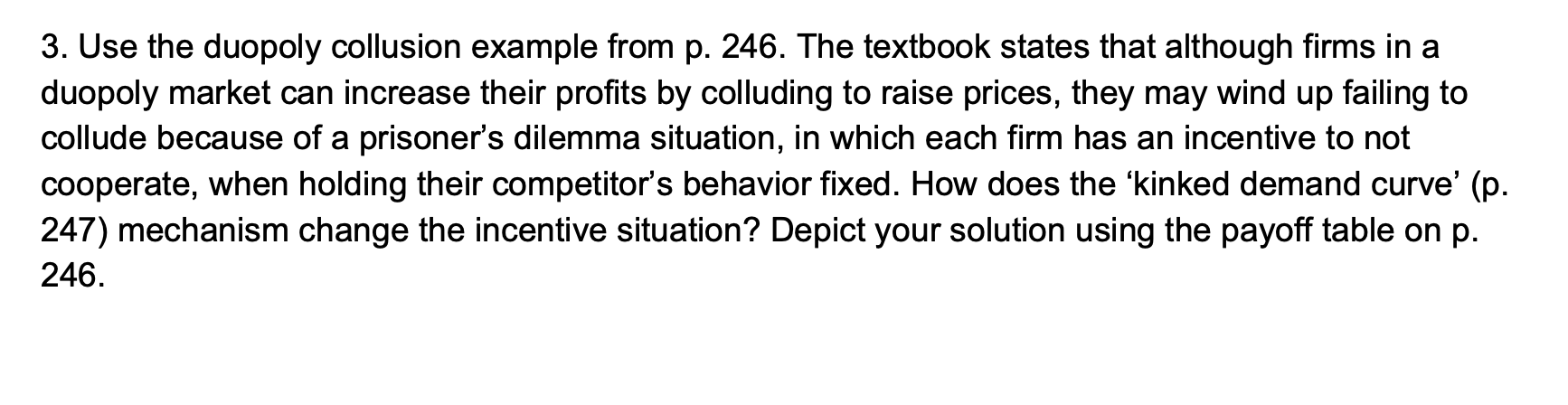

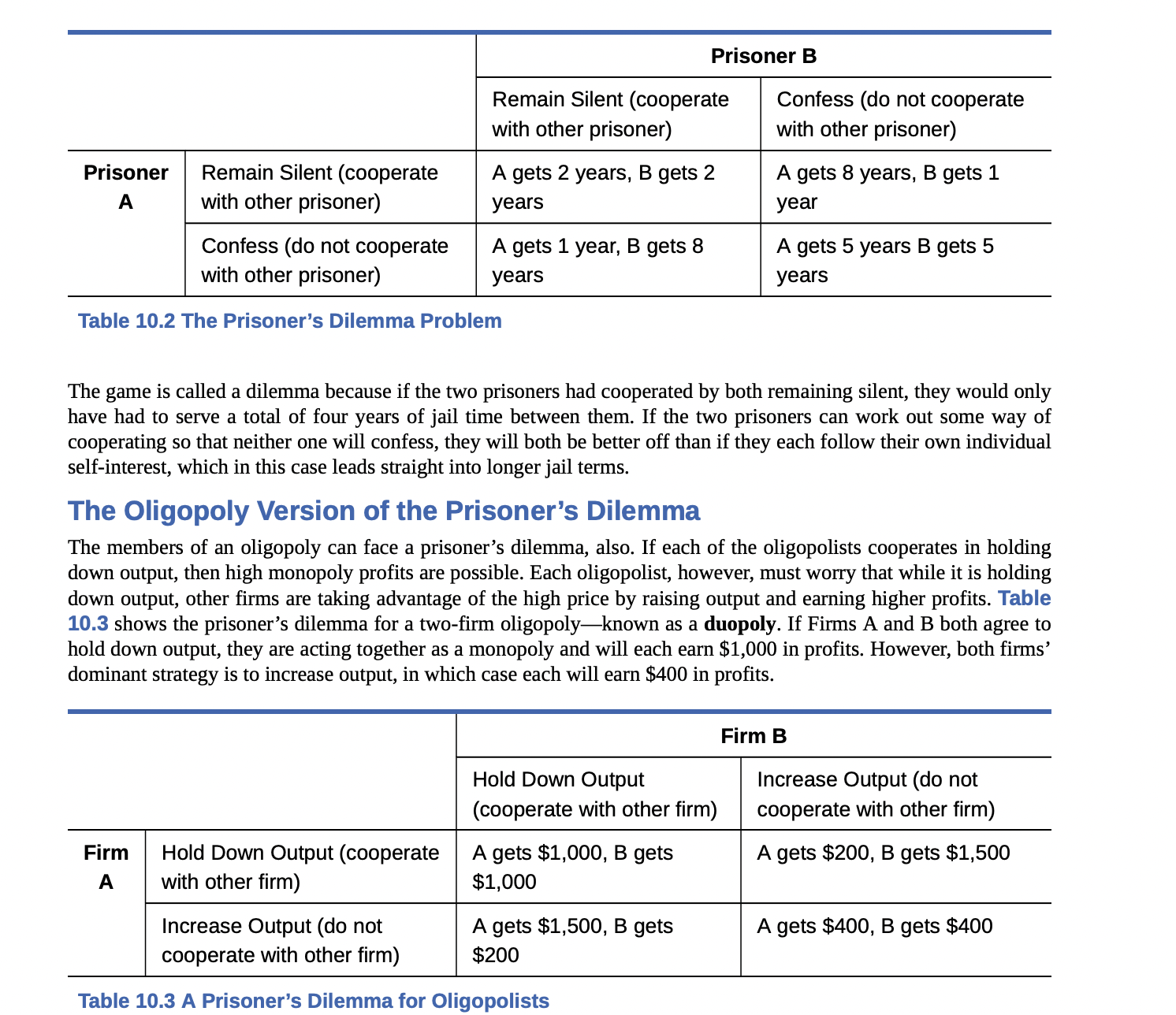

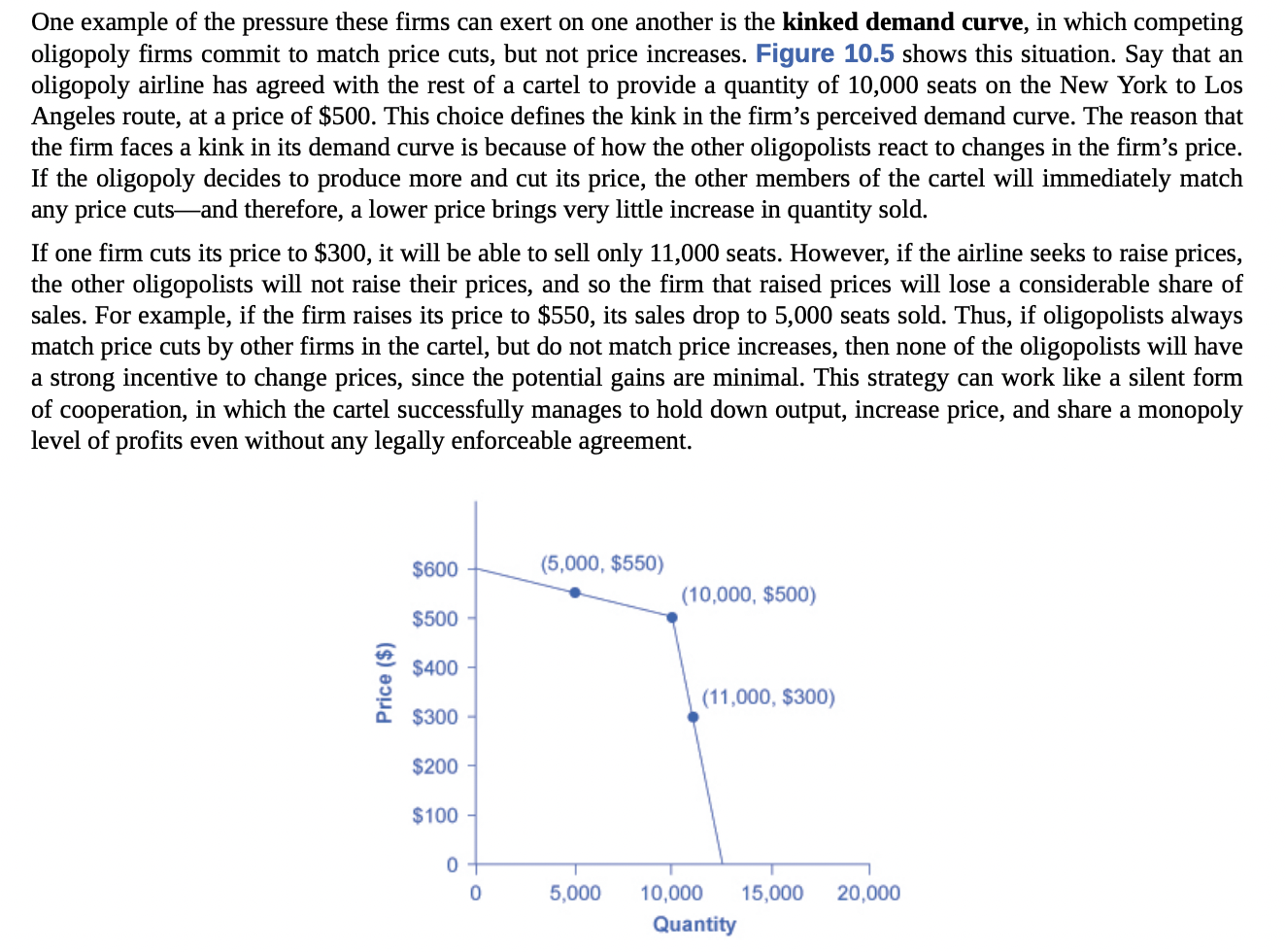

3. Use the duopoly collusion example from p. 246. The textbook states that although firms in a duopoly market can increase their prots by colluding to raise prices, they may wind up failing to collude because of a prisoner's dilemma situation, in which each firm has an incentive to not cooperate, when holding their competitor's behavior fixed. How does the 'kinked demand curve' (p. 247) mechanism change the incentive situation? Depict your solution using the payoff table on p. 246. Prisoner B Remain Silent (cooperate with other prisoner) Confess (do not cooperate with other prisoner) Prisoner Remain Silent (cooperate A gets 2 years, B gets 2 A gets 8 years, B gets 1 A with other prisoner) years year A gets 5 years B gets 5 years Confess (do not cooperate A gets 1 year, B gets 8 with other prisoner) years Table 10.2 The Prisoner's Dilemma Problem The game is called a dilemma because if the two prisoners had cooperated by both remaining silent, they would only have had to serve a total of four years of jail time between them. If the two prisoners can work out some way of cooperating so that neither one will confess, they will both be better off than if they each follow their own individual self-interest, which in this case leads straight into longer jail terms. The Oligopoly Version of the Prisoner's Dilemma The members of an oligopoly can face a prisoner's dilemma, also. If each of the oligopolists cooperates in holding down output, then high monopoly prots are possible. Each oligopolist, however, must worry that while it is holding down output, other rms are taking advantage of the high price by raising output and earning higher profits. Table 10.3 shows the prisoner's dilemma for a two-rm Oligopolyknown as a duopoly. If Firms A and B both agree to hold down output, they are acting together as a monopoly and will each earn $1,000 in profits. However, both firms' dominant strategy is to increase output, in which case each will earn $400 in prots. Increase Output (do not cooperate with other firm) Hold Down Output (cooperate with other firm) Hold Down Output (cooperate A gets $1,000, B gets with other firm) $1,000 Increase Output (do not A gets $1,500, B gets cooperate with other firm) $200 Table 10.3 A Prisoner's Dilemma for Oligopolists A gets $200, B gets $1,500 A gets $400, B gets $400 One example of the pressure these firms can exert on one another is the kinked demand curve, in which competing oligopoly firms commit to match price cuts, but not price increases. Figure 10.5 shows this situation. Say that an oligopoly airline has agreed with the rest of a cartel to provide a quantity of 10,000 seats on the New York to Los Angeles route, at a price of $500. This choice denes the kink in the firm's perceived demand curve. The reason that the firm faces a kink in its demand curve is because of how the other oligopolists react to changes in the firm's price. If the oligopoly decides to produce more and cut its price, the other members of the cartel will immediately match any price cutsand therefore, a lower price brings very little increase in quantity sold. If one firm cuts its price to $300, it will be able to sell only 11,000 seats. However, if the airline seeks to raise prices, the other oligopolists will not raise their prices, and so the firm that raised prices will lose a considerable share of sales. For example, if the firm raises its price to $550, its sales drop to 5,000 seats sold. Thus, if oligopolists always match price cuts by other firms in the cartel, but do not match price increases, then none of the oligopolists will have a strong incentive to change prices, since the potential gains are minimal. This strategy can work like a silent form of cooperation, in which the cartel successfully manages to hold down output, increase price, and share a monopoly level of profits even without any legally enforceable agreement. (5,000, $550) (10,000, $500) (11,000. 3300) 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 20,000 Quantity