Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

1. Using an accrual system, prepare an operating statement for the year and a balance sheet as of December 31 . What do these statements

1. Using an accrual system, prepare an operating statement for the year and a balance sheet as of December 31. What do these statements tell you about BOGAs profitability?

2. In the absence of the banks stipulation that accrual be used, which type of systemmodified cash or accrualwould you recommend that Dr. Amsted use for BOGA? Why?

Please answer the questions completely and all spam answers will be reported.

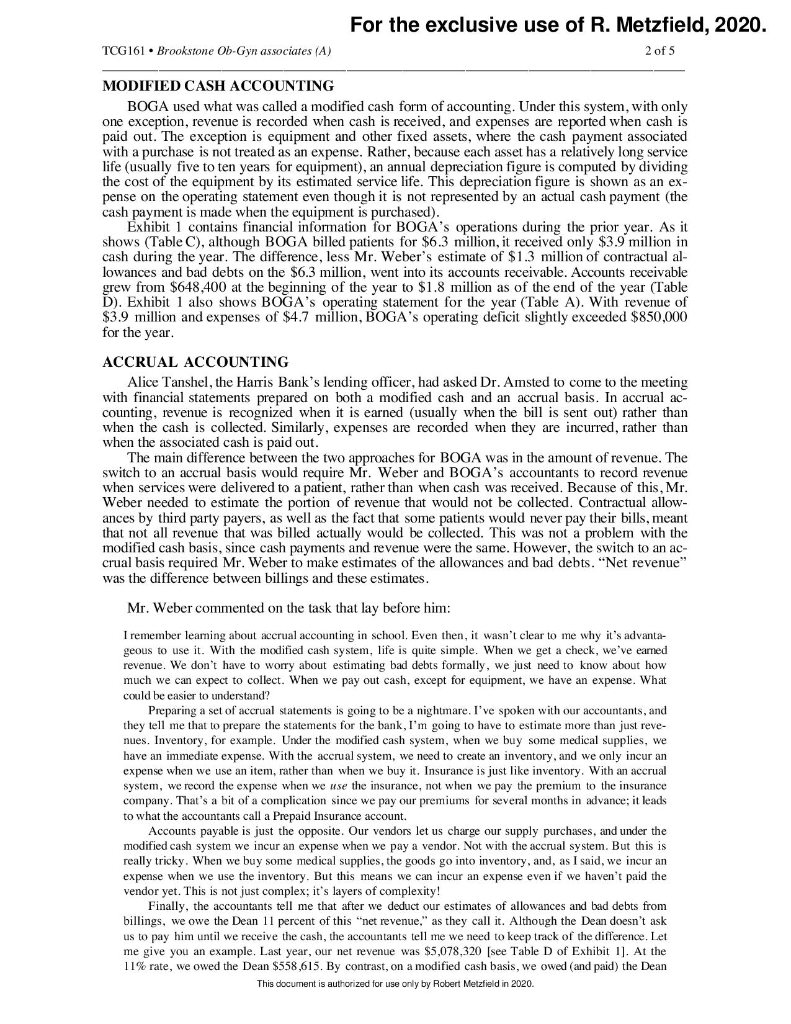

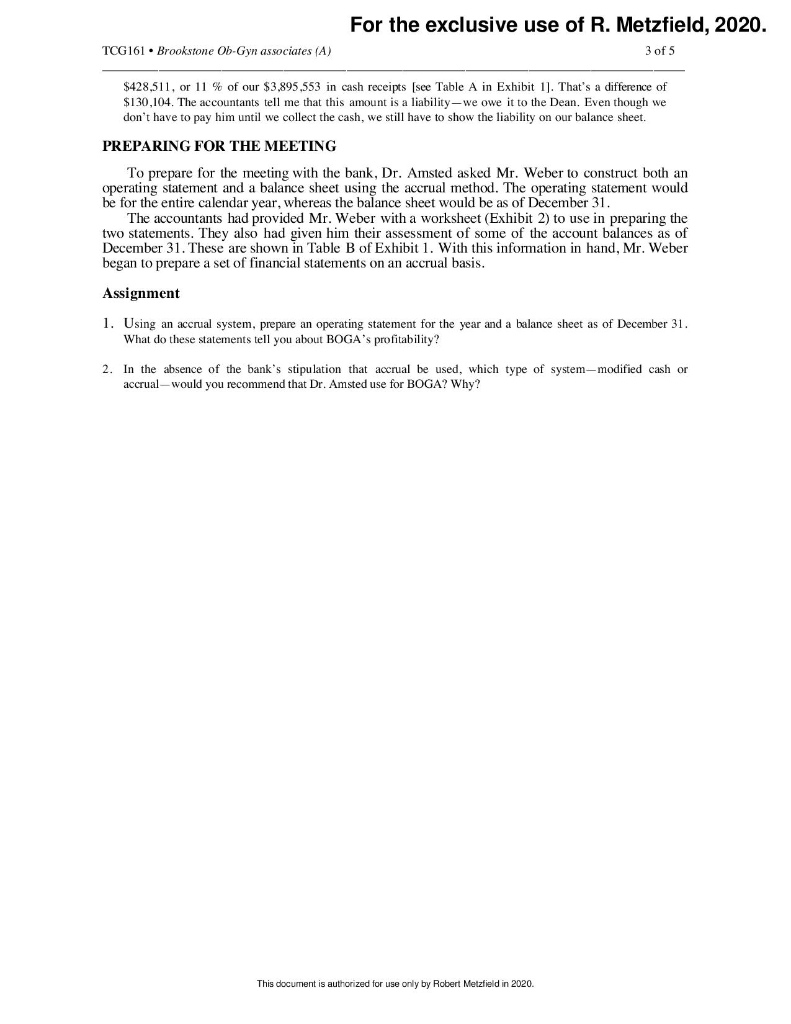

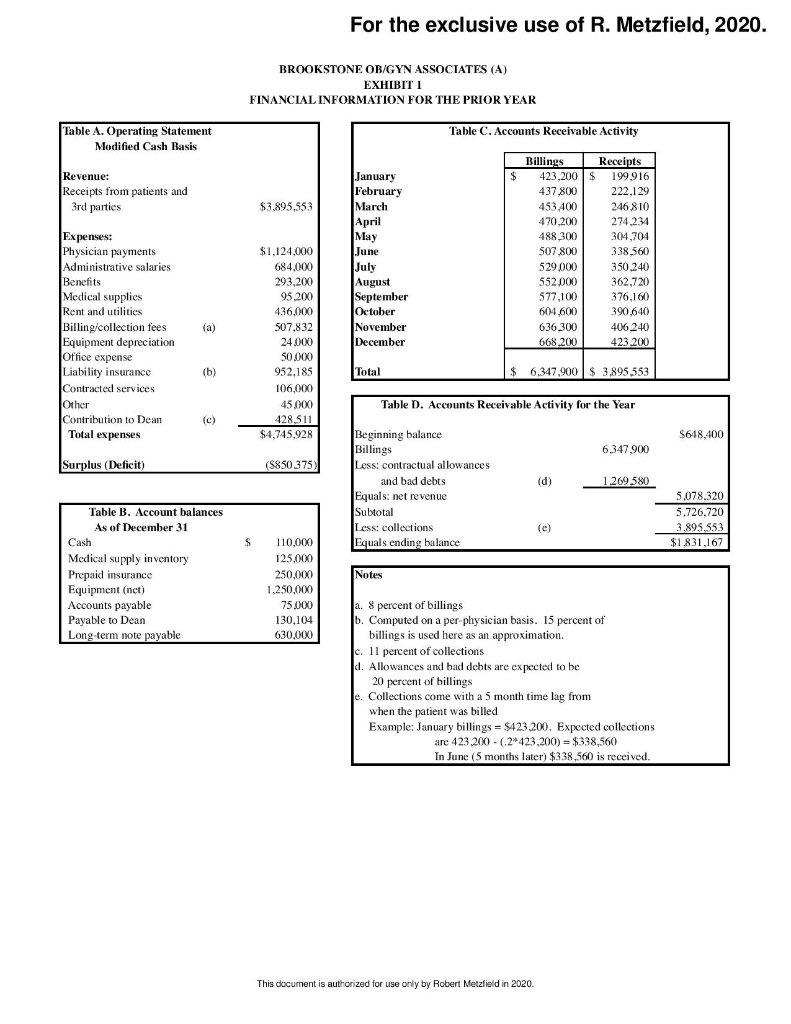

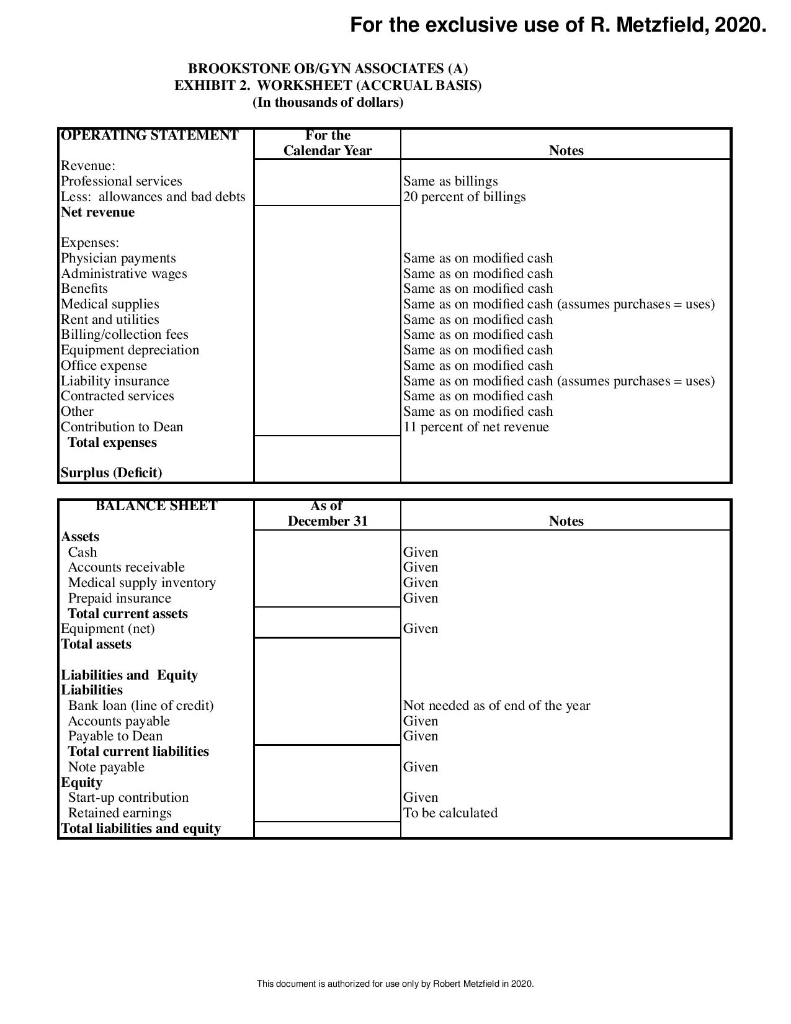

For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. HBSP Product Number TCG 161 THE CRIMSON PRESS CURRICULUM CENTER THE CRIMSON GROUP, INC. Brookstone Ob-Gyn Associates (A) In January, Mark Amsted, M.D., Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brookstone Medical School, Chief of Ob-Gyn at Brookstone Medical Center, and President of Brookstone Ob-Gyn Associates (BOGA), was preparing to meet with the Harris National Bank. He planned to present a request for a $300,000 line of credit, the approval of which was critical to BOGA's continued op- erations. He had discussed the need for the line of credit with the Dean of the Medical School, and had obtained approval to make the request to the bank, but he was by no means certain that the bank would agree to the loan. A great deal depended upon the bank's reaction to the financial informa- tion that he and his business manager, Randy Weber, planned to present. BACKGROUND BOGA was a faculty practice plan comprised of university faculty physicians in obstetrics and gynecology (OB-Gyn). All BOGA physicians were on the staff of Brookstone Medical Center (BMC), one of the city's major teaching hospitals. The hospital was affiliated with the Brookstone Medical School, and all of BOGA's physicians held faculty appointments in the medical school. BOGA had been organized several years earlier as a nonprofit educational trust. Initially, its offices had been located in the hospital, and it had grown slowly. During its first few years of exis- tence, BOGA's physicians saw mainly Medicaid, Medicare, and self-pay (or uninsured) patients in the hospital's outpatient department. Several years ago, Brookstone Medical Center began to experience declining Ob-Gyn admis- sions due to competition from some nearby community hospitals. As a result, BMC offered to con- tribute $1 million to BOGA if it would open offices in a nearby building. The idea was to make BOGA's facilities more attractive to patients with private insurance, in the hope that these patients would use its services. If the idea worked, BMC would reverse the declining trend in its Ob-Gyn admissions, and would do so with fully insured patients. After discussing BMC's proposal with his colleagues, Dr. Amsted accepted the offer. Dr. Amsted supplemented the $1 million contribution from the medical center with a long-term note from the Harris National Bank. The funds were used to purchase new medical and office equipment, renovate the space, and furnish the offices in the new facility. The surrounding community responded positively to BOGA's move. The reputation of BOGA's physicians and the attractiveness of the new facilities led to increases in the number of private insurance patients treated. In each of the last two years, BOGA's revenue has increased by about 20 percent over the previous year. PROBLEMS Despite the growth in revenues, BOGA's profitability was becoming an issue. Indeed, as he began to prepare for his meeting with the bank, Dr. Amsted was quite perplexed. He commented: It's crazy. Despite our rapid rate of growth, we're losing money, and I don't understand why. Our salaries are competitive and our physicians see as many patients per hour as Ob-Gyn physicians in other places. Our scheduling is good, so we don't have a lot of downtime. All our other costs seem quite reasonable. Yet, the figures speak for themselves. Last year, we lost $850,000! According to Randy, if we don't get the line of credit from the bank, we won't be able to meet some of our payroll and other expenses next month. Even if the bank gives us the loan, I'm sure they'll ask me to either cut expenses or increase our charges so we'll be profitable. The problem is that the charges are re stricted by our third parties, and I can see no place to cut expenses other than by laying people off. I'm re- luctant to do that, though, since everyone seems overworked. This case was prepared by Professor David W. Young. It is intended as a basis for class discussion and not to illus- trate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright 2014 by The Crimson Group, Inc. To order copies or request permission to reproduce this document, contact Harvard Business Publications (http://hbsp.harvard.edu/). Under provisions of United States and interna- tional copyright laws, no part of this document may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from The Crimson Group (www.thecrimsongroup.org) This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. TCG161 Brookstone Ob-Gyn associates (A) 2 of 5 MODIFIED CASH ACCOUNTING BOGA used what was called a modified cash form of accounting. Under this system, with only one exception, revenue is recorded when cash is received, and expenses are reported when cash is paid out. The exception is equipment and other fixed assets, where the cash payment associated with a purchase is not treated as an expense. Rather, because each asset has a relatively long service life (usually five to ten years for equipment), an annual depreciation figure is computed by dividing the cost of the equipment by its estimated service life. This depreciation figure is shown as an ex- pense on the operating statement even though it is not represented by an actual cash payment (the cash payment is made when the equipment is purchased). Exhibit 1 contains financial information for BOGA's operations during the prior year. As it shows (Table C), although BOGA billed patients for $6.3 million, it received only $3.9 million in cash during the year. The difference, less Mr. Weber's estimate of $1.3 million of contractual al- lowances and bad debts on the $6.3 million, we into its accounts receivable. Accounts receivable grew from $648,400 at the beginning of the year to $1.8 million as of the end of the year (Table D). Exhibit 1 also shows BOGA's operating statement for the year (Table A). With revenue of $3.9 million and expenses of $4.7 million, BOGA's operating deficit slightly exceeded $850,000 for the year. ACCRUAL ACCOUNTING Alice Tanshel, the Harris Bank's lending officer, had asked Dr. Amsted to come to the meeting with financial statements prepared on both a modified cash and an accrual basis. In accrual ac- counting, revenue is recognized when it is earned (usually when the bill is sent out) rather than when the cash is collected. Similarly, expenses are recorded when they are incurred, rather than when the associated cash is paid out. The main difference between the two approaches for BOGA was in the amount of revenue. The switch to an accrual basis would require