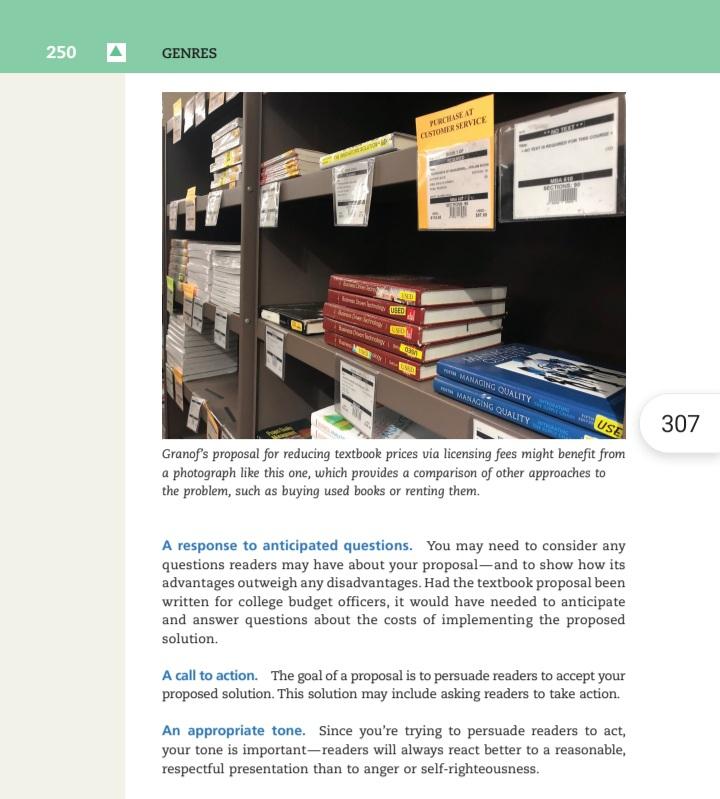

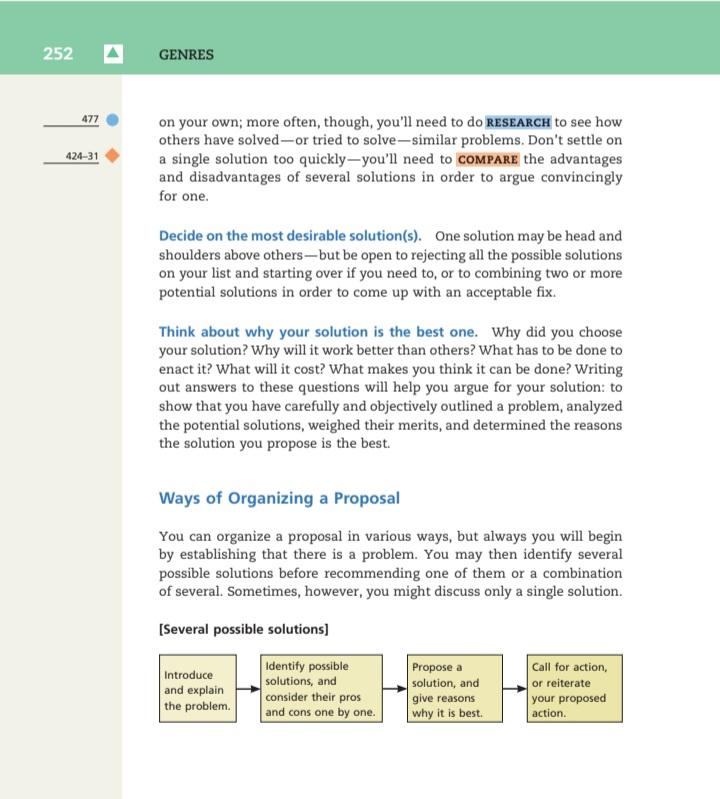

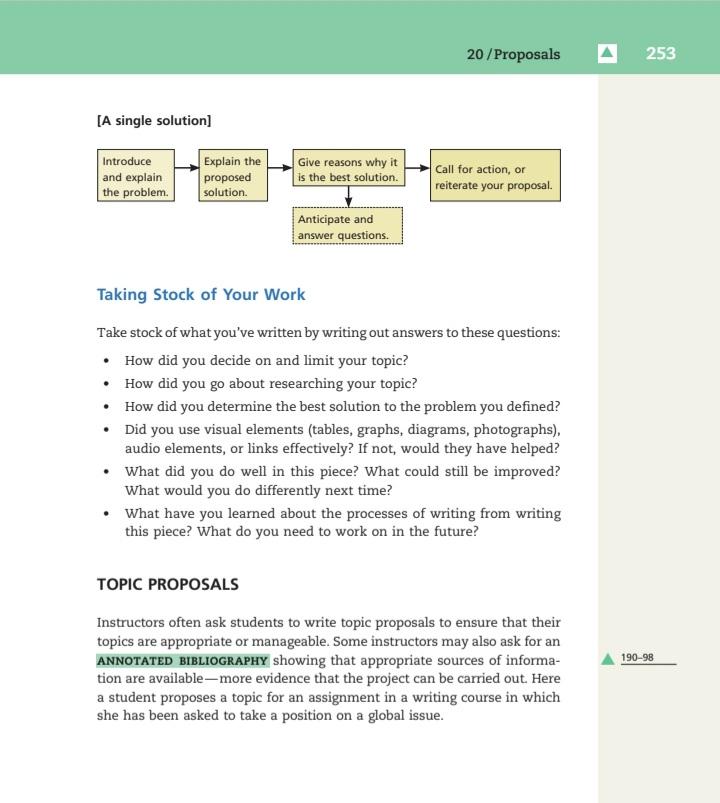

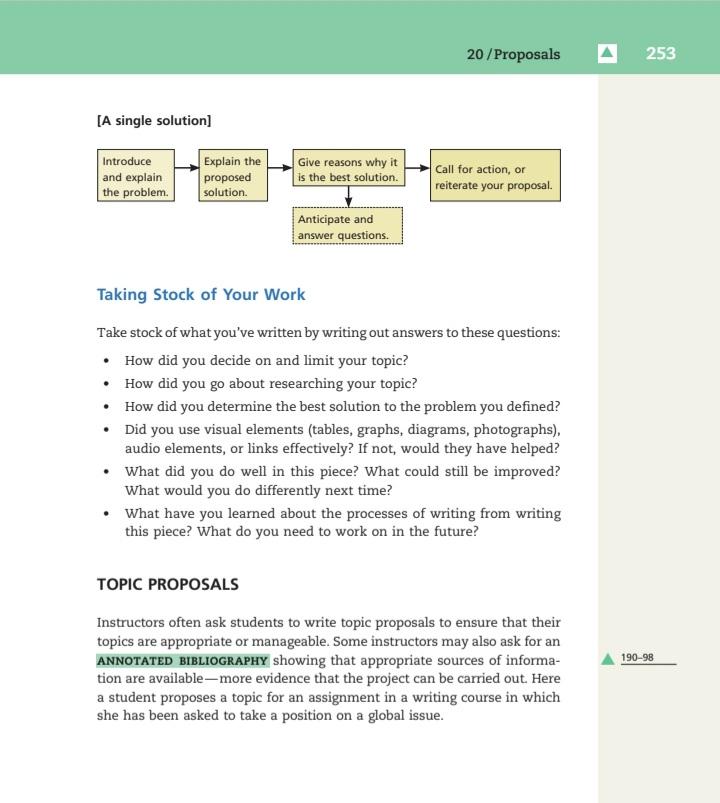

20 Proposals Proposals are part of our personal lives: lovers propose marriage, friends propose sharing dinner and a movie, you offer to pay half the cost of a car and insurance if your parents will pay the other half. They are also part of our academic and professional lives: student leaders lobby for lights on bike paths. Musicians, artists, writers, and educators apply for grants. Researchers in all fields of the humanities, social sciences, sciences, and technology seek funding for their projects. In business, contractors bid on building projects, and companies and freelancers solicit work from potential clients. These are all examples of proposals, ideas put forward for consideration that say, "Here is a solution to a problem" or "This is what ought to be done." For example, here is a proposal for reducing the costs of college textbooks, written by an accounting professor at the University of Texas who is chairman of the university's Co-op Bookstore and himself a textbook author, 303 MICHAEL GRANOF Course Requirement: Extortion By now, entering college students and their parents have been warned: textbooks are outrageously expensive. Few textbooks for semester-long courses retail for less than $120, and those for science and math courses typically approach $180. Contrast this with the $20 to $30 cost of most hardcover best sellers and other trade books. Perhaps these students and their parents can take comfort in knowing that the federal government empathizes with them, and in an attempt to ease their pain Congress asked its Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance to suggest a cure for the problem. 246 20/Proposals 247 304 Unfortunately, though, the committee has proposed a remedy that would only worsen the problem. The committee's report, released in May, mainly proposes strength- ening the market for used textbooks-by encouraging college book- stores to guarantee that they will buy back textbooks, establishing online book swaps among students, and urging faculty to avoid switch- ing textbooks from one semester to the next. The fatal flaw in that proposal (and similar ones made by many state legislatures) is that used books are the cause of, not the cure for, high textbook prices. Yet there is a way to lighten the load for students in their budgets, if not their backpacks. With small modifications to the institutional arrangements between universities, publishers, and students, textbook costs could be reduced-and these changes could be made without government intervention. Today the used-book market is exceedingly well organized and 5 efficient. Campus bookstores buy back not only the books that will be used at their university the next semester but also those that will not Those that are no longer on their lists of required books they resell to national wholesalers, which in turn sell them to college bookstores on campuses where they will be required. This means that even if a text is being adopted for the first time at a particular college, there is almost certain to be an ample supply of used copies. As a result, publishers have the chance to sell a book to only one of the multiple students who eventually use it. Hence, publishers must cover their costs and make their profit in the first semester their books are sold-before used copies swamp the market. That's why the prices are so high. As might be expected, publishers do what they can to undermine the used-book market, principally by coming out with new editions every three or four years. To be sure, in rapidly changing fields like biol- ogy and physics, the new editions may be academically defensible. But in areas like algebra and calculus, they are nothing more than a trans- parent attempt to ensure premature textbook obsolescence. Publishers also try to discourage students from buying used books by bundling the text with extra materials like workbooks and CDs that are not reusable and therefore cannot be passed from one student to another. The system could be much improved if, first of all, colleges and publishers would acknowledge that textbooks are more akin to 248 GENRES 305 computer software than to trade books. A textbook's value, like that of a software program, is not in its physical form, but rather in its intellectual content. Therefore, just as software companies typically "site license" to colleges, so should textbook publishers. Here's how it would work: A teacher would pick a textbook, and the college would pay a negotiated fee to the publisher based on the number of students enrolled in the class. If there were 50 students in the class, for example, the fee might be $15 per student, or $750 for the semester. If the text were used for ten semesters, the publisher would ultimately receive a total of $150 ($15 X 10) for each student enrolled in the course, or as much as $7,500. In other words, the publisher would have a stream of revenue for 10 as long as the text was in use. Presumably, the university would pass on this fee to the students, just as it does the cost of laboratory supplies and computer software. But the students would pay much less than the $900 a semester they now typically pay for textbooks. Once the university had paid the license fee, each student would have the option of using the text in electronic format or paying more to purchase a hard copy through the usual channels. The publisher could set the price of hard copies low enough to cover only its pro- duction and distribution costs plus a small profit, because it would be covering most of its costs and making most of its profit by way of the license fees. The hard copies could then be resold to other students or back to the bookstore, but that would be of little concern to the publisher A further benefit of this approach is that it would not affect the way courses are taught. The same cannot be said for other rec- ommendations from the Congressional committee and from state legislatures, like placing teaching materials on electronic reserve, urging faculty to adopt cheaper "no frills" textbooks, and assigning mainly electronic textbooks. While each of these suggestions may have merit, they force faculty to weigh students' academic interests against their fiscal concerns and encourage them to rely less on new textbooks. Neither colleges nor publishers are known for their cutting-edge innovations. But if they could slightly change the way they do business, they would make a substantial dent in the cost of higher education and provide a real benefit to students and their parents. 20/Proposals A 249 This proposal clearly defines the problem-some textbooks cost a lot-and explains why. It proposes a solution to the problem of high textbook prices and offers reasons why this solution will work better than others. Its tone is reason- able and measured, yet decisive. Il For four more proposals, see CHAPTER 69 Key Features / Proposals A well-defined problem. Some problems are self-evident and relatively simple, and you would not need much persuasive power to make people act-as with the problem "This university discards too much paper."While some people might see nothing wrong with throwing paper away, most are likely to agree that recycling is a good thing. Other issues are controversial: some people see them as problems while others do not, such as this one: "Motorcycle riders who do not wear helmets risk serious injury and raise health-care costs for everyone." Some motorcyclists believe that wearing or not wearing a helmet should be a personal choice; you would have to present arguments to convince your readers that not wearing a helmet is indeed a problem needing a solution. Any written proposal must estab- lish at the outset that there is a problem-and that it's serious enough to require a solution. For some topics, visual or audio evidence of the problem may be helpful. 306 A recommended solution. Once you have defined the problem, you need to describe the solution you are suggesting and to explain it in enough detail for readers to understand what you are proposing. Again, photo- graphs, diagrams, or other visuals may help. Sometimes you might suggest several solutions, weigh their merits, and choose the best one. A convincing argument for your proposed solution. You need to con- vince readers that your solution is feasibleand that it is the best way to solve the problem. Sometimes you'll want to explain in detail how your proposed solution would work. See, for example, how the textbook proposal details the way a licensing system would operate. Visuals may strengthen this part of your argument as well. 250 GENRES LID PURCHASE AT STOMER SERVICE GOTTLE WIE MARGARIG QUALITY om MABLAGANG QUALITY USE 307 Granof's proposal for reducing textbook prices via licensing fees might benefit from a photograph like this one, which provides a comparison of other approaches to the problem, such as buying used books or renting them. A response to anticipated questions. You may need to consider any questions readers may have about your proposaland to show how its advantages outweigh any disadvantages. Had the textbook proposal been written for college budget officers, it would have needed to anticipate and answer questions about the costs of implementing the proposed solution. A call to action. The goal of a proposal is to persuade readers to accept your proposed solution. This solution may include asking readers to take action. An appropriate tone. Since you're trying to persuade readers to act, your tone is important-readers will always react better to a reasonable, respectful presentation than to anger or self-righteousness. 20/Proposals 251 A BRIEF GUIDE TO WRITING PROPOSALS Deciding on a Topic Choose a problem that can be solved. Complex, large problems, such as poverty, hunger, or terrorism, usually require complex, large solutions. Most of the time, focusing on a smaller problem or a limited aspect of a large problem will yield a more manageable proposal. Rather than tackling the problem of world poverty, for example, think about the problem faced by people in your community who have lost jobs and need help until they find employment Considering the Rhetorical Situation 55-56 308 57-60 PURPOSE Do you have a stake in a particular solution, or do you simply want to eliminate the problem by whatever solu- tion might be adopted? AUDIENCE Do your readers share your view of the problem as a serious one needing a solution? Are they likely to be open to possible solutions or resistant? Do they have the authority to carry out a proposed solution? STANCE How can you show your audience that your proposal is reasonable and should be taken seriously? How can you demonstrate your own authority and credibility? MEDIA / DESIGN How will you deliver your proposal? In print? Electroni- cally? As a speech? Would visuals, or video or audio clips help support your proposal? 66-68 69-71 Generating Ideas and Text Explore potential solutions to the problem. Many problems can be solved in more than one way, and you need to show your readers that you've examined several potential solutions. You may develop solutions 252 GENRES 477 424-31 on your own; more often, though, you'll need to do research to see how others have solved-or tried to solve-similar problems. Don't settle on a single solution too quickly, you'll need to COMPARE the advantages and disadvantages of several solutions in order to argue convincingly for one. Decide on the most desirable solution(s). One solution may be head and shoulders above others--but be open to rejecting all the possible solutions on your list and starting over if you need to, or to combining two or more potential solutions in order to come up with an acceptable fix. Think about why your solution is the best one. Why did you choose your solution? Why will it work better than others? What has to be done to enact it? What will it cost? What makes you think it can be done? Writing out answers to these questions