comes from shifts in demand. To a large extent gold is what frightened people invest in.

This part of demand increases and decreases as fears and tensions rise and subside.

Suppose you are wealthy and live in an unstable region of the world. Clandestine gold ownership can protect you from having your assets seized or heavily taxed. Or suppose you fear an explosion of inflation. Holding real assets like gold provides at least some protection against the loss of purchasing power that will afflict most

paper assets. Or suppose you are worried about financial and economic instability resulting from the global crisis that began in 2007, large fiscal deficits in the United States and Europe, the effects of quantitative easing by the Fed. You (and others) buy gold to move out of paper assets, and the price of gold rises rapidly.

Thus, private investments in gold are bets about the future course of gold prices. Over the long term the price of gold has roughly kept up with the rise of general prices (though past performance is no indicator of future performance).

But for any short- or medium-term period of time, gold’s value is anybody’s guess. For a commodity that symbolizes stability, unpredictable shifts in demand and supply can and do cause large swings in gold’s real price.

DISCUSSION QUESTION Would adoption of a new gold standard by the industrialized countries result in better achievement of internal balance for these countries?

Step by Step Answer: