Answered step by step

Verified Expert Solution

Question

1 Approved Answer

1-l need long introduction about (RW CITRUS & JUICE: INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER) case study. 2_I need long answer for this question in the same case

1-l need long introduction about (RW CITRUS & JUICE: INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER) case study.

2_I need long answer for this question in the same case (3. What is the bare minimum that needs to be in place operationally so that the juice orders can be filled consistently and efficiently?)

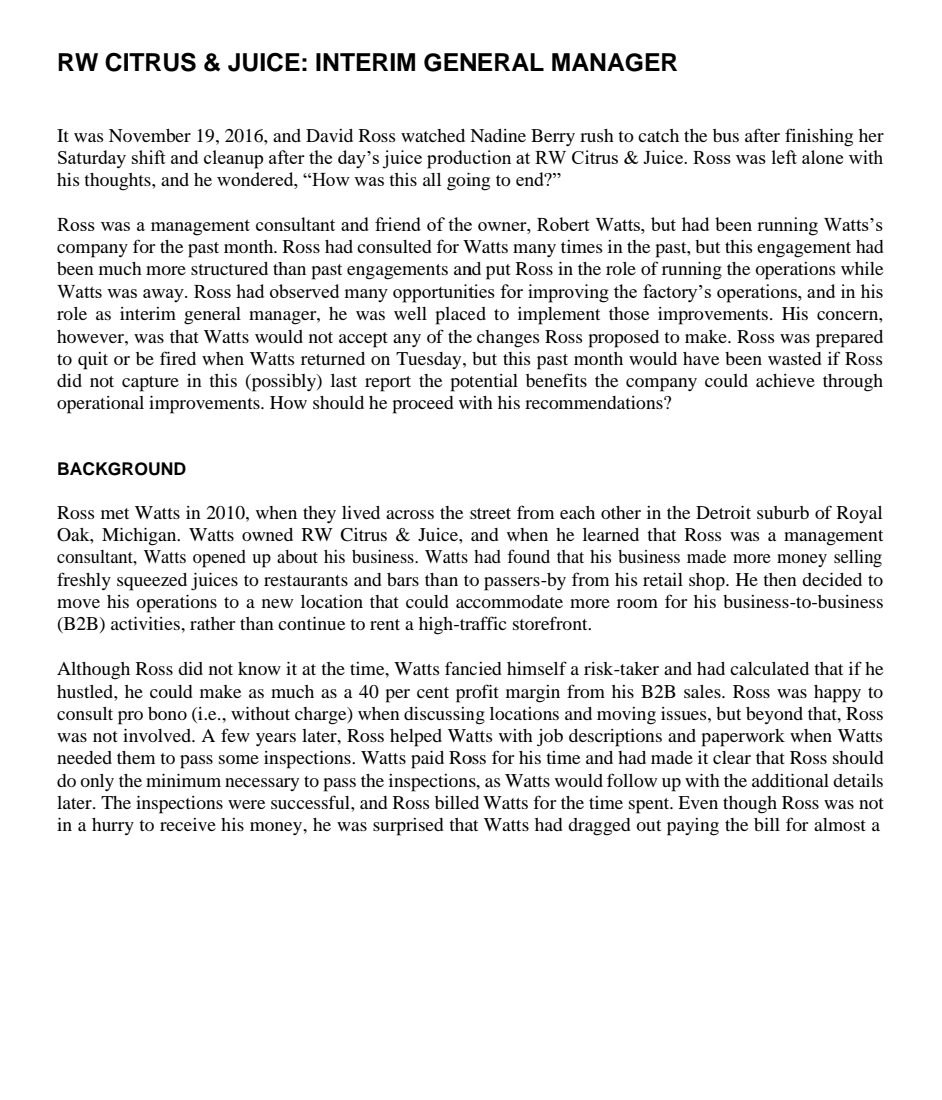

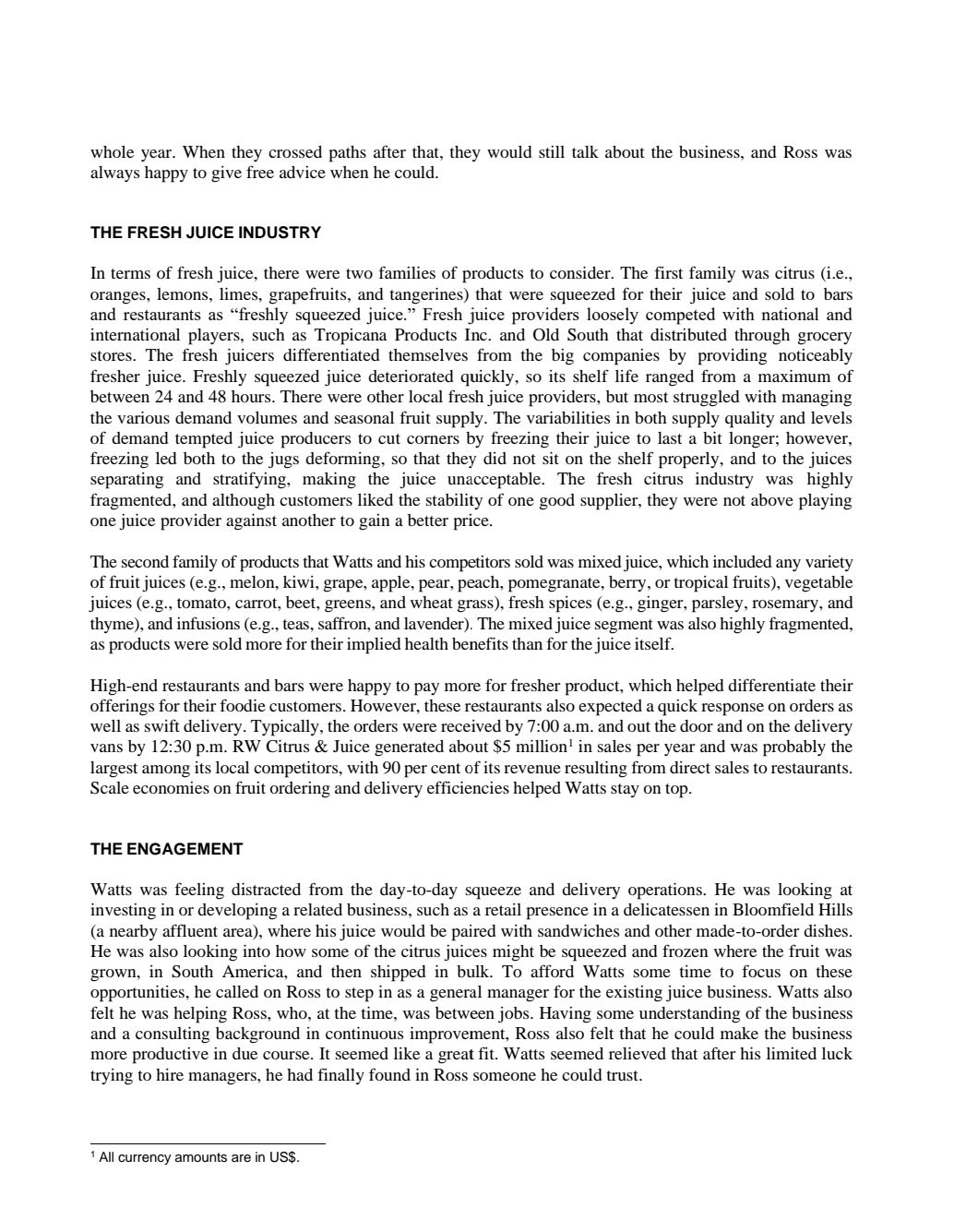

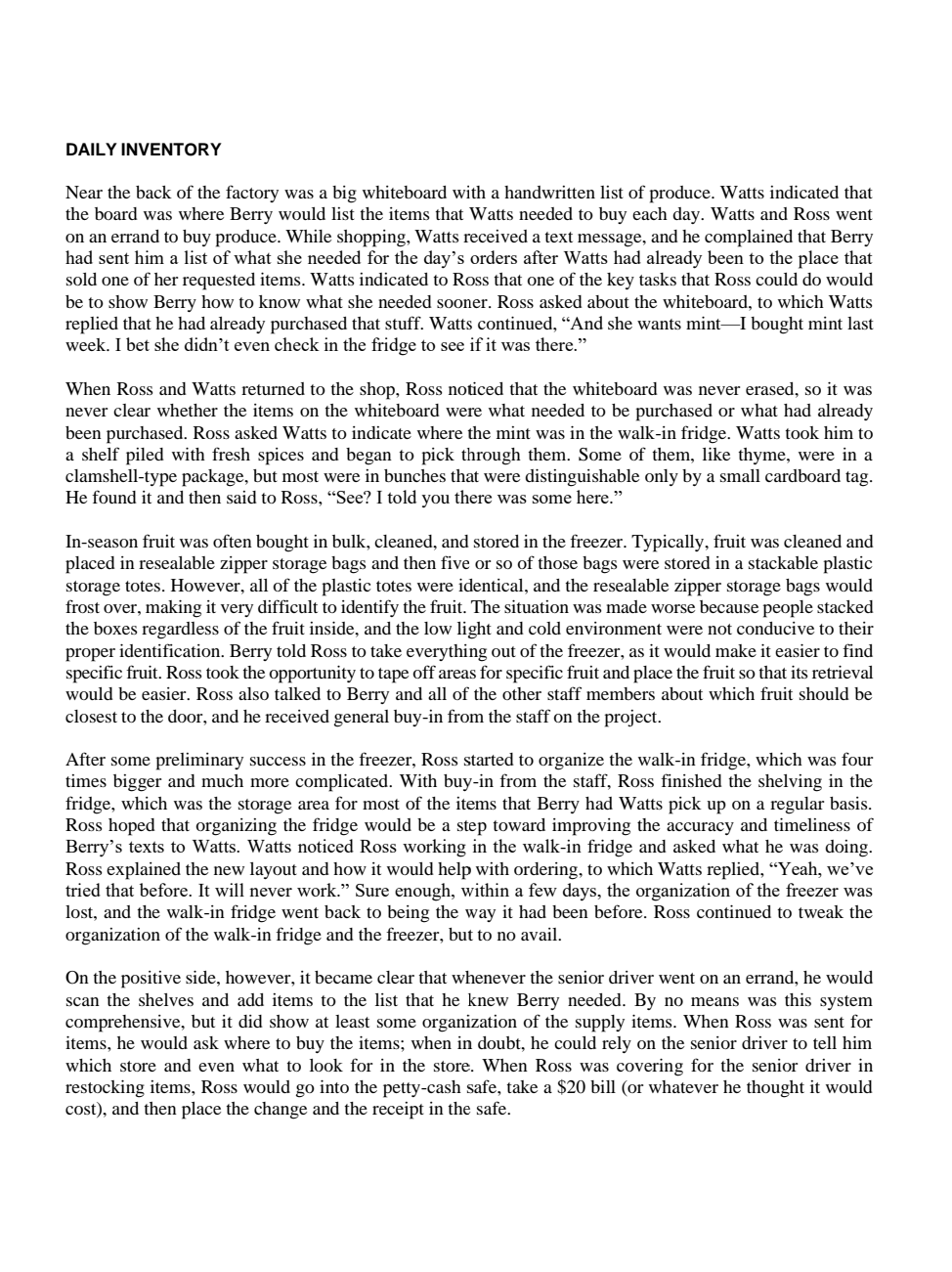

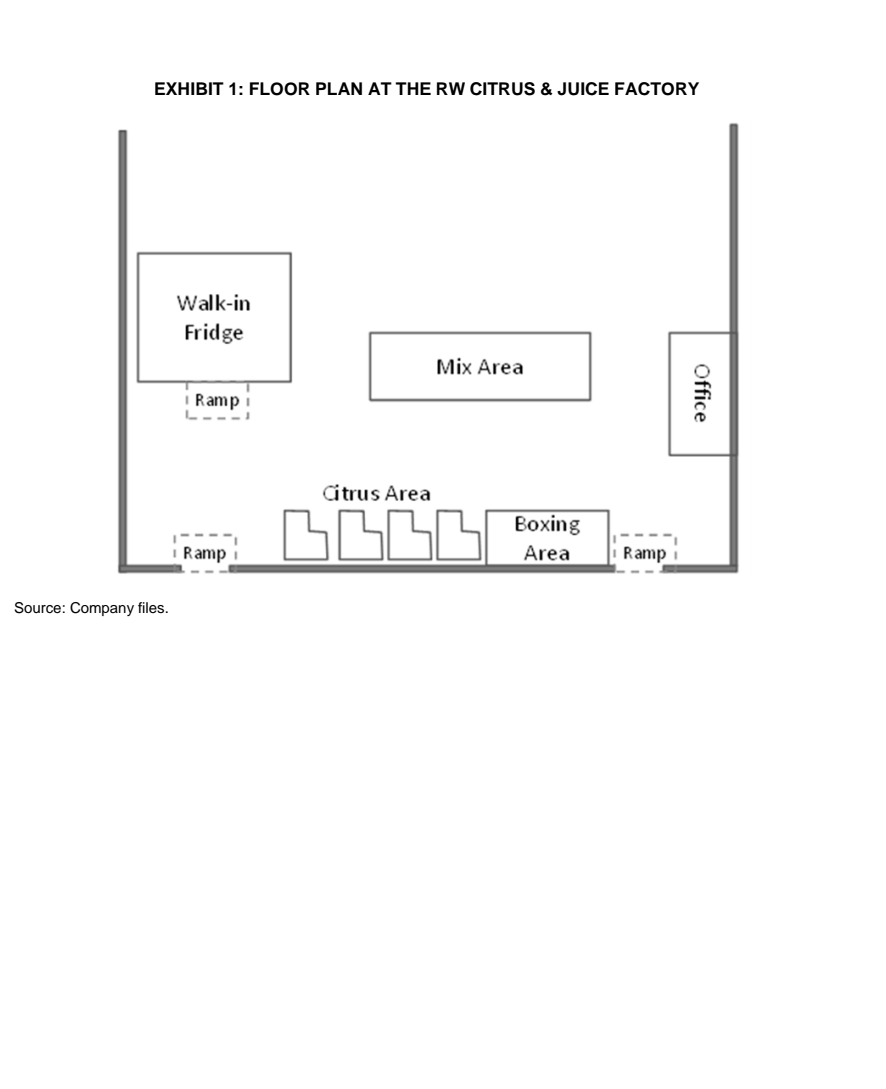

RW CITRUS & JUICE: INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER It was November 19, 2016, and David Ross watched Nadine Berry rush to catch the bus after finishing her Saturday shift and cleanup after the day's juice production at RW Citrus & Juice. Ross was left alone with his thoughts, and he wondered, How was this all going to end? Ross was a management consultant and friend of the owner, Robert Watts, but had been running Watts's company for the past month. Ross had consulted for Watts many times in the past, but this engagement had been much more structured than past engagements and put Ross in the role of running the operations while Watts was away. Ross had observed many opportunities for improving the factory's operations, and in his role as interim general manager, he was well placed to implement those improvements. His concern, however, was that Watts would not accept any of the changes Ross proposed to make. Ross was prepared to quit or be fired when Watts returned on Tuesday, but this past month would have been wasted if Ross did not capture in this (possibly) last report the potential benefits the company could achieve through operational improvements. How should he proceed with his recommendations? BACKGROUND Ross met Watts in 2010, when they lived across the street from each other in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, Michigan. Watts owned RW Citrus & Juice, and when he learned that Ross was a management consultant, Watts opened up about his business. Watts had found that his business made more money selling freshly squeezed juices to restaurants and bars than to passers-by from his retail shop. He then decided to move his operations to a new location that could accommodate more room for his business-to-business (B2B) activities, rather than continue to rent a high-traffic storefront. Although Ross did not know it at the time, Watts fancied himself a risk-taker and had calculated that if hustled, he could make as much as a 40 per cent profit margin from his B2B sales. Ross was happy to consult pro bono (i.e., without charge) when discussing locations and moving issues, but beyond that, Ross was not involved. A few years later, Ross helped Watts with job descriptions and paperwork when Watts needed them to pass some inspections. Watts paid Ross for his time and had made it clear that Ross should do only the minimum necessary to pass the inspections, as Watts would follow up with the additional details later. The inspections were successful, and Ross billed Watts for the time spent. Even though Ross was not in a hurry to receive his money, he was surprised that Watts had dragged out paying the bill for almost a whole year. When they crossed paths after that, they would still talk about the business, and Ross was always happy to give free advice when he could. THE FRESH JUICE INDUSTRY In terms of fresh juice, there were two families of products to consider. The first family was citrus (i.e., oranges, lemons, limes, grapefruits, and tangerines) that were squeezed for their juice and sold to bars and restaurants as freshly squeezed juice. Fresh juice providers loosely competed with national and international players, such as Tropicana Products Inc. and Old South that distributed through grocery stores. The fresh juicers differentiated themselves from the big companies by providing noticeably fresher juice. Freshly squeezed juice deteriorated quickly, so its shelf life ranged from a maximum of between 24 and 48 hours. There were other local fresh juice providers, but most struggled with managing the various demand volumes and seasonal fruit supply. The variabilities in both supply quality and levels of demand tempted juice producers to cut corners by freezing their juice to last a bit longer; however, freezing led both to the jugs deforming, so that they did not sit on the shelf properly, and to the juices separating and stratifying, making the juice unacceptable. The fresh citrus industry was highly fragmented, and although customers liked the stability of one good supplier, they were not above playing one juice provider against another to gain a better price. The second family of products that Watts and his competitors sold was mixed juice, which included any variety of fruit juices (e.g., melon, kiwi, grape, apple, pear, peach, pomegranate, berry, or tropical fruits), vegetable juices (e.g., tomato, carrot, beet, greens, and wheat grass), fresh spices (e.g., ginger, parsley, rosemary, and thyme), and infusions (e.g., teas, saffron, and lavender). The mixed juice segment was also highly fragmented, as products were sold more for their implied health benefits than for the juice itself. High-end restaurants and bars were happy to pay more for fresher product, which helped differentiate their offerings for their foodie customers. However, these restaurants also expected a quick response on orders as well as swift delivery. Typically, the orders were received by 7:00 a.m. and out the door and on the delivery vans by 12:30 p.m. RW Citrus & Juice generated about $5 million' in sales per year and was probably the largest among its local competitors, with 90 per cent of its revenue resulting from direct sales to restaurants. Scale economies on fruit ordering and delivery efficiencies helped Watts stay on top. THE ENGAGEMENT Watts was feeling distracted from the day-to-day squeeze and delivery operations. He was looking at investing in or developing a related business, such as a retail presence in a delicatessen in Bloomfield Hills (a nearby affluent area), where his juice would be paired with sandwiches and other made-to-order dishes. He was also looking into how some of the citrus juices might be squeezed and frozen where the fruit was grown, in South America, and then shipped in bulk. To afford Watts some time to focus on these opportunities, he called on Ross to step in as a general manager for the existing juice business. Watts also felt he was helping Ross, who, at the time, was between jobs. Having some understanding of the business and a consulting background in continuous improvement, Ross also felt that he could make the business more productive in due course. It seemed like a great fit. Watts seemed relieved that after his limited luck trying to hire managers, he had finally found in Ross someone he could trust. 1 All currency amounts are in US$. Given that Ross was not inclined to take a permanent position, he thought it would be best to job shadow the supervisor, Berry, andin an approach typical of consulting coach her in how to see and do things. Ross actually took the role of a worker and performed the tasks that Berry assigned to him. This way, he would not undermine Berry's authority (which he felt was important to retain in lieu of his eventual exit). Also, Ross believed there was value in seeing a business not just from a management perspective but also from the operator's perspective. DELIVERIES Just before Ross and Watts had agreed on the assignment, Ross had been helping Watts by performing some deliveries for the company. The company operated a three-van delivery fleet. When the senior driver mentioned that Ross would use a van that another driver had inaccurately indicated might have faulty brakes, Ross was concerned. The brakes were fine; however, the gas gauge did not work. The next day, Ross asked Watts about getting the gas gauge fixed, to which Watts replied that it was too expensive estimated at $1,000. Ross indicated the need to have reliable delivery vans, to which Watts responded that the drivers did not take care of the vans, and it would be too expensive to fix every little thing that broke. Given their disagreement on the need for investment in van maintenance, Ross requested that deliveries not be a part of his duties for the interim management assignment. THE PRODUCTION PROCESS Ross settled in to focus on the inside operations, where he felt much more comfortable. He mapped all the process steps in the flow of citrus: receiving the skids of citrus, storing the skids in the walk-in fridge, letting the skids warm to room temperature overnight for juicing, juicing, bottling, boxing customer orders, and eventually delivering the juice. The factory was not that big, but it was fairly well laid out (see Exhibit 1.) Similar to the citrus flow process, the mixed juices generally started with ingredients from the walk-in fridge or freezer. However, rather than skids of raw material, the quantities were usually much smaller. Ingredients that were more perishable, such as fresh parsley, strawberries, cucumbers, and bananas, were kept in smaller quantities or were frozen separately in smaller packages after the larger fresh batches were received. The products in the walk-in fridge and freezer and on the shelves totalled nearly 100 stock-keeping units or ingredients to manage. Citrus juices were sold in a large enough volume that every type of citrus juice (e.g., orange, lemon, lime, and grapefruit) was produced daily. After past experiences, when citrus juice went bad before the expiry date, carrying any juice from one day to the next was discouraged. Mixed juice, on the other hand, was always made to order, and it was never clear what products would be needed for the next day's mixed-juice orders. There was no temptation to carry over any work-in-progress inventory. FROM THE BOARD TO THE BOX Order fulfillment began every morning at 7:00 a.m. and was typically complete by 3:00 p.m. Every morning at 7:00 a.m., Berry would start manually writing the daily orders on a sheet of paper (collectively known as "the board). The board listed all the orders for that day, laid out in one place. Berry would start with a photocopy of the standing orders (regular orders that carried over from day to day) and add the current date. She would then skim emails and voice messages for any new orders. She used various short forms on the board to specify the type of juice, such as OJ and Pom (for orange juice and pomegranate juice, respectively), which tended to be easily recognizable, in addition to short forms such as LCP (for lychee cactus pear), which might not have been as common but that everyone internally knew. However, even regulars had a bit of trouble with some terms, such as L for lemonade and LJ for lemon juice. The company did not have a standard way to label lemon juice, so sometimes the full name was written on the label. Berry knew the workers well and tried to make the board unambiguous so that no one would be in a situation to make a mistake. Once all of the orders had been captured, she would make three copies and save the original on the senior driver's desk. One copy would go to citrus, and the other two would go to the respective halves of the mix area to be executed (effectively, one copy was provided to each of the three departments). In each situation, an area lead would highlight the items its area was responsible for producing. In citrus, orange, yellow, green, and pink highlights were used to mark the orders for, respectively, orange juice, lemon juice, lime juice, and grapefruit juice. Next, the total volume of each citrus juice was manually calculated, and the tasks were divided among the workers. Lemonade and other mixed juices were prepared by the mix workers, but they also occasionally requested a pail or two of lemon juice or lime juice from the citrus department to make their mixes. As a point of confusion, some volumes were expressed in metric units, others, in imperial units. Citrus was transported internally in reusable pails. A pail could hold five gallons (equivalent to 20 quarts, or 19 litres), and production orders were usually rounded up to the next pail, theoretically leaving plenty of extra juice for variances in pouring. As production orders were completed, the filled pails would be moved to the filling area, where fillers would manually transfer the juice from the pails to the appropriate jug size. The jugs would then be sealed with a cap that was colour-coded to indicate the contents. The filling area would use the board from the citrus area, but because all of the sums were described in quarts, some mental math was required to determine how many bottles were needed to complete each order. For example, when an order was received for 12 quarts (11 litres) of orange juice with a J next to it, the employees would fill six half gallon jugs. Alternatively, if the next orange juice order was for four quarts with the number 355 next to it, they would fill 12 355-millilitre bottles. For each order, a pen was used to mark on the board which orders had been poured so that no two people completed the same order. In general, the employees would focus on one type of citrus at a time. They would transfer the pails of juice into the appropriate bottles using an empty jug, while trying not to spill any juice. The filled bottles would then go into stand-alone fridges where the drivers would pull juice from to fulfil their orders. Rags were used to sop up the small spills that were inevitable. As each new employee was trained, some discussion occurred as to how high the bottles should be filled, as any fill-level variation was obvious to customers when they received multiple jugs. Thankfully, a senior staff member was usually there to check that the bottles had been filled to the correct height before the locking caps were attached. When the citrus department made the juice faster than it could be bottled, the overflow juice pails were stacked on a cart and stored in the walk-in fridge until the juice could be bottled. However, the employees who acted as fillers were often the least experienced employees in the building, and they sometimes spilled a pail or two when transporting the pail back to the filling area. It was common for someone from the filling table to request more of some type of citrus juice after the citrus department had completed all of their orders and started cleaning their machines. Around 11:00 a.m. each day, the drivers would arrive. The senior driver would divide the orders into various routes, and each driver was responsible for boxing the orders and loading their vans with the boxes. Occasionally, a driver would indicate that part of his order could not be found in the outbound fridges. Sometimes, the juice had been made, but there was a mistake in the labelling; other times, the juice had not been made, and its preparation