I grew up in a small town outside Philadelphia and went to the local high school, where

Question:

I grew up in a small town outside Philadelphia and went to the local high school, where I ran track all four years. Our team practiced outdoors, and in the winter, in the bitter cold, the experience was pretty miserable. The school was set on a hill, and as we ran around the parking lot the wind would come whipping around the building and hit us. We had to watch our steps carefully so as not to slip and fall on the ice. While we were doing our laps, the coach—a 50-year-old named Jack Armstrong—would stand against one wall protected from the wind, bundled up in a huge coat and wool hat and gloves, clapping and smiling cheerfully. Every time the pack shuffled past, he’d shout, “Remember— you’ve got to make your deposits before you can make a withdrawal!” Now, this was a public school with no special facilities, and the team was made up of average athletes with differing levels of intelligence and motivation. But we never lost one single meet. And because of that success, and maybe because of the way in which the advice itself was delivered—I remember it when people yell at me— Coach Armstrong’s words resonated. I’ve thought of them a million times throughout my career in finance, and they’ve guided this firm, too.

Coach Armstrong came to mind in one of my first weeks on Wall Street, 35 years ago. I’d stayed up all night building a massive spreadsheet to be ready for a morning meeting. These were the days before Excel, and it was a huge feat for someone as bad at statistical stuff as I was to do this all by hand; I was pretty proud of myself. The partner on the deal, however, took one look at my work, spotted a tiny error, and went ballistic. As I sat there while he yelled at me, I realized I was getting the MBA version of Coach Armstrong’s words. Making an effort and meeting the deadline simply weren’t enough.

To put it in Coach Armstrong’s terms, it wasn’t sufficient to make some deposits; I had to be certain that the deposits would cover any withdrawal 100% before we made a decision or did a deal. If I hadn’t done all the up-front work and made completely sure that my analysis was correct, I shouldn’t have put anything forth. Inaccurate analysis produces faulty insights and bad decisions— which lead to losing a tremendous amount of money.

Today, whenever I’m under pressure to make a decision on a transaction but I don’t know what the right one is, I try desperately to postpone it. I’ll insist on more information—on doing extra laps around the intellectual parking lot—before committing. . . .Every year I speak to our new associates and give them this advice, although in my own words. This isn’t like school, I tell them, where you want to get your hand in the air and give an answer quickly. The only grade here is 100. Deadlines are important, but at Blackstone you can always get help in meeting them. As a firm, we can always figure out how to do another lap around the parking lot. Because what’s true when running track is true when doing deals: The person who’s the readiest for game day will be the one who wins.

Questions for Discussion

1. How would you describe Stephen Schwarzman’s personality?

2. Relative to the concepts you have just read about, what traits and characteristics would describe the “ideal” Blackstone job candidate? Explain your rationale for selecting each characteristic.

3. Ranked 1 = most important to 8 = least important, which of Gardner’s eight multiple intelligences are most critical to being successful at a major investment company like Blackstone? Explain your ranking.

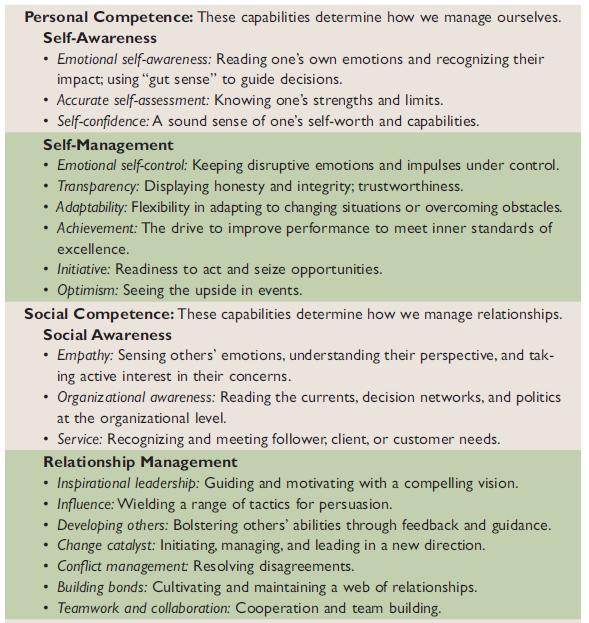

4. Using Table 5–5 as a guide, how important are the various emotional intelligence competencies for making good investment decisions? Explain.

Table 5-5

5. Do you have what it takes to work for someone like Stephen Schwarzman? Explain in terms of the concepts in this chapter.

Step by Step Answer: