Sheila was frustrated. Although she was happy with both the topic and the constructs she had chosen

Question:

Sheila was frustrated. Although she was happy with both the topic and the constructs she had chosen to examine in her senior honors thesis, she had hit several roadblocks in determining what measures to use to assess each variable in her proposed study. Now that she had finally identified useful measures to include in her survey, she was concerned that her response rate would suffer because of the rather impressive length of the survey. Reasoning that individuals in the sample she hoped to use were unlikely to spend more than a few minutes voluntarily responding to a survey, Sheila considered her options. First, she could eliminate one or more variables. This would make her study simpler and would have the added benefit of reducing the length of the survey. Sheila rejected this option, however, because she felt each variable she had identified was necessary to adequately address her research questions. Second, she considered just mailing the survey to a larger number of people in order to get an adequate number to respond to the lengthy survey. Sheila quickly rejected this option as well. She certainly didn’t want to pay for the additional copying and mailing costs. She was also concerned that a lengthy survey would further reduce the possibility of obtaining a sample that was representative of the population. Perhaps those individuals who would not respond to a long survey would be very different from the actual respondents.

Suddenly a grin spread across Sheila’s face. “Couldn’t I shorten the survey by reducing the number of items used to assess some of the variables?” she thought. Some of the scales she had selected to measure variables were relatively short, while scales to measure other variables were quite long. Some of the scales were publisher-owned measures and thus copyrighted. Others were nonproprietary scales both created and used by researchers. Recognizing the reluctance of publishers to allow unnecessary changes to their scales, Sheila considered the nonproprietary measures. The scale intended to assess optimism was not only nonproprietary but also very long: 66 items. A scale assessing dogmatism was also nonproprietary and, at 50 items, also seemed long. Sheila quickly decided that these would be good scales to target for reduction of the number of items.

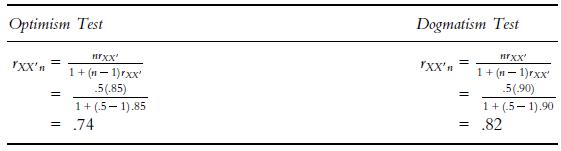

In class, Sheila had learned that the Spearman–Brown prophecy formula could be used to estimate the reliability of a scale if the scale was doubled in length. Her instructor also explained that the same formula could be used for either increasing or decreasing the number of items by a certain factor. Sheila knew from her research that the typical internal consistency reliability finding for her optimism scale was .85, and for the dogmatism scale it was .90. Because she wanted to reduce the number of items administered for each scale, she knew the resulting reliability estimates would be lower. But how much lower? Sheila considered reducing the number of items in both scales by one half. Because she was reducing the number of items, the number of times she was increasing the scale was equal to one half, or .5. She used this information to compute the Spearman–Brown reliability estimate as follows in Table 5.1:

Table 5.1

In considering these results, Sheila thought she’d be satisfied with an internal consistency reliability estimate of .82 for the dogmatism scale, but was concerned that too much error would be included in estimates of optimism if the internal consistency reliability estimate were merely .74.

In considering these results, Sheila thought she’d be satisfied with an internal consistency reliability estimate of .82 for the dogmatism scale, but was concerned that too much error would be included in estimates of optimism if the internal consistency reliability estimate were merely .74.

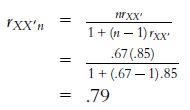

Undeterred, Sheila decided to estimate the reliability if only one-third of the optimism items were removed. If one-third of the items were dropped, two-thirds (or .67) of the original items would remain. Therefore, the Spearman–Brown prophecy estimate could be computed as follows:

Optimism Test

Sheila decided this reliability would be acceptable for her study. In order to compete her work, Sheila randomly selected 25 (50%) of the items from the dogmatism scale, and 44 (67%) of the items from the optimism scale. She was confident that although her survey form was now shorter, the reliability of the individual variables would be acceptable.

Questions

1. Do you think an rxx = .74 for the optimism scale would be acceptable or unacceptable for the purpose described above? Explain.

2. Should Sheila have randomly selected which items to keep and which to delete? What other options did she have?

3. How else might Sheila maintain her reliability levels yet still maintain (or increase) the number of usable responses she obtains?

4. Why do you think Sheila is using .80 as her lower acceptable bound for reliability?

Step by Step Answer:

Measurement Theory In Action

ISBN: 9780367192181

3rd Edition

Authors: Kenneth S Shultz, David Whitney, Michael J Zickar