Question: 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Questions: 1. Matching customer demand to production scheduling is a crucial

2

2

3 4

4

5 6

6

7 8

8

9 10

10

11 12

12

13 14

14

15![[globally] in pharmaceuticals, number one in crop protection, and has tremendous development](https://dsd5zvtm8ll6.cloudfront.net/si.experts.images/questions/2024/10/671cae3c3b437_859671cae3b8a146.jpg)

Questions:

1. Matching customer demand to production scheduling is a crucial activity for any company. Explain why this was problematic for Geneva.

2. Describe Genevas IT infrastructure before the SAP/R3 implementation and what problems were caused by it.

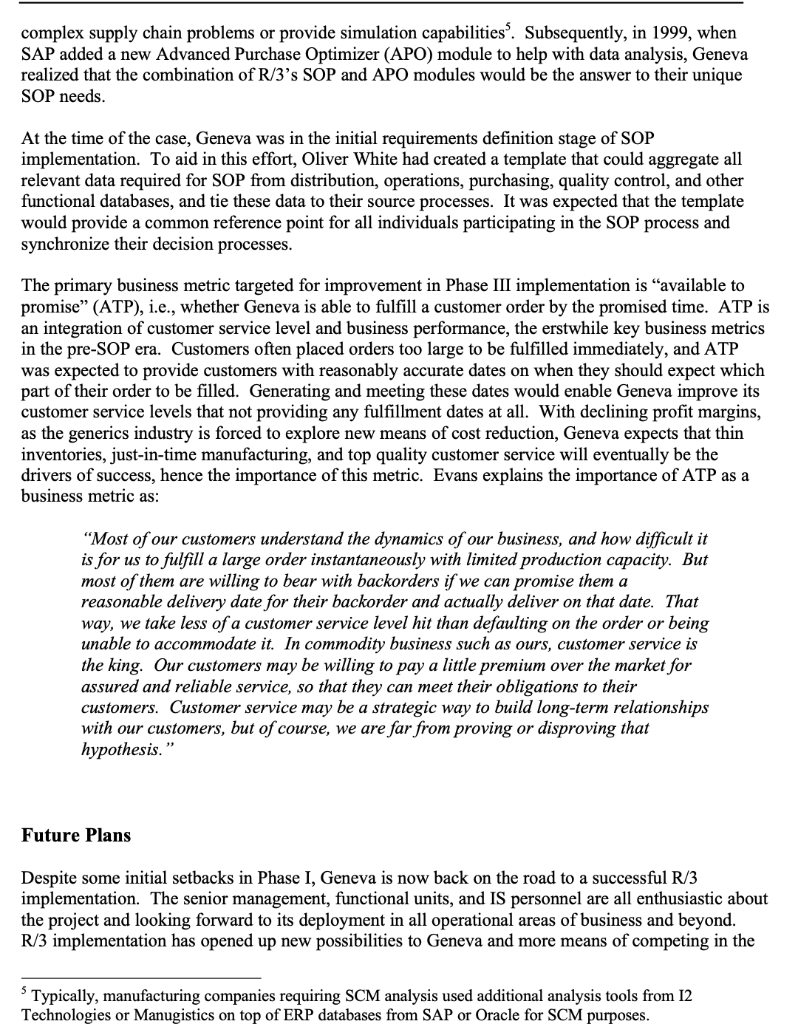

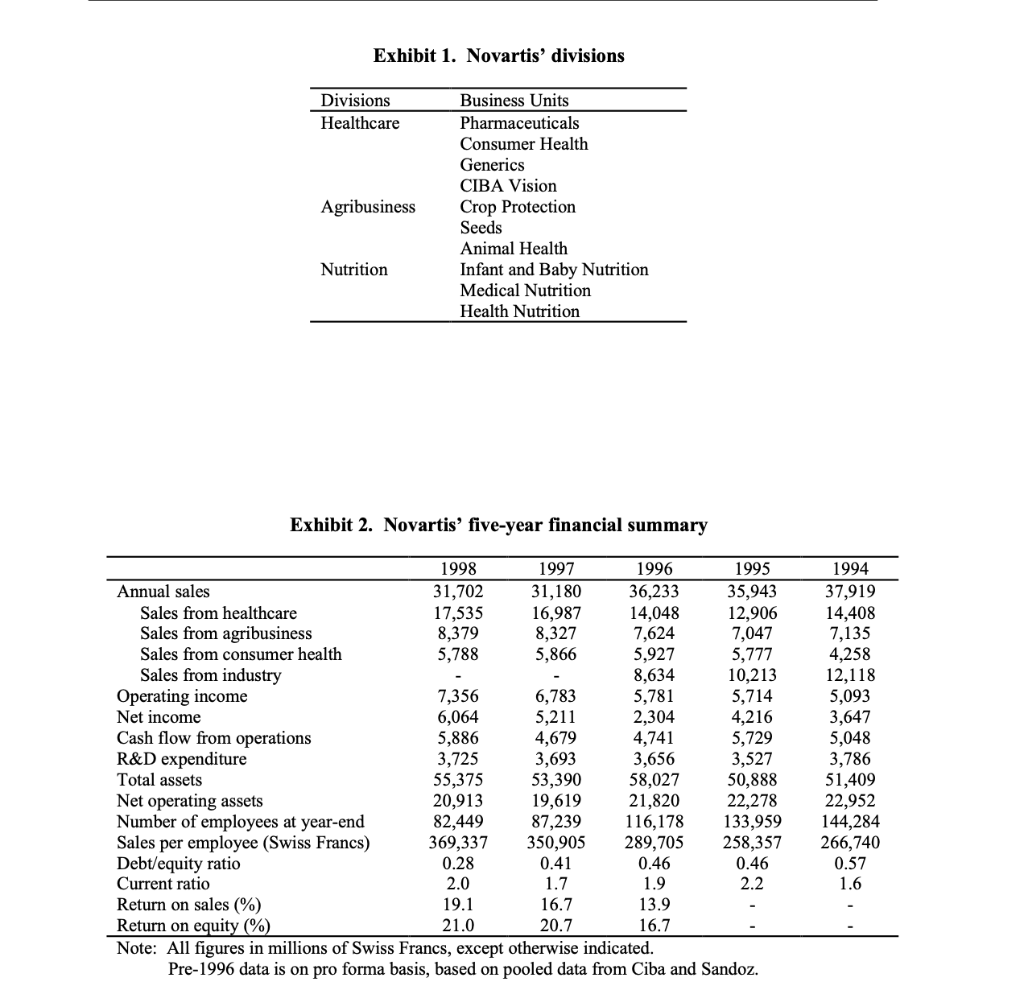

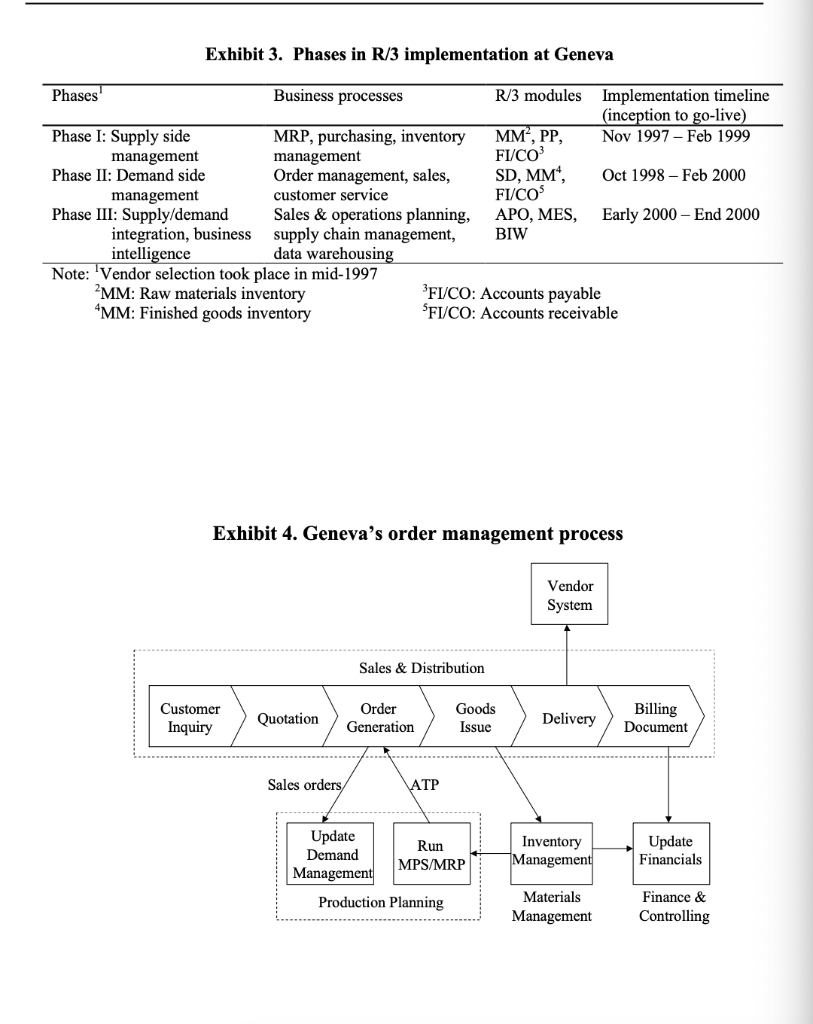

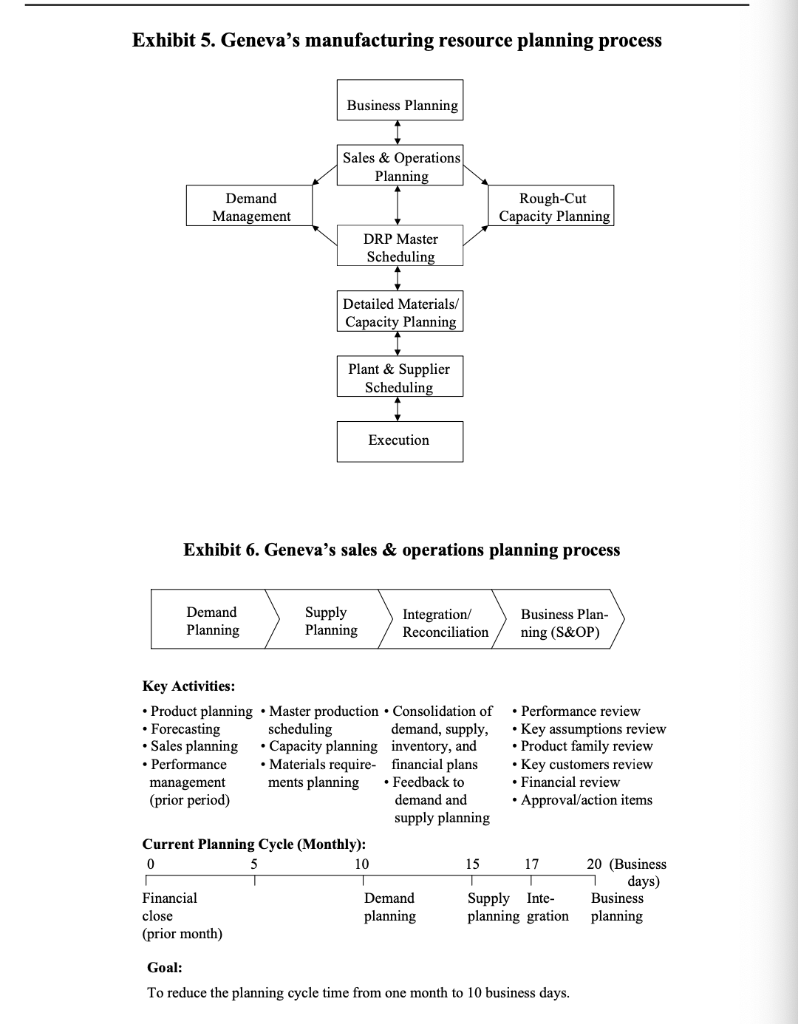

SAP R/3 Implementation at Geneva Pharmaceuticals 1 Company Background Geneva Pharmaceuticals, Inc., one of the world's largest generic drug manufacturers, is the North American hub for the Generics division of Swiss pharmaceutical and life sciences company Novartis International AG. Originally founded by Detroit pharmacist Stanley Tutag in 1946, Geneva moved its headquarters to Broomfield, Colorado in 1974. The company was subsequently acquired by Ciba Corporation in 1979, which in 1996, merged with Sandoz Ltd. in the largest ever healthcare merger to form Novartis. Alex Krauer, Chairman of Novartis and former Chairman and CEO of Ciba, commented on the strengths of the merger: "Strategically, the new company moves into a worldwide leadership position in life sciences. Novartis holds the number two position [globally] in pharmaceuticals, number one in crop protection, and has tremendous development potential in nutrition." The name "Novartis" comes from the Latin term novae artes or new arts, which eloquently captures the company's corporate vision: "to develop new skills in the science of life." Novartis inherited, from its parent companies, a 200 -year heritage of serving consumers in three core business segments: healthcare, agribusiness, and nutrition. Business units organized under these divisions are listed in Exhibit 1. Today, the Basel (Switzerland) based life sciences company employs 82,500 employees worldwide, runs 275 affiliate operations in 142 countries, and generates annual revenues of 32 billion Swiss Francs. Novartis' key financial data for the last five years (1994-98) are presented in Exhibit 2. The company's American Depository Receipts trade on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol NVTSY. Novartis' global leadership in branded pharmaceuticals is complemented by its generic drugs division, Novartis Generics. This division is headquartered in Kundl (Austria), and its U.S. operations are managed by Geneva Pharmaceuticals. In 1998, Geneva had revenues of $300 million, employed nearly 1000 employees, and manufactured over 4.6 billion dosage units of generic drugs. 1 This "freeware" case was written by Dr. Anol Bhattacherjee to serve as a basis for class discussion rather than to demonstrate the effective or ineffective handling of an administrative or business situation. The author is grateful to Randy Weldon, CIO of Geneva Pharmaceuticals, and his coworkers for their unfailing help throughout the course of this project. This case can be downloaded and distributed free of charge for non-profit or academic use, provided the contents are unchanged and this copyright notice is clearly displayed. No part of this case can be used by for-profit organizations without the express written consent of the author. This case also cannot be archived on any web site that requires payment for access. Copyright ( 1999 by Anol Bhattacherjee. All rights reserved. Geneva portfolio currently includes over 200 products in over 500 package sizes, covering a wide range of therapeutic categories, such as nervous system disorders, cardio-vascular therapies, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Its major products include ranitidine, atenolol, diclofenac sodium, ercaf, metoprolol tartrate, triamterene with hydrochlorothiazide, and trifluoperazine. Geneva's business and product information can be obtained from the company web site at www.genevaRx.com. Generic drugs are pharmaceutically and therapeutically equivalent versions of brand name drugs with established safety and efficacy. For instance, acetaminophen is the equivalent of the registered brand name drug Tylenol , aspirin is equivalent of Ecotrin, and ranitidine HCl is equivalent of Zantac. This equivalence is tested and certified within the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), following successful completion of a "bioequivalence study," in which the blood plasma levels of the active generic drug in healthy people are compared with that of the corresponding branded drug. Geneva's business strategy has emphasized growth in two ways: (1) focused growth over a select range of product types, and (2) growth via acquisitions. Internal growth was 14 percent in 1998, primarily due to vigorous growth in the penicillin and cephalosporin businesses. In pursuit of further growth, Geneva spend $52 million in 1997 to upgrade its annual manufacturing capacity to its current capacity of 6 billion units, and another \$23 million in 1998 in clinical trials and new product development. Industry and Competitive Position The generic drug manufacturing industry is fragmented and highly competitive. In 1998, Geneva was the fifth largest player in this industry, up from its eighth rank in 1997 but still below its second rank in 1996. The company's prime competitors fall into three broad categories: (1) generic drugs divisions of major branded drug companies (e.g., Warrick - a division of Schering-Plough and Apothecon - a division of Bristol Myers Squibb), (2) independent generic drug manufacturers (e.g., Mylan, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Barr Laboratories, and Watson Pharmaceuticals), and (3) drug distributors vertically integrating into generics manufacturing (e.g., AndRx). The industry also has about 200 smaller players specializing in the manufacture of niche generic products. While Geneva benefited from the financial strength of Novartis, independent companies typically used public stock markets for funding their growth strategies. In 1998, about 45 percent of prescriptions for medications in the U.S. were filled with generics. The trend toward generics can be attributed to the growth of managed care providers such as health maintenance organizations (HMO), who generally prefer lower cost generic drugs to more expensive brand name alternatives (generic drugs typically cost 30-50 less than equivalent brands). However, no single generics manufacturer has benefited from this trend, because distributors and pharmacies view generic products from different manufacturers as identical substitutes and tend to "autosubstitute" or freely replace generics from one company with those from another based on product availability and pricing at that time. Once substituted, it is very difficult to regain that customer account because pharmacies are disinclined to change product brand, color, and packaging, to avoid confusion among consumers. In addition, consumer trust toward generics has remained lower, following a generic drug scandal in the early 1990's (of which Geneva was not a part). Margins in the generics sector has therefore remained extremely low, and there is a continuous pressure on Geneva and its competitors to reduce costs of operations. Opportunities for international growth are limited because of two reasons. First, consumers in some countries such as Mexico are generally skeptical about the lack of branding because of their cultural background. Second, U.S. generics manufacturers are often undercut by competitors from India and China, where abundance of low-cost labor and less restrictive regulatory requirements (e.g., FDA approval) makes drug manufacturing even less expensive. Continuous price pressures has resulted in a number of recent industry mergers and acquisitions in the generic drugs sector in recent years, as the acquirers seek economies of scale as a means of reducing costs. The search for higher margins has also led some generics companies to venture into the branded drugs sector, providing clinical trials, research and development, and additional manufacturing capacity for branded drugs on an outsourced basis. Major Business Processes Geneva's primary business processes are manufacturing and distribution. The company's manufacturing operations are performed at a 600,000 square foot facility in Broomfield (Colorado), while its two large distribution centers are located in Broomfield and Knoxville (Tennessee). Geneva's manufacturing process is scientific, controlled, and highly precise. A long and rigorous FDA approval process is required prior to commercial production of any drug, whereby the exact formulation of the drug or its "recipe" is documented. Raw materials are sourced from suppliers (sometimes from foreign countries such as China), tested for quality (per FDA requirements), weighed (based on dosage requirements), granulated (i.e., mixed, wetted, dried, milled to specific particle sizes, and blended to assure content uniformity), and compressed into a tablet or poured into a gelatinous capsule. Some products require additional coatings to help in digestion, stabilizing, regulating the release of active ingredients in the human body, or simply to improve taste. Tablets or capsules are then imprinted with the Geneva logo and a product identification number. Following a final inspection, the medications are packaged in childproof bottles with a distinctive Geneva label, or inserted into unit-dose blister packs for shipment. Manufacturing is done in batches, however, the same batch can be split into multiple product types such as tablets and capsules, or tablets of different dosages (e.g., 50mg and 100mg ). Likewise, finished goods from a batch can be packaged in different types of bottles, based on customer needs. These variations add several layers of complexity to the standard manufacturing process and requires tracking of three types of inventory: raw materials, bulk materials, and finished goods, where bulk materials represent the intermediate stage prior to packaging. In some cases, additional intermediates such as coating solution is also tracked. Master production scheduling is focused on the manufacture of bulk materials, based on forecasted demand and replenishment of "safety stocks" at the two distribution centers. Finished goods production depends on the schedule-to-performance, plus availability of packaging materials (bottles and blister packs), which are sourced from outside vendors. Bulk materials and finished goods are warehoused in Broomfield and Knoxville distribution centers (DC) prior to shipping. Since all manufacturing is done was done at Broomfield, inventory replenishment of manufactured products is done first at Broomfield and then at Knoxville. To meet additional customer demand, Geneva also purchases finished goods from smaller manufacturers, who manufacture and package generic drugs under Geneva's level. Since most of these outsourcers are located along the east coast, and hence, they are distributed first to the Knoxville and then to Broomfield. Purchasing is simpler than manufacturing because it requires no bill of materials, no bulk materials management, and no master scheduling; Geneva simply converts planned orders to purchase requisitions, and then to purchase orders, that are invoiced upon delivery. However, the dual role of manufacturing and purchasing is a difficult balancing task, as explained by Joe Camargo, Director of Purchasing and Procurement: "Often times, we are dealing with more than a few decision variables. We have to look at our forecasts, safety stocks, inventory on hand, and generate a replenishment plan. Now we don't want to stock too much of a finished good inventory because that will drive up our inventory holding costs. We tend to be a little more generous on the raw materials side, since they are less costly than finished goods and have longer shop lives. We also have to factor in packaging considerations, since we have a pretty short lead time on packaging materials, and capacity planning, to make sure that we are making efficient use of our available capacity. The entire process is partly automated and partly manual, and often times we are using our own experience and intuition as much as hard data to make a good business decision." Geneva supplies to a total of about 250 customers, including distributors (e.g., McKesson, Cardinal, Bergen), drugstore chains (e.g., Walgreen, Rite-Aid), grocery chains with in-store pharmacies (e.g., Safeway, Kroger), mail order pharmacies (e.g., Medco, Walgreen), HMOs (e.g., Pacificare, Cigna), hospitals (e.g., Columbia, St. Luke's), independent retail pharmacies, and governmental agencies (e.g., U.S. Army, Veterans Administration, Federal prisons). About 70 percent of Geneva's sales goes to distributors, another 20 percent goes to drugstore chains, while HMOs, government, retail pharmacies, and others account for the remaining 10 percent. Distributors purchase generic drugs wholesale from Geneva, and then resell them to retail and mail order pharmacies, who are sometimes direct customers of Geneva. The volume and dollar amount of transaction vary greatly from one customer to another, and while distributors are sometimes allow Geneva some lead time to fulfill in a large order, retail pharmacies typically are unwilling to make that concession. One emerging potential customer segment is Internet-based drug retailers such as Drugstore.com and PlanetRx.com. These online drugstores do not maintain any inventory of their own, but instead accept customer orders and pass on those orders to any wholesaler or manufacturer that can fill those orders in short notice. These small, customized, and unpredictable orders do not fit well with Geneva's wholesale, high-volume production strategy, and hence, the company has decided against direct retailing to consumers via mail order or the Internet, at least for the near future. As is standard in the generics industry, Geneva uses a complex incentive system consisting of "rebates" and "chargebacks" to entice distributors and pharmacies to buy its products. Each drug is assigned a "published industry price" by industry associations, but Geneva rebates that price to distributors on their sales contracts. For instance, if the published price is $10, and the rebates assigned to a distributor is $3, then the contract price on that drug is $7. Rebate amounts are determined by the sales management based on negotiations with customers. Often times, customers get proposals to buy the product cheaper from a different manufacturer and ask Geneva for a corresponding discount. Depending on how badly Geneva wants that particular customer or push that product, it may offer a rebate or increase an existing rebate. Rebates can vary from one product to another (for the same customer) and/or from one order volume to another (for the same product). Likewise, pharmacies ordering Geneva's products are paid back a fraction of the sales proceeds as chargebacks. The majority of Geneva's orders come through EDI. These orders are passed though multiple filters in an automated order processing system to check if the customer has an active customer number and sufficient credit, if the item ordered is correct and available in inventory. Customers are then assigned to either the Broomfield or Knoxville DC based on quantity ordered, delivery expiration dates, and whether the customer would accept split lots. If the quantity ordered is not available at the primary DC (say, Knoxville), a second allocation is made to the secondary DC (Broomfield, in this case). If the order cannot be filled immediately, a backorder will be generated and the Broomfield manufacturing unit informed of the same. Once filled, the distribution unit will print the order and ship it to the customer, and send order information to accounts receivable for invoicing. The overall effectiveness of the fulfillment process is measured by two customer service metrics: (1) the ratio between the number of lines on the order that can be filled immediately (partial fills allowed) to the total number of lines ordered by the customer (called "firstfill"), and (2) the percentage of items send from the primary DC. Fill patterns are important because customers typically prefer to get all items ordered in one shipment. Matching customer demand to production schedules is often difficult because of speculative buying on the part of customers. Prices of drugs are typically reassessed at the start of every fiscal year, and a distributor may place a very large order at the end of the previous year to escape a potential price increase at the start of the next year (these products would then be stockpiled for reselling at higher prices next year). Likewise, a distributor may place a large order at the end of its financial year to transfer cash-on-hand to cost-of-goods-sold, for tax purposes or to ward off a potential acquisition threat. Unfortunately, most generics companies do not have the built-in capacity to deliver such orders within short time frames, yet inability to fulfill orders may lead to the loss of an important customer. Safety stocks help meet some of these unforeseen demands, however maintaining such inventory consumes operating resources and reduce margins further. SAP R/3 Implementation Up until 1996, Geneva's information systems (IS) consisted of a wide array of software programs for running procurement, manufacturing, accounting, sales, and other mission-critical processes. The primary hardware platform was IBM AS/400, running multiple operational databases (mostly DB/2 ) and connected to desktop microcomputers via a token-ring local area network (LAN). Each business unit had deployed applications in an ad hoc manner to meet its immediate needs, which were incompatible across business units. For instance, the manufacturing unit (e.g., materials requirements planning) utilized a manufacturing application called MacPac, financial accounting used Software/2000, and planning/budgeting used FYI-Planner. These systems were not interoperable, and data that were shared across systems (e.g., accounts receivable data was used by order management and financial accounting packages, customer demand was used in both sales and manufacturing systems) had to be double-booked and rekeyed manually. This led to higher incidence of data entry errors, higher costs of error processing, and greater data inconsistency. Further, data was locked within "functional silos" and were unable to support processes that cut across multiple business units (e.g., end-to-end supply chain management). It was apparent that a common, integrated company-wide solution would not only improve data consistency and accuracy, but also reduce system maintenance costs (e.g., data reentry and error correction) and enable implementation of new value-added processes across business units. In view of these limitations, in 1996, corporate management at Geneva initiated a search for technology solutions that could streamline its internal processes, lower costs of operations, and strategically position the company to take advantage of new value-added processes. More specifically, it wanted an enterprise resource planning (ERP) software that could: (1) implement best practices in business processes, (2) provide operational efficiency by integrating data across business units, (3) reduce errors due to incorrect keying or rekeying of data, (4) reduce system maintenance costs by standardizing business data, (5) be flexible enough to integrate with new systems (as more companies are acquired), (6) support growth in product and customer categories, and (7) is Y2K (year 2000) compliant. The worldwide divisions of Novartis were considering two ERP packages at that time: BPCS from Software Systems Associates and R/3 system from SAP. Eventually, branded drug divisions decided to standardize their data processing environment using BPCS, and generics agreed on deploying R/3. 