Question: 1) Topics (200 words). This explains the chapters theme and its importance. 3 pts. 2) Analysis (600 words). Explain the pros and cons or identify

1) Topics (200 words). This explains the chapters theme and its importance. 3 pts.

2) Analysis (600 words). Explain the pros and cons or identify ambiguity & controversy.. 5 pts.

3) Application (400 words). Provide examples (with special reference to media & journalists whenever possible) 4 pts.

4) Your Input (300 words). This includes your reflection, understanding and evaluation of the subject. You may also mention difficulties encountered. I need you to write a report

PLS refer to the first page for understanding this is a book chapter report the pages below are from a book and the information you need is on the first page

.

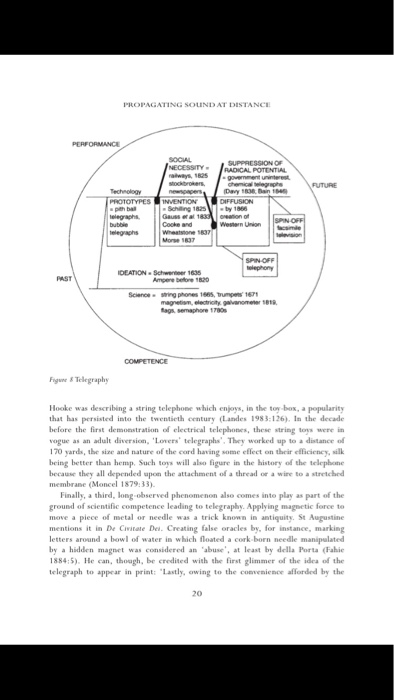

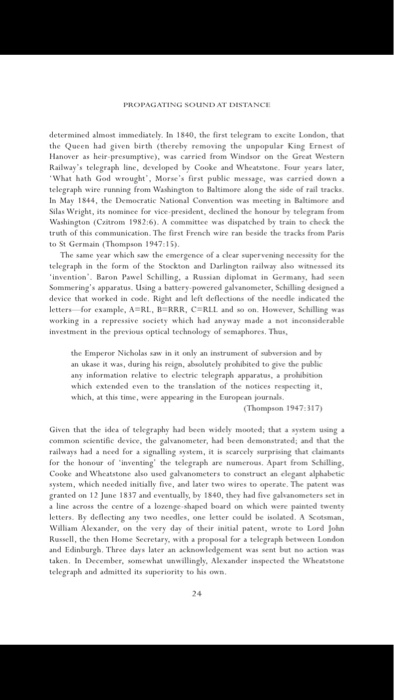

THETELEGRAPH SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE TO IDEATION: STATIC ELECTRICAL TELEGRAPHS The application of the natural phenomenon we call electricity to the processes of human communication involves a line of electrical experimenters stretching back to Queen Elizabeth I's physician William Gilbert. The first Englishman to write, in De Magnete, a book based on direct observation, Gilbert coined the phrase vis electrica to describe the property, noticed in antiquity, possessed by amber thatpov, and some other substances which, when rubbed, attracted light materials such as feathers, Further experimentation by the superintendent of the gardens of the King of France in 1733 revealed what Franklin was to call positive and negative charges. In 1745 Musschenbroek built the first device to produce an electric field, the Leyden Jar. His friend, Cunaeus, got a serious electric shock from it. The jar prompted the beginnings of a discussion as to the nature of the phenomenon and a parade of electricians, many of whose names are now immortalised in equipment or units of measure, elaborated, into the early nineteenth century, both the theory of and the laboratory apparatus for creating electrical phenomena. There is another, even older strand of observation also involved in the ground of scientific competence leading to electrical communications systems. Robert Hooke, the experimental physicist, wrote in 1665 I can assure the reader that I have, by the help of a distended wire, propagated the sound a very considerable distance in an instant, or with seemingly as quick a motion as that of light, at least incomparably quicker than that which at the same time was propagated through air; and this was not only in a straight line or direct, but in one bended in many angles (Moncel 1879:11-12) 19 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE FUTURE PERFORMANCE SOCIAL SUPPRESSION OF NECESSITY RADICAL POTENTIAL -government interest obrokers chomware Technology nowe DA WA han be PROTOTYPES INVENTION DIFFUSION 1-Schling 1821 - by 1806 elegraph Gauss at 183 creation of Cocked Western Union SPIN-OFF elegraphs Whatone 1807 Morse 1697 PAST SPIN OFF IDEATION - Schwerter 1656 lephony Ampere before 1820 Science string phones 1885, Trumpet 1671 magretion, clectricity galvanometer 1818. Tagssemaphore 17808 COMPETENCE Figure Telegraphy Hooke was describing a string telephone which enjoys, in the toy box, a popularity that has persisted into the twentieth century (Landes 1983:126). In the decade before the first demonstration of electrical telephones, these string toys were in vogue as an adult diversion, 'Lovers' telegraphs'. They worked up to a distance of 170 yards, the size and nature of the card having some effect on their efficiency, silk being better than hemp Such toys will also figure in the history of the telephone because they all depended upon the attachment of a thread or a wire to a stretched membrane (Moncel 1879:33). Finally, a third, long.observed phenomenon also comes into play as part of the ground of scientific competence leading to telegraphy. Applying magnetic force to move a piece of metal or needle was a trick known in antiquity. St Augustine mentions it in De Civitate Del. Creating false oracles by, for instance, marking letters around a bowl of water in which floated a cork born needle manipulated by a hidden magnet was considered an 'abuse, at least by della Porta (Fahie 1884:5). He can, though, be credited with the first glimmer of the idea of the telegraph to appear in print: "Lastly, owing to the convenience afforded by the 20 THE TELEGRAPH magnet, persons can converse together through long distances...we can communicate what we wish by means of two compass needles circumscribed with an alphabet' (ibid.). In 1635, Schwenteer, in his classements physico-mathematics describes a system using a magnetic needle along these lines, but the experiments which would demonstrate the viability of his idea were not to be conducted until 1819 (Braudel 1981434). The idea of using magnetism and electricity for a signalling system was thus established early in the modern period. The elaboration of the idea as well as the first prototypes for such systems tended to propose the use of static electricity. In one, suggested by an anonymous correspondent of the Scots" Magazine writing from Renfrew in 1753, signalling was to be effected by twenty-six wires with twenty-six electroscopes in the form of mounted pith balls, each to represent one letter Making the electrical circuit agitated the balls. This was the first of many such ideas, another, by Bozolus, a Jesuit, being explained in Latin verse Devices along these lines existed in experimental form by the 1780s. One of the brothers Chappe had begun his telecommunication experiments with thoughts of such a friction telegraph, before perfecting his optical-mechanical system, Optical mechanical systems, such as the Chappe semaphore, can be seen as a sort of precursor to the electrical telegraph, like the string telephones. They are part of the ground of competence rather than prototypes, Received opinion suggests that the supervening necessity for the semaphere was the needs of France's revolutionary armies. Patrice Flichy, however, goes further to point out that the Revolution itself required enhanced communication if the people were to act all over the vastness of France with one mind. The semaphore system was used for civilian communications, for example, decrees of the Convention and causes of the constitution as well as news of political events such as Bonaparte's coup d'tat were all signalled to provincial centres. Strasbourg could communicate with Paris in 36 minutes. Overall, the effect of the semaphore was to help create a new sort of mental landscape which Flichy terms, 'T'espace national". (Flichy 1991:19-23). In France, by the 1840s, there were over 3000 miles of semaphore lines, all operated by the War Department. A law of 1837 established a French government monopoly in long distance communication systems (Brock 1981:136). Lines of semaphore stations were established all over Europe. Nicholas I connected St Petersburg to Warsaw and the German border, with a branch to Moscow, by towers five to six miles apart, 220 towers each with six men. Pre-electric telegraphs, like any other technology, created a certain inertia, and research on electrical alternatives was inhibited. In fact, the existence of these claborate, military systems operated to suppress the efforts of a number of early experimenters working in the static electrical tradition. For example, one of the Wedgwoods, Ralph, planned an electrie telegraph for the benefit of the Admiralty in 1814 but was turned away. Their Lordships' lackeys wrote, "the war being at an end, 21 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE and money scarce, the old system fol shutter semaphores was sufficient for the country" (Fahie 1884:124; brackets in original). The shutter semaphore had been developed in an Admiralty competition by Lord George Murray to improve upon the French device. The inventor of the most elegant of these true electrical prototypes suffered a similar fate In 1816, Francis Ronalds demonstrated an electrical telegraph system that worked over eight miles of wire strung up on frames in his London garden. He mounted clock mechanisms at either end of the wire. In place of the clock hands he had an engraved disk with letters, numbers and other instructions inscribed and in place of the glass was an opaque disk in which an aperture was cut. The clocks being exactly synchronised, the operator waited for the required letter or instruction to appear in the aperture, made the circuit and moved the clectroscope, a pith ball at the other end of the wire. The receiver, seeing what letter was in the second clock's aperture as the ball moved, could note it down. Within two days of receiving notice of this apparatus, Barrow, the secretary of the Admiralty wrote: 'Mr. Barrow presents his compliments to Mr. Ronalds, and acquaints him, with reference to his note of the 3rd inst, that telegraphs of any kind are now wholly unnecessary, and that no other than the one now in use will be adopted' (Fabie 1884:124). Ronalds" is the classic rejected prototype. The last static electrical telegraph was proposed, a true redundancy, in 1873, forty-six years after the dynamie version was invented' Ronalds' experience does not so much reveal official blindness as a lack of supervening social necessity, the reason for such blindness. Ships had flags and armies (and governments) semaphores. They were accepted as partial precursors for the telegraph and they provided as much communication capacity as was required PROTOTYPES, NECESSITY AND 'INVENTION": DYNAMIC ELECTRICAL TELEGRAPHS Systems based on dynamic electricity were proposed in the first decade of the nineteenth century but these too required a discrete circuit for each letter of the alphabet. Instead of pith balls, the idea was to exploit the fact that water decomposes, giving off bubbles when electricity is introduced into it. Using a Voltaic pile and various arrangements of glass flasks, it was possible to indicate letters by these bubbles. The ideation of the modern telegraph had occurred in Schwenteer's suggestion but this was clearly forgotten; for, 175 years later, Ampere had the same sort of thought and proposed that one could by means of as many pairs of conducting wires and magnetic needles as there are letters' establish a signalling system. In 22 THE TELEGRAPH 1819, it was noticed that an electric current would deflect magnetic needles and Faraday discovered that a freely moving magnetised needle when surrounded by a wire coil will respond to the power of the electrical current in the coil. A device, the Galvanometer, to measure currents was built and the would be electrical telegraphers acquired a signalling instrument using dynamic electricity which was to disperse the bubbles and banish the pith balls. The prototype phase of telegraphy ended But there was still question: Who needed a dynamic electrical system for distant signalling? Where was the social necessity to turn these experiments into an 'invention? In 1809, Richard Trevithick brought to London the latest wonder of the country's mining areas, an iron wagon way upon which a steam locomotive ran At Euston Square he built around track within a wooden fence and charged 1 shilling for the ride (Briggs 1979,90). In 1825, the first passenger train to go anywhere ran between Stockton and Darlington. The railway age began somewhat ftfully, Between 1833 and 1843 money was raised to build 2300 miles of railway in the UK, about a quarter of which was constructed during that time (Dyos and Aldcroft 1974:124), Early railways were single-track affairs which necessitated, for the first time, instantaneous signalling methods. One of the many who can lay claim to having "invented the telegraph, Edward Davy, saw this clearly. In 1838 he wrote: The numerous accidents which have occurred on railways seem to call for a remedy of some kind; and when future improvements shall have augmented the speed of railway travelling to a velocity which cannot at present be deemed safe, then every aid which science can afford must be called in to promote this object. Now, there is a contrivance...by which, at every station along the railway line, it may be seen, by mere inspection of a dial, what is the exact situation of the engines running, either towards, or from, that station, and at what speeds they are travelling (Fabie 1884-407) Here then is a real and pressing supervening necessity railway safety. The history of telegraphy offers a clear example of how one technology, in this case the railways, creates a supervening necessity for another, the telegraph. Davy (who is not to be confused with Sir Humphry Davy of the miner's lamp) was eager to have the railway interests exploit the contrivance", a dynamic telegraph of his design. He did not bother the Admiralty and he was right not to. In fact, the earliest telegraph wires did indeed run beside railway tracks and were used for operational purposes. That they could also be used for other messages was 23 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE determined almost immediately. In 1840, the first telegram to excite London, that the Queen had given birth (thereby removing the unpopular King Ernest of Hanover as heir presumptive), was carried from Windsor on the Great Western Railway's telegraph line, developed by Cooke and Wheatstone. Four years later, What hath God wrought", Morse's first public message, was carried down telegraph wire running from Washington to Baltimore along the side of rail tracks In May 1844, the Democratic National Convention was meeting in Baltimore and Silas Wright, its nominee for vice-president, declined the honour by telegram from Washington (Critrom 1982:6). A committee was dispatched by train to check the truth of this communication. The first French wire ran beside the tracks from Paris to St Germain (Thompson 1947:15). The same year which saw the emergence of a clear supervening necessity for the telegraph in the form of the Stockton and Darlington railway also witnessed its 'invention'. Baron Pawel Schilling, a Russian diplomat in Germany, had seen Sommering's apparatus. Using a battery-powered galvanometer, Schilling designed a device that worked in code, Right and left deflections of the needle indicated the letters for example, A=RL, BERRR, CERLL and so on. However, Schilling was working in a repressive society which had anyway made a not inconsiderable investment in the previous optical technology of semaphores. Thus, the Emperor Nicholas saw in it only an instrument of subversion and by an ukase it was, during his reign, absolutely prohibited to give the public any information relative to electric telegraph apparatus, a prohibition which extended even to the translation of the notices respecting it, which, at this time, were appearing in the European Journals. (Thompson 1947:317) Given that the idea of telegraphy had been widely mooted that a system wing common scientific device, the galvanometer, had been demonstrated and that the railways had a need for a signalling system, it is scarcely surprising that claimants for the honour of inventing the telegraph are numerous. Apart from Schilling, Cooke and Wheatstone lowed galvanometers to construct an elegant alphabetic system, which needed initially five, and later two wires to operate. The patent was granted on 12 June 1837 and eventually, by 1840, they had five galvanometers set in a line across the centre of a lozenge-shaped board on which were painted twenty letters. By deflecting any two needles, one letter could be isolated. A Scotsman, William Alexander, on the very day of their initial patent, wrote to Lord John Russell, the then Home Secretary, with a proposal for a telegraph between London and Edinburgh. Three days later an acknowledgement was sent but no action was taken. In December, somewhat unwillingly, Alexander inspected the Wheatstone telegraph and admitted its superiority to his own. THE TELEGRAPH More seriously, there was also Davy, the man who had linked the telegraph to railway safety. Wheatstone was writing to his partner Cooke the January following Alexander's visit Davy has advertised an exhibition of an electric telegraph at Exeter Hall...I am told he employs six wires, by means of which he obtains upwards of two hundred simple and compound signals, and that he rings a bell, I scarcely think that he can effect cither of these things without infringing our patent (Fabie 1884381) Edward Davy, the son of a West Country doctor and inventor of "Davy's Diamond Cement' for mending broken china and glass, had lodged a caveat against rumours of Wheatstone's work the previous March and it seems as if his was the superior scheme. His machine used chemically treated paper strip which recorded the clectrical impulse as a visible brown mark. It was the forerunner of a series of such devices which would eventually lead to the fax machine and television. Only the scientific inadequacies of the Solicitor General, who thought the devices were the same when in fact they were not allowed Wheatstone and Cooke their patent. Dury strenuously struggled to have this decision overturned and to exploit his version with the aid of supporters among the railway men. But in the midst of this battle, which developed in the summer of 1838, he wrote to his father, I have notice of another application for a patent by a person named Morse' (Fahie 1884:431; Emphasis in original) Davy succeeded eventually in obtaining a patent but not in having his British rivals denied, and, upon his emigrating to Australia where he practised his father's profession of medicine, the diffusion of his design ceased although other researchers were to pursue the idea of electro-chemical signal indicators. Cooke and Wheatstone's model was adopted by many British railway companies but, despite secing Day off, in the wider world they were not to triumph. Their bane was to be the person named Morse'. And the reason for his victory over them was less to do with hardware than with what we would today call the software of his system Schilling's contribution, it will be remembered, was not just to use the galvanometer but also to understand that encoding the messages was the clue to efficiency. Binary codes were not new but again date back to antiquity, and in the sixth book of The Advancement and Proficiency of Learning (1604) Bacon gives an example of one, using the letters A and B as the binary base (Thompson 1947:311). At the University of Gttingen, in 1833, Gauss and some colleagues rigged up a telegraph from the physics department offices to the University observatory and the magnetic lab, a distance of 1.25 miles. Using a system along Schilling's lines, the Gttingen faculty evolved a four-bit right/left code. In 1835 25 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE their apparatus became the first to be powered by a magneto-electric machine, a proto-dynamo, rather than a voltaic pile. Morse was to exploit all of these developments, and others. S.E.B. Morse, the American Leonardo', was the son of a New England Congregationalist minister, After Yale, where he had exhibited a talent for art, he had become a professional portraitist and eventually a professor of painting at the forerunner of New York University, the University of the City of New York, A daguerreotypist who took the first photographic portrait in the USA, he was also a child of his time, rabidly anti-immigrant, i.e. anti-Irish and anti-Catholic. His best known paintings were Lafayette and The House of Representatives and his understanding of electricity informal. Crucial to his interest in telegraphy were the fame and proximity of Joseph Henry, subsequently secretary of the Smithsonian but then, in the late 1820s, a professor at the Albany Institute. By substituting numerous small voltaic cells for the large one usually employed in such experiments, Henry had been able to create an electromagnetic pull sufficiently strong to move an arm with a bell attached, Henry, who was called to the chair of Natural Philosophy in the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) in 1832, publicly demonstrated bell-ringing from afar but did not patent the device. Morse, using Henry's apparatus as a starting point, and the expertise of two of his friends who possessed a broader grounding in electrical studies, built a contrivance where in the electrical current deflected a marker across a narrow strip of paper, a recording telegraph. The sender med notched sticks which were pulled across the electrical contact to transmit the imples In September 1837, some two years after he had first made a working model and five years after he began his experiments, he filed a caveat; the Morse system, with its code, was ready Morse's contribution to codes was simple and crucial. He dispatched his assistant Vail and a backer to a printer where the relative frequency of the letters was gauged by examining type fonts. Previous systems, such as Schilling's, seemed to rely on common sense with the vowels represented by the shortest number of impulses but little further refinement. Morse understood, with Schilling and others, that it was casier to train people to learn a code than to find enough different circuits for electricity to display letters. But Morse's crucial insight was that printers experience would reveal the most efficient way to construct such a code. It is for this reason that his system prevailed, SUPPRESSION AND DIFFUSION: OWNING THE TELEGRAPH The diffusion of the telegraph was to be a rather sexed affair since the initial supervening necessity, railroad safety, although sufficiently strong to bring the THETELEGRAPH SCIENTIFIC COMPETENCE TO IDEATION: STATIC ELECTRICAL TELEGRAPHS The application of the natural phenomenon we call electricity to the processes of human communication involves a line of electrical experimenters stretching back to Queen Elizabeth I's physician William Gilbert. The first Englishman to write, in De Magnete, a book based on direct observation, Gilbert coined the phrase vis electrica to describe the property, noticed in antiquity, possessed by amber thatpov, and some other substances which, when rubbed, attracted light materials such as feathers, Further experimentation by the superintendent of the gardens of the King of France in 1733 revealed what Franklin was to call positive and negative charges. In 1745 Musschenbroek built the first device to produce an electric field, the Leyden Jar. His friend, Cunaeus, got a serious electric shock from it. The jar prompted the beginnings of a discussion as to the nature of the phenomenon and a parade of electricians, many of whose names are now immortalised in equipment or units of measure, elaborated, into the early nineteenth century, both the theory of and the laboratory apparatus for creating electrical phenomena. There is another, even older strand of observation also involved in the ground of scientific competence leading to electrical communications systems. Robert Hooke, the experimental physicist, wrote in 1665 I can assure the reader that I have, by the help of a distended wire, propagated the sound a very considerable distance in an instant, or with seemingly as quick a motion as that of light, at least incomparably quicker than that which at the same time was propagated through air; and this was not only in a straight line or direct, but in one bended in many angles (Moncel 1879:11-12) 19 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE FUTURE PERFORMANCE SOCIAL SUPPRESSION OF NECESSITY RADICAL POTENTIAL -government interest obrokers chomware Technology nowe DA WA han be PROTOTYPES INVENTION DIFFUSION 1-Schling 1821 - by 1806 elegraph Gauss at 183 creation of Cocked Western Union SPIN-OFF elegraphs Whatone 1807 Morse 1697 PAST SPIN OFF IDEATION - Schwerter 1656 lephony Ampere before 1820 Science string phones 1885, Trumpet 1671 magretion, clectricity galvanometer 1818. Tagssemaphore 17808 COMPETENCE Figure Telegraphy Hooke was describing a string telephone which enjoys, in the toy box, a popularity that has persisted into the twentieth century (Landes 1983:126). In the decade before the first demonstration of electrical telephones, these string toys were in vogue as an adult diversion, 'Lovers' telegraphs'. They worked up to a distance of 170 yards, the size and nature of the card having some effect on their efficiency, silk being better than hemp Such toys will also figure in the history of the telephone because they all depended upon the attachment of a thread or a wire to a stretched membrane (Moncel 1879:33). Finally, a third, long.observed phenomenon also comes into play as part of the ground of scientific competence leading to telegraphy. Applying magnetic force to move a piece of metal or needle was a trick known in antiquity. St Augustine mentions it in De Civitate Del. Creating false oracles by, for instance, marking letters around a bowl of water in which floated a cork born needle manipulated by a hidden magnet was considered an 'abuse, at least by della Porta (Fahie 1884:5). He can, though, be credited with the first glimmer of the idea of the telegraph to appear in print: "Lastly, owing to the convenience afforded by the 20 THE TELEGRAPH magnet, persons can converse together through long distances...we can communicate what we wish by means of two compass needles circumscribed with an alphabet' (ibid.). In 1635, Schwenteer, in his classements physico-mathematics describes a system using a magnetic needle along these lines, but the experiments which would demonstrate the viability of his idea were not to be conducted until 1819 (Braudel 1981434). The idea of using magnetism and electricity for a signalling system was thus established early in the modern period. The elaboration of the idea as well as the first prototypes for such systems tended to propose the use of static electricity. In one, suggested by an anonymous correspondent of the Scots" Magazine writing from Renfrew in 1753, signalling was to be effected by twenty-six wires with twenty-six electroscopes in the form of mounted pith balls, each to represent one letter Making the electrical circuit agitated the balls. This was the first of many such ideas, another, by Bozolus, a Jesuit, being explained in Latin verse Devices along these lines existed in experimental form by the 1780s. One of the brothers Chappe had begun his telecommunication experiments with thoughts of such a friction telegraph, before perfecting his optical-mechanical system, Optical mechanical systems, such as the Chappe semaphore, can be seen as a sort of precursor to the electrical telegraph, like the string telephones. They are part of the ground of competence rather than prototypes, Received opinion suggests that the supervening necessity for the semaphere was the needs of France's revolutionary armies. Patrice Flichy, however, goes further to point out that the Revolution itself required enhanced communication if the people were to act all over the vastness of France with one mind. The semaphore system was used for civilian communications, for example, decrees of the Convention and causes of the constitution as well as news of political events such as Bonaparte's coup d'tat were all signalled to provincial centres. Strasbourg could communicate with Paris in 36 minutes. Overall, the effect of the semaphore was to help create a new sort of mental landscape which Flichy terms, 'T'espace national". (Flichy 1991:19-23). In France, by the 1840s, there were over 3000 miles of semaphore lines, all operated by the War Department. A law of 1837 established a French government monopoly in long distance communication systems (Brock 1981:136). Lines of semaphore stations were established all over Europe. Nicholas I connected St Petersburg to Warsaw and the German border, with a branch to Moscow, by towers five to six miles apart, 220 towers each with six men. Pre-electric telegraphs, like any other technology, created a certain inertia, and research on electrical alternatives was inhibited. In fact, the existence of these claborate, military systems operated to suppress the efforts of a number of early experimenters working in the static electrical tradition. For example, one of the Wedgwoods, Ralph, planned an electrie telegraph for the benefit of the Admiralty in 1814 but was turned away. Their Lordships' lackeys wrote, "the war being at an end, 21 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE and money scarce, the old system fol shutter semaphores was sufficient for the country" (Fahie 1884:124; brackets in original). The shutter semaphore had been developed in an Admiralty competition by Lord George Murray to improve upon the French device. The inventor of the most elegant of these true electrical prototypes suffered a similar fate In 1816, Francis Ronalds demonstrated an electrical telegraph system that worked over eight miles of wire strung up on frames in his London garden. He mounted clock mechanisms at either end of the wire. In place of the clock hands he had an engraved disk with letters, numbers and other instructions inscribed and in place of the glass was an opaque disk in which an aperture was cut. The clocks being exactly synchronised, the operator waited for the required letter or instruction to appear in the aperture, made the circuit and moved the clectroscope, a pith ball at the other end of the wire. The receiver, seeing what letter was in the second clock's aperture as the ball moved, could note it down. Within two days of receiving notice of this apparatus, Barrow, the secretary of the Admiralty wrote: 'Mr. Barrow presents his compliments to Mr. Ronalds, and acquaints him, with reference to his note of the 3rd inst, that telegraphs of any kind are now wholly unnecessary, and that no other than the one now in use will be adopted' (Fabie 1884:124). Ronalds" is the classic rejected prototype. The last static electrical telegraph was proposed, a true redundancy, in 1873, forty-six years after the dynamie version was invented' Ronalds' experience does not so much reveal official blindness as a lack of supervening social necessity, the reason for such blindness. Ships had flags and armies (and governments) semaphores. They were accepted as partial precursors for the telegraph and they provided as much communication capacity as was required PROTOTYPES, NECESSITY AND 'INVENTION": DYNAMIC ELECTRICAL TELEGRAPHS Systems based on dynamic electricity were proposed in the first decade of the nineteenth century but these too required a discrete circuit for each letter of the alphabet. Instead of pith balls, the idea was to exploit the fact that water decomposes, giving off bubbles when electricity is introduced into it. Using a Voltaic pile and various arrangements of glass flasks, it was possible to indicate letters by these bubbles. The ideation of the modern telegraph had occurred in Schwenteer's suggestion but this was clearly forgotten; for, 175 years later, Ampere had the same sort of thought and proposed that one could by means of as many pairs of conducting wires and magnetic needles as there are letters' establish a signalling system. In 22 THE TELEGRAPH 1819, it was noticed that an electric current would deflect magnetic needles and Faraday discovered that a freely moving magnetised needle when surrounded by a wire coil will respond to the power of the electrical current in the coil. A device, the Galvanometer, to measure currents was built and the would be electrical telegraphers acquired a signalling instrument using dynamic electricity which was to disperse the bubbles and banish the pith balls. The prototype phase of telegraphy ended But there was still question: Who needed a dynamic electrical system for distant signalling? Where was the social necessity to turn these experiments into an 'invention? In 1809, Richard Trevithick brought to London the latest wonder of the country's mining areas, an iron wagon way upon which a steam locomotive ran At Euston Square he built around track within a wooden fence and charged 1 shilling for the ride (Briggs 1979,90). In 1825, the first passenger train to go anywhere ran between Stockton and Darlington. The railway age began somewhat ftfully, Between 1833 and 1843 money was raised to build 2300 miles of railway in the UK, about a quarter of which was constructed during that time (Dyos and Aldcroft 1974:124), Early railways were single-track affairs which necessitated, for the first time, instantaneous signalling methods. One of the many who can lay claim to having "invented the telegraph, Edward Davy, saw this clearly. In 1838 he wrote: The numerous accidents which have occurred on railways seem to call for a remedy of some kind; and when future improvements shall have augmented the speed of railway travelling to a velocity which cannot at present be deemed safe, then every aid which science can afford must be called in to promote this object. Now, there is a contrivance...by which, at every station along the railway line, it may be seen, by mere inspection of a dial, what is the exact situation of the engines running, either towards, or from, that station, and at what speeds they are travelling (Fabie 1884-407) Here then is a real and pressing supervening necessity railway safety. The history of telegraphy offers a clear example of how one technology, in this case the railways, creates a supervening necessity for another, the telegraph. Davy (who is not to be confused with Sir Humphry Davy of the miner's lamp) was eager to have the railway interests exploit the contrivance", a dynamic telegraph of his design. He did not bother the Admiralty and he was right not to. In fact, the earliest telegraph wires did indeed run beside railway tracks and were used for operational purposes. That they could also be used for other messages was 23 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE determined almost immediately. In 1840, the first telegram to excite London, that the Queen had given birth (thereby removing the unpopular King Ernest of Hanover as heir presumptive), was carried from Windsor on the Great Western Railway's telegraph line, developed by Cooke and Wheatstone. Four years later, What hath God wrought", Morse's first public message, was carried down telegraph wire running from Washington to Baltimore along the side of rail tracks In May 1844, the Democratic National Convention was meeting in Baltimore and Silas Wright, its nominee for vice-president, declined the honour by telegram from Washington (Critrom 1982:6). A committee was dispatched by train to check the truth of this communication. The first French wire ran beside the tracks from Paris to St Germain (Thompson 1947:15). The same year which saw the emergence of a clear supervening necessity for the telegraph in the form of the Stockton and Darlington railway also witnessed its 'invention'. Baron Pawel Schilling, a Russian diplomat in Germany, had seen Sommering's apparatus. Using a battery-powered galvanometer, Schilling designed a device that worked in code, Right and left deflections of the needle indicated the letters for example, A=RL, BERRR, CERLL and so on. However, Schilling was working in a repressive society which had anyway made a not inconsiderable investment in the previous optical technology of semaphores. Thus, the Emperor Nicholas saw in it only an instrument of subversion and by an ukase it was, during his reign, absolutely prohibited to give the public any information relative to electric telegraph apparatus, a prohibition which extended even to the translation of the notices respecting it, which, at this time, were appearing in the European Journals. (Thompson 1947:317) Given that the idea of telegraphy had been widely mooted that a system wing common scientific device, the galvanometer, had been demonstrated and that the railways had a need for a signalling system, it is scarcely surprising that claimants for the honour of inventing the telegraph are numerous. Apart from Schilling, Cooke and Wheatstone lowed galvanometers to construct an elegant alphabetic system, which needed initially five, and later two wires to operate. The patent was granted on 12 June 1837 and eventually, by 1840, they had five galvanometers set in a line across the centre of a lozenge-shaped board on which were painted twenty letters. By deflecting any two needles, one letter could be isolated. A Scotsman, William Alexander, on the very day of their initial patent, wrote to Lord John Russell, the then Home Secretary, with a proposal for a telegraph between London and Edinburgh. Three days later an acknowledgement was sent but no action was taken. In December, somewhat unwillingly, Alexander inspected the Wheatstone telegraph and admitted its superiority to his own. THE TELEGRAPH More seriously, there was also Davy, the man who had linked the telegraph to railway safety. Wheatstone was writing to his partner Cooke the January following Alexander's visit Davy has advertised an exhibition of an electric telegraph at Exeter Hall...I am told he employs six wires, by means of which he obtains upwards of two hundred simple and compound signals, and that he rings a bell, I scarcely think that he can effect cither of these things without infringing our patent (Fabie 1884381) Edward Davy, the son of a West Country doctor and inventor of "Davy's Diamond Cement' for mending broken china and glass, had lodged a caveat against rumours of Wheatstone's work the previous March and it seems as if his was the superior scheme. His machine used chemically treated paper strip which recorded the clectrical impulse as a visible brown mark. It was the forerunner of a series of such devices which would eventually lead to the fax machine and television. Only the scientific inadequacies of the Solicitor General, who thought the devices were the same when in fact they were not allowed Wheatstone and Cooke their patent. Dury strenuously struggled to have this decision overturned and to exploit his version with the aid of supporters among the railway men. But in the midst of this battle, which developed in the summer of 1838, he wrote to his father, I have notice of another application for a patent by a person named Morse' (Fahie 1884:431; Emphasis in original) Davy succeeded eventually in obtaining a patent but not in having his British rivals denied, and, upon his emigrating to Australia where he practised his father's profession of medicine, the diffusion of his design ceased although other researchers were to pursue the idea of electro-chemical signal indicators. Cooke and Wheatstone's model was adopted by many British railway companies but, despite secing Day off, in the wider world they were not to triumph. Their bane was to be the person named Morse'. And the reason for his victory over them was less to do with hardware than with what we would today call the software of his system Schilling's contribution, it will be remembered, was not just to use the galvanometer but also to understand that encoding the messages was the clue to efficiency. Binary codes were not new but again date back to antiquity, and in the sixth book of The Advancement and Proficiency of Learning (1604) Bacon gives an example of one, using the letters A and B as the binary base (Thompson 1947:311). At the University of Gttingen, in 1833, Gauss and some colleagues rigged up a telegraph from the physics department offices to the University observatory and the magnetic lab, a distance of 1.25 miles. Using a system along Schilling's lines, the Gttingen faculty evolved a four-bit right/left code. In 1835 25 PROPAGATING SOUND AT DISTANCE their apparatus became the first to be powered by a magneto-electric machine, a proto-dynamo, rather than a voltaic pile. Morse was to exploit all of these developments, and others. S.E.B. Morse, the American Leonardo', was the son of a New England Congregationalist minister, After Yale, where he had exhibited a talent for art, he had become a professional portraitist and eventually a professor of painting at the forerunner of New York University, the University of the City of New York, A daguerreotypist who took the first photographic portrait in the USA, he was also a child of his time, rabidly anti-immigrant, i.e. anti-Irish and anti-Catholic. His best known paintings were Lafayette and The House of Representatives and his understanding of electricity informal. Crucial to his interest in telegraphy were the fame and proximity of Joseph Henry, subsequently secretary of the Smithsonian but then, in the late 1820s, a professor at the Albany Institute. By substituting numerous small voltaic cells for the large one usually employed in such experiments, Henry had been able to create an electromagnetic pull sufficiently strong to move an arm with a bell attached, Henry, who was called to the chair of Natural Philosophy in the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) in 1832, publicly demonstrated bell-ringing from afar but did not patent the device. Morse, using Henry's apparatus as a starting point, and the expertise of two of his friends who possessed a broader grounding in electrical studies, built a contrivance where in the electrical current deflected a marker across a narrow strip of paper, a recording telegraph. The sender med notched sticks which were pulled across the electrical contact to transmit the imples In September 1837, some two years after he had first made a working model and five years after he began his experiments, he filed a caveat; the Morse system, with its code, was ready Morse's contribution to codes was simple and crucial. He dispatched his assistant Vail and a backer to a printer where the relative frequency of the letters was gauged by examining type fonts. Previous systems, such as Schilling's, seemed to rely on common sense with the vowels represented by the shortest number of impulses but little further refinement. Morse understood, with Schilling and others, that it was casier to train people to learn a code than to find enough different circuits for electricity to display letters. But Morse's crucial insight was that printers experience would reveal the most efficient way to construct such a code. It is for this reason that his system prevailed, SUPPRESSION AND DIFFUSION: OWNING THE TELEGRAPH The diffusion of the telegraph was to be a rather sexed affair since the initial supervening necessity, railroad safety, although sufficiently strong to bring the

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

1 Expert Approved Answer

Step: 1 Unlock

Question Has Been Solved by an Expert!

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts

Step: 2 Unlock

Step: 3 Unlock