will help you argue for your solution: to show that you have carefully and objectively outlined a problem, analyzed the potential solutions, weighed their merits, and determined the reasons the solution you propose is the best. Ways of Organizing a Proposal You can organize a proposal in various ways, but always you will begin by establishing that there is a problem. You may then identify several possible solutions before recommending one of them or a combination of several. Sometimes, however, you might discuss only a single solution. [Several possible solutions) Introduce and explain the problem Identify possible solutions, and consider their pros and cons one by one. Propose a solution, and give reasons why it is best Call for action, or reiterate your proposed action. 20/Proposals 253 [A single solution] Introduce and explain the problem. Explain the proposed solution Give reasons why it is the best solution. Call for action, or reiterate your proposal. Anticipate and answer questions. Taking Stock of Your Work Take stock of what you've written by writing out answers to these questions: How did you decide on and limit your topic? How did you go about researching your topic? How did you determine the best solution to the problem you defined? Did you use visual elements (tables, graphs, diagrams, photographs), audio elements, or links effectively? If not, would they have helped? What did you do well in this piece? What could still be improved? What would you do differently next time? What have you learned about the processes of writing from writing this piece? What do you need to work on in the future? TOPIC PROPOSALS 190-98 Instructors often ask students to write topic proposals to ensure that their topics are appropriate or manageable. Some instructors may also ask for an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY showing that appropriate sources of informa- tion are available--more evidence that the project can be carried out. Here a student proposes a topic for an assignment in a writing course in which she has been asked to take a position on a global issue. 20 Proposals Proposals are part of our personal lives: lovers propose marriage, friends propose sharing dinner and a movie, you offer to pay half the cost of a car and insurance if your parents will pay the other half. They are also part of our academic and professional lives: student leaders lobby for lights on bike paths. Musicians, artists, writers, and educators apply for grants. Researchers in all fields of the humanities, social sciences, sciences, and technology seek funding for their projects. In business, contractors bid on building projects, and companies and freelancers solicit work from potential clients. These are all examples of proposals, ideas put forward for consideration that say, "Here is a solution to a problem" or "This is what ought to be done." For example, here is a proposal for reducing the costs of college textbooks, written by an accounting professor at the University of Texas who is chairman of the university's Co-op Bookstore and himself a textbook author, 303 MICHAEL GRANOF Course Requirement: Extortion By now, entering college students and their parents have been warned: textbooks are outrageously expensive. Few textbooks for semester-long courses retail for less than $120, and those for science and math courses typically approach $180. Contrast this with the $20 to $30 cost of most hardcover best sellers and other trade books. Perhaps these students and their parents can take comfort in knowing that the federal government empathizes with them, and in an attempt to ease their pain Congress asked its Advisory Committee on Student Financial Assistance to suggest a cure for the problem. 246 20/Proposals 247 304 Unfortunately, though, the committee has proposed a remedy that would only worsen the problem. The committee's report, released in May, mainly proposes strength- ening the market for used textbooks-by encouraging college book- stores to guarantee that they will buy back textbooks, establishing online book swaps among students, and urging faculty to avoid switch- ing textbooks from one semester to the next. The fatal flaw in that proposal (and similar ones made by many state legislatures) is that used books are the cause of, not the cure for, high textbook prices. Yet there is a way to lighten the load for students in their budgets, if not their backpacks. With small modifications to the institutional arrangements between universities, publishers, and students, textbook costs could be reduced-and these changes could be made without government intervention. Today the used-book market is exceedingly well organized and 5 efficient. Campus bookstores buy back not only the books that will be used at their university the next semester but also those that will not Those that are no longer on their lists of required books they resell to national wholesalers, which in turn sell them to college bookstores on campuses where they will be required. This means that even if a text is being adopted for the first time at a particular college, there is almost certain to be an ample supply of used copies. As a result, publishers have the chance to sell a book to only one of the multiple students who eventually use it. Hence, publishers must cover their costs and make their profit in the first semester their books are sold-before used copies swamp the market. That's why the prices are so high. As might be expected, publishers do what they can to undermine the used-book market, principally by coming out with new editions every three or four years. To be sure, in rapidly changing fields like biol- ogy and physics, the new editions may be academically defensible. But in areas like algebra and calculus, they are nothing more than a trans- parent attempt to ensure premature textbook obsolescence. Publishers also try to discourage students from buying used books by bundling the text with extra materials like workbooks and CDs that are not reusable and therefore cannot be passed from one student to another. The system could be much improved if, first of all, colleges and publishers would acknowledge that textbooks are more akin to 248 GENRES 305 computer software than to trade books. A textbook's value, like that of a software program, is not in its physical form, but rather in its intellectual content. Therefore, just as software companies typically "site license" to colleges, so should textbook publishers. Here's how it would work: A teacher would pick a textbook, and the college would pay a negotiated fee to the publisher based on the number of students enrolled in the class. If there were 50 students in the class, for example, the fee might be $15 per student, or $750 for the semester. If the text were used for ten semesters, the publisher would ultimately receive a total of $150 ($15 X 10) for each student enrolled in the course, or as much as $7,500. In other words, the publisher would have a stream of revenue for 10 as long as the text was in use. Presumably, the university would pass on this fee to the students, just as it does the cost of laboratory supplies and computer software. But the students would pay much less than the $900 a semester they now typically pay for textbooks. Once the university had paid the license fee, each student would have the option of using the text in electronic format or paying more to purchase a hard copy through the usual channels. The publisher could set the price of hard copies low enough to cover only its pro- duction and distribution costs plus a small profit, because it would be covering most of its costs and making most of its profit by way of the license fees. The hard copies could then be resold to other students or back to the bookstore, but that would be of little concern to the publisher A further benefit of this approach is that it would not affect the way courses are taught. The same cannot be said for other rec- ommendations from the Congressional committee and from state legislatures, like placing teaching materials on electronic reserve, urging faculty to adopt cheaper "no frills" textbooks, and assigning mainly electronic textbooks. While each of these suggestions may have merit, they force faculty to weigh students' academic interests against their fiscal concerns and encourage them to rely less on new textbooks. Neither colleges nor publishers are known for their cutting-edge innovations. But if they could slightly change the way they do business, they would make a substantial dent in the cost of higher education and provide a real benefit to students and their parents. 