Mr. Weber and BOGA's accountants to record revenue when services were delivered to a patient, rather than when cash was received. Because of this, Mr. Weber needed to estimate the portion of revenue that would not be collected. Contractual allow- ances by third party payers, as well as the fact that some patients would never pay their bills, meant that not all revenue that was billed actually would collected. This was not a problem with the modified cash basis, since cash payments and revenue were the same. However, the switch to an ac- crual basis required Mr. Weber to make estimates of the allowances and bad debts. "Net revenue" was the difference between billings and these estimates. Mr. Weber commented on the task that lay before him: I remember leaming about accrual accounting in school. Even then, it wasn't clear to me why it's advanta- geous to use it. With the modified cash system, life is quite simple. When we get a check, we've eamed revenue. We don't have to worry about estimating bad debts formally, we just need to know about how much we can expect to collect. When we pay out cash, except for equipment, we have an expense. What could be easier to understand? Preparing a set of accrual statements is going to be a nightmare. I've spoken with our accountants, and they tell me that to prepare the statements for the bank, I'm going to have to estimate more than just reve- nues. Inventory, for example. Under the modified cash system, when we buy some medical supplies, we have an immediate expense. With the accrual system, we need to create an inventory, and we only incur an expense when we use an item, rather than when we buy it. Insurance is just like inventory. With an accrual system, we record the expense when we use the insurance, not when we pay the premium to the insurance company. That's a bit of a complication since we pay our premiums for several months in advance; it leads to what the accountants call a Prepaid Insurance account. Accounts payable is just the opposite. Our vendors let us charge our supply purchases, and under the modified cash system we incur an expense when we pay a vendor. Not with the accrual system. But this is really tricky. When we buy some medical supplies, the goods go into inventory, and, as I said, we incur an expense when we use the inventory. But this means we can incur an expense even if we haven't paid the vendor yet. This is not just complex, it's layers of complexity! Finally, the accountants tell me that after we deduct our estimates of allowances and bad debts from billings, we owe the Dean 11 percent of this "net revenue," as they call it. Although the Dean doesn't ask us to pay him until we receive the cash, the accountants tell me we need to keep track of the difference. Let me give you an example. Last year, our net revenue was $5,078,320 (see Table D of Exhibit 1). At the 11% rate, we owed the Dean $558,615. By contrast, on a modified cash basis, we owed (and paid) the Dean This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. TCG161 Brookstone Ob-Gyn associates (A) 3 of 5 $428,511, or 11 % of our $3,895,553 in cash receipts (see Table A in Exhibit 1). That's a difference of $130,104. The accountants tell me that this amount is a liability-we owe it to the Dean. Even though we don't have to pay him until we collect the cash, we still have to show the liability on our balance sheet. PREPARING FOR THE MEETING To prepare for the meeting with the bank, Dr. Amsted asked Mr. Weber to construct both an operating statement and a balance sheet using the accrual method. The operating statement would be for the entire calendar year, whereas the balance sheet would be as of December 31. The accountants had provided Mr.Weber with a worksheet (Exhibit 2) to use in preparing the two statements. They also had given him their assessment of some of the account balances as of December 31. These are shown in Table B of Exhibit 1. With this information in hand, Mr. Weber began to prepare a set of financial statements on an accrual basis. Assignment balance sheet as of December 31. 1. Using an accrual system, prepare an operating statement for the year and What do these statements tell you about BOGA's profitability? 2. In the absence of the bank's stipulation that accrual be used, which type of system-modified cash or accrual - would you recommend that Dr. Amsted use for BOGA? Why? This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. BROOKSTONE OB/GYN ASSOCIATES (A) /A EXHIBIT 1 FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE PRIOR YEAR Table A. Operating Statement Modified Cash Basis Table C. Accounts Receivable Activity Revenue: Receipts from patients and 3rd parties $3,895,553 Expenses: Physician payments Administrative salaries Benefits Medical supplies Rent and utilities Billing/collection fees Equipment depreciation Office expense Liability insurance Contracted services Other Contribution to Dean Total expenses January February March April |May June July August September October November December $1,124,000 684.000 293,200 95,200 436,000 507,832 24.000 50.000 952,185 106,000 45.000 428,511 $4,745,928 (a) Billings Receipts $ 423,200 $ 199,916 437,800 222.129 453.400 246,810 470.200 274.234 488,300 304,704 507 800 338,560 529.000 350,240 552.000 362.720 577.100 376,160 604.600 390.640 636,300 406.240 668,200 423.200 (b) b Total $ 6,347,900 $ 3,895,553 Table D. Accounts Receivable Activity for the Year (c) $648,400 6,347,900 Surplus (Deficit) (5850.375) (d) 1.269.580 Beginning balance Billings Less: contractual allowances and bad debts Equals: net revenue Subtotal Less: collections Equals ending balance 5,078.320 5.726.720 3.895,553 $1831,167 (e) S Table B. Account balances As of December 31 Cash Medical supply inventory Prepaid insurance Equipment (net) Accounts payable Payable to Dean Long-term note payable Notes 110,000 125.000 250.000 1,250,000 75.000 130,104 630,000 a. 8 percent of billings Computed on a per-physician basis. 15 percent of billings is used here as an approximation 11 percent of collections d. Allowances and bad debts are expected to be 20 percent of billings Collections come with a 5 month time lag from when the patient was billed Example: January billings = $423.200. Expected collections are 423,200 - (2*423,200) = $338,560 In June (5 months later) $338,560 is received This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. BROOKSTONE OB/GYN ASSOCIATES (A) EXHIBIT 2. WORKSHEET (ACCRUAL BASIS) (In thousands of dollars) OPERATING STATEMENT For the Calendar Year Notes Revenue: Professional services Less: allowances and bad debts Net revenue Same as billings 20 percent of billings Expenses: Physician payments Administrative wages Benefits Medical supplies Rent and utilities Billing/collection fees Equipment depreciation Liability insurance Contracted services Other Contribution to Dean Total expenses Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash (assumes purchases = uses) Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash (assumes purchases = uses) Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash 11 percent of net revenue Office expense Surplus (Deficit) BALANCE SHEET AS OT December 31 Notes Assets Cash Accounts receivable Medical supply inventory Prepaid insurance Total current assets Equipment (net) Total assets Given Given Given Given Given Not needed as of end of the year Given Given Liabilities and Equity Liabilities Bank loan (line of credit) Accounts payable Payable to Dean Total current liabilities Note payable Equity Start-up contribution Retained earnings Total liabilities and equity Given Given To be calculated This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. HBSP Product Number TCG 161 THE CRIMSON PRESS CURRICULUM CENTER THE CRIMSON GROUP, INC. Brookstone Ob-Gyn Associates (A) In January, Mark Amsted, M.D., Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Brookstone Medical School, Chief of Ob-Gyn at Brookstone Medical Center, and President of Brookstone Ob-Gyn Associates (BOGA), was preparing to meet with the Harris National Bank. He planned to present a request for a $300,000 line of credit, the approval of which was critical to BOGA's continued op- erations. He had discussed the need for the line of credit with the Dean of the Medical School, and had obtained approval to make the request to the bank, but he was by no means certain that the bank would agree to the loan. A great deal depended upon the bank's reaction to the financial informa- tion that he and his business manager, Randy Weber, planned to present. BACKGROUND BOGA was a faculty practice plan comprised of university faculty physicians in obstetrics and gynecology (OB-Gyn). All BOGA physicians were on the staff of Brookstone Medical Center (BMC), one of the city's major teaching hospitals. The hospital was affiliated with the Brookstone Medical School, and all of BOGA's physicians held faculty appointments in the medical school. BOGA had been organized several years earlier as a nonprofit educational trust. Initially, its offices had been located in the hospital, and it had grown slowly. During its first few years of exis- tence, BOGA's physicians saw mainly Medicaid, Medicare, and self-pay (or uninsured) patients in the hospital's outpatient department. Several years ago, Brookstone Medical Center began to experience declining Ob-Gyn admis- sions due to competition from some nearby community hospitals. As a result, BMC offered to con- tribute $1 million to BOGA if it would open offices in a nearby building. The idea was to make BOGA's facilities more attractive to patients with private insurance, in the hope that these patients would use its services. If the idea worked, BMC would reverse the declining trend in its Ob-Gyn admissions, and would do so with fully insured patients. After discussing BMC's proposal with his colleagues, Dr. Amsted accepted the offer. Dr. Amsted supplemented the $1 million contribution from the medical center with a long-term note from the Harris National Bank. The funds were used to purchase new medical and office equipment, renovate the space, and furnish the offices in the new facility. The surrounding community responded positively to BOGA's move. The reputation of BOGA's physicians and the attractiveness of the new facilities led to increases in the number of private insurance patients treated. In each of the last two years, BOGA's revenue has increased by about 20 percent over the previous year. PROBLEMS Despite the growth in revenues, BOGA's profitability was becoming an issue. Indeed, as he began to prepare for his meeting with the bank, Dr. Amsted was quite perplexed. He commented: It's crazy. Despite our rapid rate of growth, we're losing money, and I don't understand why. Our salaries are competitive and our physicians see as many patients per hour as Ob-Gyn physicians in other places. Our scheduling is good, so we don't have a lot of downtime. All our other costs seem quite reasonable. Yet, the figures speak for