2 A brief description of the R/3 software is provided in the appendix. R/3 implementation at Geneva was planned in three phases (see Exhibit 3). Phase I focused on the supply side processes (e.g., manufacturing requirements planning, procurement planning), Phase II was concerned with demand side processes (e.g., order management, customer service), and the final phase was aimed at integrating supply side and demand side processes (e.g., supply chain management). Randy Weldon, Geneva's Chief Information Officer, outlined the goals of each phase as: "In Phase I, we were trying to get better performance-to-master production schedule and maybe reduce our cost of operations. Our Phase II goals are to improve sales and operations planning, and as a result, reduce back orders and improve customer service. In Phase III, we hope to provide end-to-end supply chain integration, so that we can dynamically alter our production schedules to fluctuating demands from our customers." For each phase, specific R/3 modules were identified for implementation. These modules along with implementation timelines are listed in Exhibit 3. The three phases are described in detail next. 2 However, each generics subsidiary had its own SAP R/3 implementation, and therefore data sharing across these divisions remained problematic. Phase I: Supply Side Processes The first phase of R/3 implementation started on November 1, 1997 with the goal of migrating all supply-side processes, such as purchasing management, capacity planning, master scheduling, inventory management, quality control, and accounts payable from diverse hardware/software platforms to a unified R/3 environment. These supply processes were previously very manual and labor intensive. A Macpac package running on an IBM AS/400 machine was used to control shop floor operations, prepare master schedules, and perform maintenance management. However, the system did not have simulation capability to run alternate production plans against the master schedule, and was therefore not used for estimation. The system also did not support a formal process for distribution resource planning (DRP), instead generated a simple replenishment schedule based on predefined economic order quantities. Materials requirements planning (MRP) was only partially supported in that the system generated production requirements and master schedule but did not support planned orders (e.g., generating planned orders, checking items in planned orders against the inventory or production plan, converting planned orders to purchase orders or manufacturing orders). Consequently, entering planned orders, checking for errors, and performing order conversion were all entered manually, item by item, by different sales personnel (which left room for rekeying error). Macpac did have a capacity resource planning (CRP) functionality, but this feature was not used since it required heavy custom programming and major enhancements to master data. The system had already been so heavily customized over the years, that even a routine system upgrade was considered too unwieldy and expensive. Most importantly, the existing system did not position Geneva well for the future, since it failed to accommodate consigned inventory, vendor-managed inventory, paperless purchasing, and other innovations in purchasing and procurement that Geneva wanted to implement. The objectives of Phase I were therefore to migrate existing processes from Macpac to R/3, automate supply side process not supported by MacPac, and integrate all supply-side data in a single, real-time database so that the synergies could be exploited across manufacturing and purchasing processes. System integration was also expected to reduce inventory and production costs, improve performance-to-master scheduling, and help managers make more optimal manufacturing and purchase decisions. Since R/3 would force all data to be entered only once (at source by the appropriate shop floor personnel), the need of data reentry would be eliminated, and hence costs of data reconciliation would be reduced. The processes to be migrated from MacPac (e.g., MRP, procurement) were fairly standardized and efficient, and were hence not targeted for redesign or enhancement. Three SAP modules were scheduled for deployment: materials management (MM), production planning (PP), and accounts payable component of financial accounting (FI). Exhibit A-1 in Appendix provides brief descriptions of these and other commonly referenced R/3 modules. Phase I of R/3 implementation employed about ten IS personnel, ten full-time users, and ten part-time users from business units within Geneva. Whitman-Hart, a consulting company with prior experience in R/3 implementation, was contracted to assist with the migration effort. These external consultants consisted of one R/3 basis person (for implementing the technical core of the R/3 engine), three R/3 configurators (for mapping R/3 configuration tables in MM, PP, and FI modules to Geneva's needs), and two ABAP programmers (for custom coding unique requirements not supported by SAP). These consultants brought in valuable implementation experience, which was absolutely vital, given that Geneva had no in-house expertise in R/3 at that time. Verne Evans, Director of Supply Chain Management and a "super user" of MacPac, was assigned the project manager for this phase. SAP's rapid implementation methodology called Accelerated SAP (ASAP) was selected for deployment, because it promised a short implementation cycle of only six months. 3 Four months later, Geneva found that little progress had been made in the implementation process despite substantial investments on hardware, software, and consultants. System requirements were not defined correctly or in adequate detail, there was little communication or coordination of activities among consultants, IS personnel, and user groups, and the project manager was unable to identify or resolve problems because he had no prior R/3 experience. In the words of a senior manager, "The implementation was clearly spinning out of control." Consultants employed by Whitman-Hart were technical specialists, and had little knowledge of the business domain. The ASAP methodology seemed to be failing, because although it allowed a quick canned implementation, it was not flexible enough to meet Geneva's extensive customization needs, did not support process improvements, and alienated functional user groups from system implementation. To get the project back into track and give it leadership and direction, in February 1998, Geneva hired Randy Weldon as its new CIO. Weldon brought in valuable project management experience in R/3 from his previous employer, StorageTek. 4 From his prior R/3 experience, Weldon knew that ERP was fundamentally about people and process change, rather than about installing and configuring systems, and that successful implementation would require the commitment and collaboration of all three stakeholder groups: functional users, IS staff, and consultants. He instituted a new project management team, consisting of one IS manager, one functional manager, and one senior R/3 consultant. Because Geneva's internal IS department had no R/3 implementation experience, a new team of R/3 professionals (including R/3 basis personnel and Oracle database administrators) was recruited. Anna Bourgeois, with over three years of R/3 experience at Compaq Computers, was brought in to lead Geneva's internal IS team. Weldon was not particularly in favor of Whitman-Hart or the ASAP methodology. However, for project expediency, he decided to continue with Whitman-Hart and ASAP for Phase 1, and explore other options for subsequent phases. By February 1999, the raw materials and manufacturing component of R/3's MM module was "up and running." But this module was not yet integrated with distribution (Phase II) and therefore did not have the capability to readjust production runs based on current sales data. However, several business metrics such as yield losses and key performance indicators showed performance improvement following R/3 implementation. For instance, the number of planning activities performed by a single individual was doubled. Job roles were streamlined, standardized, and consolidated, so that the same person could perform more "value-added" activities. Since R/3 eliminated the need for data rekeying and validating, the portion of the inventory control unit that dealt with data entry and error checking was disbanded and these employees were taught new skills for reassignment to other purchasing and procurement processes. But R/3 also had its share of disappointments, as explained by Camargo: 3 ASAP is SAP's rapid implementation methodology that provides implementers a detailed roadmap of the implementation life cycle, grouped into five phases: project preparation, business blueprint, realization, final preparation, and go live. ASAP provides a detailed listing of activities to be performed in each phase, checklists, predefined templates (e.g., business processes, cutover plans), project management tools, questionnaires (e.g., to define business process requirements), and a Question \& Answer Database 4 StorageTek is a leading manufacturer of magnetic tape and disk components also based in Colorado. "Ironically, one of the problems we have with SAP, that we did not have with Macpac, is for the job to carry the original due date and the current due date, and measure production completion against the original due date. SAP only allows us to capture one due date, and if we change the date to reflect our current due date, that throws our entire planning process into disarray. To measure how we are filling orders, we have to do that manually, offline, on a spreadsheet. And we can't record that data either in SAP to measure performance improvements over time." Bourgeois summed up the implementation process as: "Phase I, in my opinion, was not done in the most effective way. It was done as quickly as possible, but we did not modify the software, did not change the process, or did not write any custom report. Looking back, we should have done things differently. But we had some problems with the consultants, and by the time I came in, it was a little too late to really make a change. But we learned from these mistakes, and we hope to do a better job with Phases II and III." Phase II: Demand Side Processes Beginning around October 1998, the goals of the second phase were to redesign demand-side processes such as marketing, order fulfillment, customer sales and service, and accounts receivable, and then implement the reengineered processes using R/3. Geneva was undergoing major business transformations especially in the areas of customer sales and service, and previous systems (Macpac, FYI Planner, etc.) were unable to accommodate these changes. For instance, in 1998, Geneva started a customer-based forecasting process for key customer accounts. It was expected that a better prediction of order patterns from major customers would help the company improve its master scheduling, while reducing safety stock and missed orders. The prior forecasting software, FYI Planner, did not allow forecasting on a customer-by-customer basis. Besides, demand-side processes suffered from similar lack of data integration and real-time access as supply side processes, and R/3 implementation, by virtue of its real-time integration of all operational data would help manage crossfunctional processes better. Mark Mecca, Director of Customer Partnering, observed: "Before SAP, much of our customer sales and service were managed in batch mode using MacPac. EDI orders came in once a night, chargebacks came in once a day, invoicing is done overnight, shipments got posted once a day; so you don't know what you shipped for the day until that data was entered the following day. SAP will allow us to have access to real-time data across the enterprise. There will be complete integration with accounting, so we will get accurate accounts receivable data at the time a customer initiates a sales transaction. Sometime in the future, hopefully, we will have enough integration with our manufacturing processes so that we can look at our manufacturing schedule and promise a customer exactly when we can fill his order." However, the second phase was much more challenging than the first phase, given the non-standard percentages varied across customers, customer-product combinations, and customer-product-order volume combinations. Additionally, the same customer sometimes had multiple accounts with Geneva and had a different rebate percentage negotiated for each account. Bourgeois was assigned overall responsibility of the project, by virtue of her extensive knowledge of EDI, R/3 interface conversion, and sales and distribution processes, and ability to serve as a technical liaison between application and basis personnel. Whitman-Hart was replaced with a new consulting firm, Arthur Andersen Business Consulting, to assist Geneva with the second and third phases of R/3 implementation. Oliver White, a consulting firm specializing in operational processes for manufacturing firms, was also hired to help redesign existing sales and distribution processes using "best practices," prior to R/3 implementation. Weldon explained the reason for hiring two consulting groups: "Arthur Anderson was very knowledgeable in the technical and configurational aspects of SAP implementation, but Oliver White was the process guru. Unlike Phase I, we were clearly targeting process redesign and enhancement in Phases II and III, and Oliver White brought in 'best practices' by virtue of their extensive experience with process changes in manufacturing organizations. Since Phase I was somewhat of a disaster, we wanted to make sure that we did everything right in Phases II and III and not skimp on resources." Technical implementation in Phase II proceeded in three stages: conceptual design, conference room pilot, and change management. In the conceptual design stage, key users most knowledgeable with the existing process were identified, assembled in a room, and interviewed, with assistance from Oliver White consultants. Process diagrams were constructed on "post-it" notes and stuck to the walls of a conference room for others to view, critique, and suggest modifications. The scope and boundaries of existing processes, inputs and deliverables of each process, system interfaces, extent of process customization, and required level of system flexibility were analyzed. An iterative process was employed to identify and eliminate activities that did not add value, and generate alternative process flows. The goal was to map the baseline or existing ("AS-IS") processes, identify bottlenecks and problem areas, and thereby, to create reengineered ("TO-BE") processes. This information became the basis for subsequent configuration of the R/3 system in the conference room pilot stage. A core team of 20 IS personnel, users, and consultants worked full-time on conceptual design for 2.5 months (this team later expanded to 35 members in the conference room pilot stage). Another 30 users were involved part-time in this effort; these individuals were brought in for focused periods of time (between 4 and 14 hours) to discuss, clarify, and agree on complex distribution-related issues. The core team was divided into five groups to examine different aspects of the distribution process: (1) product and business planning, (2) preorder (pricing, chargebacks, rebates, contracts, etc.), (3) order processing, (4) fulfillment (shipping, delivery confirmation, etc.), and (5) post-order (accounts receivable, credit management, customer service, etc.). Thirteen different improvement areas were identified, of which four key areas emerged repeatedly from cross-functional analysis by the five groups and were targeted for improvement: product destruction, customer dispute resolution, pricing strategy, and service level. Elaborate models were constructed (via fish bone approach) for each of these four areas to identify what factors drove these areas, what was the source of problems in these areas, and how could they be improved using policy initiatives. The conceptual design results were used to configure and test prototype R/3 systems for each of the four key improvement areas in the conference room pilot stage. The purpose of the prototypes was to test and refine different aspects of the redesigned processes such as forecast planning, contract pricing, chargeback strategy determination, receivables creation, pre-transaction credit checking, basic reporting, and so forth in a simulated environment. The prototypes were modified several times based on user feedback, and the final versions were targeted for rollout using the ASAP methodology. In the change management stage, five training rooms were equipped with computers running the client version of the R/3 software to train users on the redesigned processes and the new R/3 environment. An advisory committee was formed to oversee and coordinate the change management process. Reporting directly to the senior vice president level, this committee was given the mandate and resources to plan and implement any change strategies that they would consider beneficial. A change management professional and several trainers were brought in to assist with this effort. Multiple "brown bag luncheons" were organized to plan out the course of change and discuss what change strategies would be least disruptive. Super users and functional managers, who had the organizational position to influence the behaviors of colleagues or subordinates in their respective units, were identified and targeted as potential change agents. The idea was to seed individual business units with change agents they could trust and relate to, in an effort to drive a grassroots program for change. To stimulate employee awareness, prior to actual training, signs were put up throughout the company that said, "Do you know that your job is changing?" Company newsletters were used to enhance project visibility and to address employee questions or concerns about the impending change. A separate telephone line was created for employees to call anytime and inquire about the project and how their jobs would be affected. The human resources unit conducted an employee survey to understand how employees viewed the R/3 implementation and gauge their receptivity to changes in job roles as a result of this implementation. Training proceeded full-time for three weeks. Each user received an average of 3-5 days of training on process and system aspects. Training was hands-on, team-oriented, and continuously mentored, and was oriented around employees' job roles such as how to process customer orders, how to move inventory around, and how to make general ledger entries, rather than how to use the R/3 system. Weldon described the rationale for this unique, non-traditional mode of training: "Traditional system training does not work very well for SAP implementation because this is not only a technology change but also a change in work process, culture, and habits, and these are very difficult things to change. You are talking about changing attitudes and job roles that have been ingrained in employees' minds for years and in some cases, decades. System training will overwhelm less sophisticated users and they will think, 'O my God, I have no clue what this computer thing is all about, I don't know what to do if the screen freezes, I don't know how to handle exceptions, I'm sure to fail.' Training should not focus on how they should use the system, but on how they should do their own job using the system. In our case, it was a regular on-the-job training rather than a system training, and employees approached it as something that would help them do their job better." Several startling revelations were uncovered during the training process. First, there was a considerable degree of confusion among employees on what their exact job responsibilities were, even in the pre-R/3 era. Some training resources had to be expended in reconciling these differences, and to eliminate ambiguity about their post-implementation roles. Second, Geneva's departments were very much functionally oriented and wanted the highest level of efficiency from their department, sometimes to the detriment of other departments or the overall process. This has been a sticky cultural problem, and at the time of the case, the advisory committee was working with senior management to see if any structural changes could be initiated within the company to affect a mindset change. Third, Geneva realized that change must also be initiated on the customer side, so that customers are aware of the system's benefits and are able to use it appropriately. In the interest of project completion, customer education programs were postponed until the completion of Phase III of R/3 implementation. The primary business metric tracked for Phase II implementation was customer service level, while other metrics included days of inventory on hand, dollar amount in disputes, dollar amount destroyed, and so forth. Customer service was assessed by Geneva's customers as: (1) whether the item ordered was in stock, (2) whether Geneva was able to fill the entire order in one shipment, and (3) if backordered, whether the backorder delivered on time. With a customer service levels in the 80's, Geneva has lagged its industry competitors (mostly in the mid 90's), but has set an aggressive goal to exceed 99.5 percent service level by year-end 1999. Camargo observed that there was some decrease in customer service, but this decrease was not due to R/3 implementation but because Geneva faced an impending capacity shortfall and the planners did not foresee the shortfall quickly enough to implement contingency plans. Camargo expected that such problems would be alleviated as performance-to-schedule and demand forecasting improved as a result of R/3 implementation. Given that Phase II implementation is still underway at the time of the case ("go live" date is February 1, 2000), it is still too early to assess whether these targets are reached. Phase 3: Integrating Supply and Demand Geneva's quest for integrating supply and demand side processes began in 1994 with its supply chain management (SCM) initiative. But the program was shelved for several years due to the nonintegrated nature of systems, immaturity of the discipline, and financial limitations. The initiative resurfaced on the planning boards in 1998 under the leadership of Verne Evans, Director of SCM, as R/3 promised to remove the technological bottlenecks that prevented successful SCM implementation. Though SCM theoretically extends beyond the company's boundaries to include its suppliers and customers, Geneva targeted the mission-critical the manufacturing resource planning (MRP-II) component within SCM, and more specifically, the Sales and Operations Planning (SOP) process as the means of implementing "just-in-time" production scheduling. SOP dynamically linked planning activities in Geneva's upstream (manufacturing) and downstream (sales) operations, allowing the company to continuously update its manufacturing capacity and scheduling in response to continuously changing customer demands (both planned and unanticipated). Geneva's MRP-II and SOP processes are illustrated in Exhibits 5 and 6 respectively. Until the mid-1990's, Geneva had no formal SOP process, either manual or automated. Manufacturing planning was isolated from demand data, and was primarily based on historical demand patterns. If a customer (distributor) placed an unexpected order or requested a change in an existing order, the manufacturing unit was unable to adjust their production plan accordingly. This lack of flexibility led to unfilled orders or excess inventory and dissatisfied (and sometimes lost) customers. Prior sales and manufacturing systems were incompatible with each other, and did not allow the integration of supply and demand data, as required by SOP. In case production plans required modification to accommodate a request from a major customer, such decisions were made on an ad-hoc basis, based on intuition rather than business rationale, which sometimes had adverse repercussions on manufacturing operations. To remedy these problems, Geneva started a manual SOP process in 1997 (see Exhibit 6). In this approach, after the financial close of each month, sales planning and forecast data were aggregated from order entry and forecasting systems, validated, and manually keyed into master scheduling and production planning systems. Likewise, prior period production and inventory data were entered into order management systems. The supply planning team and demand analysis team arrived at their own independent analysis of what target production and target sales should be. These estimates (likely to be different) were subsequently reviewed in a joint meeting of demand analysts and master schedulers and reconciliated. Once an agreement was reached, senior executives (President of Geneva and Senior Vice Presidents), convened a business planning meeting, where the final production plan and demand schedule were analyzed based on business assumptions, key customers, key performance indicators, financial goals and projections (market share, revenues, profits), and other strategic initiatives (e.g., introduction of a new product). The purpose of this final meeting was not only to fine-tune the master schedule, but also to reexamine the corporate assumptions, growth estimates, and the like in light of the master schedule, and to develop a better understanding of the corporate business. The entire planning process took 20 business days (one month), of which the first 10 days were spent in data reentry and validation across corporate systems, followed by five days of demand planning, two days of supply planning, and three days of reconciliation. The final business planning meeting was scheduled on the last Friday of the month to approve production plans for the following month. Interestingly, when the planning process was completed one month later, the planning team had a good idea of the production schedule one month prior. If Geneva decided to override the targeted production plans to accommodate a customer request, such changes undermined the utility of the SOP process. While the redesigned SOP process was a major improvement over the pre-SOP era, the manual process was itself limited by the time-lag and errors in data reentry and validation across sales, production, and financial systems. Further, the process took one month, and was not sensitive to changes in customer orders placed less than a month from their requested delivery dates. Since much of the planning time was consumed in reentering and validating data from one system to another, Evans estimated that if an automated system supported real-time integration of all supply and demand data in a single unified database, the planning cycle could be reduced to ten business days. Though SAP provided a SOP module with their R/3 package, Geneva's R/3 project management team believed that this module lacked the "intelligence" required to generate an "optimal" production plan from continuously changing supply and demand data, even when all data were available in a common database. The R/3 system was originally designed as a data repository, not an analysis tool to solve complex supply chain problems or provide simulation capabilities 5. Subsequently, in 1999 , when SAP added a new Advanced Purchase Optimizer (APO) module to help with data analysis, Geneva realized that the combination of R/3's SOP and APO modules would be the answer to their unique SOP needs. At the time of the case, Geneva was in the initial requirements definition stage of SOP implementation. To aid in this effort, Oliver White had created a template that could aggregate all relevant data required for SOP from distribution, operations, purchasing, quality control, and other functional databases, and tie these data to their source processes. It was expected that the template would provide a common reference point for all individuals participating in the SOP process and synchronize their decision processes. The primary business metric targeted for improvement in Phase III implementation is "available to promise" (ATP), i.e., whether Geneva is able to fulfill a customer order by the promised time. ATP is an integration of customer service level and business performance, the erstwhile key business metrics in the pre-SOP era. Customers often placed orders too large to be fulfilled immediately, and ATP was expected to provide customers with reasonably accurate dates on when they should expect which part of their order to be filled. Generating and meeting these dates would enable Geneva improve its customer service levels that not providing any fulfillment dates at all. With declining profit margins, as the generics industry is forced to explore new means of cost reduction, Geneva expects that thin inventories, just-in-time manufacturing, and top quality customer service will eventually be the drivers of success, hence the importance of this metric. Evans explains the importance of ATP as a business metric as: "Most of our customers understand the dynamics of our business, and how difficult it is for us to fulfill a large order instantaneously with limited production capacity. But most of them are willing to bear with backorders if we can promise them a reasonable delivery date for their backorder and actually deliver on that date. That way, we take less of a customer service level hit than defaulting on the order or being unable to accommodate it. In commodity business such as ours, customer service is the king. Our customers may be willing to pay a little premium over the market for assured and reliable service, so that they can meet their obligations to their customers. Customer service may be a strategic way to build long-term relationships with our customers, but of course, we are far from proving or disproving that hypothesis." Future Plans Despite some initial setbacks in Phase I, Geneva is now back on the road to a successful R/3 implementation. The senior management, functional units, and IS personnel are all enthusiastic about the project and looking forward to its deployment in all operational areas of business and beyond. R/3 implementation has opened up new possibilities to Geneva and more means of competing in the 5 Typically, manufacturing companies requiring SCM analysis used additional analysis tools from I2 Technologies or Manugistics on top of ERP databases from SAP or Oracle for SCM purposes. intensely competitive generic drugs industry. Weldon provided an overall assessment of the benefits achieved via R/3 implementation: "In my opinion, we are doing most of the same things, but we are doing them better, faster, and with fewer resources. We are able to better integrate our operational data, and are able to access that data in a timely manner for making critical business decisions. At the same time, SAP implementation has placed us in a position to leverage future technological improvements and process innovations, and we expect to grow with the system over time." Currently, the primary focus of Geneva's R/3 implementation is timely completion of Phase II and III by February 2000 and December 2000 respectively. Once completed, the implementation team can then turn to some of R/3's additional capabilities that are not being utilized at Geneva. In particular, the quality control and human resource modules are earmarked for implementation after Phase III. Additionally, Geneva plans to strengthen relationships with key suppliers and customers by seamlessly integrating the entire supply chain. The first step in this direction is vendor managed inventory (VMI), that was initiated by Geneva in April 1998 for a grocery store chain and a major distributor. In this arrangement, Geneva obtains real-time, updated, electronic information about customers' inventories, and replenish their inventories on a just-in-time basis without a formal ordering process, based on their demand patterns, sales forecast, and actual sales (effectively operating as customers' purchasing unit). 6 Geneva's current VMI system, Score, was purchased from Supply Chain Solutions (SCS) in 1998. Though Mecca is satisfied with this system, he believes that Geneva can benefit more from R/3's ATP module via a combination of VMI functionality and seamless company-wide data integration. Currently, some of Geneva's customers are hesitant to adopt VMI because sharing of critical sales data may cause them to lose bargaining power vis--vis their suppliers or prevent them from speculative buying. But over the long-term, the inherent business need for cost reduction in the generics industry is expected to drive these and other customers toward VMI. Geneva wants to ensure that the company is ready if and when such opportunity arises. 6 Real-time customer forecast and sales data is run through a VMI software (a mini-MRP system), which determines optimum safety stock levels and reorder points for customers, and a corresponding, more optimum production schedule for Geneva. Initial performance statistics at the grocery store chain indicated that customer service levels increased from 96 percent to 99.5 percent and on-hand inventory decreased from 8 weeks to six weeks as a result of VMI implementation. For the distributor, Geneva expects that VMI will reduce on-hand inventory from seven months to three months. Exhibit 1. Novartis' divisions Exhibit 2. Novartis' five-year financial summary Note: All figures in millions of Swiss Francs, except otherwise indicated. Pre-1996 data is on pro forma basis, based on pooled data from Ciba and Sandoz. Exhibit 3. Phases in R/3 implementation at Geneva Exhibit 4. Geneva's order management process Exhibit 5. Geneva's manufacturing resource planning process Exhibit 6. Geneva's sales \& operations planning process Key Activities: - Product planning - Master production - Consolidation of - Performance review - Forecasting scheduling demand, supply, Key assumptions review - Sales planning - Capacity planning inventory, and Product family review - Performance Materials require- financial plans - Key customers review management ments planning - Feedback to Financial review (prior period) demand and Approval/action items supply planning Goal: To reduce the planning cycle time from one month to 10 business days

Step by Step Solution

There are 3 Steps involved in it

Get step-by-step solutions from verified subject matter experts