would need to be expedited. On a good day, the drivers were out by noon. Only about once every two weeks would a driver still be around at 1:00 p.m. After the drivers had gone, the staff occasionally had a bulk order to fill, but invariably the staff would turn their attention to cleaning the machines and the tables. Watts complained to Ross that some employees would drag out how long it took to clean the tables and equipment and how important it was to keep on top of them. He noted one employee who was always quick and thorough and said that he wished all the staff could be like that employee. He then lowered his voice and intimated to Ross: "Do you know how to know it is clean? All you have to do is check the underside of the counter edge, as no one thinks to clean there. If it is clean there, then you know the table has been cleaned properly! CONFUSION ON THE FLOOR All products, except orange juice, were made to a specific recipewhich was in the recipe book that Watts kept as a guarded secret from outsiders. Orange juice was the exception because the recipe would vary depending on which oranges were available and at what price. The company followed agreed-upon blends that would change with the seasons to ensure a juice with the right flavour and an acceptable shelf life. The orange juice blend that the company was using at the time called for two cases of Valencia oranges to one case of navel oranges to maximize flavour and shelf life and minimize fruit cost. Navel oranges were cheaper but had a shorter shelf life. However, all the orange skids in the building were Valencia oranges, as no navel oranges remained. One day, Watts had set up the citrus area and given instructions to not move the skids, as he had placed them in a position that he thought was the most optimal for the operations; however, Ross agreed with the workers in that the arrangement made no sense. The operator changed the layout and worked through the oldest Valencia skids first. Seemingly unrelated, Watts had left a cryptic note for Ross saying that he had found a skid of navel oranges that he had accused the operators of trying to bury in the back of the walk-in fridge. When Watts returned, Ross asked him where the navel oranges were so that they could use them. Watts walked over to the machine, opened a box that said Valencia on it and pulled out an orange. He then said, This is a navel orange. Ross and the operators responded that the box said Valencia, to which Watts responded with, You have to check inside the box! If you cut the orange, you will see that these are navels. Ross then countered that requiring the operators to open every box to slice into an orange to verify its type was not an effective operational strategy and that the label needed to be trusted or edited. In light of the new information, it was clear that the juice produced would not have the desired shelf life. There was then a scramble to unbox one of the orders for a key customer to remix the orange juice before it was shipped. Mixed-juice production occasionally suffered from similar hiccups. For example, Watts noticed more experienced mixers making a sweetened infusion with agave syrup as the sweetener. Watts became quite upset and indicated that the recipe called for simple sugar syrup, which was much cheaper. The employee responded that she was following the recipe and verified it with a recipe from the company web page. Watts had responded that the recipe on the web page was a one-off and was not the "regular" recipe (even though he could not point to the recipe in the recipe book). Watts was much happier when the operator finished the recipe using the cheaper syrup. Watts cited both cases when explaining why Ross needed to be more diligent in managing the company's operations, as Watts did not want to waste such money and create such workaround corrections. DAILY INVENTORY Near the back of the factory was a big whiteboard with a handwritten list of produce. Watts indicated that the board was where Berry would list the items that Watts needed to buy each day. Watts and Ross went on an errand to buy produce. While shopping, Watts received a text message, and he complained that Berry had sent him a list of what she needed for the day's orders after Watts had already been to the place that sold one of her requested items. Watts indicated to Ross that one of the key tasks that Ross could do would be to show Berry how to know what she needed sooner. Ross asked about the whiteboard, to which Watts replied that he had already purchased that stuff. Watts continued, And she wants mint I bought mint last week. I bet she didn't even check in the fridge to see if it was there. When Ross and Watts returned to the shop, Ross noticed that the whiteboard was never erased, so it was never clear whether the items on the whiteboard were what needed to be purchased or what had already been purchased. Ross asked Watts to indicate where the mint was in the walk-in fridge. Watts took him to a shelf piled with fresh spices and began to pick through them. Some of them, like thyme, were in a clamshell-type package, but most were in bunches that were distinguishable only by a small cardboard tag. He found it and then said to Ross, See? I told you there was some here." In-season fruit was often bought in bulk, cleaned, and stored in the freezer. Typically, fruit was cleaned and placed in resealable zipper storage bags and then five or so of those bags were stored in a stackable plastic storage totes. However, all of the plastic totes were identical, and the resealable zipper storage bags would frost over, making it very difficult to identify the fruit. The situation was made worse because people stacked the boxes regardless of the fruit inside, and the low light and cold environment were not conducive to their proper identification. Berry told Ross to take everything out of the freezer, as it would make it easier to find specific fruit. Ross took the opportunity to tape off areas for specific fruit and place the fruit so that its retrieval would be easier. Ross also talked to Berry and all of the other staff members about which fruit should be closest to the door, and he received general buy-in from the staff on the project. After some preliminary success in the freezer, Ross started to organize the walk-in fridge, which was four times bigger and much more complicated. With buy-in from the staff, Ross finished the shelving in the fridge, which was the storage area for most of the items that Berry had Watts pick up on a regular basis. Ross hoped that organizing the fridge would be a step toward improving the accuracy and timeliness of Berry's texts to Watts. Watts noticed Ross working in the walk-in fridge and asked what he was doing. Ross explained the new layout and how it would help with ordering, to which Watts replied, Yeah, we've tried that before. It will never work. Sure enough, within a few days, the organization of the freezer was lost, and the walk-in fridge went back to being the way it had been before. Ross continued to tweak the organization of the walk-in fridge and the freezer, but to no avail. On the positive side, however, it became clear that whenever the senior driver went on an errand, he would scan the shelves and add items to the list that he knew Berry needed. By no means was this system comprehensive, but it did show at least some organization of the supply items. When Ross was sent for items, he would ask where to buy the items; when in doubt, he could rely on the senior driver to tell him which store and even what to look for in the store. When Ross was covering for the senior driver in restocking items, Ross would go into the petty-cash safe, take a $20 bill (or whatever he thought it would cost), and then place the change and the receipt in the safe. WATTS GOES AWAY Watts had a trip scheduled, and he planned to leave Ross in charge. In advance of the trip, Watts indicated to Ross that $2,000 would be in the petty cash safe for supplies needed during the week. Ross indicated that $2,000 seemed like a lot of money, but he welcomed whatever Watts wanted to do to ensure that at least a couple hundred dollars were available each day. Later, the comptroller had scoffed that $2,000 was a bit much to leave all at once, and she decided to put in sufficient daily amounts. Ross was fine with the arrangement, restating that the only requirement was that he had enough each day for what he needed to buy for production. Leading up to the weekend before Watts left, one of the delivery vans experienced trouble; with Watt's blessing, Ross had the senior driver leave it with the mechanic. However, on the Sunday Watts was leaving, Ross received a text message from Watts stating that one of Watts's friends would be borrowing one of the delivery vans. Ross shot back a text message stating that one van was already with the mechanic, so losing a second van could compromise deliveries, and that Watts should reconsider. Ross did not receive a response, and when he arrived at the company on the Monday, he realized that the van had already been taken. key until Ross also realized that the walk-in fridge door and freezer were locked and that nobody had Berry arrived half an hour later. DAY ONE Berry gave Ross the list of items she needed for that day, and when Ross went to the safe for $50 to cover the cost of the items, he found only $2.50. Ross left a message for Watts. When Watts returned his call about an hour later, he asked what was on the list. Ross read the list, and when he got to frozen pineapple, Watts retorted, "I just bought frozen pineapple. There should be 10 five-pound bags in the freezer. Ross replied with the exact quantity of frozen pineapple they had and the amount they expected to need for the orders. Even though Watts knew the importance of the schedule, he seemed less interested in getting the orders out than he was in understanding whether someone was stealing the frozen pineapple. Ross retorted that theft or no theft, the orders needed to be prepared. Watts still insisted that Ross send him a list of all orders that included pineapple in the previous three days so that Watts could understand where the pineapple had gone. Ross sent the data Watts wanted. While waiting for a response, the senior driver offered to try to buy what was needed on credit through one of the preferred suppliers so that part of the $50 would not be needed right away. Ross agreed that such an arrangement would help greatly. When the comptroller arrived, Ross asked for the promised money for petty cash. The comptroller indicated that she did not have it and then turned to ignore Ross. Rather than waste time fighting, Ross left another message for Watts and went to the back to see whether he could move the production along to meet the looming noon deadline. Although the money had not yet arrived, Ross breathed a sigh of relief and began shepherding the last few bulk orders. When Watts called back with further accusations about stealing, Ross was just sending off the last driver. Ross again asked about the petty-cash situation, and Watts indicated that he had also left two blank cheques made out to the preferred supplier in case they were needed. However, he had left only two cheques, and they were both locked in the office for which only the comptroller had a key. Ross was happy to get the orders out on time. He redirected the internal staff to start some prep for a bulk order. As they were cleaning up, Ross received a text message from Watts indicating his concerns about some rumours he was hearing from staff about Ross's management style. This was the last straw for Ross. He went home and crafted a text message response, indicating that he felt Watts and the comptroller were either purposely or inadvertently trying to sabotage Ross's week as a manager. Ross was happy to meet the obligation to get through the week, and he did not want to leave Watts high and dry, but he knew that he could not put up with such unprofessionalism. Watts was letting unsubstantiated rumours influence him, and Ross wondered, What kind of a boss, after having put up security cameras and night locks on the fridges and freezers, concerns himself with accusation of theft regarding $70 worth of frozen pineapple while he is 1,000 miles away? Watts immediately called Ross and was conciliatory. Although he did not qualify his statements, Watts affirmed that no one was trying to sabotage Ross's management term. DAY TWO On the second day, the freezer did not work. Ross scrambled to find the slip of paper on which Watts had indicated where he kept the phone numbers for repair companies. Ross called the repair company and left his cell phone number on the answering machine. THE REST OF THE WEEK The rest of the week went similarly: some suppliers of citrus showed up at the dock with produce but uncharacteristically demanded a cheque before unloading. This delay was often cleared up after a phone call to Watts but would nevertheless eat into the time Ross should have been doing other things. The comptroller was being very stingy with cash, and every time Ross explained the situation to Watts, Ross would cite examples of the comptroller's lack of co-operation and how it was not conducive to running the business profitably. On the weekend, an order was received for cashew milk, but there was no stock of cashews. The senior driver and Ross agreed that even though they often ordered cashews from the supplier who previously extended them credit, it was not worth using up the last cheque they had in reserve and a special trip just for a bag of cashews, so the senior driver picked up some cashews where he was picking up another product. Later that day, when Ross made his daily call to Watts to have money cleared from the comptroller for gas and supplies, Watts asked what they had used the rest of the money for. When Ross mentioned the cashews, Watts started on a tirade about how much more the cashews cost at other stores and how the senior driver should have known better than to buy cashews anywhere else. Despite Ross indicating that he supported the senior driver in the decision and that the price of the cashews was not the only factor, Watts went on about how the cashew milk was now going to be sold at a loss (although a quick calculation would have clearly shown a profit) and how nobody in the shop cared about how much things cost. Watts talked for about 10 minutes just about the cashews. THE LAST DAY Watts would be back on the following Tuesday, and Ross was proud of his record: the orders had been out on time every day, and the payroll for the week was lower than what had been budgeted. Those successes notwithstanding, Ross knew he would not be comfortable working with Watts and his comptroller under the current mode of operations. He knew that he had to present an ultimatum to Watts regarding what was required to improve operations. Doing so relied heavily on how Ross would articulate in his report to Watts what needed to be changed. When Ross had started the interim position, he had thought that if he could initiate some of the changes, the business could show significant improvementalbeit slowly. Now, however, Ross was certain that the EXHIBIT 1: FLOOR PLAN AT THE RW CITRUS & JUICE FACTORY Walk-in Fridge Mix Area Ramp Office atrus Area Boxing Area Ramp Ramp Source: Company files. RW CITRUS & JUICE: INTERIM GENERAL MANAGER It was November 19, 2016, and David Ross watched Nadine Berry rush to catch the bus after finishing her Saturday shift and cleanup after the day's juice production at RW Citrus & Juice. Ross was left alone with his thoughts, and he wondered, How was this all going to end? Ross was a management consultant and friend of the owner, Robert Watts, but had been running Watts's company for the past month. Ross had consulted for Watts many times in the past, but this engagement had been much more structured than past engagements and put Ross in the role of running the operations while Watts was away. Ross had observed many opportunities for improving the factory's operations, and in his role as interim general manager, he was well placed to implement those improvements. His concern, however, was that Watts would not accept any of the changes Ross proposed to make. Ross was prepared to quit or be fired when Watts returned on Tuesday, but this past month would have been wasted if Ross did not capture in this (possibly) last report the potential benefits the company could achieve through operational improvements. How should he proceed with his recommendations? BACKGROUND Ross met Watts in 2010, when they lived across the street from each other in the Detroit suburb of Royal Oak, Michigan. Watts owned RW Citrus & Juice, and when he learned that Ross was a management consultant, Watts opened up about his business. Watts had found that his business made more money selling freshly squeezed juices to restaurants and bars than to passers-by from his retail shop. He then decided to move his operations to a new location that could accommodate more room for his business-to-business (B2B) activities, rather than continue to rent a high-traffic storefront. Although Ross did not know it at the time, Watts fancied himself a risk-taker and had calculated that if hustled, he could make as much as a 40 per cent profit margin from his B2B sales. Ross was happy to consult pro bono (i.e., without charge) when discussing locations and moving issues, but beyond that, Ross was not involved. A few years later, Ross helped Watts with job descriptions and paperwork when Watts needed them to pass some inspections. Watts paid Ross for his time and had made it clear that Ross should do only the minimum necessary to pass the inspections, as Watts would follow up with the additional details later. The inspections were successful, and Ross billed Watts for the time spent. Even though Ross was not in a hurry to receive his money, he was surprised that Watts had dragged out paying the bill for almost a whole year. When they crossed paths after that, they would still talk about the business, and Ross was always happy to give free advice when he could. THE FRESH JUICE INDUSTRY In terms of fresh juice, there were two families of products to consider. The first family was citrus (i.e., oranges, lemons, limes, grapefruits, and tangerines) that were squeezed for their juice and sold to bars and restaurants as freshly squeezed juice. Fresh juice providers loosely competed with national and international players, such as Tropicana Products Inc. and Old South that distributed through grocery stores. The fresh juicers differentiated themselves from the big companies by providing noticeably fresher juice. Freshly squeezed juice deteriorated quickly, so its shelf life ranged from a maximum of between 24 and 48 hours. There were other local fresh juice providers, but most struggled with managing the various demand volumes and seasonal fruit supply. The variabilities in both supply quality and levels of demand tempted juice producers to cut corners by freezing their juice to last a bit longer; however, freezing led both to the jugs deforming, so that they did not sit on the shelf properly, and to the juices separating and stratifying, making the juice unacceptable. The fresh citrus industry was highly fragmented, and although customers liked the stability of one good supplier, they were not above playing one juice provider against another to gain a better price. The second family of products that Watts and his competitors sold was mixed juice, which included any variety of fruit juices (e.g., melon, kiwi, grape, apple, pear, peach, pomegranate, berry, or tropical fruits), vegetable juices (e.g., tomato, carrot, beet, greens, and wheat grass), fresh spices (e.g., ginger, parsley, rosemary, and thyme), and infusions (e.g., teas, saffron, and lavender). The mixed juice segment was also highly fragmented, as products were sold more for their implied health benefits than for the juice itself. High-end restaurants and bars were happy to pay more for fresher product, which helped differentiate their offerings for their foodie customers. However, these restaurants also expected a quick response on orders as well as swift delivery. Typically, the orders were received by 7:00 a.m. and out the door and on the delivery vans by 12:30 p.m. RW Citrus & Juice generated about $5 million' in sales per year and was probably the largest among its local competitors, with 90 per cent of its revenue resulting from direct sales to restaurants. Scale economies on fruit ordering and delivery efficiencies helped Watts stay on top. THE ENGAGEMENT Watts was feeling distracted from the day-to-day squeeze and delivery operations. He was looking at investing in or developing a related business, such as a retail presence in a delicatessen in Bloomfield Hills (a nearby affluent area), where his juice would be paired with sandwiches and other made-to-order dishes. He was also looking into how some of the citrus juices might be squeezed and frozen where the fruit was grown, in South America, and then shipped in bulk. To afford Watts some time to focus on these opportunities, he called on Ross to step in as a general manager for the existing juice business. Watts also felt he was helping Ross, who, at the time, was between jobs. Having some understanding of the business and a consulting background in continuous improvement, Ross also felt that he could make the business more productive in due course. It seemed like a great fit. Watts seemed relieved that after his limited luck trying to hire managers, he had finally found in Ross someone he could trust. 1 All currency amounts are in US$. Given that Ross was not inclined to take a permanent position, he thought it would be best to job shadow the supervisor, Berry, andin an approach typical of consulting coach her in how to see and do things. Ross actually took the role of a worker and performed the tasks that Berry assigned to him. This way, he would not undermine Berry's authority (which he felt was important to retain in lieu of his eventual exit). Also, Ross believed there was value in seeing a business not just from a management perspective but also from the operator's perspective. DELIVERIES Just before Ross and Watts had agreed on the assignment, Ross had been helping Watts by performing some deliveries for the company. The company operated a three-van delivery fleet. When the senior driver mentioned that Ross would use a van that another driver had inaccurately indicated might have faulty brakes, Ross was concerned. The brakes were fine; however, the gas gauge did not work. The next day, Ross asked Watts about getting the gas gauge fixed, to which Watts replied that it was too expensive estimated at $1,000. Ross indicated the need to have reliable delivery vans, to which Watts responded that the drivers did not take care of the vans, and it would be too expensive to fix every little thing that broke. Given their disagreement on the need for investment in van maintenance, Ross requested that deliveries not be a part of his duties for the interim management assignment. THE PRODUCTION PROCESS Ross settled in to focus on the inside operations, where he felt much more comfortable. He mapped all the process steps in the flow of citrus: receiving the skids of citrus, storing the skids in the walk-in fridge, letting the skids warm to room temperature overnight for juicing, juicing, bottling, boxing customer orders, and eventually delivering the juice. The factory was not that big, but it was fairly well laid out (see Exhibit 1.) Similar to the citrus flow process, the mixed juices generally started with ingredients from the walk-in fridge or freezer. However, rather than skids of raw material, the quantities were usually much smaller. Ingredients that were more perishable, such as fresh parsley, strawberries, cucumbers, and bananas, were kept in smaller quantities or were frozen separately in smaller packages after the larger fresh batches were received. The products in the walk-in fridge and freezer and on the shelves totalled nearly 100 stock-keeping units or ingredients to manage. Citrus juices were sold in a large enough volume that every type of citrus juice (e.g., orange, lemon, lime, and grapefruit) was produced daily. After past experiences, when citrus juice went bad before the expiry date, carrying any juice from one day to the next was discouraged. Mixed juice, on the other hand, was always made to order, and it was never clear what products would be needed for the next day's mixed-juice orders. There was no temptation to carry over any work-in-progress inventory. FROM THE BOARD TO THE BOX Order fulfillment began every morning at 7:00 a.m. and was typically complete by 3:00 p.m. Every morning at 7:00 a.m., Berry would start manually writing the daily orders on a sheet of paper (collectively known as "the board). The board listed all the orders for that day, laid out in one place. Berry would start with a photocopy of the standing orders (regular orders that carried over from day to day) and add the current date. She would then skim emails and voice messages for any new orders. She used various short forms on the board to specify the type of juice, such as OJ and Pom (for orange juice and pomegranate juice, respectively), which tended to be easily recognizable, in addition to short forms such as LCP (for lychee cactus pear), which might not have been as common but that everyone internally knew. However, even regulars had a bit of trouble with some terms, such as L for lemonade and LJ for lemon juice. The company did not have a standard way to label lemon juice, so sometimes the full name was written on the label. Berry knew the workers well and tried to make the board unambiguous so that no one would be in a situation to make a mistake. Once all of the orders had been captured, she would make three copies and save the original on the senior driver's desk. One copy would go to citrus, and the other two would go to the respective halves of the mix area to be executed (effectively, one copy was provided to each of the three departments). In each situation, an area lead would highlight the items its area was responsible for producing. In citrus, orange, yellow, green, and pink highlights were used to mark the orders for, respectively, orange juice, lemon juice, lime juice, and grapefruit juice. Next, the total volume of each citrus juice was manually calculated, and the tasks were divided among the workers. Lemonade and other mixed juices were prepared by the mix workers, but they also occasionally requested a pail or two of lemon juice or lime juice from the citrus department to make their mixes. As a point of confusion, some volumes were expressed in metric units, others, in imperial units. Citrus was transported internally in reusable pails. A pail could hold five gallons (equivalent to 20 quarts, or 19 litres), and production orders were usually rounded up to the next pail, theoretically leaving plenty of extra juice for variances in pouring. As production orders were completed, the filled pails would be moved to the filling area, where fillers would manually transfer the juice from the pails to the appropriate jug size. The jugs would then be sealed with a cap that was colour-coded to indicate the contents. The filling area would use the board from the citrus area, but because all of the sums were described in quarts, some mental math was required to determine how many bottles were needed to complete each order. For example, when an order was received for 12 quarts (11 litres) of orange juice with a J next to it, the employees would fill six half gallon jugs. Alternatively, if the next orange juice order was for four quarts with the number 355 next to it, they would fill 12 355-millilitre bottles. For each order, a pen was used to mark on the board which orders had been poured so that no two people completed the same order. In general, the employees would focus on one type of citrus at a time. They would transfer the pails of juice into the appropriate bottles using an empty jug, while trying not to spill any juice. The filled bottles would then go into stand-alone fridges where the drivers would pull juice from to fulfil their orders. Rags were used to sop up the small spills that were inevitable. As each new employee was trained, some discussion occurred as to how high the bottles should be filled, as any fill-level variation was obvious to customers when they received multiple jugs. Thankfully, a senior staff member was usually there to check that the bottles had been filled to the correct height before the locking caps were attached. When the citrus department made the juice faster than it could be bottled, the overflow juice pails were stacked on a cart and stored in the walk-in fridge until the juice could be bottled. However, the employees who acted as fillers were often the least experienced employees in the building, and they sometimes spilled a pail or two when transporting the pail back to the filling area. It was common for someone from the filling table to request more of some type of citrus juice after the citrus department had completed all of their orders and started cleaning their machines. Around 11:00 a.m. each day, the drivers would arrive. The senior driver would divide the orders into various routes, and each driver was responsible for boxing the orders and loading their vans with the boxes. Occasionally, a driver would indicate that part of his order could not be found in the outbound fridges. Sometimes, the juice had been made, but there was a mistake in the labelling; other times, the juice had not been made, and its preparation would need to be expedited. On a good day, the drivers were out by noon. Only about once every two weeks would a driver still be around at 1:00 p.m. After the drivers had gone, the staff occasionally had a bulk order to fill, but invariably the staff would turn their attention to cleaning the machines and the tables. Watts complained to Ross that some employees would drag out how long it took to clean the tables and equipment and how important it was to keep on top of them. He noted one employee who was always quick and thorough and said that he wished all the staff could be like that employee. He then lowered his voice and intimated to Ross: "Do you know how to know it is clean? All you have to do is check the underside of the counter edge, as no one thinks to clean there. If it is clean there, then you know the table has been cleaned properly! CONFUSION ON THE FLOOR All products, except orange juice, were made to a specific recipewhich was in the recipe book that Watts kept as a guarded secret from outsiders. Orange juice was the exception because the recipe would vary depending on which oranges were available and at what price. The company followed agreed-upon blends that would change with the seasons to ensure a juice with the right flavour and an acceptable shelf life. The orange juice blend that the company was using at the time called for two cases of Valencia oranges to one case of navel oranges to maximize flavour and shelf life and minimize fruit cost. Navel oranges were cheaper but had a shorter shelf life. However, all the orange skids in the building were Valencia oranges, as no navel oranges remained. One day, Watts had set up the citrus area and given instructions to not move the skids, as he had placed them in a position that he thought was the most optimal for the operations; however, Ross agreed with the workers in that the arrangement made no sense. The operator changed the layout and worked through the oldest Valencia skids first. Seemingly unrelated, Watts had left a cryptic note for Ross saying that he had found a skid of navel oranges that he had accused the operators of trying to bury in the back of the walk-in fridge. When Watts returned, Ross asked him where the navel oranges were so that they could use them. Watts walked over to the machine, opened a box that said Valencia on it and pulled out an orange. He then said, This is a navel orange. Ross and the operators responded that the box said Valencia, to which Watts responded with, You have to check inside the box! If you cut the orange, you will see that these are navels. Ross then countered that requiring the operators to open every box to slice into an orange to verify its type was not an effective operational strategy and that the label needed to be trusted or edited. In light of the new information, it was clear that the juice produced would not have the desired shelf life. There was then a scramble to unbox one of the orders for a key customer to remix the orange juice before it was shipped. Mixed-juice production occasionally suffered from similar hiccups. For example, Watts noticed more experienced mixers making a sweetened infusion with agave syrup as the sweetener. Watts became quite upset and indicated that the recipe called for simple sugar syrup, which was much cheaper. The employee responded that she was following the recipe and verified it with a recipe from the company web page. Watts had responded that the recipe on the web page was a one-off and was not the "regular" recipe (even though he could not point to the recipe in the recipe book). Watts was much happier when the operator finished the recipe using the cheaper syrup. Watts cited both cases when explaining why Ross needed to be more diligent in managing the company's operations, as Watts did not want to waste such money and create such workaround corrections. DAILY INVENTORY Near the back of the factory was a big whiteboard with a handwritten list of produce. Watts indicated that the board was where Berry would list the items that Watts needed to buy each day. Watts and Ross went on an errand to buy produce. While shopping, Watts received a text message, and he complained that Berry had sent him a list of what she needed for the day's orders after Watts had already been to the place that sold one of her requested items. Watts indicated to Ross that one of the key tasks that Ross could do would be to show Berry how to know what she needed sooner. Ross asked about the whiteboard, to which Watts replied that he had already purchased that stuff. Watts continued, And she wants mint I bought mint last week. I bet she didn't even check in the fridge to see if it was there. When Ross and Watts returned to the shop, Ross noticed that the whiteboard was never erased, so it was never clear whether the items on the whiteboard were what needed to be purchased or what had already been purchased. Ross asked Watts to indicate where the mint was in the walk-in fridge. Watts took him to a shelf piled with fresh spices and began to pick through them. Some of them, like thyme, were in a clamshell-type package, but most were in bunches that were distinguishable only by a small cardboard tag. He found it and then said to Ross, See? I told you there was some here." In-season fruit was often bought in bulk, cleaned, and stored in the freezer. Typically, fruit was cleaned and placed in resealable zipper storage bags and then five or so of those bags were stored in a stackable plastic storage totes. However, all of the plastic totes were identical, and the resealable zipper storage bags would frost over, making it very difficult to identify the fruit. The situation was made worse because people stacked the boxes regardless of the fruit inside, and the low light and cold environment were not conducive to their proper identification. Berry told Ross to take everything out of the freezer, as it would make it easier to find specific fruit. Ross took the opportunity to tape off areas for specific fruit and place the fruit so that its retrieval would be easier. Ross also talked to Berry and all of the other staff members about which fruit should be closest to the door, and he received general buy-in from the staff on the project. After some preliminary success in the freezer, Ross started to organize the walk-in fridge, which was four times bigger and much more complicated. With buy-in from the staff, Ross finished the shelving in the fridge, which was the storage area for most of the items that Berry had Watts pick up on a regular basis. Ross hoped that organizing the fridge would be a step toward improving the accuracy and timeliness of Berry's texts to Watts. Watts noticed Ross working in the walk-in fridge and asked what he was doing. Ross explained the new layout and how it would help with ordering, to which Watts replied, Yeah, we've tried that before. It will never work. Sure enough, within a few days, the organization of the freezer was lost, and the walk-in fridge went back to being the way it had been before. Ross continued to tweak the organization of the walk-in fridge and the freezer, but to no avail. On the positive side, however, it became clear that whenever the senior driver went on an errand, he would scan the shelves and add items to the list that he knew Berry needed. By no means was this system comprehensive, but it did show at least some organization of the supply items. When Ross was sent for items, he would ask where to buy the items; when in doubt, he could rely on the senior driver to tell him which store and even what to look for in the store. When Ross was covering for the senior driver in restocking items, Ross would go into the petty-cash safe, take a $20 bill (or whatever he thought it would cost), and then place the change and the receipt in the safe. WATTS GOES AWAY Watts had a trip scheduled, and he planned to leave Ross in charge. In advance of the trip, Watts indicated to Ross that $2,000 would be in the petty cash safe for supplies needed during the week. Ross indicated that $2,000 seemed like a lot of money, but he welcomed whatever Watts wanted to do to ensure that at least a couple hundred dollars were available each day. Later, the comptroller had scoffed that $2,000 was a bit much to leave all at once, and she decided to put in sufficient daily amounts. Ross was fine with the arrangement, restating that the only requirement was that he had enough each day for what he needed to buy for production. Leading up to the weekend before Watts left, one of the delivery vans experienced trouble; with Watt's blessing, Ross had the senior driver leave it with the mechanic. However, on the Sunday Watts was leaving, Ross received a text message from Watts stating that one of Watts's friends would be borrowing one of the delivery vans. Ross shot back a text message stating that one van was already with the mechanic, so losing a second van could compromise deliveries, and that Watts should reconsider. Ross did not receive a response, and when he arrived at the company on the Monday, he realized that the van had already been taken. key until Ross also realized that the walk-in fridge door and freezer were locked and that nobody had Berry arrived half an hour later. DAY ONE Berry gave Ross the list of items she needed for that day, and when Ross went to the safe for $50 to cover the cost of the items, he found only $2.50. Ross left a message for Watts. When Watts returned his call about an hour later, he asked what was on the list. Ross read the list, and when he got to frozen pineapple, Watts retorted, "I just bought frozen pineapple. There should be 10 five-pound bags in the freezer. Ross replied with the exact quantity of frozen pineapple they had and the amount they expected to need for the orders. Even though Watts knew the importance of the schedule, he seemed less interested in getting the orders out than he was in understanding whether someone was stealing the frozen pineapple. Ross retorted that theft or no theft, the orders needed to be prepared. Watts still insisted that Ross send him a list of all orders that included pineapple in the previous three days so that Watts could understand where the pineapple had gone. Ross sent the data Watts wanted. While waiting for a response, the senior driver offered to try to buy what was needed on credit through one of the preferred suppliers so that part of the $50 would not be needed right away. Ross agreed that such an arrangement would help greatly. When the comptroller arrived, Ross asked for the promised money for petty cash. The comptroller indicated that she did not have it and then turned to ignore Ross. Rather than waste time fighting, Ross left another message for Watts and went to the back to see whether he could move the production along to meet the looming noon deadline. Although the money had not yet arrived, Ross breathed a sigh of relief and began shepherding the last few bulk orders. When Watts called back with further accusations about stealing, Ross was just sending off the last driver. Ross again asked about the petty-cash situation, and Watts indicated that he had also left two blank cheques made out to the preferred supplier in case they were needed. However, he had left only two cheques, and they were both locked in the office for which only the comptroller had a key. Ross was happy to get the orders out on time. He redirected the internal staff to start some prep for a bulk order. As they were cleaning up, Ross received a text message from Watts indicating his concerns about some rumours he was hearing from staff about Ross's management style. This was the last straw for Ross. He went home and crafted a text message response, indicating that he felt Watts and the comptroller were either purposely or inadvertently trying to sabotage Ross's week as a manager. Ross was happy to meet the obligation to get through the week, and he did not want to leave Watts high and dry, but he knew that he could not put up with such unprofessionalism. Watts was letting unsubstantiated rumours influence him, and Ross wondered, What kind of a boss, after having put up security cameras and night locks on the fridges and freezers, concerns himself with accusation of theft regarding $70 worth of frozen pineapple while he is 1,000 miles away? Watts immediately called Ross and was conciliatory. Although he did not qualify his statements, Watts affirmed that no one was trying to sabotage Ross's management term. DAY TWO On the second day, the freezer did not work. Ross scrambled to find the slip of paper on which Watts had indicated where he kept the phone numbers for repair companies. Ross called the repair company and left his cell phone number on the answering machine. THE REST OF THE WEEK The rest of the week went similarly: some suppliers of citrus showed up at the dock with produce but uncharacteristically demanded a cheque before unloading. This delay was often cleared up after a phone call to Watts but would nevertheless eat into the time Ross should have been doing other things. The comptroller was being very stingy with cash, and every time Ross explained the situation to Watts, Ross would cite examples of the comptroller's lack of co-operation and how it was not conducive to running the business profitably. On the weekend, an order was received for cashew milk, but there was no stock of cashews. The senior driver and Ross agreed that even though they often ordered cashews from the supplier who previously extended them credit, it was not worth using up the last cheque they had in reserve and a special trip just for a bag of cashews, so the senior driver picked up some cashews where he was picking up another product. Later that day, when Ross made his daily call to Watts to have money cleared from the comptroller for gas and supplies, Watts asked what they had used the rest of the money for. When Ross mentioned the cashews, Watts started on a tirade about how much more the cashews cost at other stores and how the senior driver should have known better than to buy cashews anywhere else. Despite Ross indicating that he supported the senior driver in the decision and that the price of the cashews was not the only factor, Watts went on about how the cashew milk was now going to be sold at a loss (although a quick calculation would have clearly shown a profit) and how nobody in the shop cared about how much things cost. Watts talked for about 10 minutes just about the cashews. THE LAST DAY Watts would be back on the following Tuesday, and Ross was proud of his record: the orders had been out on time every day, and the payroll for the week was lower than what had been budgeted. Those successes notwithstanding, Ross knew he would not be comfortable working with Watts and his comptroller under the current mode of operations. He knew that he had to present an ultimatum to Watts regarding what was required to improve operations. Doing so relied heavily on how Ross would articulate in his report to Watts what needed to be changed. When Ross had started the interim position, he had thought that if he could initiate some of the changes, the business could show significant improvementalbeit slowly. Now, however, Ross was certain that the EXHIBIT 1: FLOOR PLAN AT THE RW CITRUS & JUICE FACTORY Walk-in Fridge Mix Area Ramp Office atrus Area Boxing Area Ramp Ramp Source: Company filesStep by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Step: 1

Get Instant Access to Expert-Tailored Solutions

See step-by-step solutions with expert insights and AI powered tools for academic success

Step: 2

Step: 3

Ace Your Homework with AI

Get the answers you need in no time with our AI-driven, step-by-step assistance

Get Started