20/Proposals A 249 This proposal clearly defines the problem-some textbooks cost a lot-and explains why. It proposes a solution to the problem of high textbook prices and offers reasons why this solution will work better than others. Its tone is reason- able and measured, yet decisive. Il For four more proposals, see CHAPTER 69 Key Features / Proposals A well-defined problem. Some problems are self-evident and relatively simple, and you would not need much persuasive power to make people act-as with the problem "This university discards too much paper."While some people might see nothing wrong with throwing paper away, most are likely to agree that recycling is a good thing. Other issues are controversial: some people see them as problems while others do not, such as this one: "Motorcycle riders who do not wear helmets risk serious injury and raise health-care costs for everyone." Some motorcyclists believe that wearing or not wearing a helmet should be a personal choice; you would have to present arguments to convince your readers that not wearing a helmet is indeed a problem needing a solution. Any written proposal must estab- lish at the outset that there is a problem-and that it's serious enough to require a solution. For some topics, visual or audio evidence of the problem may be helpful. 306 A recommended solution. Once you have defined the problem, you need to describe the solution you are suggesting and to explain it in enough detail for readers to understand what you are proposing. Again, photo- graphs, diagrams, or other visuals may help. Sometimes you might suggest several solutions, weigh their merits, and choose the best one. A convincing argument for your proposed solution. You need to con- vince readers that your solution is feasibleand that it is the best way to solve the problem. Sometimes you'll want to explain in detail how your proposed solution would work. See, for example, how the textbook proposal details the way a licensing system would operate. Visuals may strengthen this part of your argument as well. 250 GENRES LID PURCHASE AT STOMER SERVICE GOTTLE WIE MARGARIG QUALITY om MABLAGANG QUALITY USE 307 Granof's proposal for reducing textbook prices via licensing fees might benefit from a photograph like this one, which provides a comparison of other approaches to the problem, such as buying used books or renting them. A response to anticipated questions. You may need to consider any questions readers may have about your proposaland to show how its advantages outweigh any disadvantages. Had the textbook proposal been written for college budget officers, it would have needed to anticipate and answer questions about the costs of implementing the proposed solution. A call to action. The goal of a proposal is to persuade readers to accept your proposed solution. This solution may include asking readers to take action. An appropriate tone. Since you're trying to persuade readers to act, your tone is important-readers will always react better to a reasonable, respectful presentation than to anger or self-righteousness. 20/Proposals 251 A BRIEF GUIDE TO WRITING PROPOSALS Deciding on a Topic Choose a problem that can be solved. Complex, large problems, such as poverty, hunger, or terrorism, usually require complex, large solutions. Most of the time, focusing on a smaller problem or a limited aspect of a large problem will yield a more manageable proposal. Rather than tackling the problem of world poverty, for example, think about the problem faced by people in your community who have lost jobs and need help until they find employment Considering the Rhetorical Situation 55-56 308 57-60 PURPOSE Do you have a stake in a particular solution, or do you simply want to eliminate the problem by whatever solu- tion might be adopted? AUDIENCE Do your readers share your view of the problem as a serious one needing a solution? Are they likely to be open to possible solutions or resistant? Do they have the authority to carry out a proposed solution? STANCE How can you show your audience that your proposal is reasonable and should be taken seriously? How can you demonstrate your own authority and credibility? MEDIA / DESIGN How will you deliver your proposal? In print? Electroni- cally? As a speech? Would visuals, or video or audio clips help support your proposal? 66-68 69-71 Generating Ideas and Text Explore potential solutions to the problem. Many problems can be solved in more than one way, and you need to show your readers that you've examined several potential solutions. You may develop solutions 252 GENRES 477 424-31 on your own; more often, though, you'll need to do research to see how others have solved-or tried to solve-similar problems. Don't settle on a single solution too quickly, you'll need to COMPARE the advantages and disadvantages of several solutions in order to argue convincingly for one. Decide on the most desirable solution(s). One solution may be head and shoulders above others--but be open to rejecting all the possible solutions on your list and starting over if you need to, or to combining two or more potential solutions in order to come up with an acceptable fix. Think about why your solution is the best one. Why did you choose your solution? Why will it work better than others? What has to be done to enact it? What will it cost? What makes you think it can be done? Writing out answers to these questions will help you argue for your solution: to show that you have carefully and objectively outlined a problem, analyzed the potential solutions, weighed their merits, and determined the reasons the solution you propose is the best. Ways of Organizing a Proposal You can organize a proposal in various ways, but always you will begin by establishing that there is a problem. You may then identify several possible solutions before recommending one of them or a combination of several. Sometimes, however, you might discuss only a single solution. [Several possible solutions) Introduce and explain the problem Identify possible solutions, and consider their pros and cons one by one. Propose a solution, and give reasons why it is best Call for action, or reiterate your proposed action. 20/Proposals 253 [A single solution] Introduce and explain the problem. Explain the proposed solution Give reasons why it is the best solution. Call for action, or reiterate your proposal. Anticipate and answer questions. Taking Stock of Your Work Take stock of what you've written by writing out answers to these questions: How did you decide on and limit your topic? How did you go about researching your topic? How did you determine the best solution to the problem you defined? Did you use visual elements (tables, graphs, diagrams, photographs), audio elements, or links effectively? If not, would they have helped? What did you do well in this piece? What could still be improved? What would you do differently next time? What have you learned about the processes of writing from writing this piece? What do you need to work on in the future? TOPIC PROPOSALS 190-98 Instructors often ask students to write topic proposals to ensure that their topics are appropriate or manageable. Some instructors may also ask for an ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY showing that appropriate sources of informa- tion are available--more evidence that the project can be carried out. Here a student proposes a topic for an assignment in a writing course in which she has been asked to take a position on a global issue