themselves. Last year, we lost $850,000! According to Randy, if we don't get the line of credit from the bank, we won't be able to meet some of our payroll and other expenses next month. Even if the bank gives us the loan, I'm sure they'll ask me to either cut expenses or increase our charges so we'll be profitable. The problem is that the charges are re stricted by our third parties, and I can see no place to cut expenses other than by laying people off. I'm re- luctant to do that, though, since everyone seems overworked. This case was prepared by Professor David W. Young. It is intended as a basis for class discussion and not to illus- trate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Copyright 2014 by The Crimson Group, Inc. To order copies or request permission to reproduce this document, contact Harvard Business Publications (http://hbsp.harvard.edu/). Under provisions of United States and interna- tional copyright laws, no part of this document may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from The Crimson Group (www.thecrimsongroup.org) This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. TCG161 Brookstone Ob-Gyn associates (A) 2 of 5 MODIFIED CASH ACCOUNTING BOGA used what was called a modified cash form of accounting. Under this system, with only one exception, revenue is recorded when cash is received, and expenses are reported when cash is paid out. The exception is equipment and other fixed assets, where the cash payment associated with a purchase is not treated as an expense. Rather, because each asset has a relatively long service life (usually five to ten years for equipment), an annual depreciation figure is computed by dividing the cost of the equipment by its estimated service life. This depreciation figure is shown as an ex- pense on the operating statement even though it is not represented by an actual cash payment (the cash payment is made when the equipment is purchased). Exhibit 1 contains financial information for BOGA's operations during the prior year. As it shows (Table C), although BOGA billed patients for $6.3 million, it received only $3.9 million in cash during the year. The difference, less Mr. Weber's estimate of $1.3 million of contractual al- lowances and bad debts on the $6.3 million, we into its accounts receivable. Accounts receivable grew from $648,400 at the beginning of the year to $1.8 million as of the end of the year (Table D). Exhibit 1 also shows BOGA's operating statement for the year (Table A). With revenue of $3.9 million and expenses of $4.7 million, BOGA's operating deficit slightly exceeded $850,000 for the year. ACCRUAL ACCOUNTING Alice Tanshel, the Harris Bank's lending officer, had asked Dr. Amsted to come to the meeting with financial statements prepared on both a modified cash and an accrual basis. In accrual ac- counting, revenue is recognized when it is earned (usually when the bill is sent out) rather than when the cash is collected. Similarly, expenses are recorded when they are incurred, rather than when the associated cash is paid out. The main difference between the two approaches for BOGA was in the amount of revenue. The switch to an accrual basis would require Mr. Weber and BOGA's accountants to record revenue when services were delivered to a patient, rather than when cash was received. Because of this, Mr. Weber needed to estimate the portion of revenue that would not be collected. Contractual allow- ances by third party payers, as well as the fact that some patients would never pay their bills, meant that not all revenue that was billed actually would collected. This was not a problem with the modified cash basis, since cash payments and revenue were the same. However, the switch to an ac- crual basis required Mr. Weber to make estimates of the allowances and bad debts. "Net revenue" was the difference between billings and these estimates. Mr. Weber commented on the task that lay before him: I remember leaming about accrual accounting in school. Even then, it wasn't clear to me why it's advanta- geous to use it. With the modified cash system, life is quite simple. When we get a check, we've eamed revenue. We don't have to worry about estimating bad debts formally, we just need to know about how much we can expect to collect. When we pay out cash, except for equipment, we have an expense. What could be easier to understand? Preparing a set of accrual statements is going to be a nightmare. I've spoken with our accountants, and they tell me that to prepare the statements for the bank, I'm going to have to estimate more than just reve- nues. Inventory, for example. Under the modified cash system, when we buy some medical supplies, we have an immediate expense. With the accrual system, we need to create an inventory, and we only incur an expense when we use an item, rather than when we buy it. Insurance is just like inventory. With an accrual system, we record the expense when we use the insurance, not when we pay the premium to the insurance company. That's a bit of a complication since we pay our premiums for several months in advance; it leads to what the accountants call a Prepaid Insurance account. Accounts payable is just the opposite. Our vendors let us charge our supply purchases, and under the modified cash system we incur an expense when we pay a vendor. Not with the accrual system. But this is really tricky. When we buy some medical supplies, the goods go into inventory, and, as I said, we incur an expense when we use the inventory. But this means we can incur an expense even if we haven't paid the vendor yet. This is not just complex, it's layers of complexity! Finally, the accountants tell me that after we deduct our estimates of allowances and bad debts from billings, we owe the Dean 11 percent of this "net revenue," as they call it. Although the Dean doesn't ask us to pay him until we receive the cash, the accountants tell me we need to keep track of the difference. Let me give you an example. Last year, our net revenue was $5,078,320 (see Table D of Exhibit 1). At the 11% rate, we owed the Dean $558,615. By contrast, on a modified cash basis, we owed (and paid) the Dean This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. TCG161 Brookstone Ob-Gyn associates (A) 3 of 5 $428,511, or 11 % of our $3,895,553 in cash receipts (see Table A in Exhibit 1). That's a difference of $130,104. The accountants tell me that this amount is a liability-we owe it to the Dean. Even though we don't have to pay him until we collect the cash, we still have to show the liability on our balance sheet. PREPARING FOR THE MEETING To prepare for the meeting with the bank, Dr. Amsted asked Mr. Weber to construct both an operating statement and a balance sheet using the accrual method. The operating statement would be for the entire calendar year, whereas the balance sheet would be as of December 31. The accountants had provided Mr.Weber with a worksheet (Exhibit 2) to use in preparing the two statements. They also had given him their assessment of some of the account balances as of December 31. These are shown in Table B of Exhibit 1. With this information in hand, Mr. Weber began to prepare a set of financial statements on an accrual basis. Assignment balance sheet as of December 31. 1. Using an accrual system, prepare an operating statement for the year and What do these statements tell you about BOGA's profitability? 2. In the absence of the bank's stipulation that accrual be used, which type of system-modified cash or accrual - would you recommend that Dr. Amsted use for BOGA? Why? This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. BROOKSTONE OB/GYN ASSOCIATES (A) /A EXHIBIT 1 FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR THE PRIOR YEAR Table A. Operating Statement Modified Cash Basis Table C. Accounts Receivable Activity Revenue: Receipts from patients and 3rd parties $3,895,553 Expenses: Physician payments Administrative salaries Benefits Medical supplies Rent and utilities Billing/collection fees Equipment depreciation Office expense Liability insurance Contracted services Other Contribution to Dean Total expenses January February March April |May June July August September October November December $1,124,000 684.000 293,200 95,200 436,000 507,832 24.000 50.000 952,185 106,000 45.000 428,511 $4,745,928 (a) Billings Receipts $ 423,200 $ 199,916 437,800 222.129 453.400 246,810 470.200 274.234 488,300 304,704 507 800 338,560 529.000 350,240 552.000 362.720 577.100 376,160 604.600 390.640 636,300 406.240 668,200 423.200 (b) b Total $ 6,347,900 $ 3,895,553 Table D. Accounts Receivable Activity for the Year (c) $648,400 6,347,900 Surplus (Deficit) (5850.375) (d) 1.269.580 Beginning balance Billings Less: contractual allowances and bad debts Equals: net revenue Subtotal Less: collections Equals ending balance 5,078.320 5.726.720 3.895,553 $1831,167 (e) S Table B. Account balances As of December 31 Cash Medical supply inventory Prepaid insurance Equipment (net) Accounts payable Payable to Dean Long-term note payable Notes 110,000 125.000 250.000 1,250,000 75.000 130,104 630,000 a. 8 percent of billings Computed on a per-physician basis. 15 percent of billings is used here as an approximation 11 percent of collections d. Allowances and bad debts are expected to be 20 percent of billings Collections come with a 5 month time lag from when the patient was billed Example: January billings = $423.200. Expected collections are 423,200 - (2*423,200) = $338,560 In June (5 months later) $338,560 is received This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020. For the exclusive use of R. Metzfield, 2020. BROOKSTONE OB/GYN ASSOCIATES (A) EXHIBIT 2. WORKSHEET (ACCRUAL BASIS) (In thousands of dollars) OPERATING STATEMENT For the Calendar Year Notes Revenue: Professional services Less: allowances and bad debts Net revenue Same as billings 20 percent of billings Expenses: Physician payments Administrative wages Benefits Medical supplies Rent and utilities Billing/collection fees Equipment depreciation Liability insurance Contracted services Other Contribution to Dean Total expenses Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash (assumes purchases = uses) Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash (assumes purchases = uses) Same as on modified cash Same as on modified cash 11 percent of net revenue Office expense Surplus (Deficit) BALANCE SHEET AS OT December 31 Notes Assets Cash Accounts receivable Medical supply inventory Prepaid insurance Total current assets Equipment (net) Total assets Given Given Given Given Given Not needed as of end of the year Given Given Liabilities and Equity Liabilities Bank loan (line of credit) Accounts payable Payable to Dean Total current liabilities Note payable Equity Start-up contribution Retained earnings Total liabilities and equity Given Given To be calculated This document is authorized for use only by Robert Metzfield in 2020

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started