It is widely suspected that immigrants are a fiscal burden, swelling the rolls of those receiving public

Question:

It is widely suspected that immigrants are a fiscal burden, swelling the rolls of those receiving public assistance, using public schools, and raising police costs more than they pay back in taxes. This suspicion was the basis for a U.S. law that made immigrants (both legal and illegal)

ineligible for some forms of public assistance.

This suspicion, applied to illegal immigrants, was the basis for citizens first in California, and later in Arizona, to vote to deny public services to immigrants whose papers are not in order.

Are immigrants a burden to native taxpayers?

The answer to this question is more complicated than it sounds, for two reasons:

• While some effects are easy to quantify using government data, other effects must be estimated without much guidance from available data.

• The full fiscal effects of a new immigrant occur over a long time—the immigrant’s remaining lifetime and the lives of her descendants.

Let’s look first at the effects of the set of immigrants that are in a country at a particular time. This kind of analysis provides a snapshot of the fiscal effects of immigrants during a year. We can see clearly what we can and cannot quantify well, but we do not see effects over lifetimes.

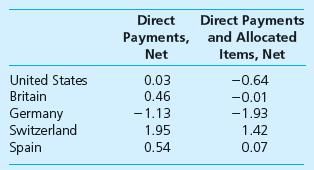

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2013, Chapter 3) examined the fiscal effects of immigrants in each of a number of countries during 2006–2008. Part of the analysis was relatively easy. The OECD researchers had good information on direct financial payments to and from the government. The immigrants’ payments to the government include income taxes and social security contributions. Government payments to the immigrants include public pensions and transfers for public assistance, unemployment and disability benefits, family and child benefits, and housing support. If these were all the fiscal effects of immigrants, then, in most countries examined, immigrants made a positive net fiscal contribution. The first column of the table shows the sizes of the net direct payments as a percent of GDP, for a few countries from the study. For Germany, the net effect of immigrants was negative because many immigrants in Germany are pensioners (Turks who arrived as guest workers in the 1960s and refugees from the former Soviet Union who arrived in the 1990s).

The remaining part is hard. Immigrants pay other kinds of taxes, including value added or sales taxes and, indirectly, corporate income taxes. And immigrants share in using all kinds of public services, including schools, medical care, training and labor market assistance, infrastructure, police, public administration, and defense.

How much does immigrants’ use of each of these items expand government spending on it? The answer varies by the type of service and immigrants’

use. Immigrants probably have almost no effect on national defense expenditures. (Indeed, they might add effective soldiers.) Immigrants’

use of education and health services probably does require additional government expenditures to maintain the same level of services to everyone else. Immigrants’ use of transport infrastructure, police services, and similar items may require some expansion of government expenditure on these items. The hard part is that there is no good way to know how much immigrants expand government expenditures on most of these items. To go further, we must make assumptions.

The OECD researchers made assumptions to allocate these items (excluding defense spending and interest on government debt), generally by using per person estimates of the items. The second column of the table shows the estimates for the net fiscal effects of both the direct payments and the allocated items. Based on the assumptions used by the researchers, the allocated items are net negative for most countries, including the five shown here. For the United States, the estimated net fiscal effect of its immigrants shifts from a positive contribution to a negative

“burden.” However, perhaps the most defensible conclusions are that, for most countries including the United States, the current fiscal effects of immigrants are challenging to measure and probably are relatively small.

Another way to look at the fiscal effects of immigrants is over their entire remaining lifetimes, and even to examine the fiscal effects of their descendants. For government programs that have costs for recipients of some ages but generate tax revenues from these same recipients at other ages, the lifetime approach is the more sensible way to calculate the fiscal effects of a small increase in immigration. One example is public schooling. Immigrants’ children increase the cost of providing public schooling. But the schooling increases the children’s future earnings, so the government eventually collects more taxes. Another example is social security. While working, immigrants pay social security taxes, but in the future they will collect social security payments.

Analysis of the fiscal effects of immigrants over lifetimes is complicated and requires many assumptions, including assumptions about how much immigrants add to costs as they consume various public services. Smith and Edmonston (1997, Chapter 7) examine the lifetime fiscal effects of typical immigrants in the United States as of 1996. Over the lifetime of the average immigrant (not including descendants), the net fiscal effect is slightly negative, about \($3\),000 net cost to native taxpayers. However, the effect depends strongly on how educated the immigrant is.

(Education is used as an indicator of earnings potential based on labor skill or human capital.)

• The average immigrant who did not complete high school imposes a lifetime net cost of \($89\),000.

• The average immigrant who is a high school graduate imposes a net fiscal cost of \($31\),000.

• The average immigrant who has at least one year of college provides a lifetime net fiscal benefit of \($105\),000.

These findings indicate that the fiscal effects of immigrants depend very much on the levels of labor skills of the immigrants. More-educated, more-skilled immigrants have higher earnings, resulting in larger payments of taxes. Immigrants with greater skills and higher earnings are also less likely to use public assistance.

In addition, Smith and Edmonston conclude that the descendants of the typical immigrant provide a net fiscal benefit of \($83\),000. Thus, the typical immigrant and her descendants provide a net fiscal benefit of \($80\),000 (5 2\($3\),000 1 \($83\),000). Interestingly, this net fiscal benefit is not spread evenly over government units. State and local governments bear a net fiscal cost of \($25\),000, while the U.S. federal government receives a net benefit of \($105\),000. * We can see a clear basis for tension between states and the federal government over immigration policies.

Especially, we can see the basis for California’s efforts to limit its outlays for immigrants because California has by far the largest proportion of immigrants of any state.

DISCUSSION QUESTION Immigrants, compared to natives in a country, tend to be young, to have lower wage rates, to be healthier, and to have more children. For fiscal effects for this country, how do these characteristics of immigrants matter?

* This differential is not unique to immigrants. The typical native-born child also imposes a net cost on state and local governments. They largely bear the costs of education, health care, and other transfers early in the child’s life, while the federal government collects most of taxes paid after the child grows up.

Step by Step Answer: